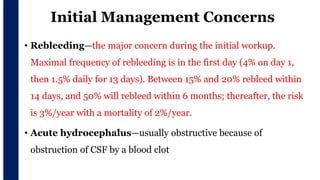

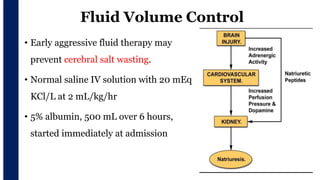

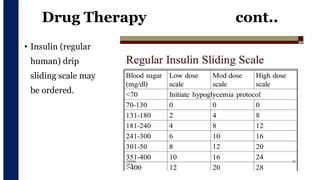

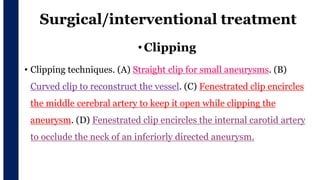

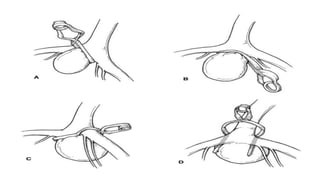

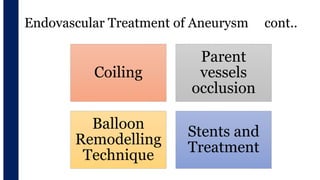

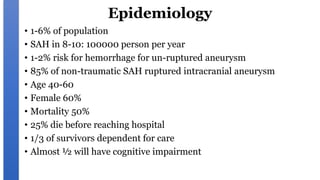

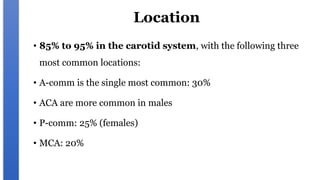

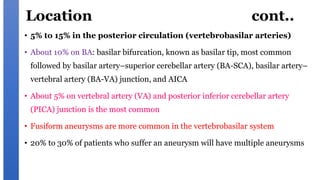

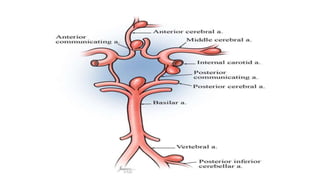

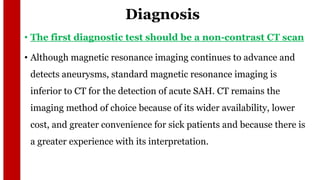

A cerebral aneurysm is a bulging, weak spot on an artery in the brain. It can burst and cause bleeding into the spaces surrounding the brain. The document discusses cerebral aneurysms, including their definition, causes, risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis using CT/MRI/angiography, grading scales, locations, management with fluid/blood pressure control and drugs like nimodipine, and surgical/endovascular treatment options like clipping. The goal of initial management is to prevent rebleeding while maintaining cerebral blood flow and normal intracranial pressure.

![Cerebral Aneurysm

Evaluator: Mr L Anand Presenter: Shruti Shirke

[Asso professor, CON AIIMS BBSR] M.Sc Neuroscience Nursing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cerebralaneurysm-210806045749/85/Cerebral-aneurysm-2-320.jpg)

![Un-ruptured Aneurysm

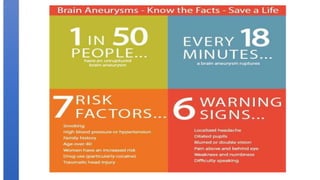

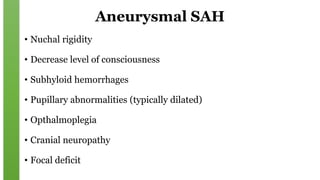

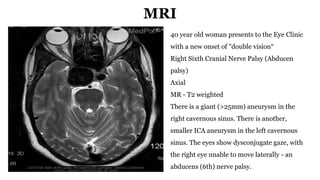

• In approximately 40% of cases, there are warning signs, often called prodromal signs.

• Dilated pupil (loss of light reflex; oculomotor nerve [cranial nerve (CN) III] deficit)

• Extraocular movement deficits of the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV) or

abducens (CN VI) cranial nerves

• Possible ptosis (oculomotor nerve [CN III] deficit)

• Pain above and behind eye

• Localized headache

• Nuchal rigidity (neck pain on flexion)

• Possible photophobia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cerebralaneurysm-210806045749/85/Cerebral-aneurysm-35-320.jpg)

![Unruptured Aneurysms cont..

• Dilated pupil (loss of light reflex; oculomotor nerve [cranial nerve (CN) III]

deficit)

• Extraocular movement deficits of the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV)

or abducens (CN VI) cranial nerves

• Possible ptosis (oculomotor nerve [CN III] deficit)

• Pain above and behind eye

• Localized headache

• Nuchal rigidity (neck pain on flexion)

• Possible photophobia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cerebralaneurysm-210806045749/85/Cerebral-aneurysm-49-320.jpg)