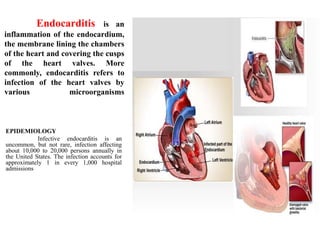

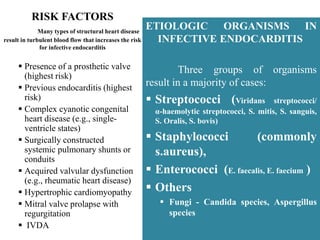

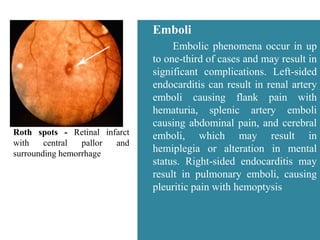

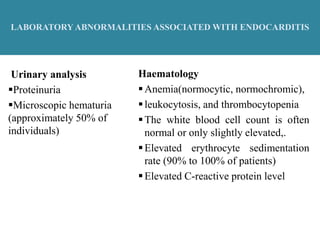

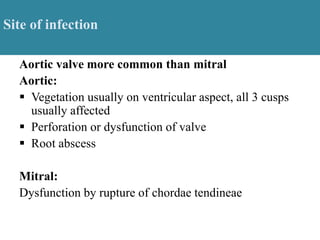

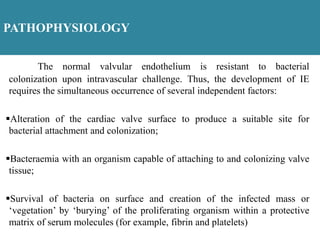

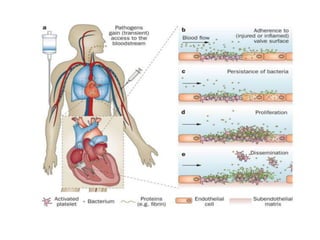

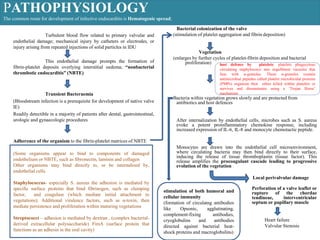

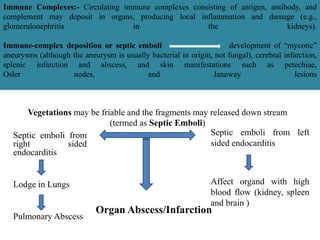

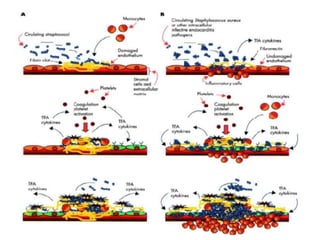

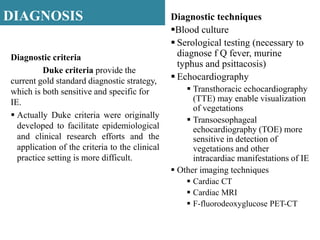

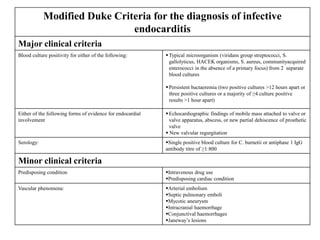

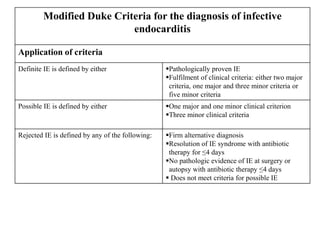

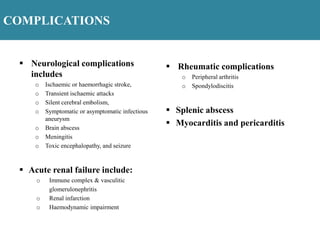

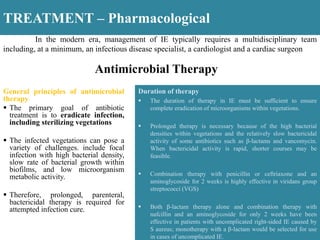

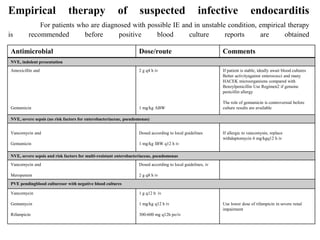

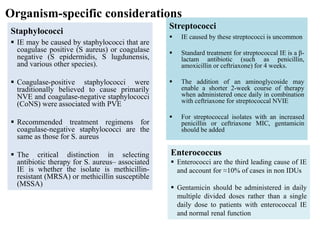

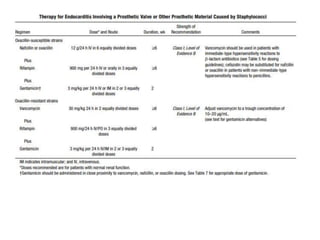

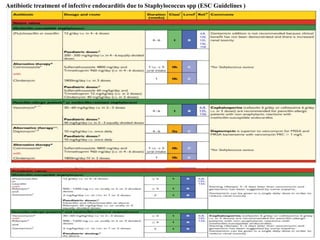

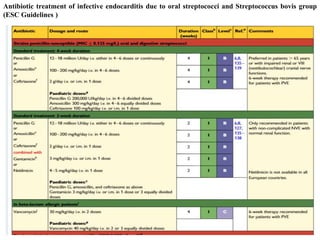

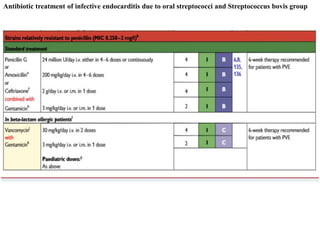

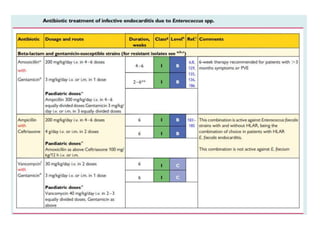

Endocarditis is an inflammation of the heart's inner lining, typically due to infection from microorganisms, affecting 10,000 to 20,000 individuals annually in the U.S. It presents mainly as acute or subacute cases, with symptoms including fever, heart murmurs, and various embolic phenomena; diagnosis involves criteria and techniques such as blood cultures and echocardiography. Treatment includes prolonged antibiotic therapy and may require surgical intervention for severe cases or complications.