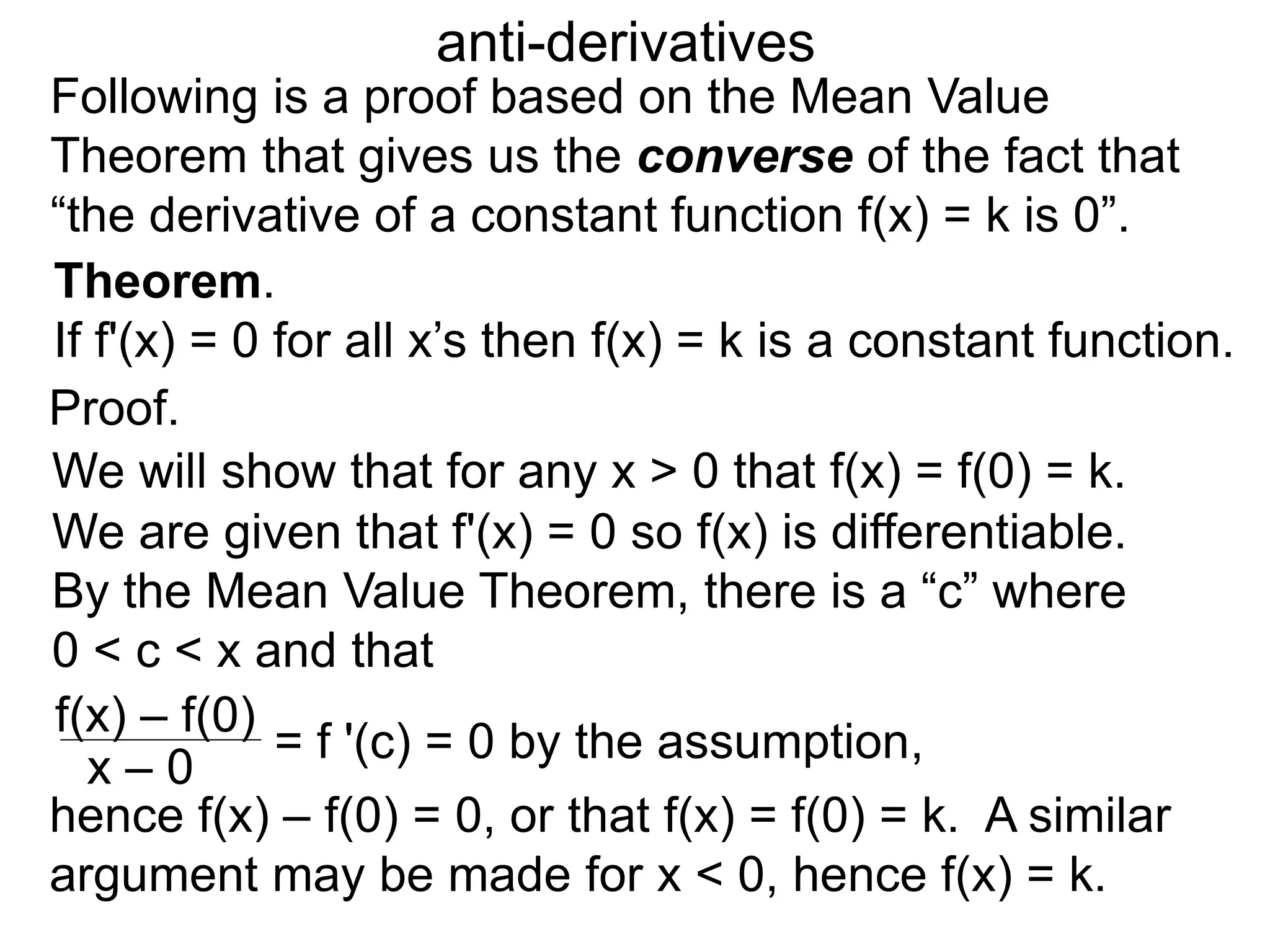

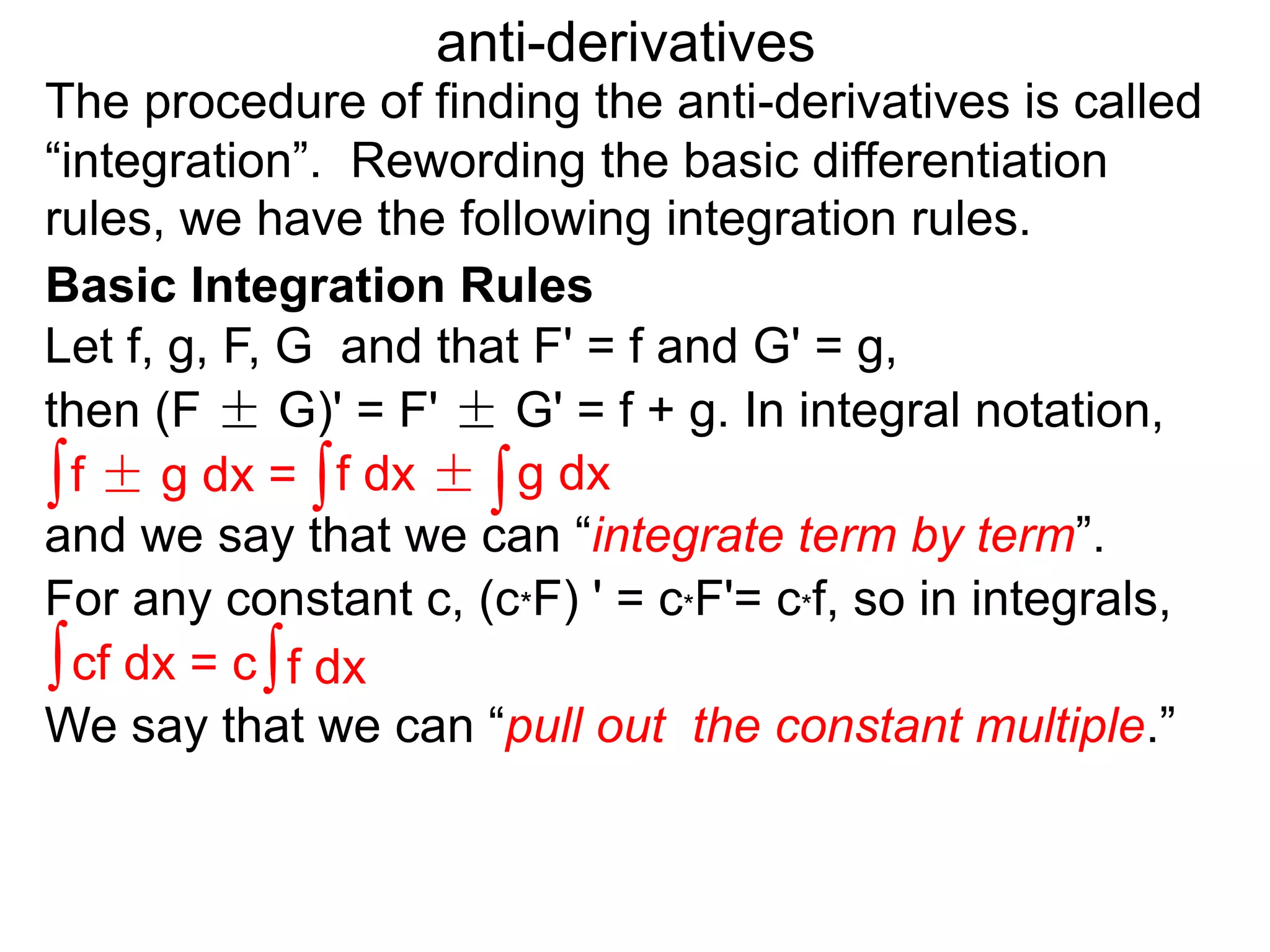

