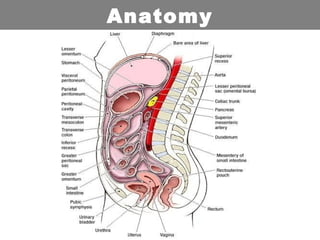

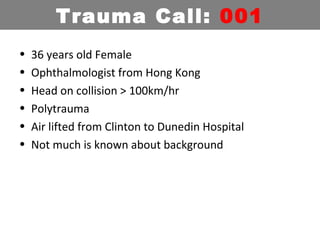

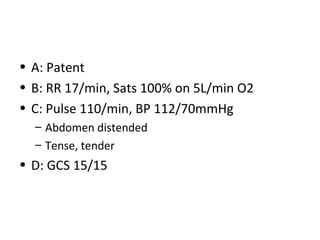

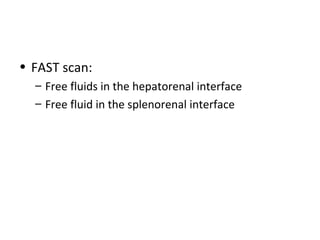

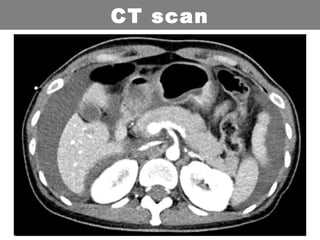

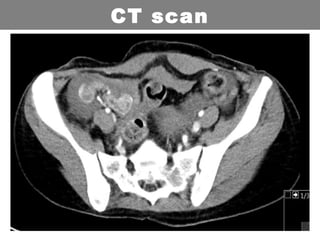

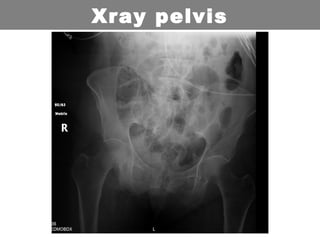

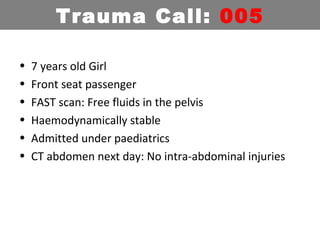

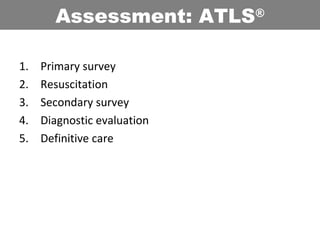

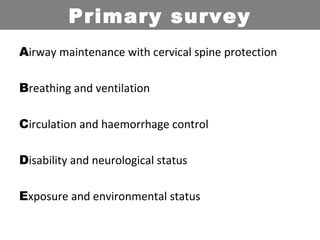

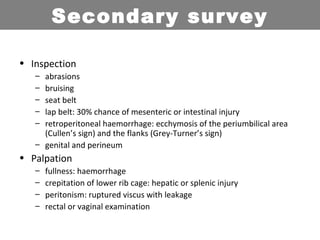

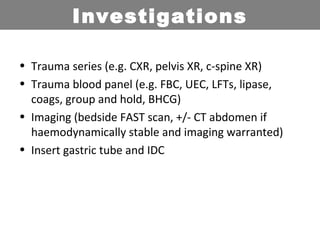

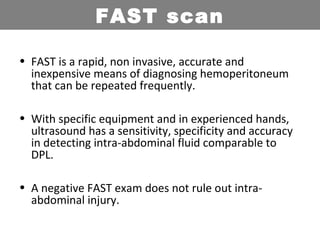

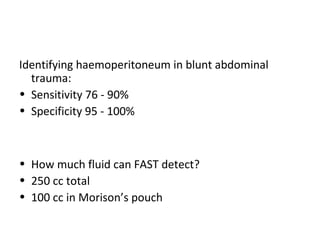

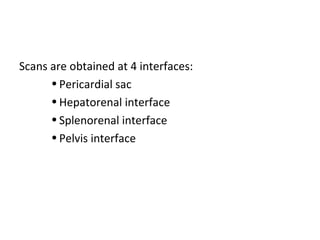

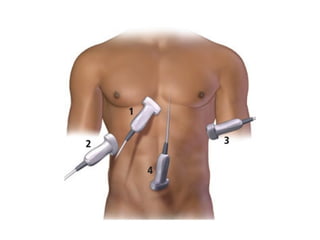

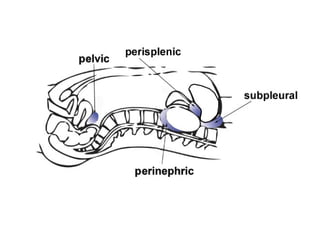

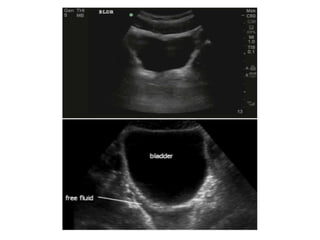

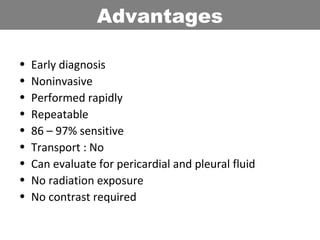

