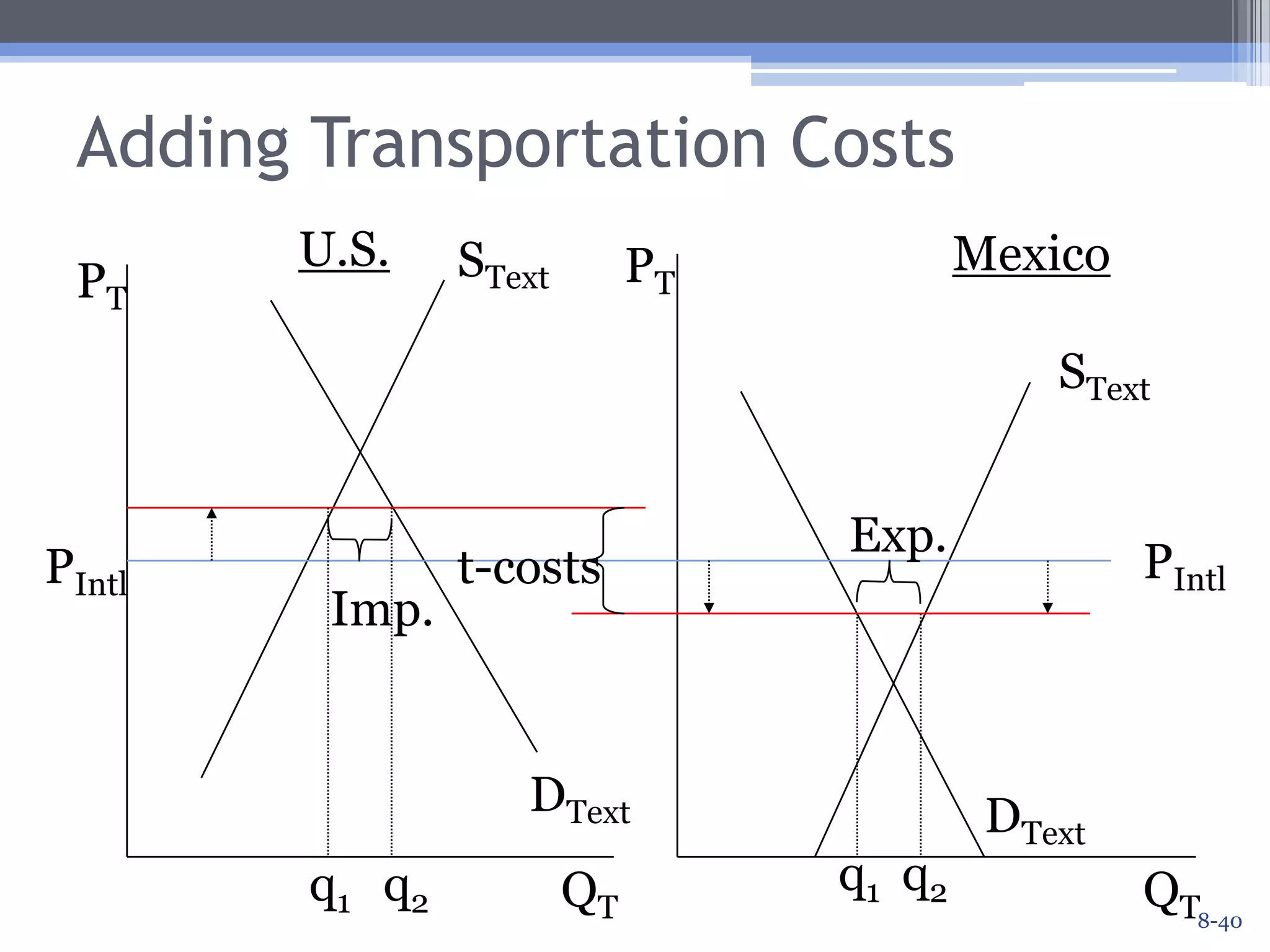

This document provides a summary of the Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade. It discusses the model's key assumptions, concepts, and implications. The summary is as follows:

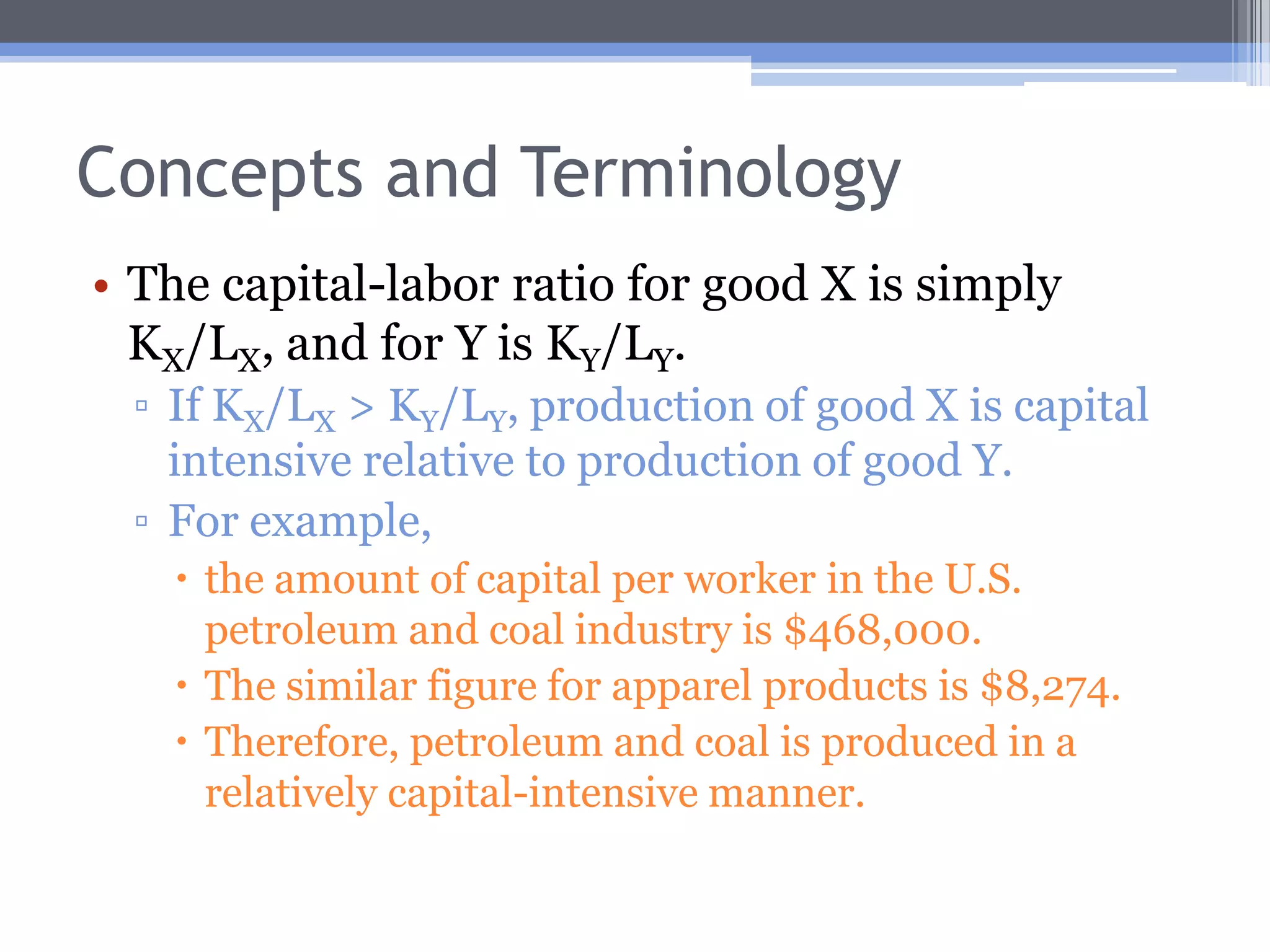

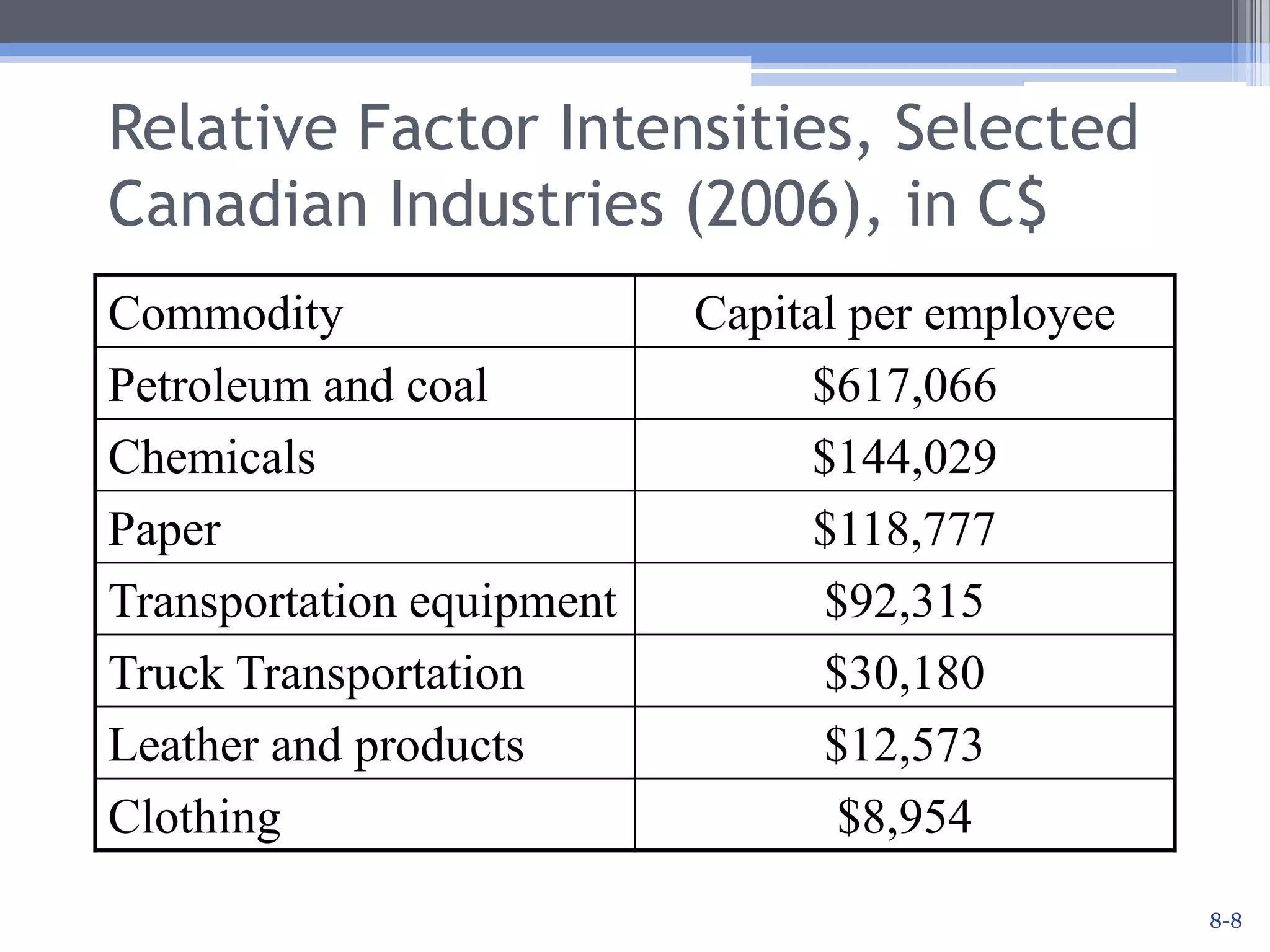

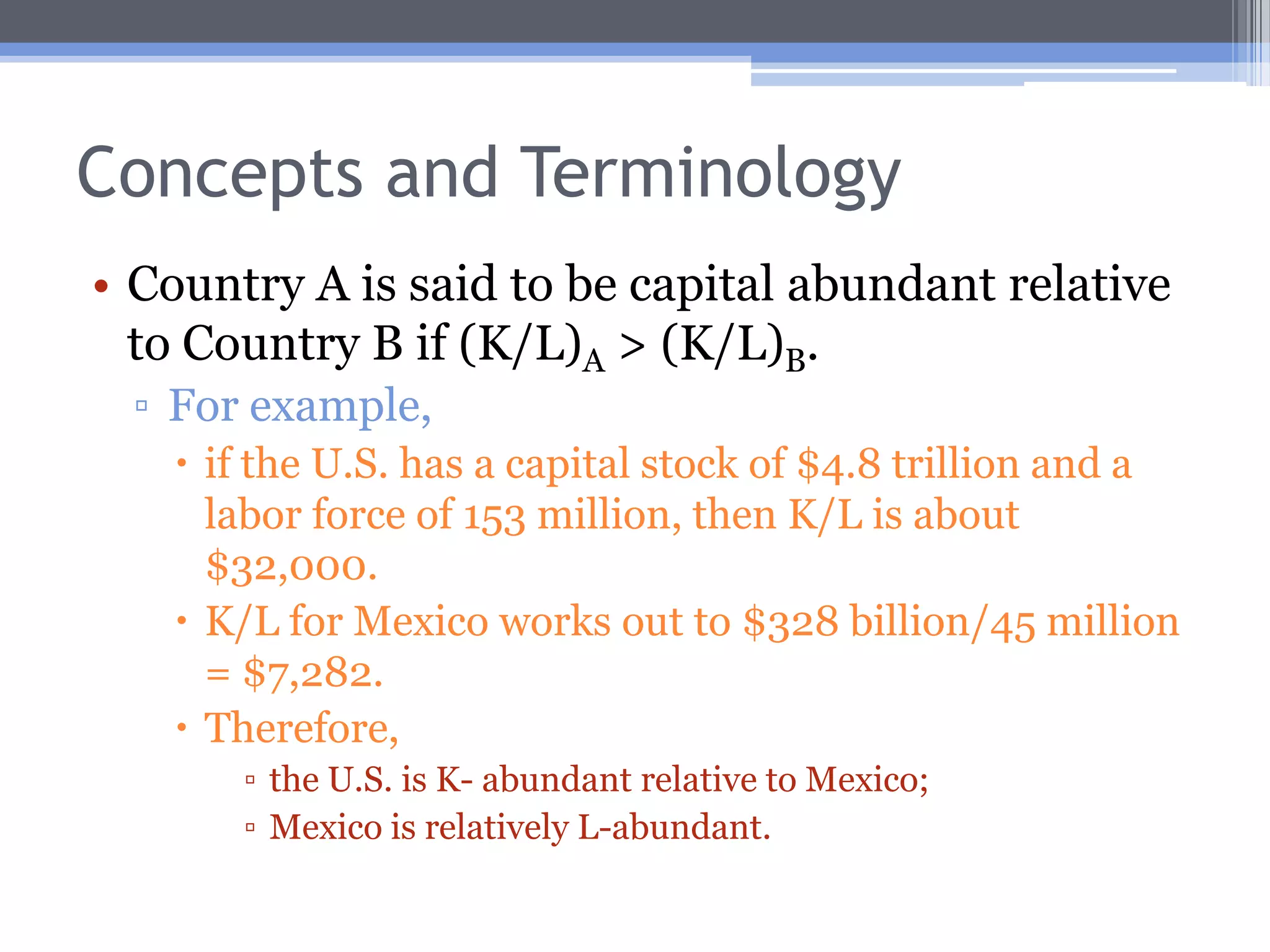

