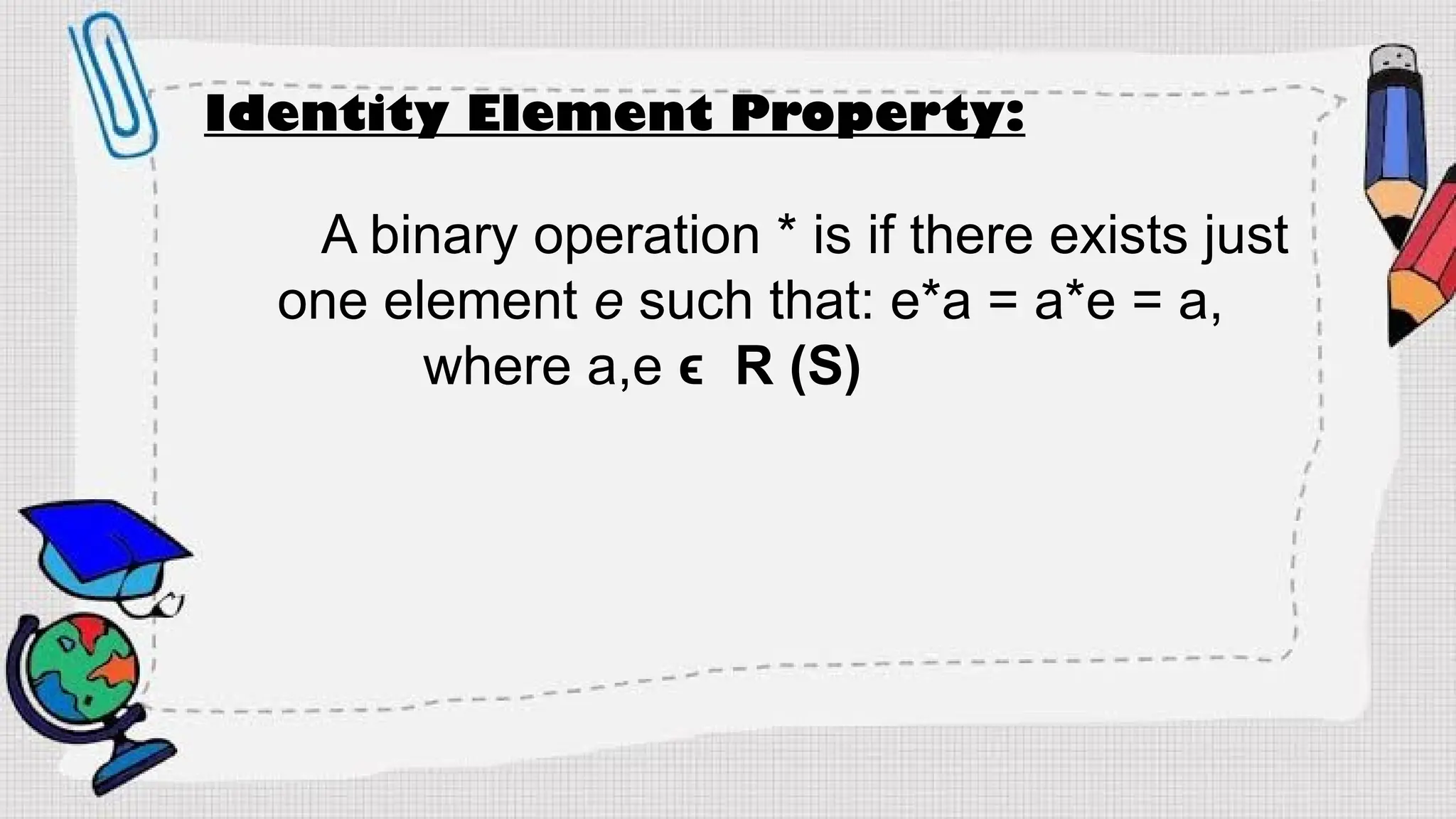

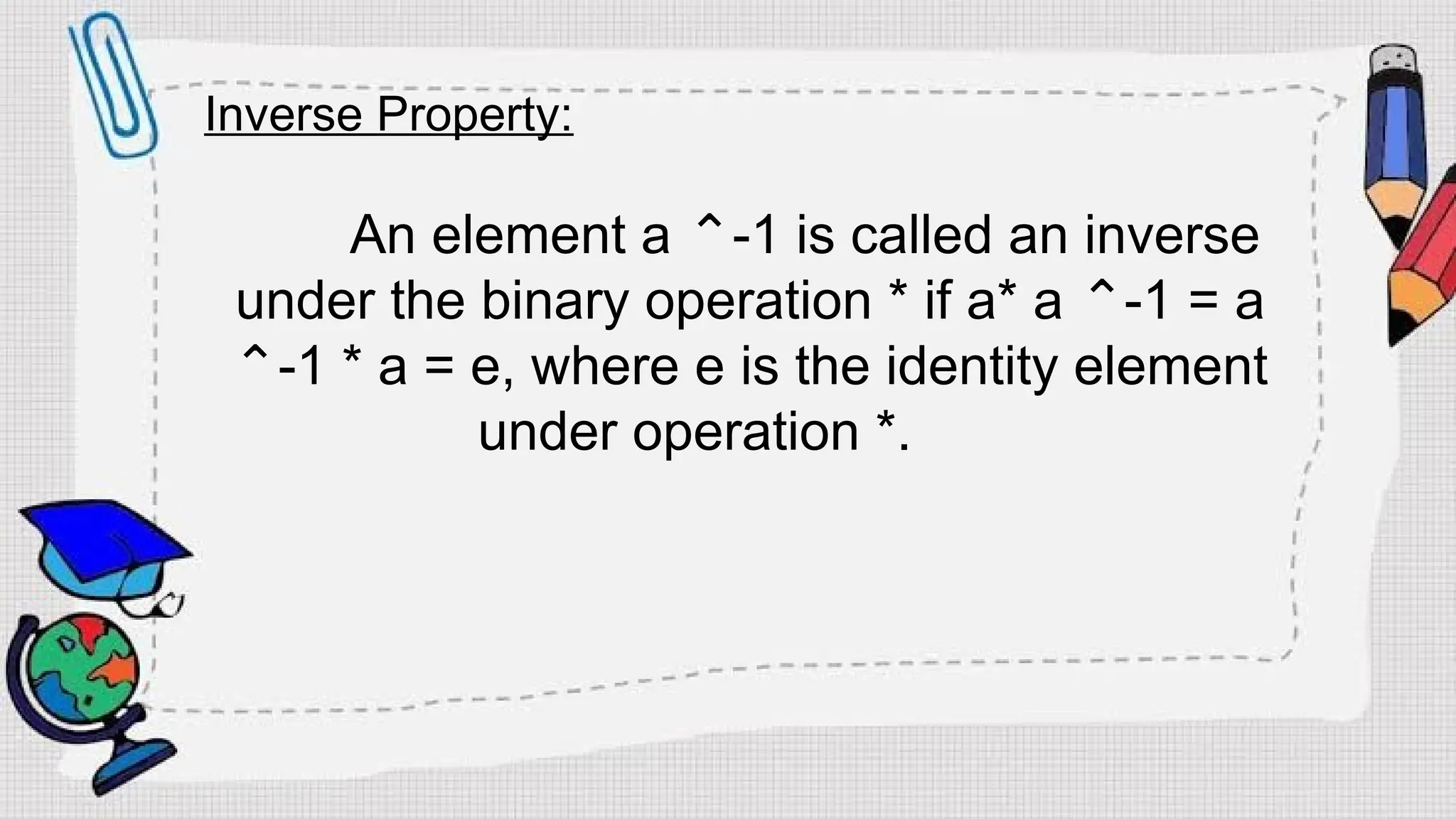

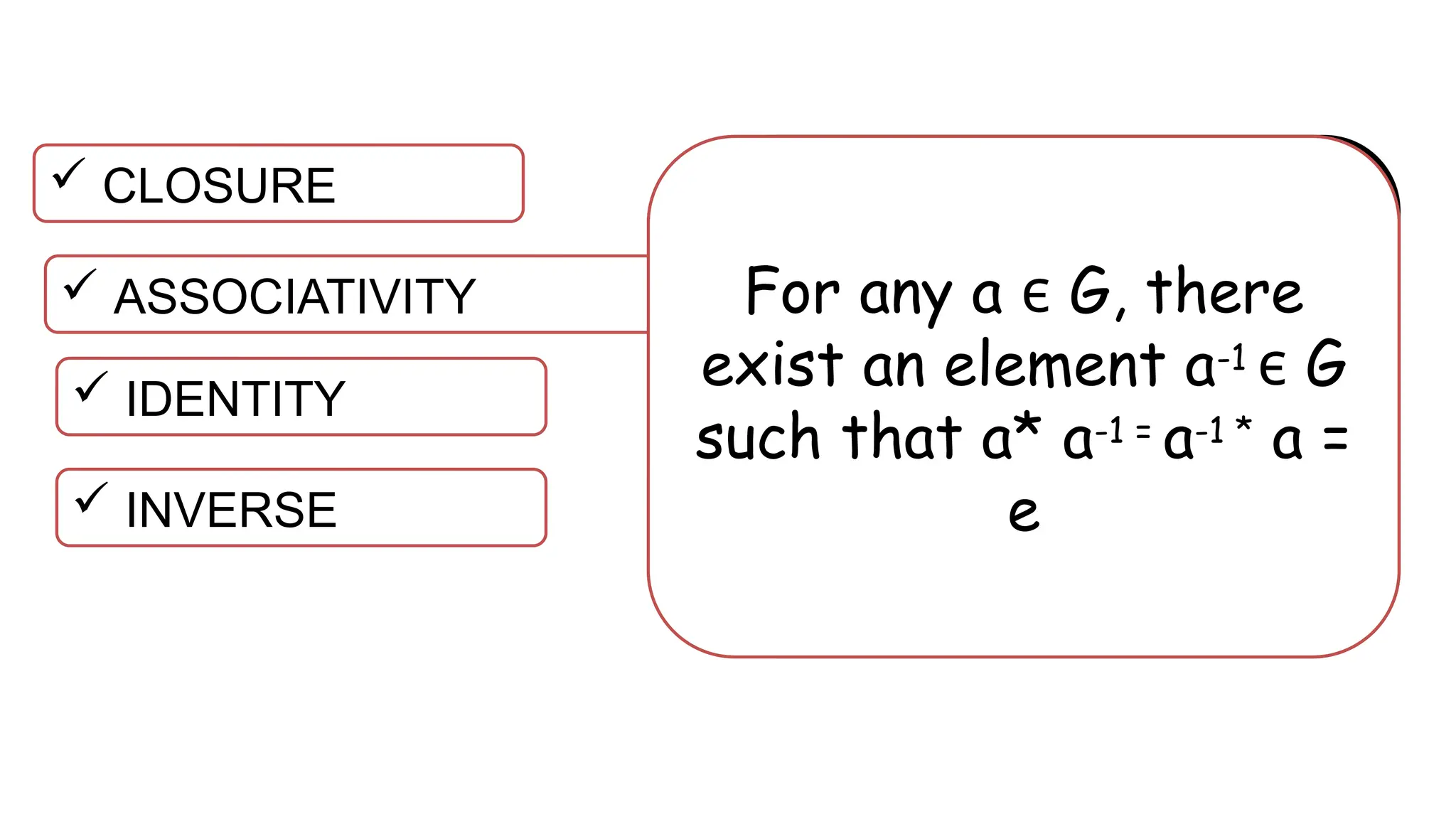

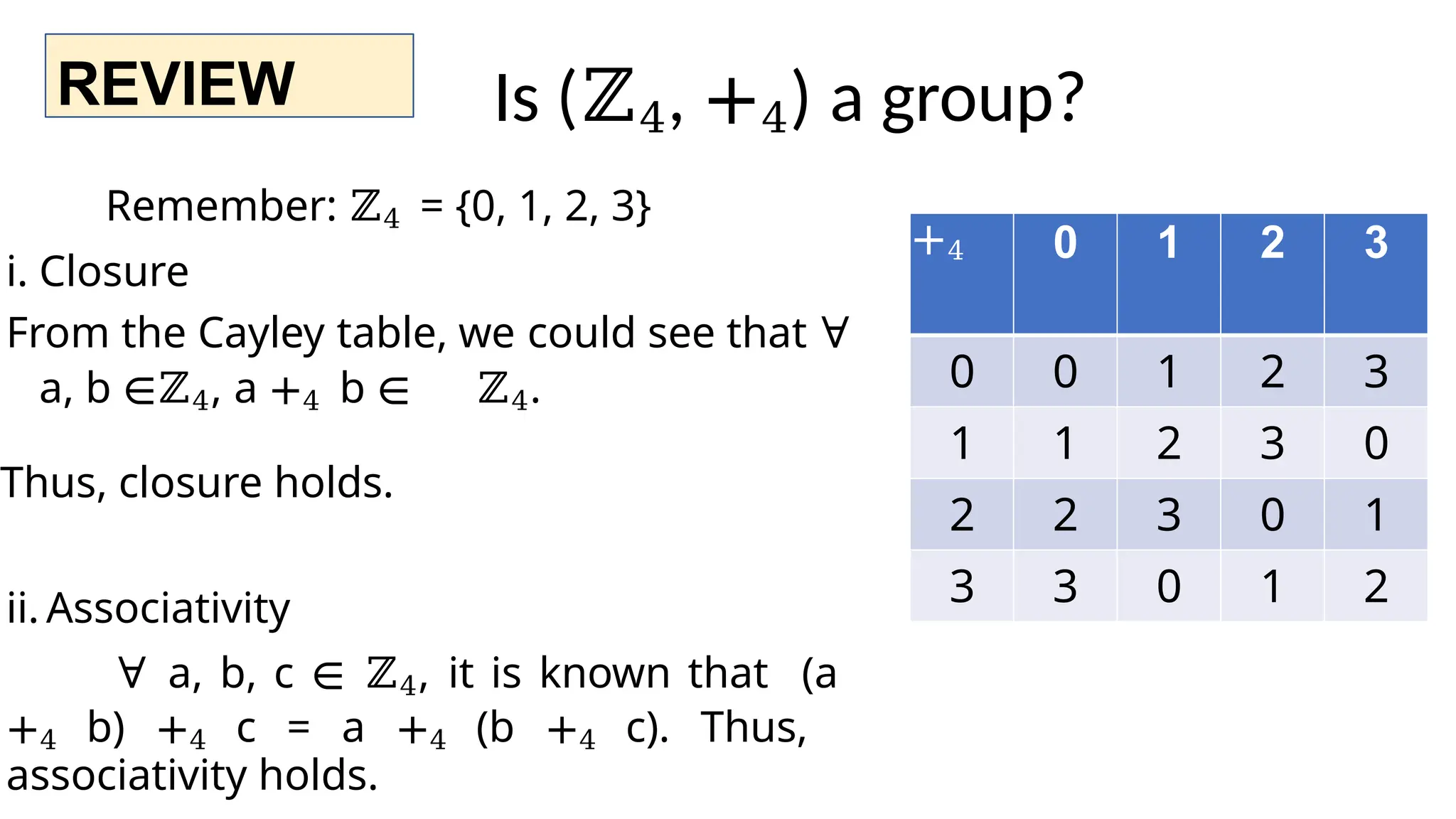

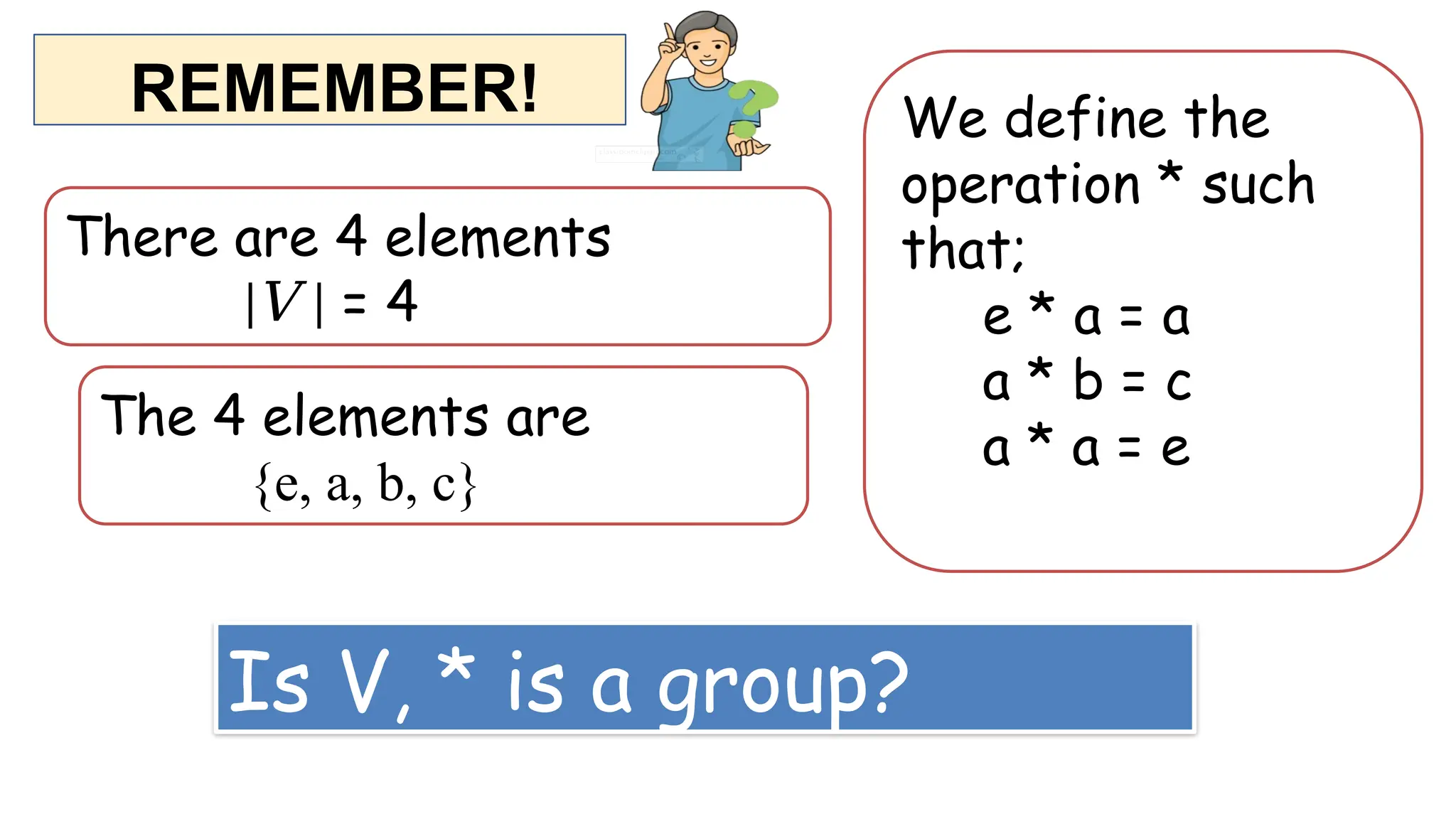

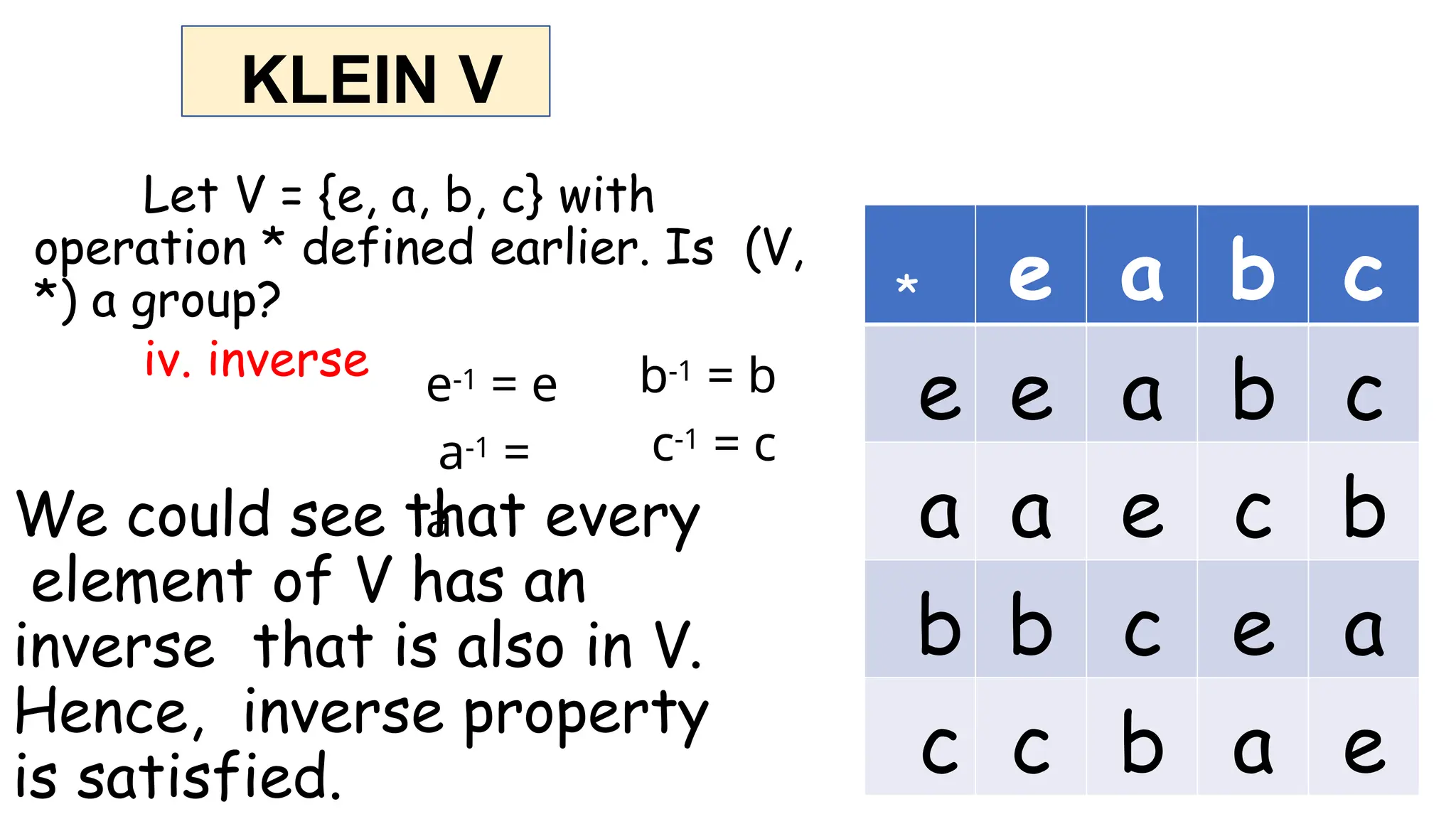

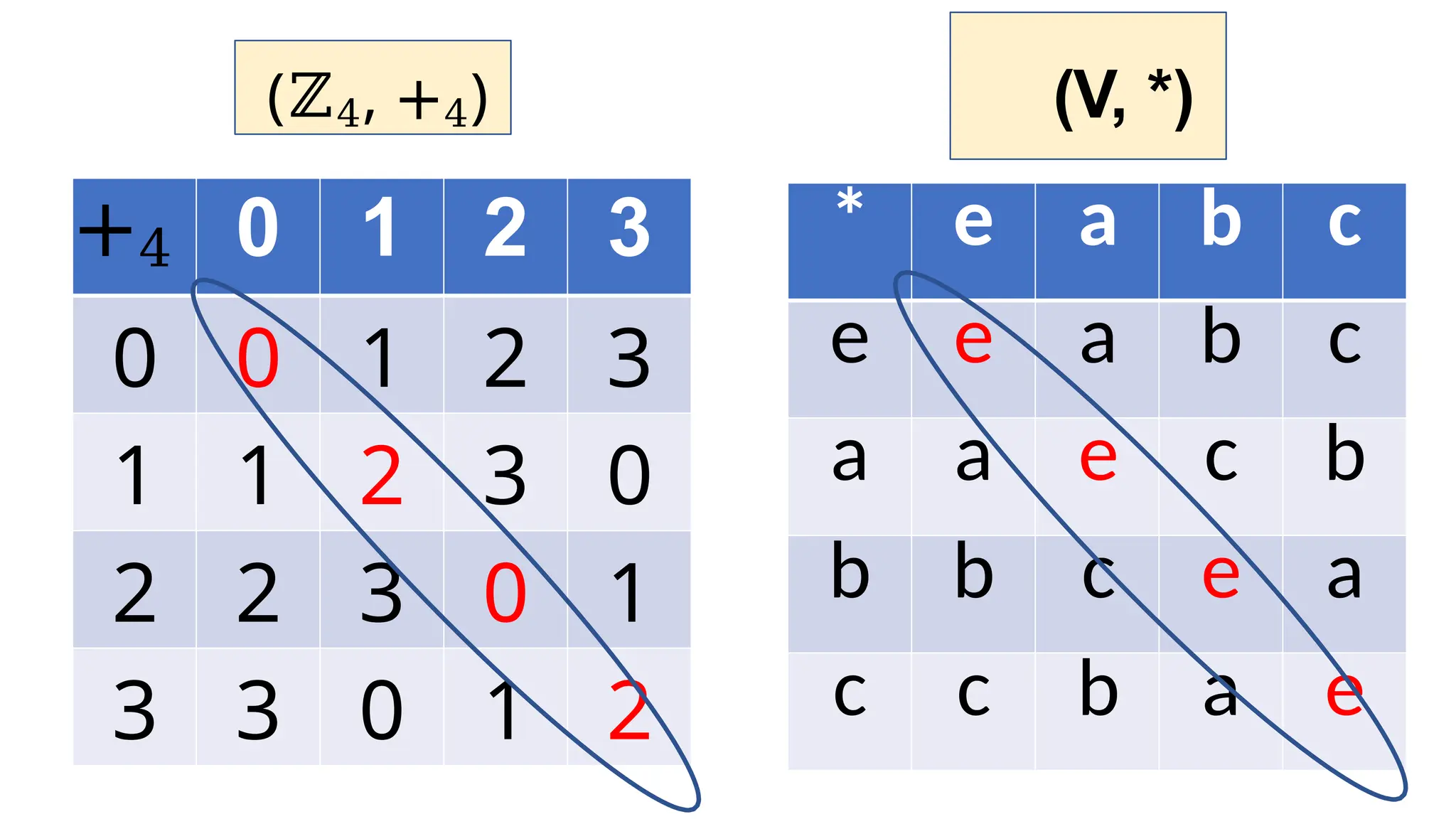

