This document provides an overview of a publication containing papers from the Symposium on Geophysical Methods for Geotechnical Investigations. The publication covers both surface and borehole geophysical techniques applied to environmental and geotechnical engineering problems. Surface methods provide horizontal maps or vertical profiles of subsurface properties, while borehole methods provide continuous vertical logs of properties along boreholes. Together, surface and borehole methods provide complementary data for characterizing geological formations and groundwater.

![STP1101-EB/Oct. 1990

Overview

The latest environmental concerns related to contamination from landfills and other dis-

posal sites, along with the need for improved evaluation of the mechanical properties of

soils and other geological substrates in civil engineering, have greatly increased the interest

in the application of geophysics in geotechnical investigations. Geophysics provides the

means to probe the properties of soils, sediments, and rock outcrops without costly exca-

vation. The nonintrusive sampling of geological formations is important because extensive

disturbance of these deposits could compromise the integrity of a natural geological migration

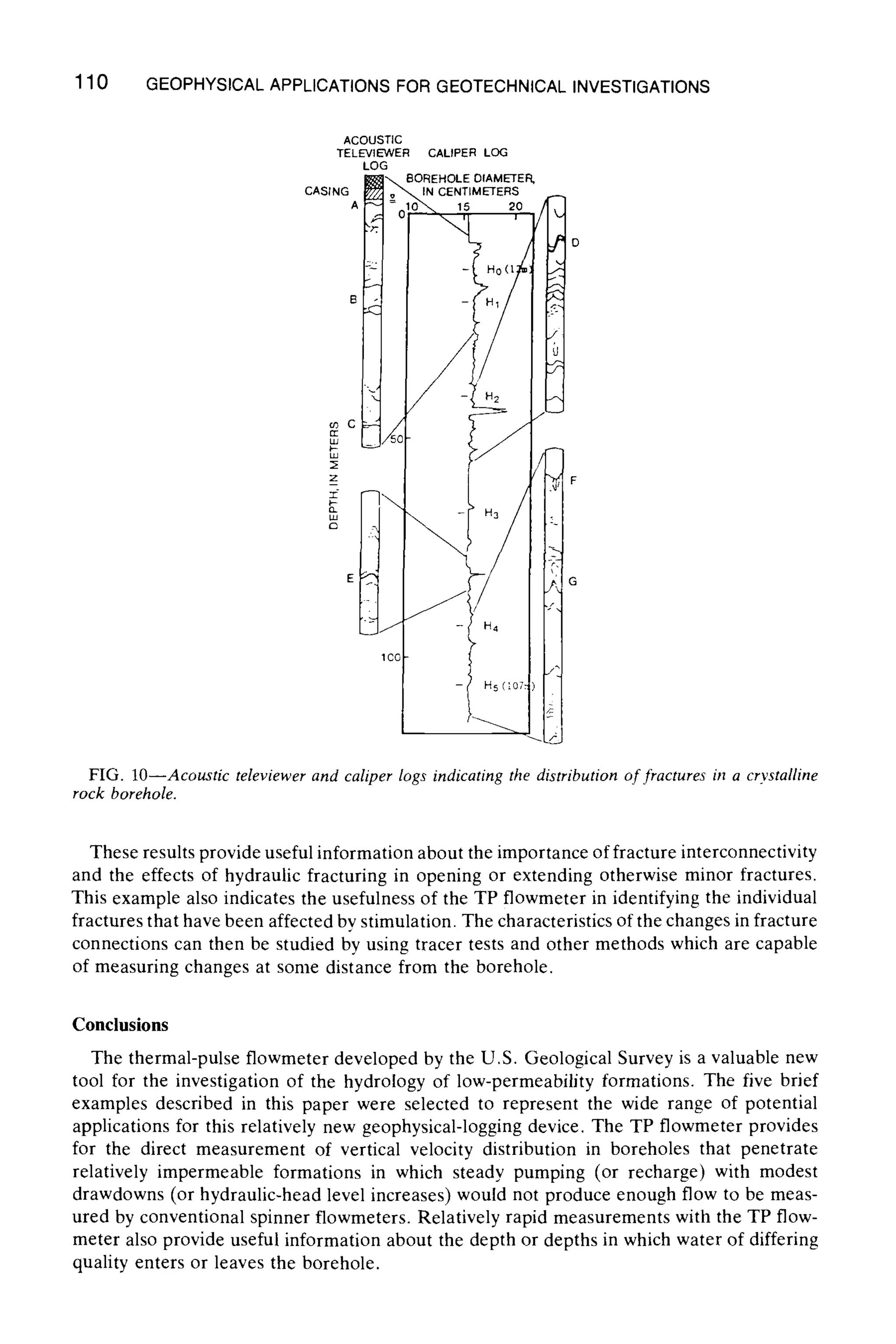

barrier or foundation site. Moreover, many physical properties of importance in engineering

such as density, porosity, permeability, and shear modulus are highly sensitive to in-situ

conditions. Relief of overburden stress, shearing, and desiccation associated with sample

retrieval can significantly alter the measured properties of sediments. On the other hand,

most geophysical methods involve the measurement of physical properties such as acoustic

velocity or electrical conductivity that are. different from those needed for engineering

studies. In the ideal situation, laboratory analysis of a finite number Of carefully extracted

samples can be used in conjunction with continuous geophysical surveys to produce a two-

or three-dimensional map of the area of interest.

More than 25 years ago, ASTM Committee D-18 on Soil and Rock indicated an interest

in geophysical methods by including several papers on both borehole and surface geophysical

applications in a symposium on Soil Exploration [1]. Even earlier (1951), ASTM Committee

D-18 sponsored a symposium on Surface and Subsurface Reconnaissance [2] in which the

subsequent STP contained 8 papers and a panel discussion related to surface geophysics

techniques and applications in engineering site investigations.

This present volume presents a series of papers originally given at the ASTM Symposium

on Geophysical Methods for Geotechnical Investigations held on 29 June 1989 in St. Louis,

Missouri. The papers were selected to provide a broad overview of the latest geophysical

techniques being applied to environmental and geotechnical engineering problems. Such

geophysical methods have traditionally been divided into those applied at the land surface

to generate two-dimensional maps of geophysical properties and those applied in boreholes

to generate one-dimensional maps, or "logs," of geophysical properties along the length of

the borehole. The two approaches yield complementary results because the geophysical well

logs provide much greater spatial resolution (usually on the order of a metre) in comparison

with the surface soundings (where resolution is on the order of 10 to 100 m). When surface

methods result in soundings plotted as a vertical cross section of the formation, geophysical

logs can be used to calibrate the depth scale in the surface-generated data section.

In the latest geophysical technology, the distinction between surface and borehole methods

has become somewhat blurred. Borehole-to-borehole and surface-to-borehole soundings are

now being used to generate three-dimensional images of the rock volume between boreholes

Copyright* 1990by ASTM International

1

www.astm.org](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-6-2048.jpg)

![OVERVIEW 3

orientated logging technology to environmental and hydrological studies. A decade later

the accelerating interest in environmental issues and radioactive waste disposal prompted

interest in designing logging equipment for various specific environmental and engineering

applications. The recent proliferation of microprocessors and solid state electronics has

further increased the flexibility available in logging for geotechnical applications. Today,

geotechnical logging equipment includes sources and transducers designed to measure prop-

erties of interest in engineering and hydrology, compensated probe configurations equivalent

to the most sophisticated used in the petroleum industry, downhole digitization of geophysical

measurements, and uphole processing of log data. All of these trends indicate that in the

future geophysical logging will become an important tool in many kinds of geotechnical

studies in which logging has not usually been considered relevant in the past.

The papers included in this volume were selected to give a representative cross section

of the latest equipment designs and data analysis techniques being made available to the

hydrologist and civil engineer. The overview of logging logistics and economics by Crowder

provides an instructive introduction into the role of borehole geophysics in environmental

studies. One of the most important issues is related to time and efficiency. Complete coring

provides a direct sampling of formations, but simple drilling and logging provides most of

the information in a fraction of the time and at substantially reduced costs. A carefully

thought-out combination of sampling, drilling, and logging clearly has an important role in

such studies and may sometimes be the only way in which a study can be completed to meet

schedules imposed by legal and operational constraints.

The papers by Jorgensen and Burns describe some of the most recent developments in

relating geophysical measurements in boreholes to the specific sediments properties of in-

terest in engineering and hydrology. Burns describes the information that can be derived

from the most advanced acoustic logging techniques. Not only are the seismic velocities of

sediments directly related to the mechanical properties (dynamic rather than static), but

acoustic measurements can sometimes be related to formation permeability. The latest

acoustic studies show that new transducer designs may greatly improve the ability to make

mechanical property and permeability measurements in situ. The paper by Jorgensen pre-

sents a review of the methods which may be used to infer the quality of water present in

the formation. In many situations, these methods can be used to produce a qualitative or

semi-quantitative profile of contaminant distribution adjacent to the borehole. If additional

information is available under the proper circumstances, these qualitative measurements

can be turned into estimates of solute content. The interested reader can consult the ref-

erences listed by these papers, especially the earlier review by Alger [3], the case study by

Dyck et al. [4], or the recent review by Alger and Harrison [5].

