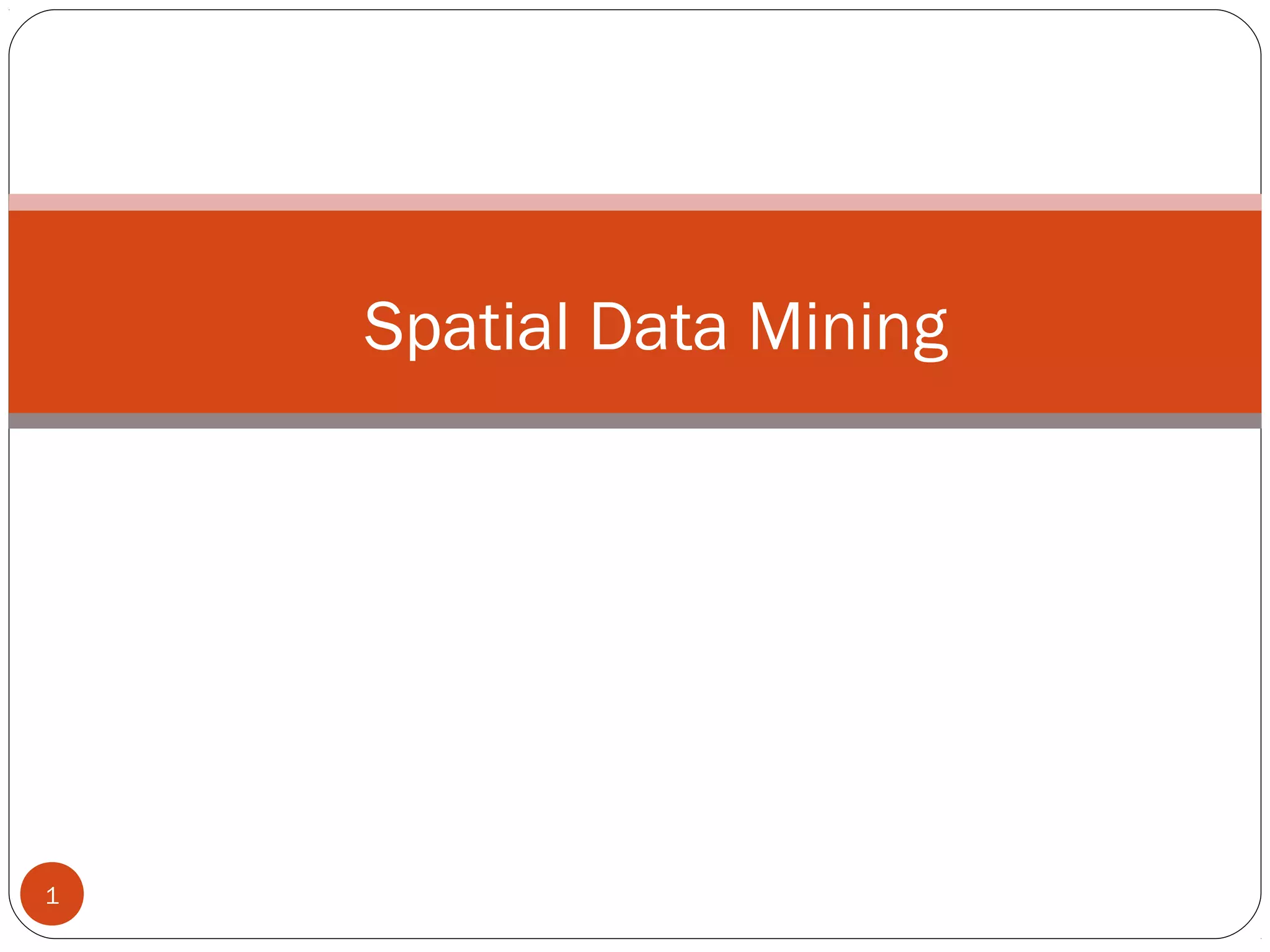

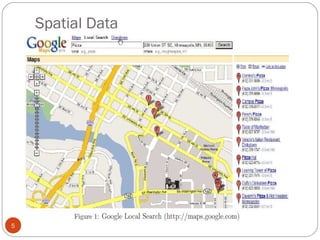

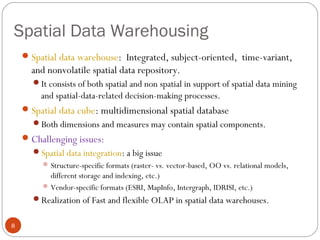

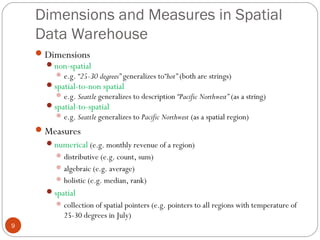

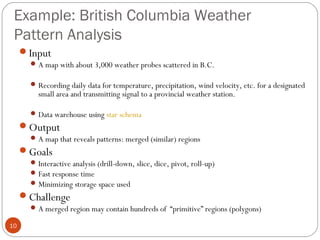

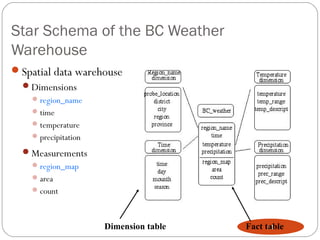

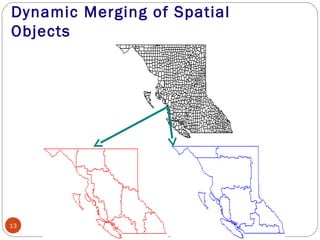

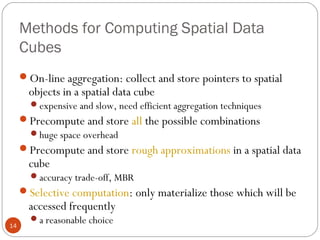

This document discusses spatial data mining and its applications. Spatial data mining involves extracting knowledge and relationships from large spatial databases. It can be used for applications like GIS, remote sensing, medical imaging, and more. Some challenges include the complexity of spatial data types and large data volumes. The document also covers topics like spatial data warehouses, dimensions and measures in spatial analysis, spatial association rule mining, and applications in fields such as earth science, crime mapping, and commerce.

![Mining Spatial Association and

Co-location Patterns

15

Spatial association rule: A ⇒ B [s%, c%]

A and B are sets of spatial or non-spatial predicates

Topological relations: intersects, overlaps, disjoint, etc.

Spatial orientations: left_of, west_of, under, etc.

Distance information: close_to, within_distance, etc.

s% is the support and c% is the confidence of the rule

Examples

is_a(x, “School”) ^ Close_to(x, “Sports_Center”) → close_to(x, “Park”)

[7%, 85%]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-150507082511-lva1-app6892/85/4-2-spatial-data-mining-15-320.jpg)