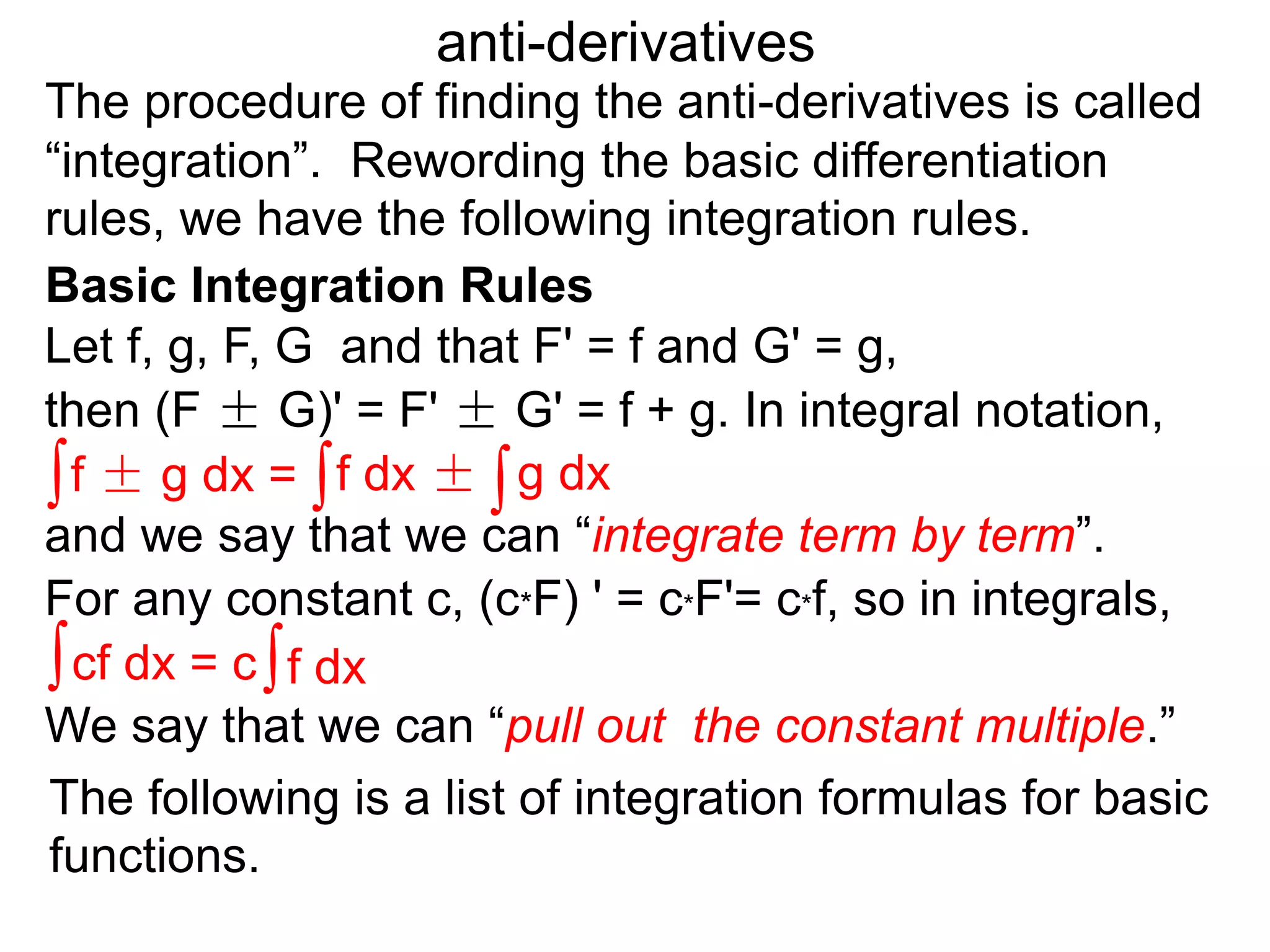

