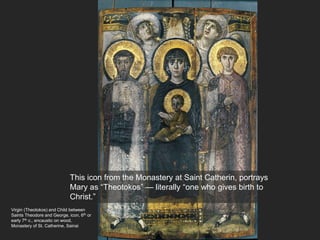

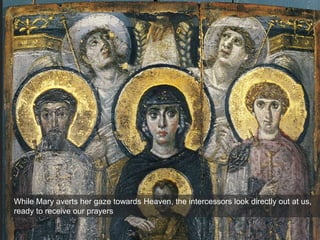

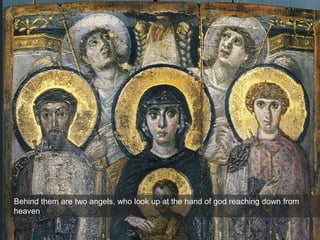

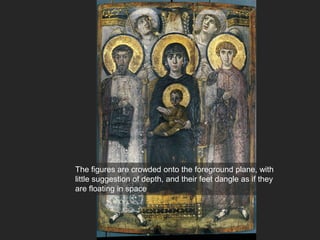

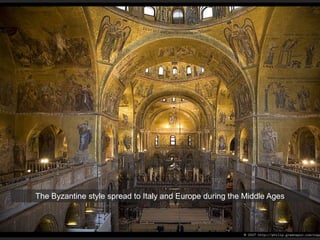

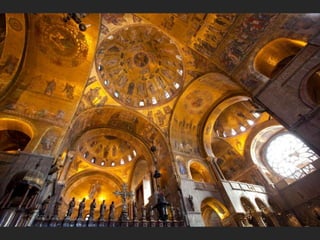

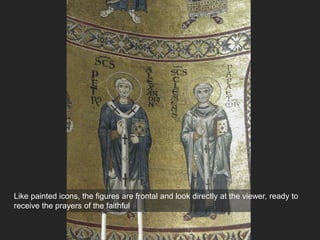

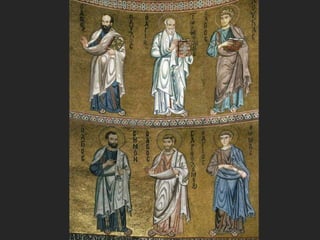

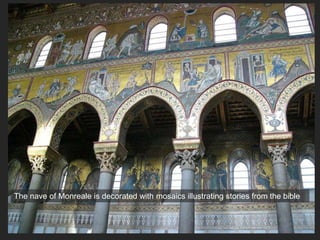

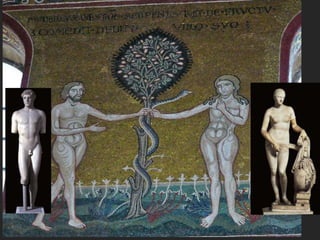

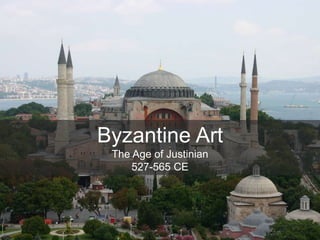

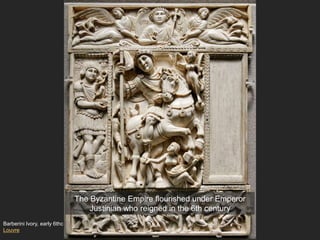

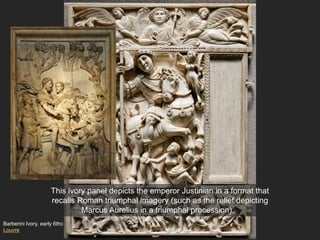

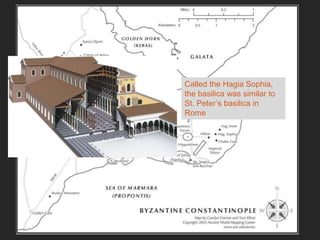

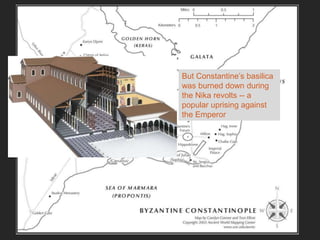

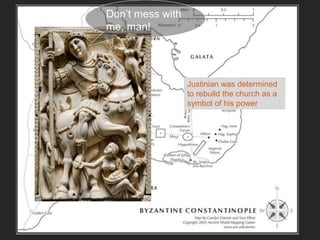

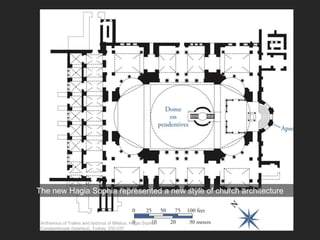

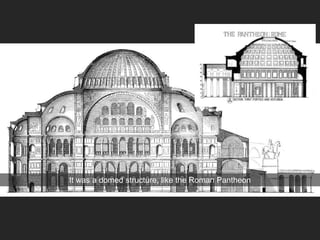