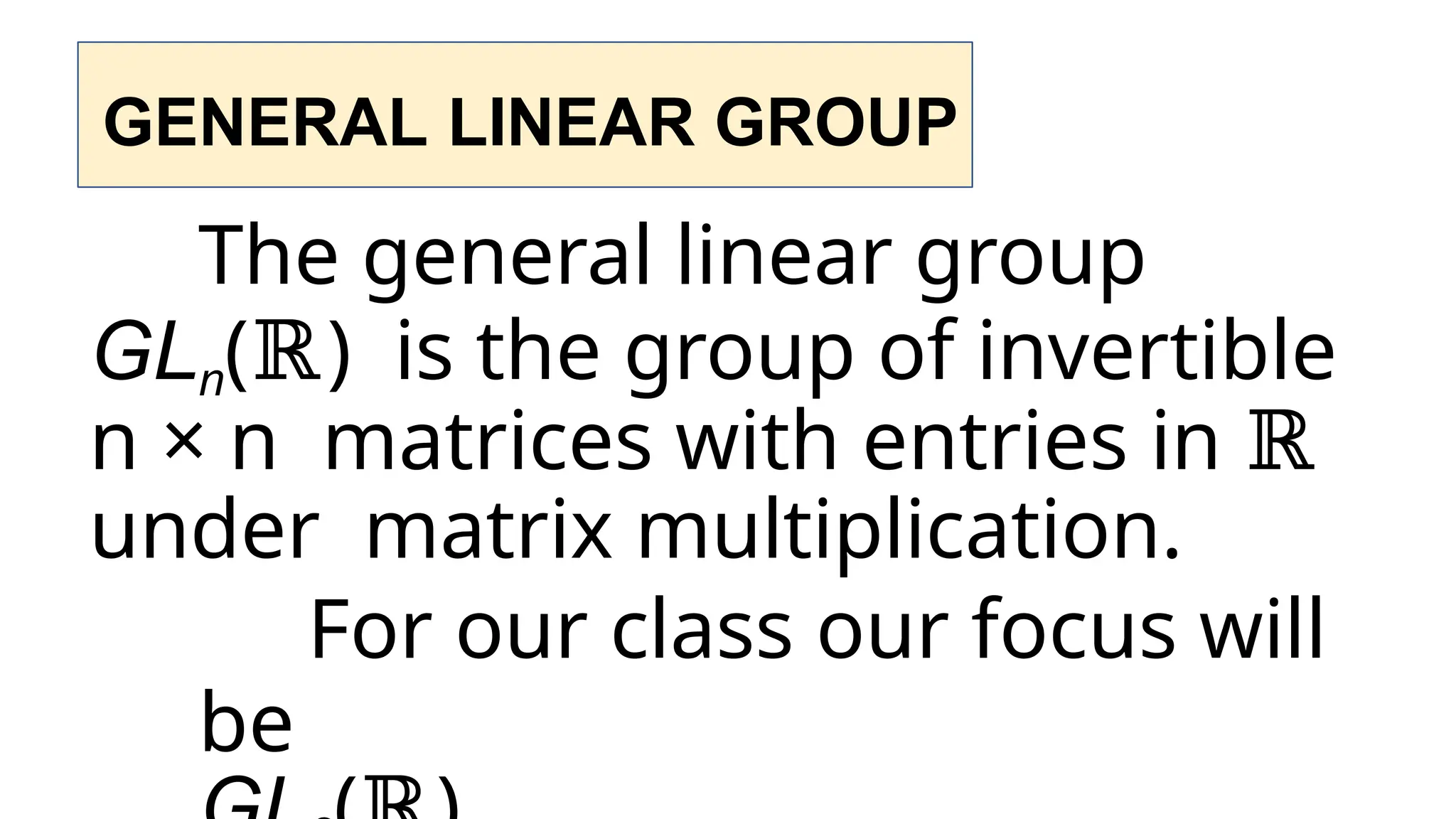

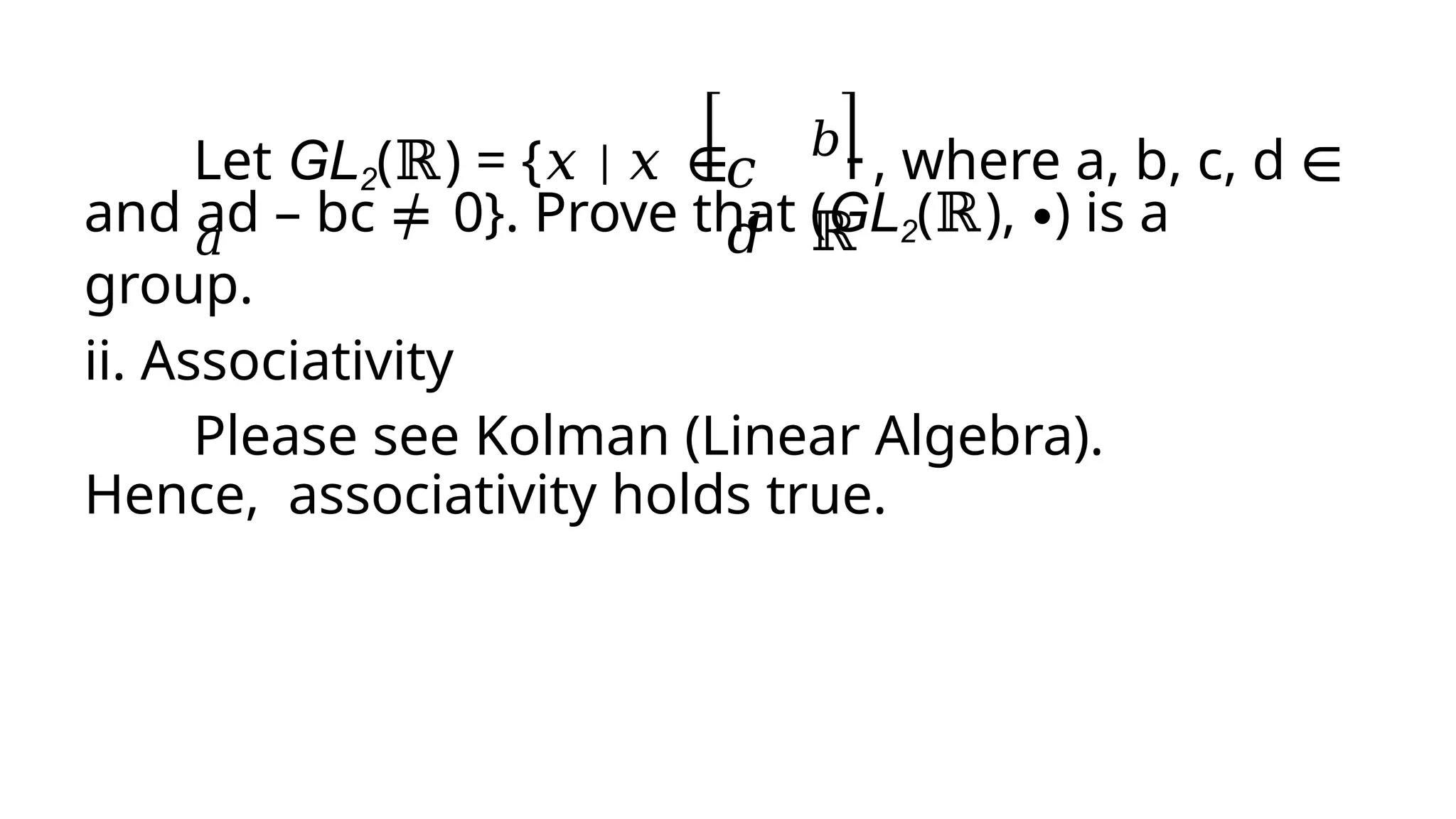

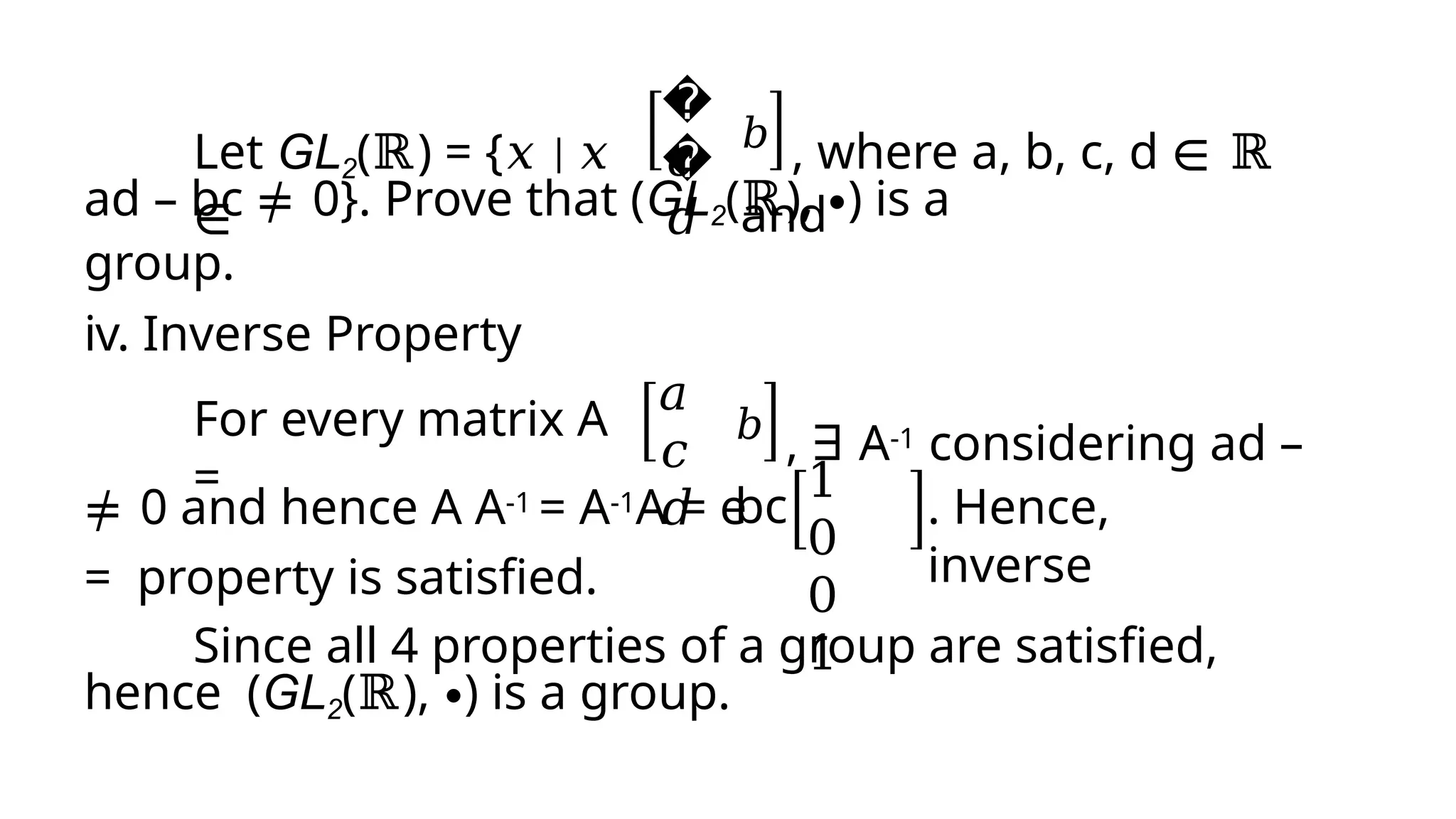

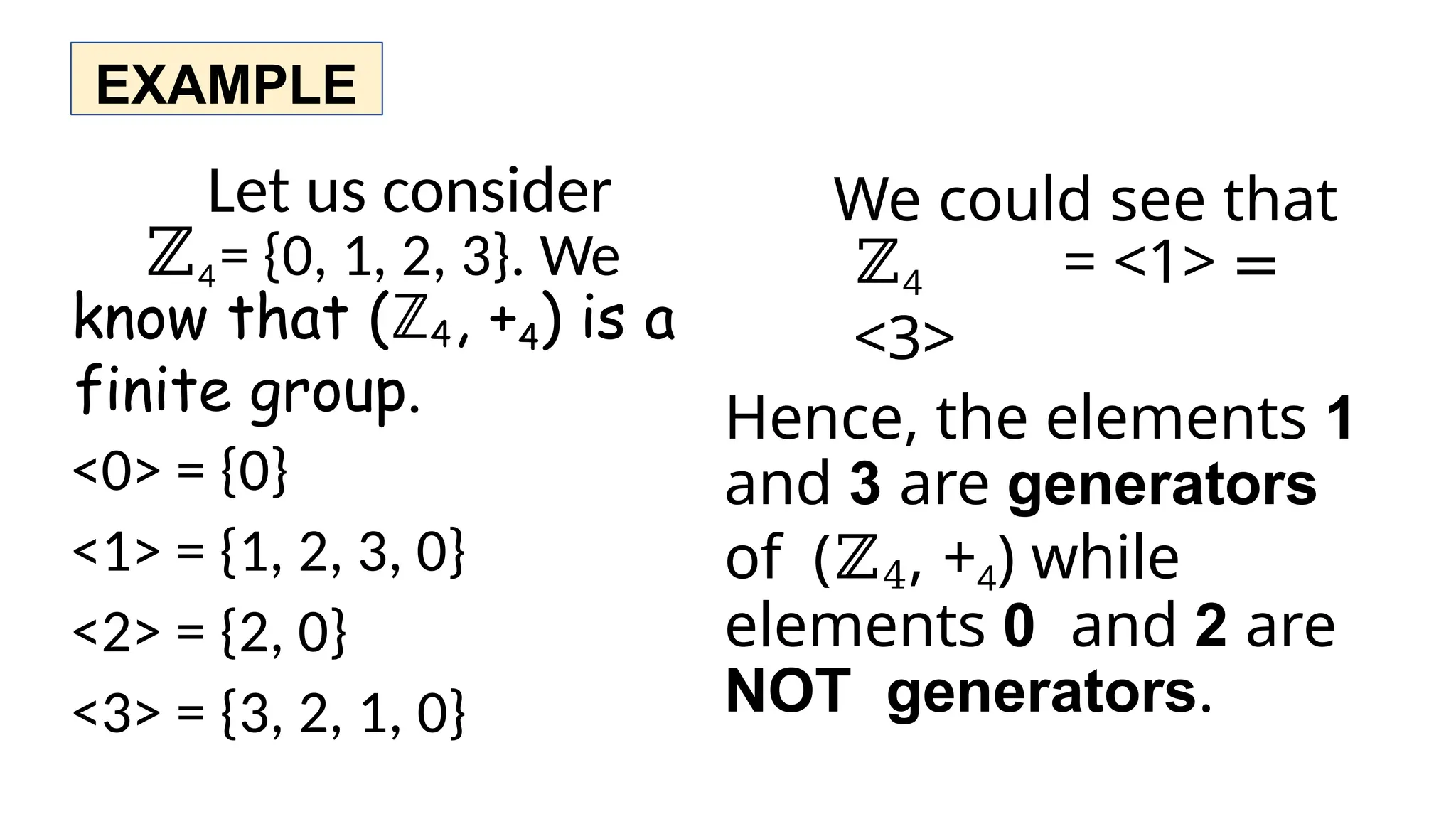

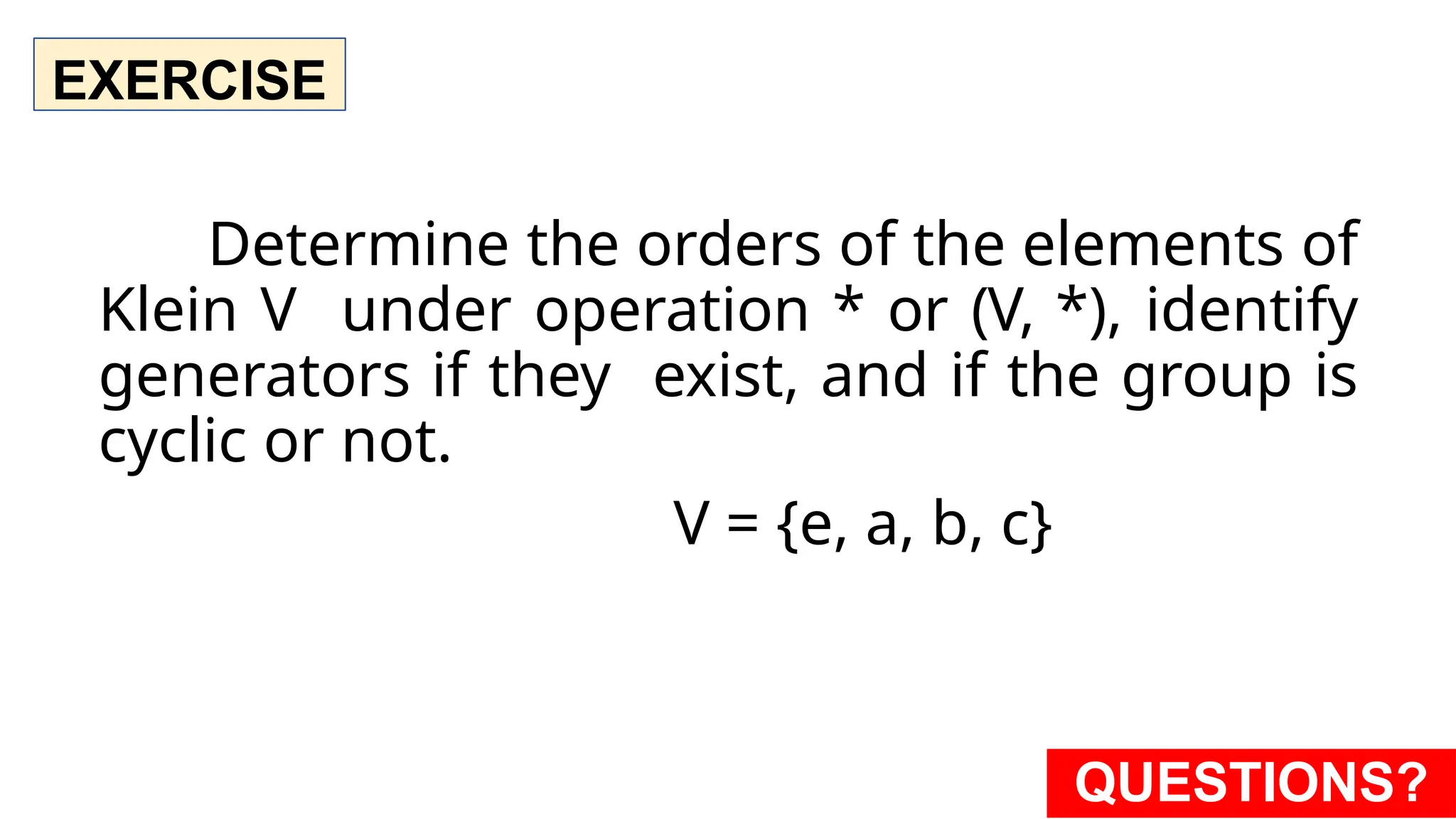

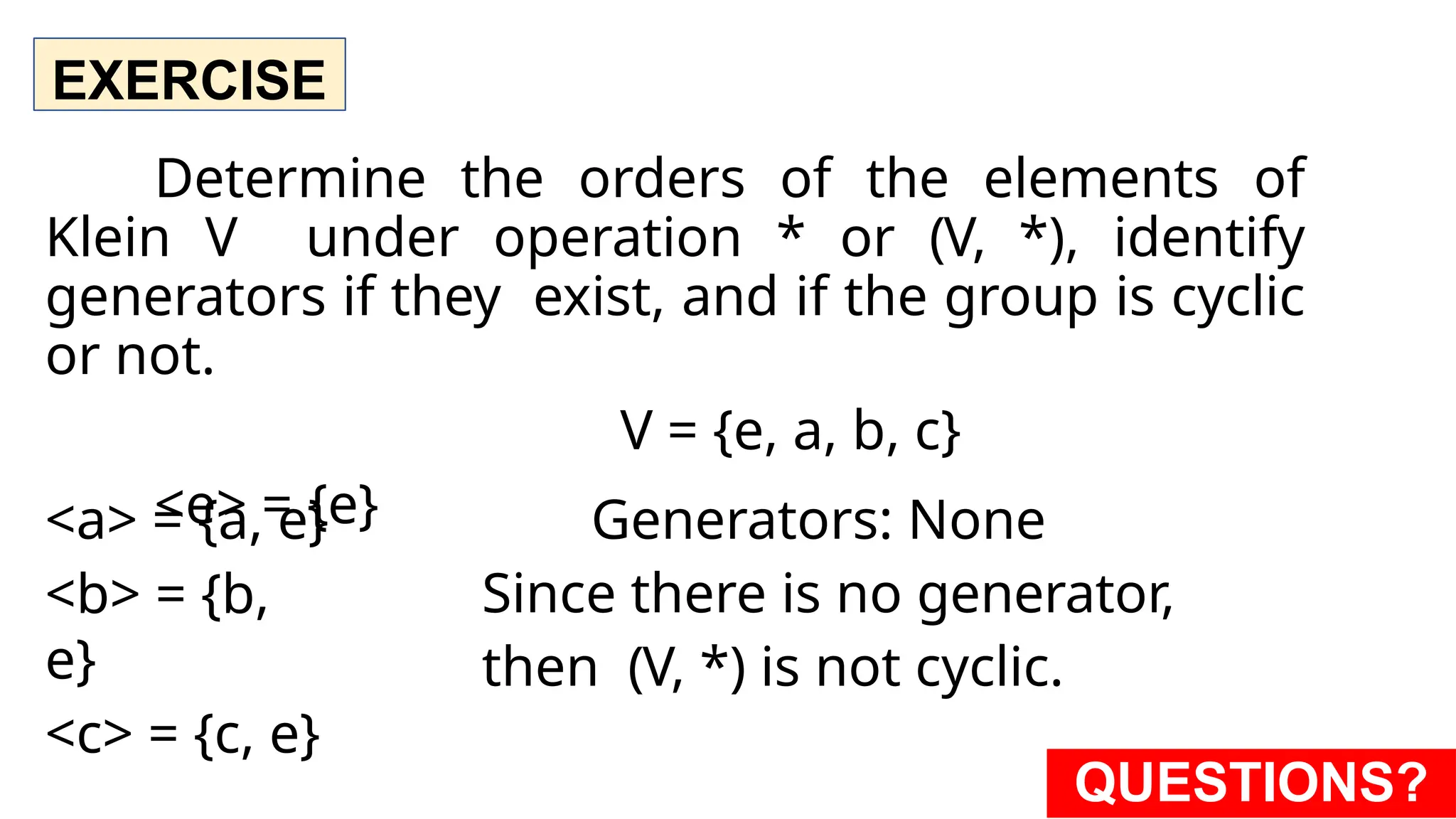

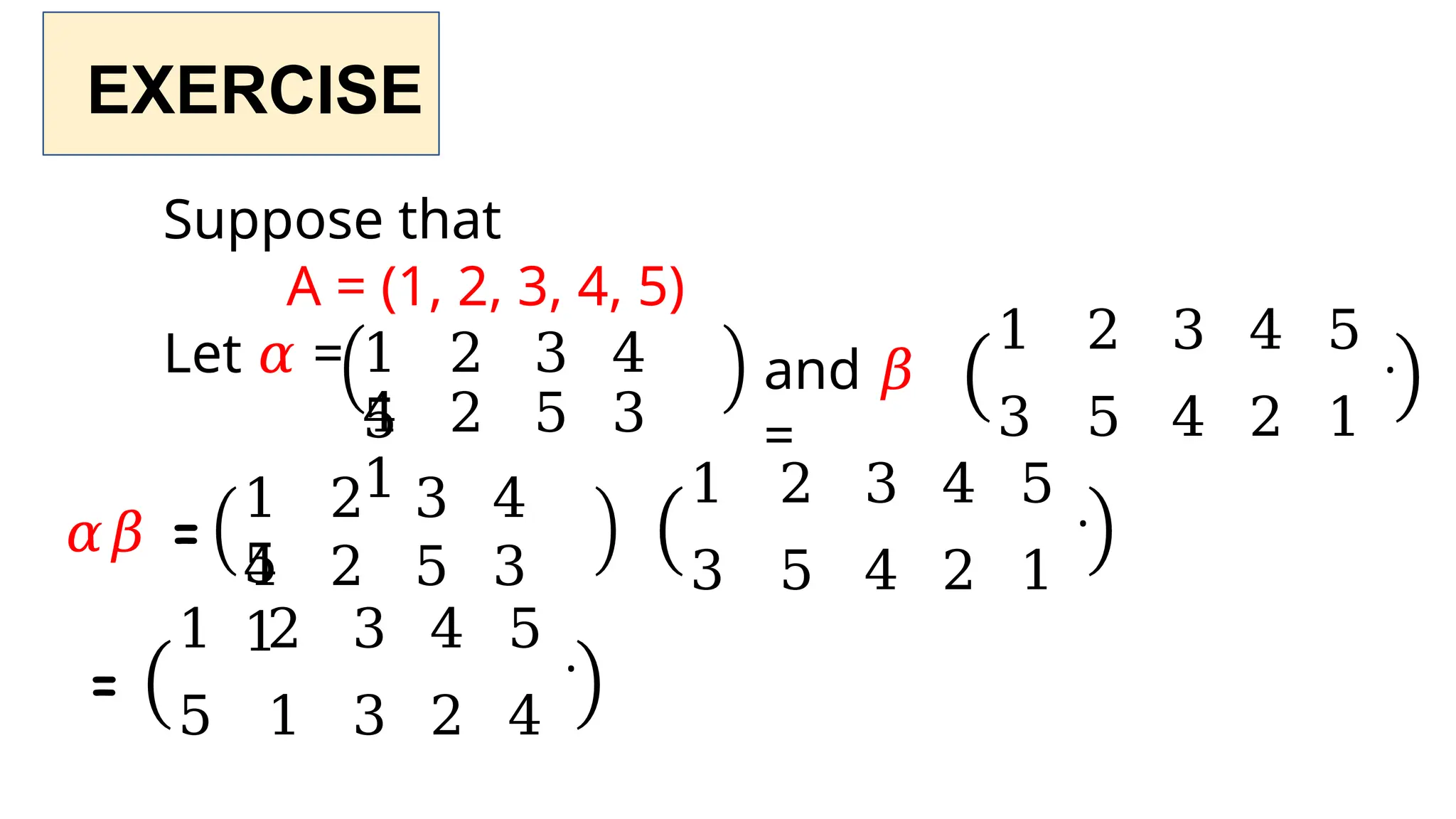