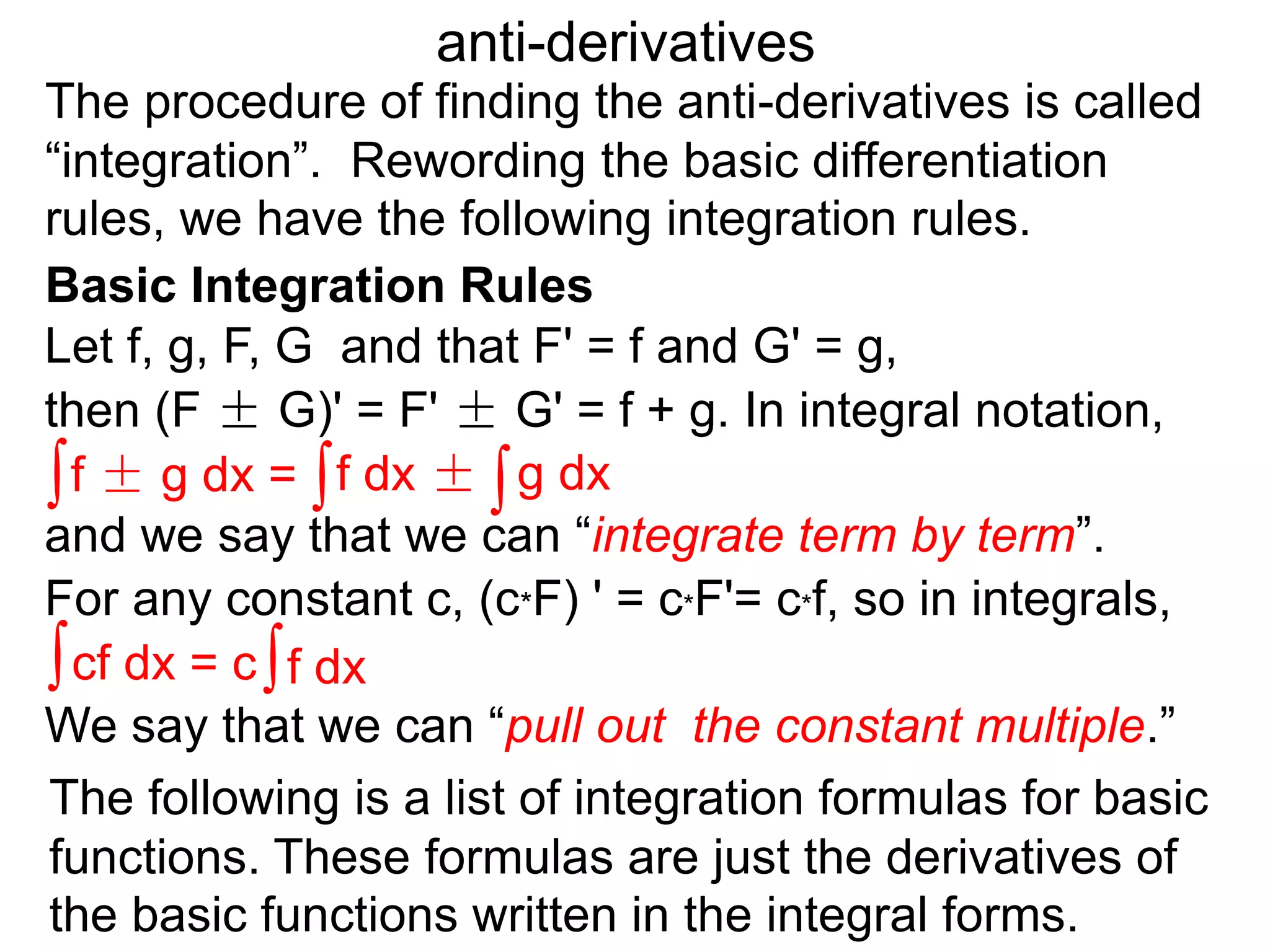

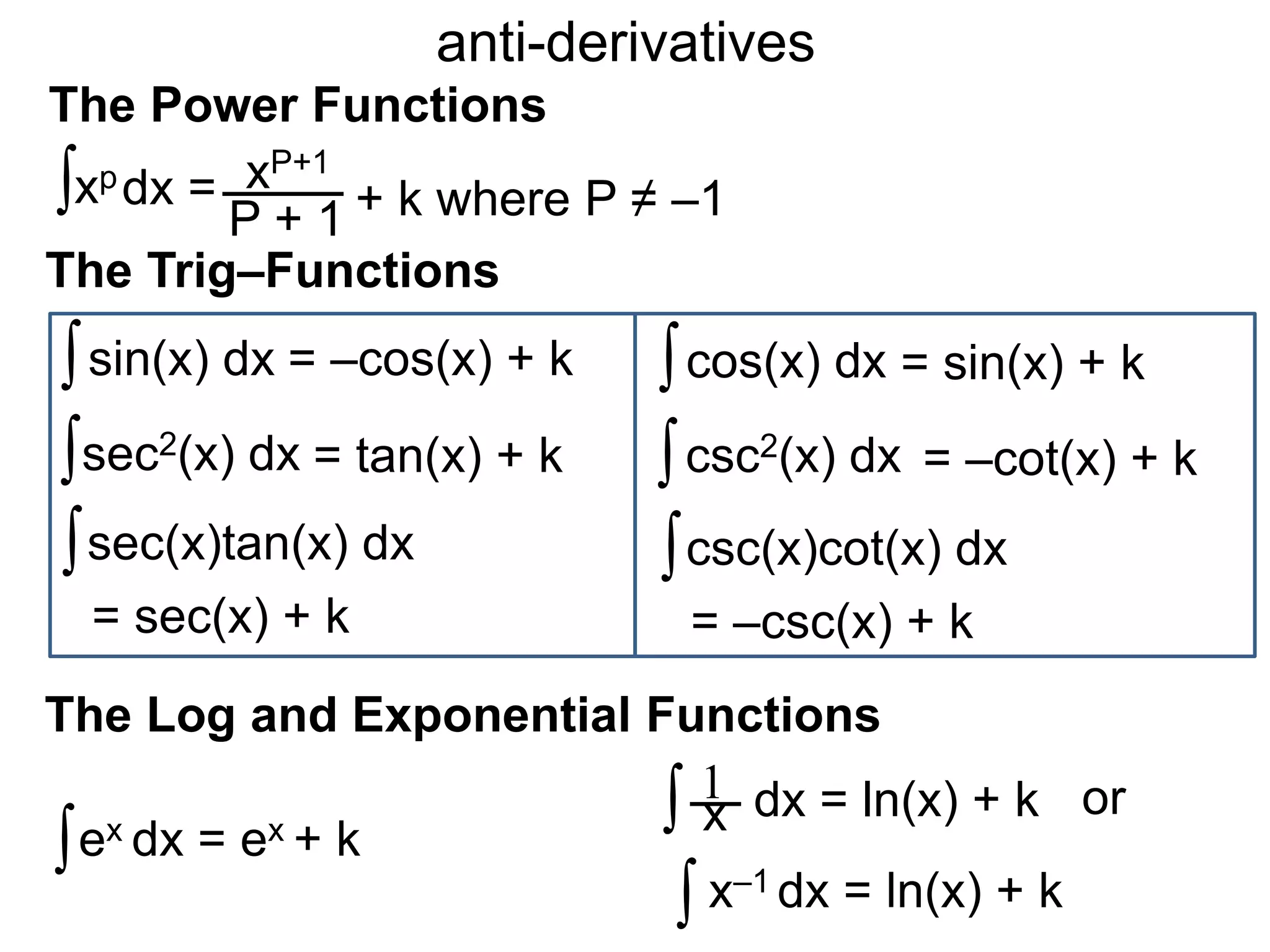

