The document discusses the concepts and mathematical principles of manifold learning and interpolation in high dimensions, focusing on the properties of topological spaces and smooth manifolds. It elaborates on techniques such as parametric curves, tangent vectors, curvature, and geodesics, providing examples and deriving key equations related to these concepts. Additionally, it includes references for further reading on differential geometry and its applications.

![Tangent space and Normal vector

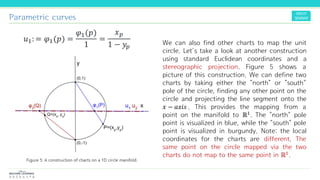

𝜎 𝑡

≝ 𝛾−1[ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜓 𝑡 + 𝑡0 + 𝛾 ∗ 𝜙 𝑡 + 𝑡1

− (𝛾 ∗ 𝜓)(𝑡0)]

p

𝑡

𝑡0 𝑡1 𝑡2

ψ 𝜙 𝜎

𝛾 ℝ 𝑛

𝑝 = ψ 𝑡0 = 𝜙(𝑡1) = 𝜎 𝑡2

𝑇ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑒𝑥𝑖𝑠𝑡 𝑎 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑣𝑒 𝜎, 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑤𝑒 𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑢𝑎𝑙𝑙𝑦

𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑟𝑢𝑐𝑡 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑤𝑖𝑙𝑙 𝑟𝑒𝑝𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑠𝑢𝑚 𝑜𝑓 𝑡𝑤𝑜 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑣𝑒𝑠

𝒱𝑝,ψ + 𝒱𝑝,𝜙 = 𝒱𝑝,𝜎

𝐼𝑡 𝑠ℎ𝑜𝑤𝑠 𝑦𝑜𝑢 ℎ𝑜𝑤 𝑤𝑒 𝑎𝑟𝑒 𝑔𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑡𝑜 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑟𝑢𝑐𝑡

𝑣𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 𝑠𝑝𝑎𝑐𝑒 ( 𝑇𝑝 𝑀) 𝑏𝑦 𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝑣𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟

𝑓 ∈ 𝐶∞

ℝ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialgeometry-200507163557/85/Differential-Geometry-for-Machine-Learning-25-320.jpg)

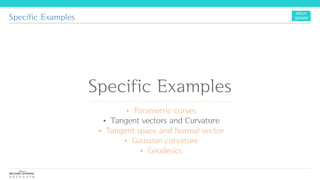

![Tangent space and Normal vector

p

𝑡

𝑡0 𝑡1 𝑡2

ψ 𝜙 𝜎

𝛾 ℝ 𝑛

𝑝 = ψ 𝑡0 = 𝜙(𝑡1) = 𝜎 𝑡2

ℝ 𝑀 ℝ

ℝ 𝑛

𝜎 𝑓

𝛾 ∗ 𝜎 𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1

𝛾

𝐿𝑒𝑡 𝑡2 = 0 𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑛,

𝜎 0 = 𝛾−1[ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜓 𝑡0 + 𝛾 ∗ 𝜙 𝑡1

−(𝛾 ∗ 𝜓)(𝑡0)]

= 𝑝

𝑓 ∈ 𝐶∞

ℝ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialgeometry-200507163557/85/Differential-Geometry-for-Machine-Learning-26-320.jpg)

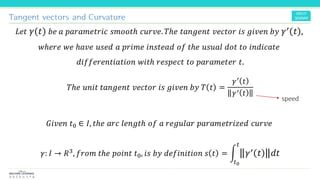

![Tangent space and Normal vector

ℝ 𝑀 ℝ

ℝ 𝑛

𝜎 𝑓

𝛾 ∗ 𝜎 𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1

𝛾

𝒱𝑝,𝜎 𝑓 = (𝑓 ∗ 𝜎)′(0) = 𝒱𝑝,ψ 𝑓 + 𝒱𝑝,𝜙 𝑓

𝒱𝑝,𝜎 𝑓 = (𝑓 ∗ 𝜎)′(0) = (𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1 ∗ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜎)′(0) = { 𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1 ∗ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜎 }′(0)