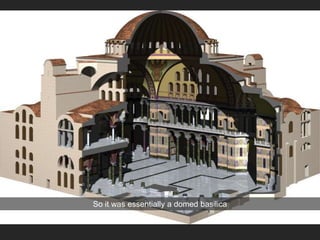

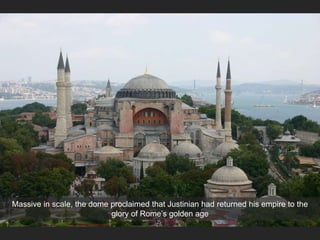

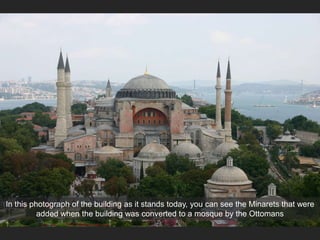

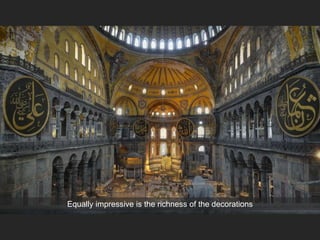

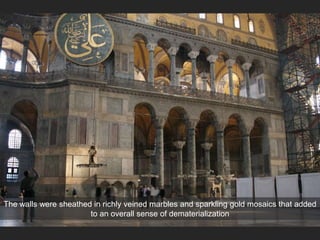

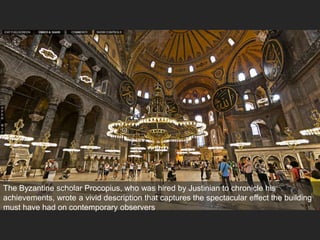

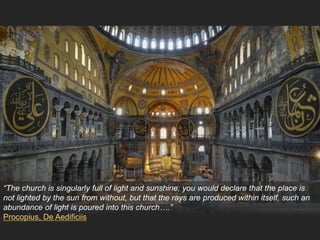

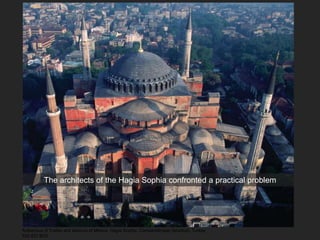

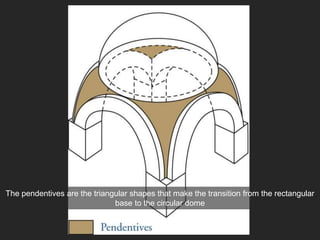

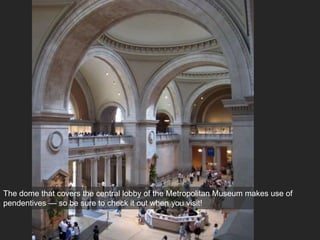

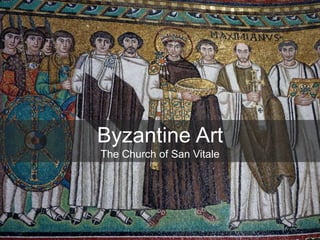

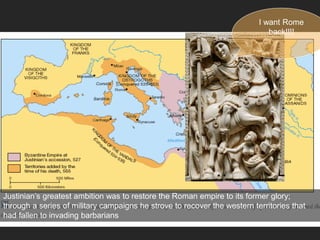

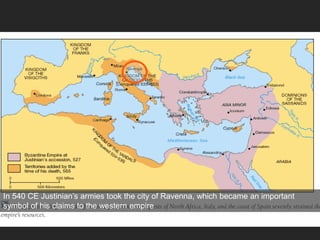

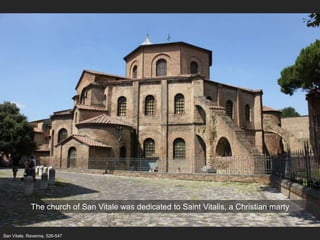

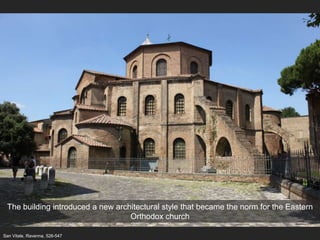

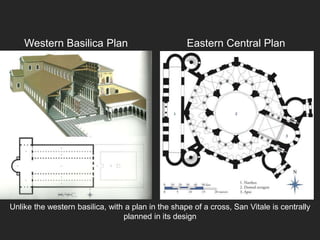

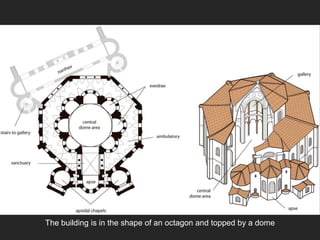

