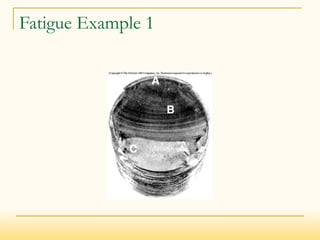

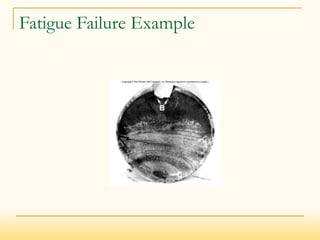

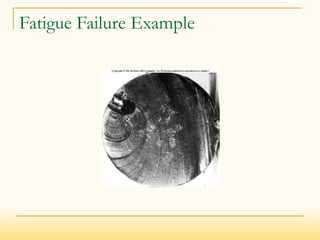

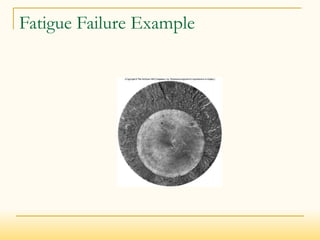

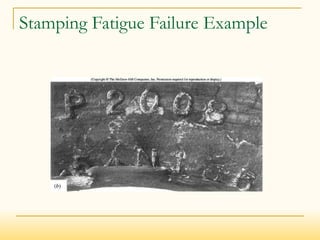

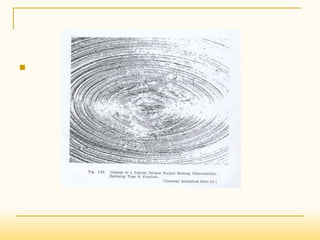

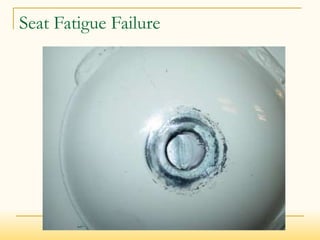

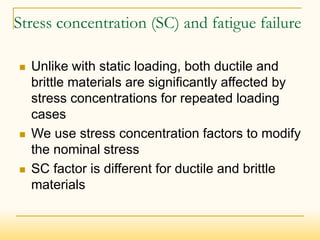

The document discusses fatigue failure and fatigue analysis. It begins by explaining that fatigue failure starts with a crack, usually at a stress concentration, which then propagates until sudden fracture. It then provides examples of fatigue failures and discusses different fatigue analysis methods. The key points are:

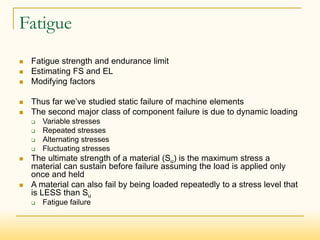

- Fatigue failure results from repeated or fluctuating stresses that are lower than the material's ultimate strength.

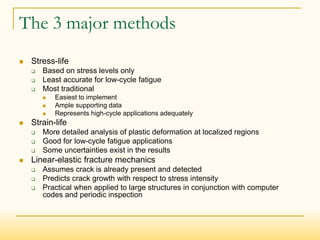

- It can be analyzed using stress-life, strain-life, or fracture mechanics methods, with stress-life most common for high-cycle fatigue.

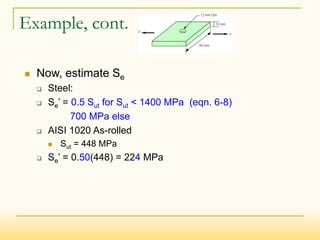

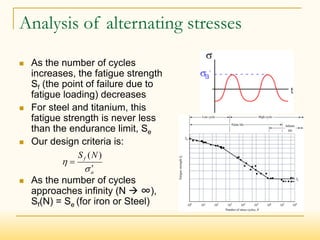

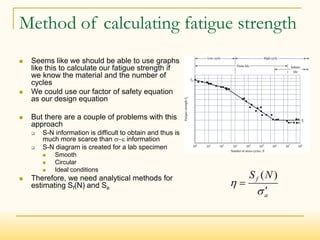

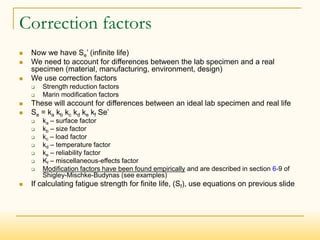

- The stress-life approach estimates fatigue strength (Sf) based on stress levels and uses modifying factors to account for real-world differences from test specimens.

![Endurance limit modifying factors

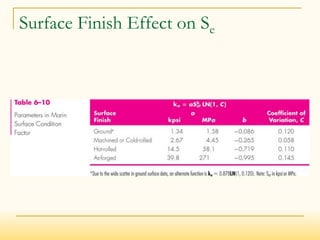

Surface (ka)

Accounts for different surface finishes

Ground, machined, cold-drawn, hot-rolled, as-forged

Size (kb)

Different factors depending on loading

Bending and torsion (see pg. 280)

Axial (kb = 1)

Loading (kc)

Endurance limits differ with Sut based on fatigue loading (bending, axial, torsion)

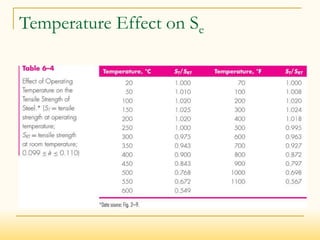

Temperature (kd)

Accounts for effects of operating temperature (Not significant factor for T<250 C [482 F])

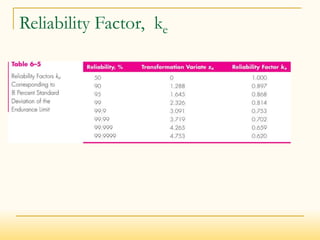

Reliability (ke)

Accounts for scatter of data from actual test results (note ke=1 gives only a 50% reliability)

Miscellaneous-effects (kf)

Accounts for reduction in endurance limit due to all other effects

Reminder that these must be accounted for

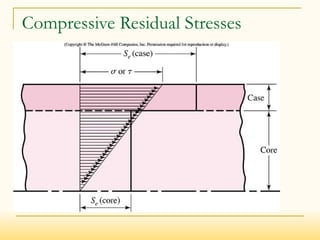

Residual stresses

Corrosion

etc](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fatiqueload-210131073535/85/7-Machine-design-fatigue-load-22-320.jpg)

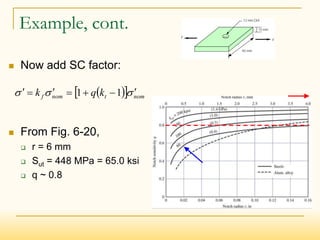

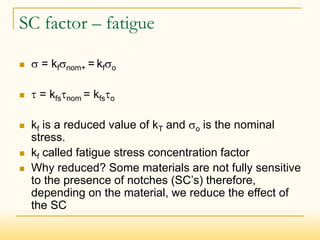

![Fatigue SC factor

kf = [1 + q(kt – 1)]

kfs = [1 + qshear(kts – 1)]

kt or kts and nominal stresses

Table A-15 & 16 (pages 1006-1013 in Appendix)

q and qshear

Notch sensitivity factor

Find using figures 6-20 and 6-21 in book (Shigley) for steels

and aluminums

Use q = 0.20 for cast iron

Brittle materials have low sensitivity to notches

As kf approaches kt, q increasing (sensitivity to notches, SC’s)

If kf ~ 1, insensitive (q = 0)

Property of the material](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fatiqueload-210131073535/85/7-Machine-design-fatigue-load-30-320.jpg)