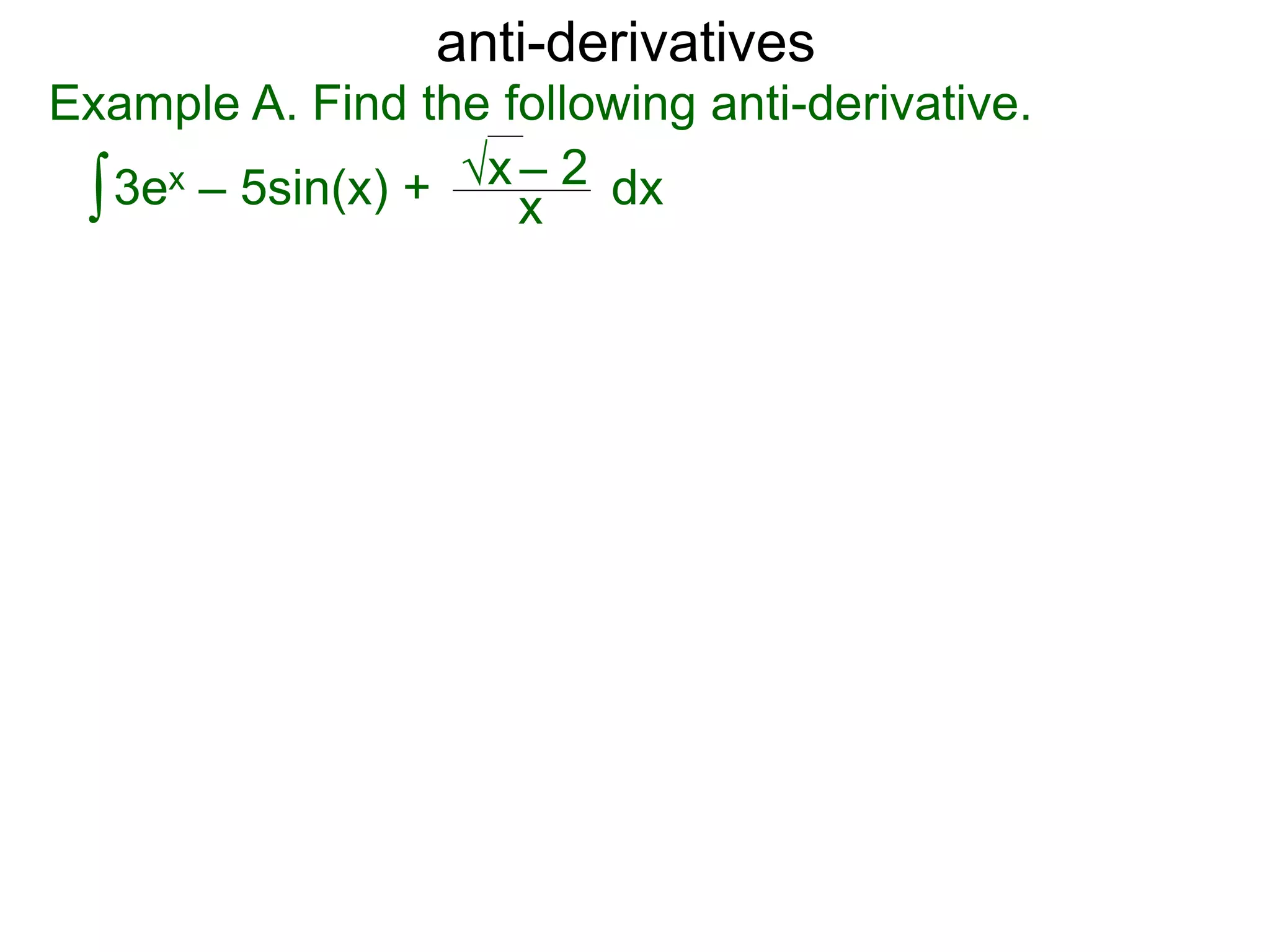

