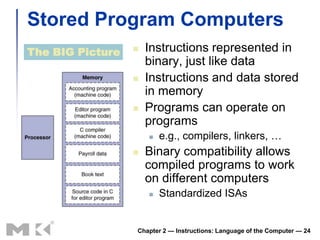

This document discusses how computers represent and manipulate data at the lowest levels. It covers:

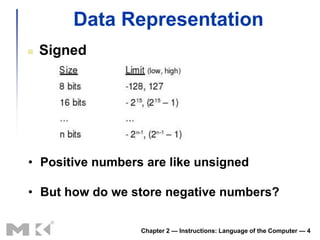

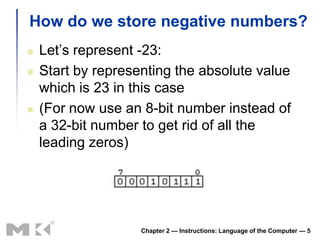

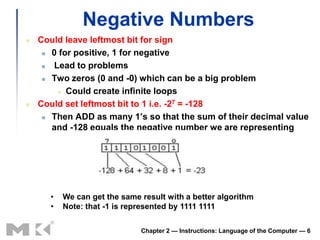

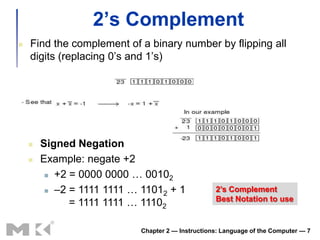

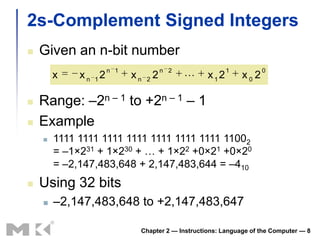

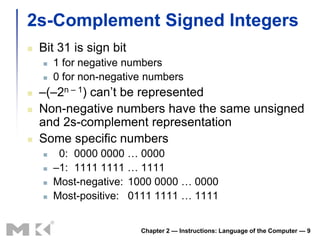

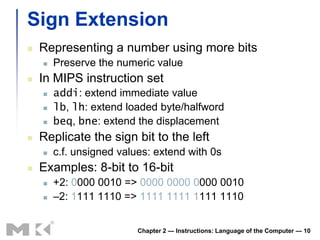

1) How integers are represented in binary and how signed and unsigned integers work with 2's complement representation.

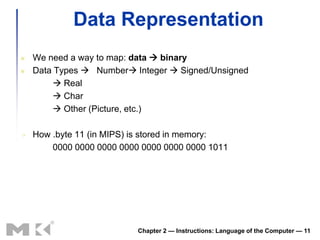

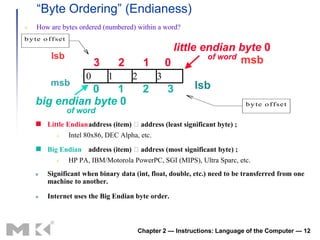

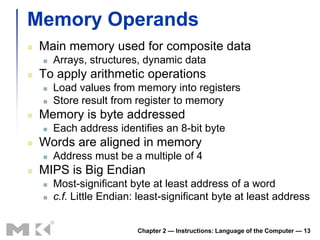

2) Data types like integers, real numbers, characters that are mapped to binary representations. Issues like byte ordering and memory addressing are also covered.

