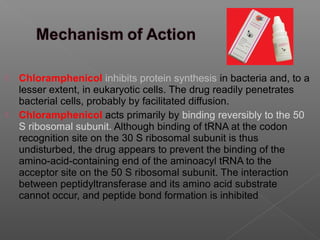

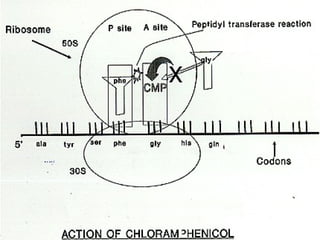

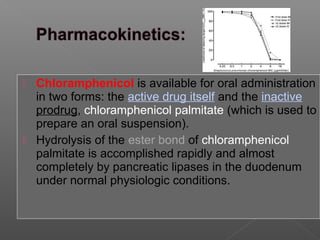

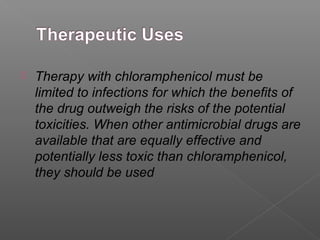

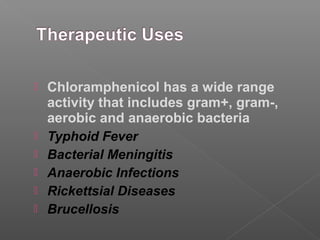

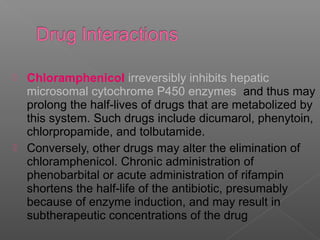

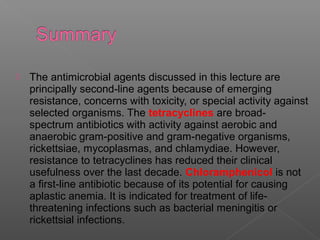

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic produced by Streptomyces venezuelae. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit, preventing binding of aminoacyl tRNA and inhibiting peptide bond formation. It can also inhibit mitochondrial protein synthesis. Chloramphenicol is administered orally or intravenously and is well absorbed. It is indicated for serious infections such as meningitis or typhoid fever. However, it carries risks of bone marrow suppression and aplastic anemia.