This document provides an overview of the 7th edition of the textbook "Accounting Information Systems" by James A. Hall. It includes brief contents, preface information, and acknowledgments. The textbook is published by Cengage Learning and covers topics such as transaction processing, systems development, database management, and computer controls and auditing within accounting information systems.

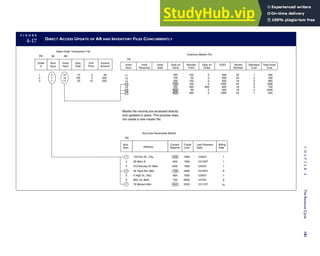

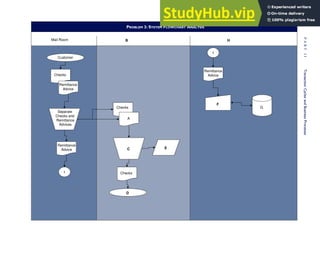

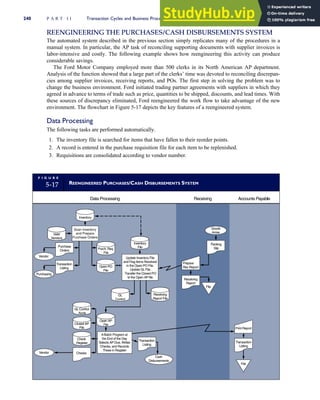

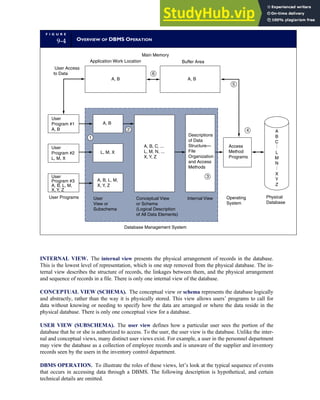

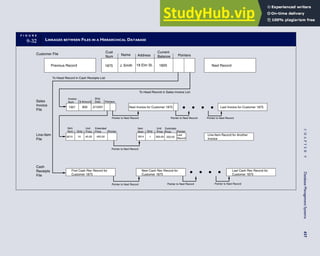

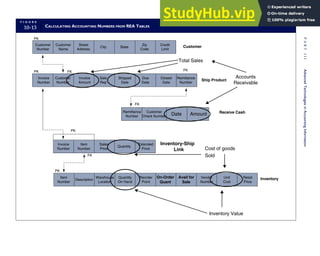

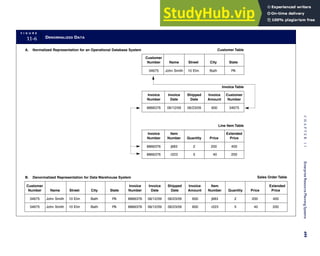

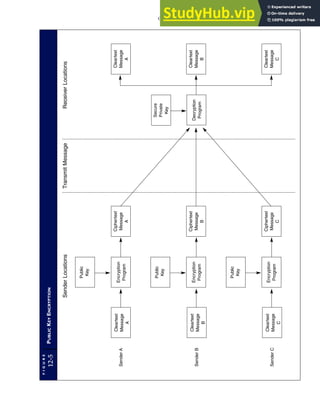

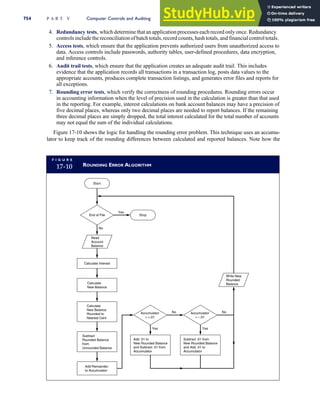

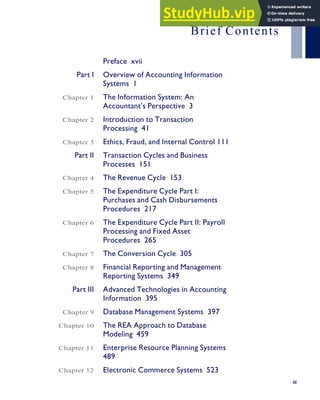

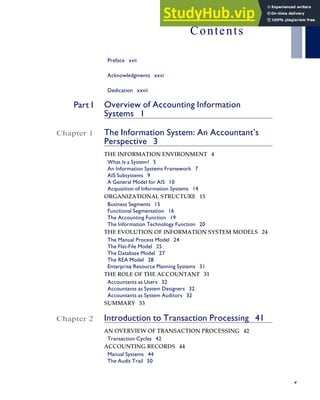

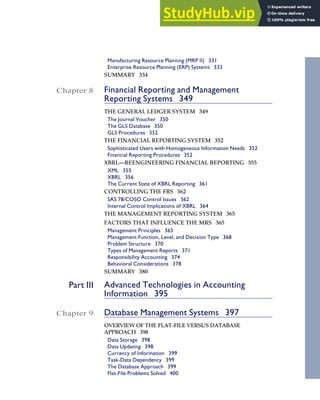

![separate aspect of the transaction. Data pertaining to the customer, the invoice, specific items sold, and so

on can thus be captured for multiple uses and users. The tables of the database are linked via common

attributes called primary keys (PK) and embedded foreign keys (FK) that permit integration. In contrast,

the files in the traditional system are independent of each other and thus cannot accommodate such

detailed data gathering. As a result, traditional systems must summarize event data at the loss of poten-

tially important facts.

Traditional accounting records including journals, ledgers, and charts of accounts do not exist as phys-

ical files or tables under the REA model. For financial reporting purposes, views or images of traditional

accounting records are constructed from the event tables. For example, the amount of Smith’s account re-

ceivable balance is derived from [total sales (Quant sold * Sale price) less cash received (Amount) ¼ 350

200 ¼ 150]. If necessary or desired, journal entries and general ledger amounts can also be derived from

these event tables. For example, the Cost-of-Goods-Sold control account balance is (Quant sold * Unit

cost) summed for all transactions for the period.