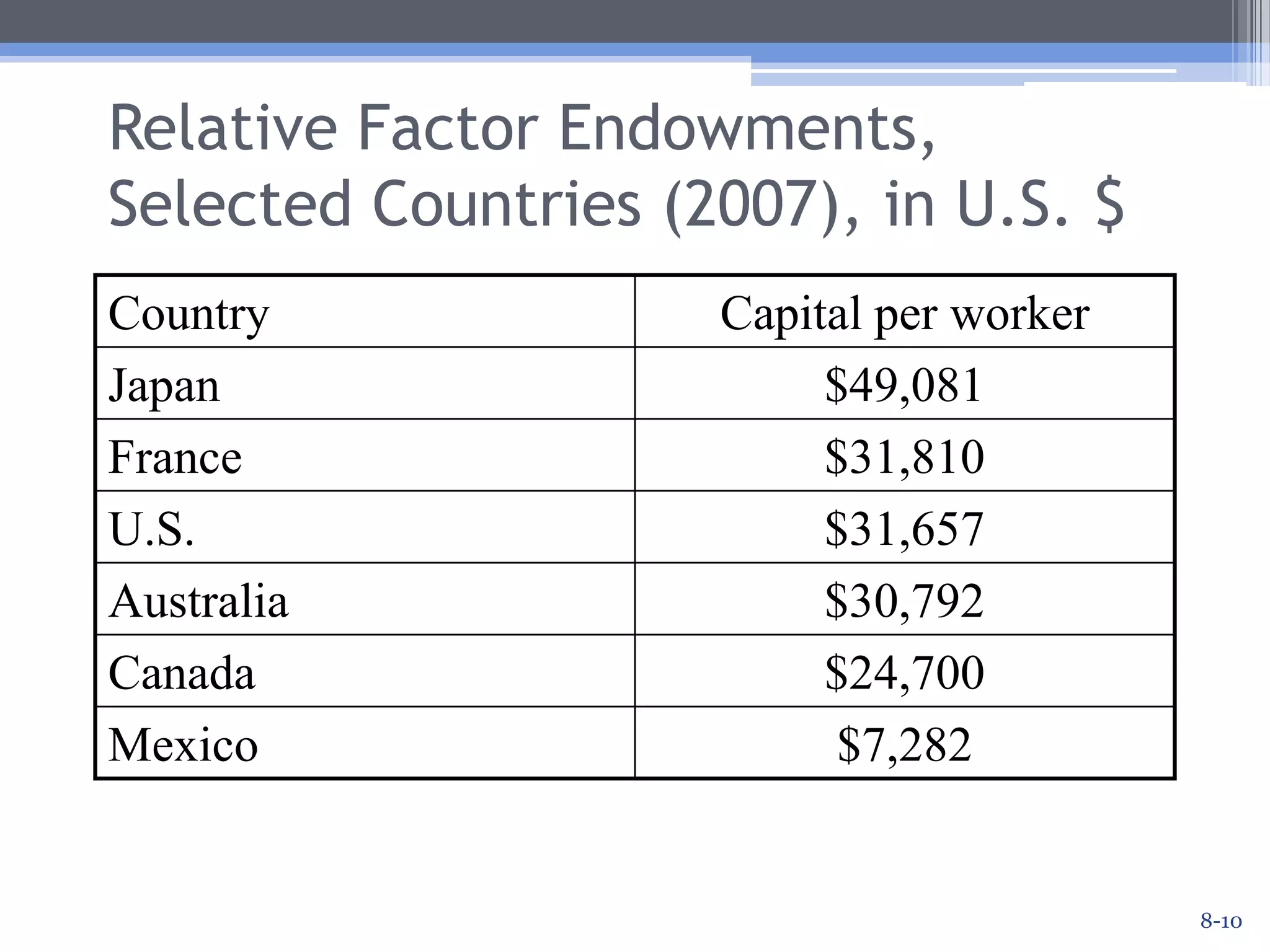

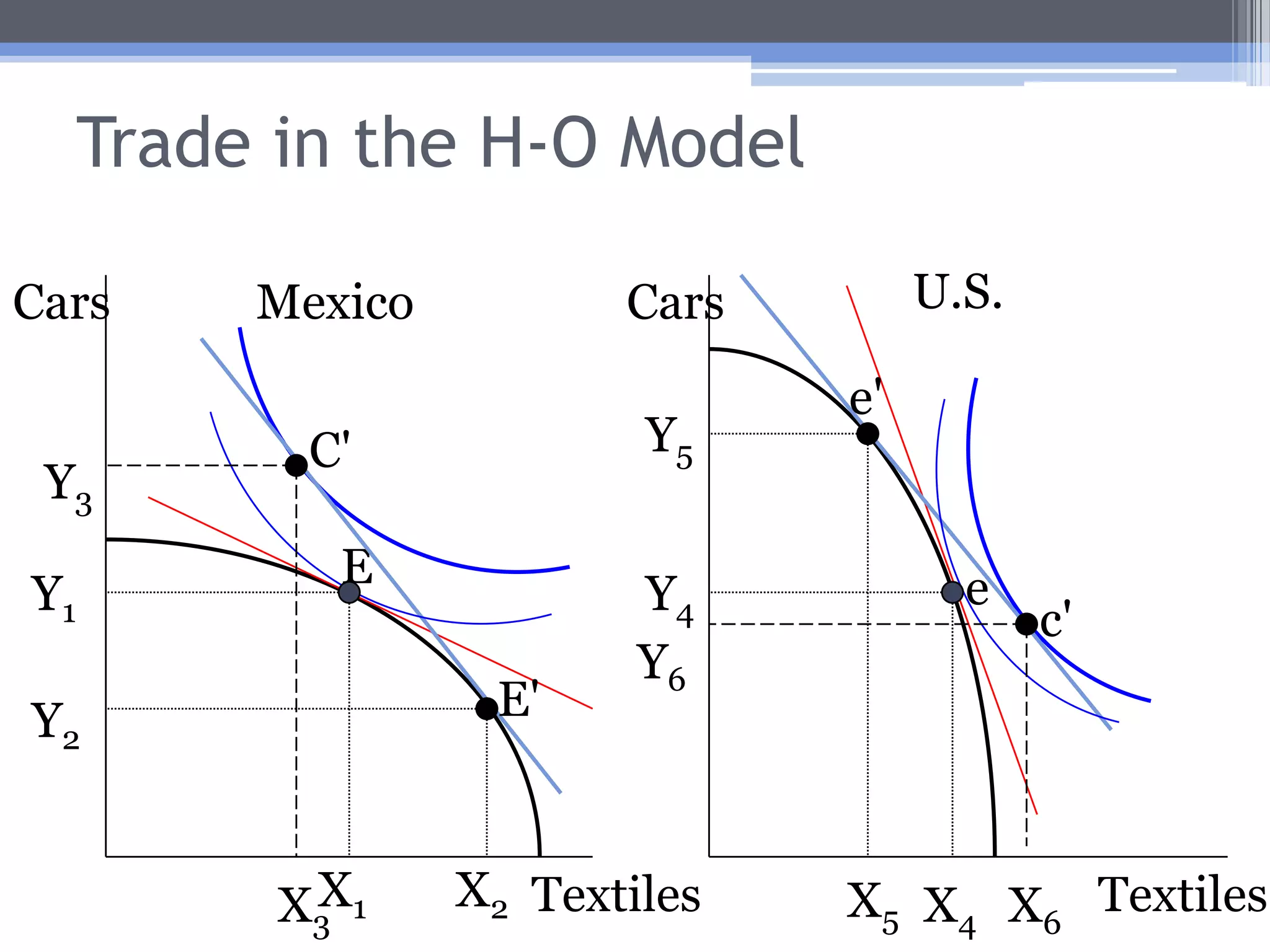

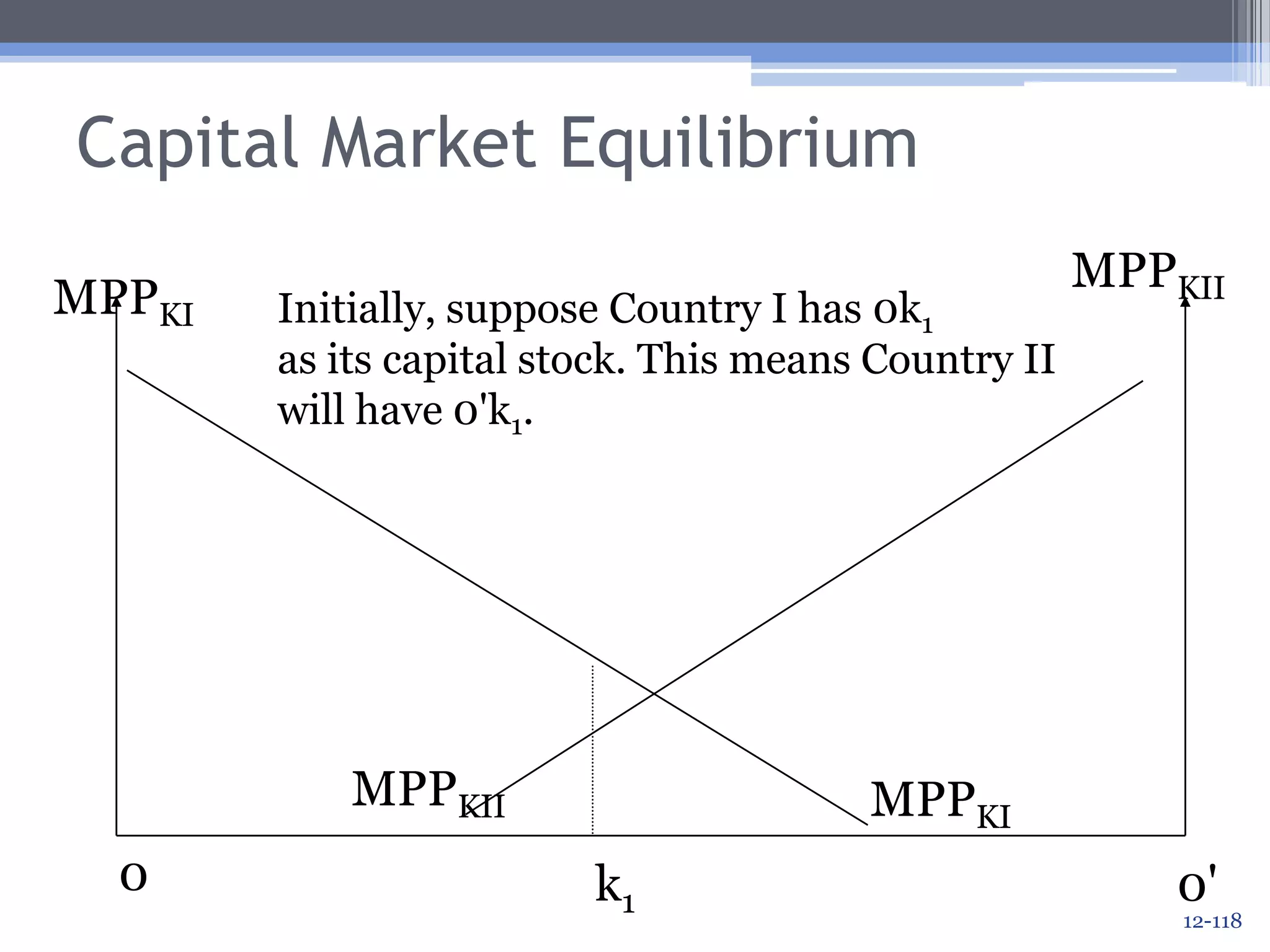

