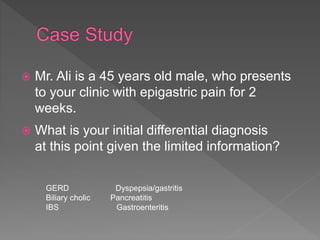

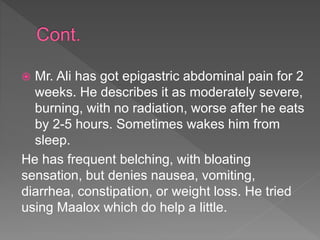

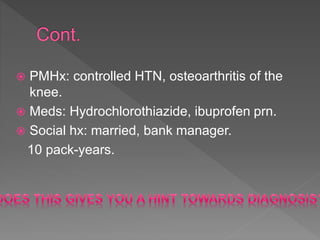

Mr. Ali, a 45-year-old male, presents with epigastric pain for two weeks, which is moderately severe and worsens after meals; he has a history of controlled hypertension and osteoarthritis. Differential diagnoses include GERD, dyspepsia, gastritis, and potential peptic ulcer disease, particularly given his NSAID use and symptoms. The management strategy includes H. pylori testing, antisecretory therapy, and potential surgical intervention for complications as needed.

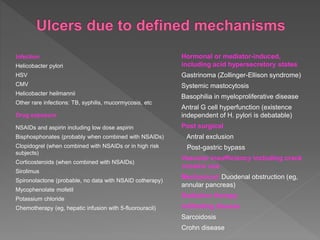

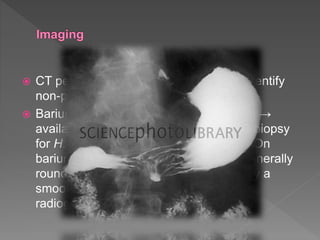

![ Other causes of peptic ulcer disease should be considered

when H. pylori and use of NSAIDs have been excluded

(eg, gastrinoma in patients with multiple simultaneous

ulcers, or those in unusual locations [second portion of the

duodenum & into the proximal jejunum]).

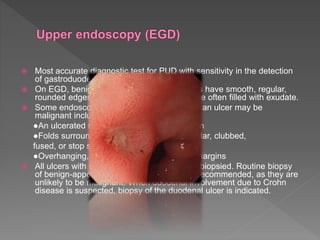

In patients with gastric ulcers without a clear etiology, we

perform an EGD12 weeks after initiating medical therapy

(with biopsies if refractory). This allows to exclude

neoplastic, infiltrative, or infectious causes of ulceration.

This decision may need to be individualized based on the

prevalence of gastric cancer in the community and

individual risk factors for the patient.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pepticulclerdisease-181109085632/85/Peptic-ulcler-disease-17-320.jpg)