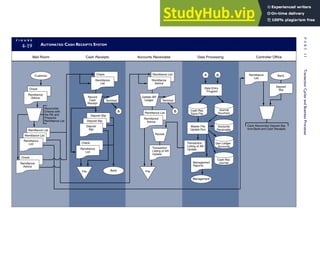

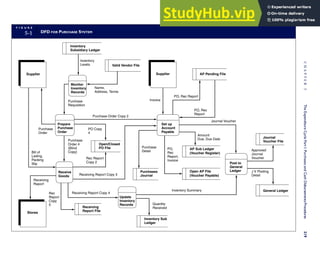

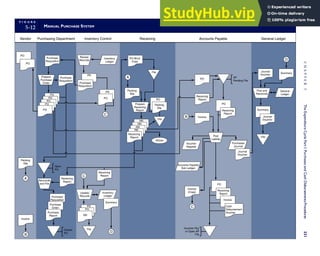

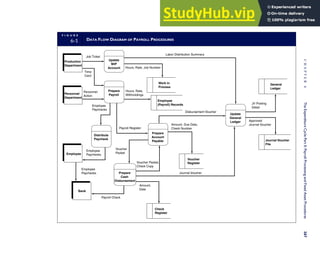

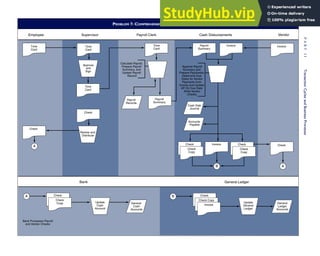

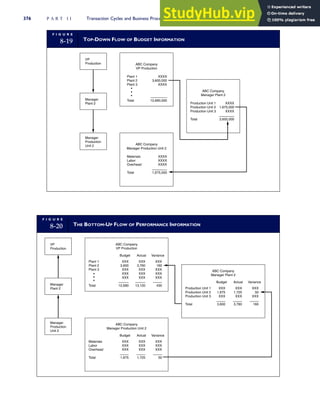

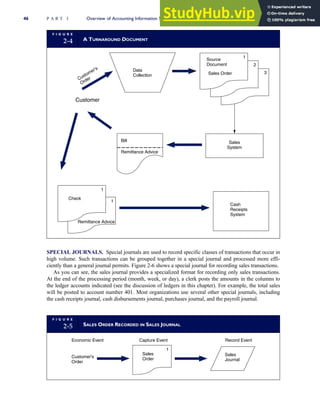

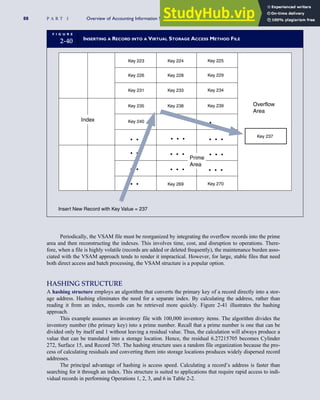

F I G U R E

1-15 EVENT DATABASE IN AN REA SYSTEM

CUSTOMER Table

INVOICE Table

LINE ITEM Table

PRODUCT Table

CASH REC Table

Amount

Sale

Price

Unit

Cost QOH

Description

Product

Num

Trans

Num

Product

Num

Invoice

Num

Invoice

Num

Invoice

Date

Ship

Date Terms Carrier

Cust

Num

Quant

Sold

5

10

Cust

Num

Check

Num

Check

Date

Date

Posted

(PK)

(PK) (FK)

(PK)

(PK)

(PK)

(FK)

(FK)

Something or other

98765

98765

X21

Something else

Y33

X21

98765 9/01/09 9/03/09 Net 30 UPS 23456

23456 Smith 125 Elm St., City 610-555-1234 $5,000 12 12/9/89

Y33

Reorder

Point

50

60

200

159

9/30/09

9/28/09

451

23456

77654

$22

$16

$30

$20

$200

Cust

Num Name Address Tel Num

Credit

Limit

Billing

Date Anniver

30 P A R T I Overview of Accounting Information Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountinginformationsystemsseventhedition-230807175400-3dbae3ad/85/Accounting-Information-Systems-SEVENTH-EDITION-pdf-59-320.jpg)

![analysis of the nature and social impact of computer technology and the corresponding formulation and jus-

tification of policies for the ethical use of such technology.… [This includes] concerns about software as

well as hardware and concerns about networks connecting computers as well as computers themselves.’’3

One researcher has defined three levels of computer ethics: pop, para, and theoretical.4

Pop computer

ethics is simply the exposure to stories and reports found in the popular media regarding the good or bad ram-

ifications of computer technology. Society at large needs to be aware of such things as computer viruses and

computer systems designed to aid handicapped persons. Para computer ethics involves taking a real interest

in computer ethics cases and acquiring some level of skill and knowledge in the field. All systems professio-

nals need to reach this level of competency so they can do their jobs effectively. Students of accounting infor-

mation systems should also achieve this level of ethical understanding. The third level, theoretical computer

ethics, is of interest to multidisciplinary researchers who apply the theories of philosophy, sociology, and psy-

chology to computer science with the goal of bringing some new understanding to the field.

A New Problem or Just a New Twist on an Old Problem?

Some argue that all pertinent ethical issues have already been examined in some other domain. For exam-

ple, the issue of property rights has been explored and has resulted in copyright, trade secret, and patent

laws. Although computer programs are a new type of asset, many believe that these programs should be