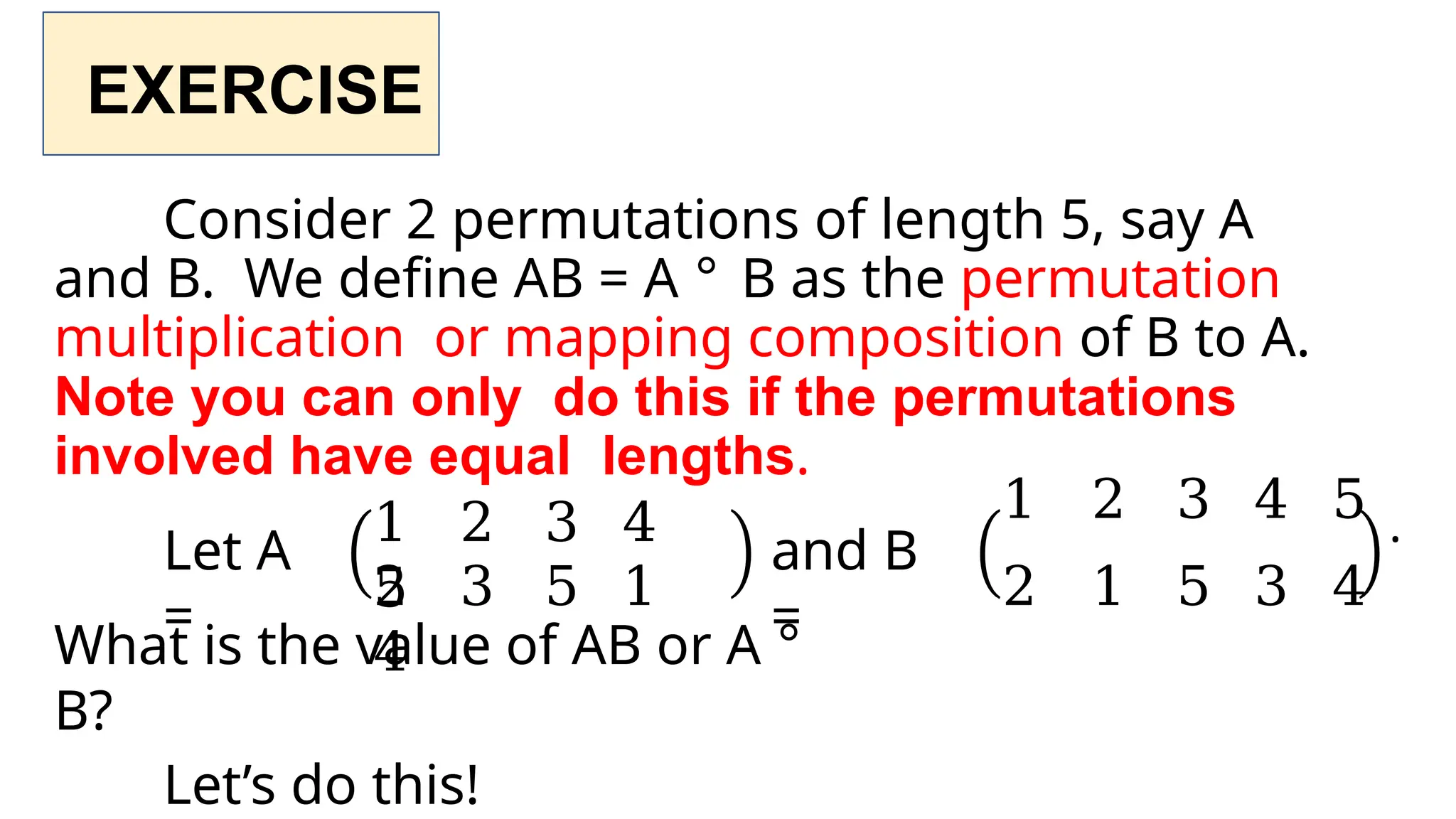

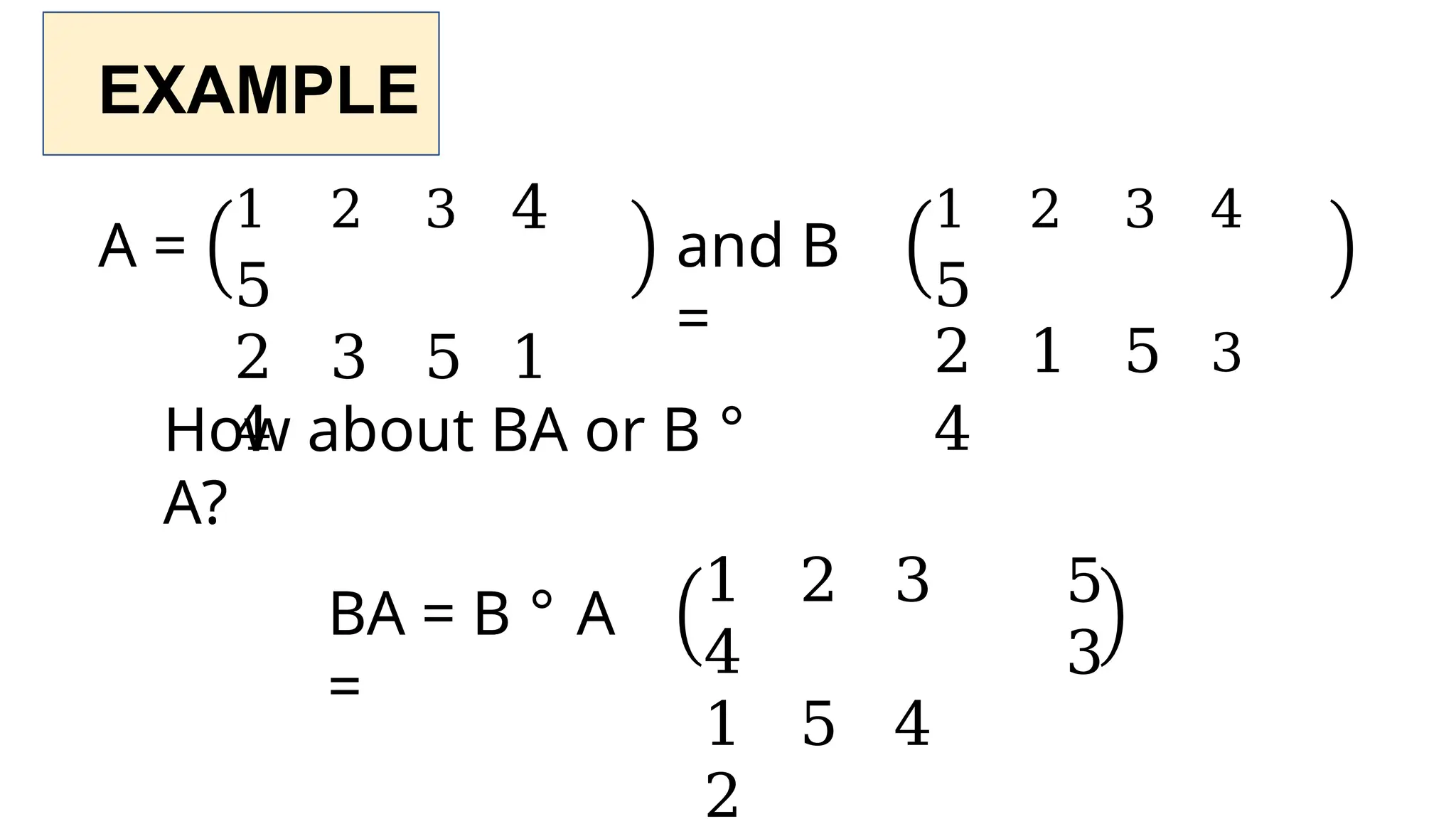

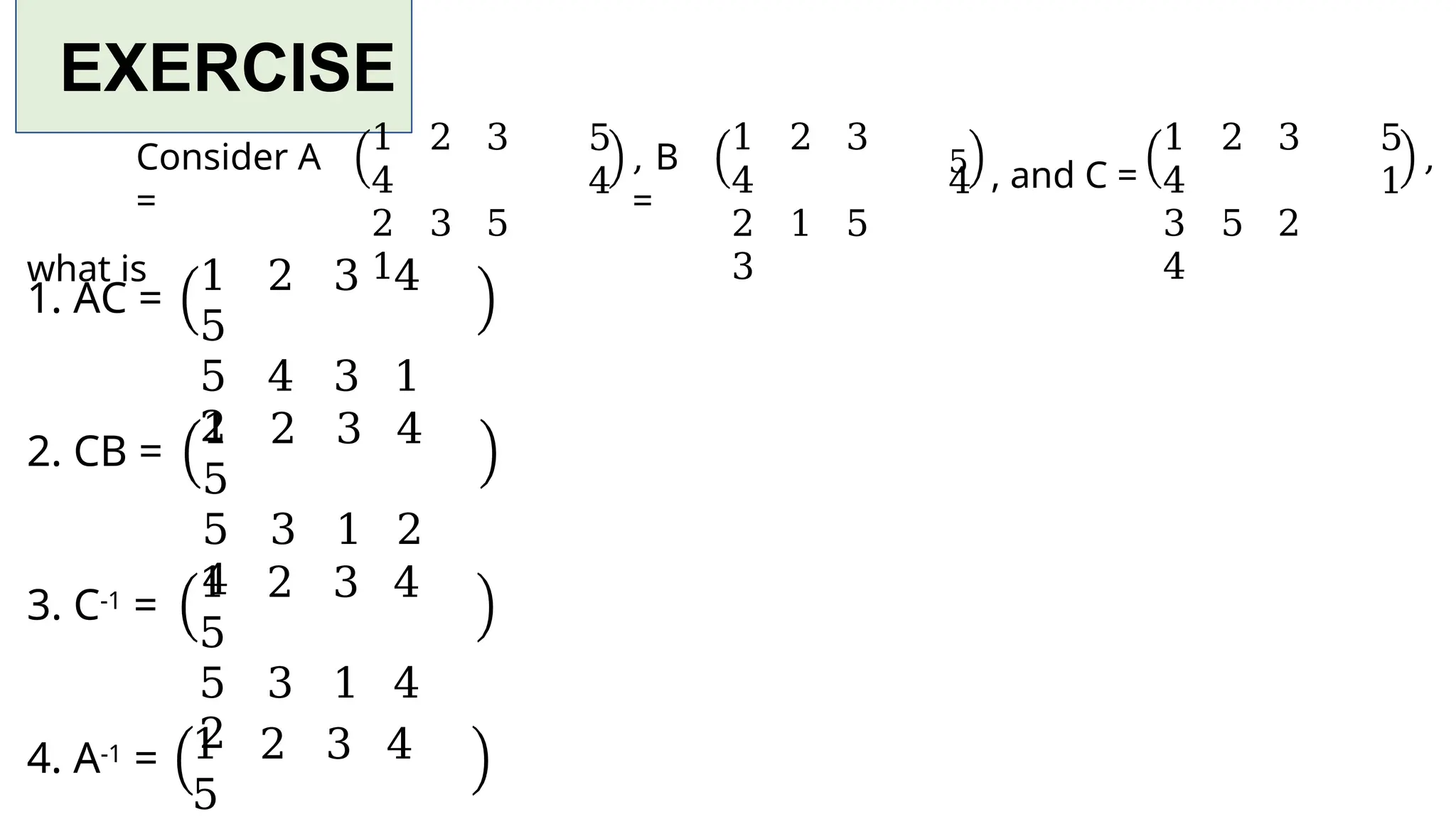

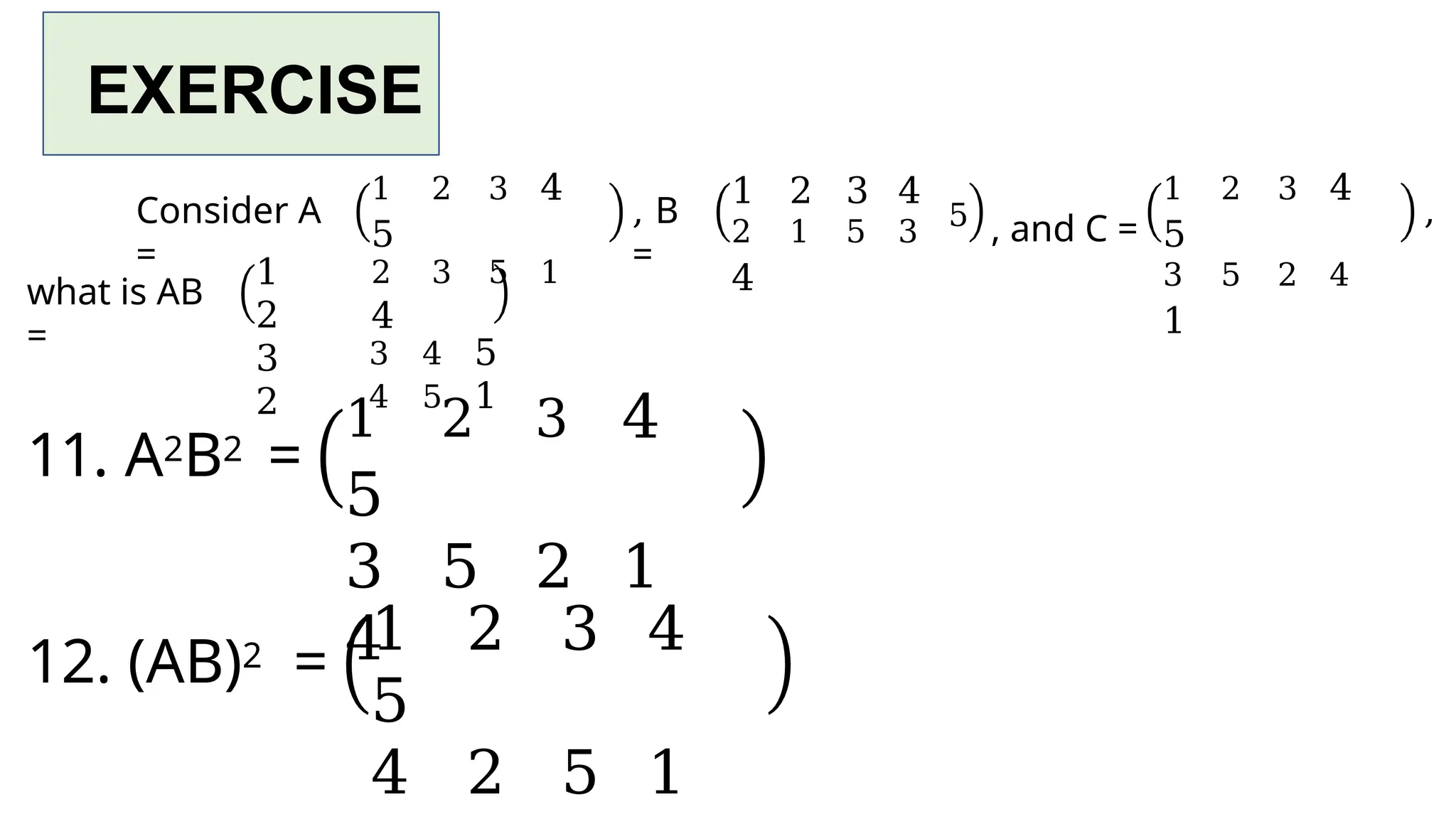

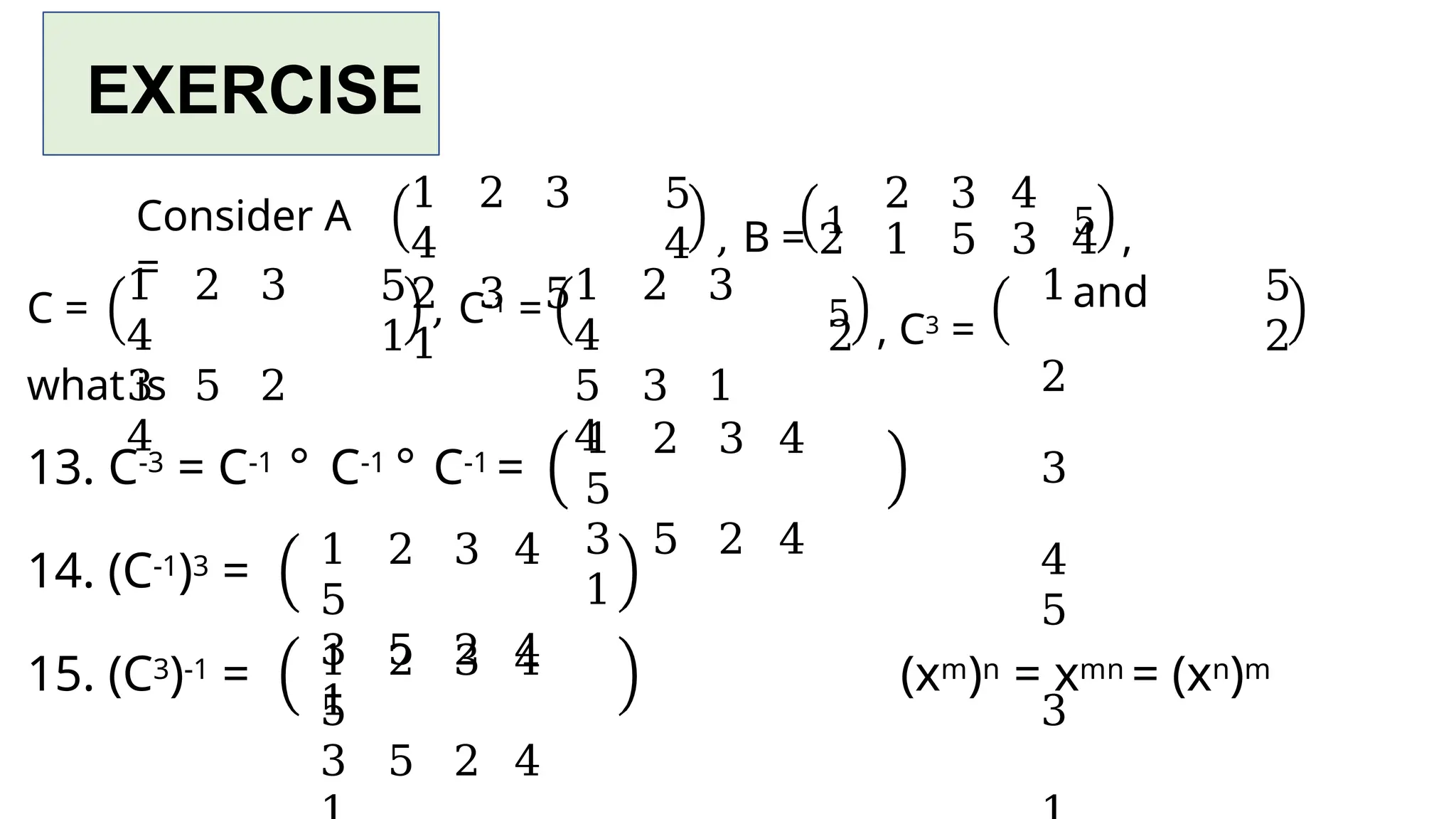

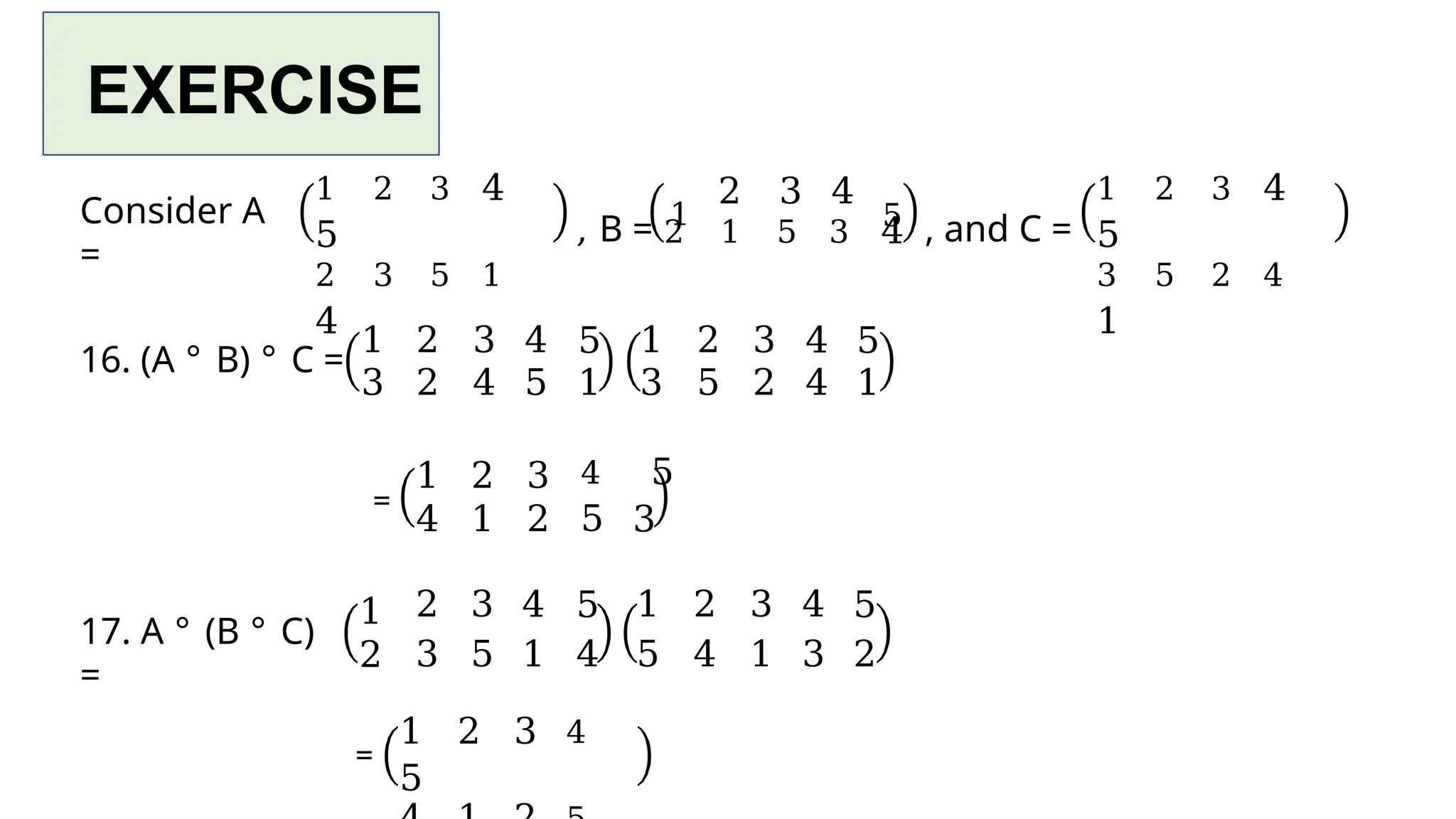

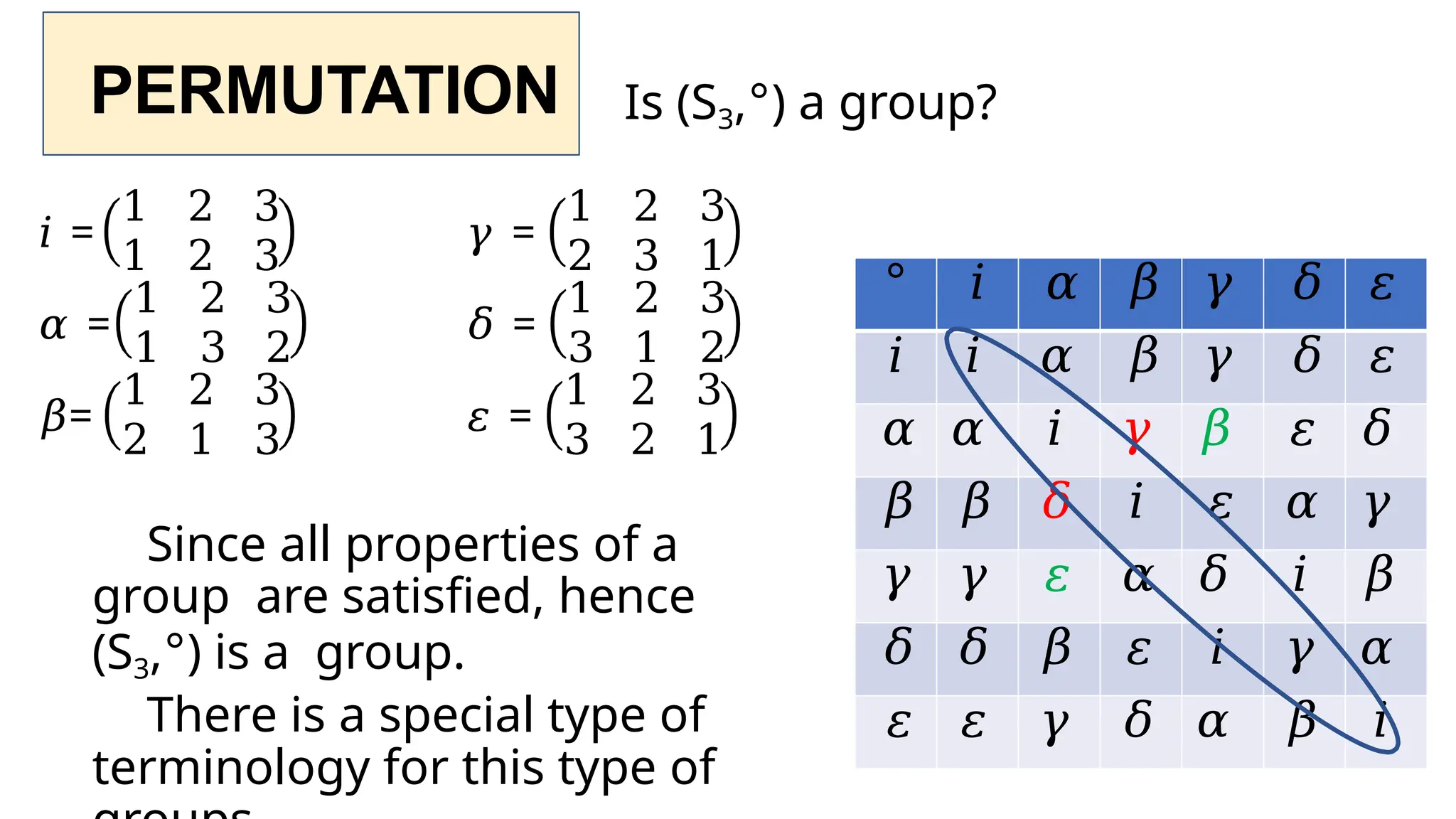

