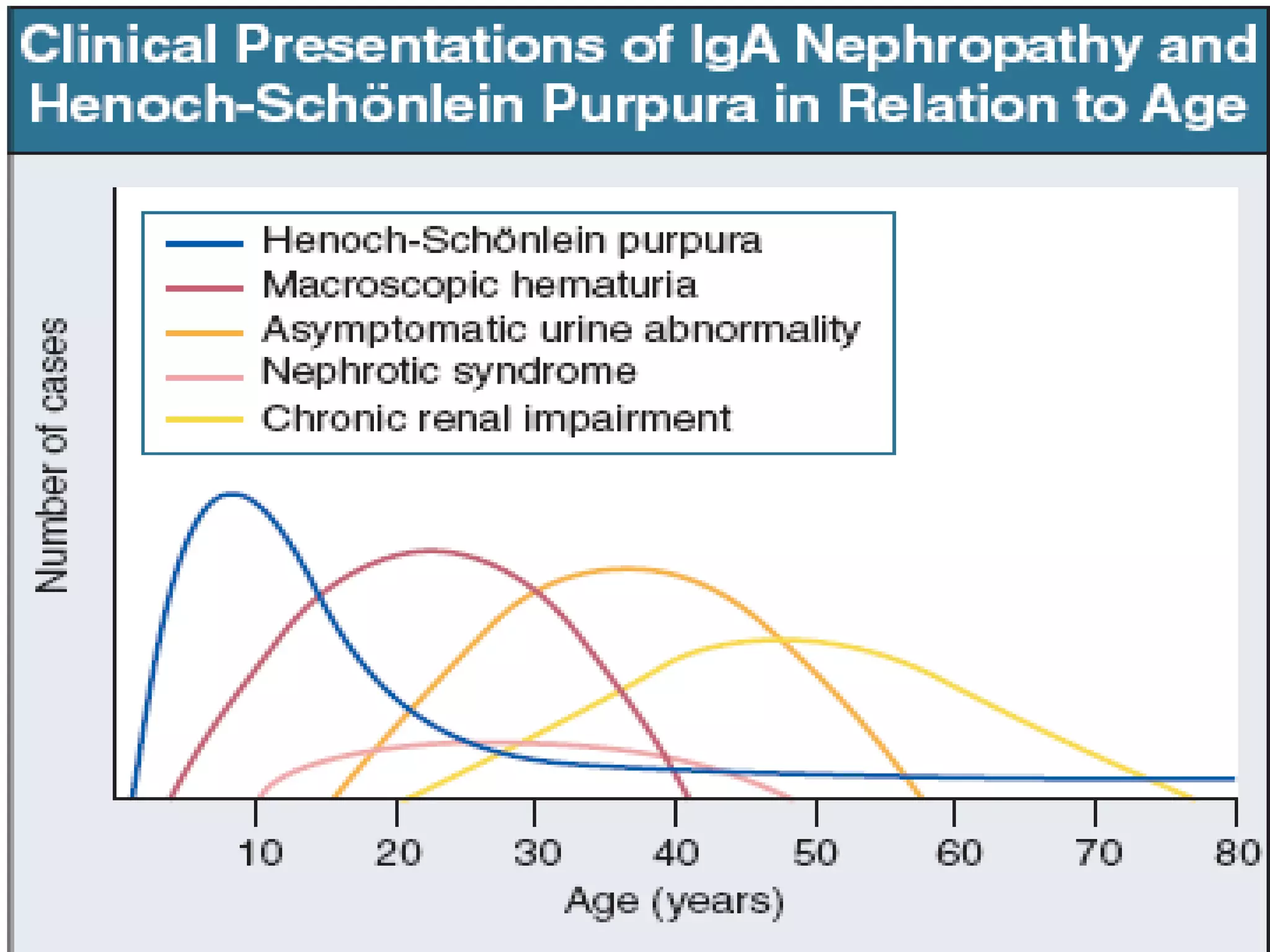

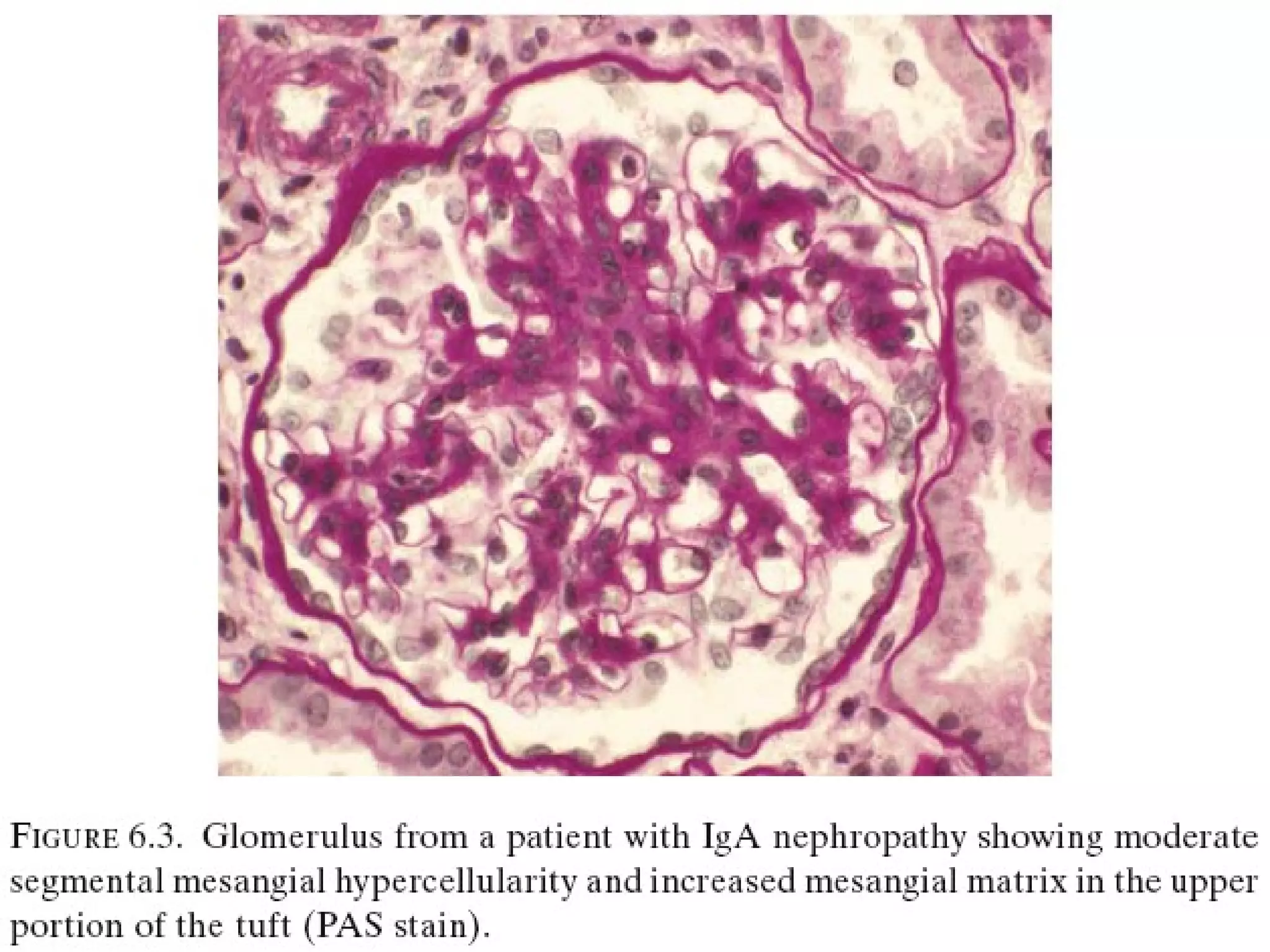

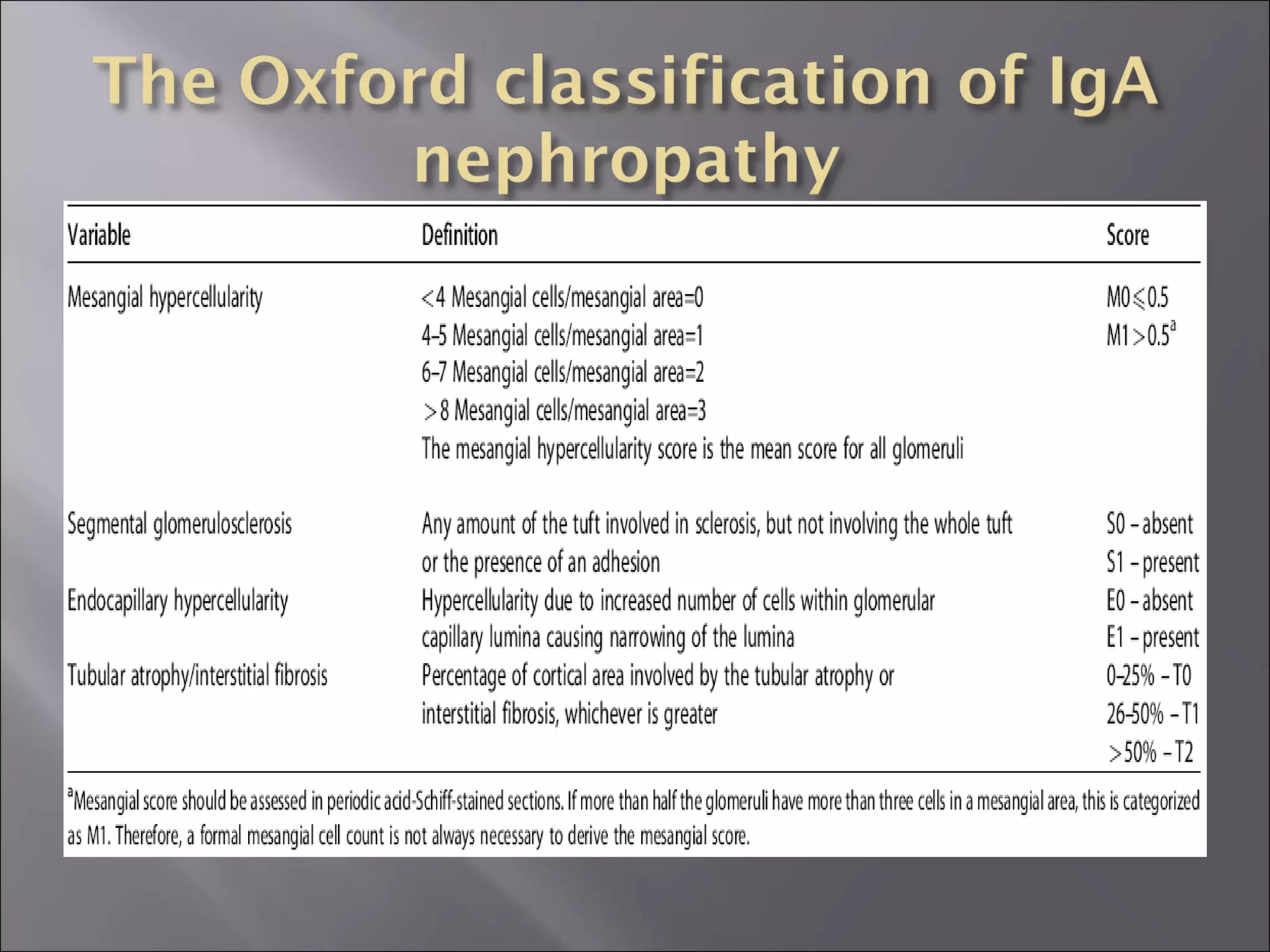

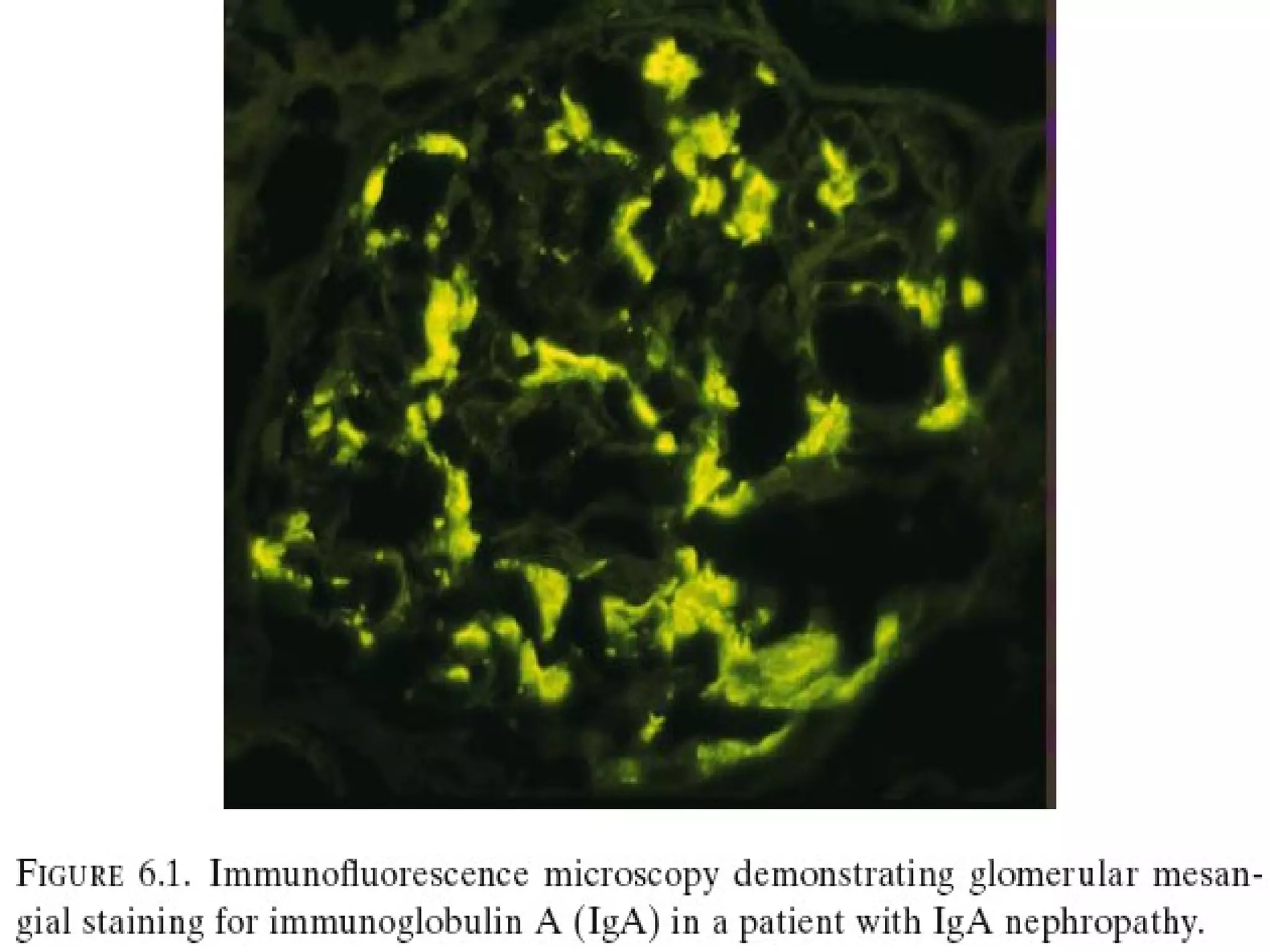

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy, also known as Berger's disease, is characterized by IgA-dominant mesangial deposits and can present with varying clinical symptoms such as hematuria, nephrotic syndrome, and chronic renal failure. Diagnosis typically requires kidney biopsy, while treatment approaches may include blood pressure management, glucocorticoids, and immunosuppressive therapy depending on disease severity. Prognosis is influenced by clinical factors including hypertension and renal dysfunction at diagnosis, with ongoing research needed to optimize treatment strategies.