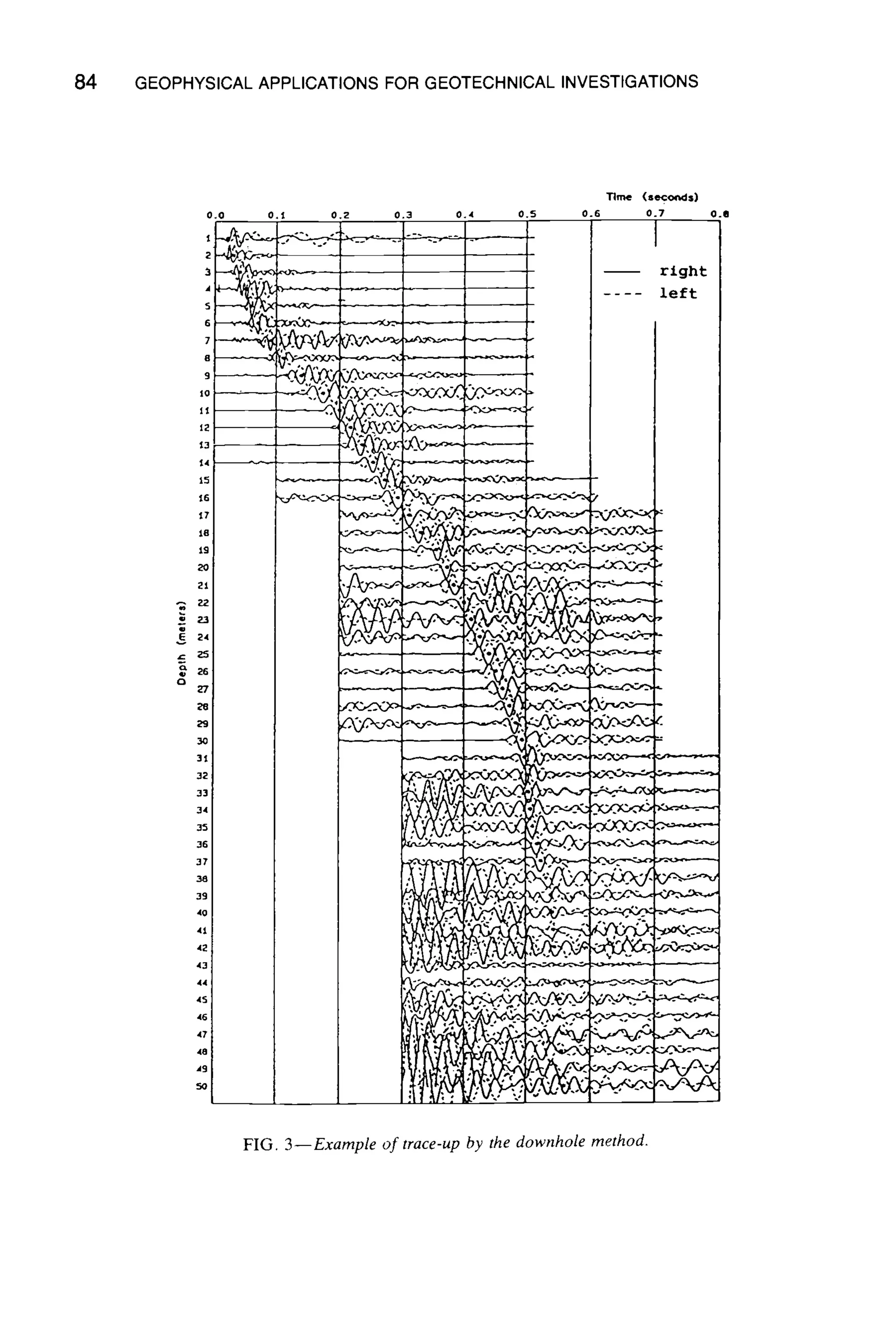

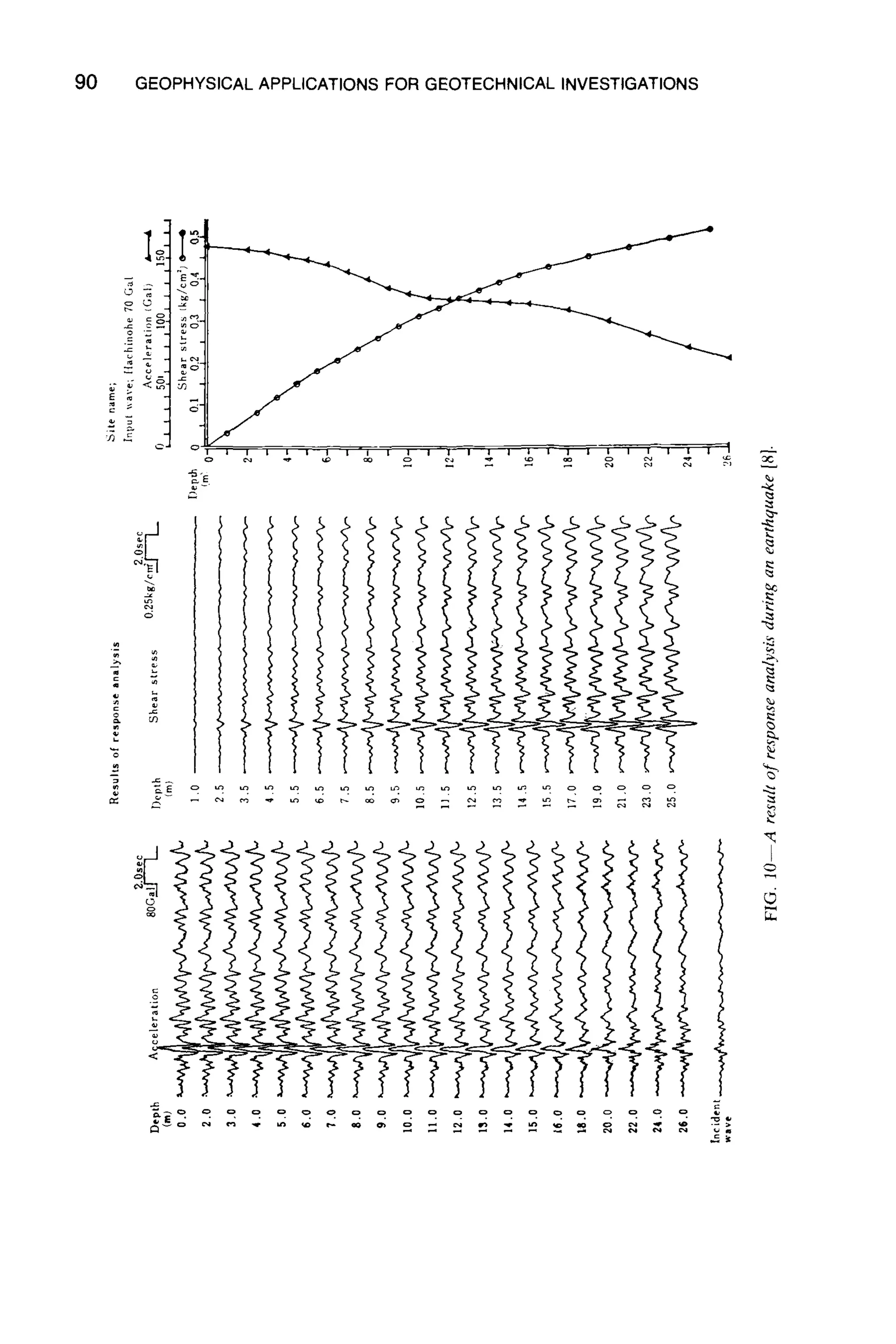

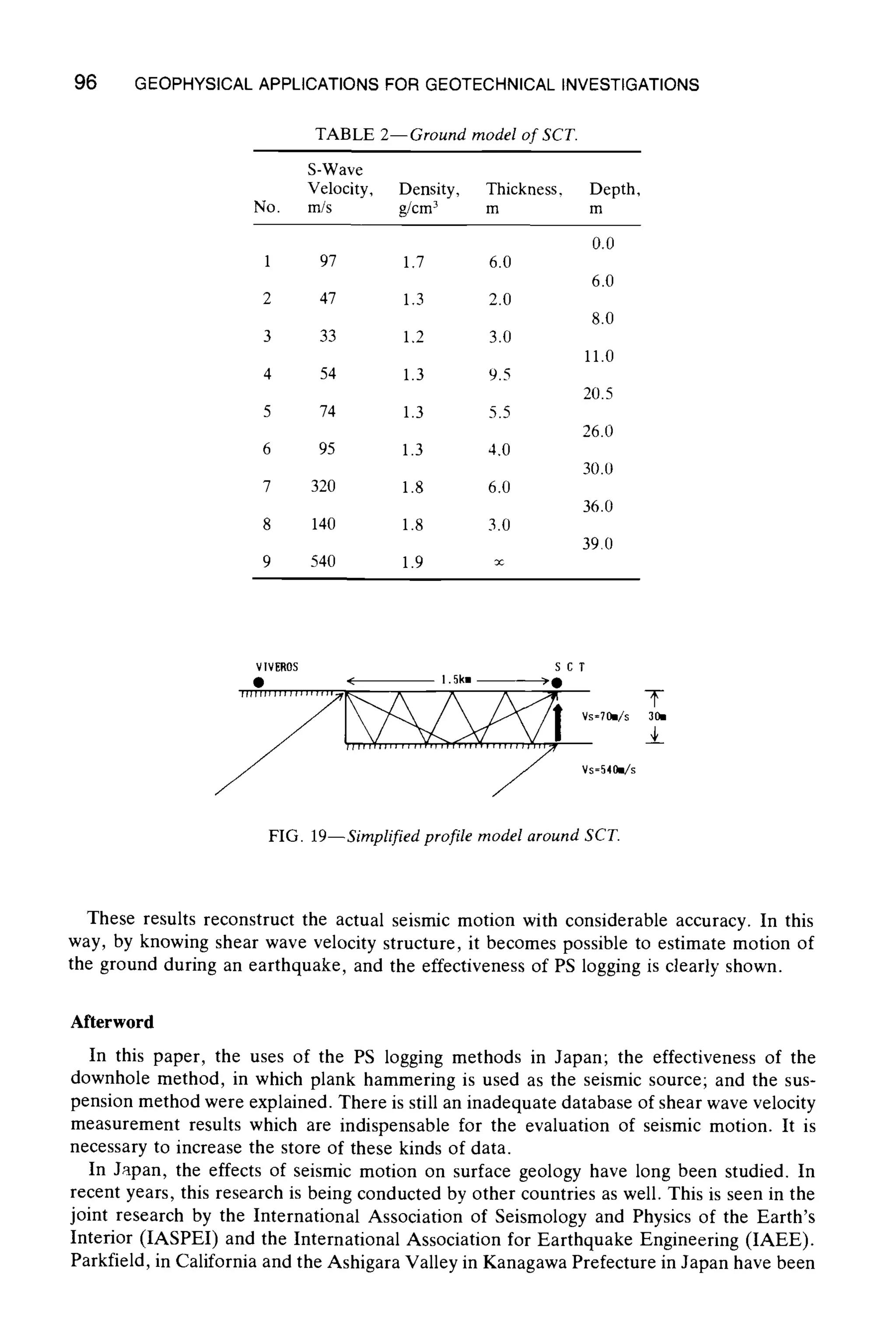

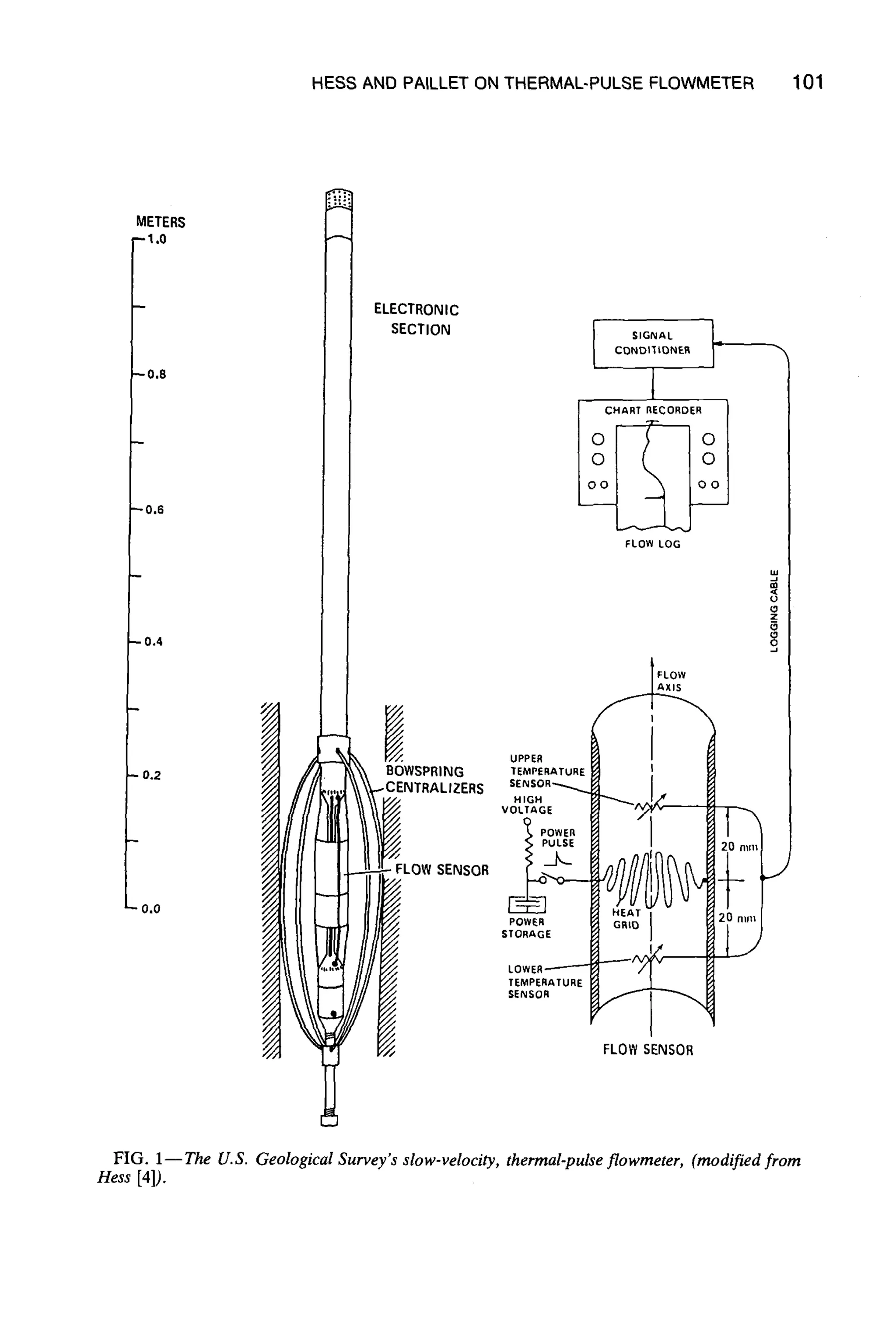

The papers by Kaneko et al. and Hess and Paillet each present a specific logging tool

developed to address geotechnical applications. Hess and Paillet describe a recently devel-

oped flowmeter logging system capable of measuring vertical flows in boreholes with much

greater resolution than available by means of conventional spinner flowmeters. This device

has important applications in identifying the location of inflows and exit flows in boreholes

under stressed and unstressed conditions, providing useful information on the source of

waters sampled from test wells and on the distribution of permeability in tight or fractured

formations. The significance of high-resolution flowmeter data in identifying the movement

of water in fractured crystalline rocks is indicated by such studies as Hess [6], Paillet et al.

[7], and Paillet [8].

The paper by Kaneko et al. emphasizes the interpretation of the shear modulus of soils

in situ by what appears to be standard geophysical logging methods. However, the approach

is based on a relatively new transducer design [9] developed especially for such engineering](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-8-2048.jpg)

![4 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONSFOR GEOTECHNICALINVESTIGATIONS

applications. This source configuration was but the first of many such applications of acoustic

logging with nonaxisymmetric sources [10,11]. The paper in this volume indicates the use

of these low-frequency shear measurements in boreholes; some of the future applications

for this developing method are also mentioned by Burns.

The five papers on borehole geophysics applications in geotechnical studies included in

this volume are but a small sample of the proliferating technologies becoming available to

modern geoscientists and engineers. Additional information on geotechnical applications of

logging can be found in the two recent monographs by Keys [12] and Hearst and Nelson

[13] and in the paper by Keys [14]. We hope that these four papers in this volume serve as

examples indicating a number of important ways in which borehole geophysics can contribute

to geotechnical studies, and that they stimulate the reader to investigate the broader pos-

sibilities of geophysical logging in the future.

Contributions made by the authors and technical reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

The editors also express appreciation to the ASTM staff and officers of ASTM Committee

D-18 for their assistance and support in organizing and publishing these papers resulting

from the symposium.

Frederick L. Paillet

U.S. Geological Survey

Denver, CO; symposium

co-chairman and co-editor

Wayne R. Saunders

ICF-Kaiser Inc.

Fairfax, VA; symposium

co-chairman and co-editor

References

[1] Gnaedinger, G. P. and Johnson, A. I., Eds., Symposium on Soil Exploration, ASTM STP 351,

American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, 1964.

[2] McAlpin, G. W. and Gregg, L. E., Eds., Symposium on Surface and Subsurface Reconnaissance,

ASTM STP 122, American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, 1951.

[3] Alger, REP., "Interpretationof Electric Logs inFresh Water Wellsin Unconsolidated Formation,"

Society of Professional Well Log Analysts 7th Annual Logging Symposium, Transactions, Tulsa,

OK, 1966, pp. CC1-CC25.

[4] Dyck, J. H., Keys, W. S., and Meneley, W. A., "Application of Geophysical Loggingto Ground-

water Studies in Southern Saskatchewan," Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 1,

1972, pp. 78-94.

[5] Alger, REP. and Harrison, C. W., "Improved Fresh Water Assessment in Sand Aquifers Utilizing

Geophysical Well Logs," The Log Analyst, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1989, pp. 31-44.

[61 Hess, A. E., "Identifying Hydraulically-Conductive Fractures with a Low-VelocityBorehole Flow-

meter," Canadian Geotechnical Journal, Vol. 23, 1986, pp. 69-78.

[7] Paillet, F. L., Hess, A. E., Cheng, C. H., and Hardin, E. L., "Characterization of Fracture

Permeabilitywith High-ResolutionVerticalFlowMeasurements during Borehole Pumping," Ground

Water, Vol. 25, No. 1, 1987, pp. 28-40.

[8] Paillet, F. L., "Analysis of Geophysical Well Logs and Flowmeter Measurements in Boreholes

Penetrating Subhorizontal Fracture Zones: Lac Du Bonnet Batholith, Manitoba, Canada," Water

Resources Investigations Report 89-4211, U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, CO, 1990, in press.

[9] Kitsunesaki, C., "A New Method for Shear Wave Logging," Geophysics, Vol. 45, 1980,pp. 1489-

1506.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-9-2048.jpg)

![OVERVIEW 5

[10] Winbow, G. A., "Compressional and Shear Arrivals in a Multiple Sonic Log," Geophysics, Vol.

50, 1985, pp. 119-126.

[11] Chen, S. T., "Shear-Wave Logging with Dipole Sources," Geophysics, Vol. 53, No. 5, 1988,

pp. 659-667.

[12] Keys, S. W., Borehole Geophysics Applied to Ground-Water Investigations, National Water Well

Association, Dublin, OH, 1990.

[13] Hearst, J. R. and Nelson, P. M., Well Logging for Physical Properties, McGraw-Hill, New York,

1985.

[14] Keys, S. W., "Analysis of Geophysical Logs of Water Wells with a Microcomputer," Ground

Water, Vol. 24, No. 3, 1986, pp. 750-760.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-10-2048.jpg)

![18 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

and radar tomography, were conducted to obtain information on the physical properties

and distribution of the fracture zones. These methods were adequate to obtain information

about rock quality.

This paper describes the features of geotomography, presents results of the investigation,

and indicates the applicability of geotomography to rock investigations.

Features of Geotomography

Geotomography has attracted a great deal of attention as a method of investigating in

detail the distribution of underground physical properties [1]. Geotomography reconstructs

images of underground structures using a large data set. For this reason, geotomography

provides more information than surface geophysical survey methods. The three specific

advantages of geotomography over conventional surface surveys are: (1) the target area is

illuminated from several different angles, (2) the application of source transducers at points

in boreholes near the target allow for increased spatial resolution, and (3) the application

of sources in boreholes means that measurements are not degraded by propagation through

the shallow, extensively weathered zone.

Three kinds of geotomographic methods were used: (1) seismic tomography, (2) resistivity

tomography, and (3) radar tomography. The seismic wave velocity, the resistivity, or the

electromagnetic wave velocity are influenced by physical (rock) properties such as hardness,

condition of cracks, water content, or clay content. Because the response obtained by one

method may not be adequate to characterize all physical properties, it is effective to combine

different geotomographic methods to obtain a good image of the ground structure.

Characteristics of each geotomographic method are as follows.

Seismic Tornography

Seismic tomography reconstructs the seismic wave velocity distribution in the ground.

Seismic wave velocity varies according to rock type, degree of weathering, degree of meta-

morphism, number of cracks, and so forth. In this survey, the fracture zones are expected

to have lower seismic velocities than unfractured rock.

Resistivity Tomography

Resistivity tomography obtains the distribution of resistivity in the ground. Resistivity in

the ground changes according to rock type, mineral content, porosity, degree of saturation,

and the resistivity of water contained in the rock. In this survey, faults or fracture zones

are expected to have lower resistivity values than unfractured rock.

Radar Tomography

Radar tomography obtains the distribution of the propagation velocity of electromagnetic

waves in the ground. The propagation velocity of electromagnetic waves changes mainly

according to the water content of the rock. In this survey, the fracture zones are expected

to have lower velocities than unfractured rock.

