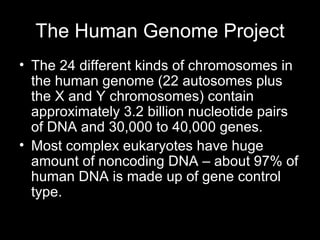

Genomics is the study of whole genomes. In the 1980s, scientists determined sequences of important genes. In the 1990s, the genome of H. influenzae was fully sequenced. The Human Genome Project, begun in 1990, fully sequenced the human genome ahead of schedule in 2003. The human genome contains 3.2 billion DNA base pairs and 30,000-40,000 genes. While genomics provides medical benefits, it also raises safety, ethical, and privacy concerns that remain open questions.