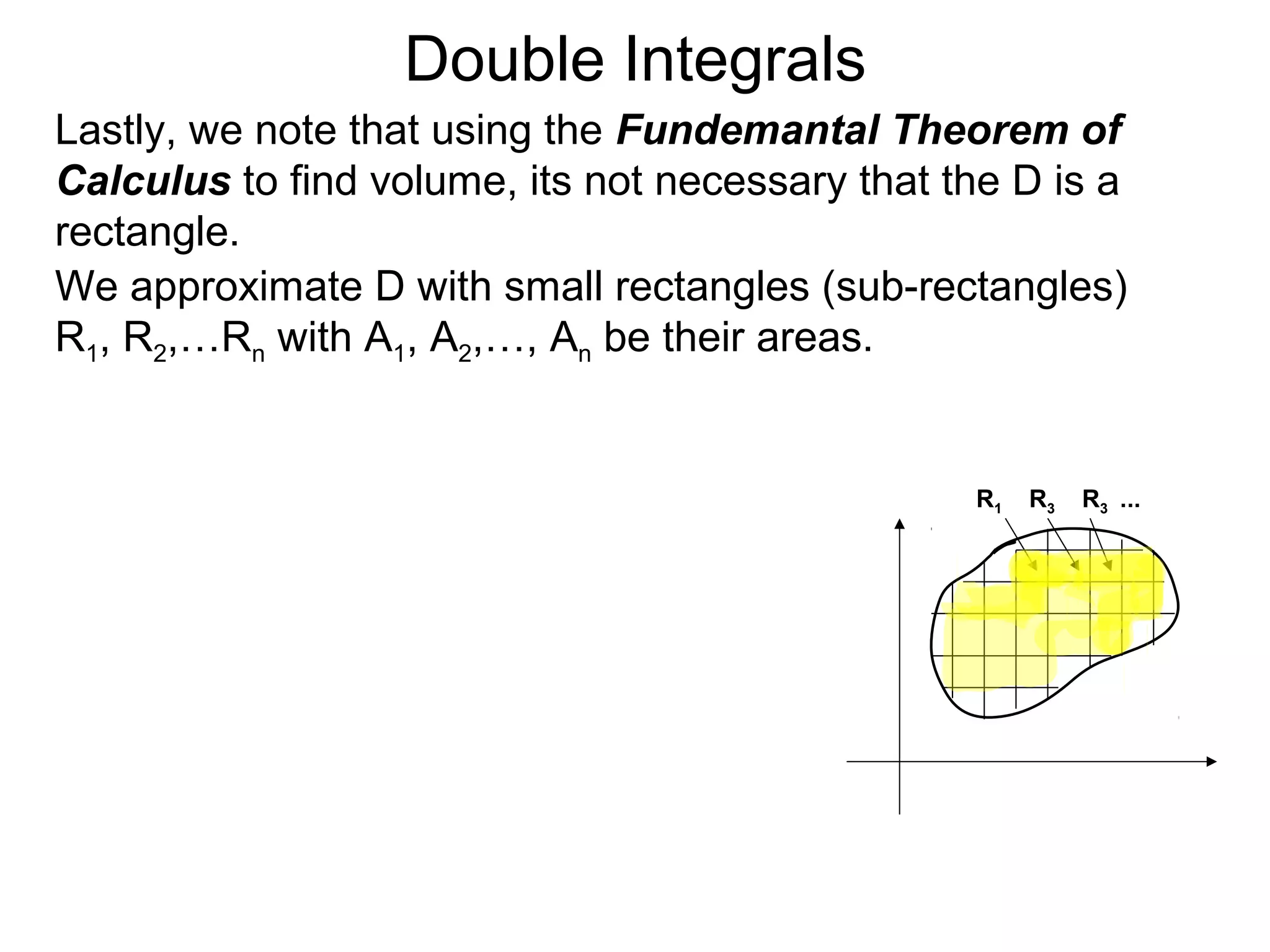

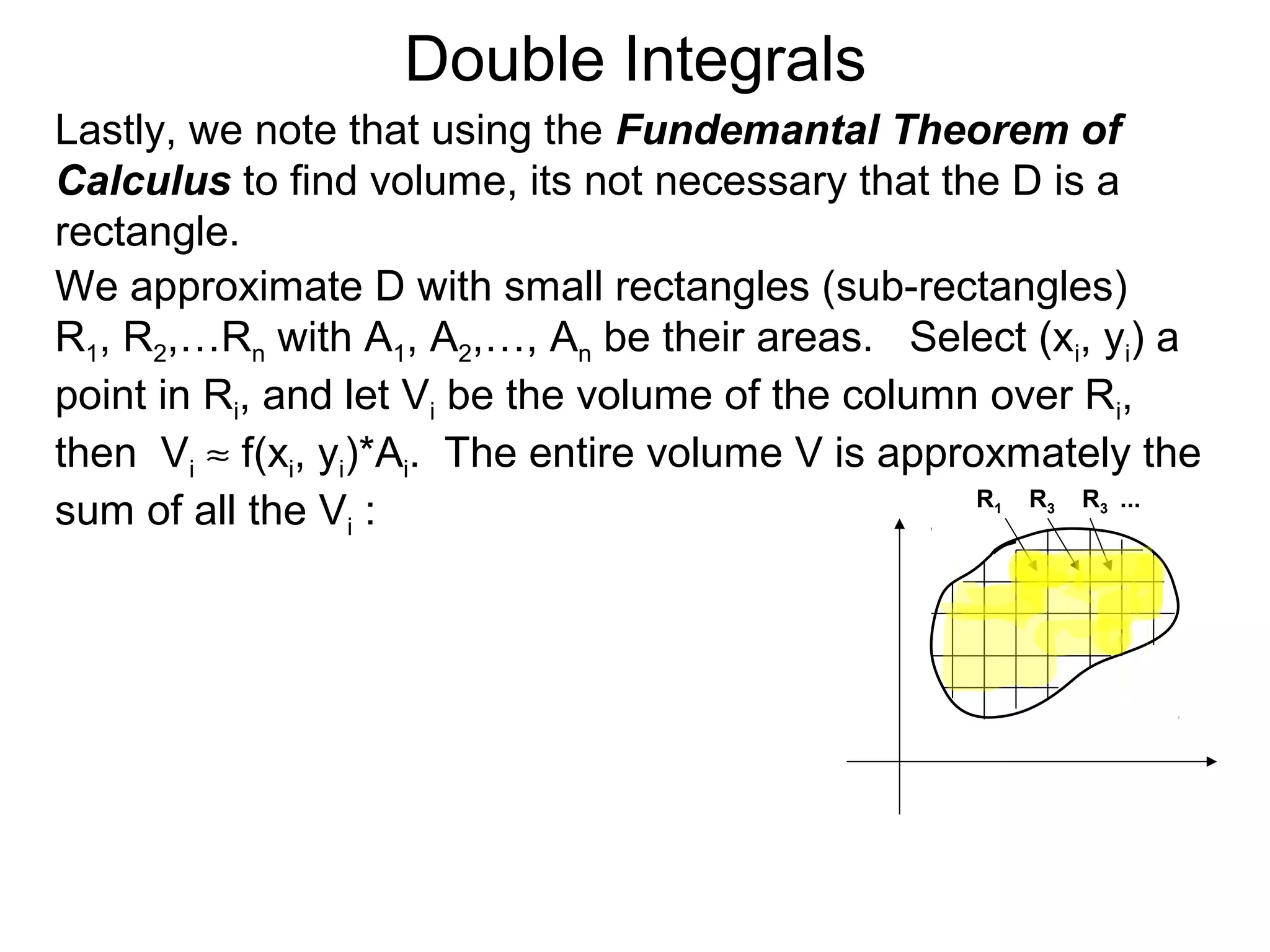

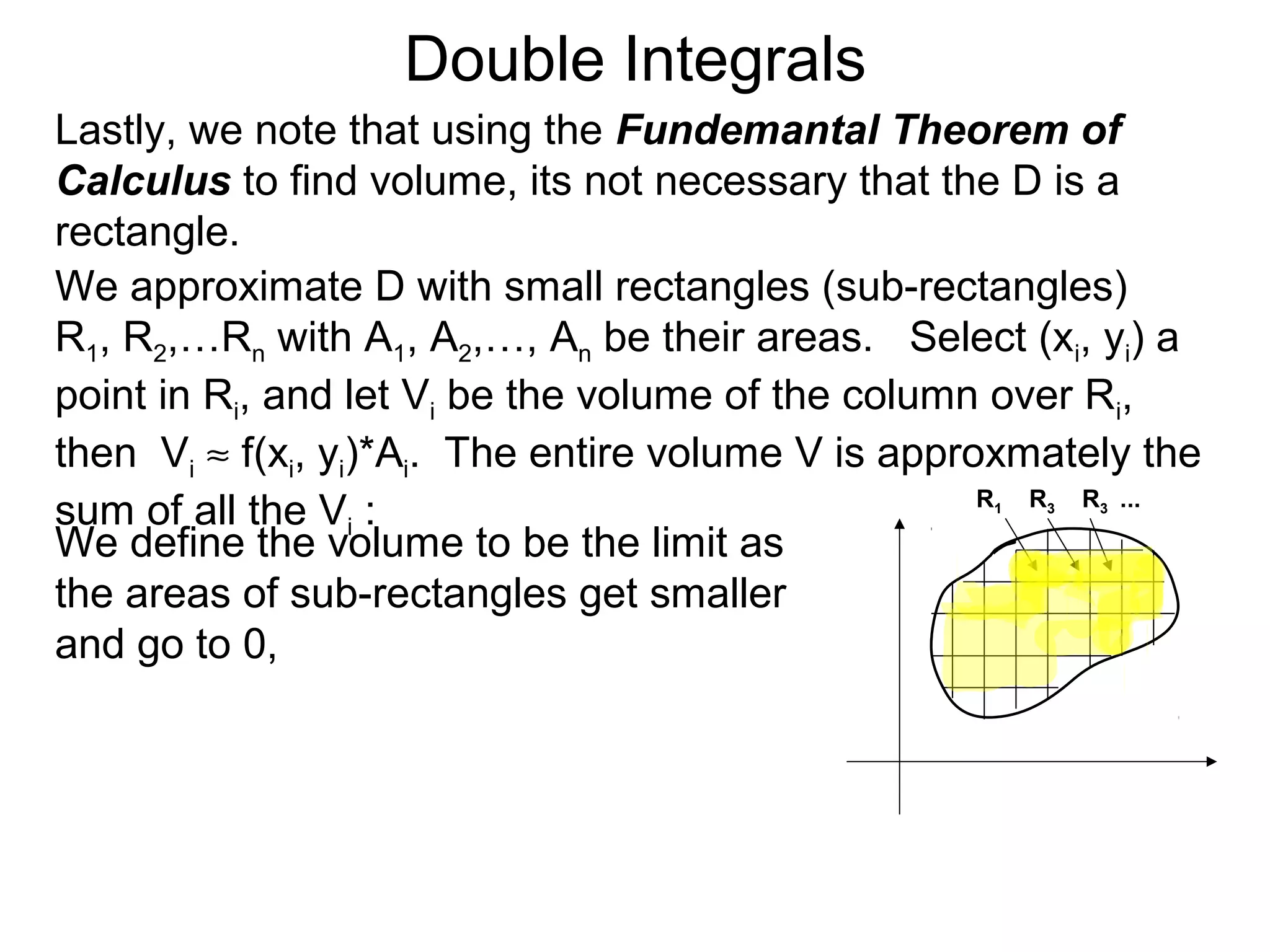

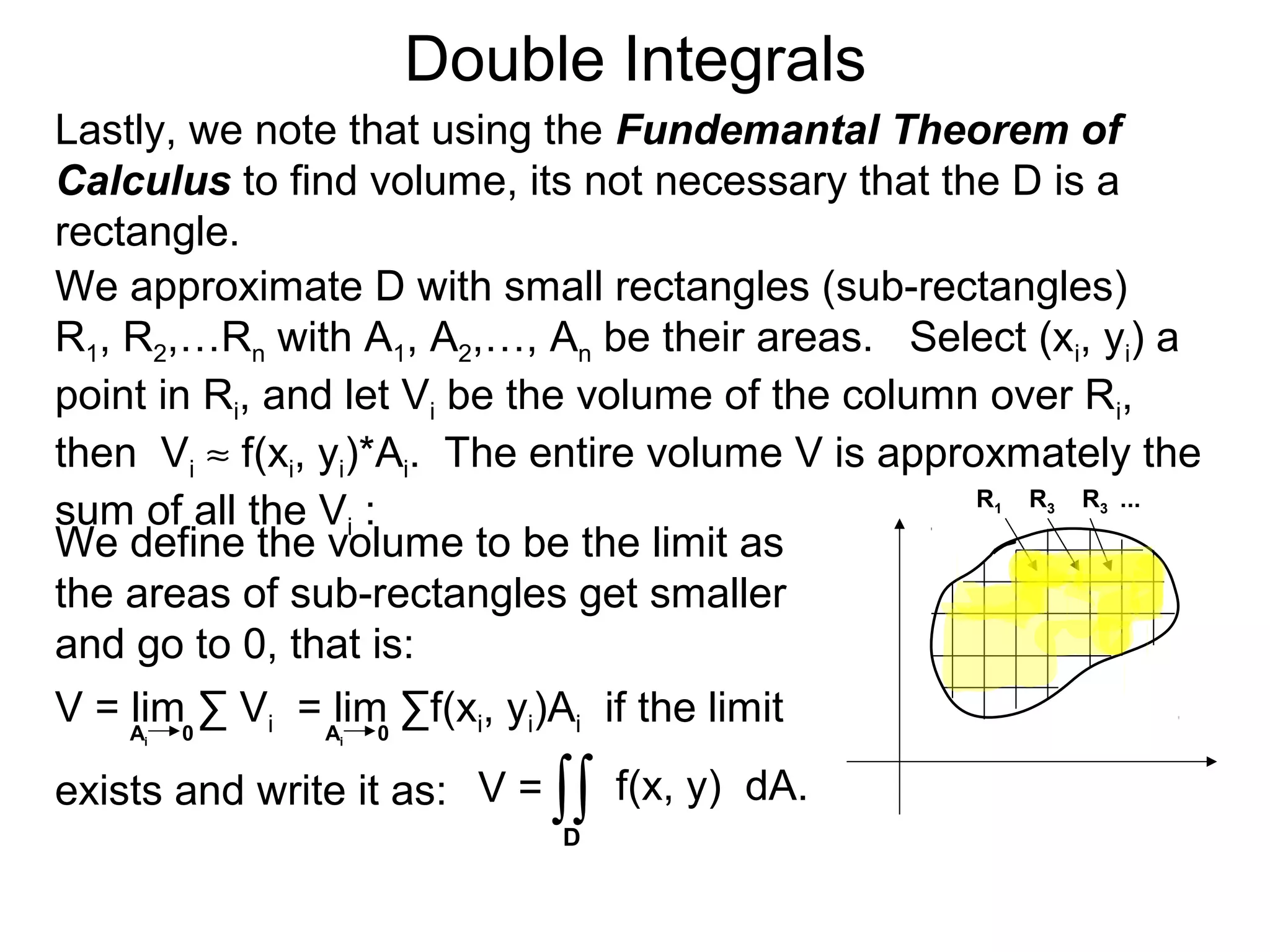

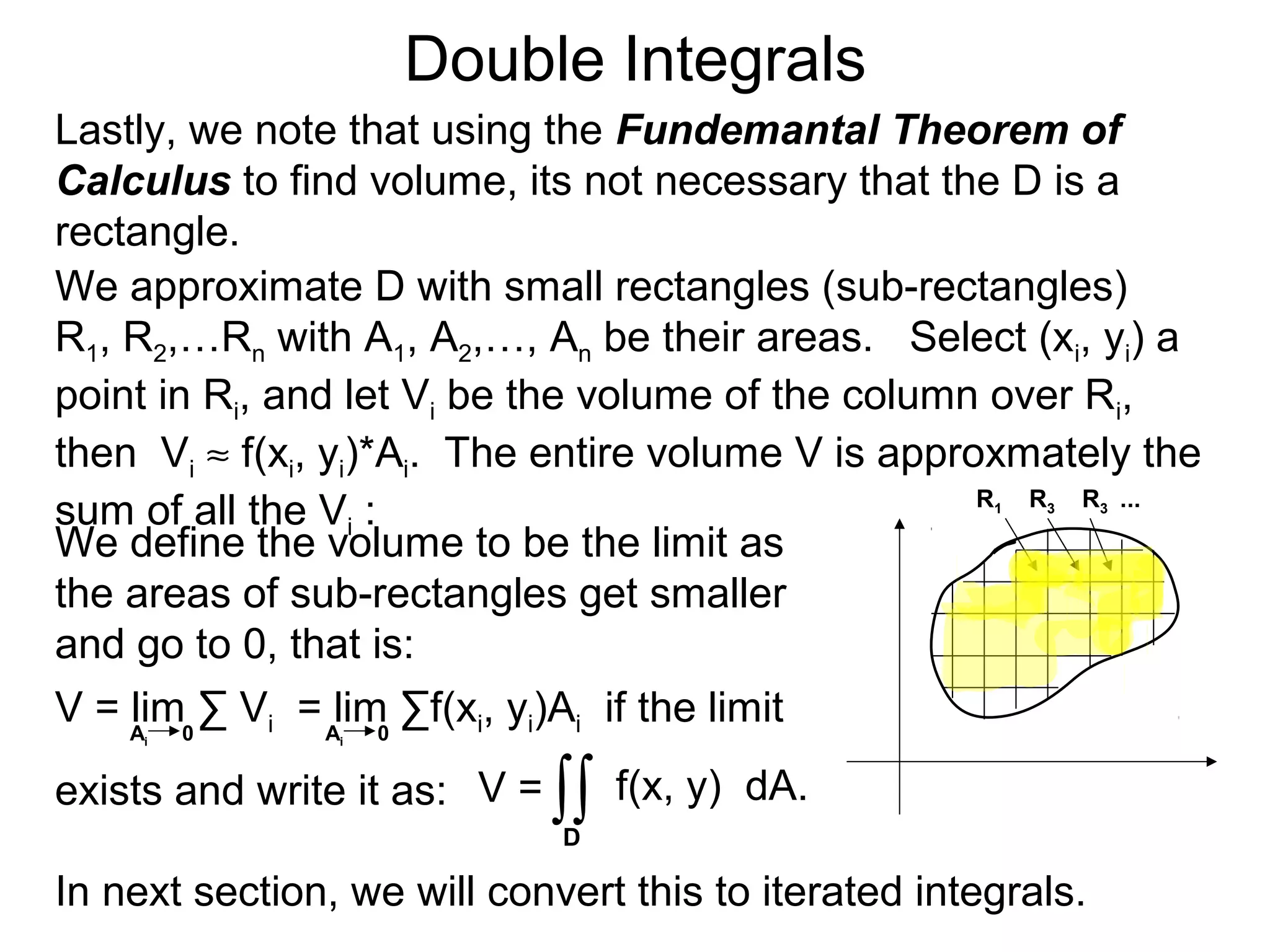

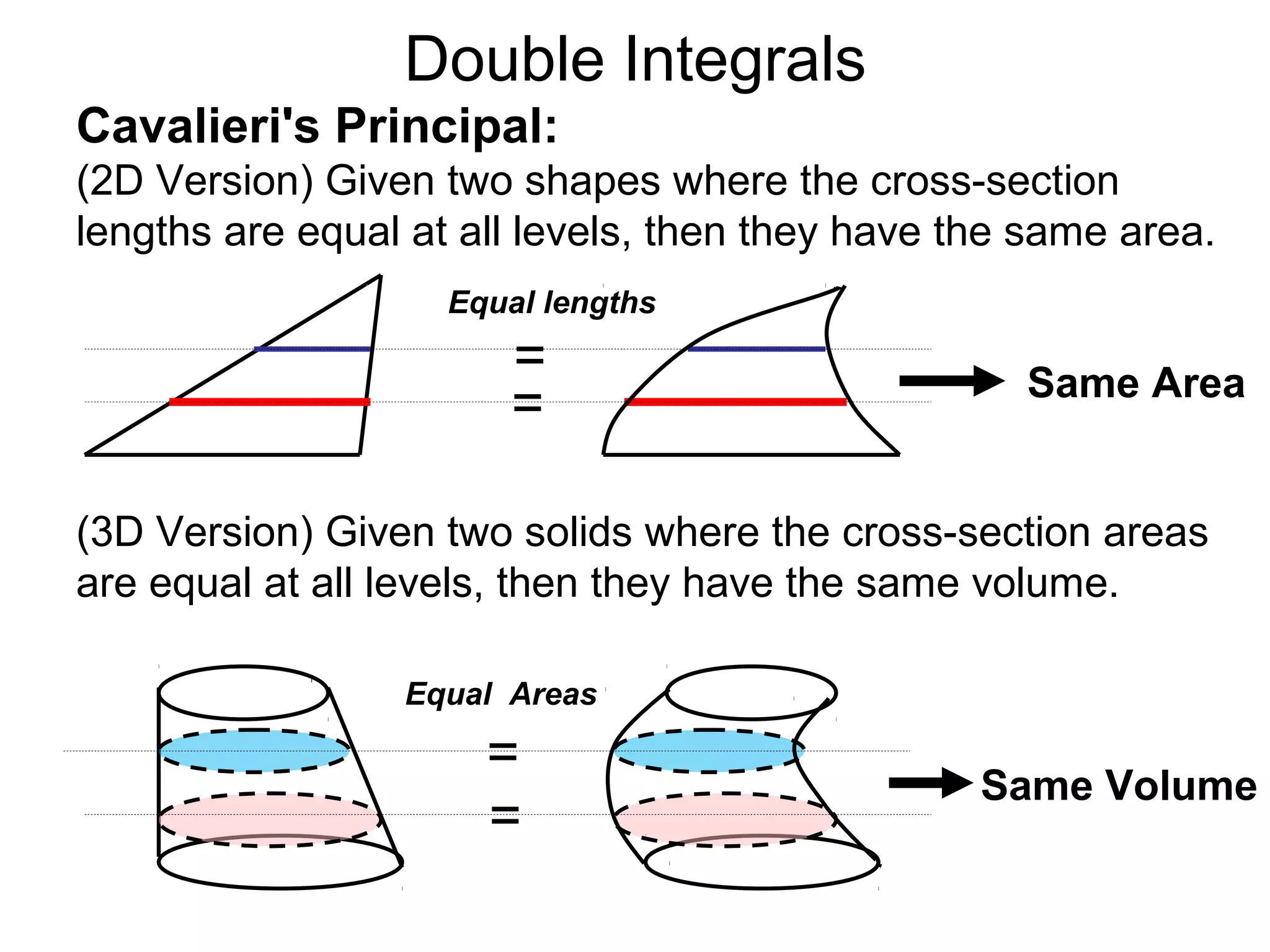

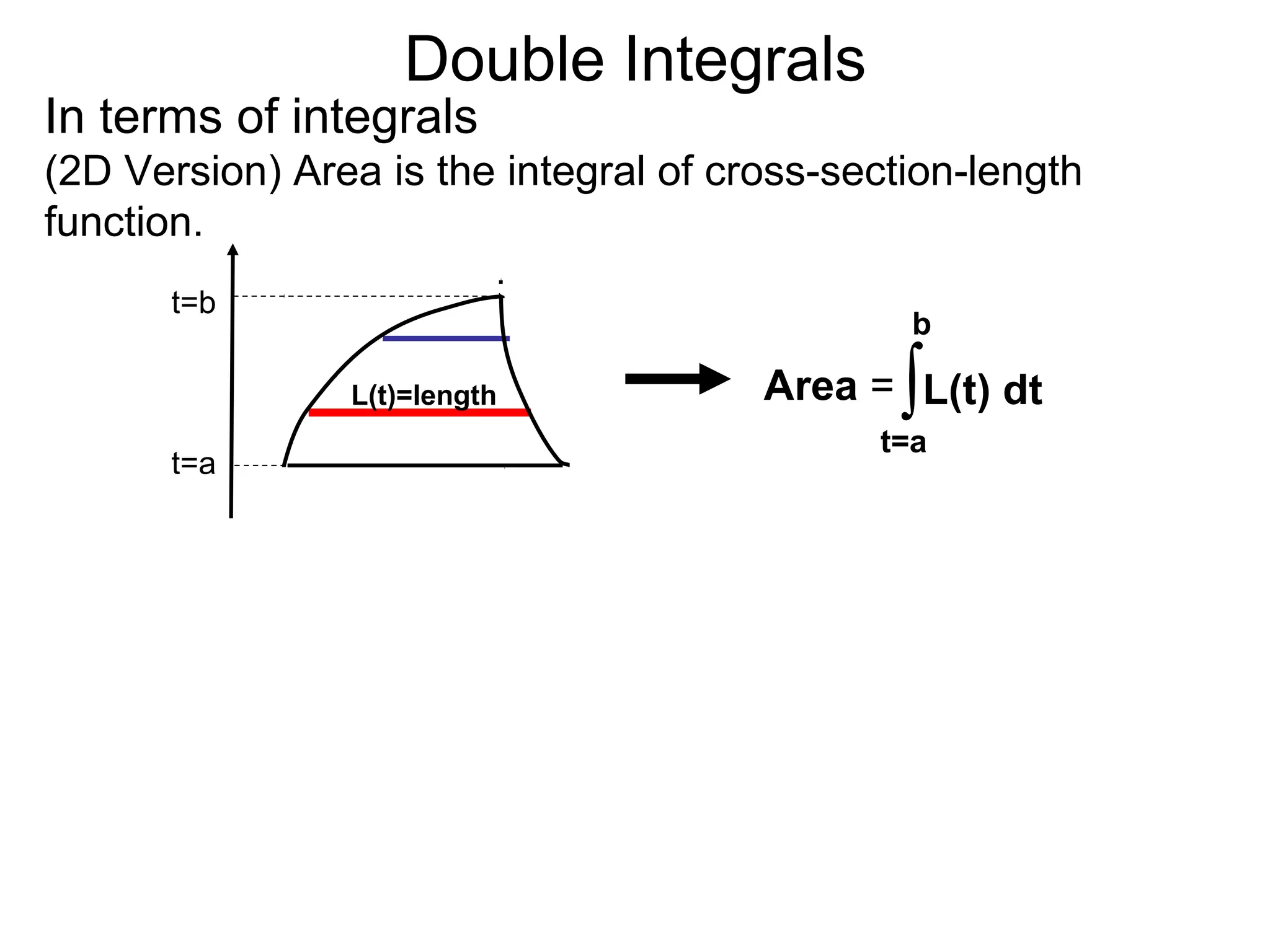

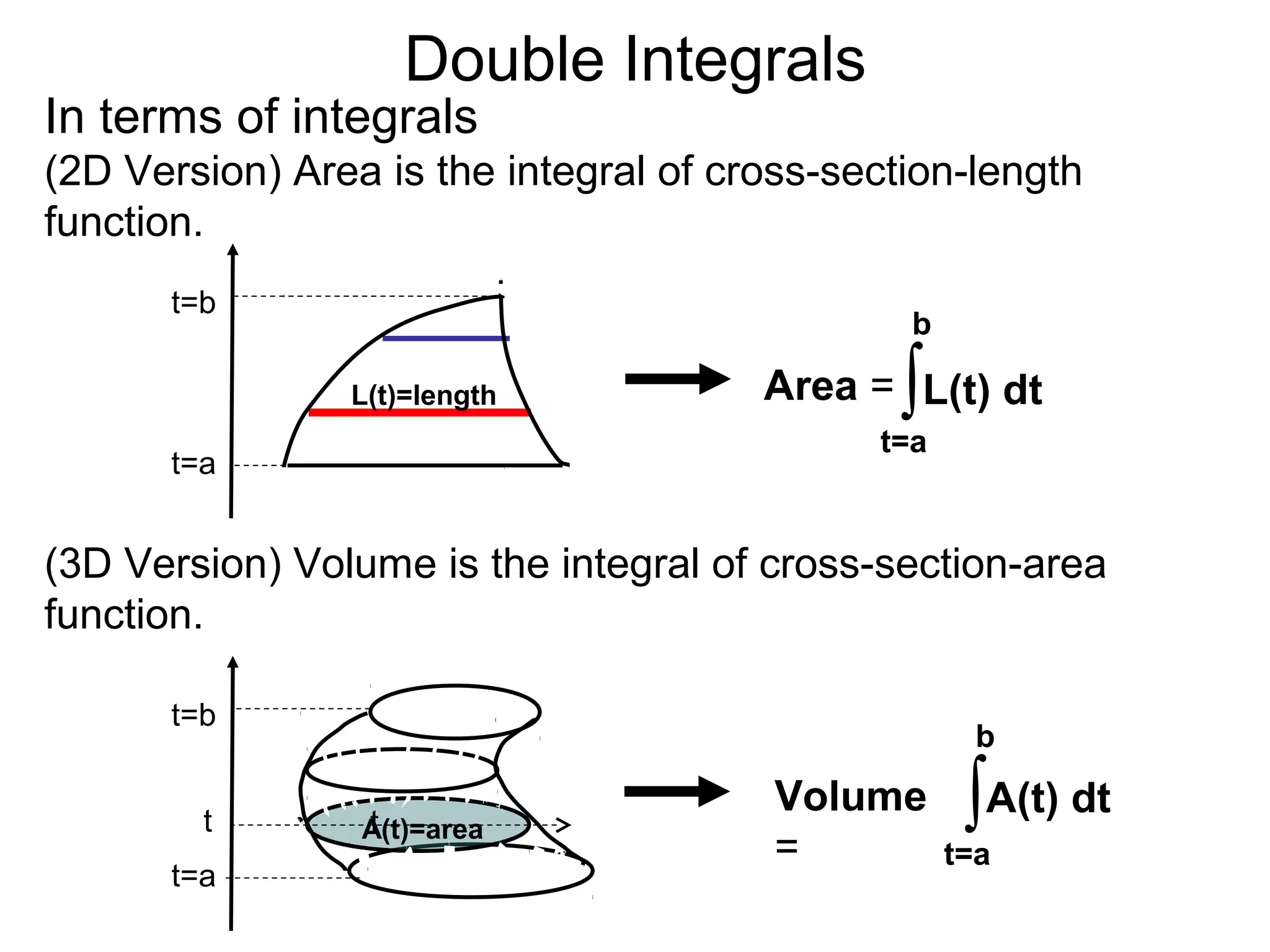

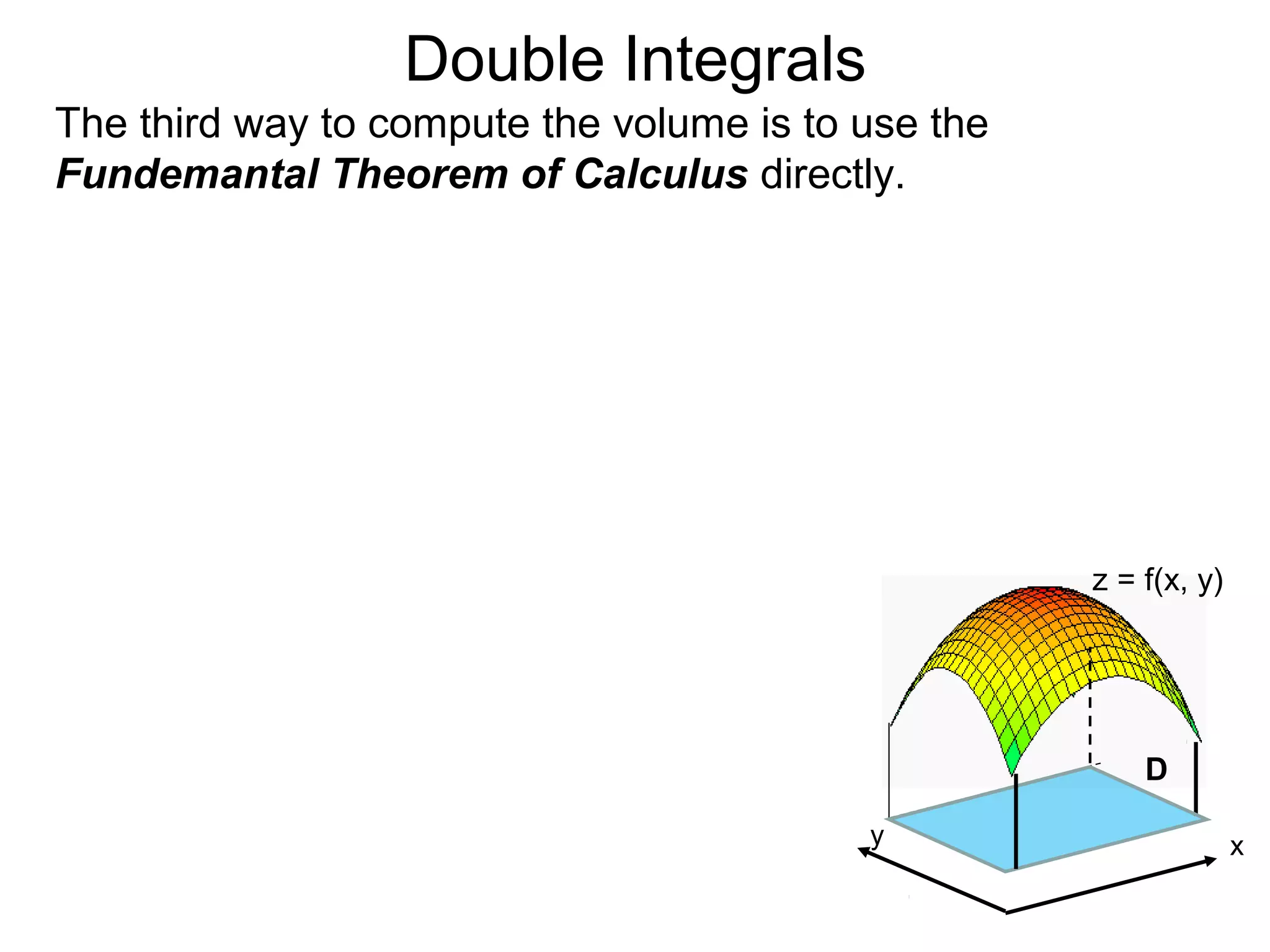

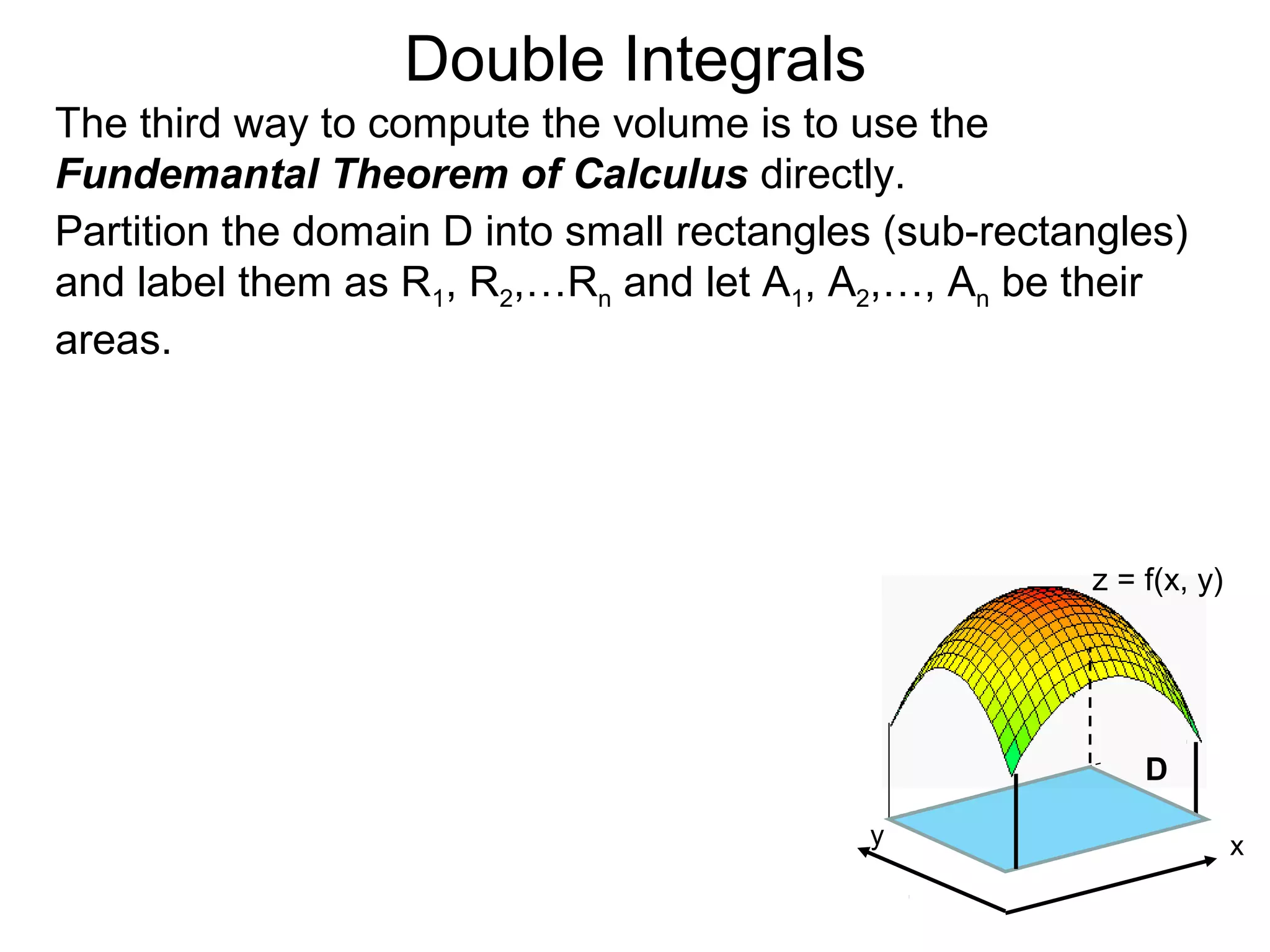

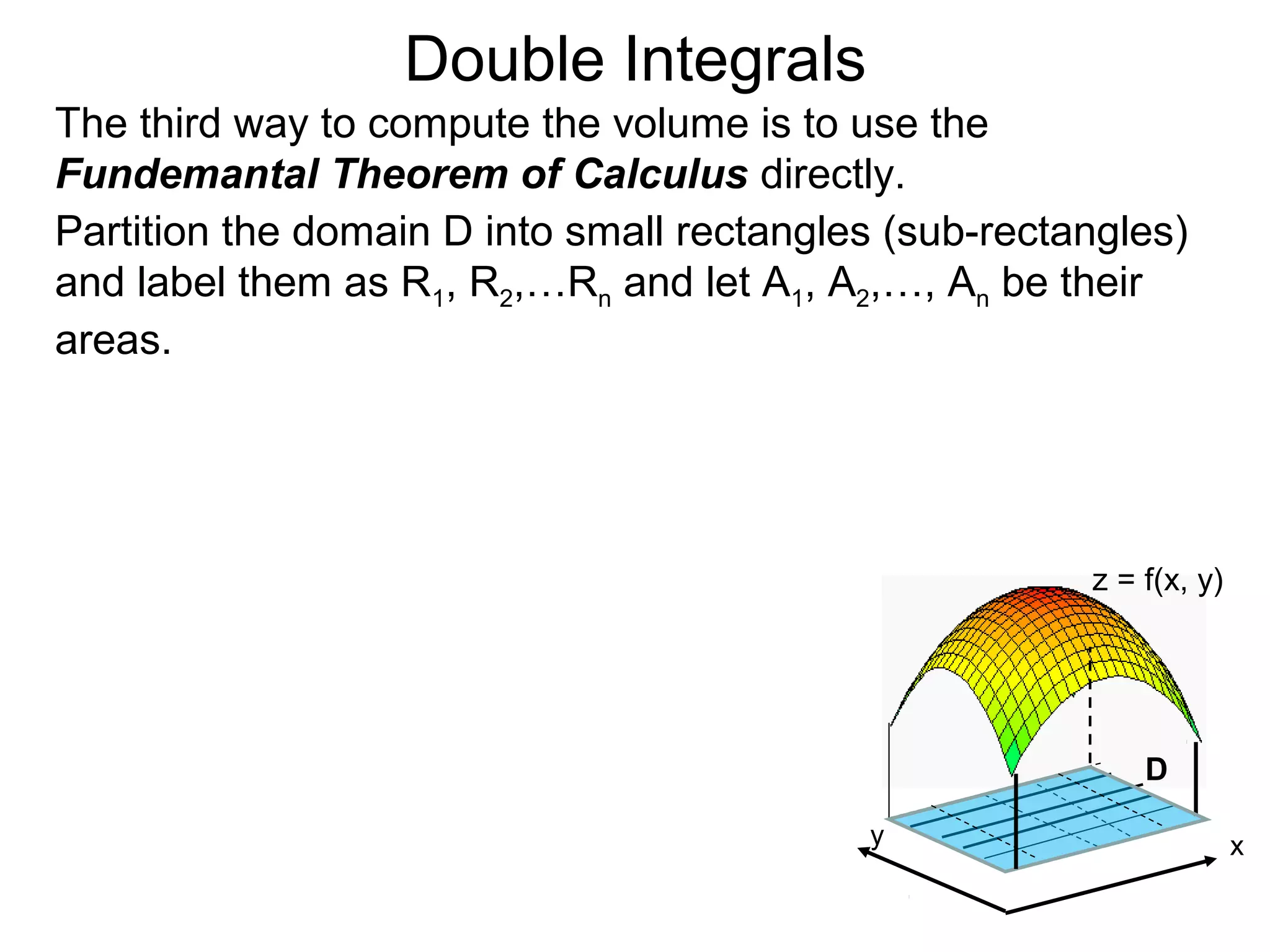

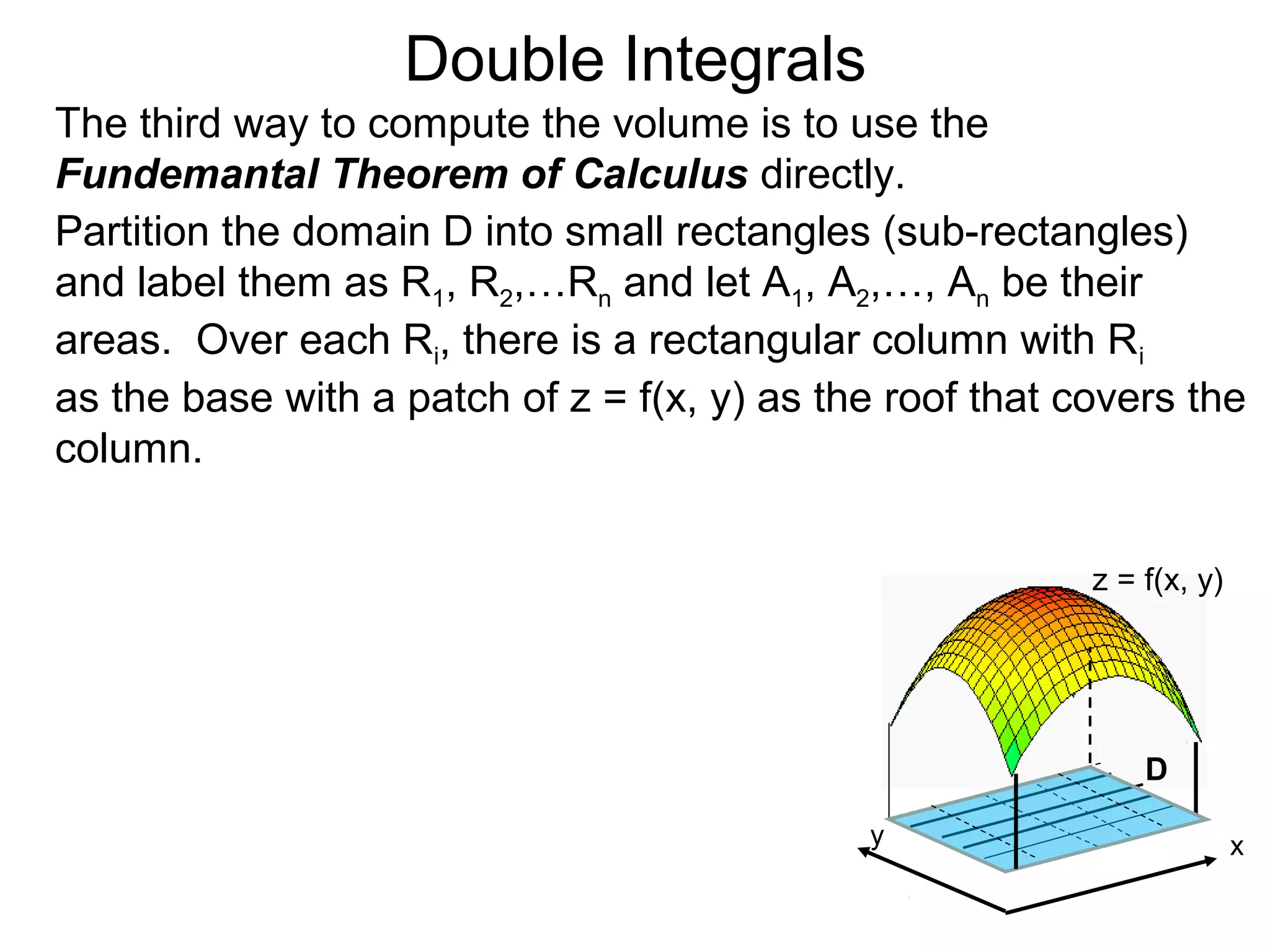

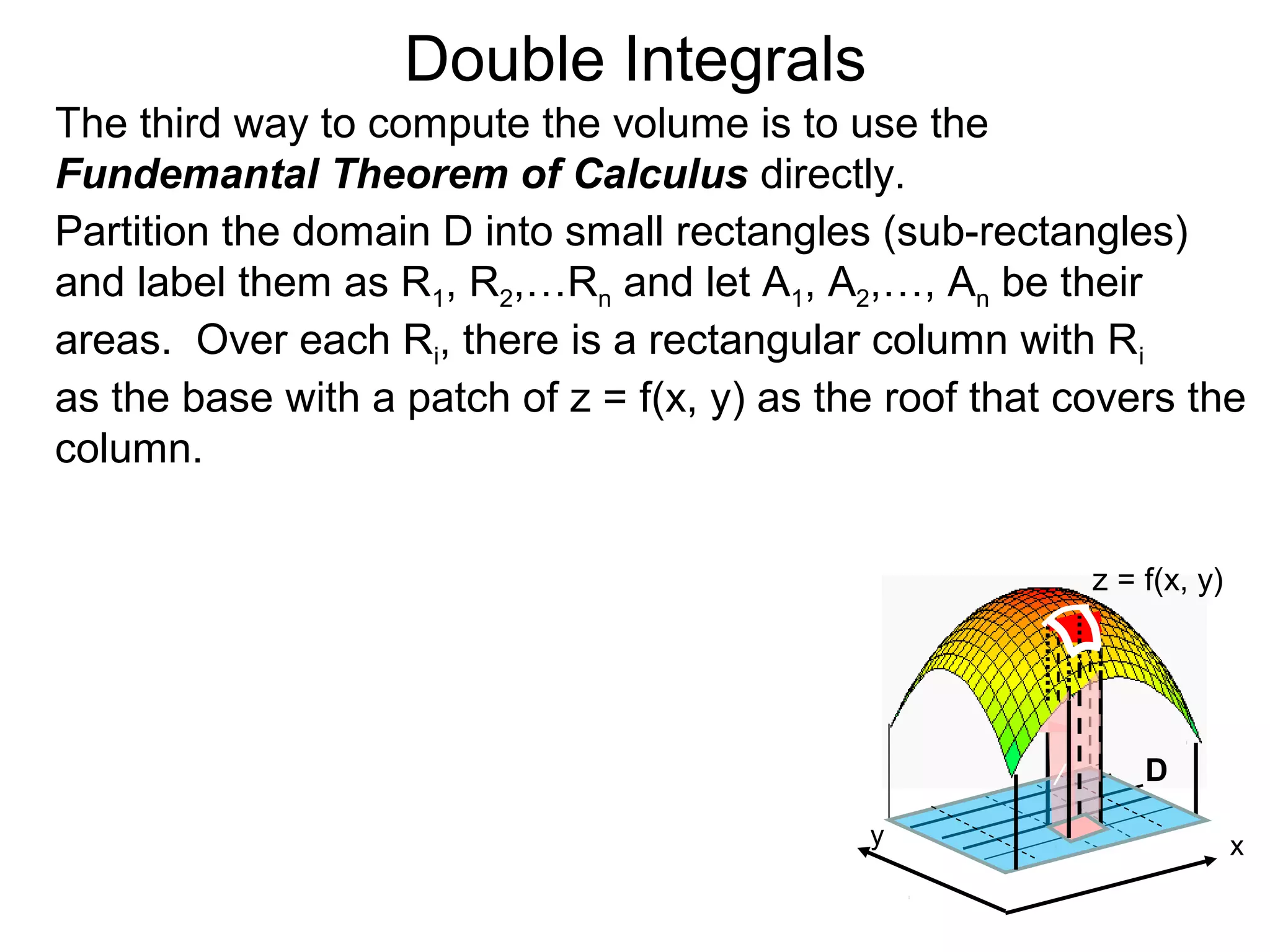

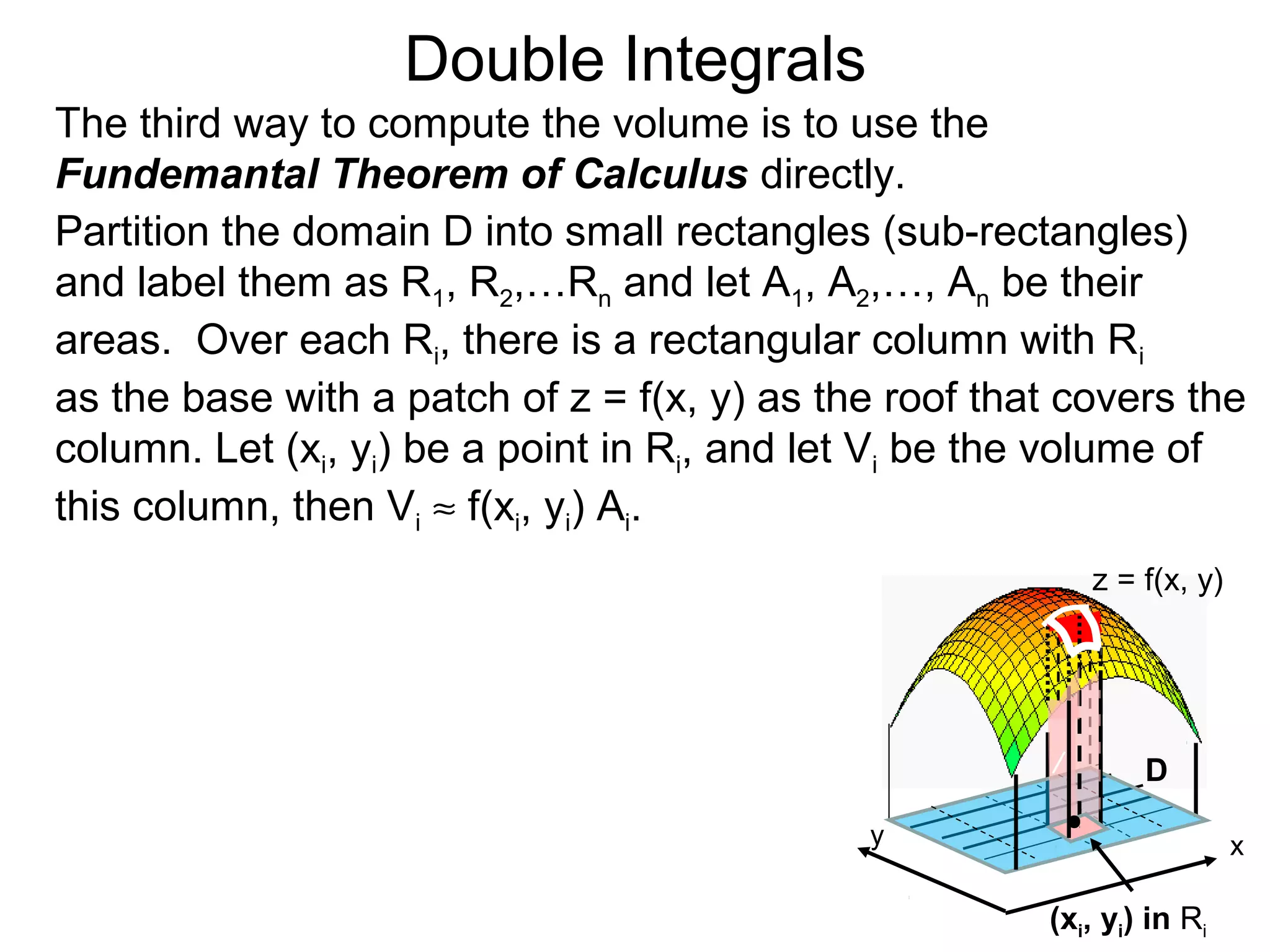

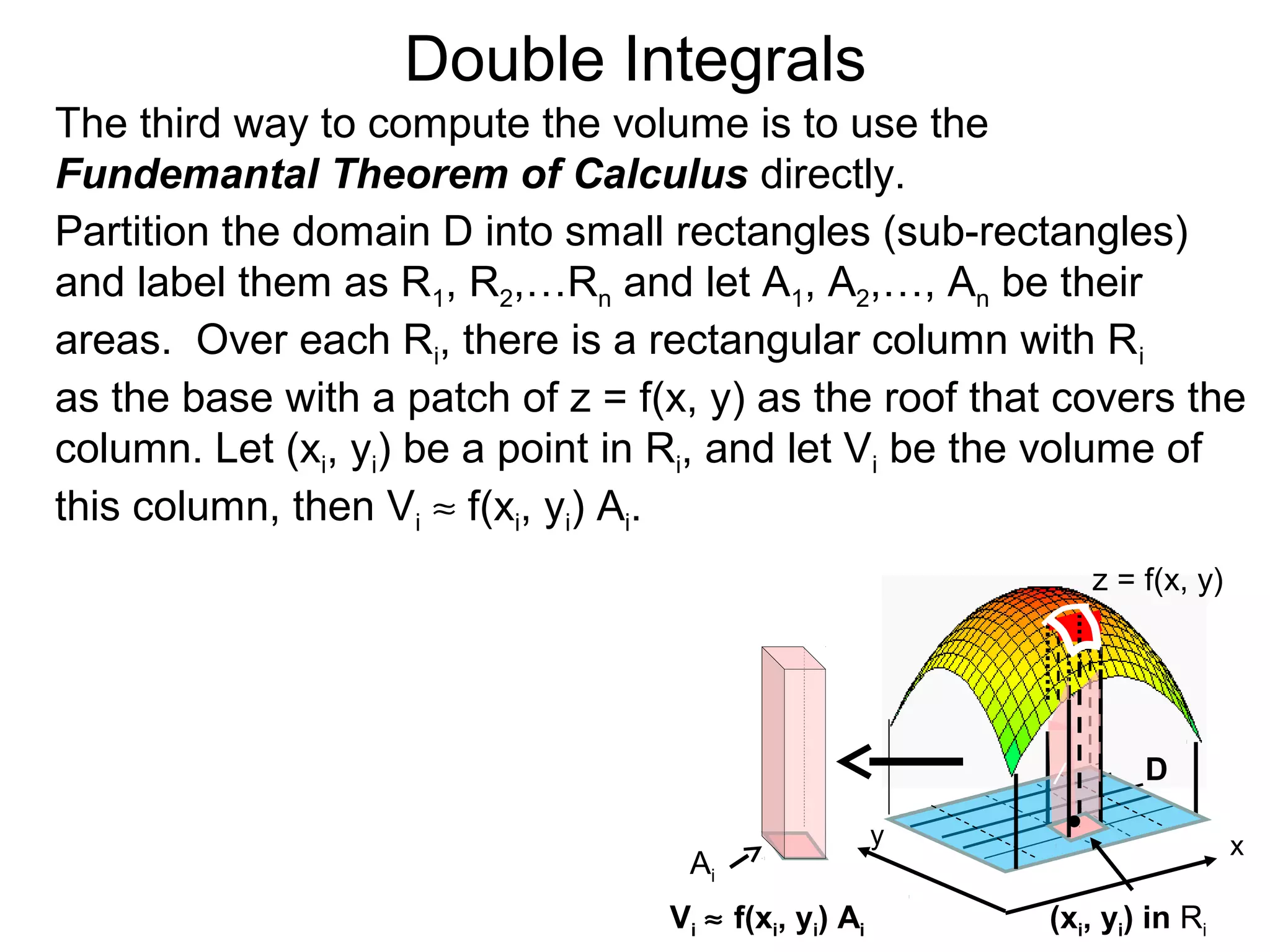

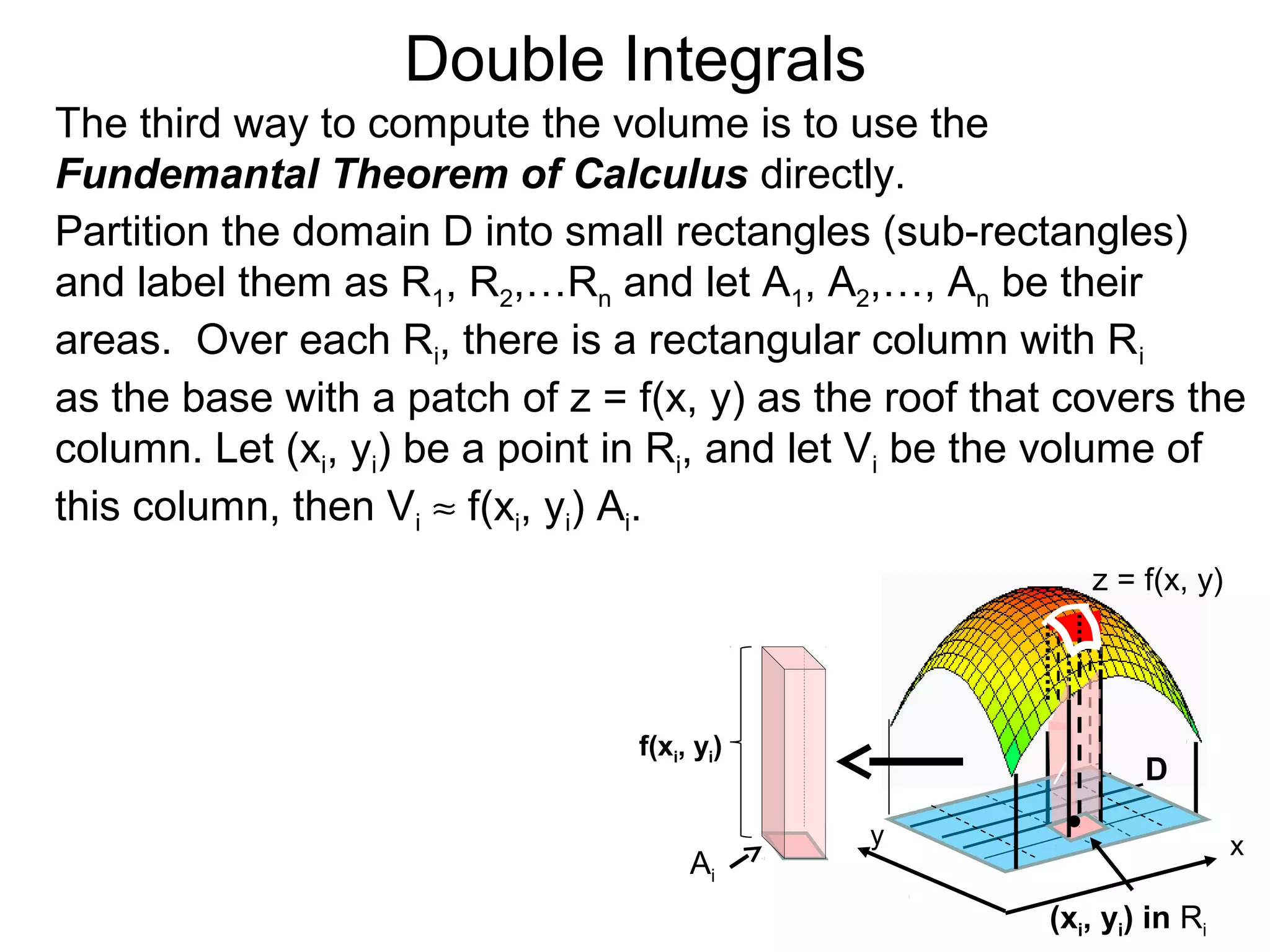

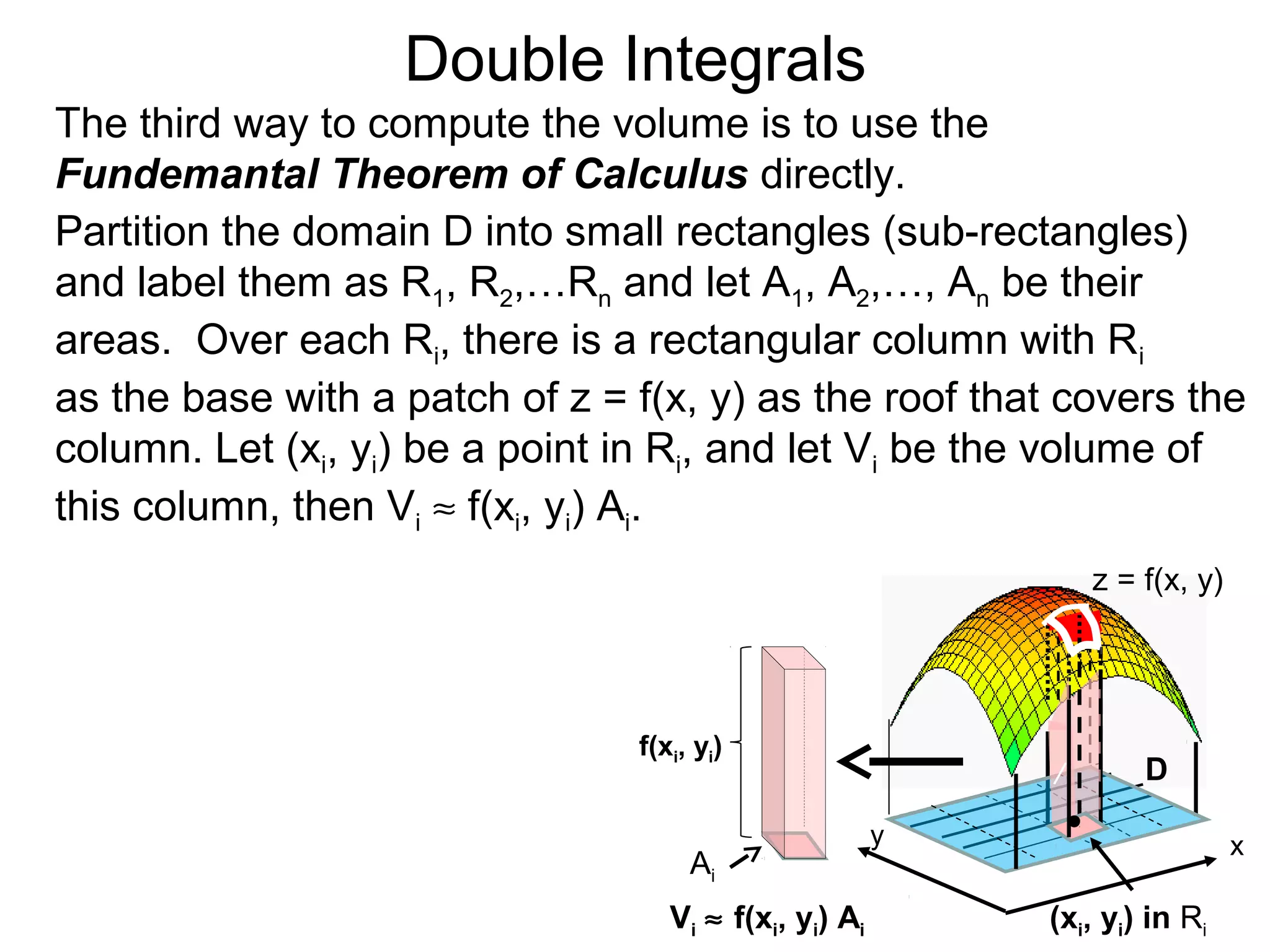

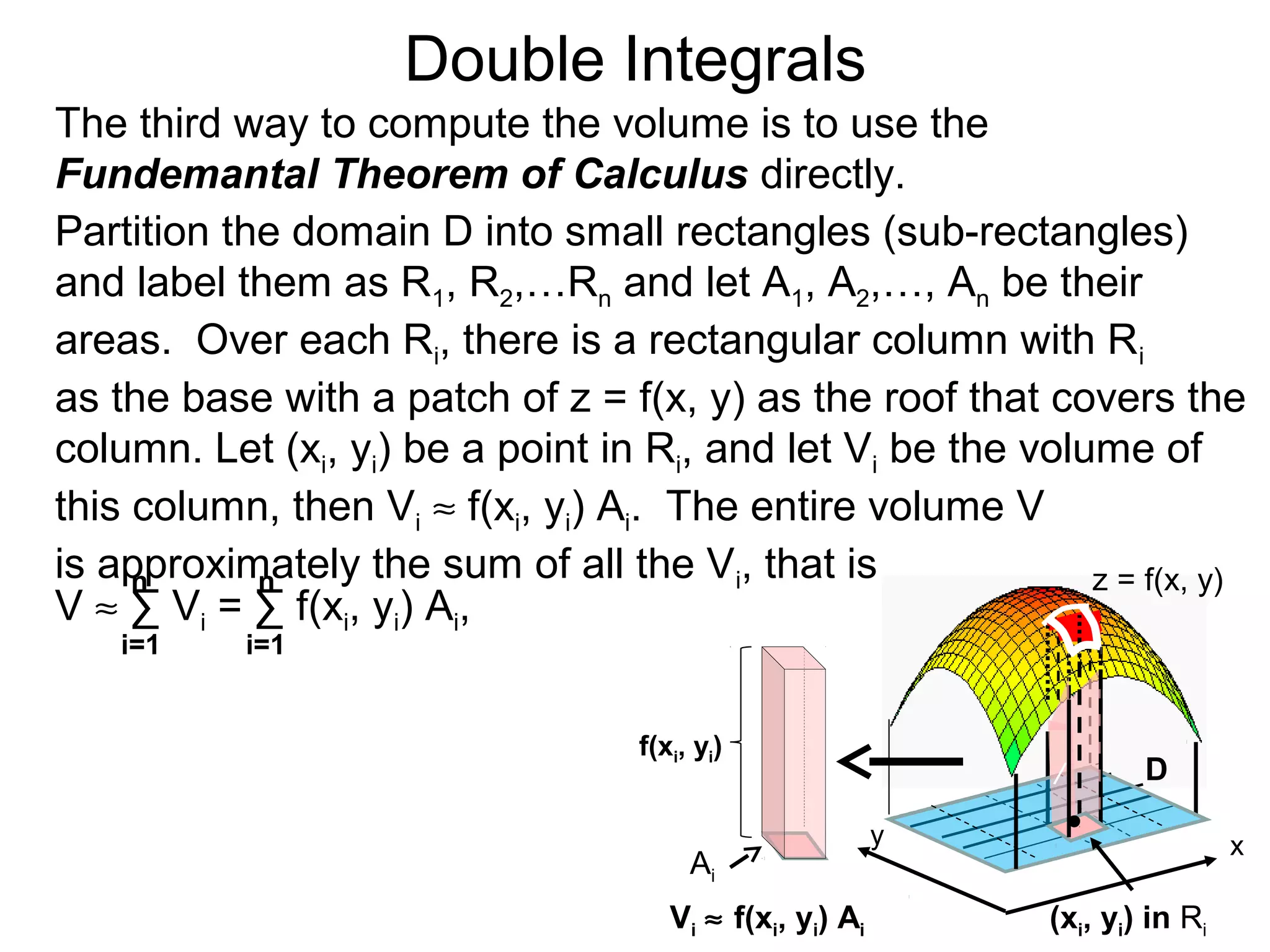

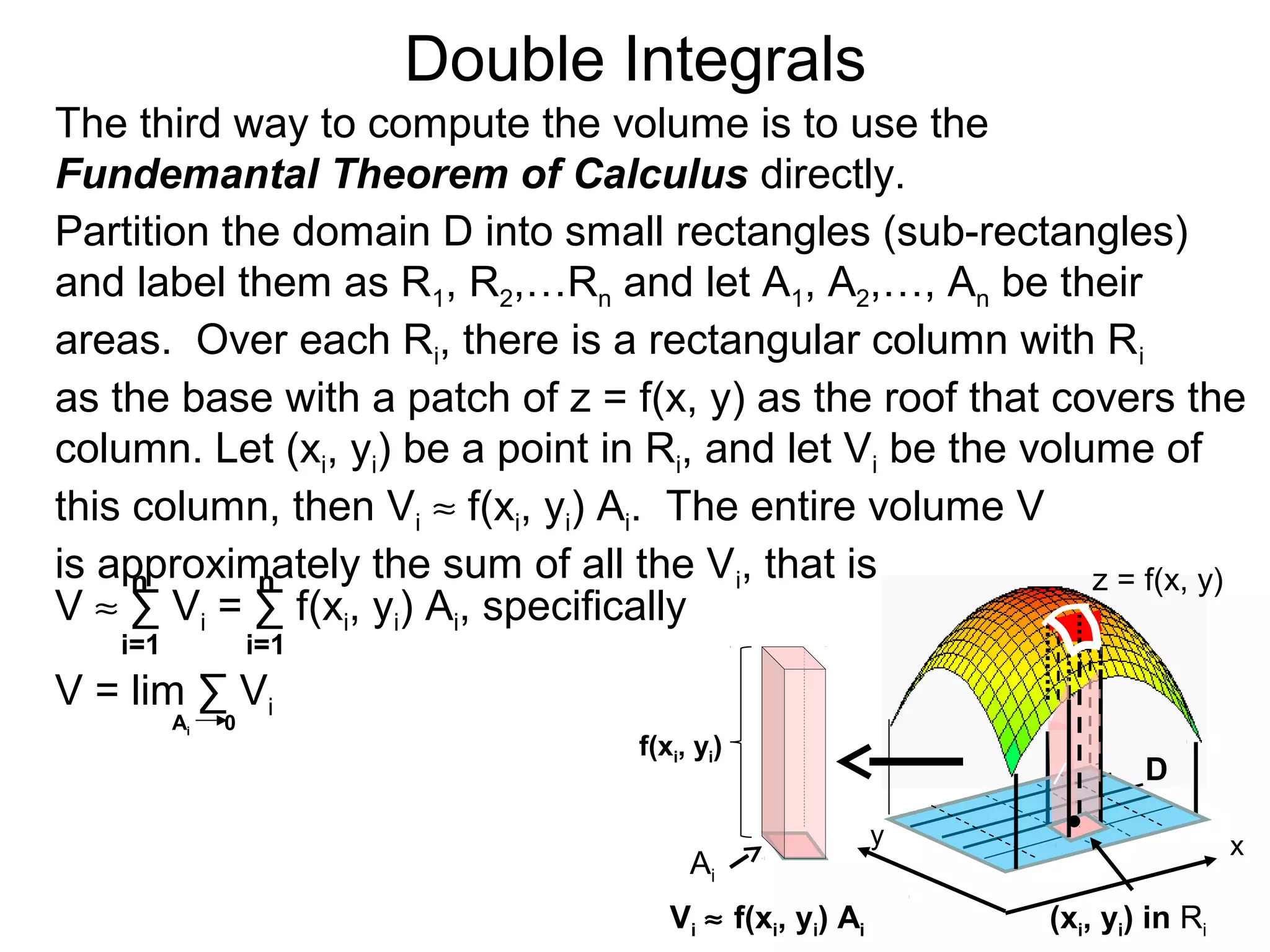

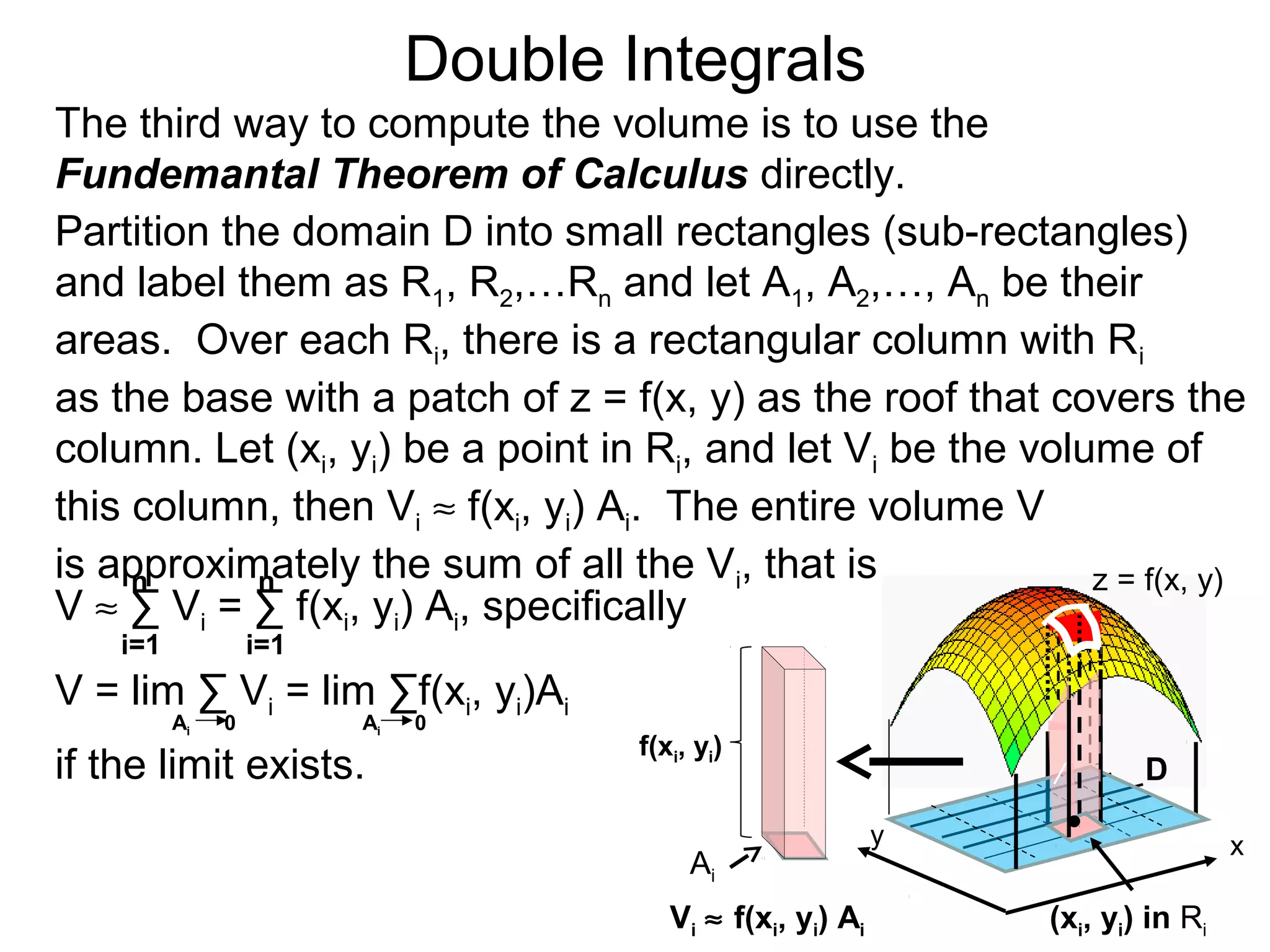

The document discusses double integrals and their use in calculating volumes. It explains that double integrals allow calculating the volume of a solid over a domain D by integrating