Field Measurements and Results

Borehole Arrangernent

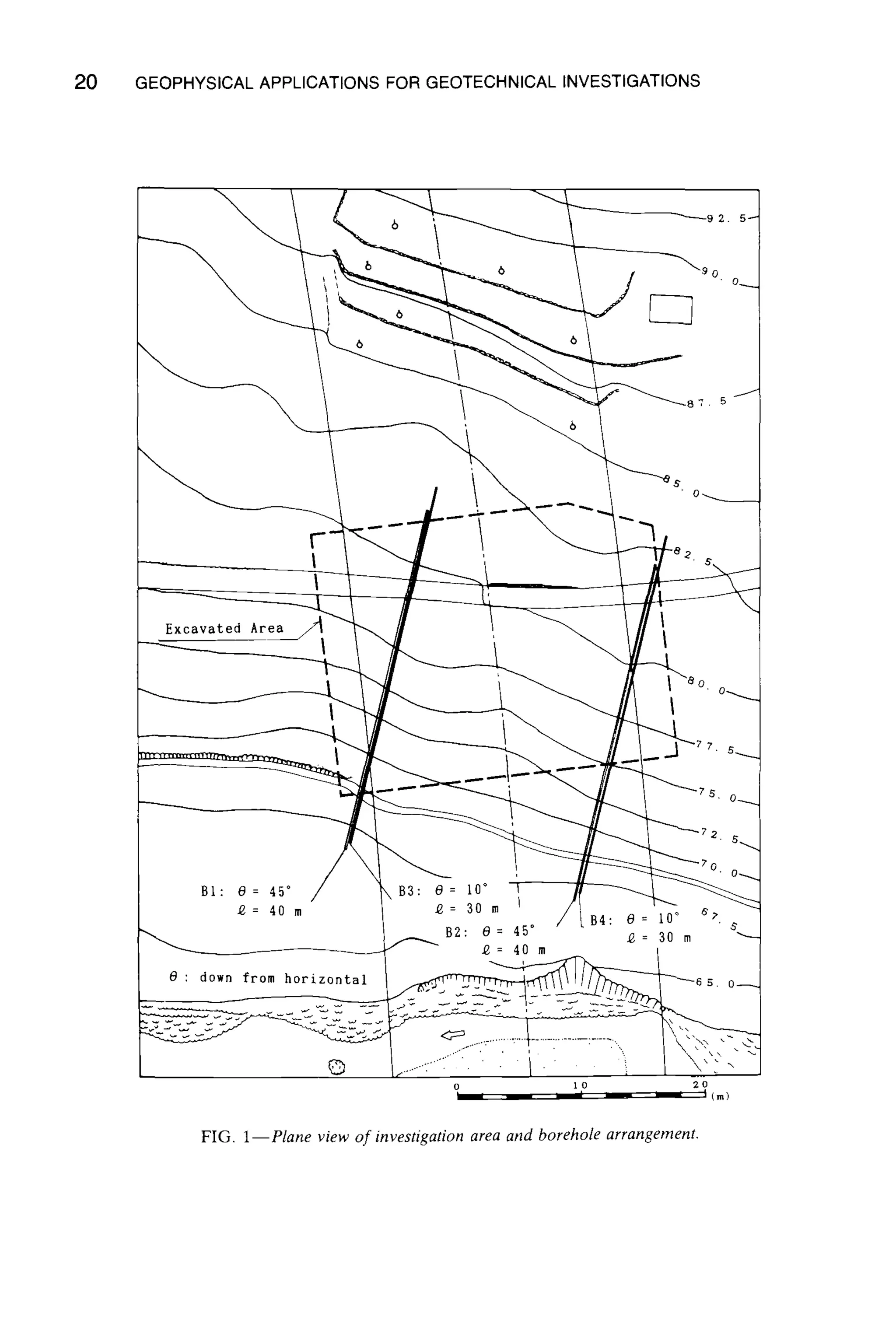

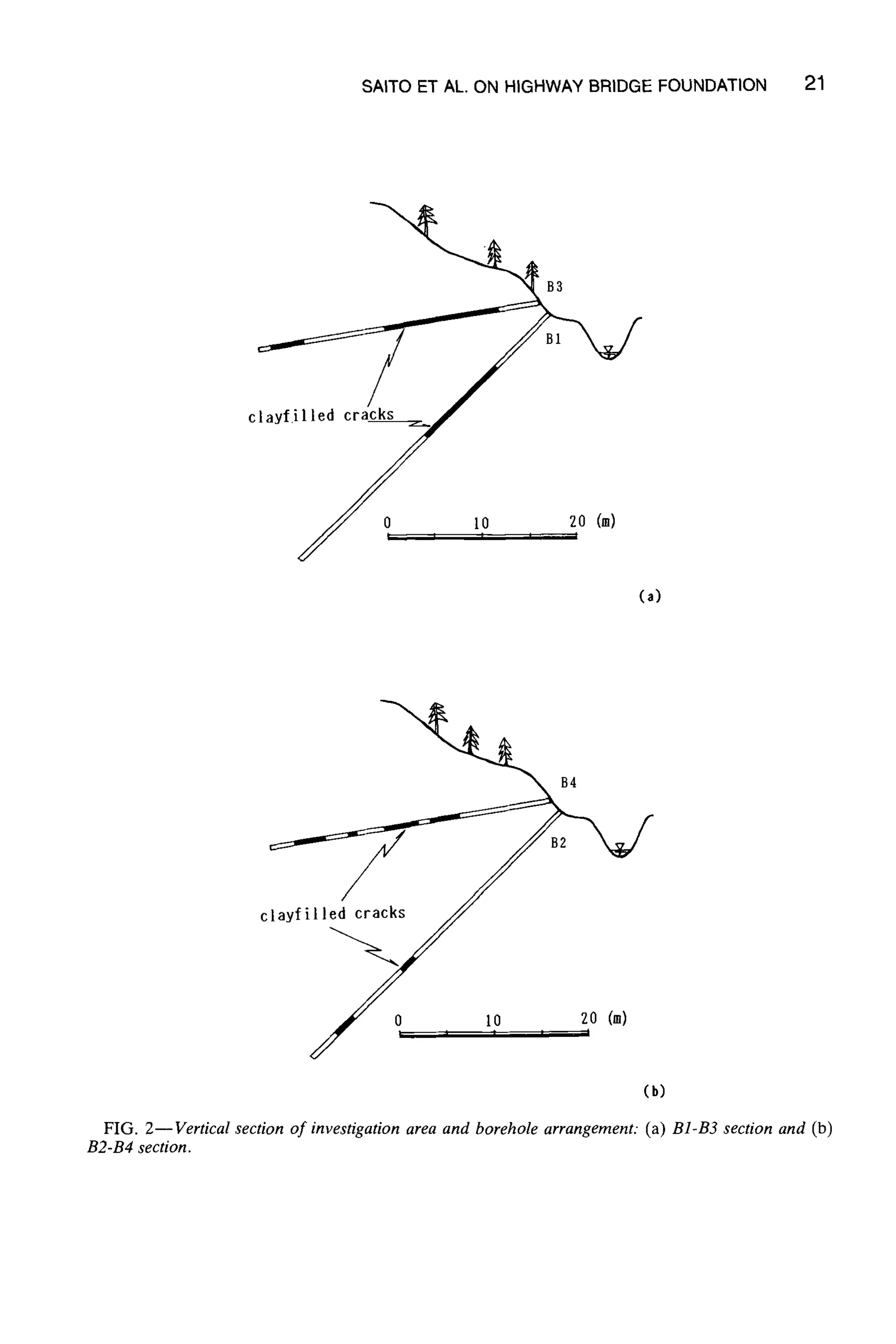

The previous geological survey indicated that the dip angle of the fracture zone was almost

vertical. When the predominant direction of the geological structure is nearly vertical,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-21-2048.jpg)

![SAITO ET AL. ON HIGHWAY BRIDGEFOUNDATION 19

tomography using only vertical boreholes cannot provide a good reconstruction image [2].

Therefore, four boreholes were drilled as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Boreholes B1 and B2

were drilled at 45~ down from the horizontal and were 40 m long. Boreholes B3 and B4

were drilled at 10~ and were 30 m long.

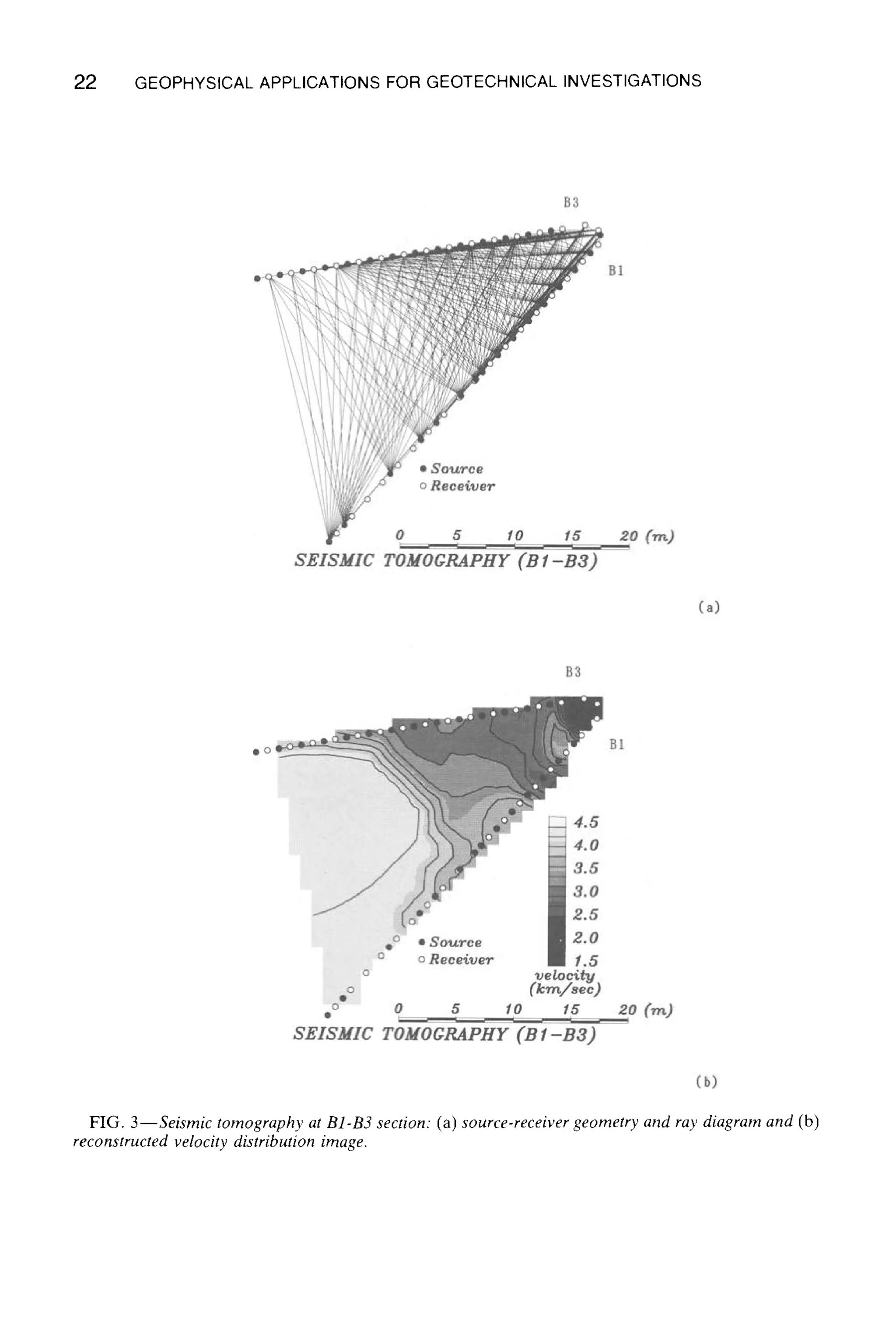

Seismic Tomography

The measurements for seismic tomography were conducted by surrounding the objective

section with source points and receiver points placed in boreholes and on the ground surface

between boreholes. Both source and receiver intervals were 2 m. About 50 g of dynamite

was used as the seismic source. Three sets of twelve-channel borehole geophones and eleven

geophones on the ground surface were used for measurements. A forty-eight-channel digital

data acquisition system (OYO's McSEIS 1600 System) was used.

The objective area was divided into a number of rectangular cells, and the velocity value

for each cell was obtained by an iterative method. In the iterative method, the velocity

(value) for each cell was corrected to minimize the root mean squares of residuals between

calculated and observed travel times. To prevent the divergence of the correction values,

the damped least squares technique was used [3]. The damping parameters were determined

by taking account of the number and directionality of seismic rays passing through each

cell [4].

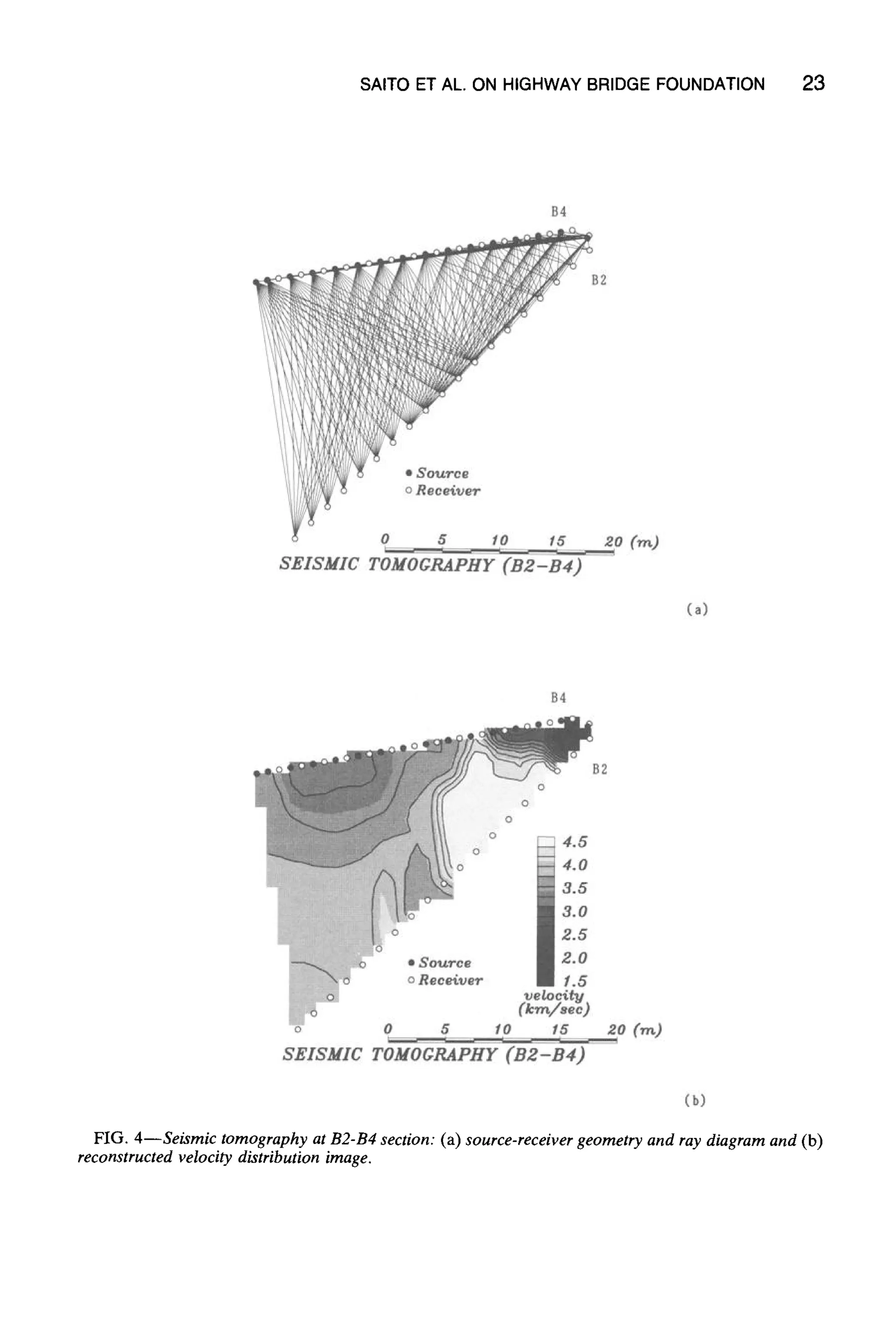

The measurements were conducted at two vertical sections (B1-B3 and B2-B4), a 10~

section (B3-B4), and a 45~section (B1-B2). The results for the two vertical sections and the

10~ section are compared with the results of another tomographic techniques. Figures 3

through 5 show source-receiver geometries, ray diagrams, and reconstructed velocity dis-

tribution images for each section.

B1-B3 Section (Fig. 3)--The P-wave velocity distribution of the B1-B3 section is shown

in Fig. 3b. Velocity values are indicated by shades of gray. Low velocity zones occur closer

to the surface-and between 8 to 19 m in Section B1 and 5 to 22 m in Section B3.

B2-B4 Section (Fig. 4)--Low velocity zones are found near the tops of the boreholes and

around the center of the area vertically. Between these low velocity zones, there is an

extremely high velocity zone.

B3-B4 Section (Fig. 5)--Nearly half of this section is a low velocity area with a velocity

of 2.5 km/s or lower.