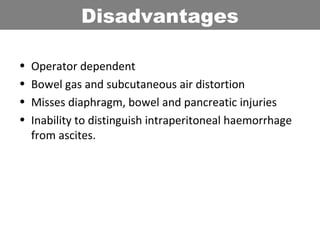

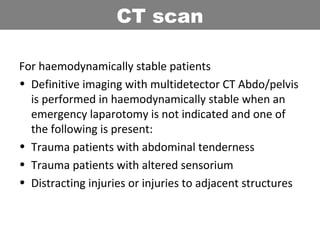

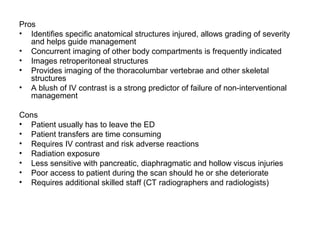

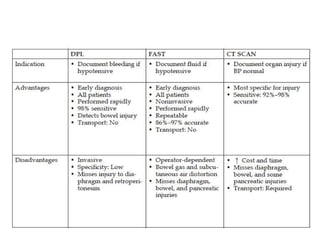

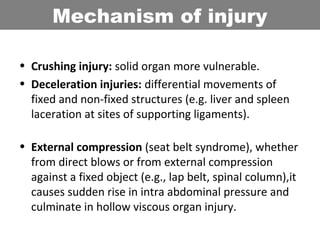

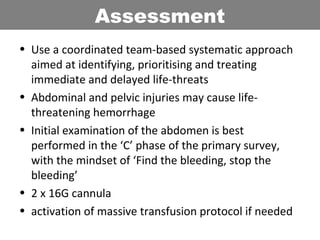

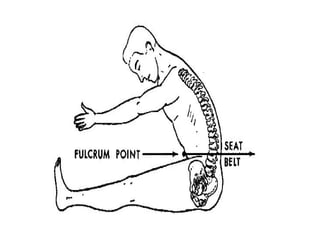

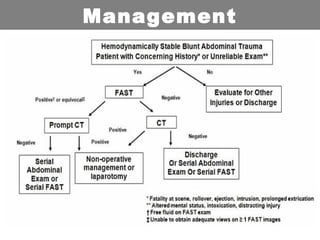

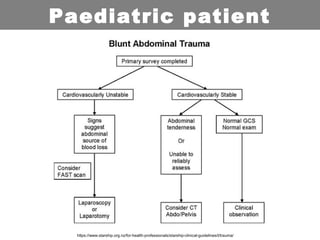

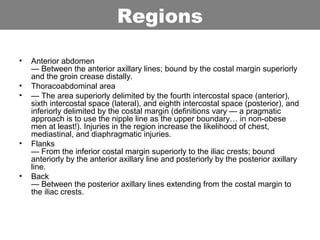

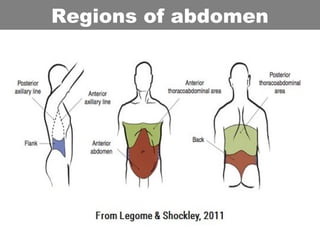

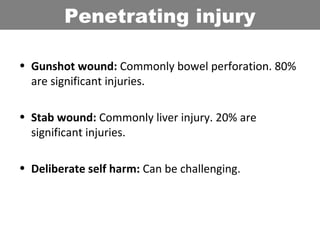

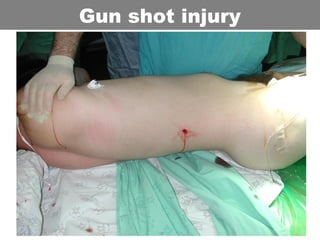

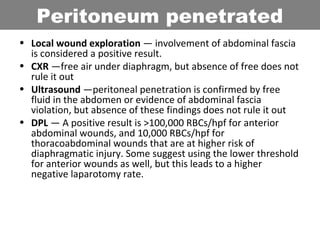

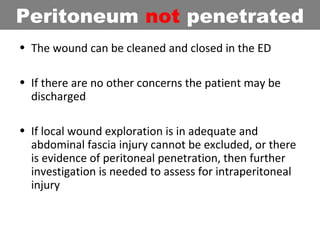

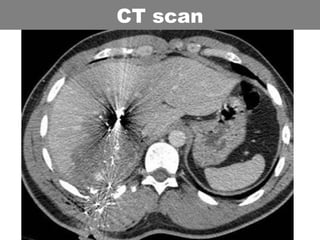

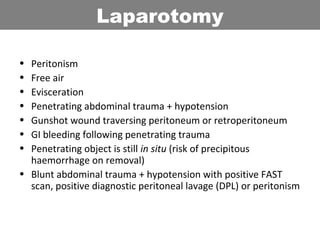

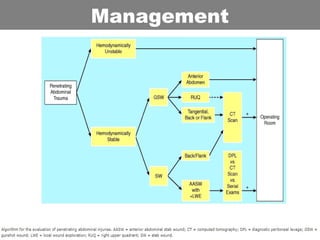

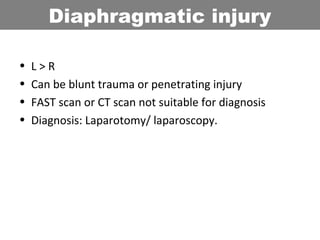

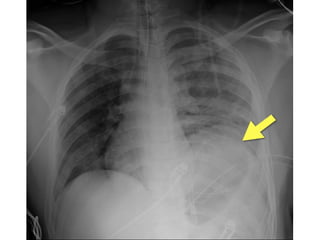

