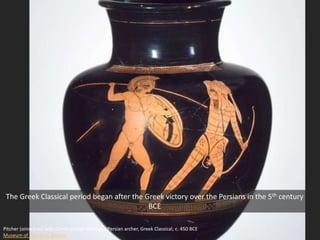

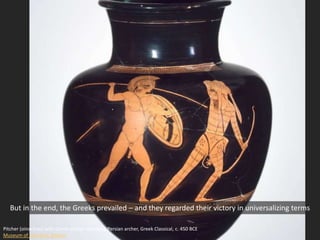

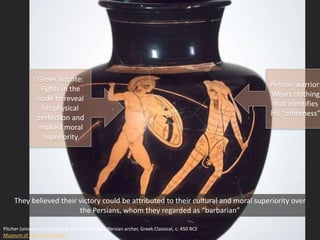

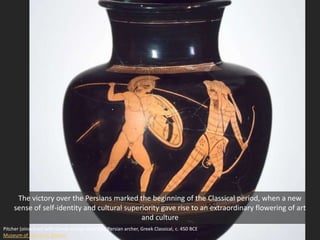

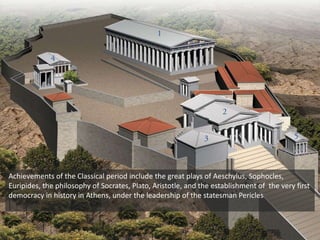

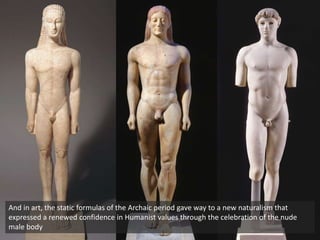

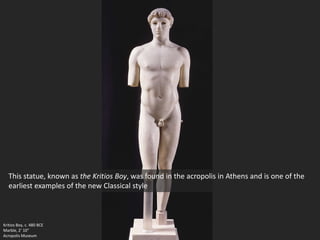

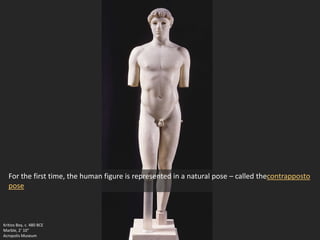

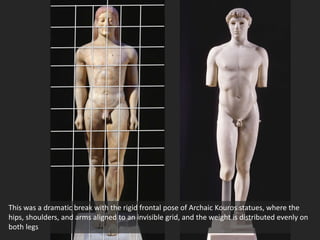

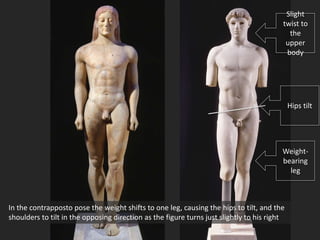

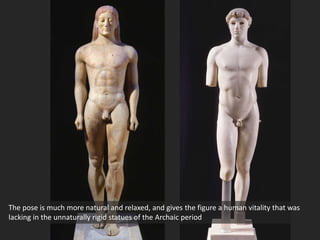

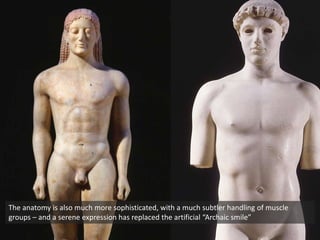

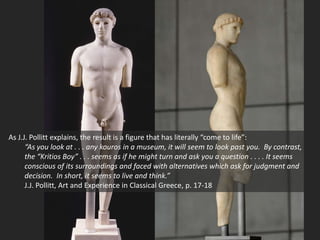

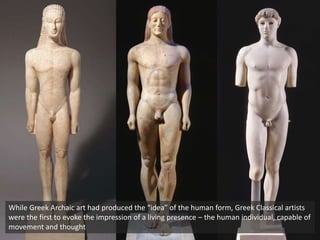

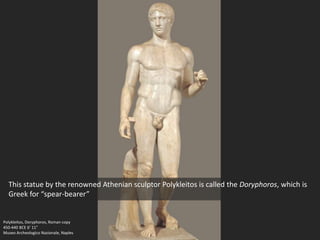

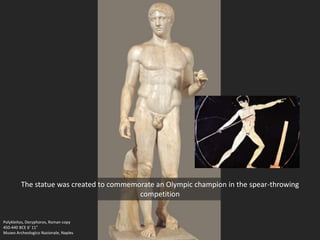

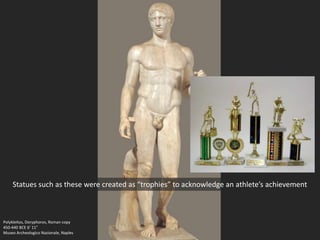