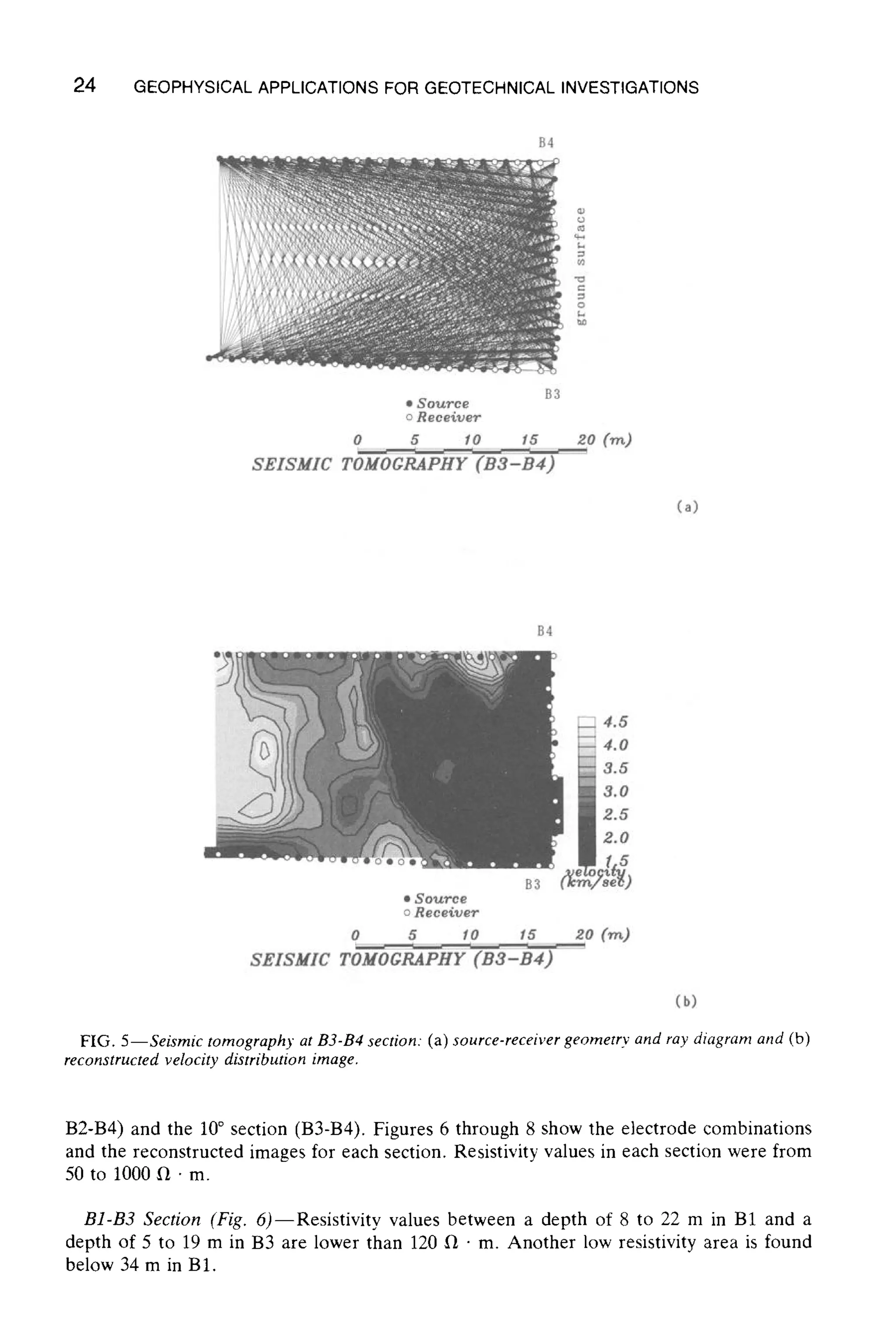

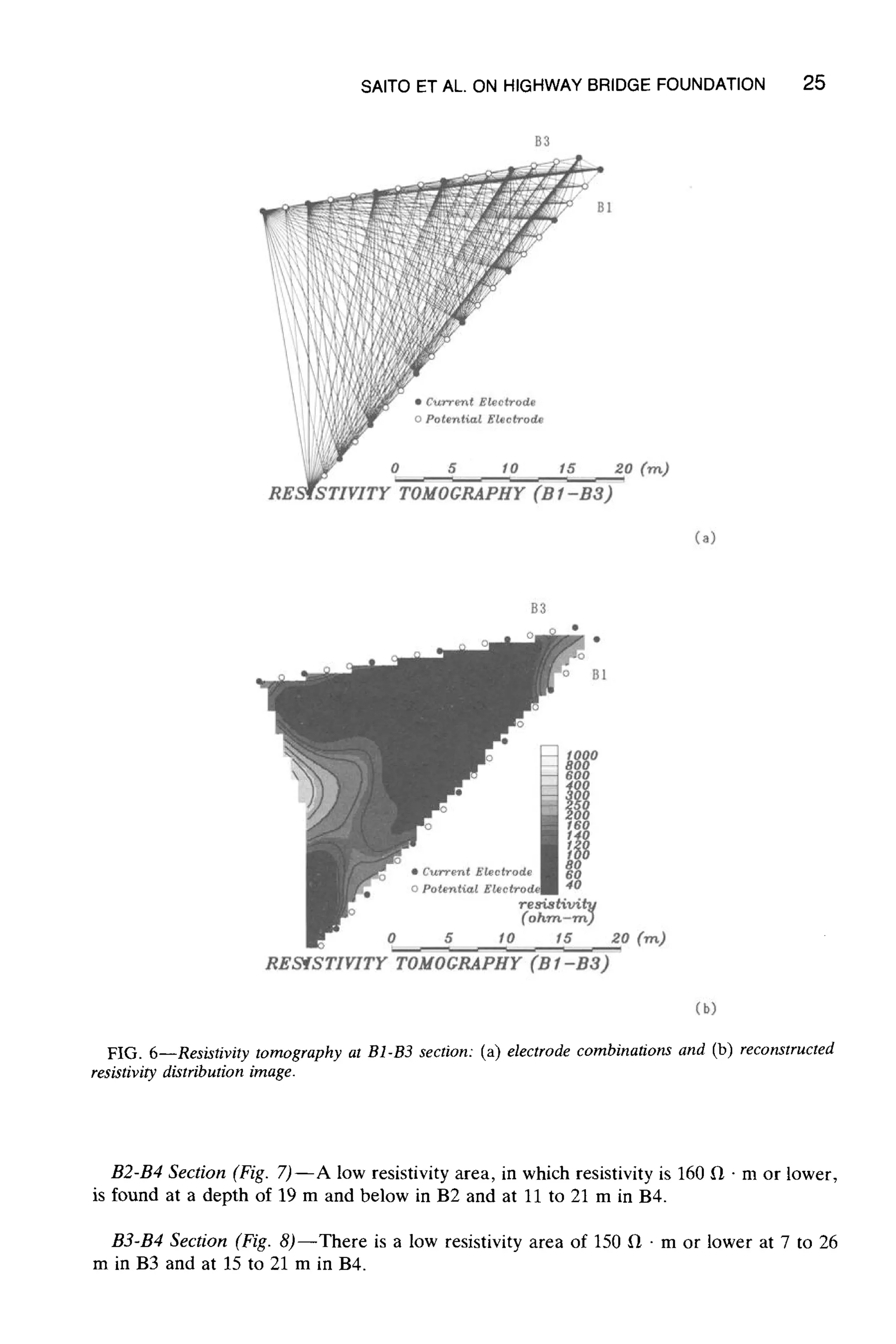

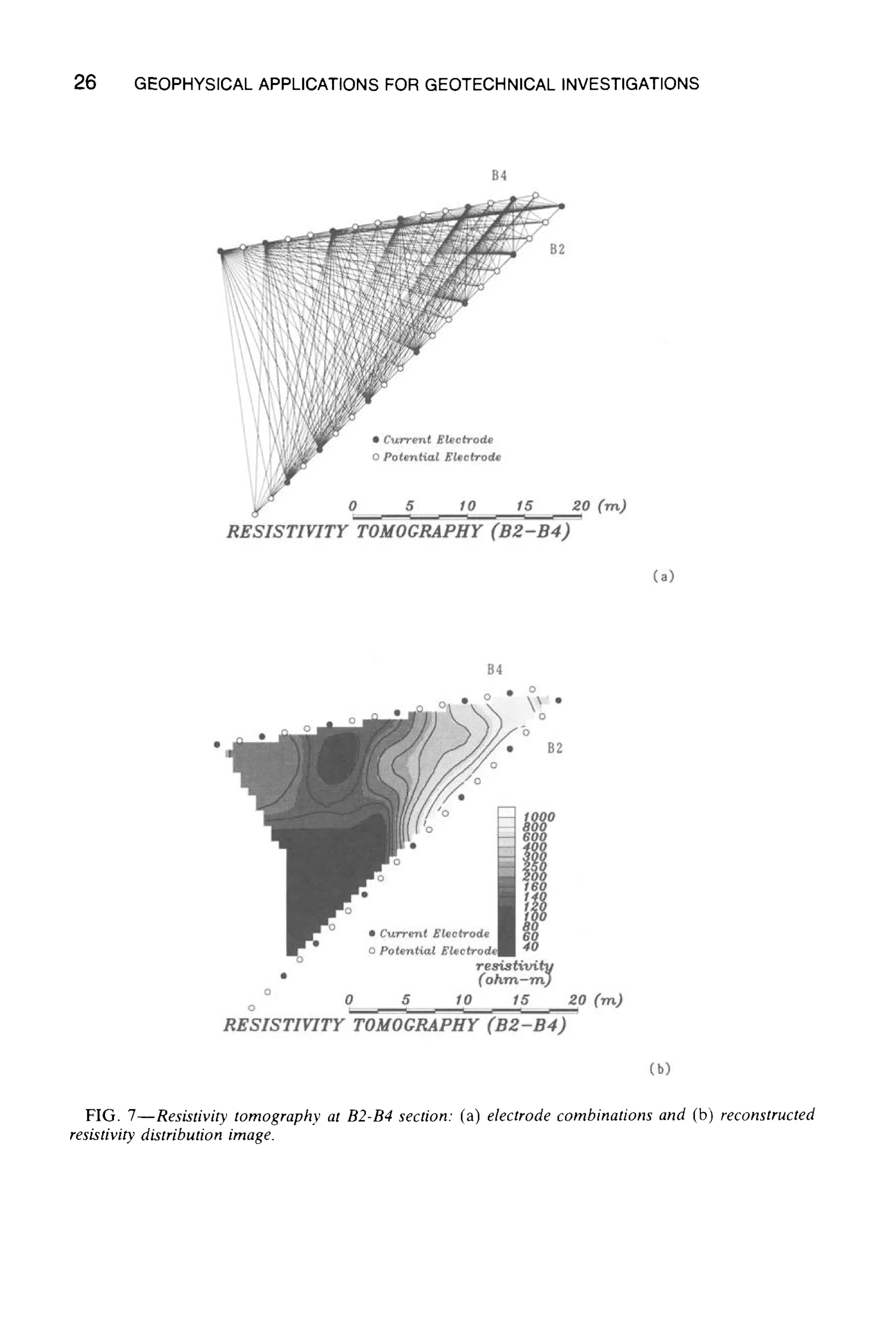

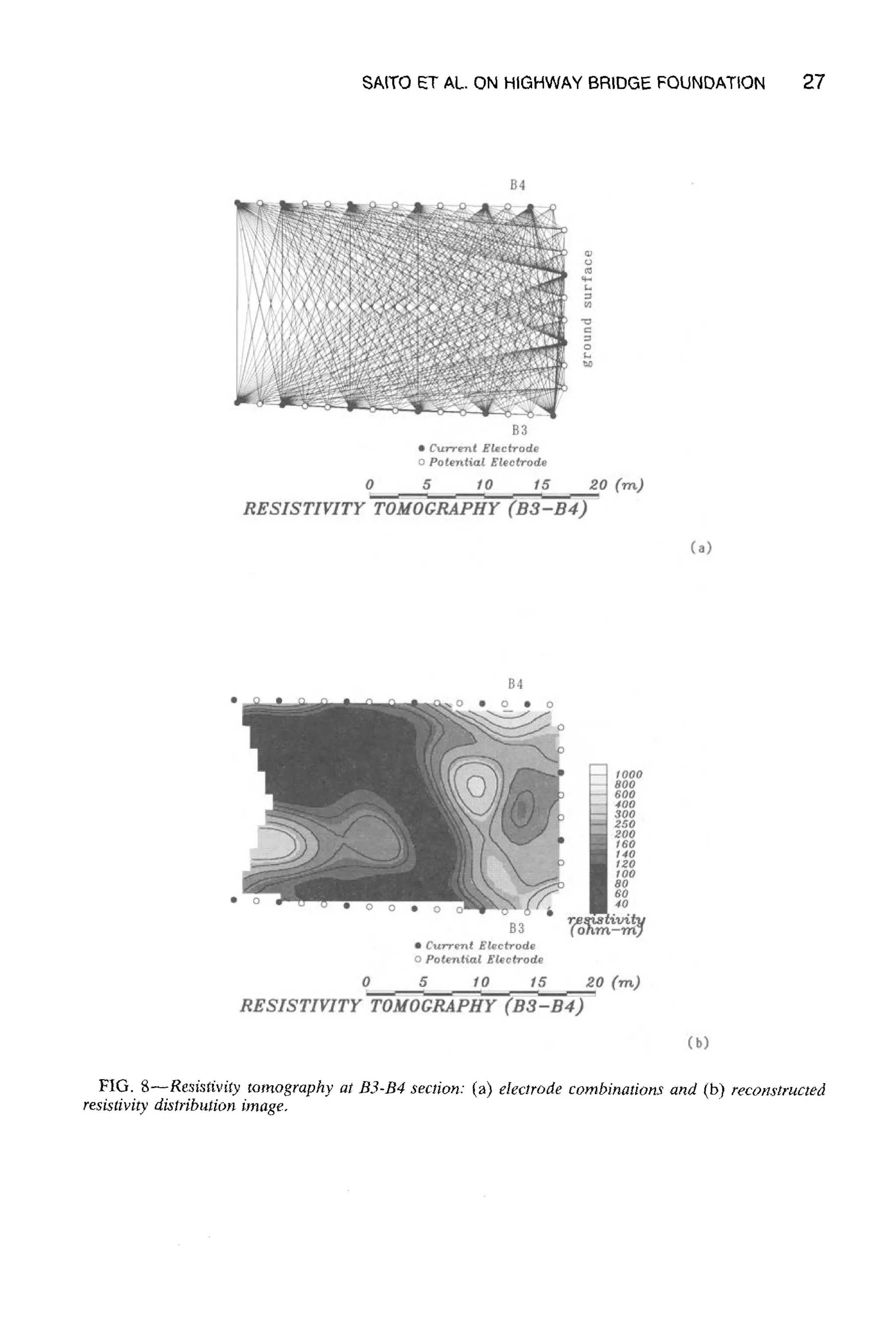

Resistivity Tomography

Resistivity tomography is a two-dimensional resistivity exploration method having higher

resolution than the conventional resistivity exploration method [5].

Electrodes were placed at 2-m intervals in the borehol.es and on the ground surface between

boreholes surrounding the objective area. Electric potential was measured by the pole-pole

array method using OYO's McOHM resistivity meter.

Analysis was conducted by a combination of the alpha centers method and the nonlinear

least squares method [5]. The electric potential at each potential electrode was theoretically

calculated by the alpha centers method. The resistivity distribution was corrected to minimize

the root mean squares of the residuals between calculated and observed electric potentials

by the nonlinear least squares method.

The objective sections for resistivity tomography were two vertical sections (B1-B3 and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-22-2048.jpg)

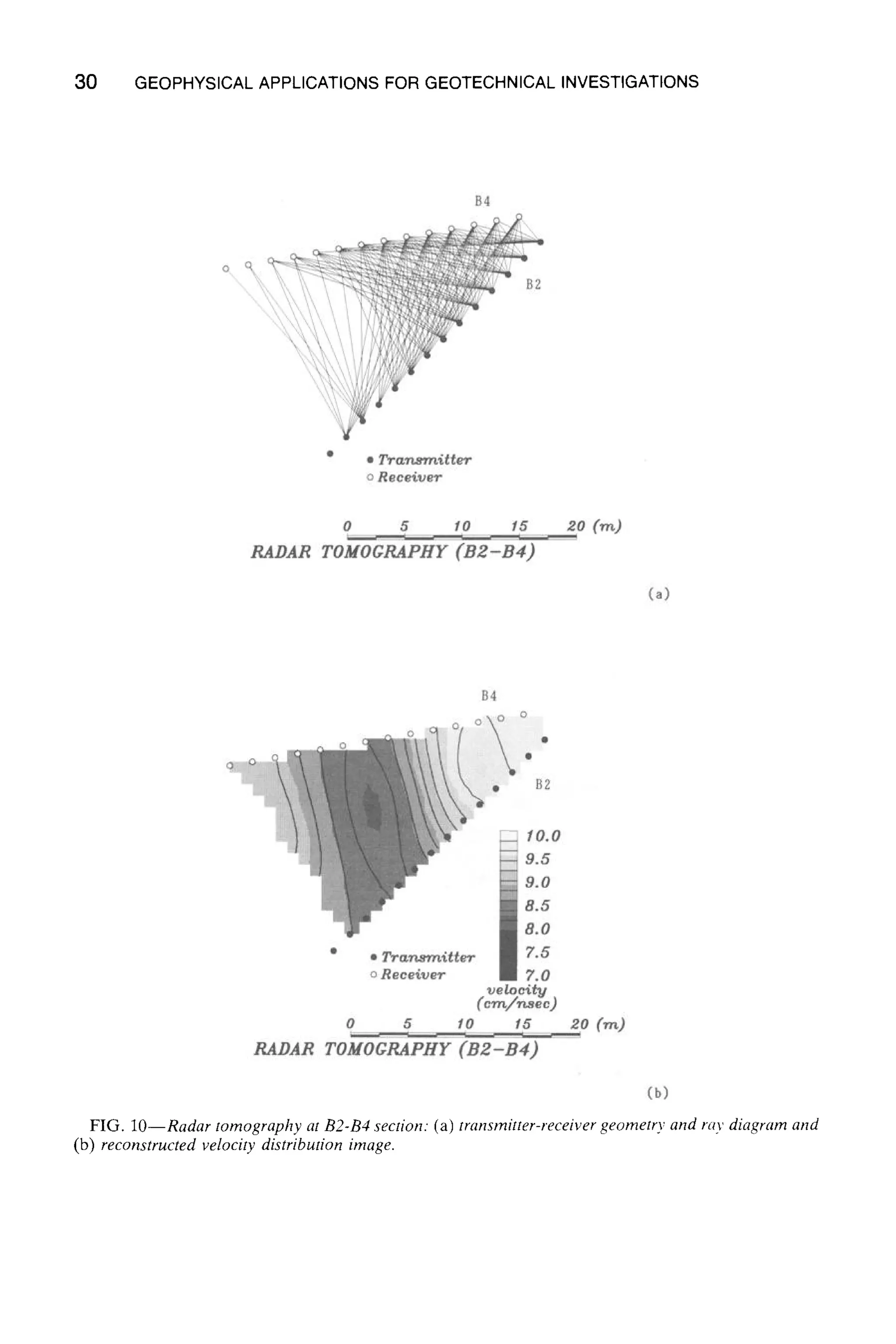

![28 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

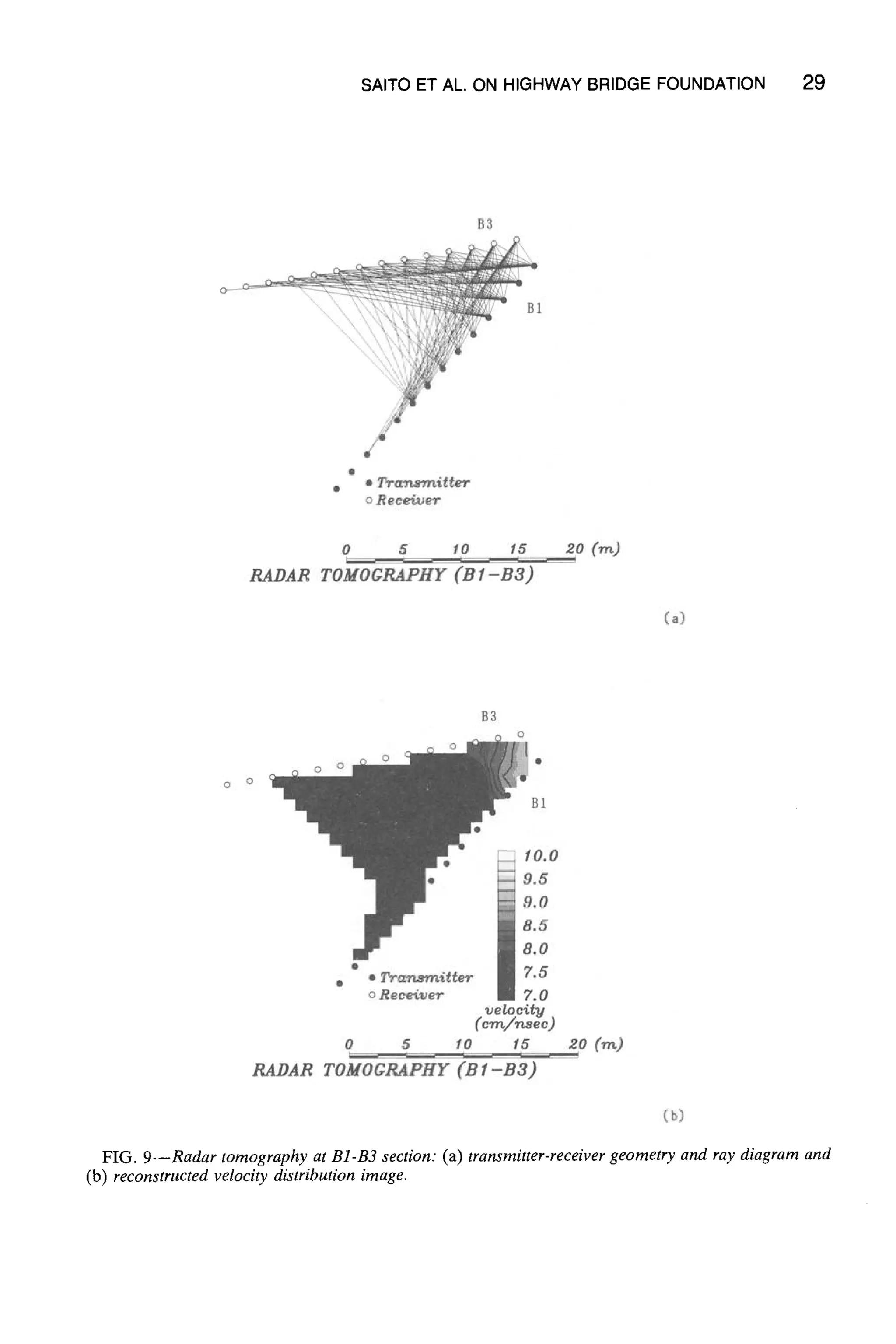

Radar Tomography

In radar tomography, electromagnetic pulse waves are transmitted from one antenna

located in a borehole to a receiving antenna in another borehole. Each antenna was moved

at 2-m intervals. The measurement system used was OYO's YL-R2 Georadar system. The

borehole antennas were especially constructed for experimental use. The center frequency

of the antennas was about 100 MHz and transmitted power was 50 W [6]. The same analysis

procedure as that used in seismic tomography was used in radar tomography.

