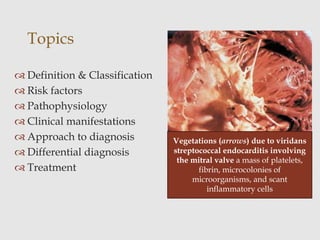

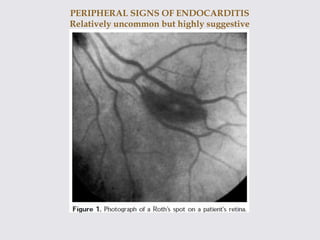

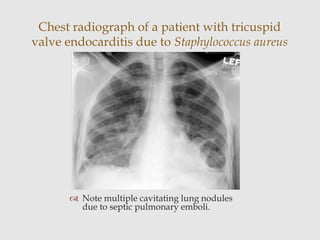

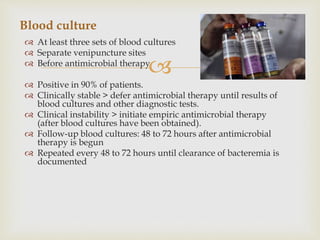

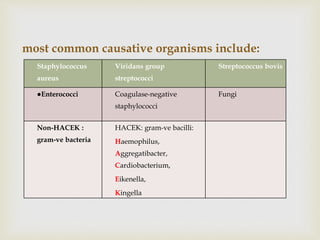

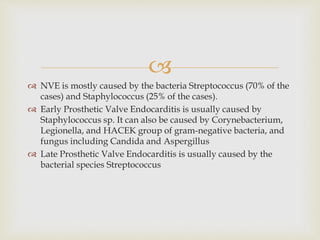

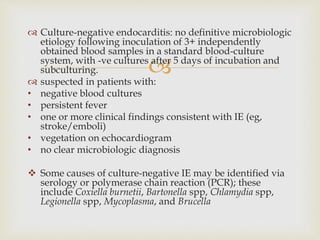

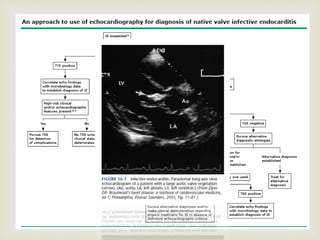

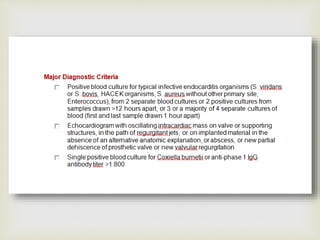

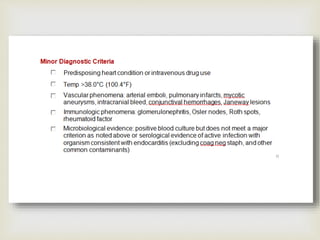

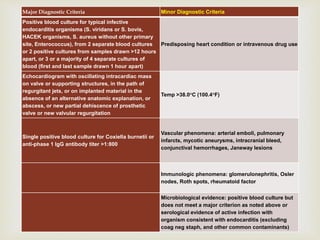

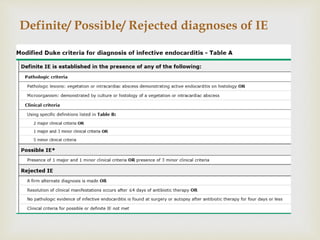

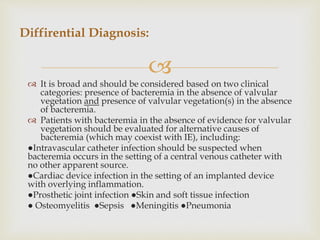

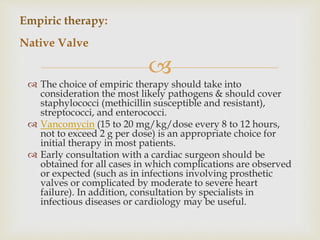

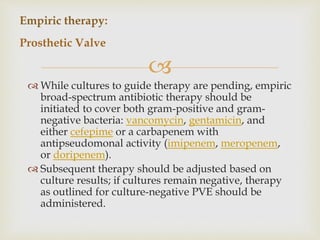

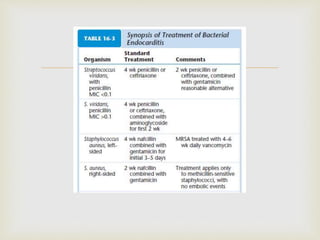

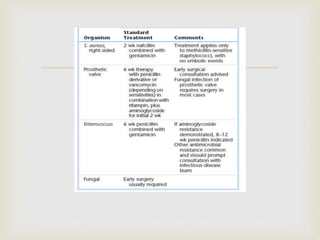

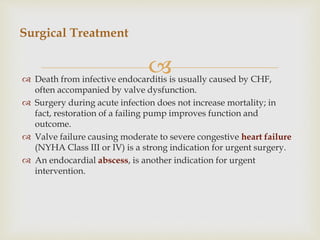

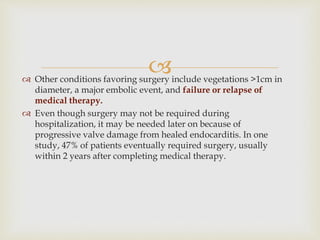

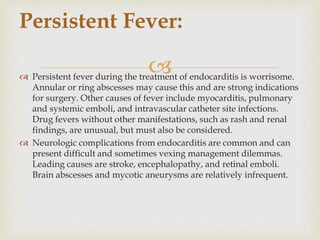

The document provides a comprehensive overview of infective endocarditis (IE), including its definition, classification, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. It highlights the importance of early diagnosis and empiric therapy while outlining the role of echocardiography and blood cultures in diagnosis. Key risk factors include previous IE, age, and certain medical conditions, and the document discusses the need for surgical intervention in severe cases.