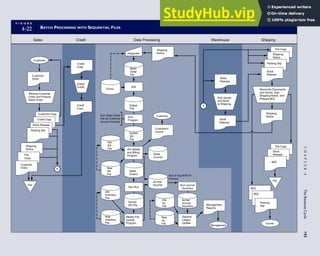

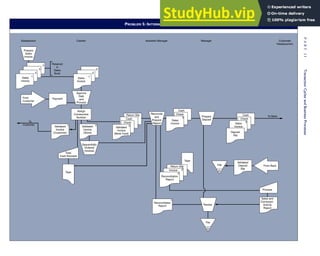

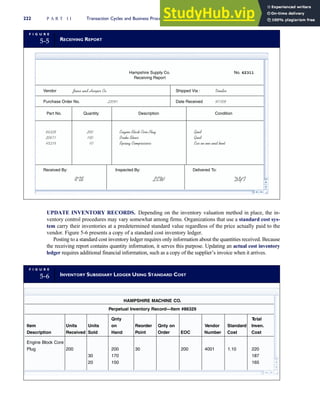

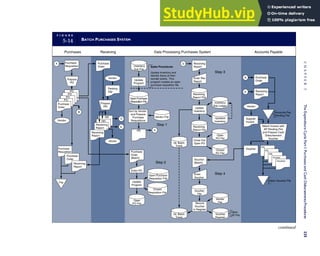

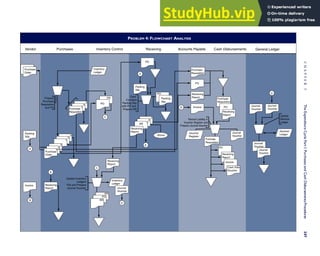

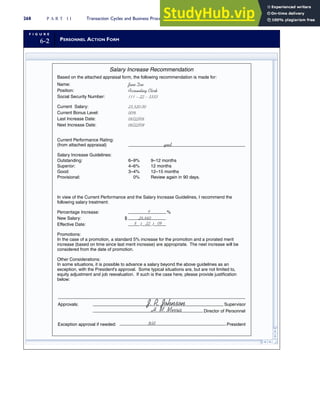

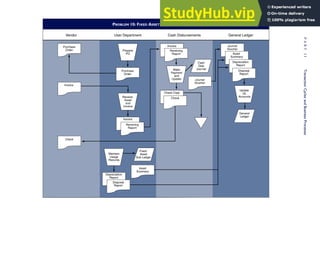

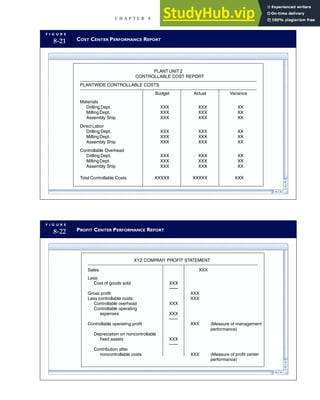

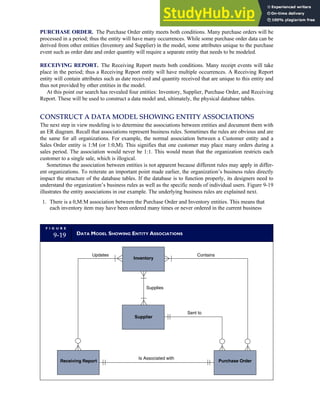

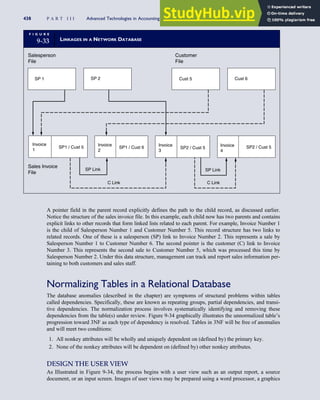

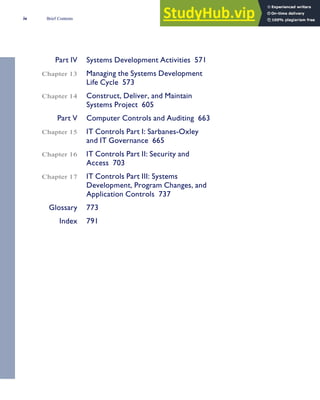

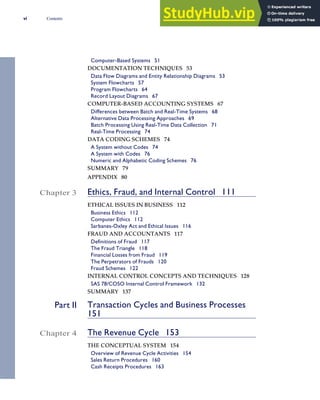

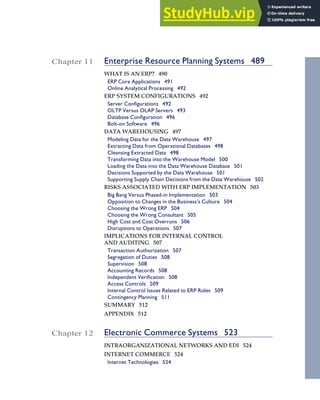

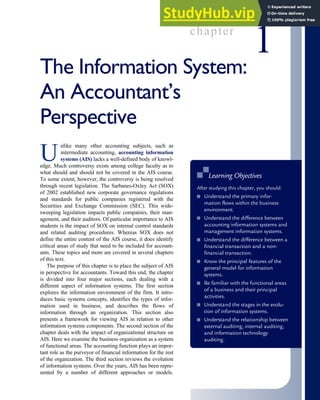

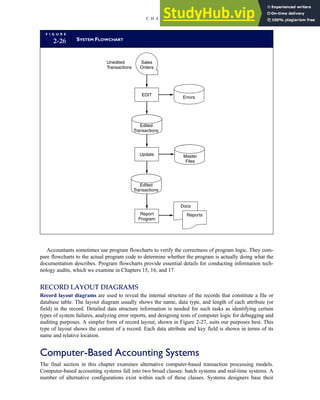

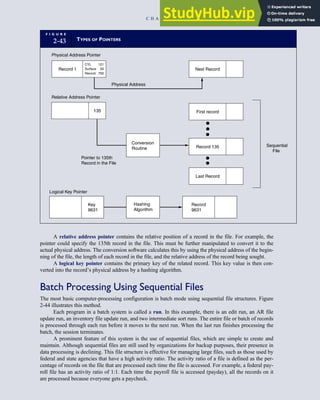

T A B L E

3-1 ETHICAL ISSUES IN BUSINESS

Equity Executive Salaries

Comparable Worth

Product Pricing

Rights Corporate Due Process

Employee Health Screening

Employee Privacy

Sexual Harassment

Diversity

Equal Employment Opportunity

Whistle-Blowing

Honesty Employee and Management Conflicts of Interest

Security of Organization Data and Records

Misleading Advertising

Questionable Business Practices in Foreign Countries

Accurate Reporting of Shareholder Interests

Exercise of Corporate Power Political Action Committees

Workplace Safety

Product Safety

Environmental Issues

Divestment of Interests

Corporate Political Contributions

Downsizing and Plant Closures

Source: The Conference Board, ‘‘Defining Corporate Ethics,’’ in P. Madsen and J. Shafritz, Essentials of Business Ethics (New York:

Meridian, 1990): 18.

3 J. H. Moor, ‘‘What Is Computer Ethics?’’ Metaphilosophy 16 (1985): 266–75.

4 T. W. Bynum, ‘‘Human Values and the Computer Science Curriculum’’ (Working paper for the National Conference on

Computing and Values, August 1991).

C H A P T E R 3 Ethics, Fraud, and Internal Control 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountinginformationsystemsseventhedition-230807175400-3dbae3ad/85/Accounting-Information-Systems-SEVENTH-EDITION-pdf-142-320.jpg)