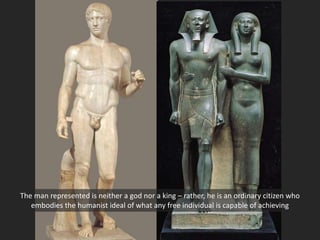

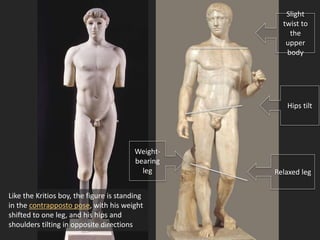

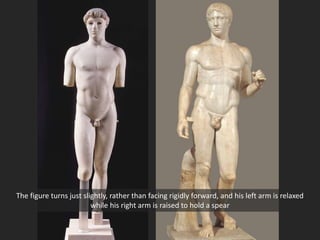

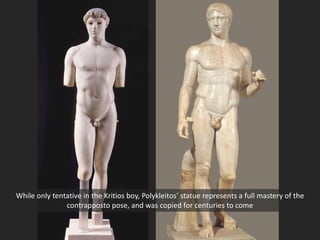

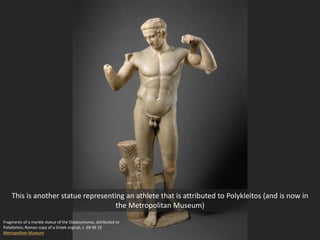

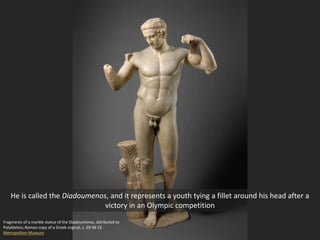

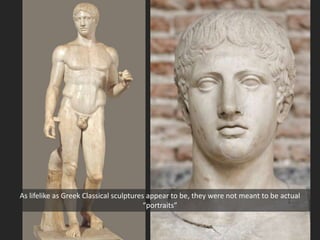

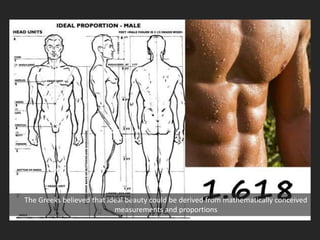

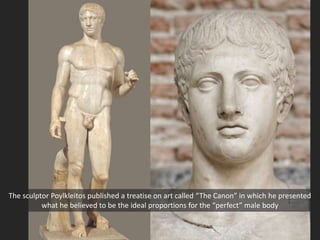

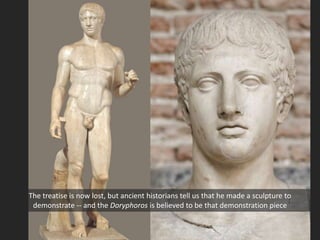

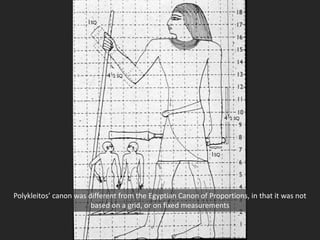

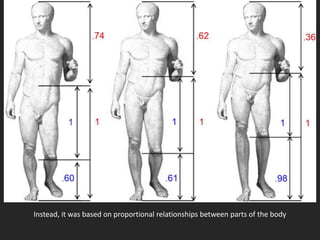

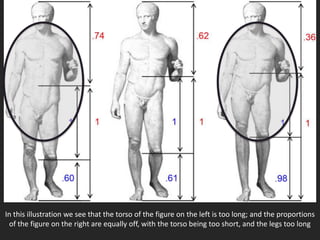

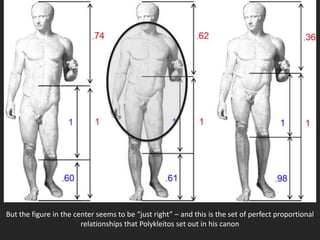

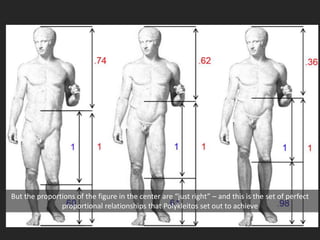

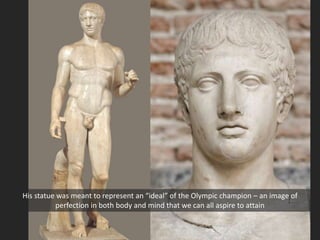