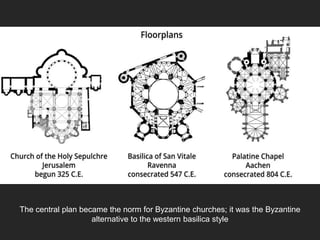

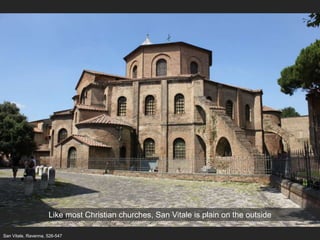

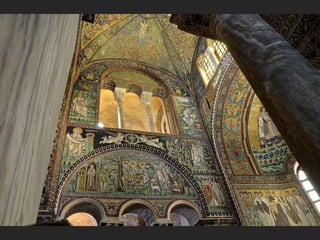

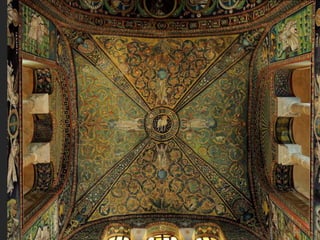

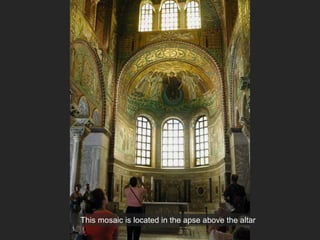

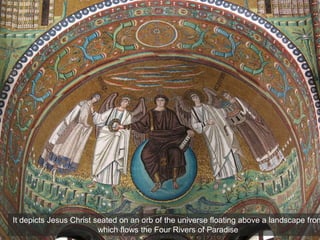

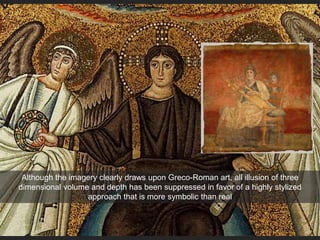

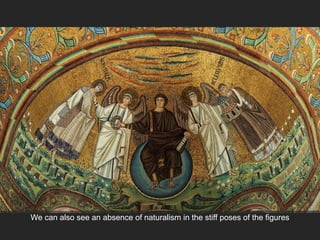

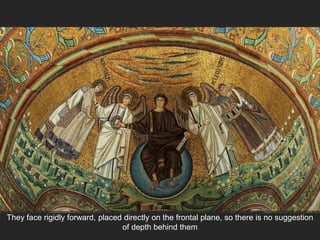

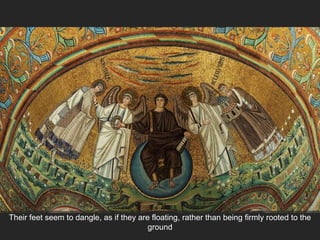

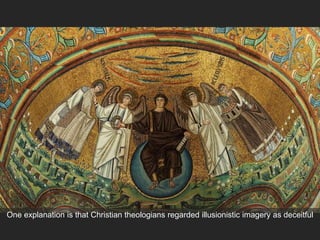

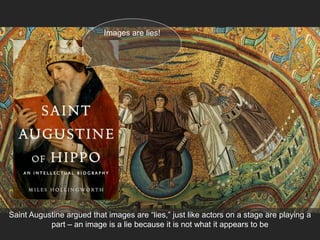

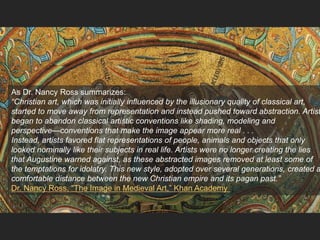

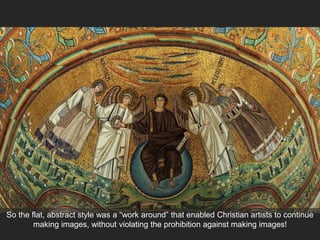

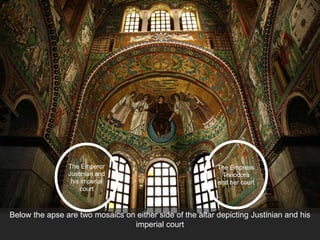

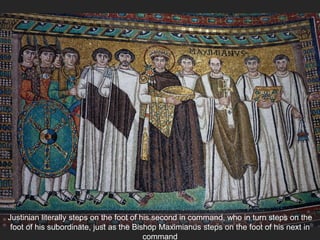

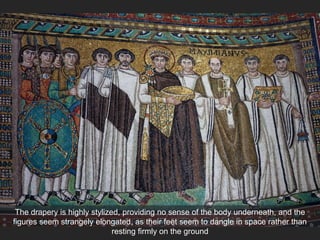

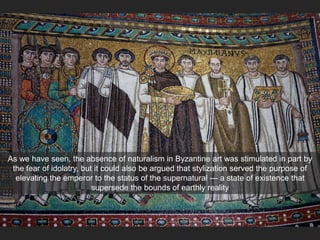

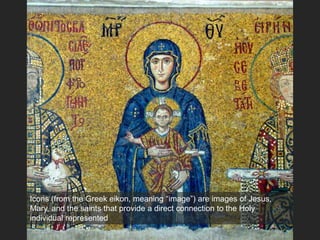

The document provides background information on Byzantine art during the rule of Emperor Justinian from 527-565 CE. It discusses how Justinian sought to restore the Roman Empire to its former glory through military campaigns and sponsored monuments. A key project was the reconstruction of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which featured a central dome structure and was decorated with rich mosaics and marbles. Another important church from this period was the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, which had a central plan and was decorated with lavish biblical mosaics depicting Justinian and religious figures in a stylized, non-naturalistic fashion.