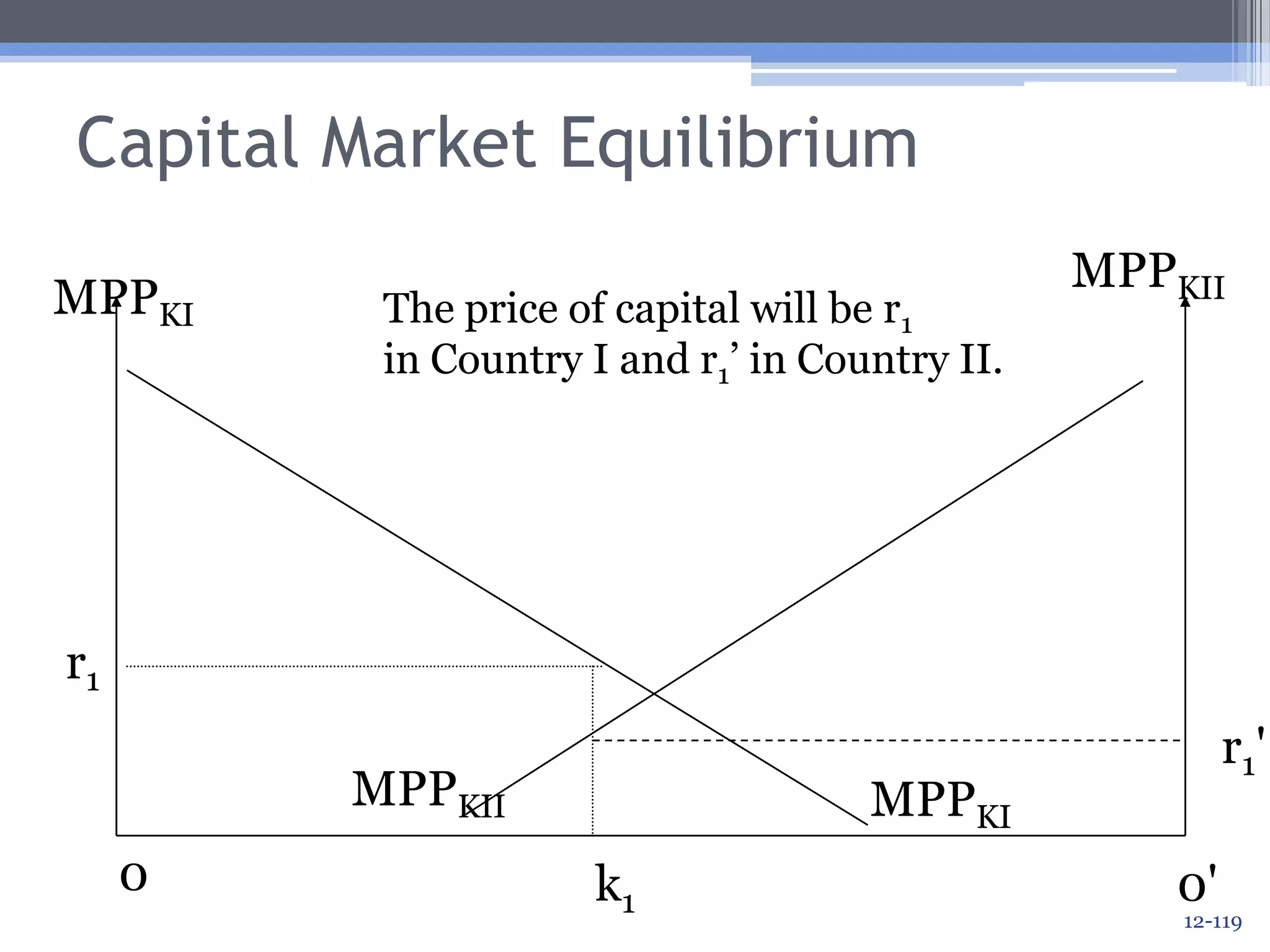

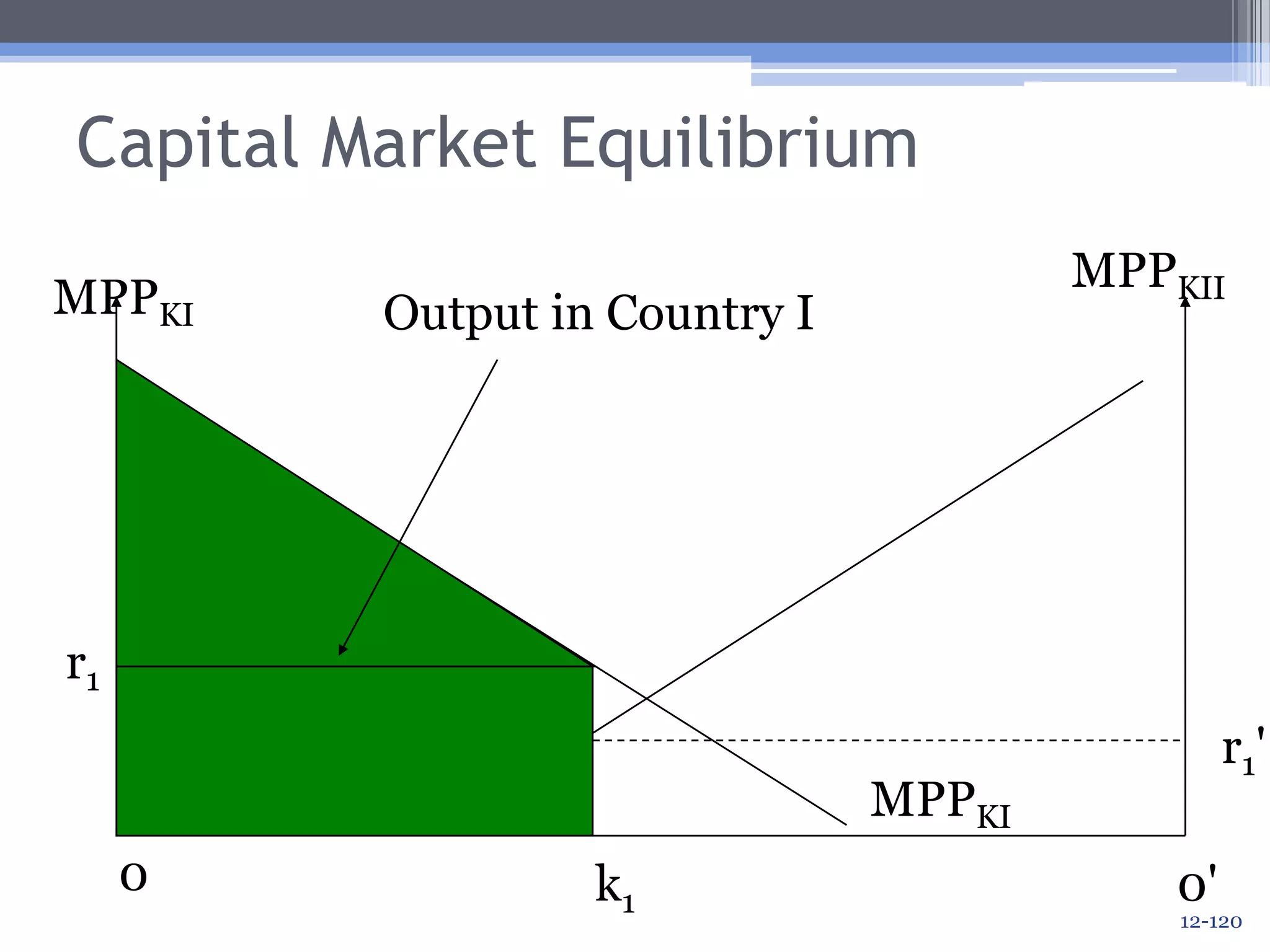

1) The Heckscher-Ohlin model examines how differences in countries' factor endowments (e.g. capital vs. labor) lead to comparative advantages and patterns of trade.

