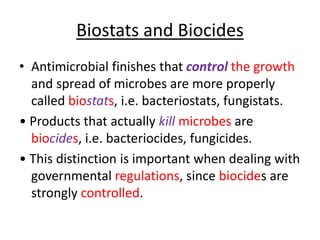

This document discusses various types of antimicrobial finishes for textiles. It describes two aspects of antimicrobial protection: preventing pathogenic microbes and protecting the textile itself. Problems caused by microbial growth include functional, hygienic and aesthetic issues. The document then covers the mechanisms of antimicrobial finishes including controlled release and bound mechanisms. It provides examples of specific antimicrobial chemicals and finishes like triclosan, quaternary ammonium salts, organosilver, and chitosan. Fields of application include industrial, home, and medical textiles.