the height function f(x,y) over D. Three methods are provided: integrating cross-sectional areas A(x) or A(y) with respect to x or y; directly using the fundamental theorem of calculus by partitioning D into subrectangles and summing the approximate volumes; and writing the calculation as a double integral of f(x,y) over D.

![Double Integrals

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d]. a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-6-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Given z = f(x, y) ≥ 0 over the domain D = [a, b] x [c, d],

it defines a solid over D.

x

y

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d].

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]

D](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-7-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Given z = f(x, y) ≥ 0 over the domain D = [a, b] x [c, d],

it defines a solid over D. Hence the volume V of this solid is

x

y

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d].

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]

D

x=a

b

A(x) dx, where A(x) is the cross-sectional area

function.

V = ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-8-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Given z = f(x, y) ≥ 0 over the domain D = [a, b] x [c, d],

it defines a solid over D. Hence the volume V of this solid is

x

y

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d].

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]

A(x)

D

x=a

b

A(x) dx, where A(x) is the cross-sectional area

function.

V = ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-9-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Given z = f(x, y) ≥ 0 over the domain D = [a, b] x [c, d],

it defines a solid over D. Hence the volume V of this solid is

x

y

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d].

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]

A(x)

D

x=a

b

A(x) dx, where A(x) is the cross-sectional area

function.

V =

d

∫

On the other hand A(x) =