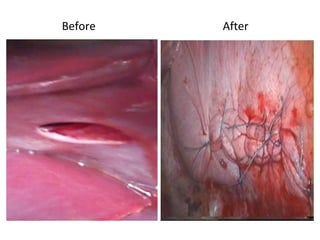

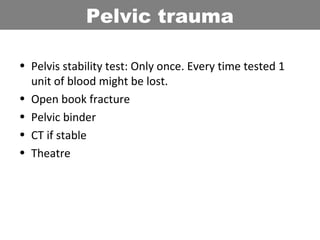

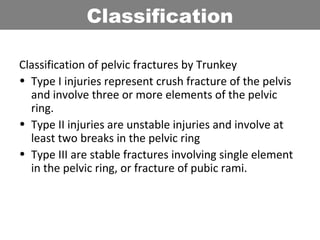

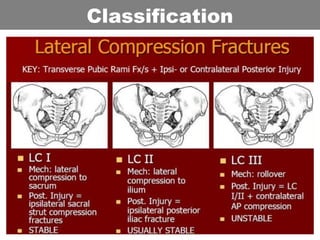

This document provides an overview of abdominal trauma, including blunt and penetrating injuries. It discusses the anatomy, mechanisms of injury, assessment techniques like the FAST scan and CT scan, management principles, and specific injuries to the liver, spleen, diaphragm, and pelvis. Treatment may involve resuscitation, laparotomy, interventional radiology, or observation depending on the stability of the patient and findings on imaging and examination. Unrecognized abdominal injuries can be preventable causes of death, so early recognition and management of intra-abdominal injuries is important for saving lives.