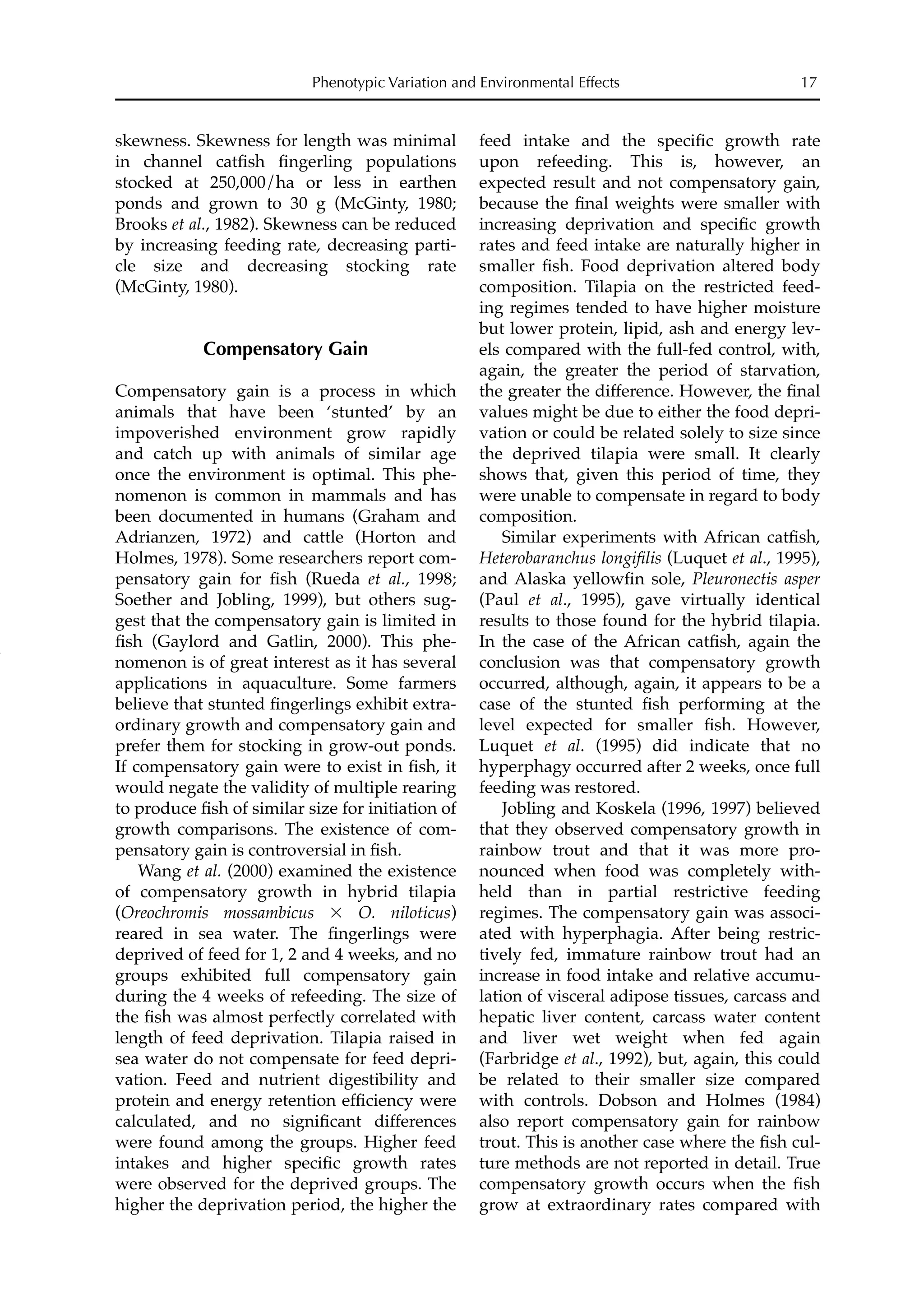

This chapter provides a brief history of aquaculture and fisheries, noting that while aquaculture is an ancient practice, it has grown tremendously in recent decades. Genetic biotechnology has also made significant advances in improving farmed species since the 1980s. However, commercial fisheries still have higher economic value than aquaculture globally. Natural fish populations are important gene banks that can provide genetic variation for aquaculture breeding programs. Recreational fishing also has high economic value. Biotechnology impacts both aquaculture and fisheries due to their interrelationships, and will be important for managing wild stocks and conserving genetic diversity. Meeting future global demand for seafood will require expanding aquaculture production through genetic improvement techniques