Attenuation of electromagnetic waves at this site was so high that significant signals could

not be received in horizontal sections. Therefore. the measurements were conducted only

at two vertical sections. Figures 9 and 10 show the transmitting and receiving points, ray

diagrams, and the electromagnetic wave velocity distribution.

B1-B3 Section (Fig. 9)--Electromagnetic wave velocity is relatively lower than the velocity

values in the B2-B4 section. It is estimated, therefore, that water content in the bedrock at

the B1-B3 section is rather high. The area at the depth of 7 m or below has low velocity

and is estimated to be a fracture zone having high water content.

B2-B4 Section (Fig. lO)--The zone, below 16 m in B2 and from 13 to 21 m in B4, is a

low velocity zone that continues vertically and is considered to be bedrock having high water

content.

Consideration

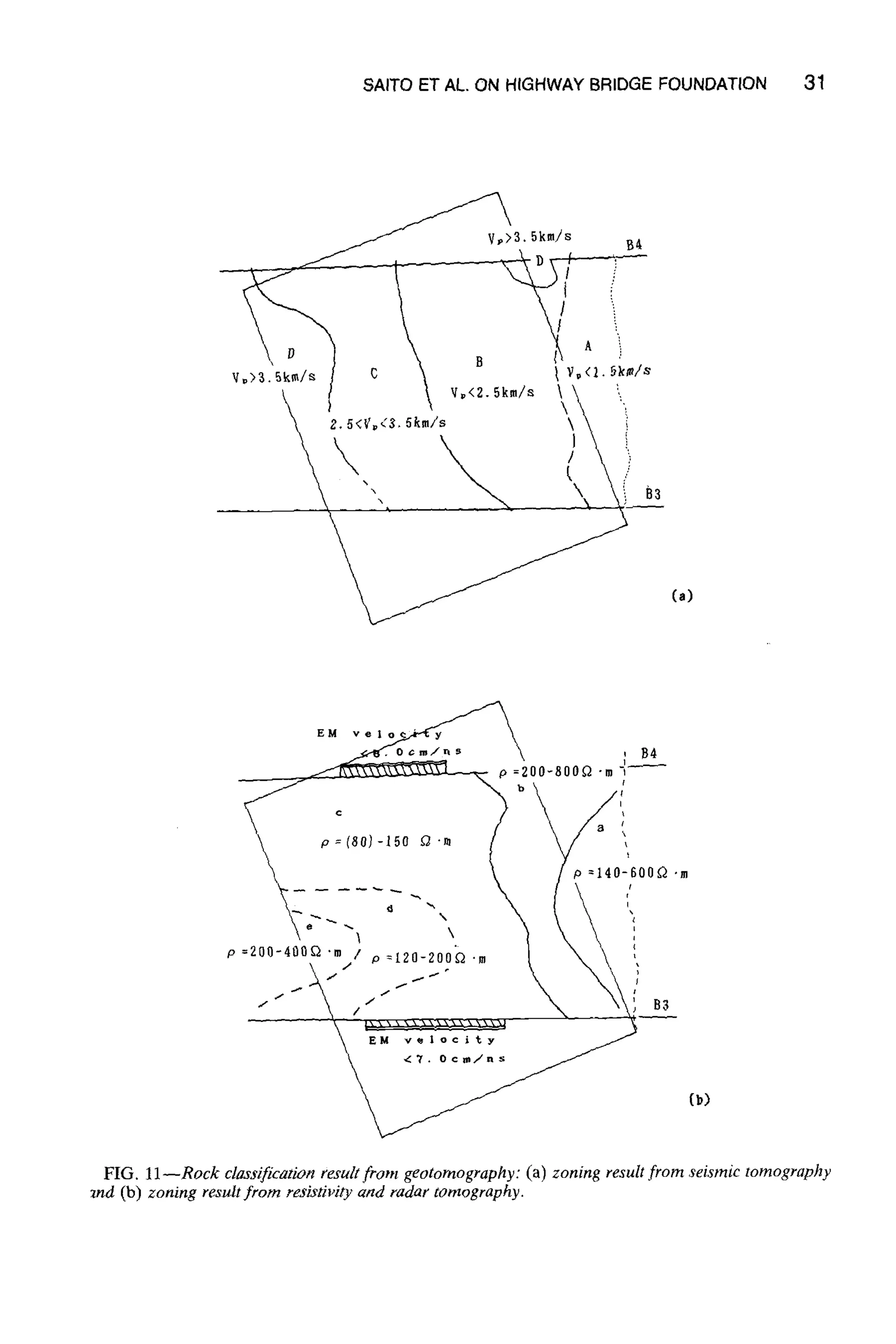

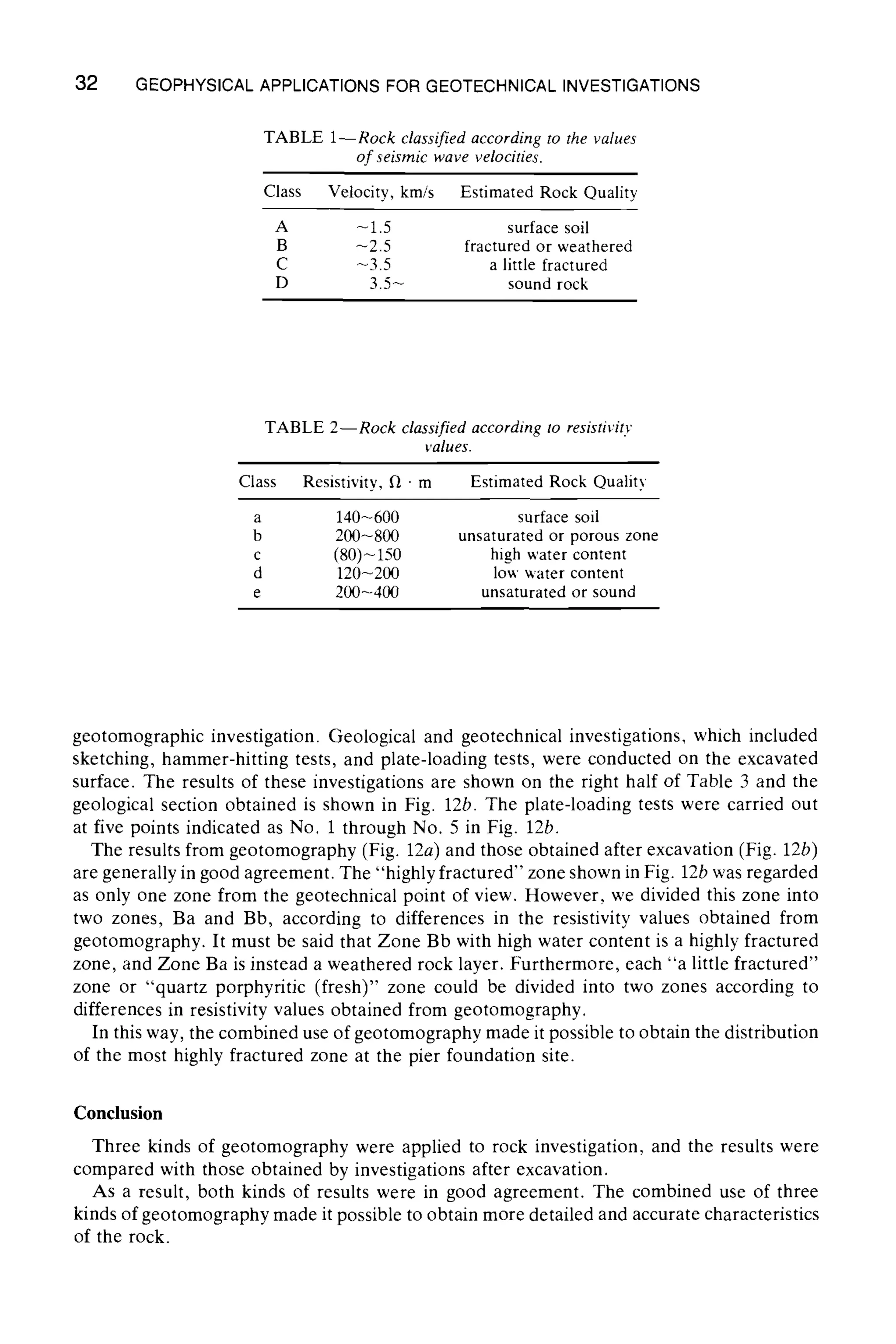

Based on the results of geotomography, we conducted an analysis of rock quality in the

B3-B4 section. We tried to classify the rock according to the values of seismic wave velocities

as shown in Fig. 11a and Table 1.

Since the seismic wave velocity is closely related to the mechanical strength of rock, it

can be said that this figure shows the distribution of mechanical properties of rock.

In this investigation site, the relative variation of resistivity depends mainly on water

content and the quantity of clay that was formed through alteration or fracturing. We tried

to classify the rock according to resistivity values, as shown in Fig. llb and Table 2.

Next, we tried to analyze the rock quality by using the results of seismic tomography

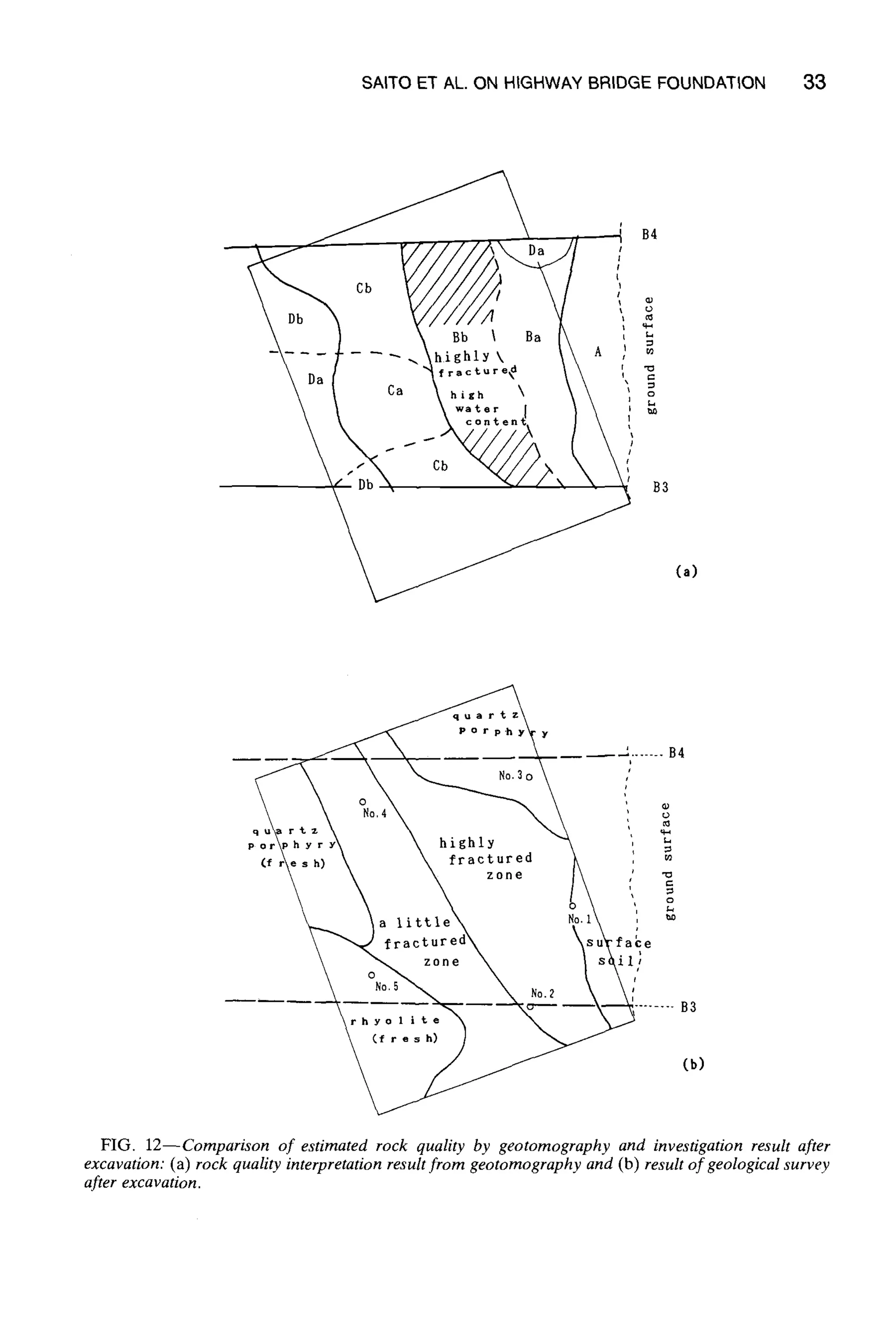

along with the results of resistivity tomography. The final analysis result of tomographic

investigations is shown in Fig. 12a.

Zone A was considered to be the surface soil layer having low seismic wave velocity and

high resistivity. Zones B, C, and D were each divided into two areas of high resistivity or

low resistivity. Zone Ba was considered to be weathered but unsaturated rock distributed

near the surface which had low seismic wave velocity and relatively high resistivity. Zone

Bb was considered to be a highly fractured zone of high water content which had low seismic

wave velocity and low resistivity. Both Zones Ca and Cb were considered to be a little

fractured, but the water content differed from each other. Zone Ca was considered to have

rather low water content which had rather low seismic wave velocity and a little low resistivity.

Zone Cb was considered to have high water content which had rather low seismic wave

velocity and low resistivity. Both Zones Da and Db were relatively fresh and sound rock,

however, Zone Db had rather high water content.

Consequently, it can be said that Zones Bb, Ca, and Cb correspond to fracture zones.

In particular, Zone Bb is considered to correspond to the most highly fractured zone having

high water content. The results mentioned above are shown in the left half of Table 3.