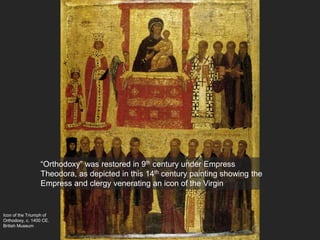

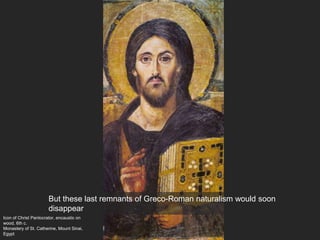

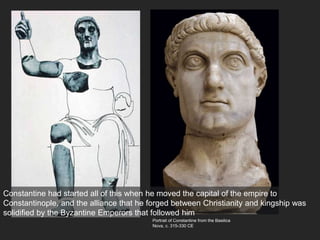

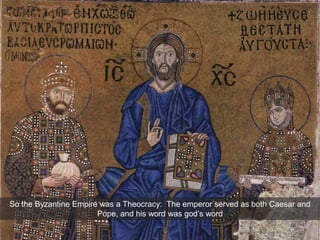

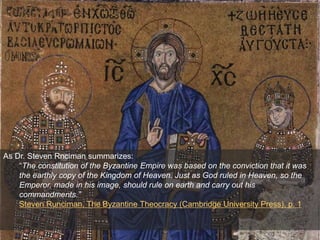

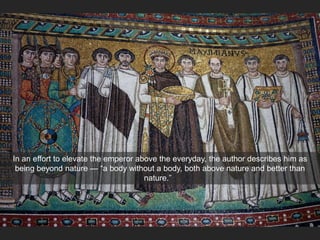

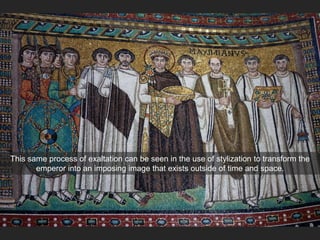

![Consider, for example, this panegyric speech written in praise the emperor Constantine

IX:

“Shall I, then, compare you to someone? But whoever could make you a subject of

comparison, you who are so great and above compare?… For you have outdone

nature, and have become closest to the ranks of the spiritual beings . . . How

therefore shall we complete your portrait…? For you are to some extent a being

with a body and without a body, both above nature and better than nature. We

compare you, therefore, to the finest of bodies and to the more immeasurable of

those without bodies.”[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7-170817185748/85/Byzantine-Art-102-320.jpg)

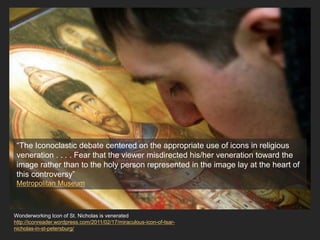

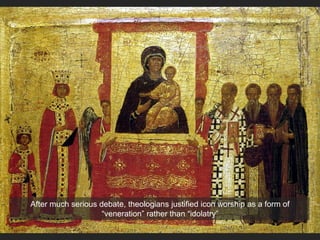

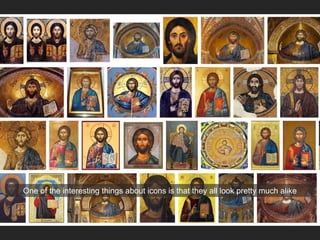

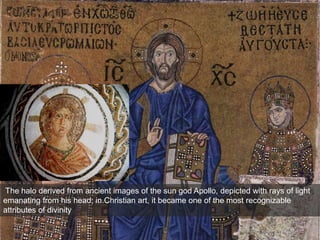

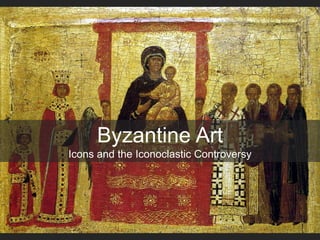

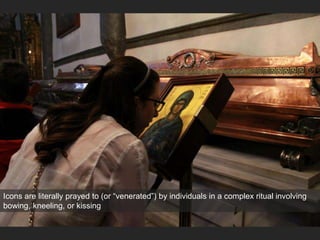

![Wonderworking Icon of St. Nicholas is venerated

http://iconreader.wordpress.com/2011/02/17/miraculous-icon-of-tsar-

nicholas-in-st-petersburg/

The eighth-century theologian John of Damascus urged the faithful to ”embrace

[icons] with the eyes, the lips, the heart, bow before them, love them . . .” (NGA)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7-170817185748/85/Byzantine-Art-109-320.jpg)