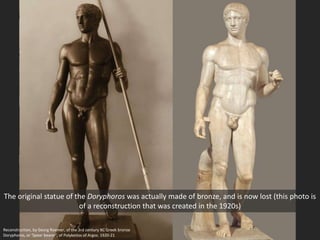

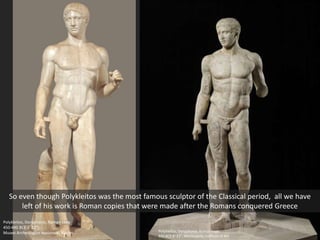

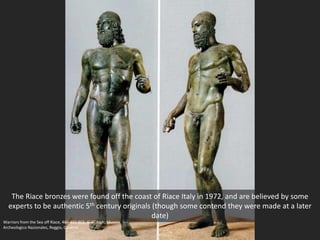

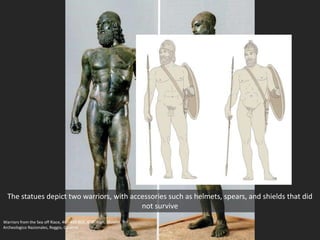

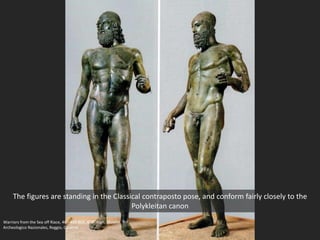

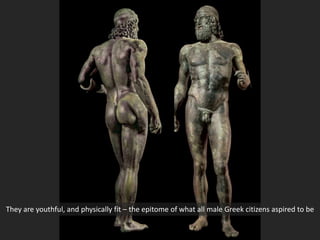

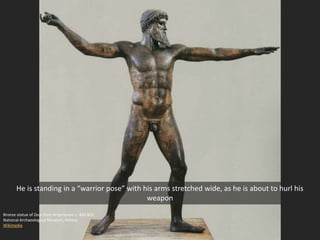

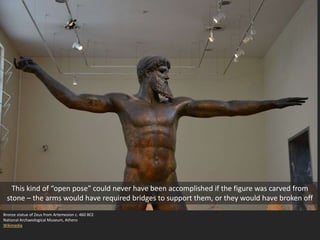

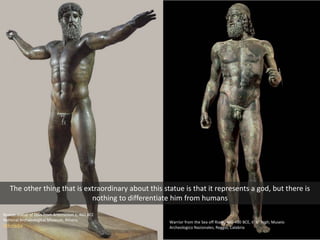

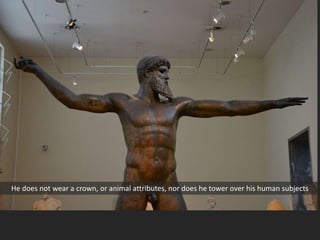

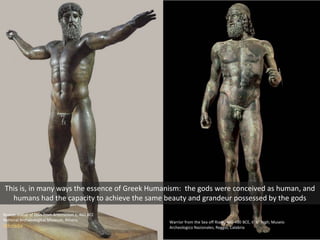

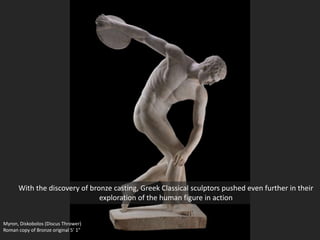

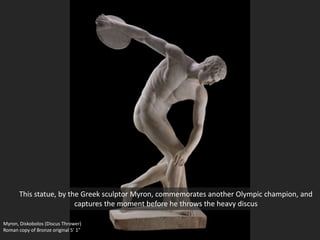

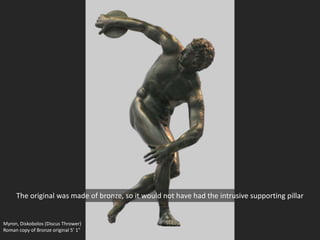

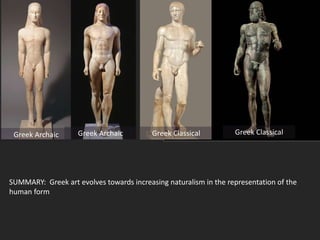

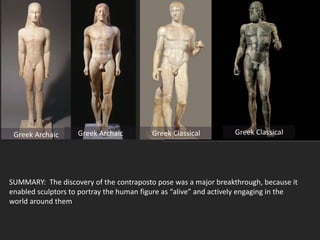

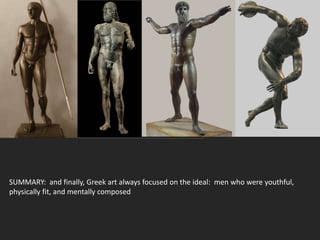

