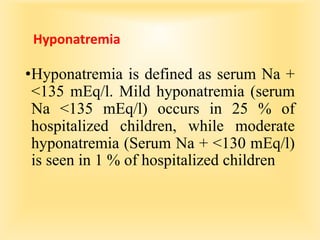

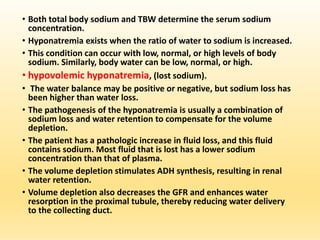

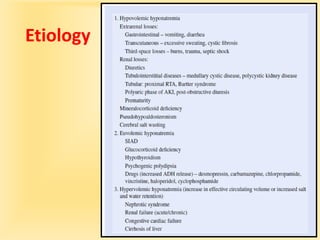

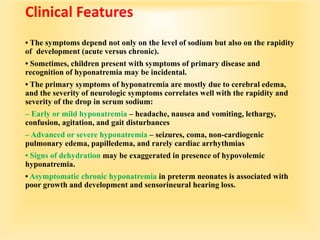

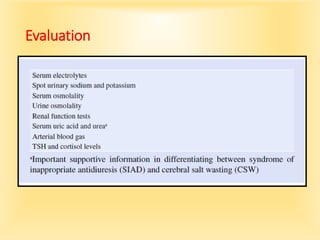

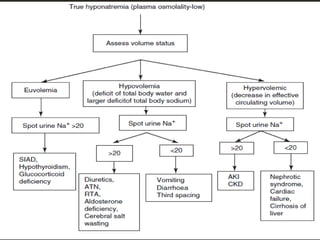

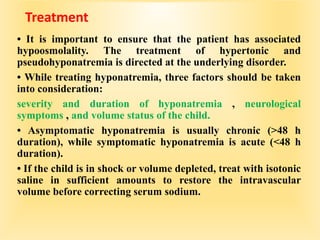

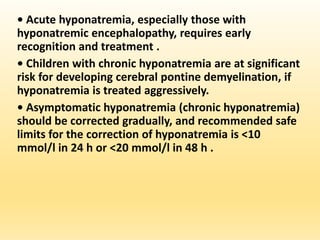

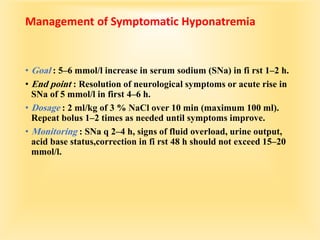

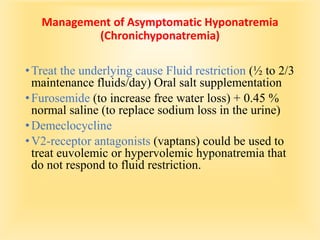

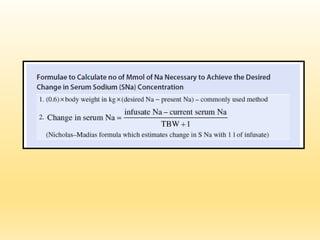

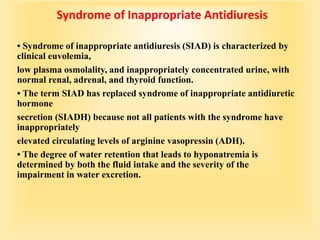

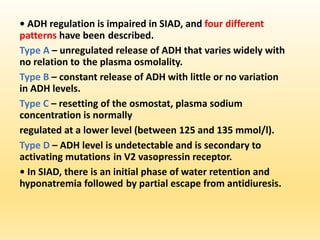

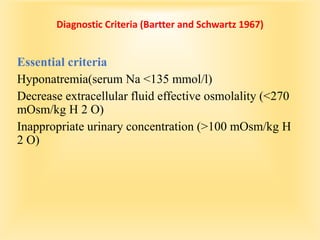

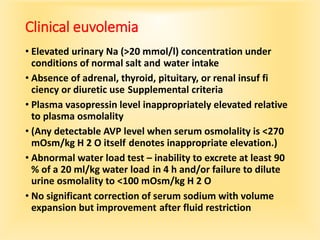

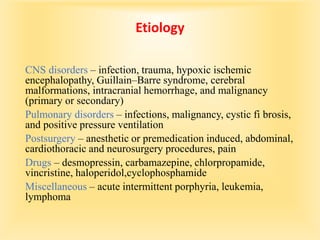

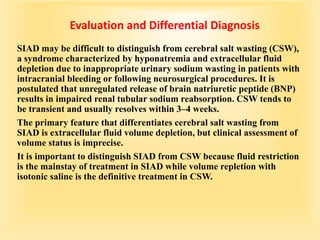

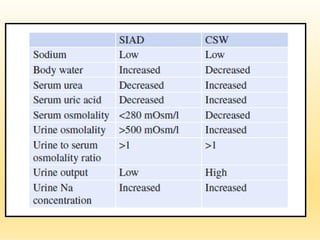

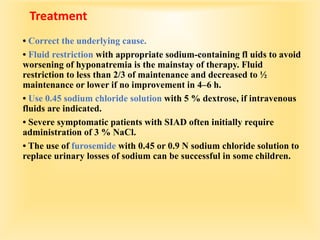

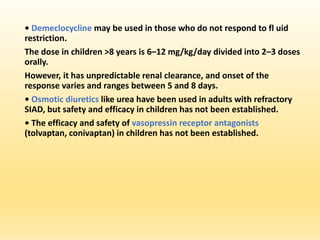

This document discusses hyponatremia, defined as a serum sodium level below 135 mEq/L. Hyponatremia can be hypovolemic, hypervolemic, or euvolemic based on total body water and sodium levels. Causes include sodium loss from the kidneys, adrenal insufficiency, SIADH, and liver or heart failure. Symptoms depend on severity and chronicity, ranging from headache to seizures or coma. Evaluation involves assessing volume status and electrolytes. Treatment involves correcting underlying causes and normalizing sodium levels gradually to avoid osmotic demyelination.