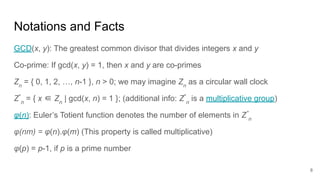

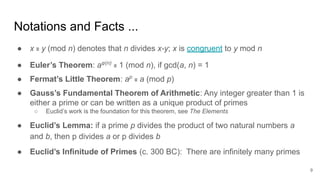

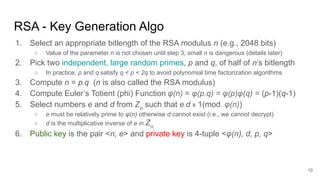

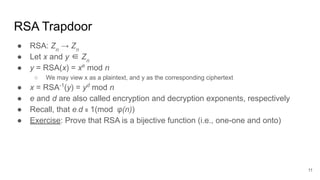

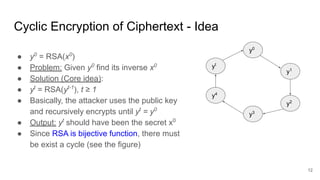

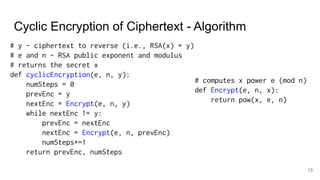

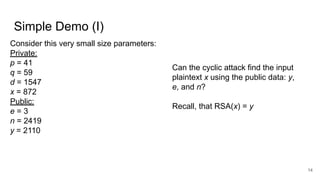

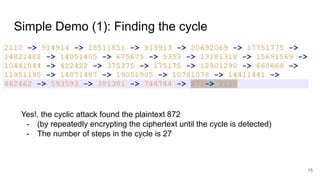

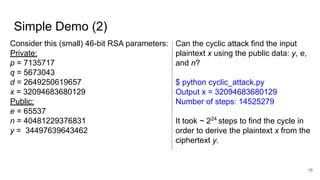

The document explores the implications of repeatedly encrypting a ciphertext using RSA, discussing whether a secret can be uncovered through cyclic encryption. It explains the RSA key generation process, the underlying mathematical concepts, and demonstrates how an attacker can find the plaintext through a cyclic attack, although this method is noted to have exponential complexity and is not a practical threat. The conclusion emphasizes the importance of using proper padding techniques in RSA encryption to mitigate vulnerabilities.