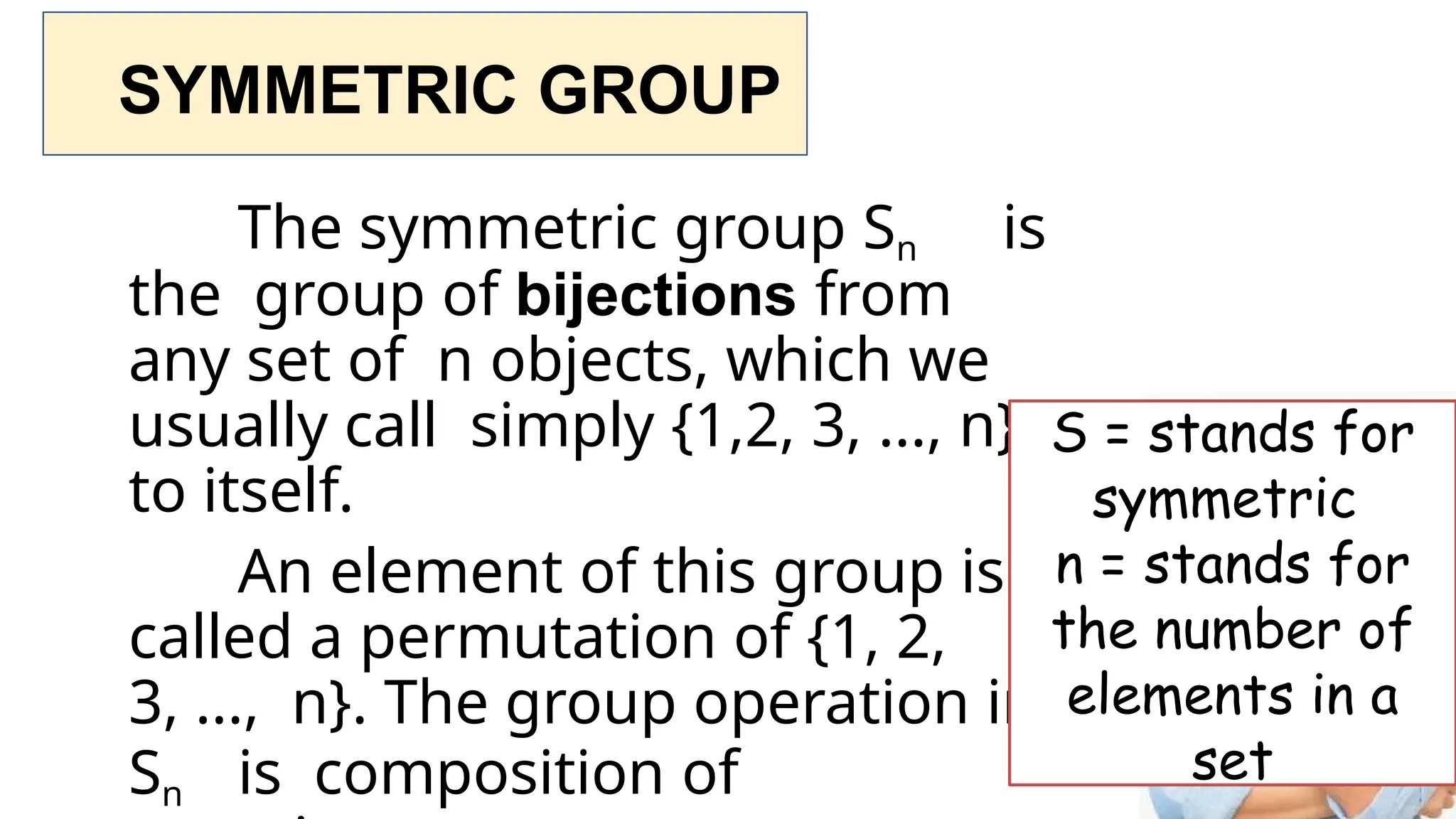

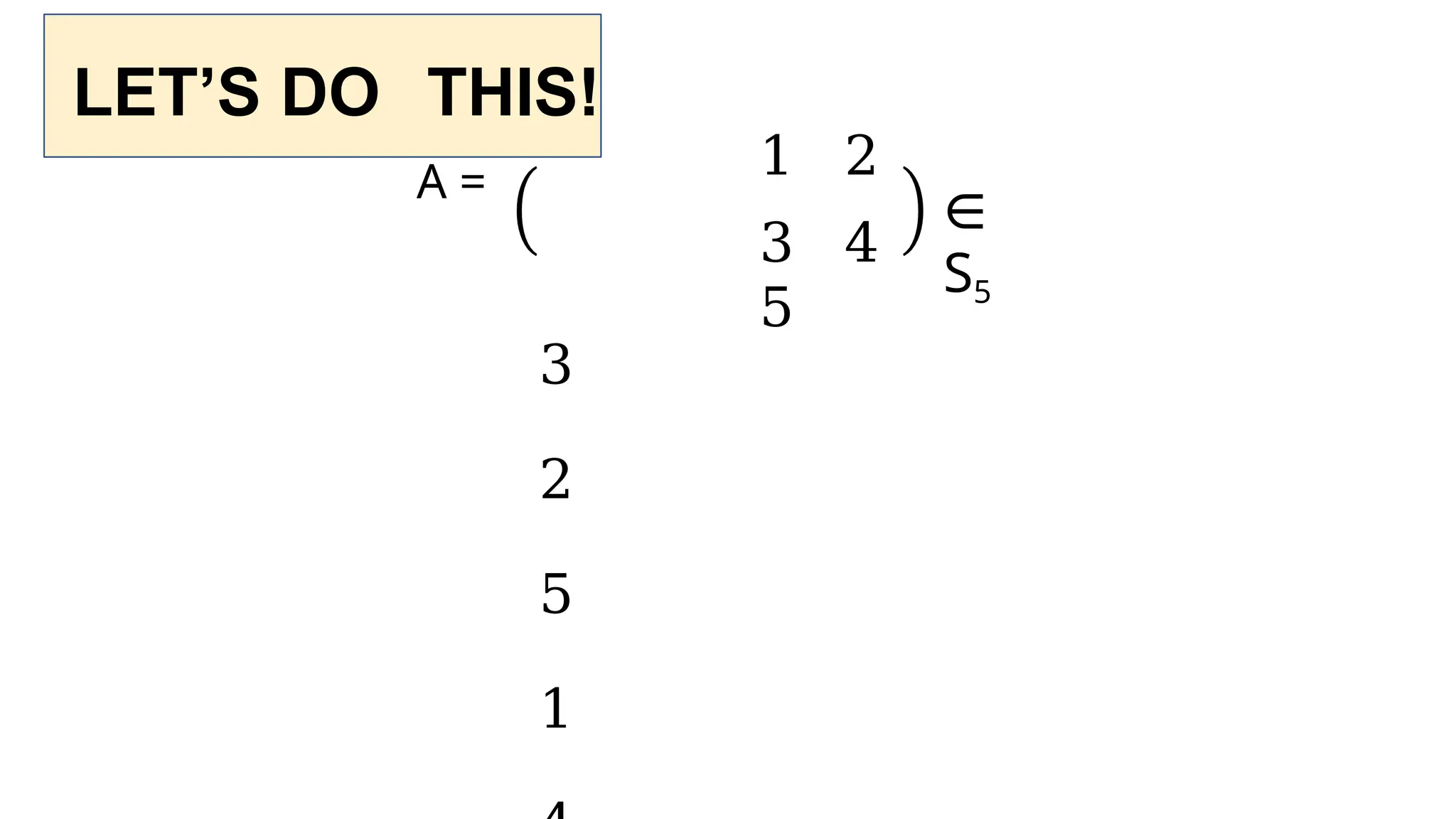

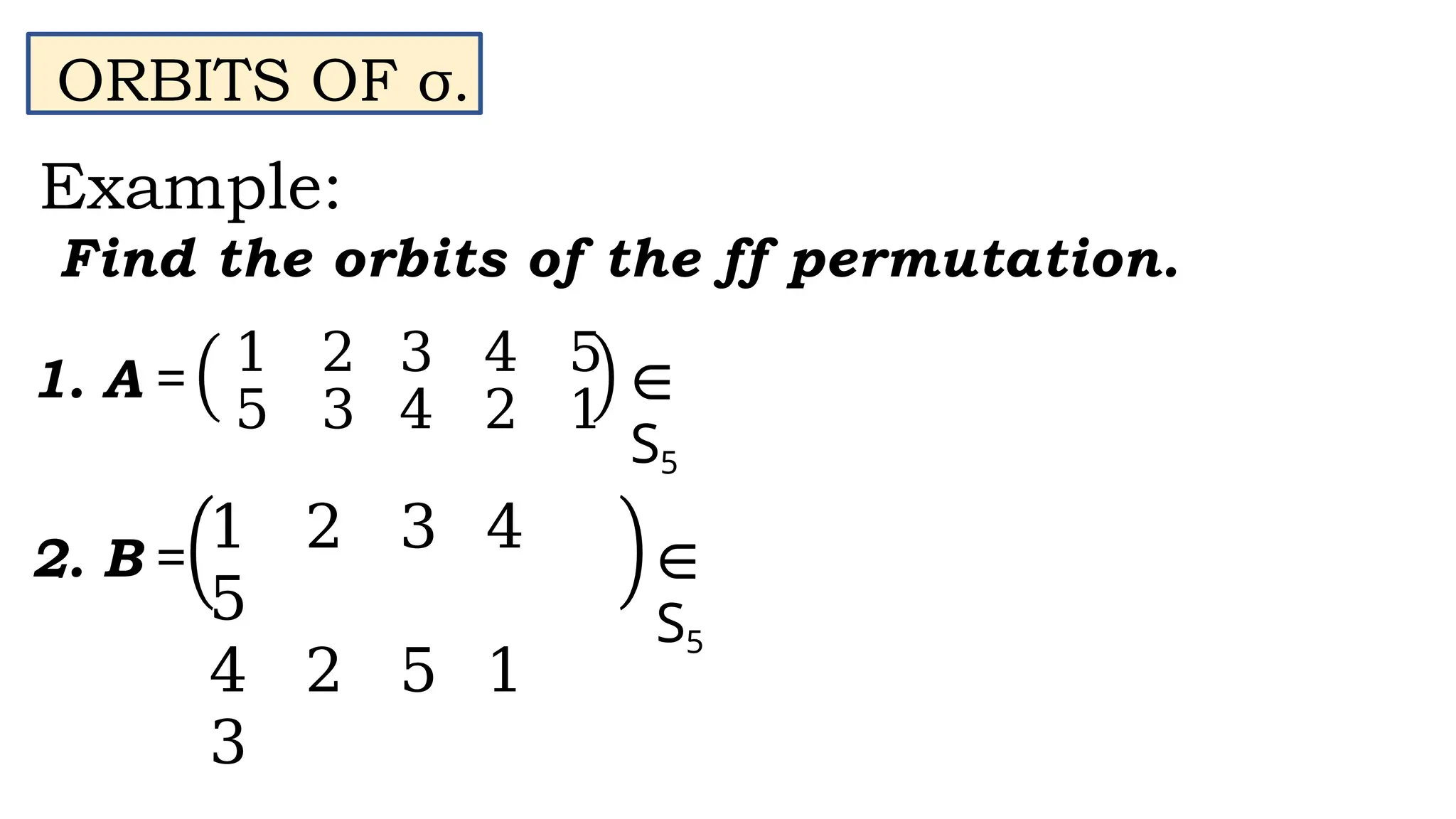

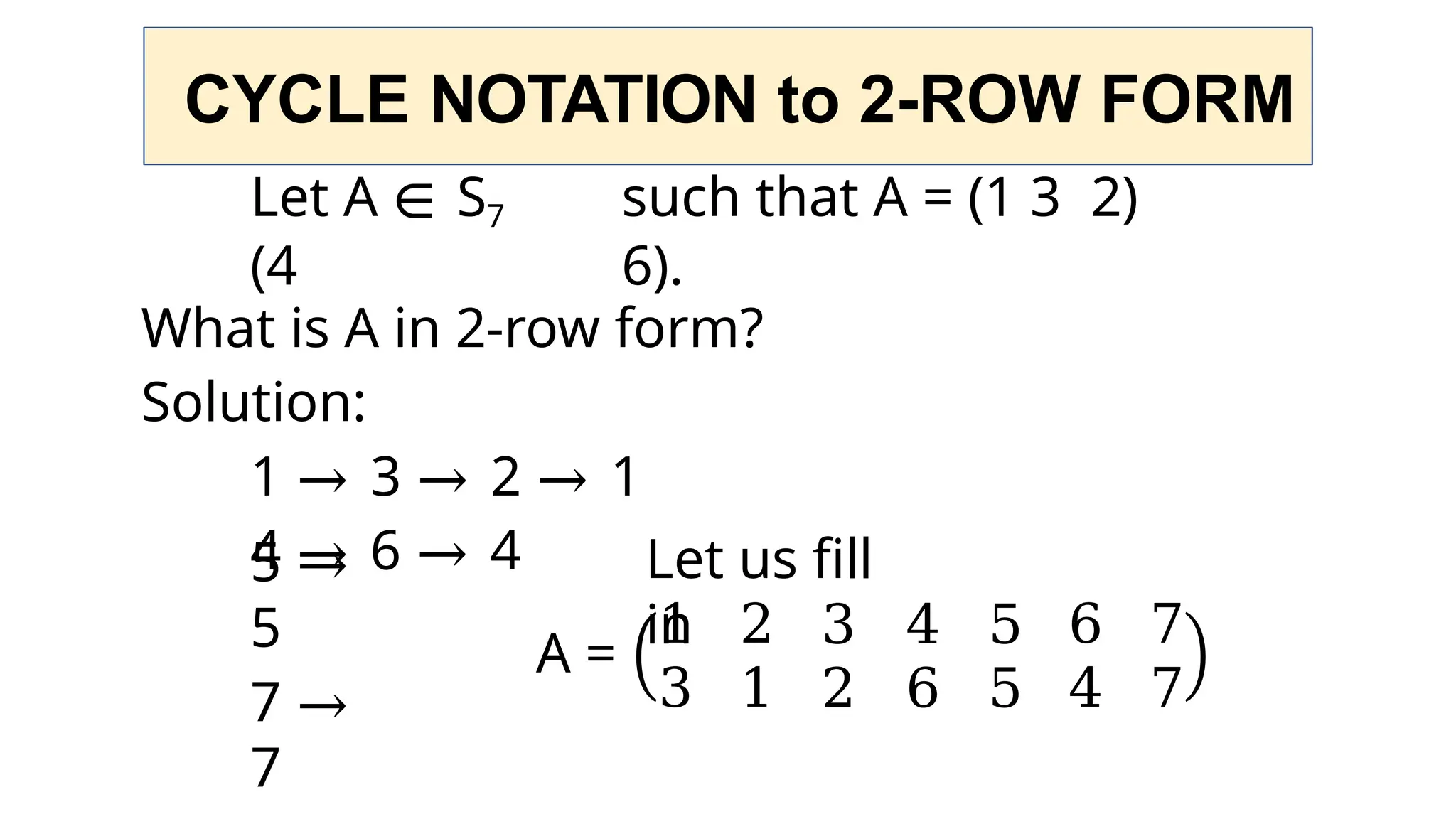

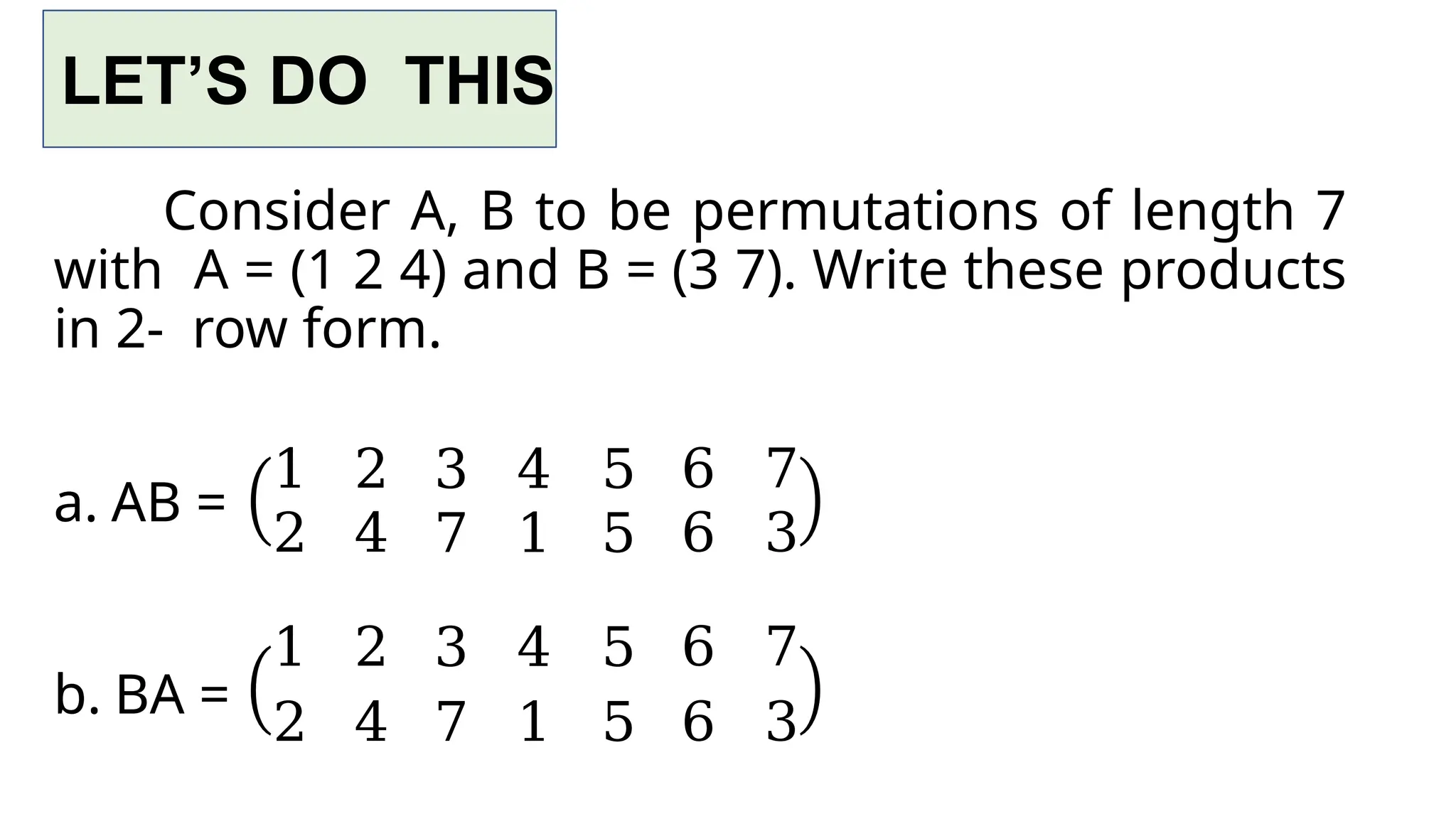

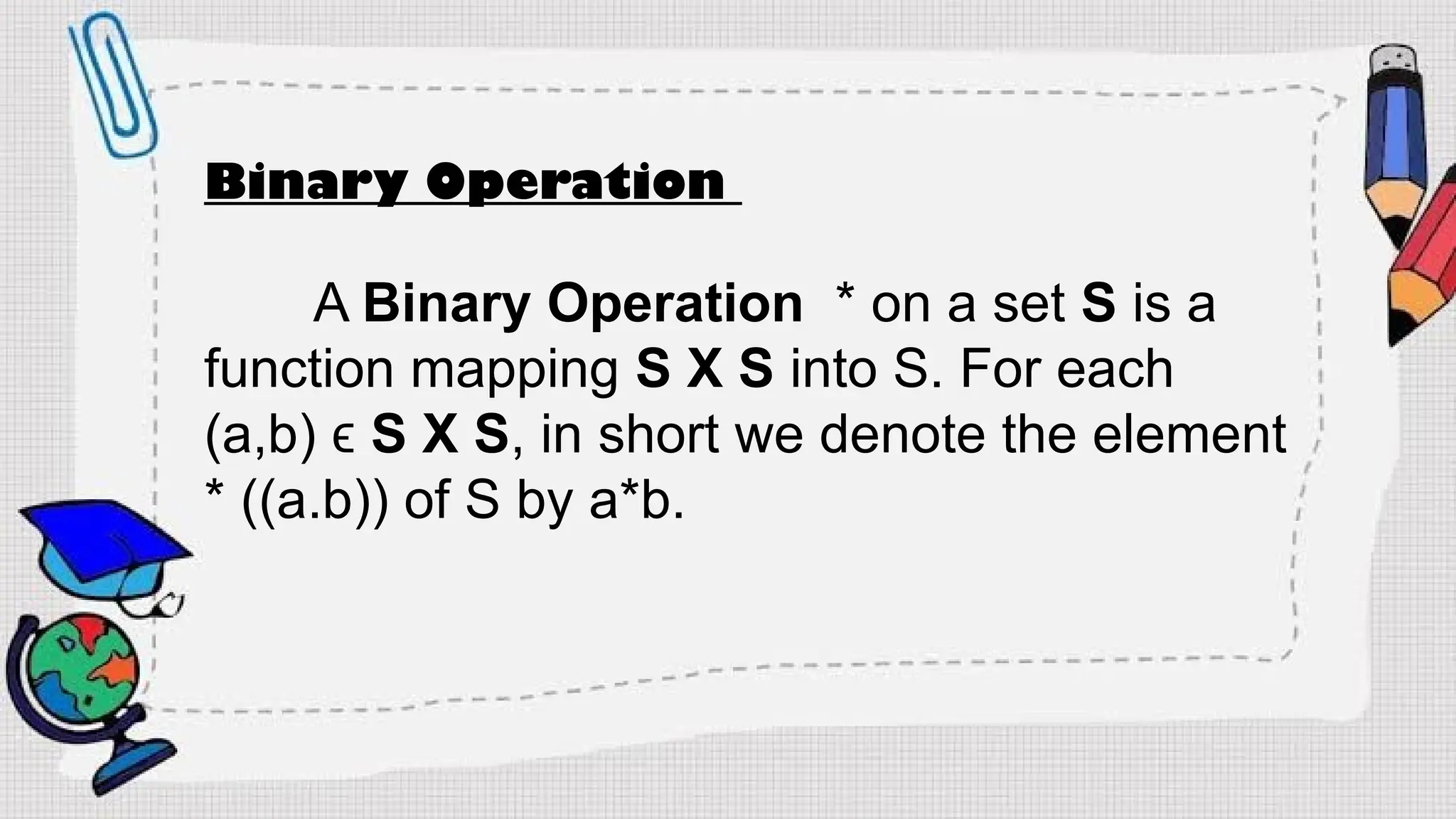

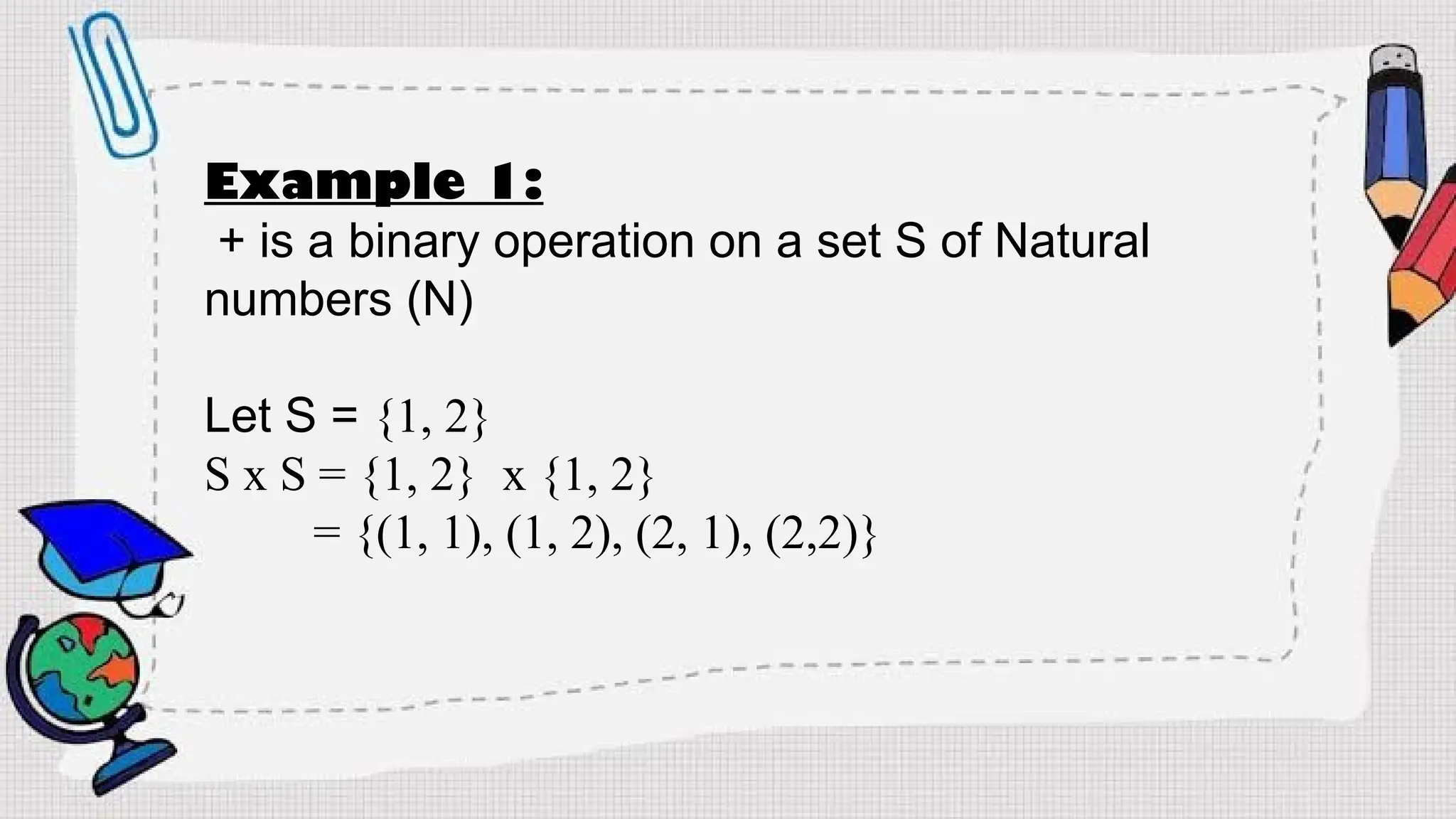

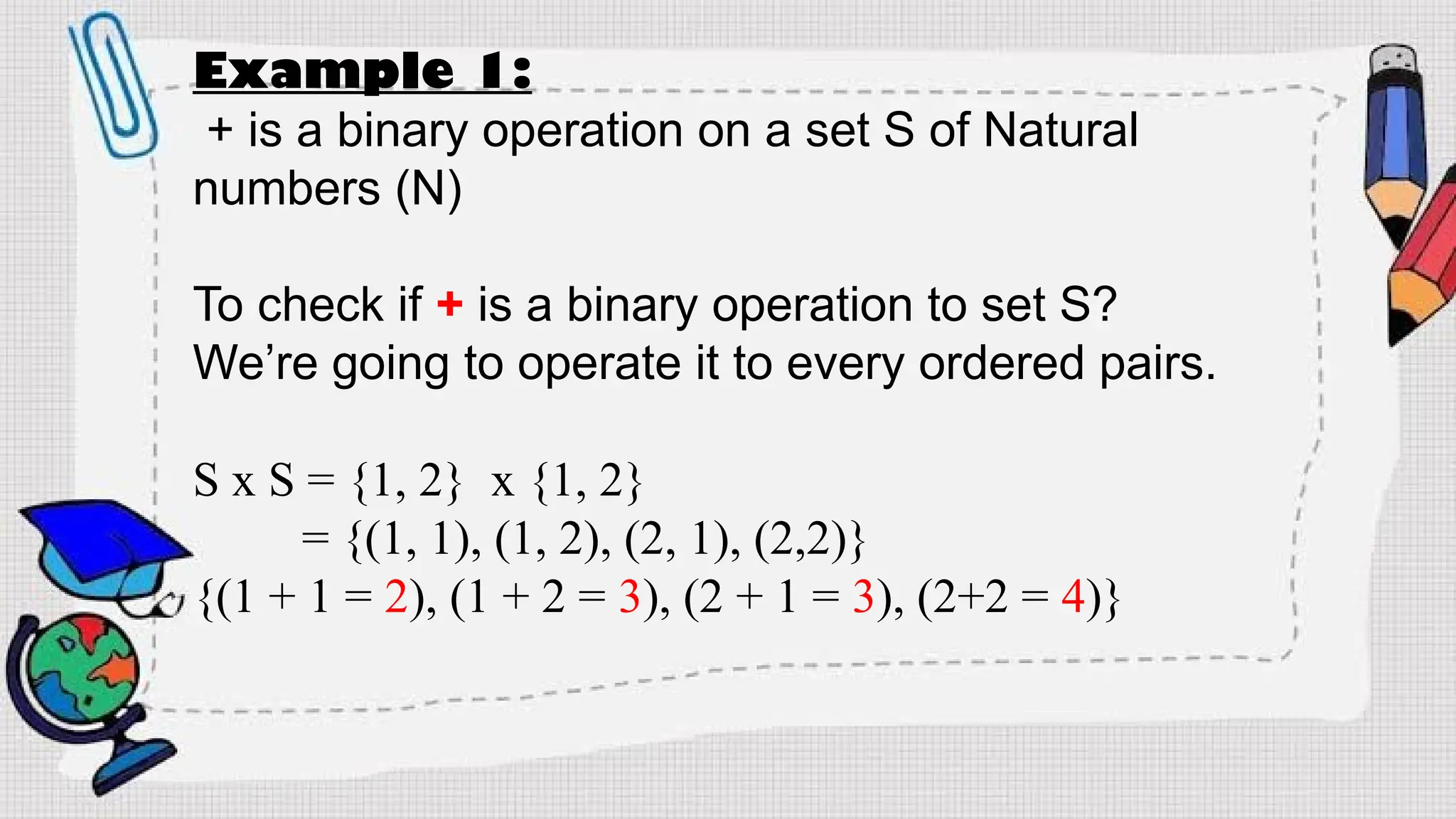