y=c

f(x, y) dy

where the integral is taken by

treating x as a constant.

∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-10-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Given z = f(x, y) ≥ 0 over the domain D = [a, b] x [c, d],

it defines a solid over D. Hence the volume V of this solid is

x

y

We write the rectangular area

{(x, y)| a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ y ≤ d}

as [a, b] x [c, d].

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

Hence the volume V is

V = [

x=a

x=b

dx.

y=c

y=d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫

a b

c

d

[a, b] x [c, d]

A(x)

D

x=a

b

A(x) dx, where A(x) is the cross-sectional area

function.

V =

d

∫

On the other hand A(x) =

y=c

f(x, y) dy

where the integral is taken by

treating x as a constant.

∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-11-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

A(x)

D

f(x, y) dy ] dxThe integral

is called the double integral with respect to y then x.

f(x, y) dy dx =∫∫ ∫ ∫[ A(x) dx∫=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-12-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

A(x)

D

f(x, y) dy ] dxThe integral

is called the double integral with respect to y then x.

f(x, y) dy dx =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

f(x, y) dx ] dySimilarly,

is called the double integral with respect to x then y.

f(x, y) dx dy =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

A(x) dx∫=

A(y) dy∫=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-13-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

A(x)

D

f(x, y) dy ] dxThe integral

is called the double integral with respect to y then x.

f(x, y) dy dx =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

y

A(y)

f(x, y) dx ] dySimilarly,

is called the double integral with respect to x then y.

f(x, y) dx dy =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

It represents the volume integration over the cross sectional

areas A(y) by setting y as a constant

A(x) dx∫=

A(y) dy∫=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-14-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

x

A(x)

D

f(x, y) dy ] dxThe integral

is called the double integral with respect to y then x.

f(x, y) dy dx =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

x

y

z = f(x, y)

a

b

c

d

D

y

A(y)

f(x, y) dx ] dySimilarly,

is called the double integral with respect to x then y.

f(x, y) dx dy =∫∫ ∫ ∫[

f(x, y) dx = A(y)∫ is calculated by treating y as a constant.

It represents the volume integration over the cross sectional

areas A(y) by setting y as a constant and that

A(x) dx∫=

A(y) dy∫=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-15-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-30-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

[

x=a

b

dy

y=c

d

f(x, y) dx ]∫∫V = f(x, y) dA =∫∫D

= [

x=a

b

dx

y=c

d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-31-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