=

𝜕𝑗 𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1 𝛾 ∗ 𝜎

𝜕(𝛾 ∗ 𝜎) 𝑗

𝑑(𝛾 ∗ 𝜎) 𝑗

𝑑𝑡

[0]

𝑓](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialgeometry-200507163557/85/Differential-Geometry-for-Machine-Learning-27-320.jpg)

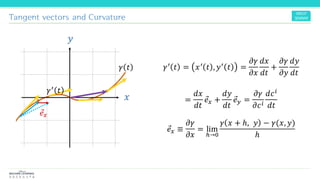

![Tangent space and Normal vector

ℝ 𝑀 ℝ

ℝ 𝑛

𝜎 𝑓

𝛾 ∗ 𝜎 𝑓 ∗ 𝛾−1

𝛾

𝑑(𝛾 ∗ 𝜎) 𝑗

𝑑𝑡

[0] = (𝛾 ∗ 𝜎) 𝑗′

0 = {𝛾 ∗ 𝛾−1 ∗ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜓 𝑡 + 𝑡0 + 𝛾 ∗ 𝛾−1 ∗ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜙 𝑡 + 𝑡0

−𝛾 ∗ 𝛾−1 ∗ 𝛾 ∗ 𝜓 𝑡0 } 𝑗′

0

= (𝛾 ∗ 𝜓) 𝑗′

𝑡0 + (𝛾 ∗ 𝜙) 𝑗′

𝑡1 = 𝒱𝑝,ψ + 𝒱𝑝,𝜙

This is not a function of 𝑡](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialgeometry-200507163557/85/Differential-Geometry-for-Machine-Learning-28-320.jpg)

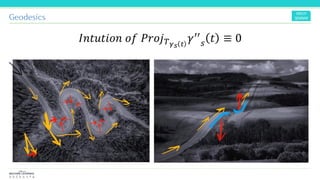

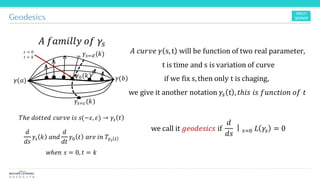

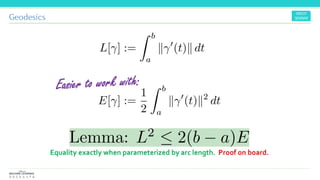

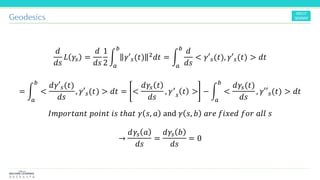

![Geodesics

න

𝑎

𝑏

<

𝑑𝛾′ 𝑠(𝑡)

𝑑𝑠

, 𝛾′ 𝑠(𝑡) > 𝑑𝑡 = <

𝑑𝛾𝑠 𝑡

𝑑𝑠

, 𝛾′

𝑠 𝑡 > − න

𝑎

𝑏

<

𝑑𝛾𝑠 𝑡

𝑑𝑠

, 𝛾′′

𝑠 𝑡 > 𝑑𝑡

= − න

𝑎

𝑏

<

𝑑𝛾𝑠 𝑡

𝑑𝑠

, 𝛾′′

𝑠 𝑡 > 𝑑𝑡 = − න

𝑎

𝑏

<

𝑑𝛾𝑠 𝑡

𝑑𝑠

, 𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑗 𝑇 𝛾 𝑠 𝑡

𝛾′′

𝑠 𝑡 > 𝑑𝑡 = 0

𝑇ℎ𝑖𝑠 𝑖𝑚𝑙𝑖𝑒𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑎𝑡 𝑖𝑓 𝑎 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑣𝑒 𝛾: 𝑎, 𝑏 → 𝑀 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑔𝑒𝑜𝑑𝑒𝑠𝑖𝑐, 𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑛

𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑗 𝑇 𝛾 𝑠 𝑡

𝛾′′

𝑠 𝑡 = 0

𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑡 ∈ [𝑎, 𝑏]

= 0

Note that it is in 𝑇𝛾𝑠 𝑡](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/differentialgeometry-200507163557/85/Differential-Geometry-for-Machine-Learning-41-320.jpg)