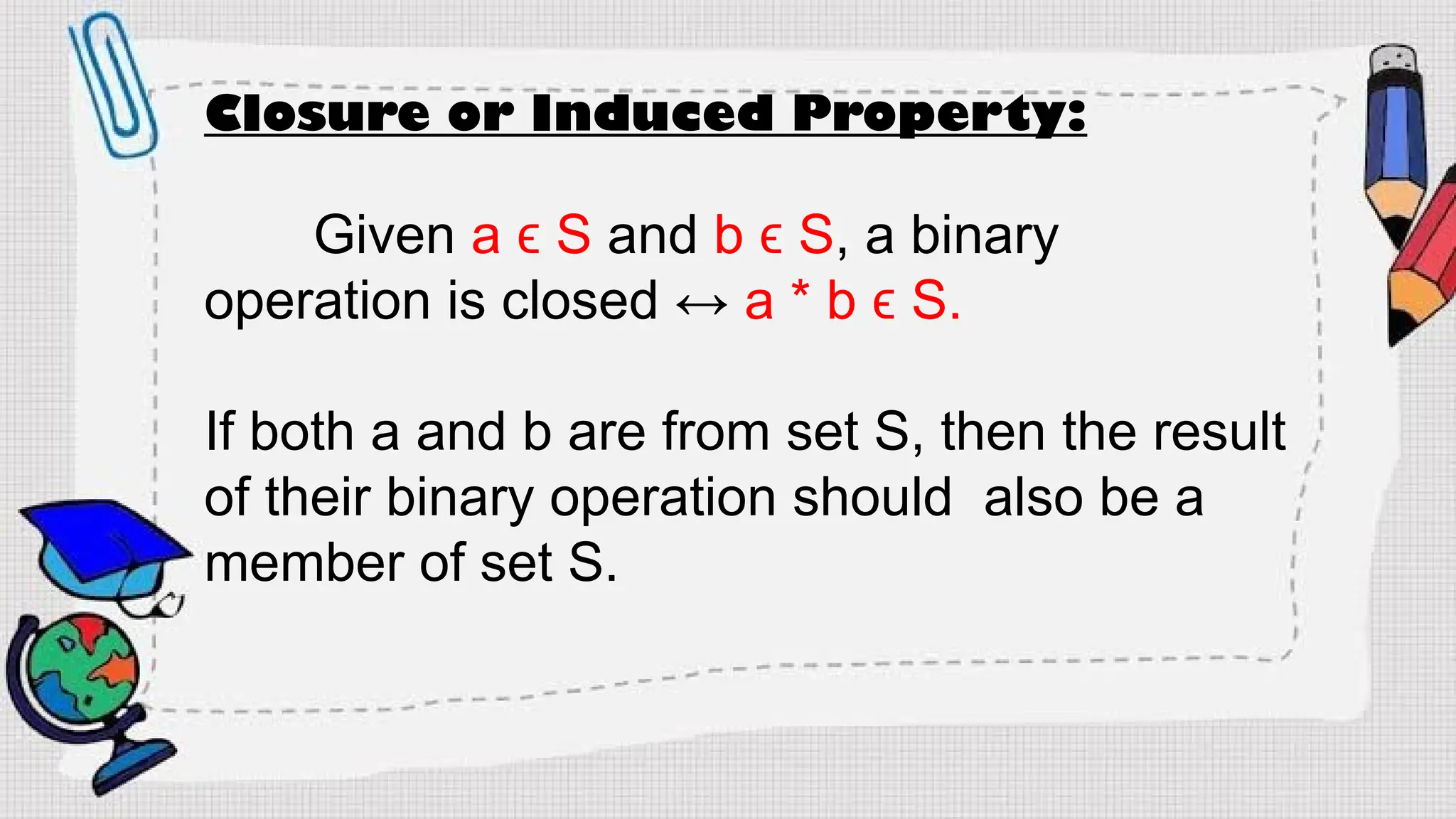

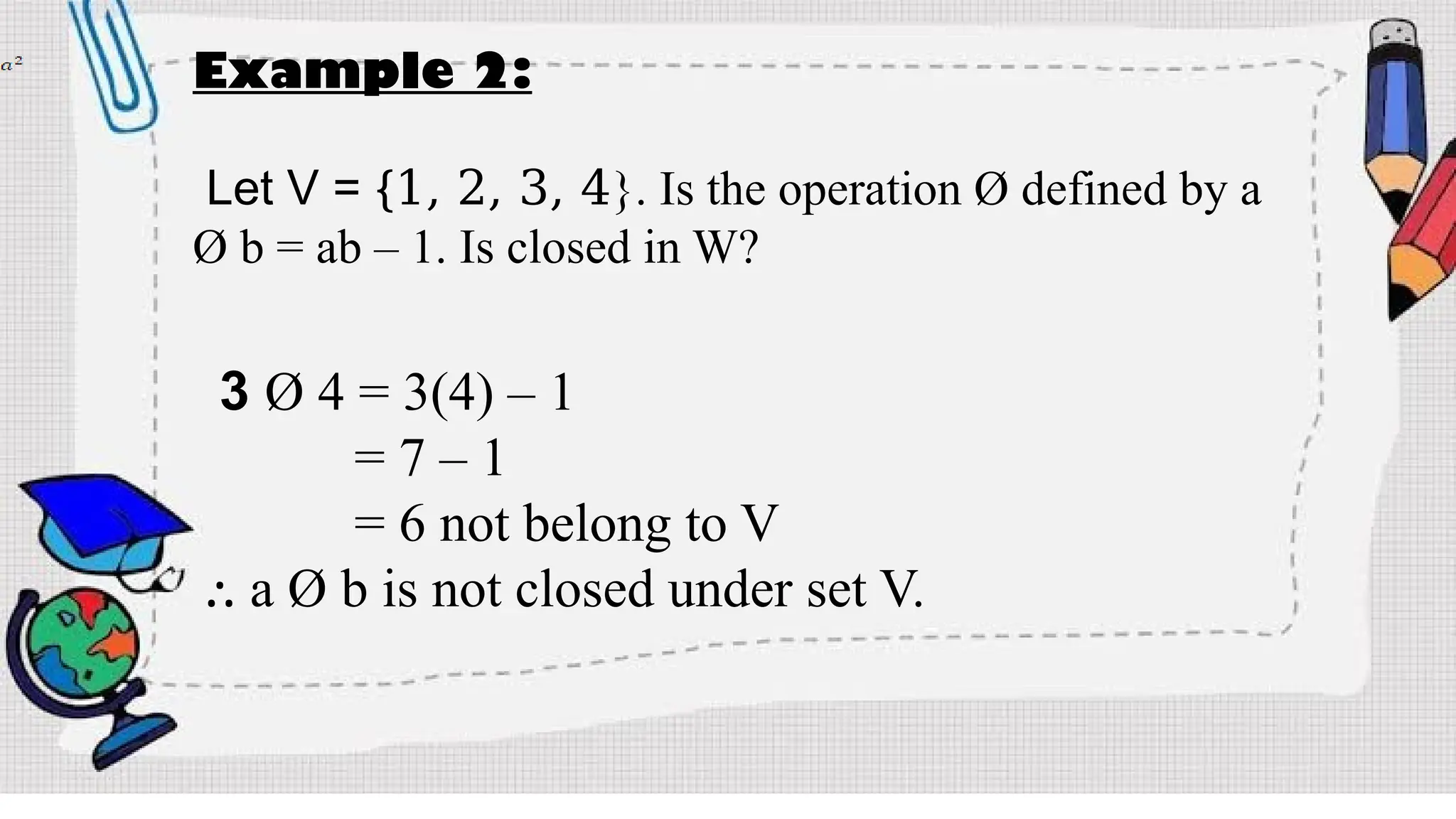

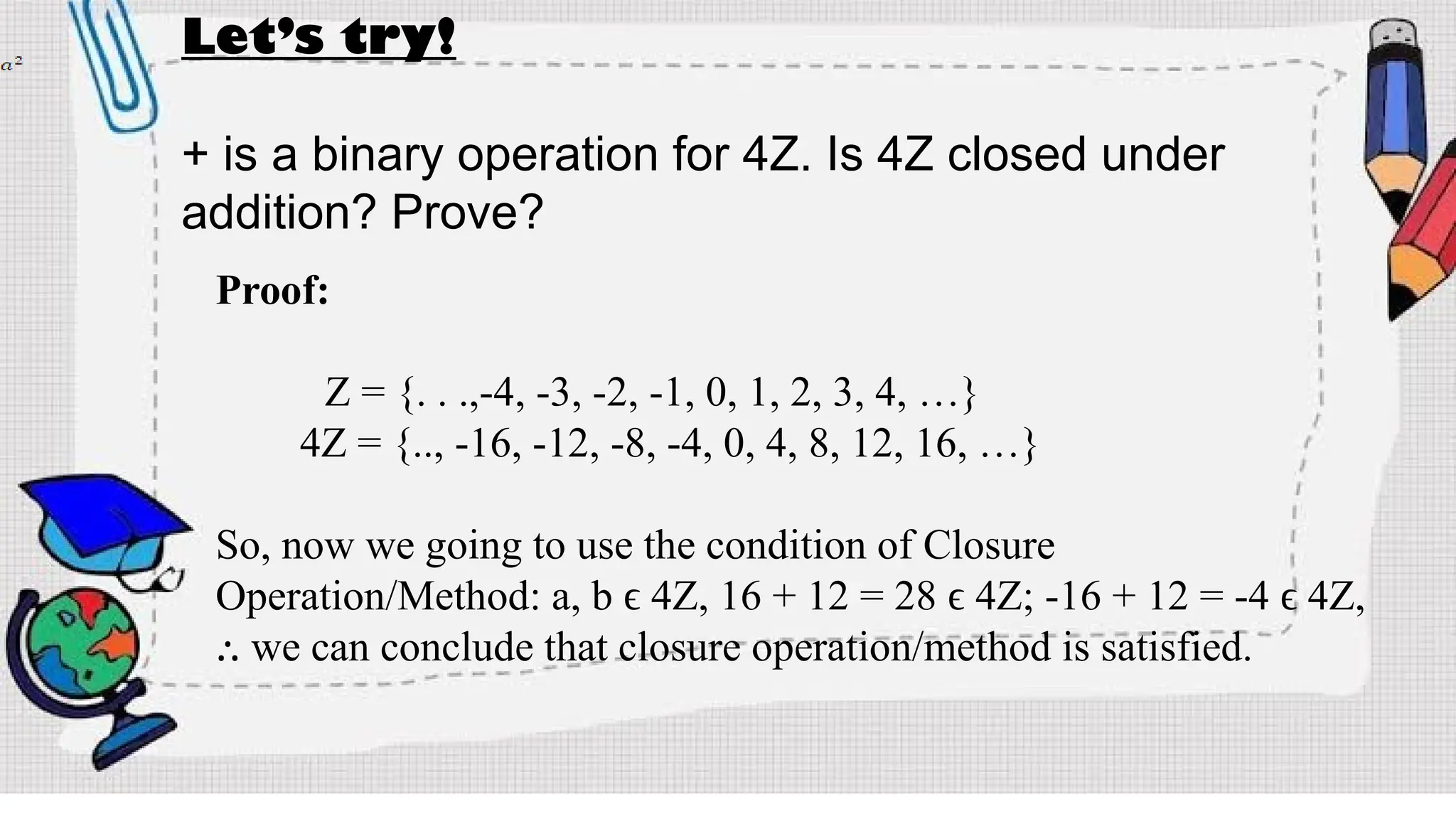

The document discusses binary operations defined on sets, outlining properties such as closure, associativity, identity, and inverse in the context of