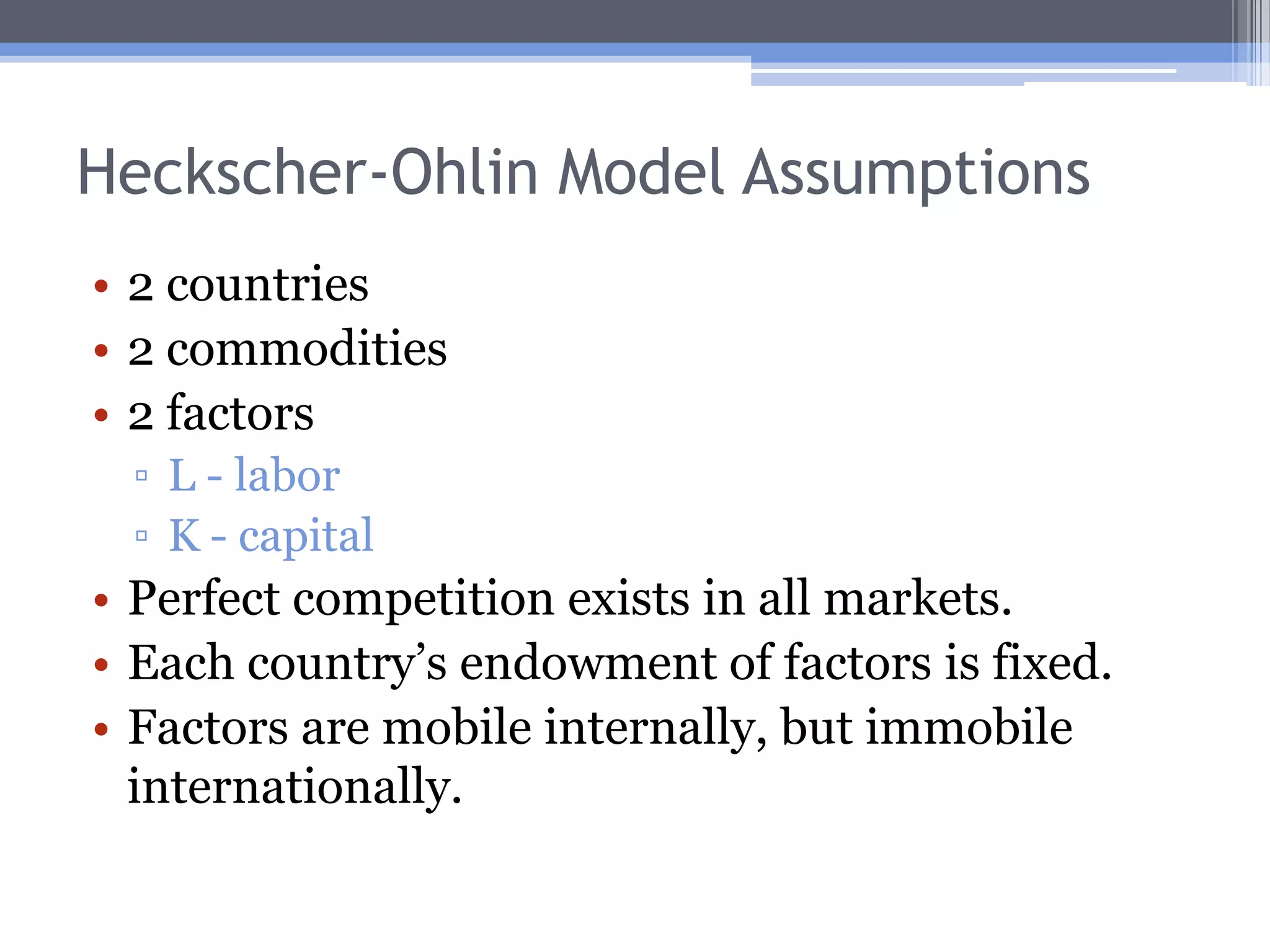

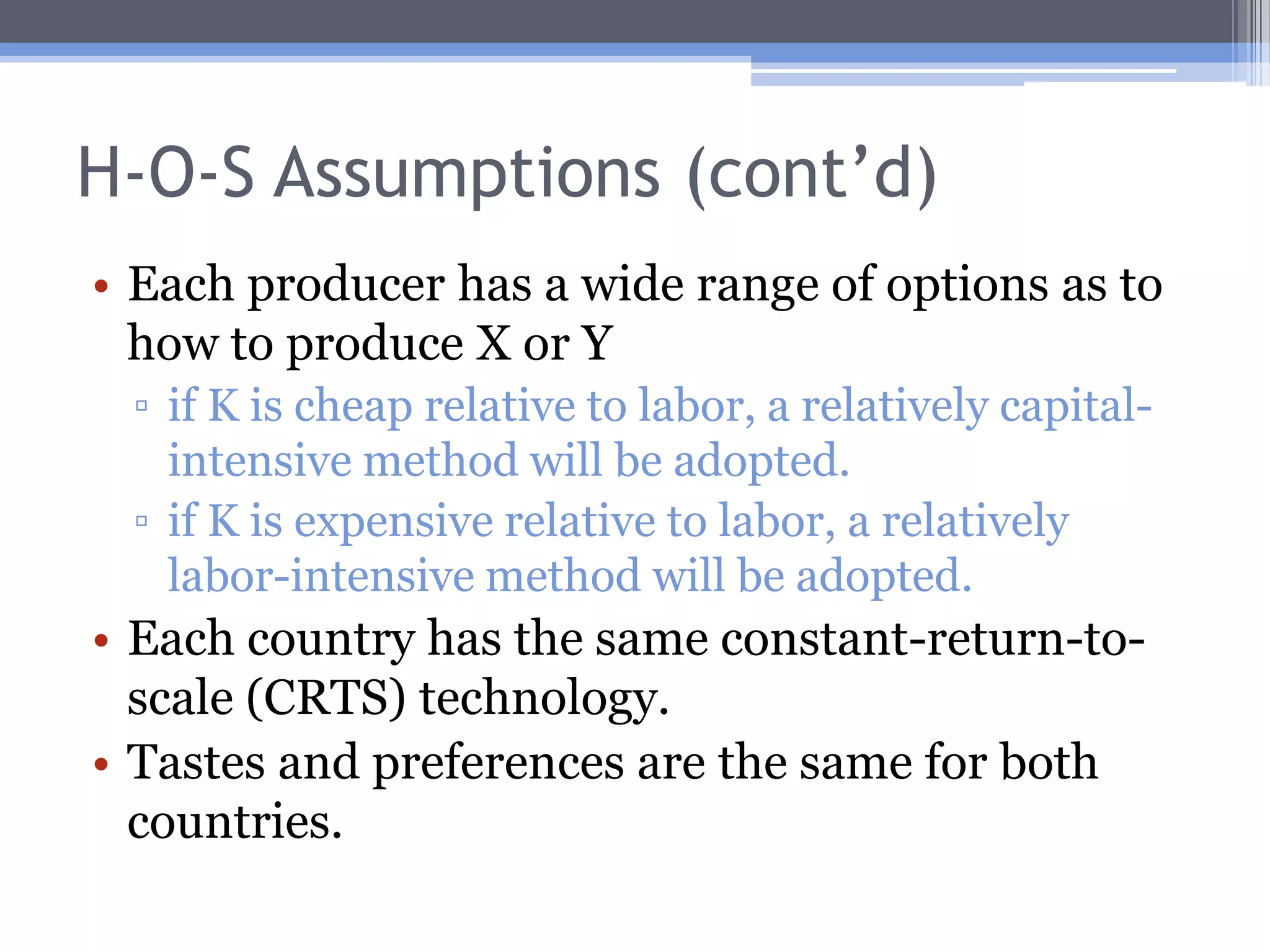

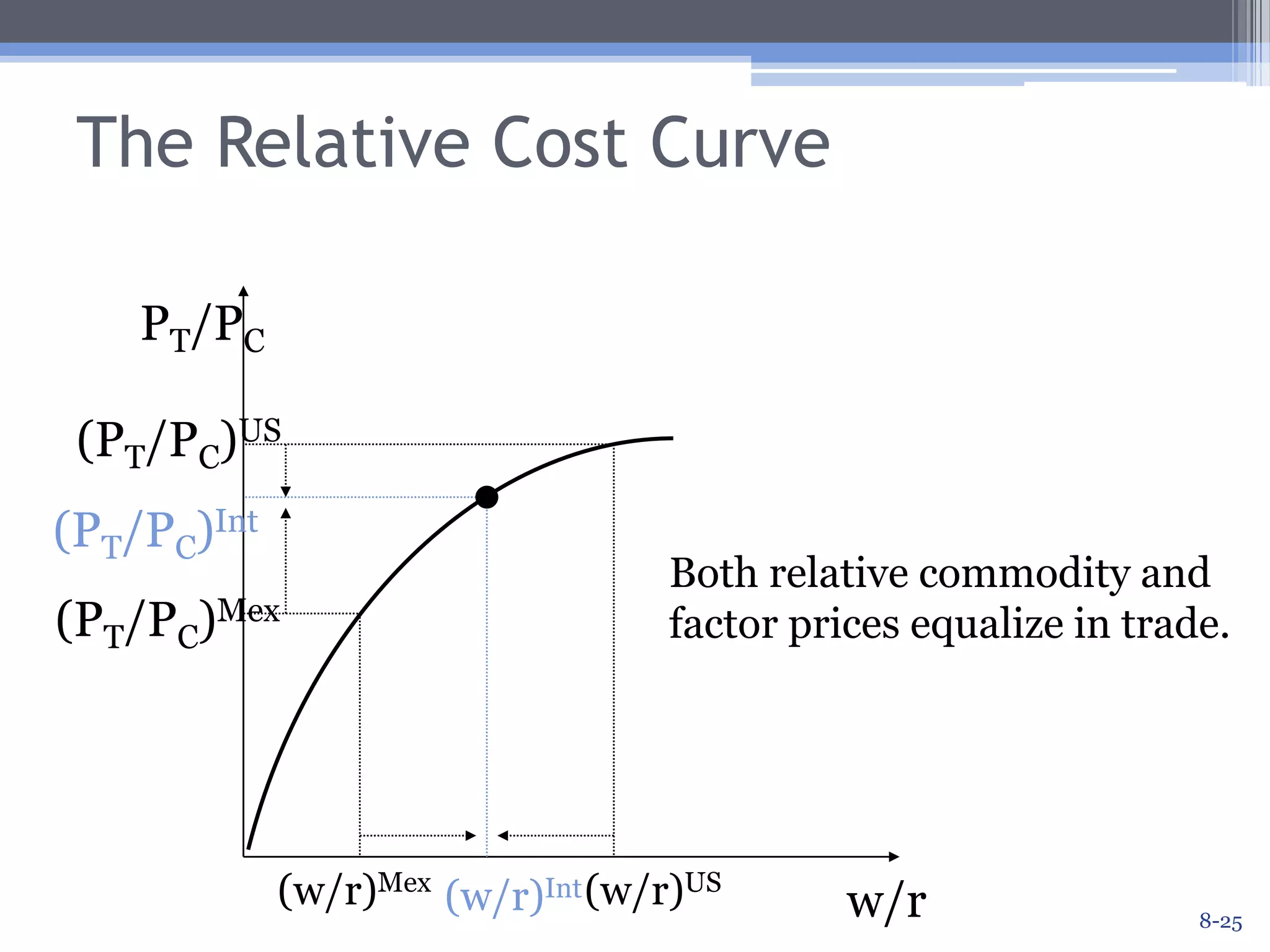

2) It assumes two countries, two goods, and two factors of production. If one country is relatively capital-abundant, it will export capital-intensive goods and import labor-intensive goods.