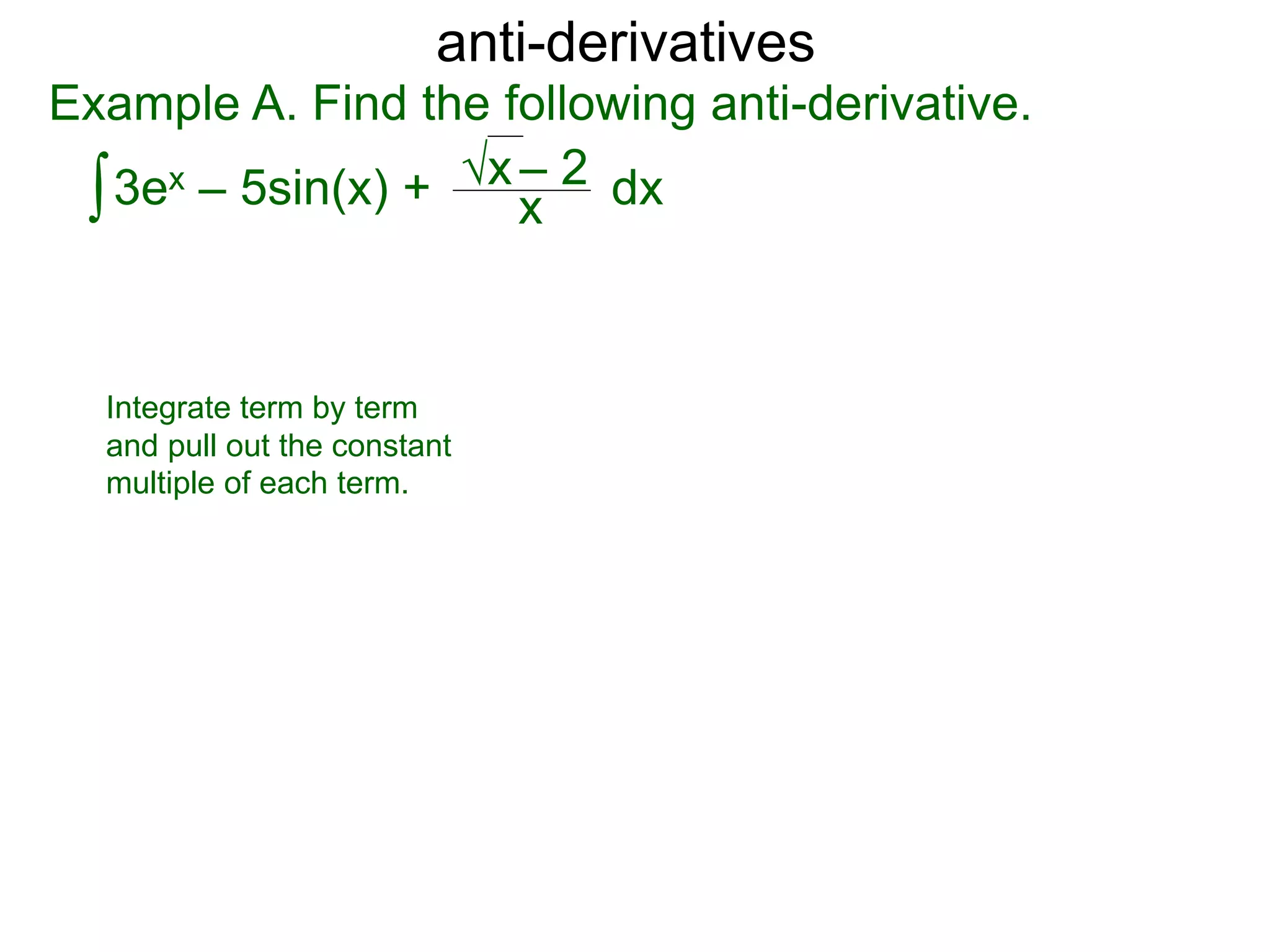

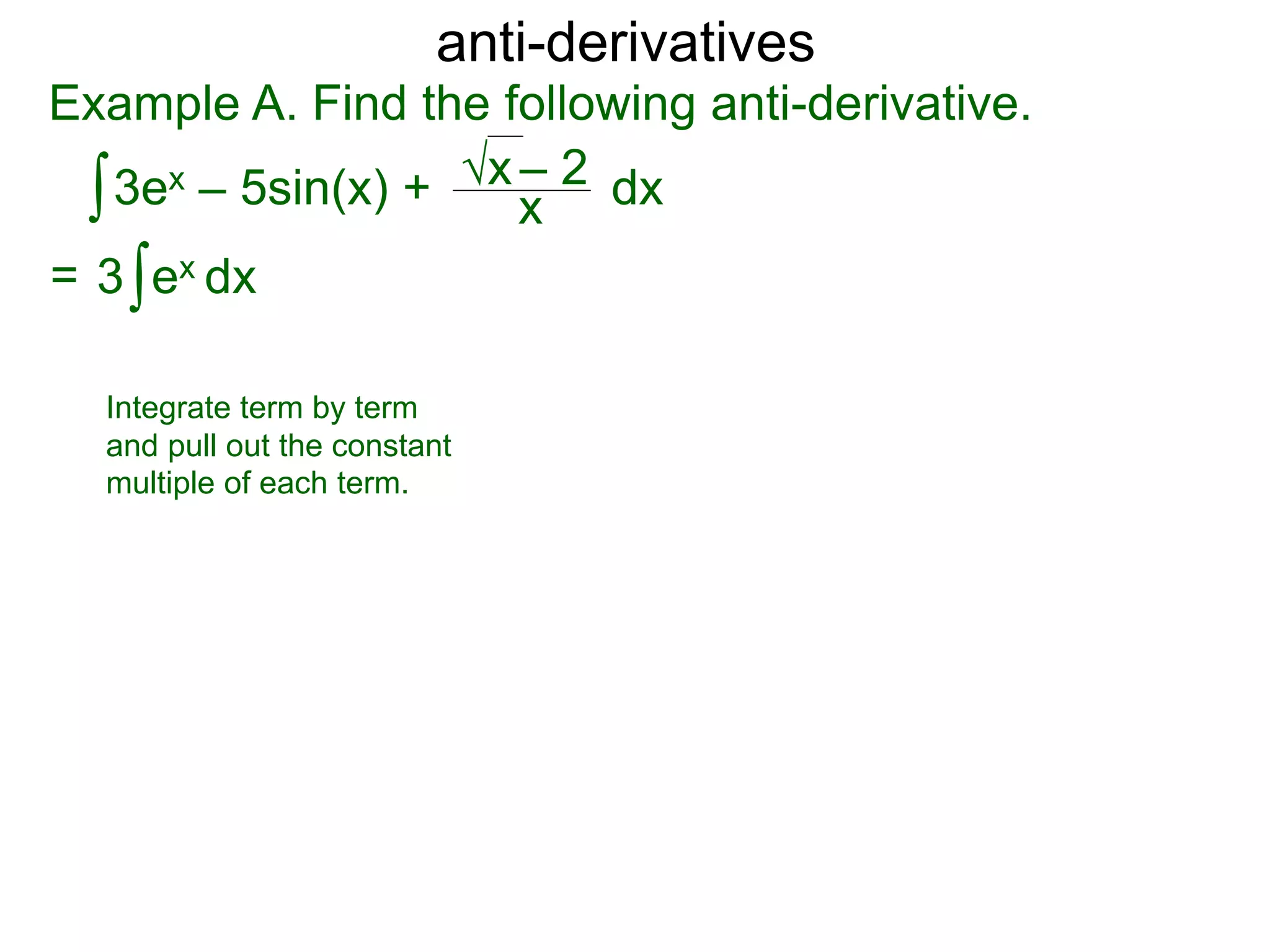