Excavation for the construction of the bridge pier foundation was carried out after the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-31-2048.jpg)

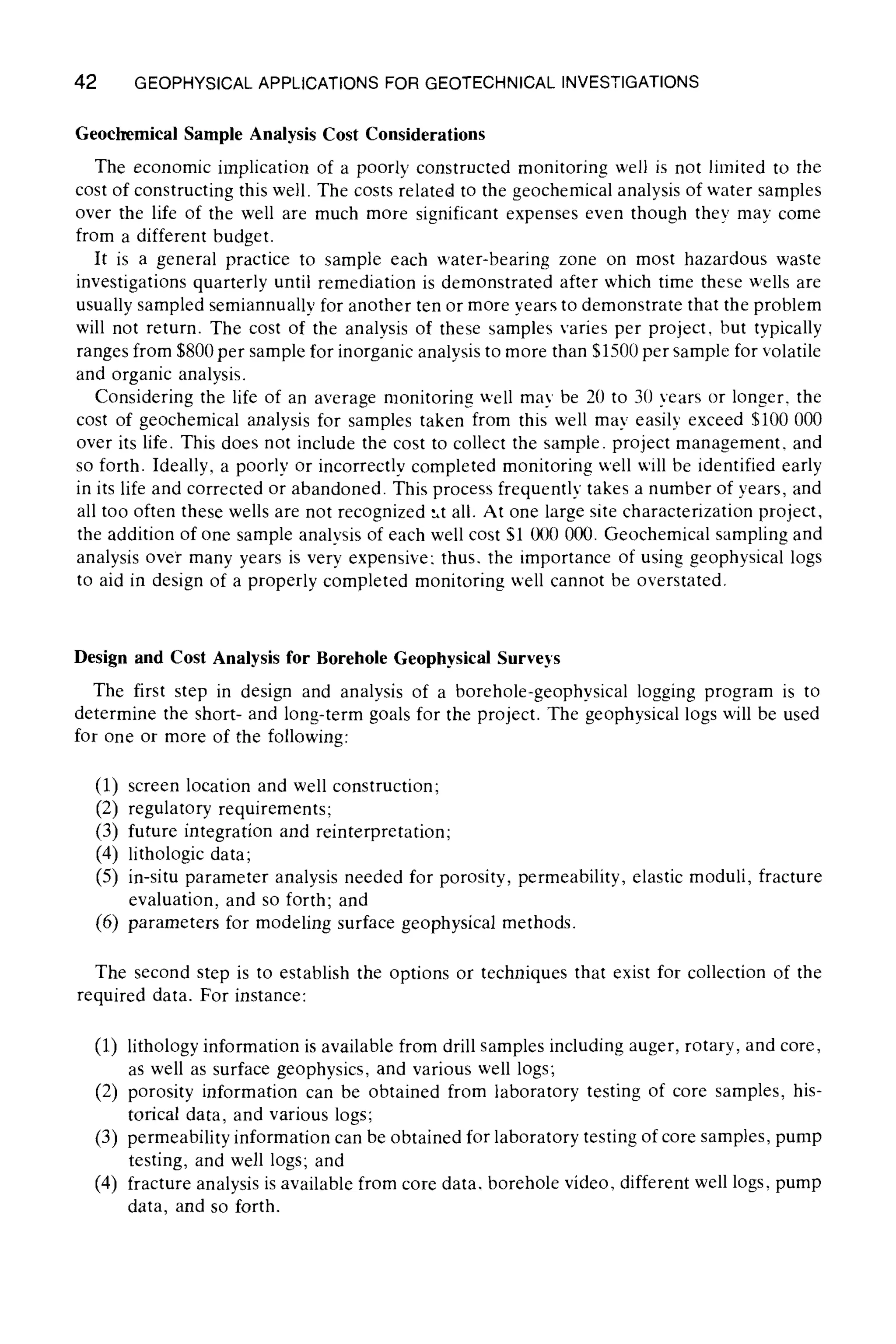

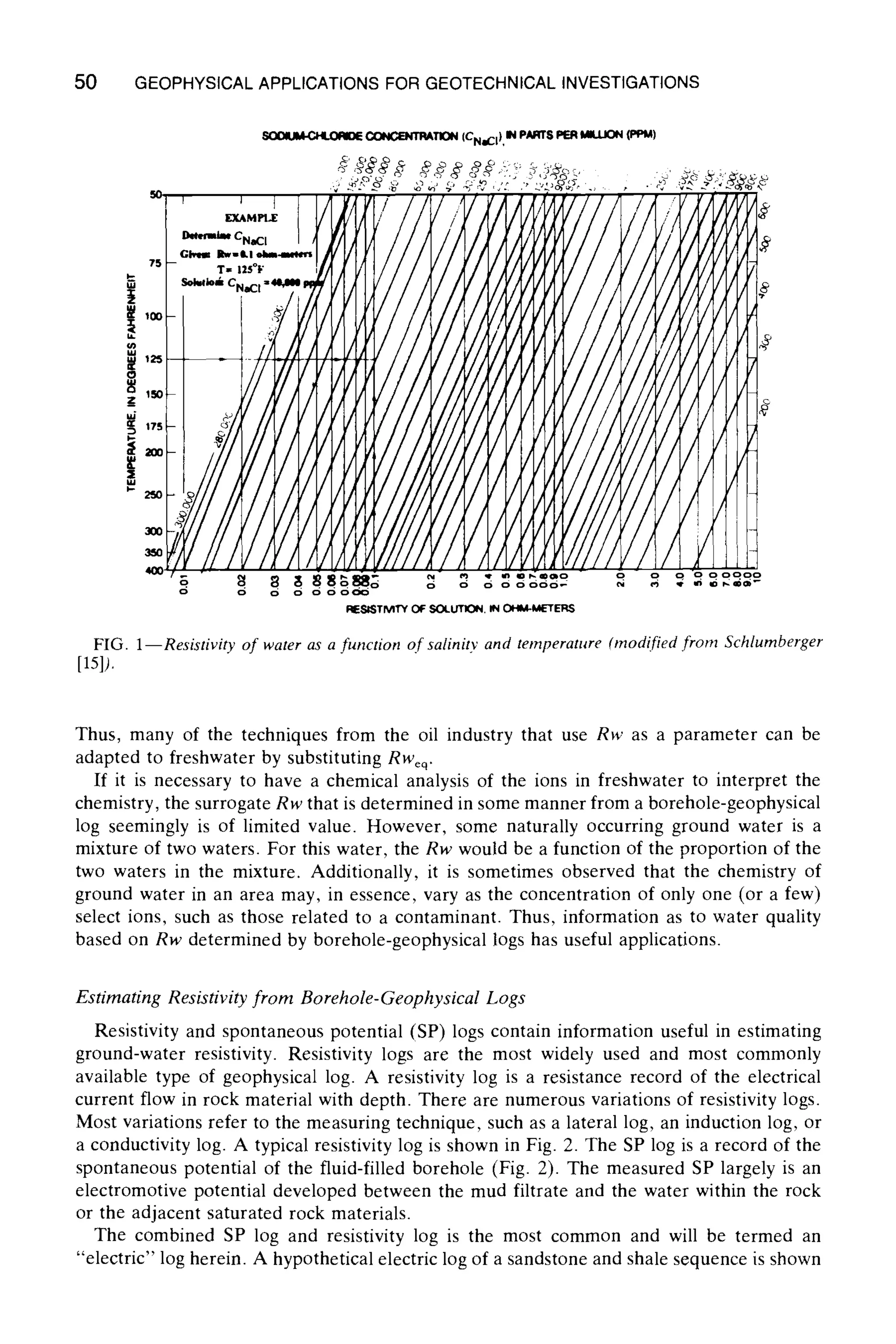

![34 GEOPHYSICAL APPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

TABLE 3--Results from geotomography and investigationsafter excavation

Results from Geotomography

Results from Investigations after

Excavation

Seismic Deformation

Velocity, Resistivity, Estimated Constant,

Class km/s ~ 9m Quality Quality kgf/cmz

A -1.5 140-600 surface soil surface soil

weathered

Ba 200-800 (unsaturated)

-2.5 highly fractured

highly fractured

Bb 80-150 and high

water content

a little fractured

and rather

Ca 120~200

low water

content

-3.5 a little fractured

a little fractured

Cb 80-150 and high

water content

290

(No. 1 point)

160

(No. 2 point)

650

(No. 4 point)

quartz porphyry 1900

Da 200-400 sound or fresh (fresh) (No. 3 point)

3.5-

sound and rhyolite (fresh)

Db 80-150 rather high 840

water content (No. 5 point)

In the future, we intend to apply geotomography to many other sites having various

geological conditions and to conduct further studies on the applicability of geotomography

for civil engineering purposes.

References

[1] Sassa, K., "Suggested Methods for Seismic Testing Within and Between Boreholes,'" International

Journal of Rock Mechanic Sciences and Geomechanics Abstracts, Vol. 25, No. 6, 1988, pp. 447-

472.

[2] Sakayama, T., Ohtomo, H., Saito, H., and Shima. H., "Applicability and Some Problems Of

Geophysical Tomography Techniques in Estimation of Underground Structure and Physical Prop-

erties of Rock," presented at the 2nd International Symposium on Field Measurements in Geo-

mechanics, Kobe, Japan, April 1987.

[3] Aki, K. and Lee, W. H. K., "Determination of Three-Dimensional Velocity Anomalies Under a

Seismic Array Using First P Arrival Times from Local Earthquakes," Journal of Geophysical

Research, Vol. 81, 1976, pp. 4381-4399.

[4] Saito, H. and Ohtomo, H., "Seismic Ray Tomography Using the Method of Damped Least Squares,"

Exploration Geophysics. Vol. 19, Nos. 1/2, 1988. pp. 348-351.

[5} Shima, H. and Sakayama, T., "Resistivity Tomography: An Approach to 2-D Resistivity Inverse

Problems," presented at the 57th SEG Annual International Meeting, New Orleans, Oct. 1987.

[6] Toshioka, T. and Sakayama, T., "Preliminary Description of Borehole Radar and First Results,"

presented at the 76th SEGJ Conference, Tokyo, Japan, April 1987.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-37-2048.jpg)

![Robert E. Crowder, 1 Larry A. Irons, 2 and Elliot N. Yearsley ~

Economic Considerations of Borehole

Geophysics for Hazardous Waste Projects

REFERENCE: Crowder, R. E., Irons, L. A., and Yearsley, E. N., "Economic Considerations

of Borehole Geophysics for Hazardous Waste Projects," Geophysical Applications for Geo-

technical Investigations, ASTM STP 1101, Frederick L. Paillet and Wayne R. Saunders, Eds.,

American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, 1990, pp. 37-46.

ABSTRACT: In environmental or hazardous waste investigations, simple homogenous sub-

surface geologic conditions have historically been assumed. In reality, heterogeneous condi-

tions predominate. The costs of remediation and the consequences of incorrect remediation

are increasing rapidly. These investigations often require the collection of extensive amounts

of data to evaluate the problems sufficientlyto recommend and execute appropriate remedial

action.

Borehole geophysics can be used to obtain valuable data including information on geologic

conditions and in-situ physical parameters in drill holes. The amount and benefit of this

information is determined by the logging suite, borehole conditions, geologic parameters,

interpreter experience, and application of current technology.

Typical costs for drilling and geophysical logging associated with different types of environ-

mental investigations vary considerably. These costs are a function of the types and quantity

of the desired data, whether the geophysical logging and analysis will be performed in-house

or by an outside consultant, and the operational field environment.

Five case histories demonstrate the application of borehole geophysics to hazardous waste

investigations and provide qualitative evidence as to its cost-effectiveness. The primary con-

clusionsindicated by these case histories are that: (1) geophysical logs assist in well construction

efforts; (2) borehole geophysical logs provide in-situphysical measurements not available from

other methods; and (3) costs associated with borehole loggingcan be justified by consideration

of the total cost of drilling, completion, and monitoring and the implications of inadequate

understanding of the subsurface in a remediation program.

KEY WORDS: borehole geophysics, monitor well, cost, hazardous waste site investigations

In environmental investigations for ground-water contamination problems, simple, ho-

mogenous subsurface geologic conditions have historically been assumed. These site char-

acterizations are proving to be more difficult than originally anticipated, and a number of

prior investigations appear to be flawed. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

study [1] of 22 Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) sites showed problems

including:

(1) incorrect screening in 50% of the monitoring wells,

(2) incorrect placement of 30% of the wells, and

(3) on 10% of the sites, Wells were placed before determining the direction of ground-

water flow.

1President and geological engineer, respectively, Colog, Inc., 10198th St., Golden, CO 80401.

2Senior associate geophysicist, Ebasco/Envirosphere Co., 143 Union Blvd,, Suite 1010, Lakewood,

CO 80228.

37

Copyright91990by ASTM International www.astm.org](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-39-2048.jpg)

![38 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

The geologic conditions encountered on most of these sites are complex and often require

collecting extensive amounts of data to evaluate the problems sufficiently to recommend

and execute the appropriate remedial action. The costs of remediation and the consequences

of incorrect remediation are increasing rapidly [2]. Each project is unique in certain respects

because the particular environment, potential contaminant, and goals will all be somewhat

different.

The purpose of this paper is to convey experience and information regarding the economic

considerations involved in obtaining subsurface data relevant to hazardous waste investi-

gations. Discussions contained herein outline the benefits of the application of borehole

geophysics to the problem of subsurface interpretation. These discussions provide guidelines

and considerations for geophysical logging operations and costs and review historical prac-

tices and costs of drilling, coring, testing, and geochemical analyses.

The common thread in these topics is their application toward the investigation and

characterization of hazardous (or potentially hazardous) waste sites. The relative cost-

effectiveness of borehole geophysics in these efforts is addressed. The thesis of this paper

is that borehole geophysics provides a cost-effective means for the subsurface investigations

of these sites. Furthermore, that the existential measurements provided by borehole geo-

physics complement core data, support surface geophysics, and offer geologic and hydro-

geologic information not otherwise available.

Borehole Geophysical Logging Considerations and Benefits

There is no uniform logging suite applicable to every project, and no unambiguous rules

for log interpretation exist. Most log analyses in ground-water investigations are based upon

techniques developed by the petroleum industry. These techniques may not be directly

applicable when applied to shallow ground-water investigations, and less experience and

scientific literature is available in this area. Many ground-water engineers and geologists

have no formal training in the use of borehole geophysics, whereas their counterparts in

the petroleum industry are well trained in the use of these logs.

Furthermore, logging tools developed for the petroleum industry are inadequate for the

shallow depth and small-diameter applications encountered in most environmental inves-

tigations. Many monitoring wells are drilled and completed with hollow-stem auger tech-

niques in the vadose zone. Logging in the vadose or unsaturated zone is feasible and provides

valuable information not available elsewhere, but disturbances to the formation from drilling

in this zone may produce large changes on the logs. Quantitative analysis usually requires

information from several types of logs. Sometimes the drill holes are not stable enough for

open-hole logging or to allow more than one open hole pass by a geophysical probe, and

the selection of probes for the initial pass requires careful consideration. Radioactive sources

required for some measurements are regulated, and the use of these sources may not be

feasible to use on some projects.

Many environmental projects are located in areas distant with respect to the historical

petroleum and mineral industry service companies, often requiring expensive mobilization.

Environmental projects frequently have a low production rate for drilling.new wells, both

in number and depth. The time lapse between wells may be several days. These factors

increase the logging costs. Health and safety training requirements can be a major burden

for many of the smaller slimhole logging contractors and may prevent them from entering

the environmental market.

Historically, only a few simple logs have been used in nonpetroleum applications. Many

people expect slimhole nonpetroleum logs for environmental applications to be inexpensive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-40-2048.jpg)

![CROWDER ET AL. ON BOREHOLE GEOPHYSICS

TABLE 1--Direct benefits of borehole geophysics.

39

Broad Category Specific Aspects

Well construction

Physical properties

Stratigraphic

correlation

depth and identification of lithologicbeds, borehole size and volume,

water table

porosity, density, resistivity, temperature, fluid flow, water quality,

fracture identification, rock strength parameters

continuity of aquifers and confining beds based on cross-hole

correlation, facies changes

and accordingly do not budget for the necessary logs and interpretation. Many firms do not

have staff expertise to use much of the advanced geophysical information. For example,

knowledge may be limited to recognition of apparent sand-shale zones for screen selection

and may not include proper interpretation of the remaining data. The economics of running

a complex suite that cannot be properly used would appear questionable.

In spite of the above perceptions and hindrances to slimhole logging, borehole geophysics

has important benefits in hazardous waste investigations when interpreted properly [3].

These benefits can be classified as direct and indirect [4,5], as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Borehole GeophysicalLogging Costs

Traditional logging costs were based upon a low service charge (base time rate), a footage

charge (based upon the types of probes and total project footage logged), and miscellaneous

expenses for such items as per diem and standby. Costs per foot were kept low by logging

high footages in many wells. Typically, the drill rig was not incurring standby charges on

energy/mineral exploration projects and the standby charges for the petroleum applications

were generally well understood by everyone involved with those projects.

The primary cost factor for most environmental logging programs is personnel and equip-

ment time. This time factor includes mobilization/demobilization to and from the project

area, standby waiting for a well to be finished, pre- and post-log calibration, data acquisition,

data processing, interpretation, and decontamination of personnel and equipment. For the

typical shallow wells encountered on most environmental investigations, actual data acqui-

sition time is the least significant aspect. Footage charges are difficult to compare to the

classical slimhole logging industry and tend to be a minor element in the overall cost. The

number and type of logs affect the overall costs in that it takes as long or longer to pre-

and post-calibrate, setup, and decontaminate on a shallow well as it does on a deep well.

However, on many projects, the cost to run one or several extra logs may be insignificant

TABLE 2--Indirect benefits of borehole geophysics.

1. Objective, repeatable data collected over a continuous vertical interval.

2. Digital data is conveniently stored, processed, and transmitted.

3. Log results are available at well site or shortly thereafter.

4. Borehole geophysical data is synergistic with core data, surface geophysics, and other

borehole geophysical data.

5. Borehole logs can be standardized to facilitate correlation between different phases of an

investigation by different firms.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-41-2048.jpg)

![46 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

hole geophysics is a tool that has been underused on many of these projects: however, it

can be cost-effective in site investigation and also in long-term monitoring.

Primary reasons for the lack of use of borehole geophysics include a lack of understanding

of the methods, the availability of the services, the availability of log interpreters/analysts,

and a lack of understanding of the goals of the projects. As these goals become better

defined, the value of more objective log data increases. Education and experience are starting

to overcome some of this lack of understanding, and regulations are now stipulating minimal

geophysical logs on many projects. A better understanding of the limitations of the log data,

especially during acquisition, also aids in evaluating the information effectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper wish to thank Mr. Larry Dearborn with CE Environmental,

Ebasco Services, Inc., and the other engineering companies contacted for the sharing of

cost information used in this paper.

References

[1] Wheatcraft, S. W.. Taylor, K. C., Hess, J. W.. and Morris, T. M., 'Borehole Sensing Methods

for Ground-Water Investigations at Hazardous Waste Sites." Water Resources Center, Desert

Research Institute, University of Nevada System. Cooperative Agreement CR 810t)52 for Envi-

ronmental Monitoring Systems Laboratory, Office of Research and Development. U.S. EPA, Las

Vegas, NV 89114, Dec. 1986. Reproduced bv U.S. Department of Commerce. National Technical

Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161.

[2] Crowder, R. E. and Irons, L., "Economic Considerations of Borehole Geophysics for Engineering

and EnvironmentalProjects," in Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Geophysics

to Engineeringand Environmental Problems. Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO. 1989.