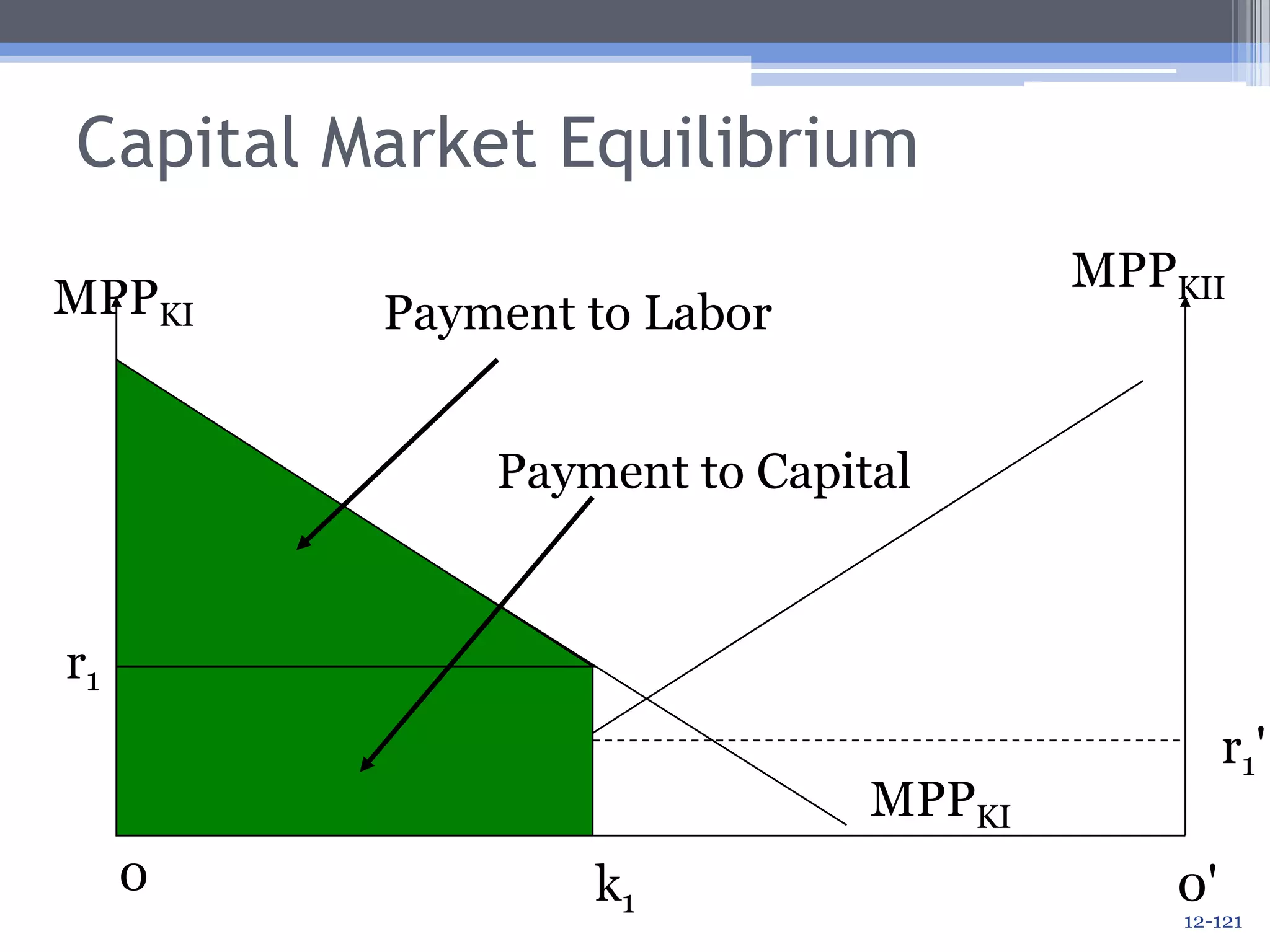

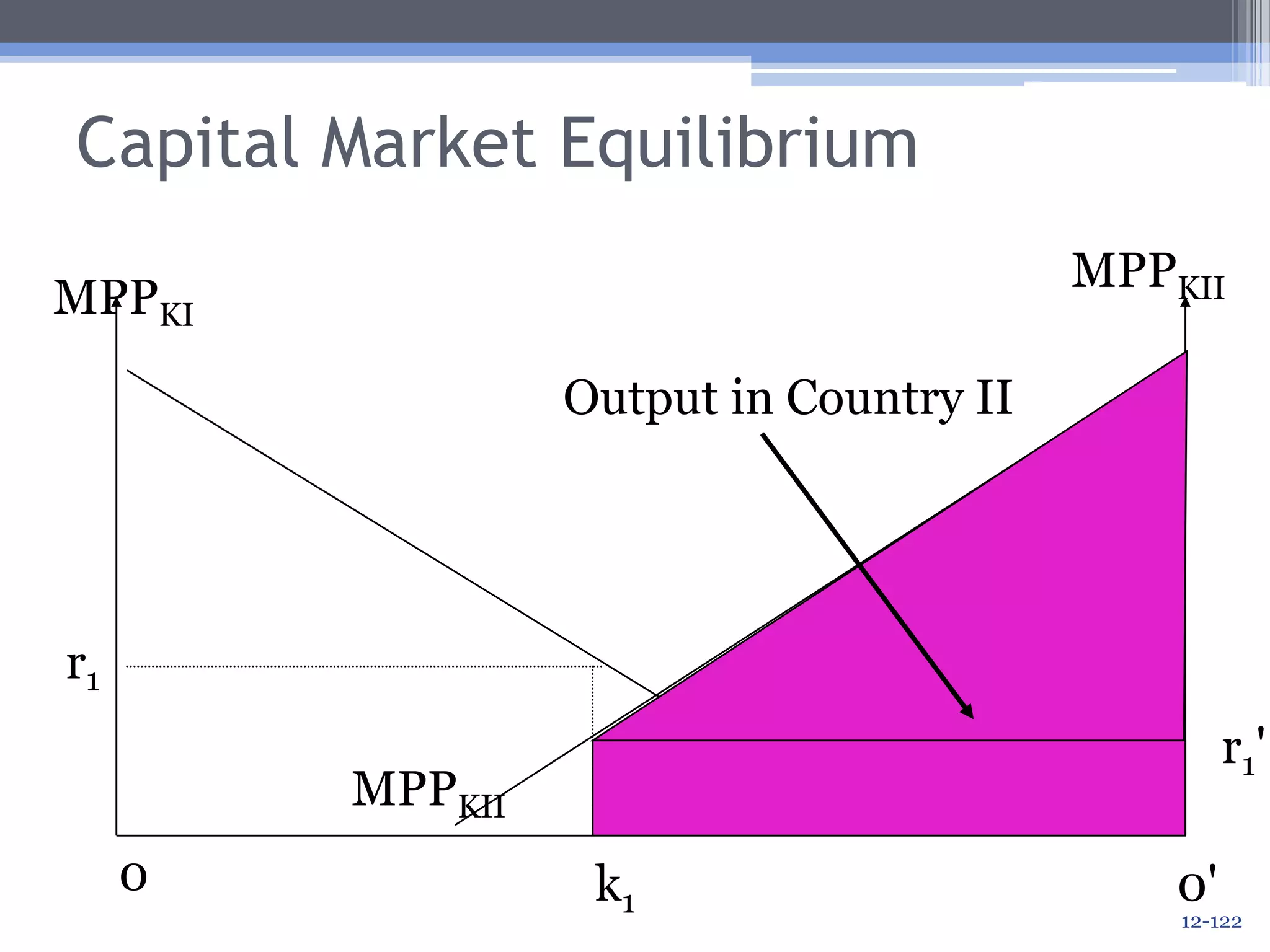

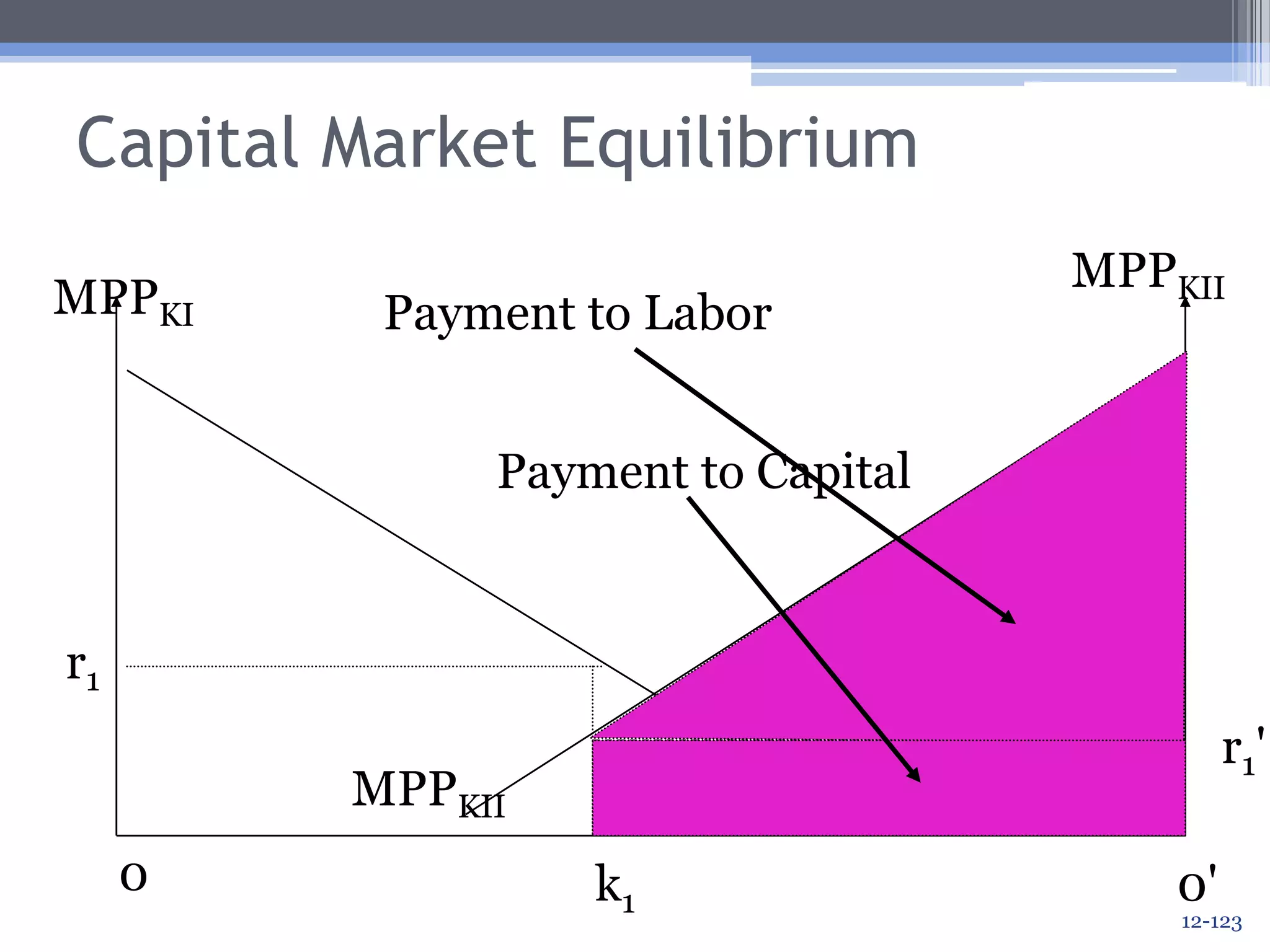

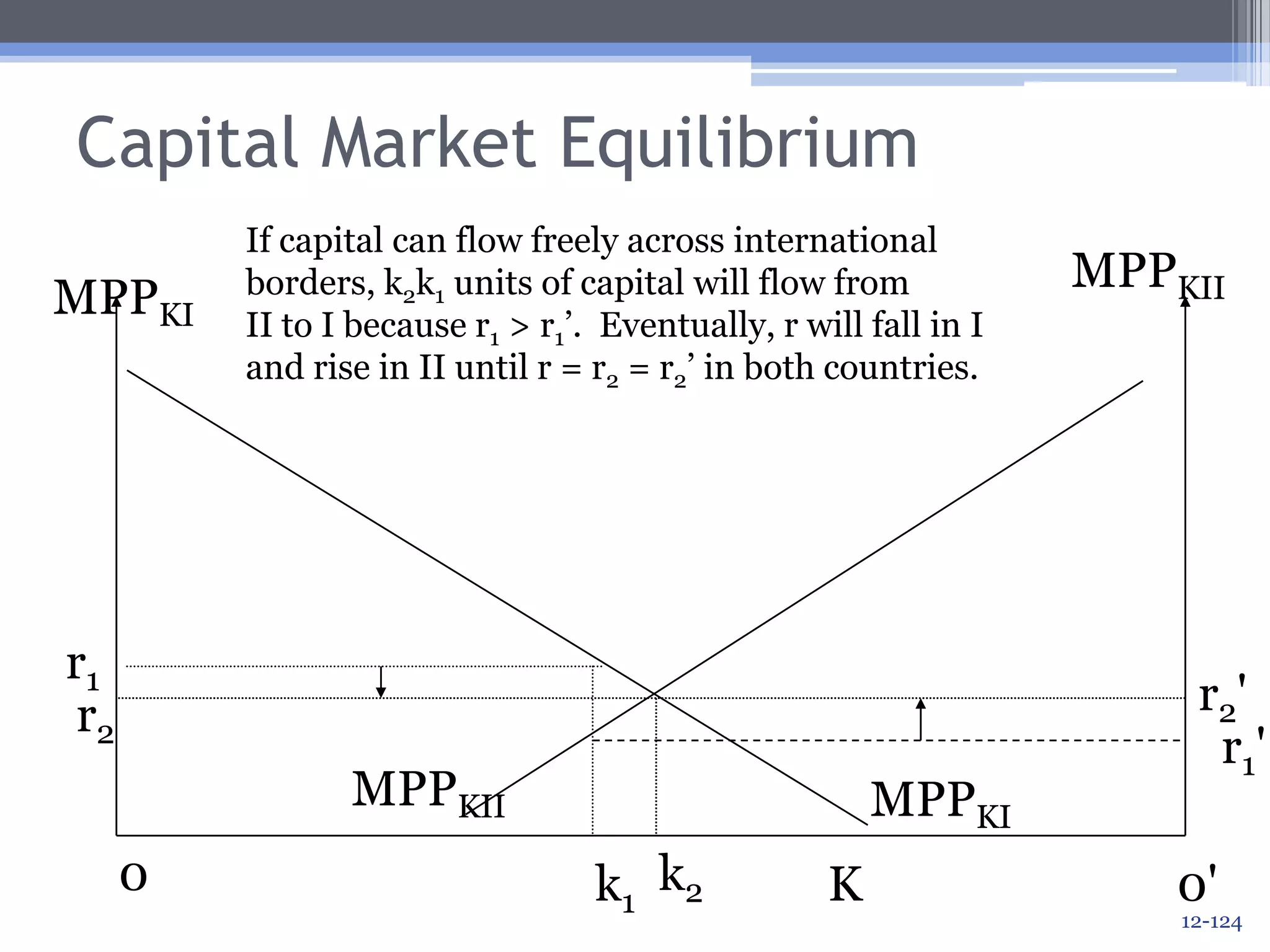

3) The model shows that trade equalizes factor prices between countries. This factor price equalization theorem demonstrates how