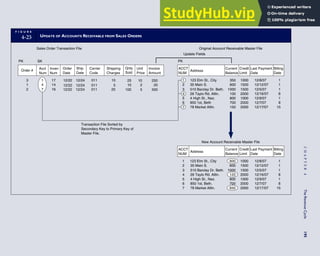

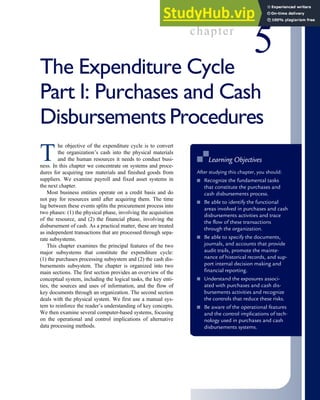

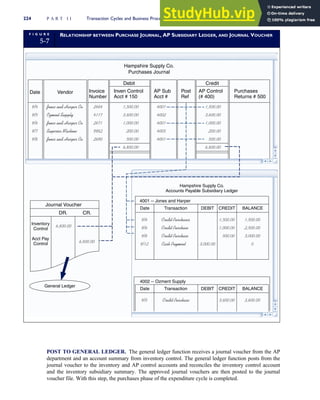

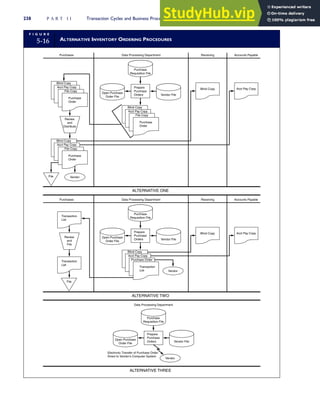

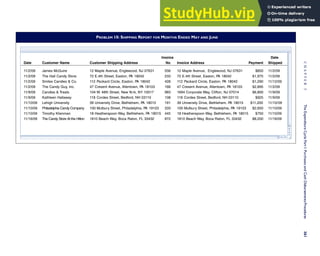

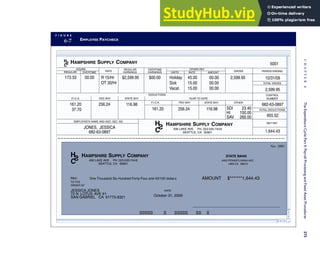

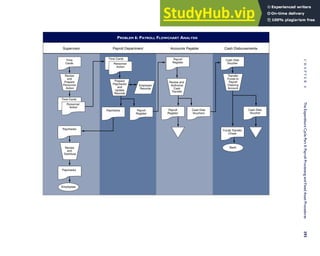

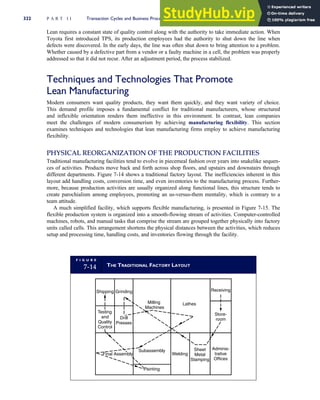

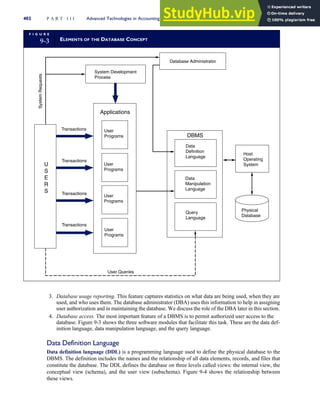

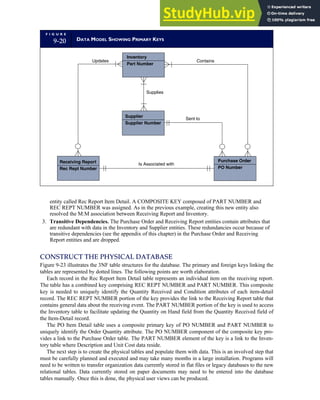

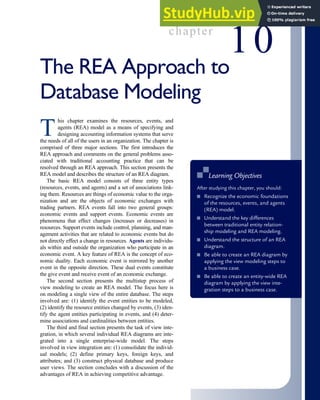

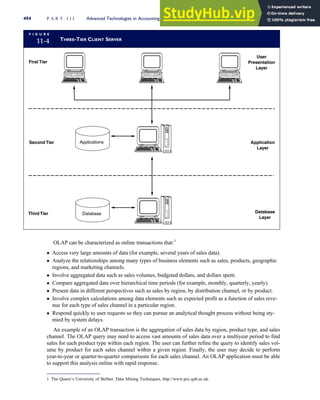

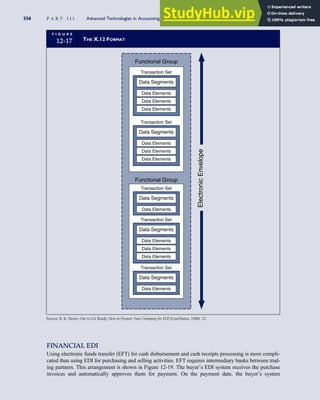

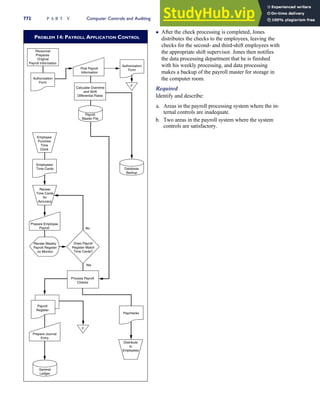

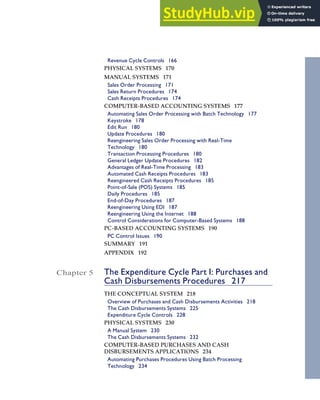

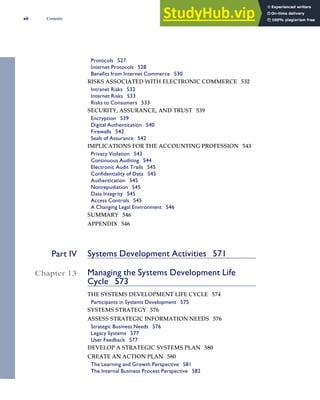

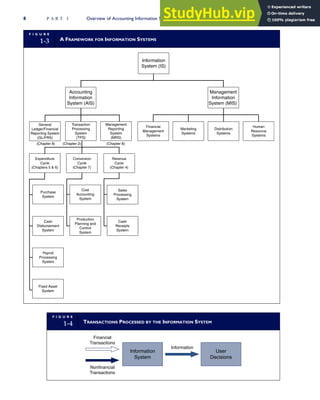

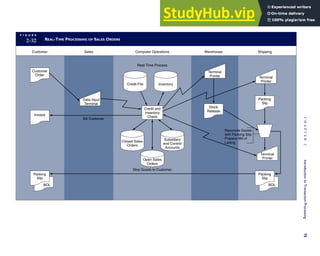

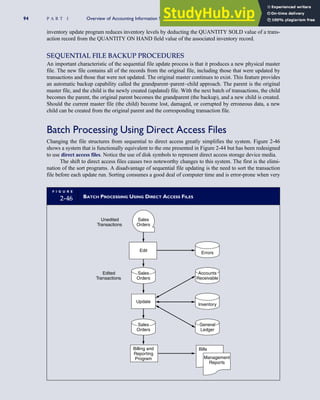

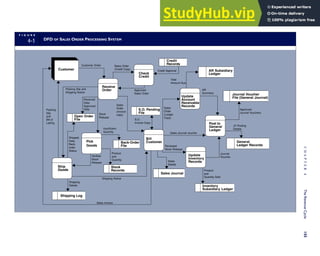

![F I G U R E

4-3 BILL OF LADING

Signature below signifies that the goods

described above are in apparent good

order, except as noted. Shipper hereby

certifies that he is familiar with all the bill

of lading terms and agrees with them.

IF WITHOUT RECOURSE:

The carrier shall not make delivery of

this shipment without payment of freight

(Signature of Consignor)

The agreed or declared value of the

property is hereby specifically stated by

the shipper to be not exceeding:

$ per

FREIGHT CHARGES

Check appropriate box:

[ ] Freight prepaid

[ ] Collect

[ ] Bill to shipper

CARRIER

Monterey Peninsula Co-op

PER DATE

SHIPPER

PER

TOTAL CHARGES $

No.

Shipping

Units

Kind of packaging,

description of articles,

special marks and exceptions Weight Rate Charges

(Name of Carrier)

TO:

Consignee

Street

City/State

Zip Code

Monterey Peninsula Co-Op

527 River Road

Chicago, IL 60612

(312) 555-0407

(This bill of lading is to be signed

by the shipper and agent of the

carrier issuing same.)

CONSIGNEE

Route: Vehicle

Shipper No.

Carrier No.

Date

Document No.

158 P A R T I I Transaction Cycles and Business Processes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountinginformationsystemsseventhedition-230807175400-3dbae3ad/85/Accounting-Information-Systems-SEVENTH-EDITION-pdf-187-320.jpg)