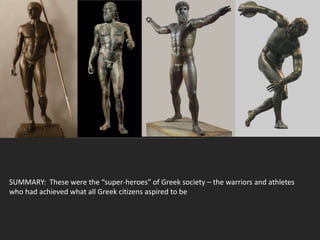

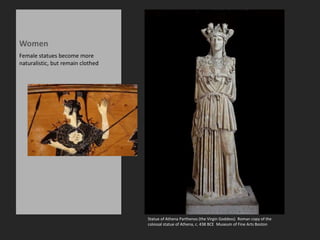

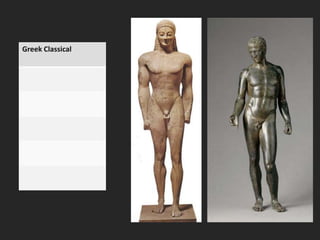

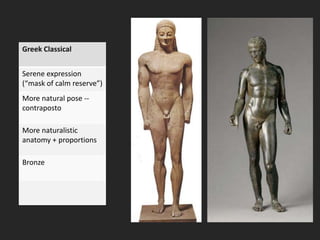

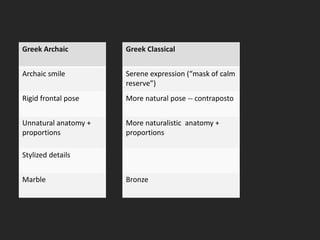

The Greek Classical period began after the Greeks defeated the Persians in the 5th century BCE. During this period, Greek city-states developed a new sense of cultural identity and superiority. Greek Classical sculpture began to depict the human form in a natural and lifelike way, through poses like the contrapposto stance. Artists like Polykleitos created idealized sculptures of the perfect male body that embodied Greek values like strength, fitness, and intellect.