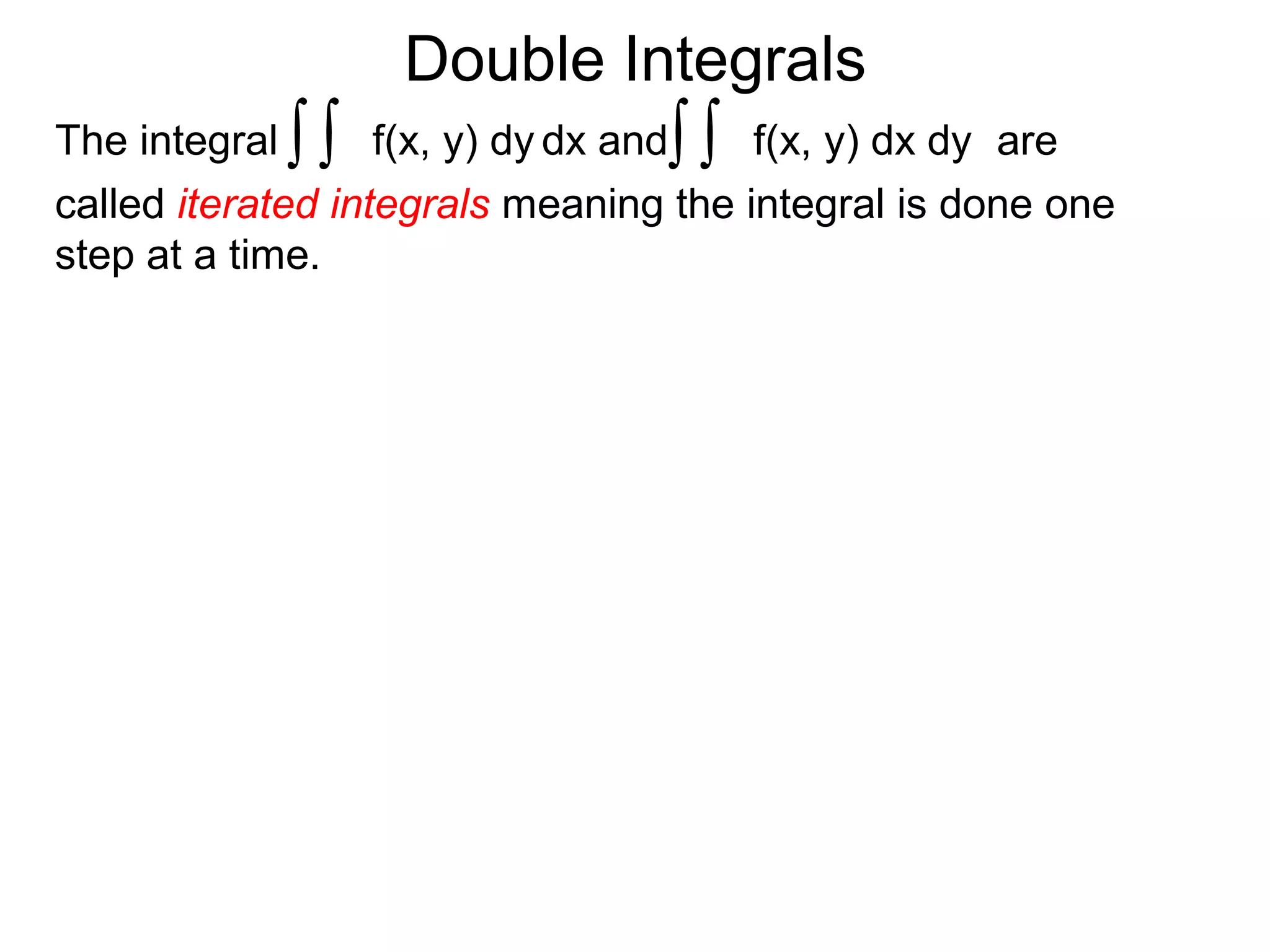

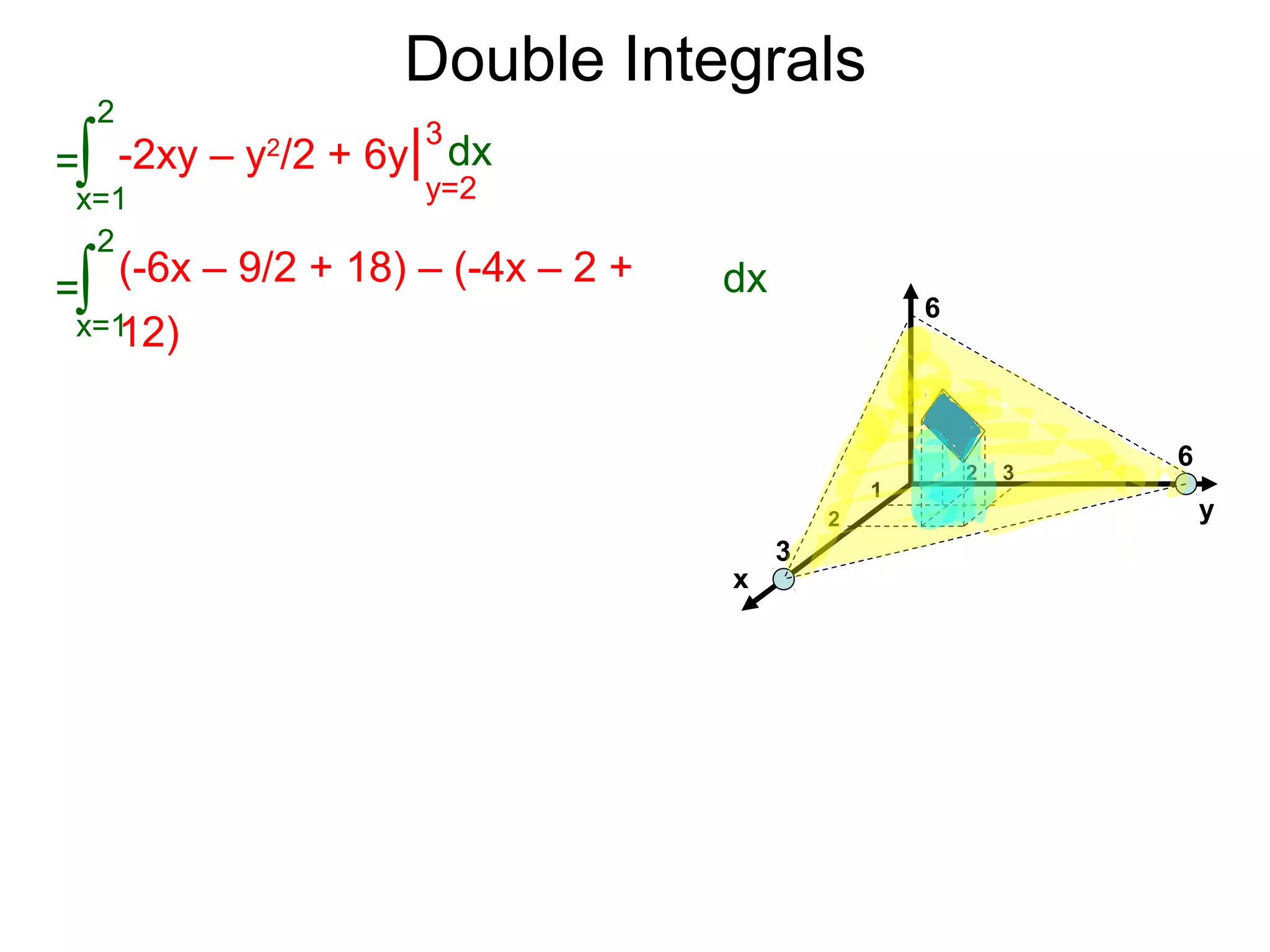

Example: Fid the volume of z = f(x, y) = -2x – y + 6 over the

domain [1, 2] x [2, 3]

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.

[

x=a

b

dy

y=c

d

f(x, y) dx ]∫∫V = f(x, y) dA =∫∫D

= [

x=a

b

dx

y=c

d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-32-2048.jpg)

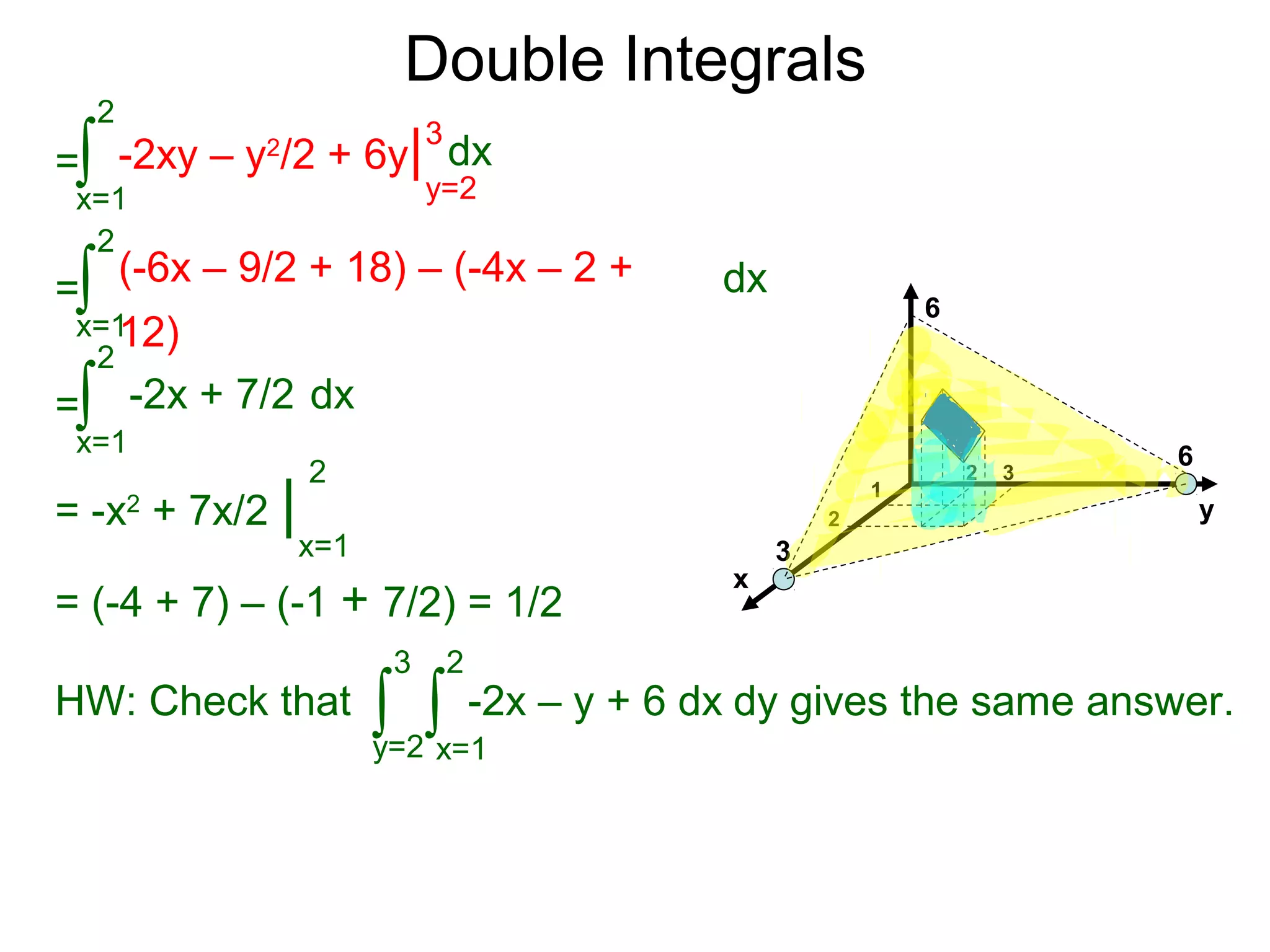

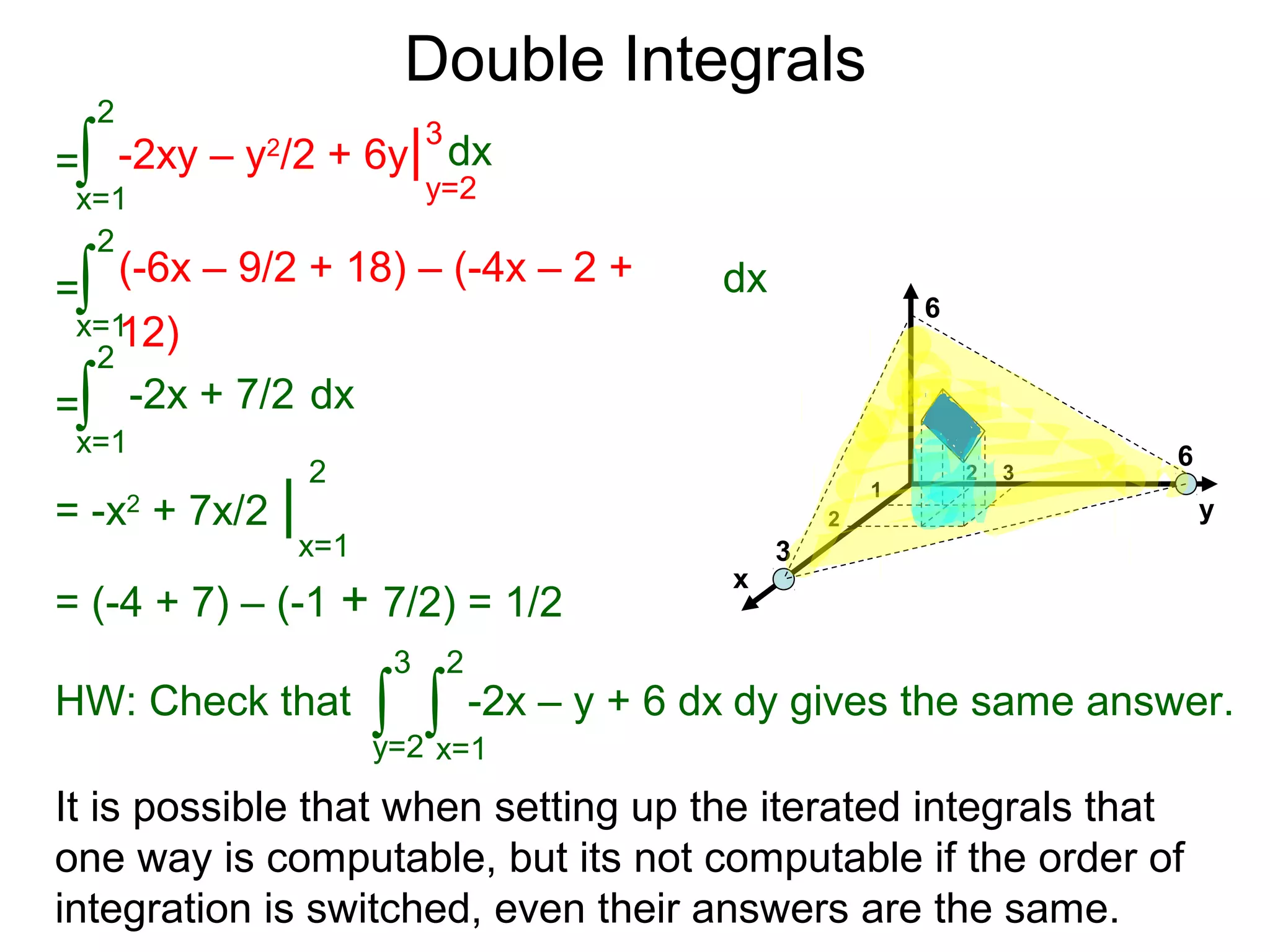

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

Example: Fid the volume of z = f(x, y) = -2x – y + 6 over the

domain [1, 2] x [2, 3]

x

y

6

6

3

1

2

2 3

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.

[

x=a

b

dy

y=c

d

f(x, y) dx ]∫∫V = f(x, y) dA =∫∫D

= [

x=a

b

dx

y=c

d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-33-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

Example: Fid the volume of z = f(x, y) = -2x – y + 6 over the

domain [1, 2] x [2, 3]

x

y

6

6

3

1

2

2 3

The volume is

x=1

2

dx

y=2

3

-2x – y + 6 dy∫ ∫

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.

[

x=a

b

dy

y=c

d

f(x, y) dx ]∫∫V = f(x, y) dA =∫∫D

= [

x=a

b

dx

y=c

d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-34-2048.jpg)

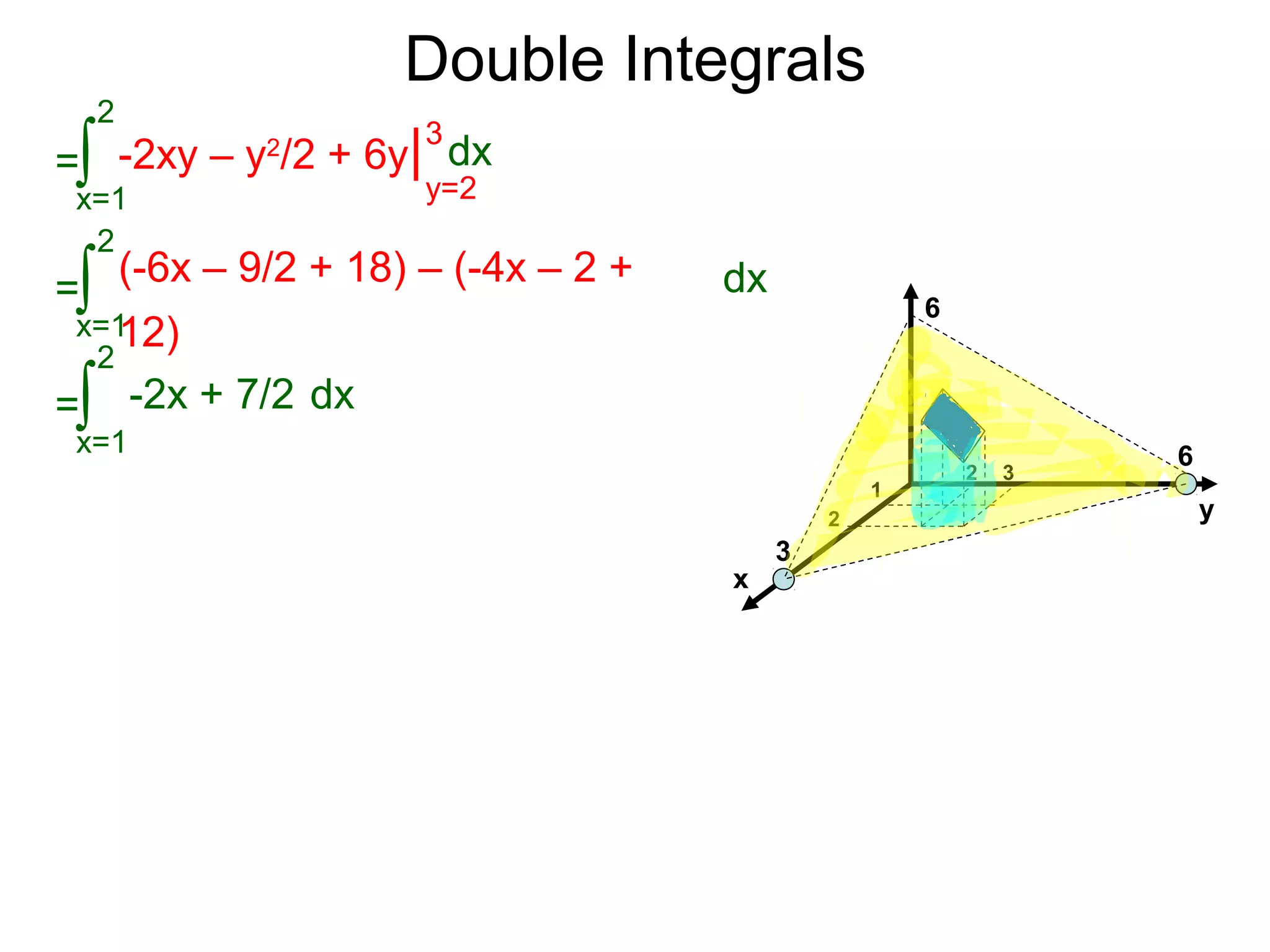

![Double Integrals

Theorem: Given z = f(x, y) > 0 a continuous function over the

domnain [a, b] x [c. d], then the following are equal:

Example: Fid the volume of z = f(x, y) = -2x – y + 6 over the

domain [1, 2] x [2, 3]

x

y

6

6

3

1

2

2 3

The volume is

x=1

2

dx

y=2

3

-2x – y + 6 dy∫ ∫

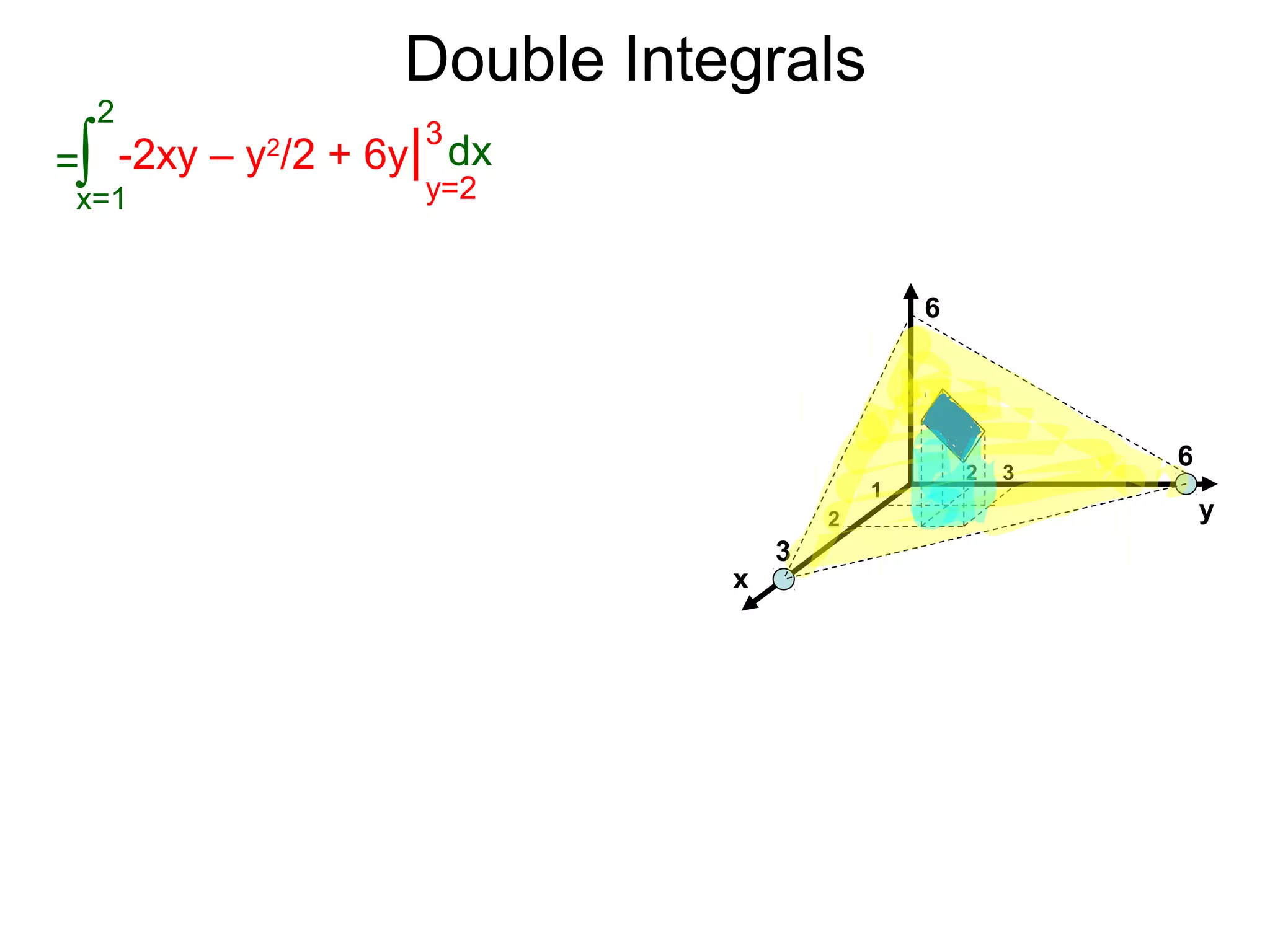

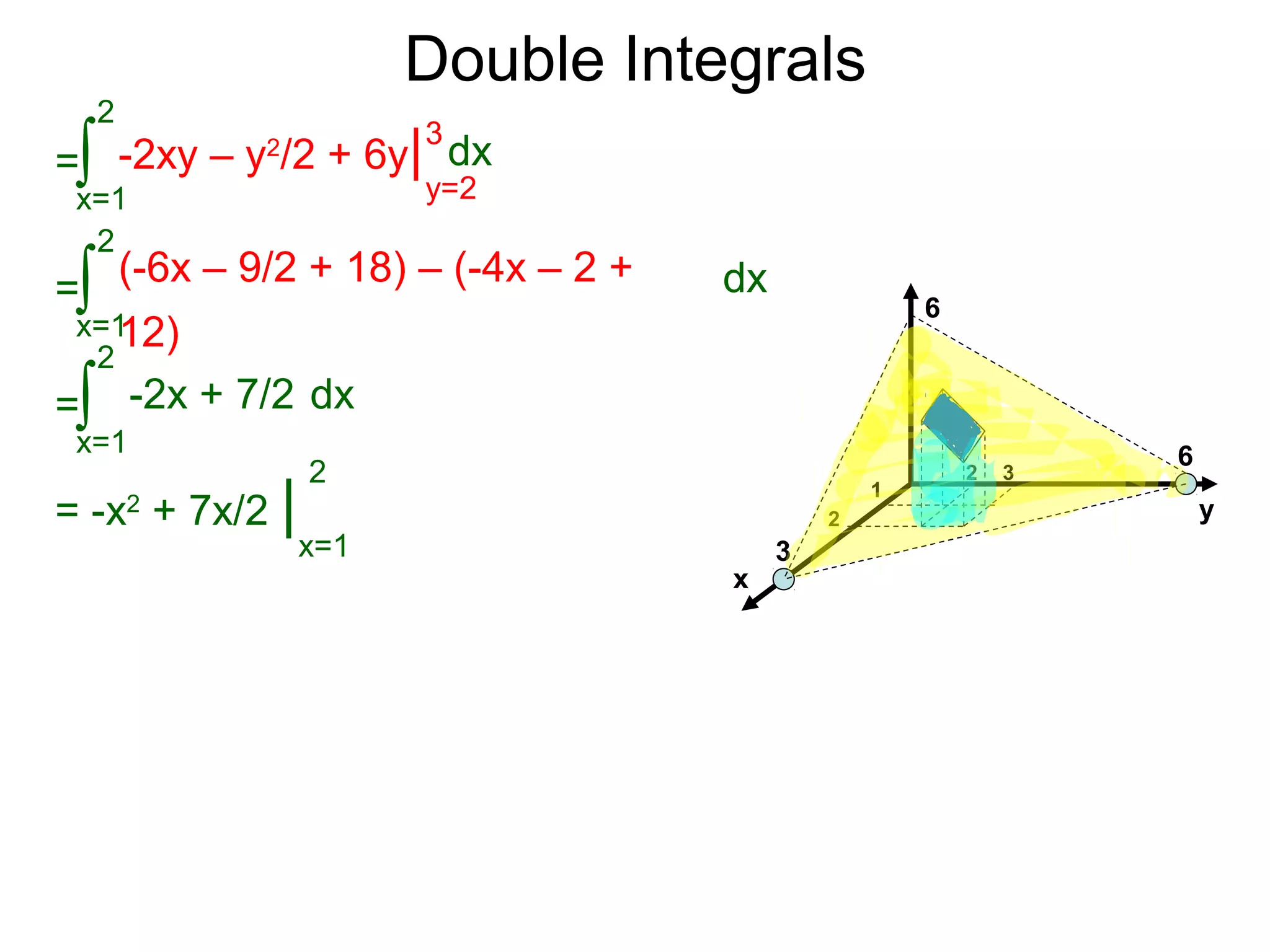

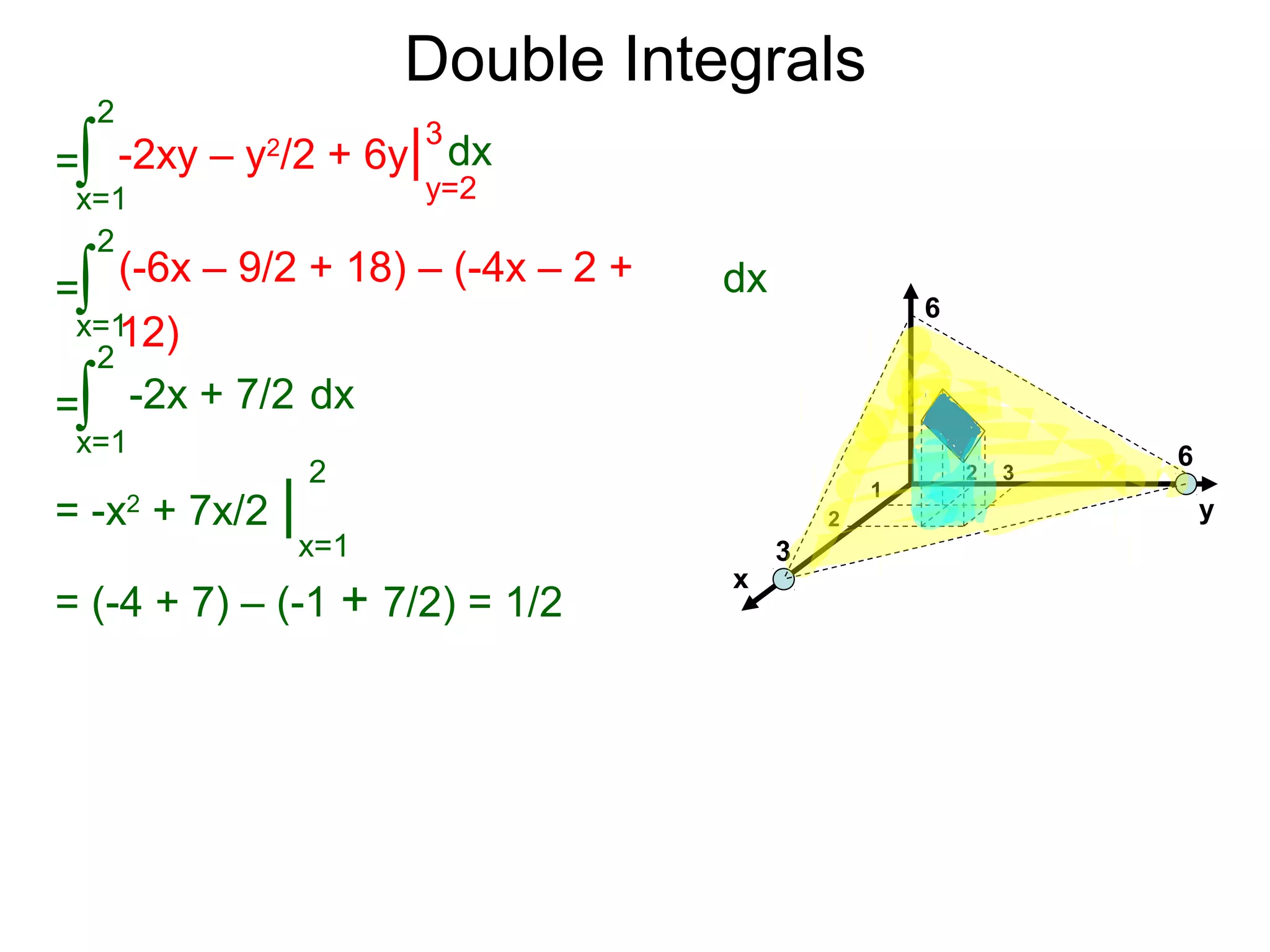

=

x=1

2

∫ -2xy – y2

/2 + 6y| dx

y=2

3

f(x, y) dx dyThe integral dx andf(x, y) dy ∫∫∫∫ are

called iterated integrals meaning the integral is done one

step at a time.

[

x=a

b

dy

y=c

d

f(x, y) dx ]∫∫V = f(x, y) dA =∫∫D

= [

x=a

b

dx

y=c

d

f(x, y) dy ]∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-35-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-43-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Since ex+2y

is continuous, we may change the integral to

an iterated integral, say

0

1

dy

1

ex+2y

dx∫ ∫x=0

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-44-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Since ex+2y

is continuous, we may change the integral to

an iterated integral, say

0

1

dy

1

ex+2y

dx∫ ∫x=0

=

0

1 1

ex+2y

| dy∫ x=0

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-45-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Since ex+2y

is continuous, we may change the integral to

an iterated integral, say

0

1

dy

1

ex+2y

dx∫ ∫x=0

=

0

1 1

ex+2y

| dy∫ x=0

=

0

1

e1+2y

– e2y

dy∫

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-46-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Since ex+2y

is continuous, we may change the integral to

an iterated integral, say

0

1

dy

1

ex+2y

dx∫ ∫x=0

=

0

1 1

ex+2y

| dy∫ x=0

=

0

1

e1+2y

– e2y

dy∫

= (e1+2y

– e2y

) |

1

y=0

1

2

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-47-2048.jpg)

![Double Integrals

Since ex+2y

is continuous, we may change the integral to

an iterated integral, say

0

1

dy

1

ex+2y

dx∫ ∫x=0

=

0

1 1

ex+2y

| dy∫ x=0

=

0

1

e1+2y

– e2y

dy∫

= (e1+2y

– e2y

) |

1

y=0

= [(e3

– e2

) – (e – 1)] =

e3

– e2

– e +1

2

1

2

1

2

Example: Find the where D = [0, 1] x [0, 1]

D

ex+2y

dA∫ ∫](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22doubleintegrals-130423213737-phpapp02/75/22-double-integrals-48-2048.jpg)