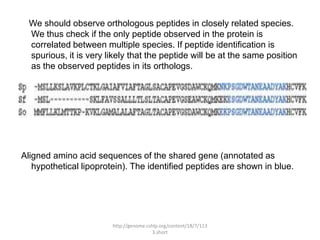

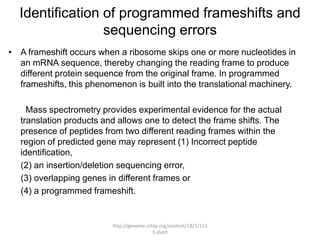

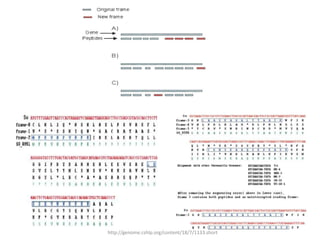

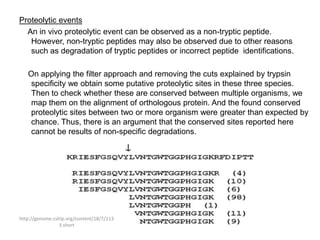

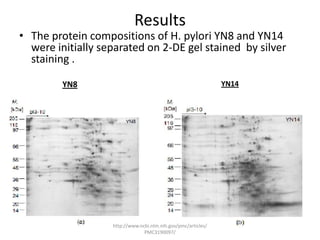

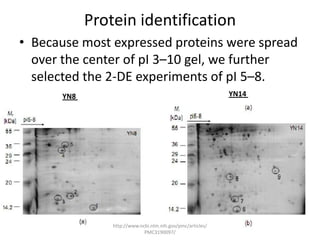

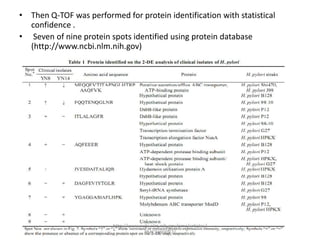

Comparative proteogenomics using mass spectrometry data from multiple genomes can address problems that a single genome approach cannot. It helps identify rare post-translational modifications, resolve "one-hit wonders" by looking for correlated peptides in orthologous proteins across species, and identify programmed frameshifts and sequencing errors. The approach is demonstrated through an analysis of mass spectrometry data from three Shewanella bacteria genomes, improving gene predictions and annotations compared to existing tools.