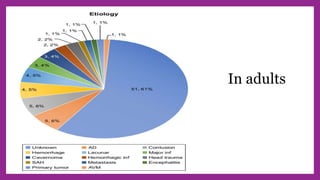

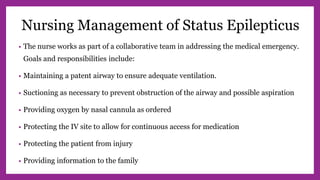

This document provides information on epilepsy, including definitions of key terms, classification of seizure types, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and management. It defines epilepsy as a chronic disorder involving recurrent seizures from abnormal neuronal discharge in the brain. Seizures are classified based on origin point and symptoms. Treatment involves identifying and treating underlying causes, avoiding triggers, suppressing seizures with antiepileptic drugs or surgery, and managing related physiological and social issues. Commonly used AEDs are discussed as well as protocols for managing status epilepticus, an emergency condition.