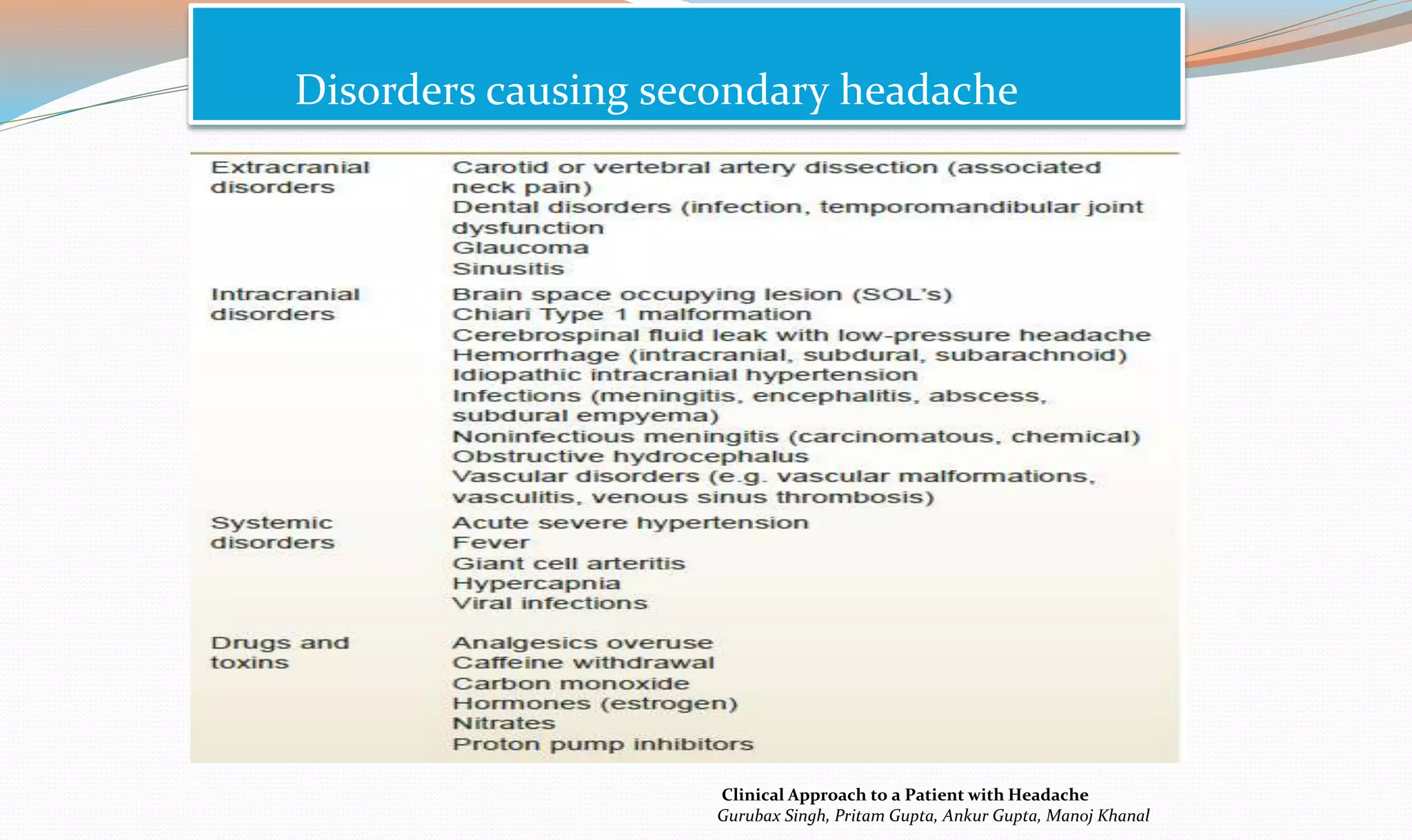

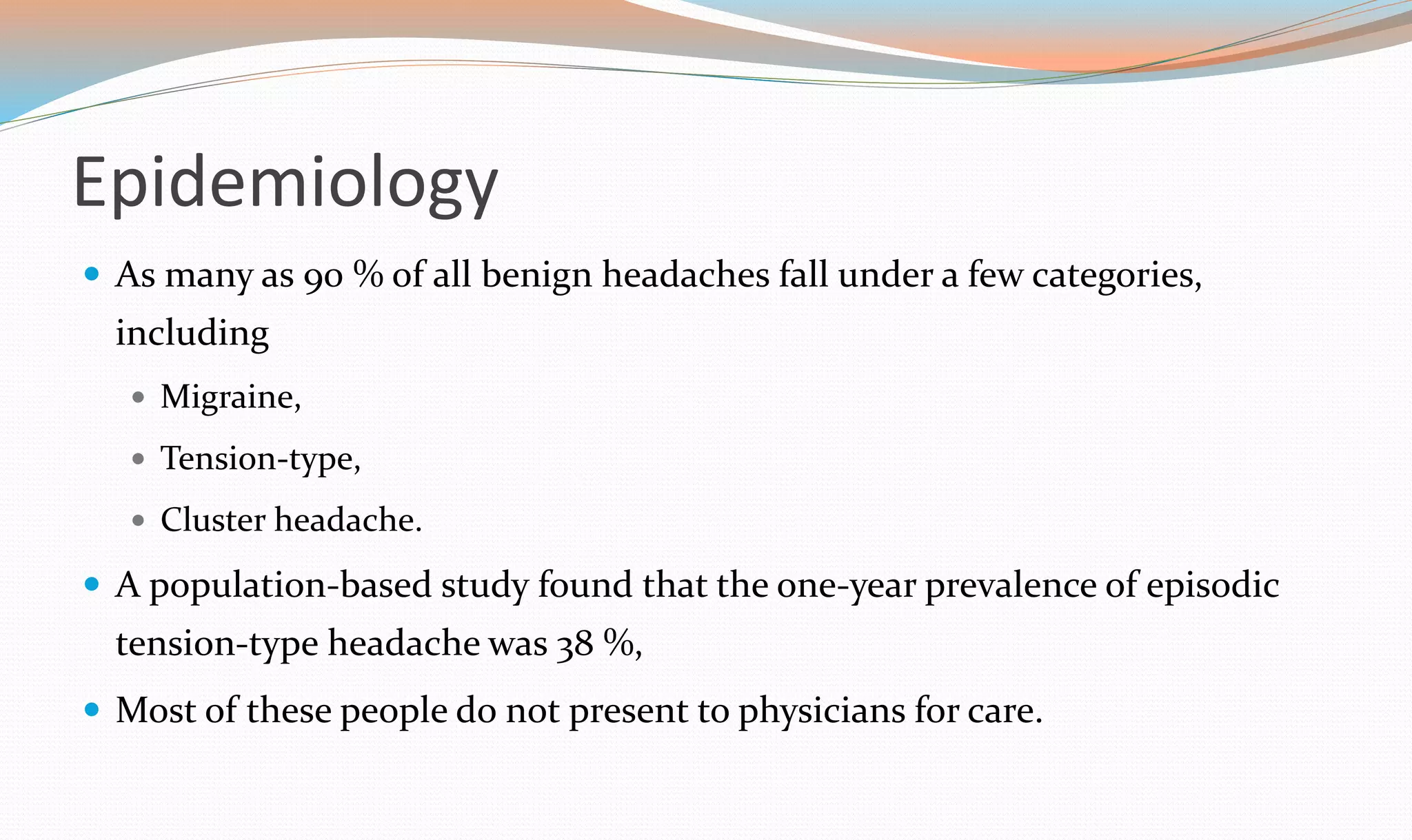

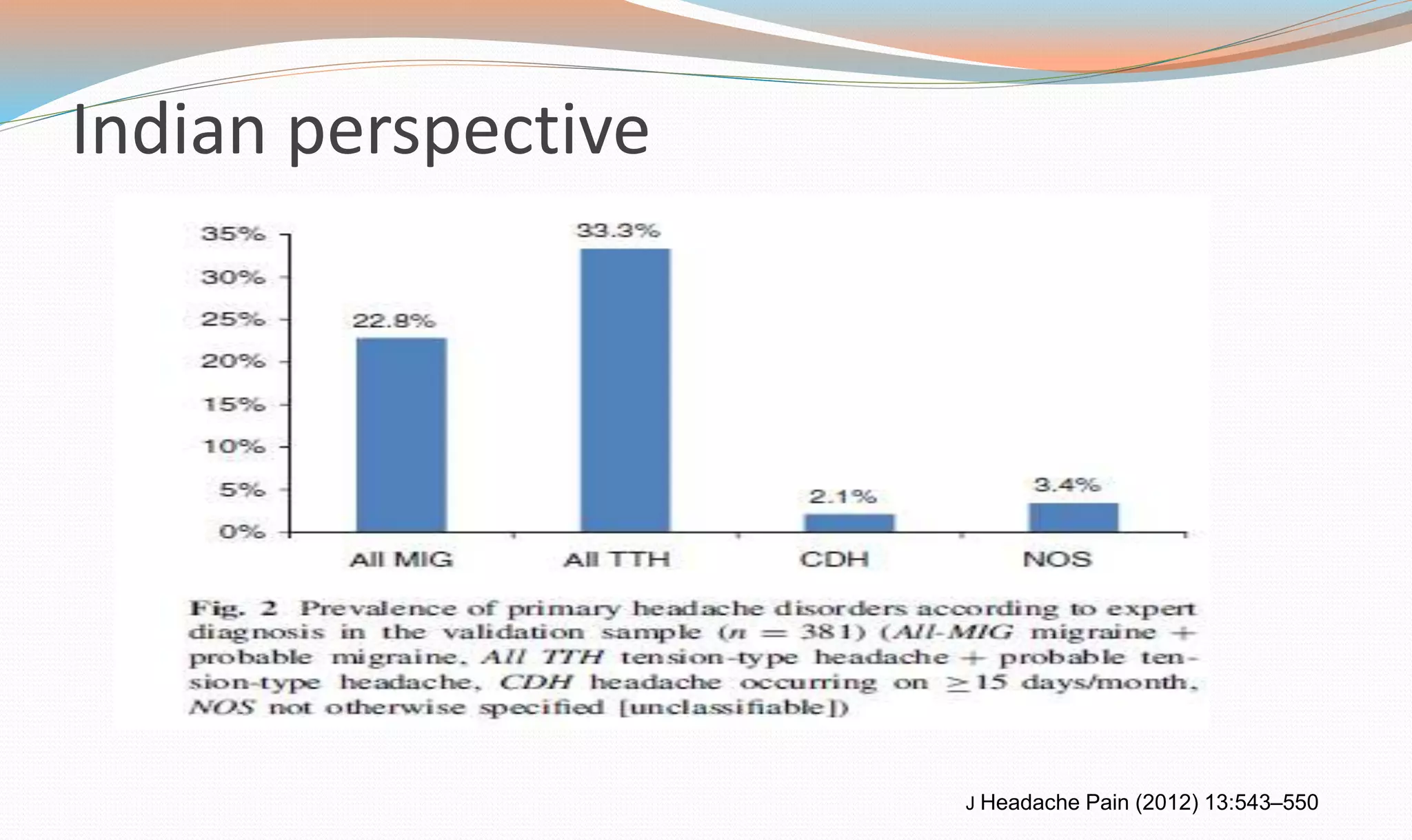

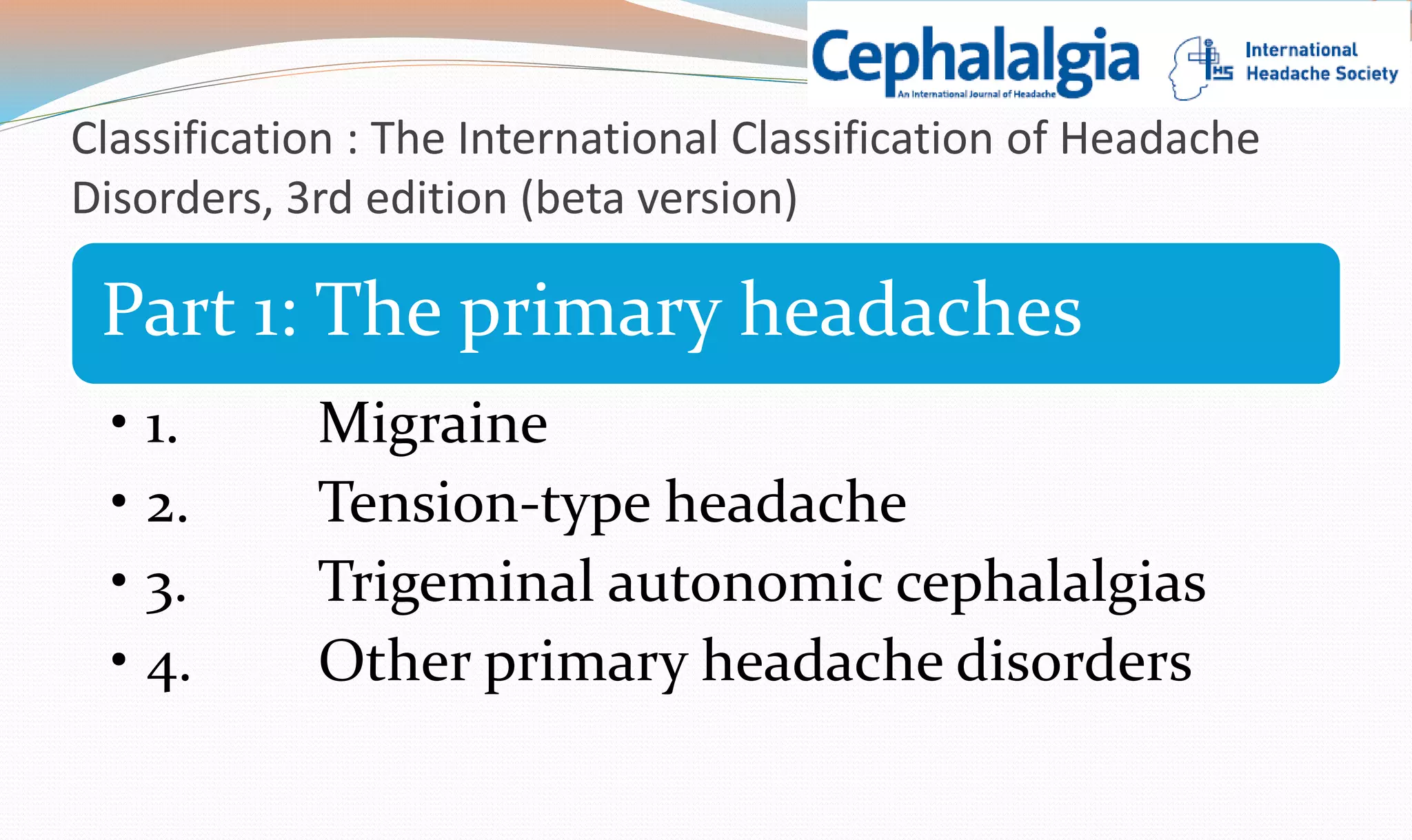

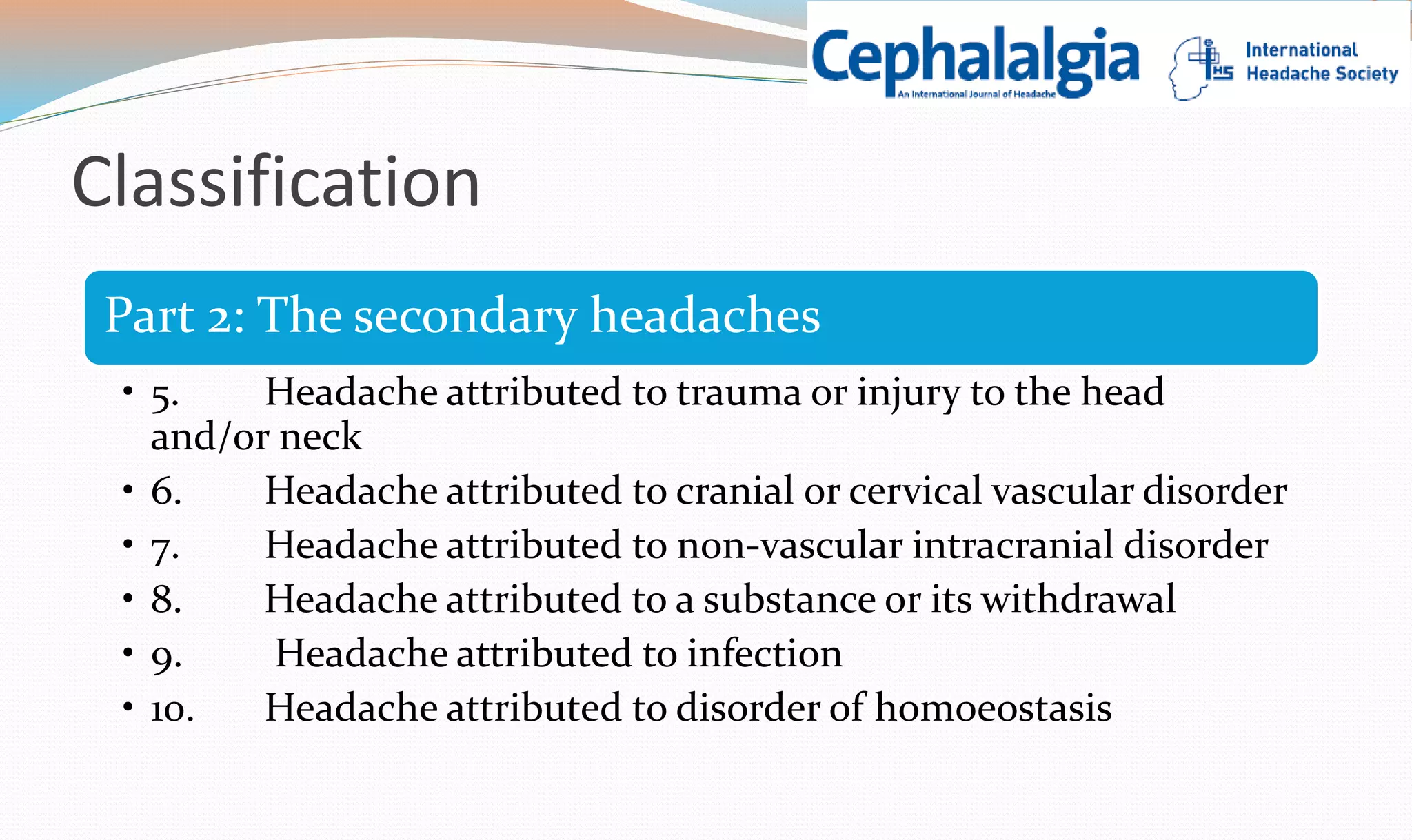