groups. It provides examples with natural numbers and real numbers to illustrate binary operations and explores the concept of groups including finite and infinite orders. Additionally, it examines specific groups like the Klein group and general linear groups, validating their structure under different operations.

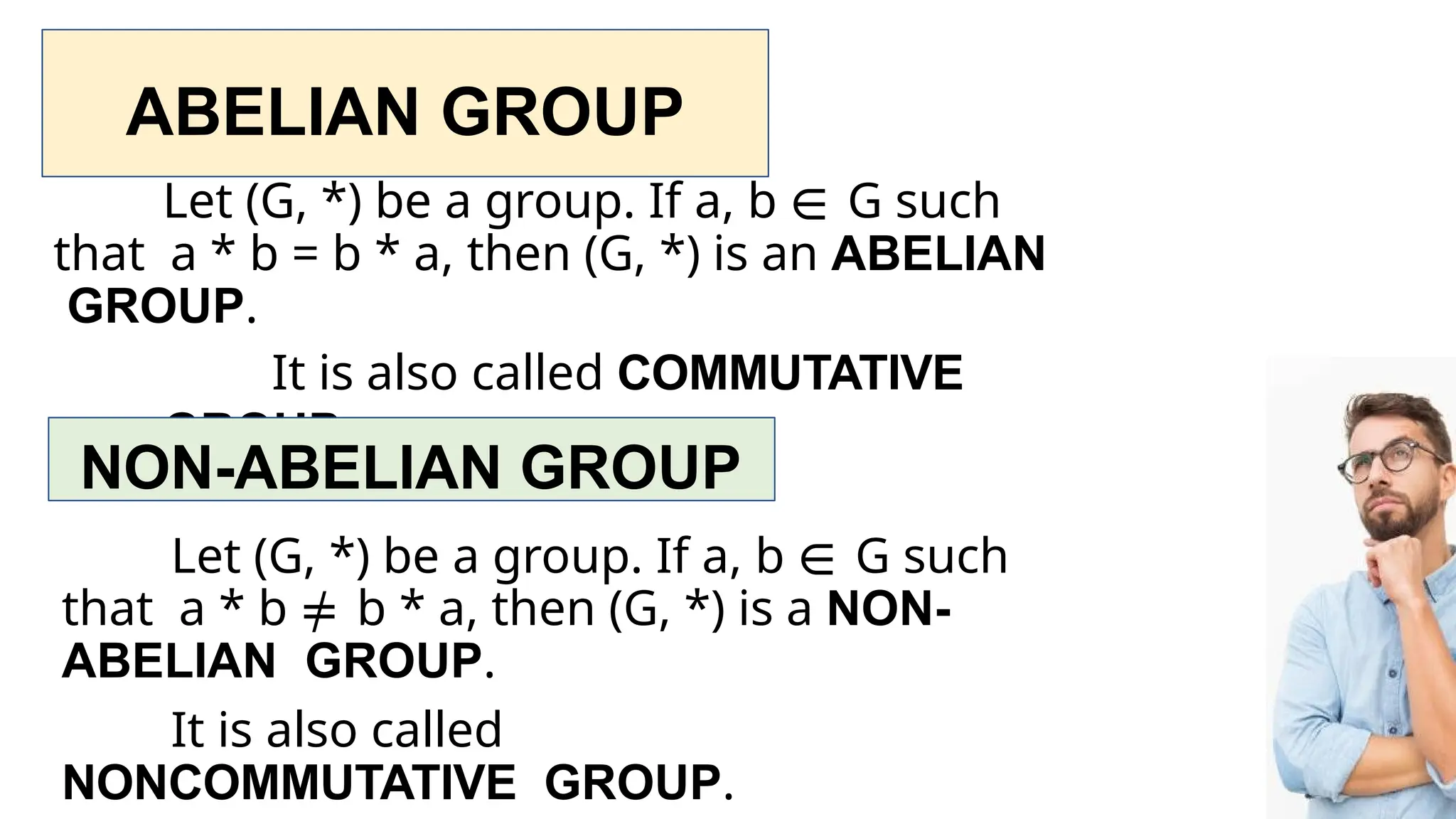

![Example 1:

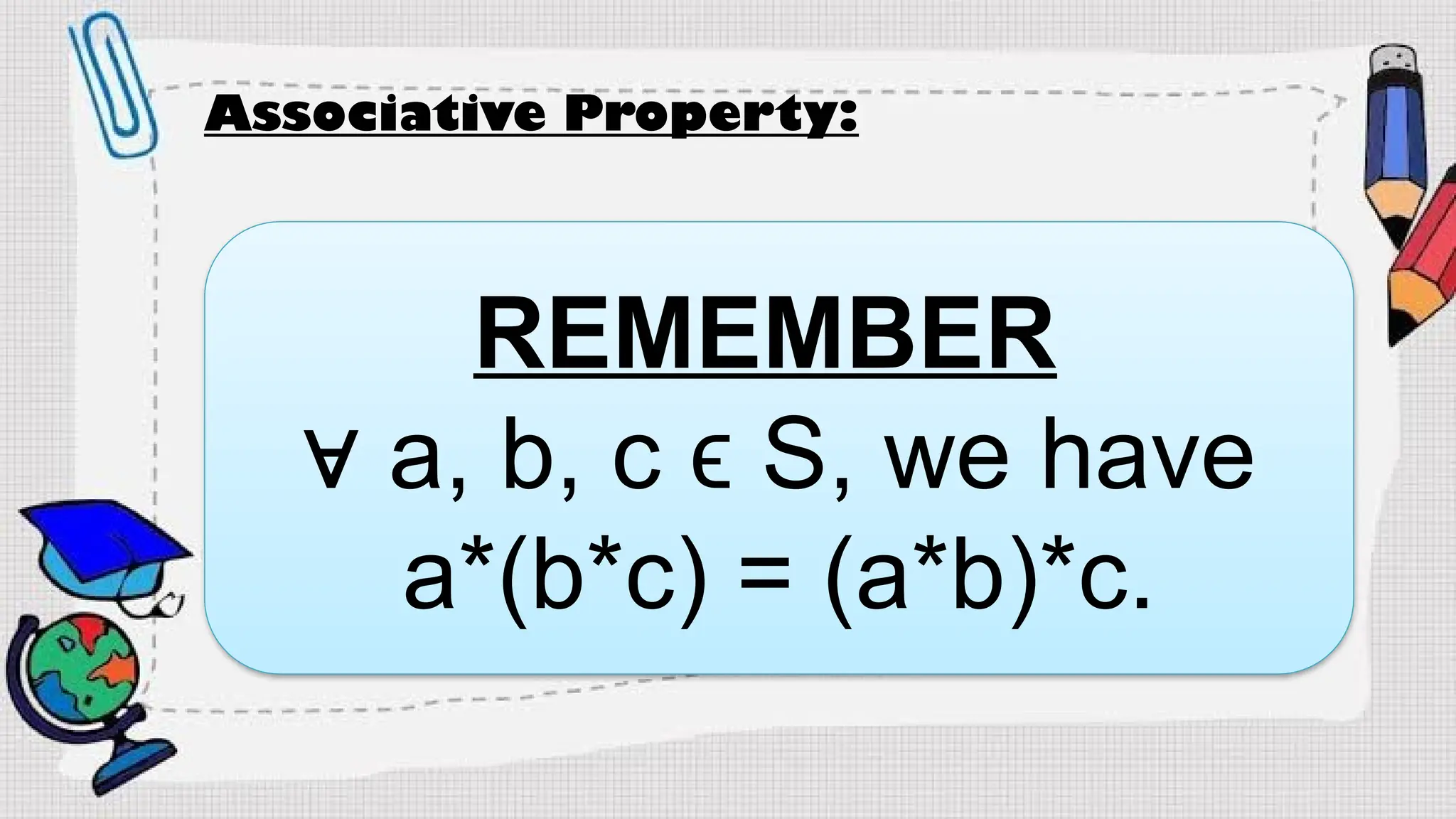

(a Ω b) Ω c = a Ω (b Ω c)

(2a) (3b) Ω c = a Ω (2b)(3c)

(6ab) Ω c = a Ω (6bc)

[2 (6ab)] (3c) = (2)(a) [3(6bc)]

(12ab) (3c) = 2a (18bc)

36abc = 36abc

⸫ a Ω b is associative.

This becomes your first

term.

This becom

es your 2nd

term

.

These things are based on the definition of

binary operations a,b ϵ S](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/groupandsubgroup-abstractal-241124180348-e73ed8cc/75/GROUP-AND-SUBGROUP-SET-ABSTRACT-ALGEBRA-TOPIC-5-22-2048.jpg)