![the International Council for the Exploration

of the Sea (ICES) and the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) in the USA. Common

denominators of the legislation or guidelines

are licensing for field trials and release of

GMOs, notification that a GMO is being

exported/imported and released and an

environmental impact assessment. Members

of the EU agreed to uniform licensing pro-

cedures for testing and sales of GMOs,

directing that, if a GMO was licensed in one

country, field testing, release and sale should

also be allowed in the other countries.

However, European countries have not

adhered to this policy, some operating

strictly under home rule and others over-

turning approvals granted earlier by previ-

ous administrations. Politics and

protectionism appear to have major roles in

the decision-making process.

EC Directive 94/15/EC/ of 15 April 1994

(Council Directive 90/220/EEC) requires

notification that a GMO is to be deliberately

released in the environment (Bartley, 1999;

Dunham et al., 2001; FAO, 2001). The direc-

tive includes requirements for impact assess-

ment, control and risk assessment.

Requirements are different for higher plants

and other organisms, and the definition of

release includes placement on the market.

In 1992, the CBD (UNCED, 1994), which

includes 175 countries, requested the estab-

lishment of ‘means to regulate, manage or

control the risks associated with the use and

release of LMOs [living modified organisms]

… which are likely to have adverse environ-

mental impacts’ (Article 8g). CBD also

requests legislative, policy or administrative

measures to support biotechnological

research, especially in those countries that

provide genetic resources (Article 19).

Additionally, Article 19 (3) directs participat-

ing countries to consider the establishment

of internationally binding protocols for the

safe transfer, handling and utilization of

LMOs that have a potentially adverse effect

on the conservation and sustainable use of

biological diversity.

The Convention seeks to promote

biosafety regimes to allow the conservation

of biodiversity as well as the sustainable use

of biotechnology (Bartley, 1999; Dunham et

al., 2001; FAO, 2001). Article 14 mandates

each signatory to require environmental

impact assessments of proposed projects that

are likely to have adverse effects on biologi-

cal diversity, with the goal of avoiding or

minimizing such effects. A Working Group

on Biosafety developed a biosafety protocol,

and each country was encouraged to

develop central units capable of collecting

and analysing data and to require industry

to share their technical knowledge with gov-

ernments. A worldwide data bank was sug-

gested that would collect information on

GMOs and manage research on their envi-

ronmental effects. Some, but not all, of the

participating countries agreed that industry

has a responsibility to inform governments

of countries when it wishes to produce or

export genetically modified (GM) foods.

The sixth meeting of the Working Group

on Biosafety was held in February 1999 to

finalize the International Protocol on

Biosafety on transport between countries of

living GMOs. The meeting was not success-

ful, with a few nations blocking final

approval (Pratt, 1999). Delegates were

divided along issues such as: whether or not

to have the precautionary principle drive

biosafety decisions; liability in the case of

negative effects on human health or biodi-

versity; possible social and economic

impacts on rural cultures; whether or not to

regulate movement across borders of prod-

ucts derived from genetically engineered

crops; and whether to segregate and label

genetically engineered crops and, possibly,

their derived products. The negotiations,

development and ratification of these proto-

cols are ongoing (www.biodiv.org).

Article 9.3 of the FAO CCRF addresses the

‘Use of aquatic genetic resources for the pur-

poses of aquaculture including culture-based

fisheries’ (Bartley, 1999; Kapuscinski et al.,

1999; Dunham et al., 2001; FAO, 2001). The

key components of this article recommend the

conservation of genetic diversity and ecosys-

tem integrity, minimization of the risks from

non-native species and genetically altered

stocks, creation and implementation of rele-

vant codes of practice and procedures and

adoption of appropriate practices in the

genetic improvement and selection of brood

236 Chapter 16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aquacultureandfisheriesbiotechnologygeneticapproaches-150131142625-conversion-gate02/75/Aquaculture-and-fisheries-biotechnology-genetic-approaches-249-2048.jpg)