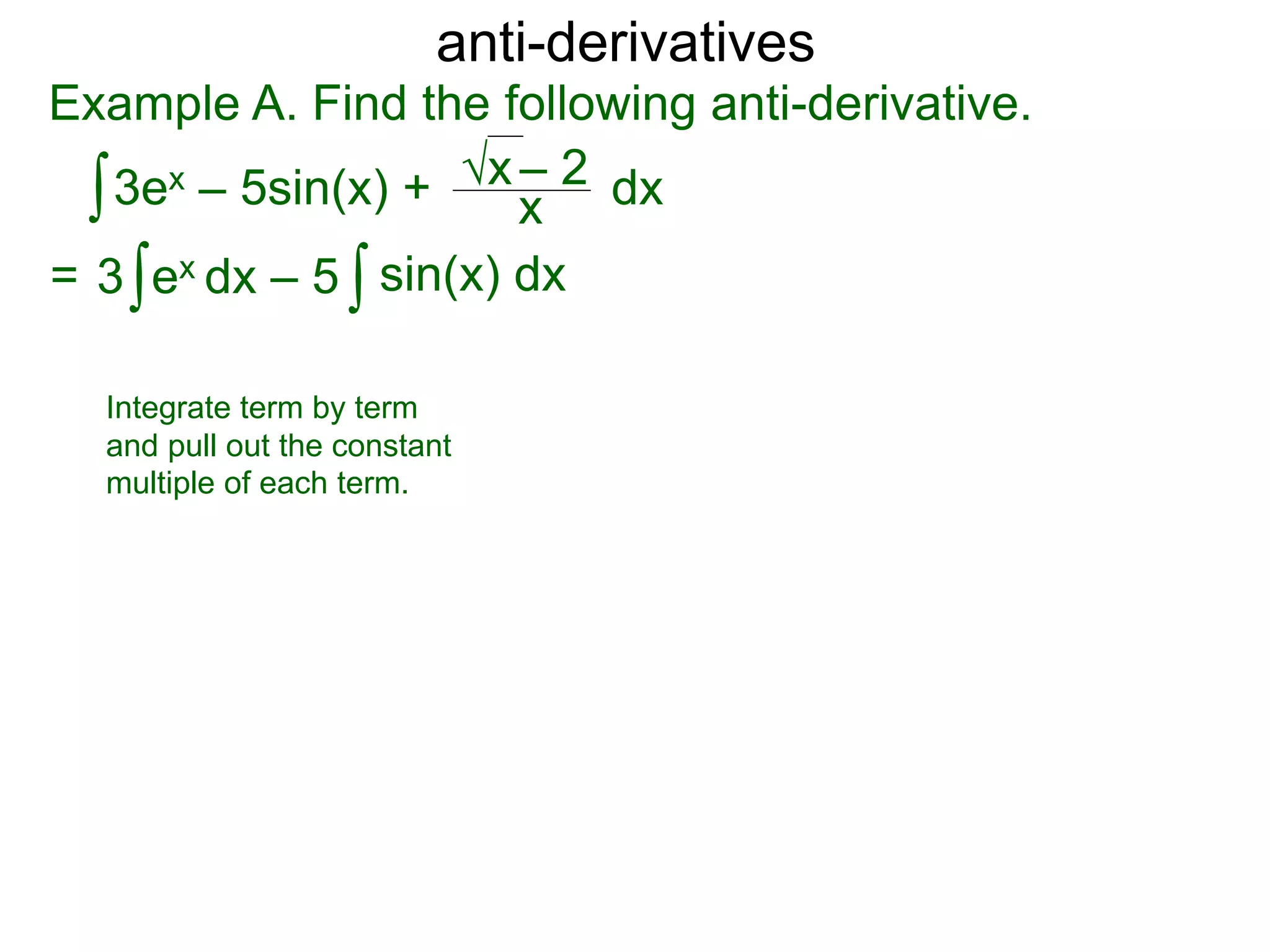