[3] Crowder, R. E., "Cost Effectiveness of Drill Hole Geophysical Logging For Coal Exploration,"

paper presented at the Third InternationalCoal Exploration Symposium,Calgary, Alberta, Canada,

1981.

[4] Keys, S., "Borehole GeophysicsApplied to Ground-WaterInvestigations,'"U.S. Geological Survey,

Open-File Report 87-539, Dec. 1988.

[5] Stegner, R. and Becker, A., "Borehole Geophysical Methodology: Analysis and Comparison of

New TechnologiesFor GroundWater Investigation," in Proceedingsof the Second National Outdoor

Action Conference and Aquifer Restoration, Ground Water Monitoring and Geophysical Methods,

Vol. II, 1988.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-48-2048.jpg)

![Donald G. Jorgensen I

Estimating Water Quality from Geophysical

Logs

REFERENCE: Jorgensen, D. G., "Estimating Water Quality from Geophysical Logs," Geo-

physicalApplicationsfor GeotechnicalInvestigations,ASTM STP 1101, Frederick L. Paillet

and Wayne R. Saunders, Eds., American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia,

1990, pp. 47-64.

ABSTRACT: Borehole-geophysical logs can be used to obtain information on water quality

and water chemistry: Water quality characteristics that normally are measured directly in water-

filled holes or wells include chloride, dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, and conductivity.

In-situ ground water may exist at some distance adjacent to the borehole, and estimates of

water quality or water chemistry can be made by measuring the resistivity or specific electrical

conductivity of the water in pore spaces. Most geophysical logs, however, are made in test

holes filled with drilling fluid. In this environment, logs enabling estimates of water resistivity

(Rw) are useful. Relations among Rw and dissolved solids, sodium chloride solutions, and

temperature are well established for saline waters; for freshwater, however, the activities of

other dissolved ions also need to be considered. The spontaneous potential (SP) is a function

of activity of the mud filtrate and water resistivity and, thus, can be used to estimate Rw.

Two methods of estimating Rw are useful: the spontaneous potential (SP) method, which

uses data from a spontaneous potential log and a resistivity log, and the cross-plot method,

which uses log-derived porosity and resistivity-log data. The application of SP logs depends

upon the water quality contrast between the water in the pores (Rw)and the mud filtrate on

the borehole wall. Both methods estimate Rw to about a half order of magnitude. However,

the accuracy of both methods can be greatly improved if additional data, such as a chemical

analysis, can be correlated to a log.

KEY WORDS: geophysical logging, spontaneous potential, resistivity, ground-water quality

The chemical constituents of water affect the responses of nearly all borehole-geophysical

logs. Thus, borehole-geophysical logs normally contain information on water quality that

can be extracted by using various methods of analysis.

This paper describes how borehole-geophysical logs can be used to estimate water chem-

istry; however, the scope of this paper excludes a description of logging tools, except in a

very general way, and the physics that affect the responses measured by the wireline tool.

Detailed information of various geophysical logs can be obtained from textbooks such as

Log Analysis of Subsurface Geology [1] and WellLogging of Physical Properties [2], industry

manuals such as Log Interpretation Principles/Applications [3] and Log Interpretation

Fundamentals [4], or special texts such as Borehole Geophysics Applied to Ground-Water

Investigations [5]. In general, the problems of quantitatively evaluating clay content or

"shaleyness" from borehole-geophysical logs is beyond the scope of this paper. However,

1Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, P.O. Box 25046, Mail Stop 421, Denver Federal Center,

Denver, CO 80225-0046.

2R. Leonard, written communication, U.S. Geological Survey, 1984.

47

Copyright9 1990by ASTM International www.astm.org](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-49-2048.jpg)

![48 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONSFOR GEOTECHNICALINVESTIGATIONS

qualitative evaluation of clay content generally can be made from the response recorded by

a gamma-ray log.

The techniques presented in this paper greatly rely on relations among temperature,

density, and resistivity to water chemistry properties, such as concentrations of dissolved

solids, sodium chloride, and chloride. These relations are given in the appendices. Material

presented herein relies heavily on the material published in the U.S. Geological Survey

Water Supply Paper 2321, "Some Uses of Geophysical Logs to Estimate Porosity, Water

Resistivity, and Intrinsic Permeability" [6].

Direct measurements of formation water quality or water chemistry can be made only in

water wells, provided the water in the well is the same as that in the adjacent formation.

Thus, a direct-measuring borehole-geophysical probe can measure the variation with the

depth of different water quality or water chemistry properties. However, because of slight

differences in head that exist in any transient ground-water flow system, the well bore causes

a "short circuit" and water flows into the borehole. This flow complicates the interpretation

of direct-measuring geophysical logs made by probes used in the downhole measurements

of chemistry and water quality in a particular geohydrologic zone penetrated by the borehole.

Water chemistry information can be obtained indirectly from borehole-geophysical logs

run in holes filled with drilling fluids. Under these conditions, unaltered or uncontaminated

aquifer water typically is found adjacent to the annulus of the borehole. In addition to

drilling fluid in the borehole, it is likely there is a mud cake or mud filter formed on the

borehole wall. Drilling fluid typically is forced through the mud filter and invades the adjacent

formations for various distances; that is, mud filtrate invades the formation, Thus, water

chemistry cannot be measured directly. To determine water chemistry in the formation (or

aquifer) by using borehole-geophysical logs, it is necessary to differentiate among the effects

of the drilling fluid, mud filter, invading mud filtrate, and the effects of the rock material

that contains the ground water.

Direct Measurement Methods

A small number of borehole probes (tools) directly measure certain water chemistry

properties. For example, special probes have been developed that measure chloride and

dissolved oxygen. Other special probes directly measure water quality properties such as

pH, temperature, and conductivity.

Other borehole tools include water-sampling mechanisms (thief samplers); although not

strictly borehole geophysical probes, these devices commonly are associated with geophysical

logging and often use the same wireline as is used to support geophysical probes. Unfor-

tunately, direct-measuring chemistry probes are few, and, accordingly, indirect methods,

such as correlation of resistivity to water chemistry, are used as surrogates.

Indirect Measurement Methods

Numerous data have been collected that relate resistivity of water to the concentrations

of dissolved solids, sodium, or chloride. In general, these relations are appropriate for saline

water (herein, water with dissolved solids concentrations exceeding 700 mg/L is considered

slightly saline and water exceeding 2000 mg/L is considered saline). Nearly all borehole-

geophysical logging interpretive techniques developed for the oil industry are based on

sodium chloride (NaC1) saline water. Numerous interpretive techniques are available from

the oil industry. Many of these techniques use a resistivity measurement of water based on

a saline, NaC1 water.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-50-2048.jpg)

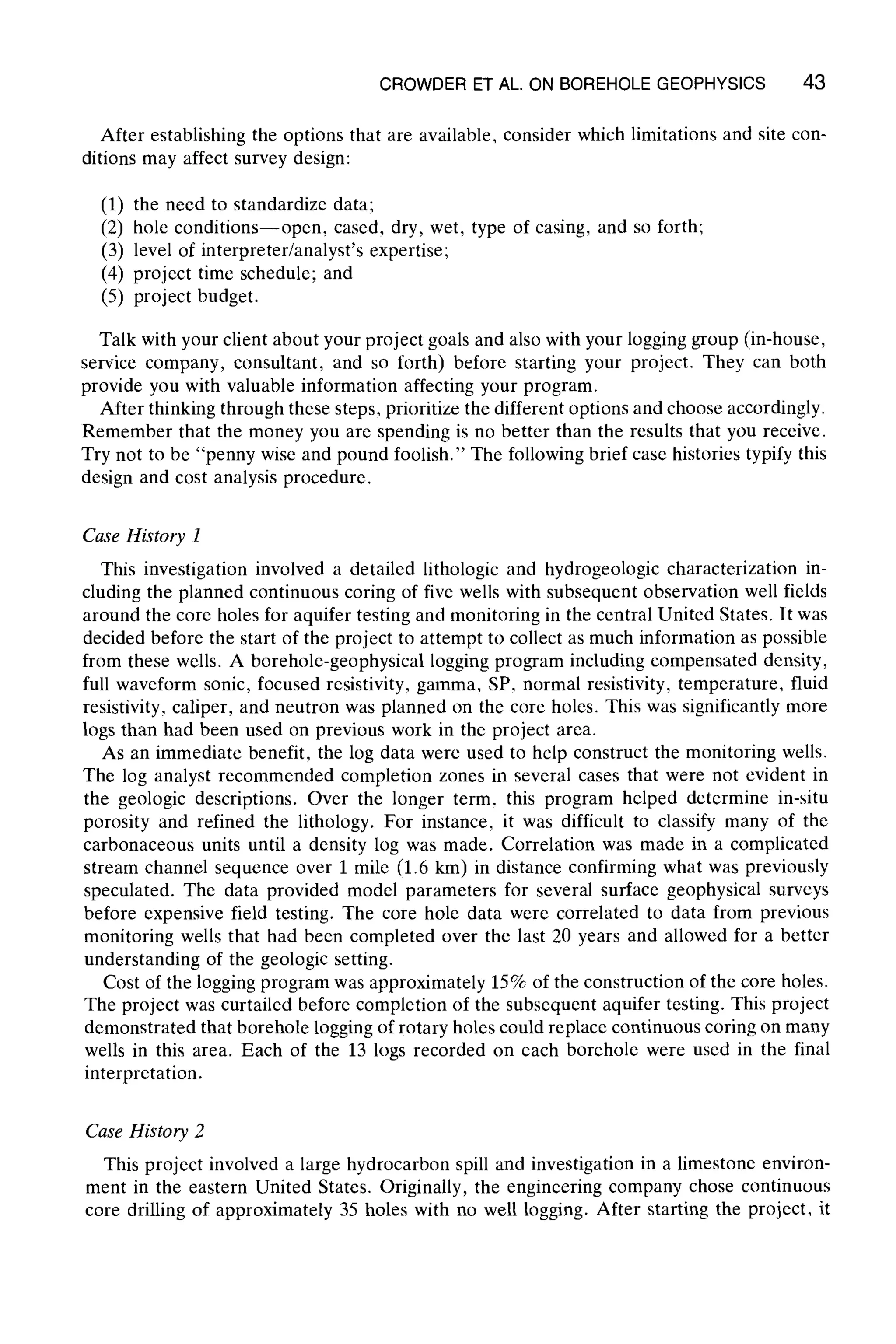

![JORGENSEN ON ESTIMATINGWATER QUALITY 49

Resistivity and Water Chemistry

Water resistivity is a measure of the resistance of a unit volume of water to electric flow

and is related to water chemistry and temperature. Water that contains a small concentration

of dissolved material has a large electrical resistance. Water that contains a large concen-

tration of dissolved solids has a smaller resistance. Quantitative techniques are available for

identifying water resistivity, which is a characteristic that can be related to the chemistry of

the water. The relation of dissolved solids and common chemical constituents to water

resistivity commonly is known (see Appendixes A and B) or can be determined experi-

mentally for the specific water.

The relation of reslstwlty to water chemistry in freshwater (dissolved solids less than 700

mg/L) is a function of specific ions present and has been described by Biella et al. [7], Jones

and Buford [8], Alger [9], Pfannkuch [10], Worthington [11], Urish [12], and others.

Thus, to use oil industry techniques, the relation between resistivity of freshwater and

the resistivity of equivalent NaCI water needs to be developed. Investigators such as Jones

and Buford [8], Alger [9], Turcan [13], and Desai and Moore [14]related the dissolved ions

of naturally occurring ground water to the properties of an equivalent NaCl water. Because

ionic activities are inversely proportional to the water resistivity, they can be used to estimate

resistivity. Alger [9] states:

The relationship between concentration for other ions (other than Na and C1), differ from

that of NaCt. Listed below are multipliers required to convert concentrations of commonly

encountered ions to equivalent NaC1 concentrations.

Na + = 1.0 C1- = 1.0

Ca ++ = 0.95 SO;- = 0.5

Mg ++ = 2.0 CO~-- = 1.26

HC03 = 0.27

These multipliers are based on activity of ions in dilute aqueous solutions. For the above

ion relations, the parts per million concentration (ppm) of the ion in the water is multiplied

by the appropriate factor. The resulting calculated concentration is the equivalent concen-

tration of sodium chloride (C~qN~a) that would have the same resistivity as the freshwater

(RWeq) or:

Rweq = Rw a Cfw (1)

CeqNaCl

where Cfw is the concentration of dissolved solids of the freshwater and Rwa is the apparent

Rw of the freshwater obtained by using values in Fig. 1 [15].

For example, if the sum of the concentration of the dissolved ions (dissolved solids

concentration) in a solution at 75~ (24~ is 500 ppm, the apparent resistivity of the water

(Rw~) would be 10 II 9m. If the sum of NaCI equivalent dissolved ions is 280 ppm, the

water resistivity of an equivalent NaCI solution would be:

RWeq = l0 X 500/280 = 17.6 f~" m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-51-2048.jpg)

![JORGENSEN ON ESTIMATING WATER QUALITY 51

SPONTANEOUS

POTENTIAL

20+

~,~ ~g-MILLNOI.TS

,

.ES,STM~. I. O..-.ErERs ~rE~J.toa

Q2 ~.o ~o ,oo loooz ~o

m i I / i

z MEDIUM IND~ICTION

0.2 ~.o, ,o ,p ,~._~.

DEEP INOIJCTION

'l 0.2 ~O 10 100 1000 2r

t~

~Mecliumi~ tu~on

/,

2,000

..J

2,100-

pinduction./

FIG. 2--Electric logs (spontaneouspotential and resistivity) (fromJorgensen [6]).

in Fig. 3. Each deeper sandstone contains water of increased salinity. Two resistivity traces

are shown--a "deep" and a "shallow" trace. "Deep" implies the resistivity measurement

is of material at some distance from the well bore. In addition, it is commonly accepted

that deep resistivity measurements are more representative of undisturbed formation water

and rock. The "shallow" trace measures the resistivity of the material adjacent to the

borehole. Similarly, it is commonly accepted that this resistivity is most likely to be affected

by the invading drilling fluid. Several methods can be used to estimate water resistivity;

they are discussed below.

Qualitative Methods

Two little-known but easy-to-apply methods for qualitatively estimating relative water

resistivity use the resistivity log and the spontaneous potential log. Within Sandstone D,

the resistivity results as measured by both the shallow and deep traces are equal (Fig. 3).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-53-2048.jpg)

![52 GEOPHYSICAL APPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

ELECTRICLOG

Spontaneouspotentia,_~Depth,~ Resistivity__

t Shale I i

t~-

SandstoneI

wmf I W=~ j

IS4mdmo~ T---"

ShakD Sat~eh~i I

fresh

,,,~ i __1 J

I Sa~ll /

/

D

,,w, I ~

FIG. 3--1dealized electriclog of shale and sandstone section containingfresh and saline water (from

Jorgensen [6]).

If invasion of drilling fluid occurs, the formation water resistivity can be assumed to be

equal to the invading fluid resistivity (mud filtrate) as measured by the shallow curve. If

the resistivity of the mud filtrate and the invading fluid are equal, then the formation water

resistivity is equal to the mud filtrate resistivity. Mud filtrate resistivity usually is measured,

and its value can be obtained by correcting the value reported on the log heading for

temperature. The unique condition described above is useful in quickly determining Rw at

one point and qualitatively evaluating Rw for the overlying and underlying aquifer material

if other factors affecting Rw are equal each formation.

Spontaneous potential (SP) largely is a function of the logarithm of the ratio of the ionic

activity of the formation water to the mud filtrate. Therefore, for the SP deflection to be 0

as shown for Sandstone D in Fig. 3, the ratio is 1 and the activities are equal. If resistivity

and ionic activities are assumed to be inversely proportional, which is the usual assumption

in interpreting SP logs, it follows that the resistivity of the water equals the resistivity of

the mud filtrate, which usually is recorded in the log heading. This unique condition is useful

in quickly estimating the water resistivity at one point and for qualitatively evaluating the

relative water resistivity in overlying or underlying permeable material if other conditions

are equal.

Spontaneous Potential Method

The two quantitative techniques typically used to estimate water resistivity are: (1) the

spontaneous potential method and (2) the cross-plot method. Both methods usually are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-54-2048.jpg)

![JORGENSEN ON ESTIMATINGWATER QUALITY 53

presented in well-logging manuals and texts. However, information as to the accuracy of

the methods is not presented. The SP method is most commonly used and will be presented

first. A comparison of estimated to measured water resistivity values will be made to evaluate

the use and accuracy of the method.

The SP method is reported to be useful in estimating the resistivity of sodium chloride

water. The method is widely known and described in nearly all texts and well-logging

manuals, such as the Application of Borehole Geophysics to Water-ResourcesInvestigations

[16], and is based on the equation:

SP = - K log Rmf 2mrRw K log (2)

where SP is the spontaneous potential, in millivolts, at the in-situ or formation temperature;

K, in millivolts, is a constant proportional to its absolute temperature within the formation;

Rw is resistivity of water, in ohm-metres, at in-situ temperature; Rmf is the resistivity of

mud filtrate in ohm-metres; Aw is the ionic activity of the formation water; and Amf is the

ionic activity of the mud filtrate, also at the in-situ temperature. This method requires SP

values from an electric log and the mud filtrate resistance measurement, which usually is

recorded on the log heading. The SP value is the deflection difference between the shale

line and the adjacent permeable material and can be either positive or negative.

The SP method commonly is used because of the ready availability of SP logs (there are

more electric logs available than any other type of geophysical log). This method of estimating

water resistivity is reportedly useful in sand-shale sections in which good SP differences

exist, and, reportedly, it is not usable or works poorly in carbonate sections [17, p. 3].

