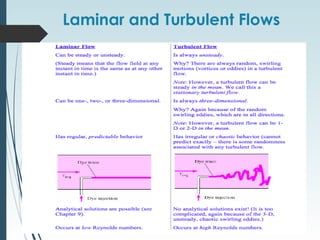

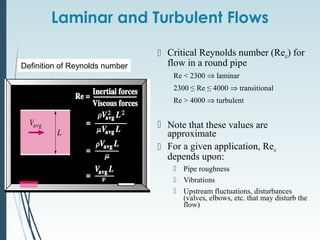

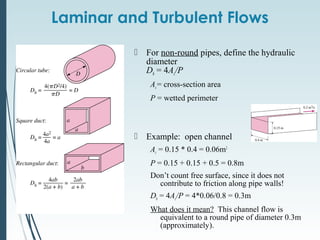

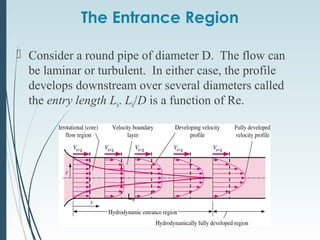

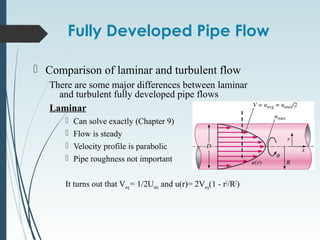

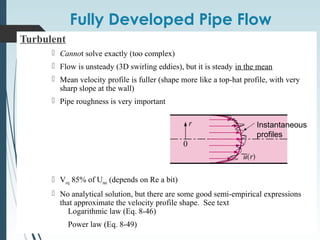

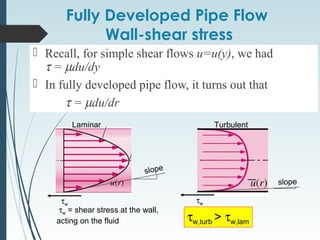

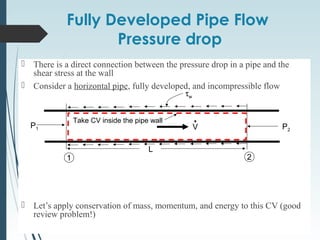

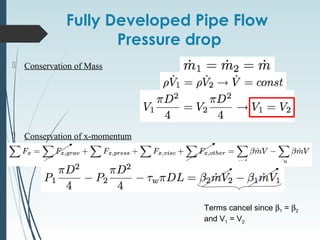

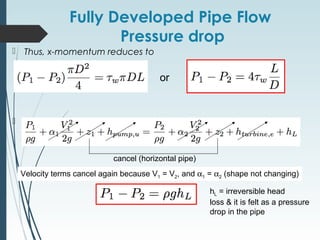

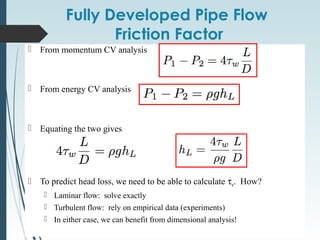

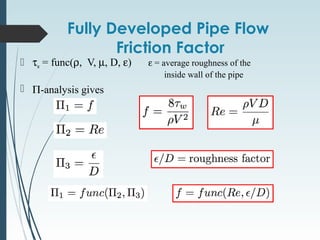

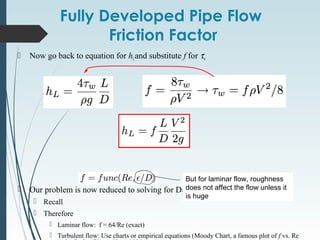

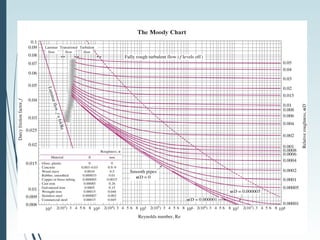

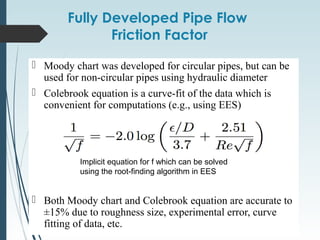

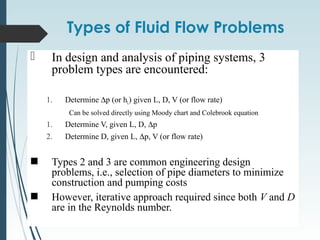

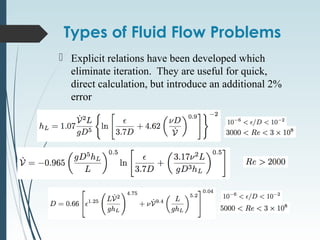

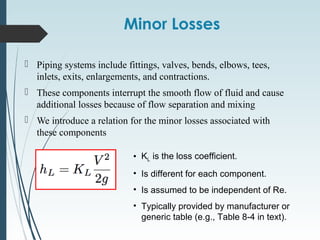

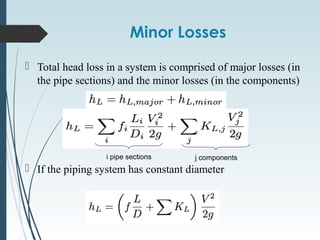

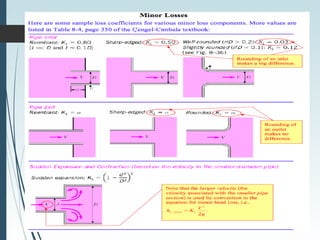

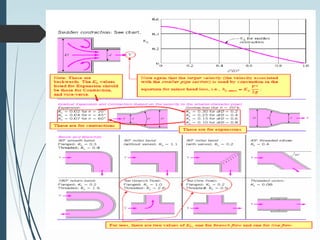

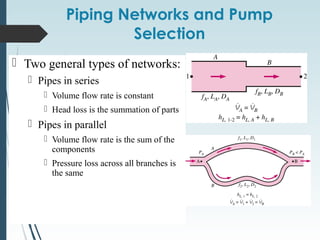

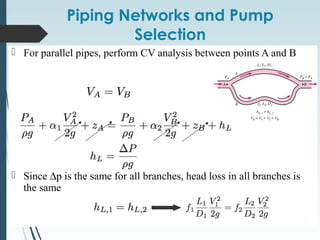

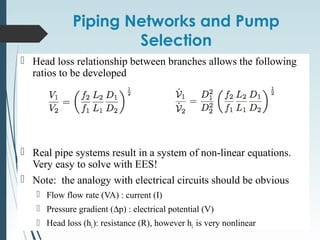

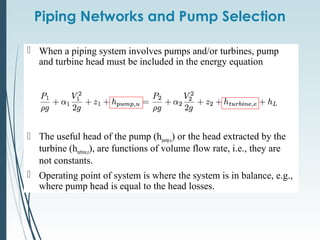

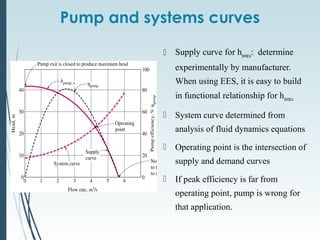

This document discusses laminar and turbulent flow in pipes. It defines the critical Reynolds number that distinguishes between the two flow regimes. For non-circular pipes, it introduces the hydraulic diameter to characterize the pipe geometry. The document then covers topics such as the developing flow region, fully developed flow profiles and pressure drop, the friction factor, minor losses, pipe networks, and pump selection.