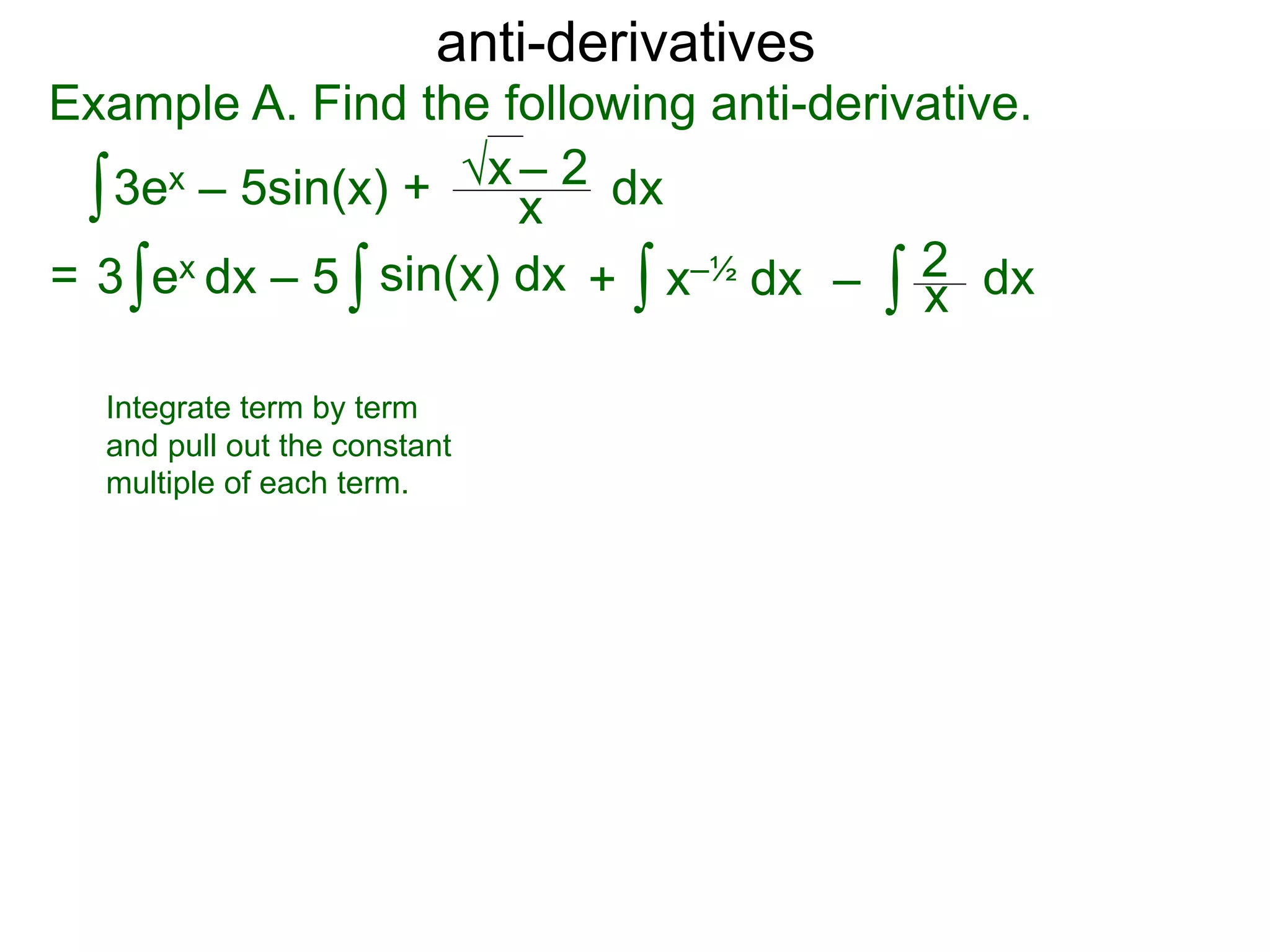

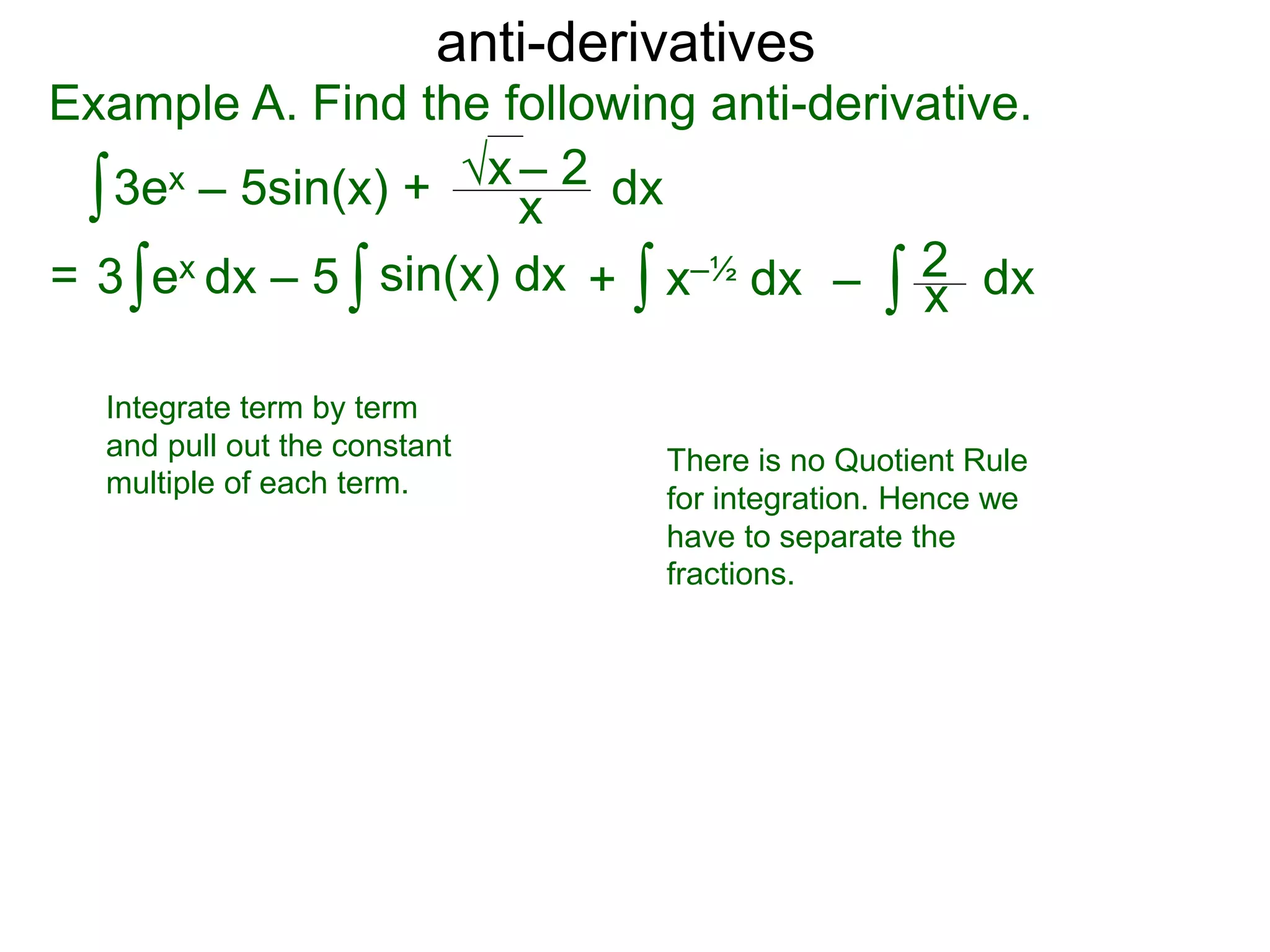