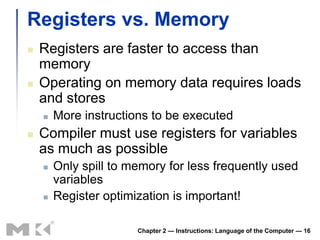

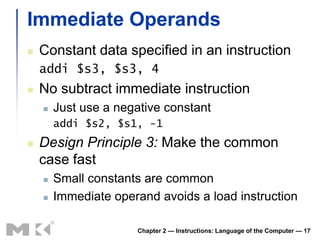

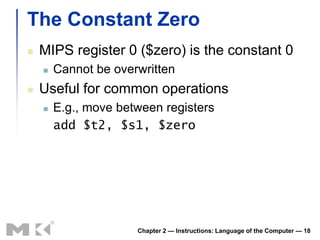

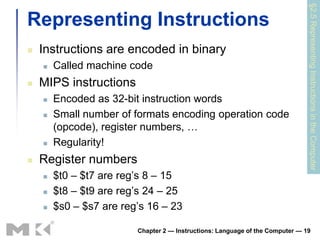

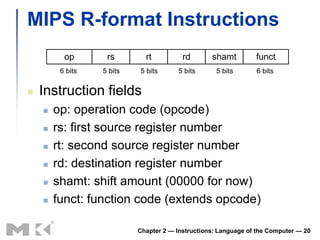

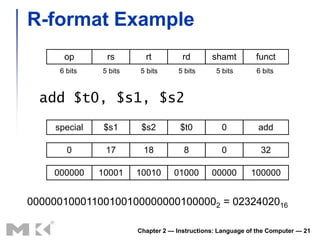

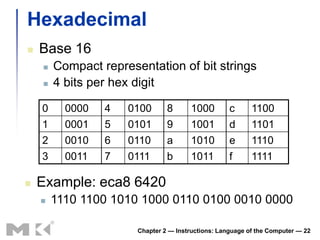

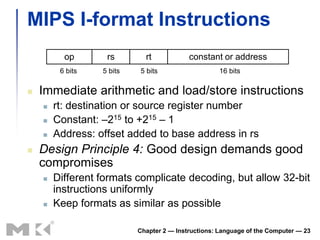

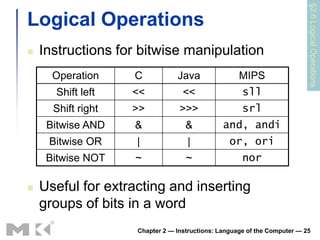

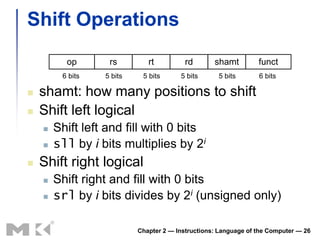

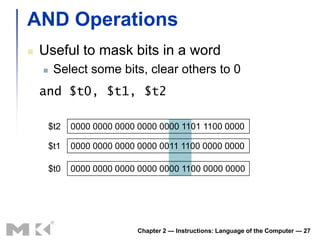

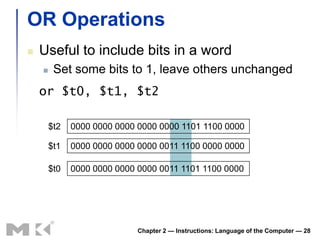

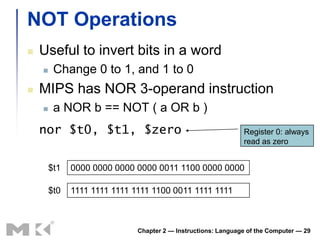

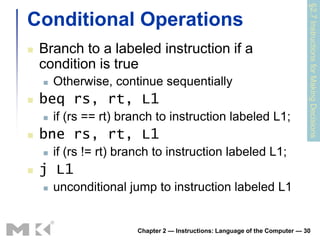

3) How instructions are encoded in binary machine code and the different instruction formats used in MIPS, including the R-format and I-format. Logical operations like shifting, AND, and OR that manipulate bits are also introduced.

![Data Representation

Integers

A decimal example

2734 = 2 * 103 + 7 * 102 + 3 * 101 + 4 * 100

A binary example

[01011]2 = 0 * 24 + 1 * 23 + 0 * 22 + 1 * 21 + 1 * 20 = [11] 10

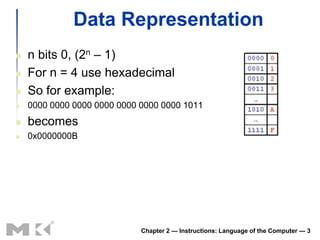

Unsigned

Unsigned integers are positive

(or to be more precise, do not have a sign)

Using 32 bits

0 to +4,294,967,295

Chapter 2 — Instructions: Language of the Computer — 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2-part2-a-100223113253-phpapp02/85/Chapter-2-Part2-A-2-320.jpg)

![Memory Operand Example 1

C code:

g = h + A[8];

g in $s1, h in $s2, base address of A in $s3

Compiled MIPS code:

Index 8 requires offset of 32

4 bytes per word

lw $t0, 32($s3) # load word

add $s1, $s2, $t0

offset base register

Chapter 2 — Instructions: Language of the Computer — 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2-part2-a-100223113253-phpapp02/85/Chapter-2-Part2-A-14-320.jpg)

![Memory Operand Example 2

C code:

A[12] = h + A[8];

h in $s2, base address of A in $s3

Compiled MIPS code:

Index 8 requires offset of 32

lw $t0, 32($s3) # load word

add $t0, $s2, $t0

sw $t0, 48($s3) # store word

Chapter 2 — Instructions: Language of the Computer — 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2-part2-a-100223113253-phpapp02/85/Chapter-2-Part2-A-15-320.jpg)