However, the assumption that the SP method works poorly in carbonate is questionable

because no terms exist in Eq 1 that refer to lithology. The suitability of the method depends

on the SP difference not on a specific lithology.

An algorithm similar to the one presented by Bateman and Konen [18]for using SP to

determine Rw is shown in Fig. 4 [6]. Mud filtrate resistivity values (Rmf) at a specific

temperature (Tmf) and the in-situ temperature of the permeable material (Tf) at which the

SP is measured are necessary. The SP value, in millivolts, is the signed ( + or - ) difference

between the potential of the aquifer material and the potential at the reference shale line

(vertical line along which most shale or clay sections plot). If the value of Rmf is not known,

an estimate of Rrnf may be made from the mud resistivity (Rm):

Rmf ~ 0.75 nm (3)

The in-situ or formational temperature (Tf) is seldom known unless a temperature survey

has been made in the borehole sometime after drilling has been completed. However, 7f

may be estimated if the temperature between the mean annual temperature existing near

surface (Tma) and the temperature at the bottom of the borehole (BHT) is increased linearly

with depth; mathematically it can be shown as:

Tf ~ Tma + (BHT - Tma)(Df)

Dt (4)

where Dfis the formation depth and Dt is the total hole depth at which BHT was measured.

A second and similar method of estimating Tf uses information on the geothermal gradient

in degrees per unit depth of the area:

Tf ~ Tma + (geothermal gradient)(Df) (5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-55-2048.jpg)

![54 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONSFOR GEOTECHNICALINVESTIGATIONS

Rm~, Tmt SP, "/']

L ,(Tml+7) g

Rm[75=RmI~ Rm[

Rmte

NO ~ YES Rra/75

,,.g, 146.mXTs-sl. ~ I . . . . 2_

_. I __ SP

K=00+0 133 TI

Rw~'-Rml~ lOSP/K T/

Tm]

I''~- ~ 12'~--I ..... )t

[ - - I

-- i

L .-=,-,,(8~/(T1+7)) I

EXPLANATION

Spontaneous potential constant at 9 opecl~ teml~rature

Resistivity of mud filtrate, in ohm-meters

Resistivity of mud filtrate equivalent, in ohm-m~ters

Rersistlvlty o| mud at 75"F. in ohm-meters

Reslstlvlly o| water, in ohm-meters

Resistivity of water equivalent, in ohm-meters

Resistivity of water at 75"F, in ohm-meteN

Spontaneous potential, in mlllivolts

TenpeTalvre ol Iormatlo~ in dcg~re~sFahre~helt ('F)

Temperature ol mud filtrate, in d ~ Fahrenlwit ('F)

FIG. 4--Spontaneous potentialmethod of estimating resistiritv of formation water ffrom Jorgensen

[61).

The procedure for the SP method to evaluate the water resistivity is:

1. Determine Rmf and Tmf. The values are read from the log heading. (If Rmf is not

available, estimate from Rm by using Eq 3.)

2. Determine SP from the spontaneous potential trace on the electric log.

3. Determine Tf from the temperature log or estimate by using either Eq 4 or Eq 5.

4. Determine the formation water resistivity (Rw) by using the algorithm shown in

Fig. 4.

Jorgensen [6] used the SP method to estimate Rw for eleven rock sections for which the

formation water resistivity had been measured. The eleven saturated rock sections tested

were mostly carbonates, which are reportedly not suitable for the SP method. No evidence

was observed to indicate that the method was better suited to sandstone than any other type

of rock material if the shale line for the SP curve could be established; however, only a few

sandstone rock sections were used in the test. Maximum or true static spontaneous potential

(SSP) is not always developed especially when the logged section includes thin layers of clay

and sand. Additionally, if there is considerable clay material in a sand, the log SP will not

represent the SSP.

Results of comparing the Rw estimated from the SP method versus the measured Rw

from the chemical analyses are shown in Fig. 5. A least-squares analysis for a linear relation

indicates a coefficient of determination (r2) of 0.66 for the SP data. A coefficient of deter-

mination of 0 indicates no correlation, and a value of 1 indicates perfect correlation. The

value of 0.66 indicates that some correlation exists. A scatter of about one order of magnitude

might be expected, as shown in Fig. 5. The coefficient of determination of 0.66 may be

typical for the method if the logs usually available from the petroleum industry are used.

This might be interpreted as a very inaccurate estimator of resistivity. However, water](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-56-2048.jpg)

![JORGENSEN ON ESTIMATINGWATER QUALITY 55

100

o_ I

>_

c~ 1.0-

.=,

0.1--

==

0.01

0.01

I

Method of Delermination

Cross pie!

o Spontaneous potential

I i

,~15

z~3

~1 ~4 ~12 0 2

91o~2 o3 ~ ~13o4

8~, o~.14 6~10

5~,7

8,9 ~ ~ o12

I I I

0.1 1.0 10

MEASUREDWATERRESISTIVITY,IN OHM-METERS

lO0

FIG. 5--Measured and estimated resistivity of water (from Jorgensen [6]).

resistivity that occurs in nature ranges from about 0.01 to more than 10 Ft 9m or more than

three orders of magnitude. Thus, for areas that have no measured data and if an estimate

of water resistivity of plus or minus a half order of magnitude is an acceptable range of

accuracy, the method may be used with caution. If additional information from a chemical

analysis of water at a specific zone in the logged hole is available, the correlation between

water resistivity and SP responses can be greatly improved as was demonstrated by Alger

[9].

The accuracy of the method is dependent on the accuracy of the SP measurement. Spon-

taneous potential is difficult to measure accurately because spurious electromotive forces

inadvertentlyare included in the measurement. Equation 2 is most applicable if the formation

water is saline, sodium and chloride are the predominant ions, and the mud is relatively

fresh and contains no unusual additives.

Because water resistivity is a surrogate water quality parameter, its relation to the water

chemistry parameter of interest should be considered in any evaluation of its value as a

water chemistry indicator. For example, Fig. 1 shows that the relation between the con-

centration of NaC1 and resistivityis inverse and not linear. The accuracy of Rw as an indicator

of NaC1 concentration depends on what log cycle Rw exists in, as also shown in Fig. 1.

Cross-Plot Method

The cross-plot method is reported in most logging texts and manuals; however, little or

no discussion is made of the accuracy of this method. The method is discussed in some

detail by MacCary [19]. The cross-plot method is sometimes referred to as the "carbonate"

method or the "Pickett" cross-plot method. This method is not as widely used as the

previously discussed SP method because it requires one or more porosity logs in addition

to a resistivity log.

As the name indicates, the method is based on a cross plot of resistivity and effective

porosity values. (Unless specified otherwise, porosity reported herein is effective or inter-

connected porosity.) Values of porosity and resistivity of saturated material are plotted on](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-57-2048.jpg)

![56 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

log-log graph paper and a line is fitted to the points. Ideally, the points will define a straight

line, and the intercept of the line projected to the 100% porosity value would represent the

Rw. Assuming Archies law is applicable, this hypothesis was tested using data from two

carefully conducted tests on limestone cores (DC & FA #1 and Geis #1) from Douglas and

Saline Counties, Kansas. The cores were saturated with water of a known resistivity. The

results, as shown in Fig. 6, were useful because the projection of a line that fitted most of

the data from the Geis #1 core intercepted the 100% porosity line close to the measured

Rw value. However, DCA & FA #1 core results show that most or nine of eleven data

points fall below the straight line, probably because the Ro values for porosity values less

than 3% may be affected by surface conductance along the grains. (Ro is the combined

resistance of water and the saturated rock.) For formations saturated with freshwater,

Archies law, which is based on the assumption that the matrix is nonconductive and that

surface conductance along grains and ionic exchange are slight, is not accurate. However,

the cross-plot method of observed log resistivity values plotted against porosity values still

should define a curve, which projected to the 100~k porosity intercept will define Rw.

Porosity and resistivity values for the cross plot can be obtained from geophysical logs.

Homogeneous lithology, constant water resistivity, and 100% water saturation are assumed.

Logging devices that "look deep" into a formation provide better Ro values. Suitable logs

might be a deep-induction log (as shown in Fig. 2), a long-lateral log, a deep-conductivity

log, and so forth. (Conductivity is the inverse of resistivity, generally recorded in units of

milliohms per metre or microohms per metre, on geophysical logs.)

Porosity values are best determined from a dual-porosity log (density and neutron), such

as the log shown in Fig. 7. However, other single-porosity logs, such as sonic, neutron,

density, or dielectric logs, could also be used. Porosity determinations using a resistivity log

cannot be used.

100

10

Z

s

1.0

o

Is PL~A130N

D DC~FA BI, Core, doloaoee

o Ge~ 9 I, Core, dokxaoee

x Meamared water r~detNtty

m Cementltlcm (actor

o.1 I 1 I

0.1 1.0 1 0 100 1,00~

RIESlSTfVITYOF ROCK WATER SYSTEM (Ro), I~NOHM-METERS

FIG. 6--Cross plot of resistivity and porosity measured on dolostone cores (from Jorgensen [6]).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-58-2048.jpg)

![JORGENSEN ON ESTIMATING WATER QUALITY 57

CALIPER ~ i POROSITY.IN PERCENT(LIMESTONEMATRIX)

DIAMETERIN INCHES 13 i COMPENSATEDFORMATION-DENSfTYPOROSITY

GAMMARAY,INAPi UNITS Z ~_ 20 10 0 "10

150 ~ I COMPENSATED-NEUTRONPOROSITY

300 ~ 130 20 lo o -1090 ~ ~ ........................L

j 1,900 '

ii I

~'Caliper l

r i

I

I'

_-

,~Gamma ray

_

P

__ L

2,000

i

i

+] 2,100

i

iI

i

I

i

Sandstone

i -)

Densityporosity~ ~ ~.

i !% 5

i ~Neutron Porosity

FIG. 7--Dual porosity, gamma-ray, and caliper logs (from Jorgensen [6]).

When the cross-plot procedure is used after determining porosity with a graph like

Fig. 8, it is not always possible to select points defining a straight line to the degree of

desired accuracy. Logs that have expanded depth scales are more easily used in selecting

suitable porosity and resistivity value sets because it is possible to locate the same point on

all the logs more accurately. An example of the method is shown in Fig. 9. The data plotted

in Fig. 9 were picked from the logs shown in Figs. 2 and 7.

If the rock section is not 100% saturated with water, the rock-water system resistivity

(Ro) values obtained from the log will be larger than the Ro values of the aquifer material

if it had been 100% saturated. The values would plot to the right of the line defining n

compared to Ro for a 100% water-saturated section. The unusually large resistivity values

may indicate an unsaturated zone, hydrocarbons, gases, or unconnected porosity. Unusually

small resistivity values might indicate that clay minerals occurred in some rock sections.

Because the cross plot of porosity and resistivity logarithms defines a straight line, standard

least-squares techniques can be applied to determine the standard estimate of error. Ac-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-59-2048.jpg)

![58 GEOPHYSICAL APPLICATIONS FOR GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATIONS

2o]

~Sulfur

] ~s=,

221

,,=,

2.3,-

o=

2.4;

'

2.6

== i

2 7 ~

i

28!

i

301

FRESHWATER,LIQUID-RLLEDHOLES

i

i

EXkMPI.E

D~emmlM Porosi~r(;i~en:

nS=9

n~=t9

n=14

dl'l 0

Langm~eirtitli

&

Polyhliitl

tJ

o m ~o -3o

PO~IOSITYFROM NEUTRON LOG (nn), IN PERCENT (APPARENTLIMESTONE POROSITY)

24o

d

~2s

w

-2o~.

x

E'o ~,

-- 8

:o g=

~-10

4

~-15

FIG. 8--Porosity and lithology from the formation density log and compensated neutron log (modified

from Schlumberger [20]).

cordingly, the standard estimate of error for Rw can also be defined. Note the estimated

Rw that is determined is for formation conditions.

Jorgensen [6] tested the accuracy of the method by estimating Rw for 15 rock sections

for which Rw had been measured. The coefficient of determination of 0.88 was determined

from a least-squares analysis. The value of 0.88 may be typical of estimates that are based

on usually available logs. Inspection of Fig. 5 shows variations or scatter of about one order

of magnitude in a range of more than three orders of magnitude that can be expected in

nature. Thus, based on the results shown in Fig. 5, the method did not accurately estimate

Rw; however, the method can be used to estimate formation water resistivity for areas that

have no data if an estimated accuracy of plus or minus a half order of magnitude is acceptable.

The accuracy of the method is, in general, proportional to the extent of the range in

porosity that is measured within the section of interest. The wider the range, the more

accurately the line can be defined. Accuracy of reading the recorded measurement from

the log (trace) is improved if the scale is expanded.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-60-2048.jpg)

![Q.

_Z

O

o_

JORGENSENON ESTIMATINGWATERQUALITY 59

Dala Deplh, R,.

poml mleet tf.g2l(hg7

10--

1 2,020 g 5 g 5

2 2026 12 10

3 2.036 18 6

4 2,041 26 3 5

5 2059 6 13

6 2.071 45 16

j 7 2.0~2 6 7

0 ~ L _ ~0

o h m - m e t e r s ~

EX J,'~lI'I,FZ

Determine: Waterre$tstivtty(Rw),r factor(rn),

and formationtemperature(Tt)

Given: Geothermaigradient=6.0[33~Fahrenheii

6 perfoot

Averagedepth= 2055 feet

1c2 o

P Meanannualtemperature=55 Fshrenhelt -

~7 ~ Solution: Rw=Ro at |O0-percentpor =0.38

rn~ 1.37/I = 1.37

Fahrenheit

RESISTIVITY OF THE RCCK-WATER SYSTEM (Ro). IN OHM-METERS

FIG. 9--Cross plot of geophysical log values of Ro and n (from Jorgensen [6]).

The Rw value may be used to estimate water chemistry if the relation has been established.

For example, the sodium chloride content can be estimated for many saline waters if the

in-situ temperature of the water is available or can be estimated. Turcan [13] used resistivity

logs to determine Rw, which were in turn correlated with chloride or dissolved solids con-

centrations. Turcan's analysis indicates that a high degree of correlation can be established

if some water chemistry data are available.

The dissolved solids concentration can be estimated from specific conductance (conduc-

tance at 75~ [24~ usually in units of microsiemens or micromohs per centimetre, if the

relation between the specific conductance and dissolved solids is known. A method of

estimating the dissolved solids concentration in water from specific conductance is given in

Appendix A.

Formation Factor Methods

Sethi [21] presented a comprehensive review of the work of many researchers in defining

formation factor relations. The relation of rock resistivity, water resistivity, porosity, and

tortuosity were first described by Archie [22, p. 56]. Archie, assuming that rock was non-

conductive, gave:

F = n-" (6)

where F is the formation factor (dimensionless), n is porosity (dimensionless), and m is the

cementation factor (dimensionless).

The relation of the formation factor to pressure and temperature is not completely known.

In reference to the temperature effect, Somerton [23, Fig. 12, p. 188] showed that the

logarithm of the ratio of the formation factor at a specific temperature to the formation

factor at a specified reference temperature for the Mississippian Berea Sandstone varied

nonlinearly with temperature change.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geophysicalapplicationsforgeotechnicalinvestigations-151104153926-lva1-app6892/75/Geotechnical-Geophysics-61-2048.jpg)

![60 GEOPHYSICALAPPLICATIONSFOR GEOTECHNICALINVESTIGATIONS

For increasing pressure, Helander and Campbell [24, p. 1], in relation to the formation

factor, report: (1) the formation factor changes as the mean free path for current increases

as constriction closes pores; (2) the degree of constriction, which causes change of the

formation factor, is mostly due to the closing of the smallest pores; and (3) the effect of the

double layer on the formation factor is increased as the pore throat areas decrease with

decreasing porosity.

The cementation factor (m) largely is a function of tortuosity and pore geometry. Tor-

tuosity is the ratio of the fluid path length to the sample length. Aquilera [25] studied the

effect of fractured rock on the formation and cementation factor. He used a double-porosity

model in defining m. The model development implies that m will be near to 1 for a rock

mass in which all porosity is the result of fractures (that is. there is no interconnected primary

porosity). Because the length of the flow path in a fractured medium is much shorter than

the length of the flow path in a porous medium, the tortuositv of the fractured medium is

relatively small, and the cementation factor also is small and is near to 1. The relation of

porosity (n), the formation factor (F), and the tortuosity factor (T)of Bear [26, p. 115] is:

1

F = Tnn (7)

where Tis the square of the ratio of the length of the sample to the length of the electrical

flow path. Archie [22] further defined:

F = Ro/Rw (8)

where Ro is resistivity observed (log resistivity) and Rw is the formation water resistivity.

(Herein, Ro is assumed to be the bulk water and rock resistivity unaffected by fluid invasion,

sometimes termed true resistivity or Rt.)

Accordingly, an estimate of Rw can be made if F is known and a measurement of Ro is

available because:

Rw = Ro/F (Sa)

For example, if Eqs 6 and 8a are combined, the equation becomes:

Rw = Ro n" (9)

If Rw is constant, Eq 9 will produce a straight line with the slope of -m on a log-log plot

of n versus Ro.

Techniques or methods that produce a formation factor can be used to estimate an Rw

value. Pirson [27, p. 24] relates for "clean" rock:

Rxo

F ~ .... (10)

Rmf

where Rxo is the resistivity of the invaded zone of the porous formations around the well

bore. Rxo can be obtained from a microresistivity log, "laterolog 8," spherically focused

micro-laterolog, or a "proximity" log and sometimes a short normal. Rmf is a resistivity