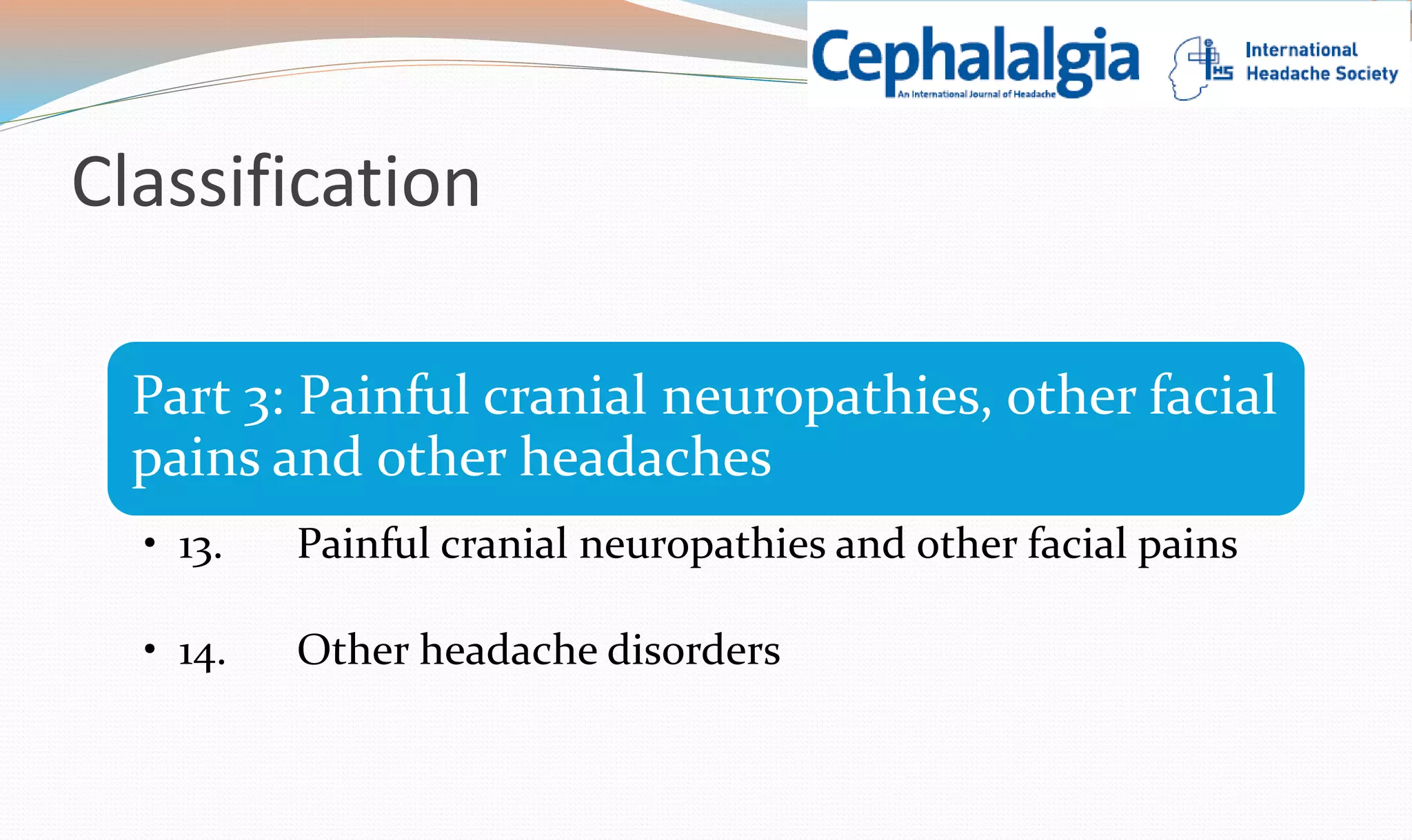

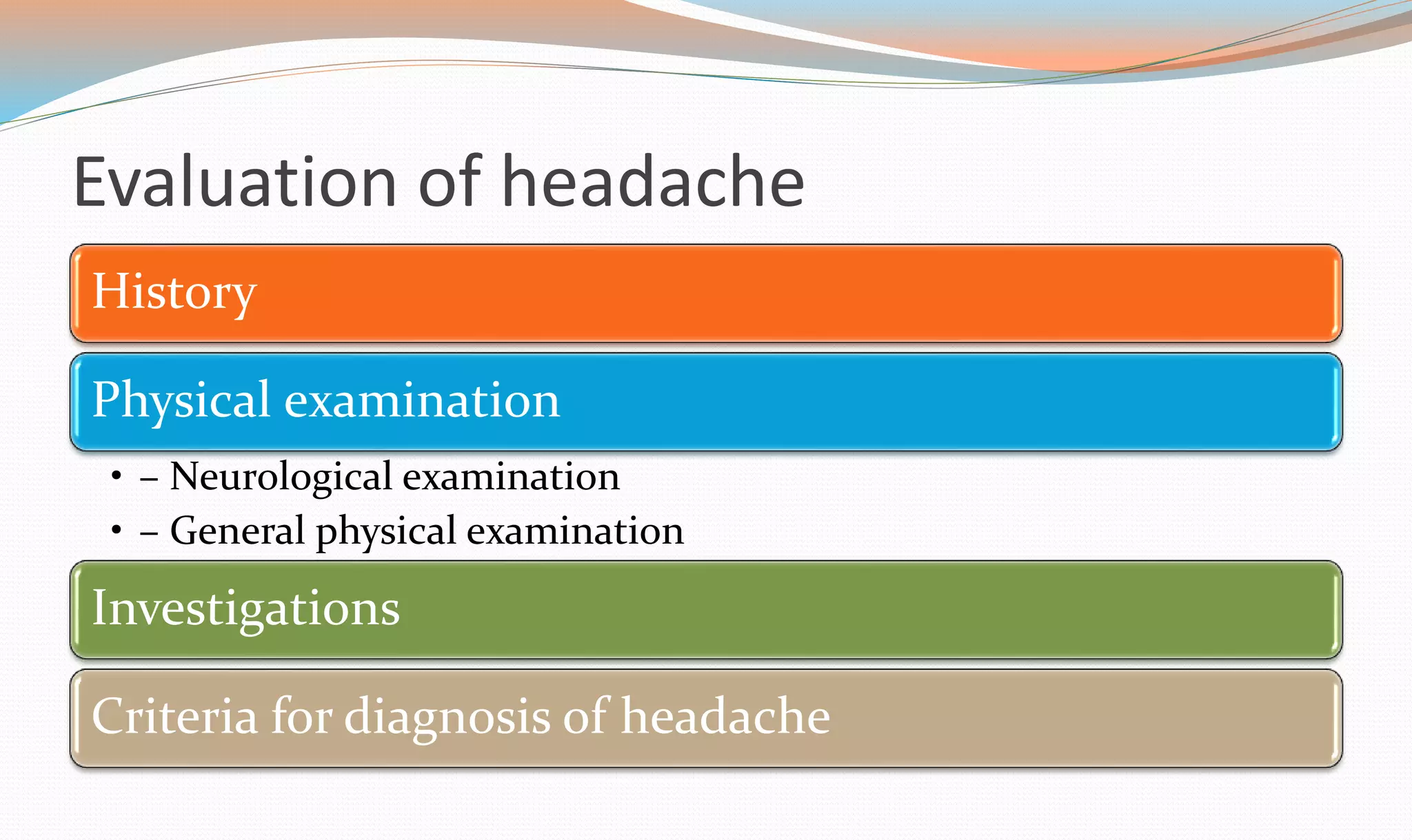

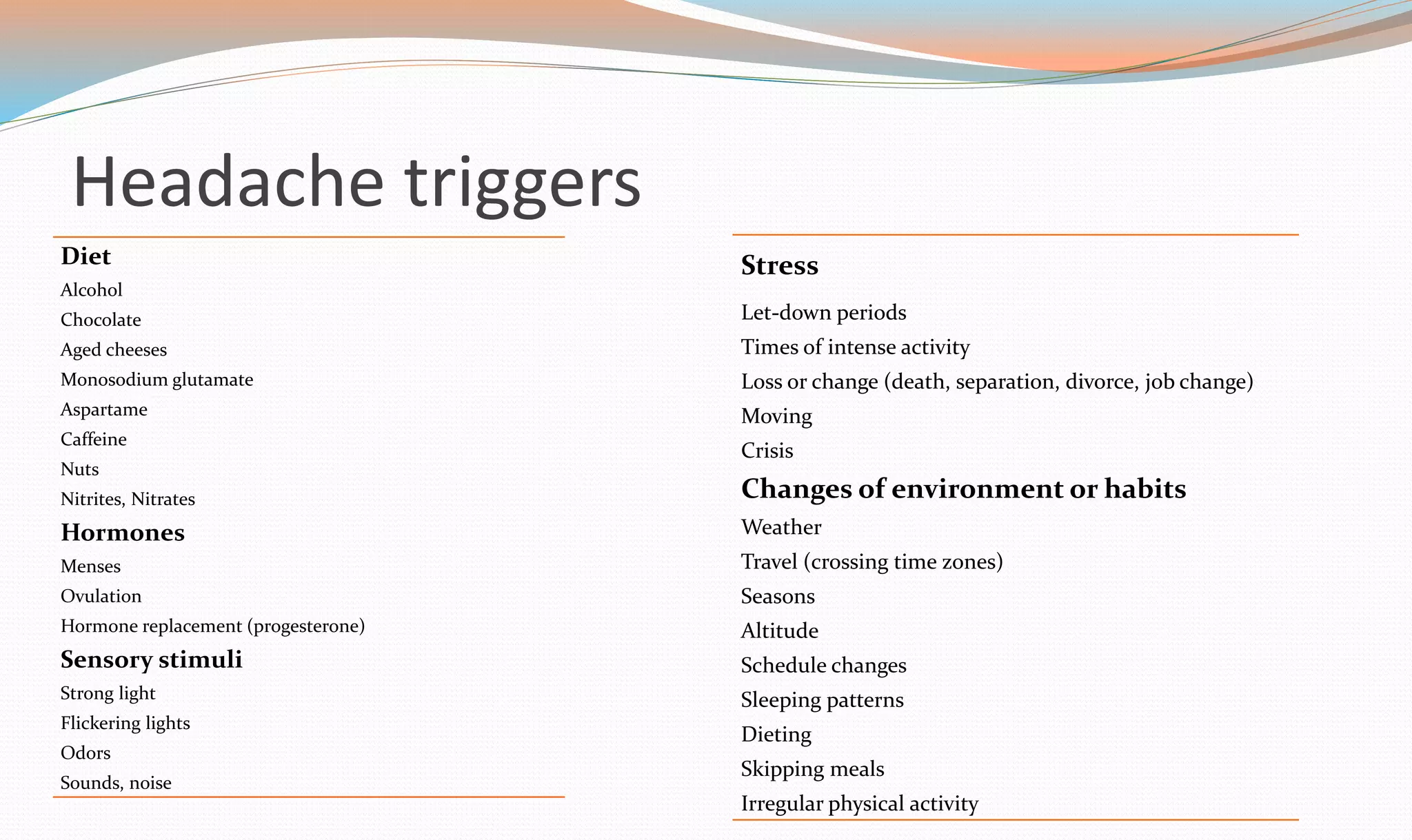

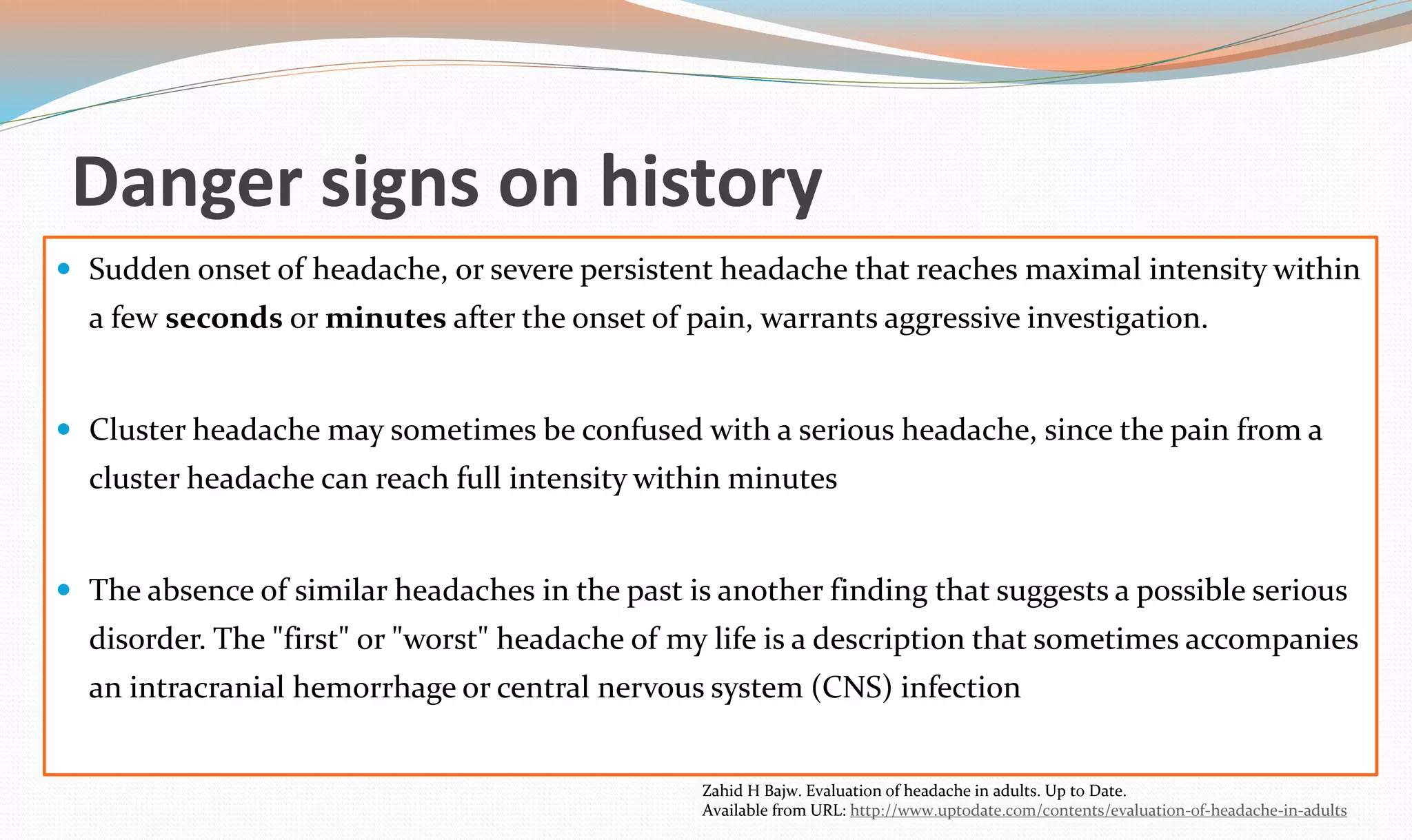

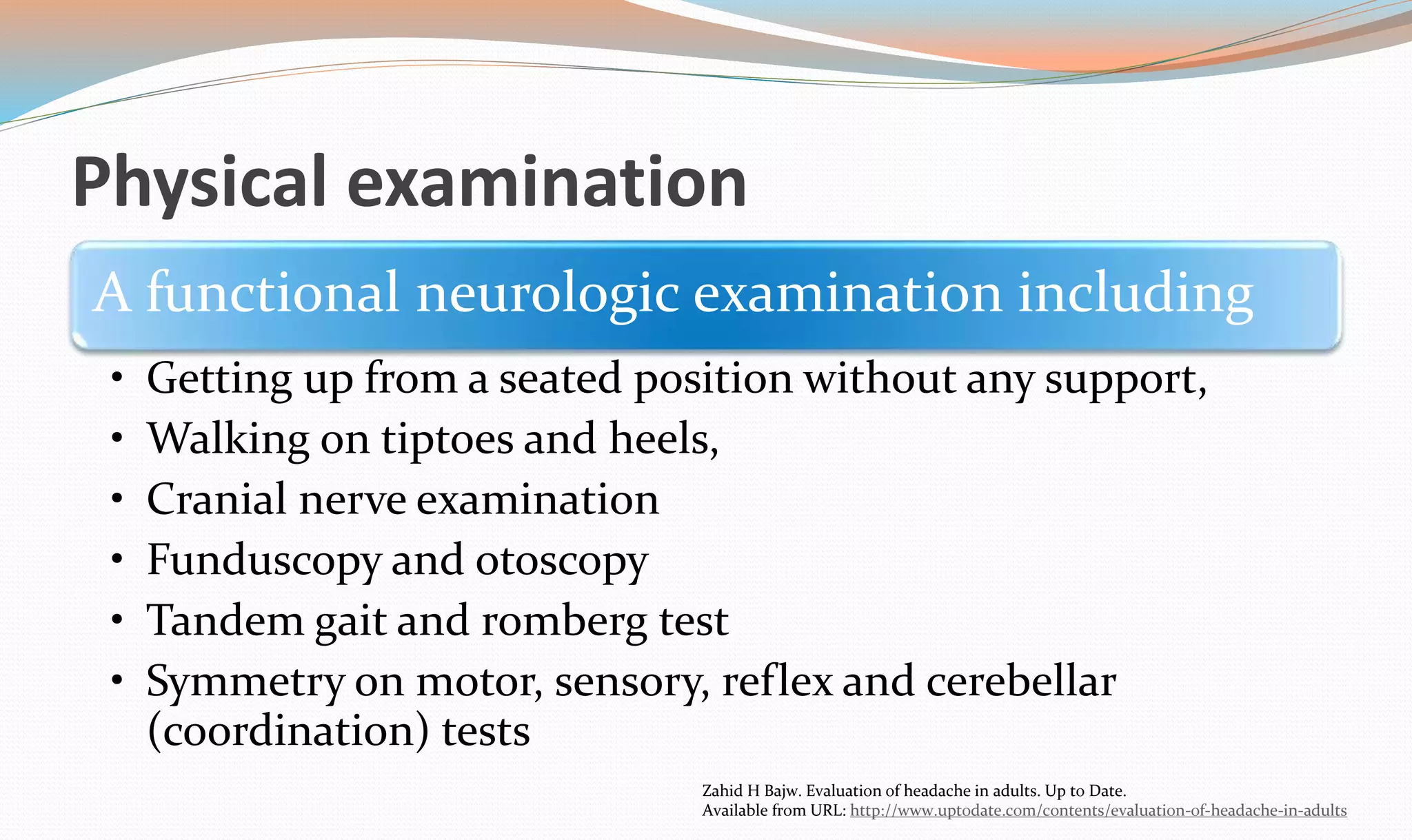

This document discusses headache disorders and their evaluation and classification. It notes that headaches are among the most common neurological disorders, affecting around 47% of adults annually. The most common types of benign headaches are migraine, tension-type, and cluster headaches. A thorough patient history is the most important part of the evaluation, to help identify headache type and risk factors for underlying conditions. Physical examination may include neurological and general examination, with attention to danger signs in the history that suggest further investigation is needed.

![Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging studies (eg, computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance

imaging [MRI]) may detect a variety of disorders that cause secondary

headache, including:

Congenital malformations

Hydrocephalus

Cranial infections and their sequelae

Trauma and its sequelae

Neoplasms

Vascular disorders (such as arteriovenous malformations)

Daniel J Bonthius. Approach to the child with headache. Up To Date.

Available from URL: www.uptodate.com.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headache-141021042914-conversion-gate02/75/Headache-39-2048.jpg)