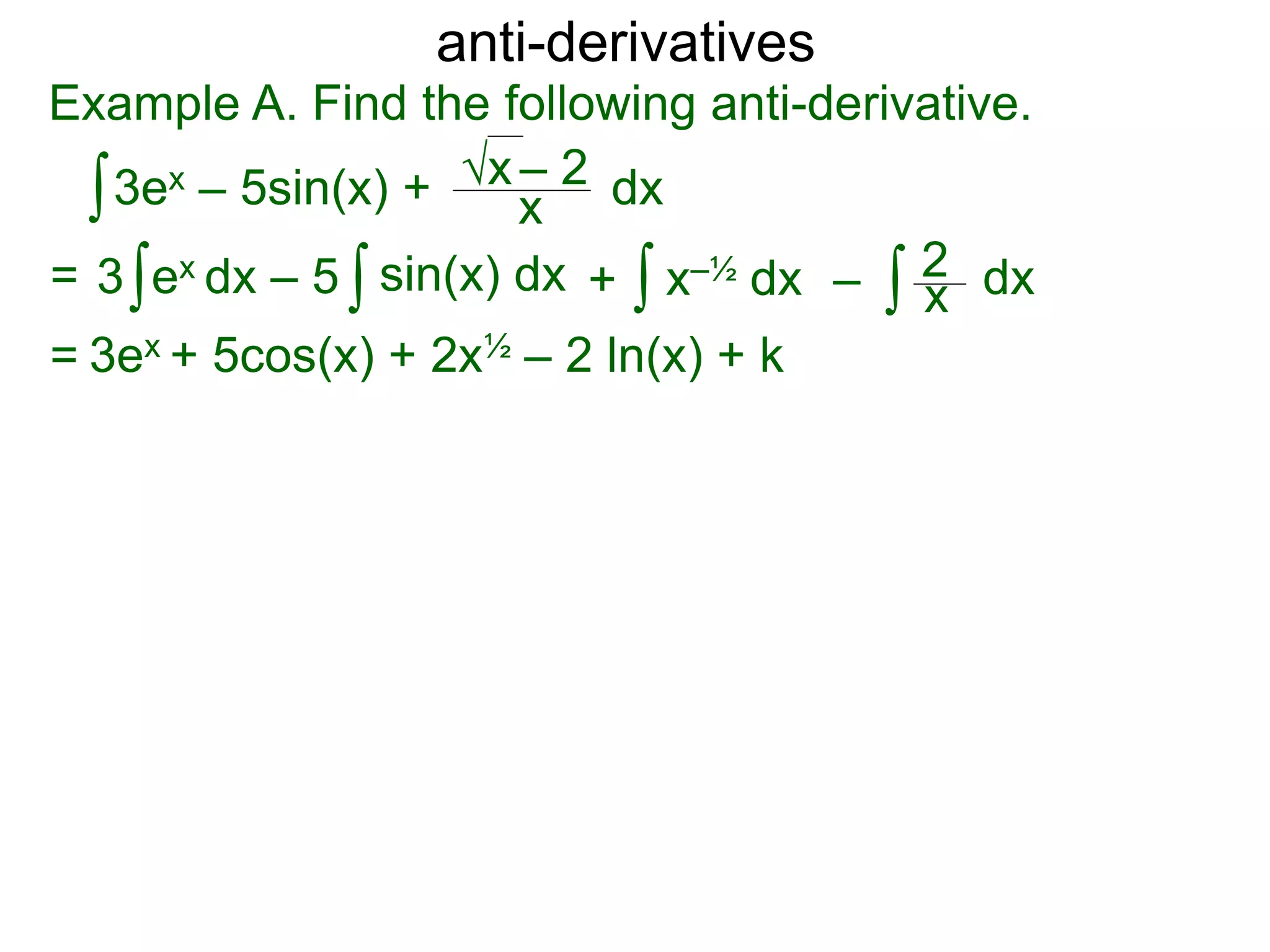

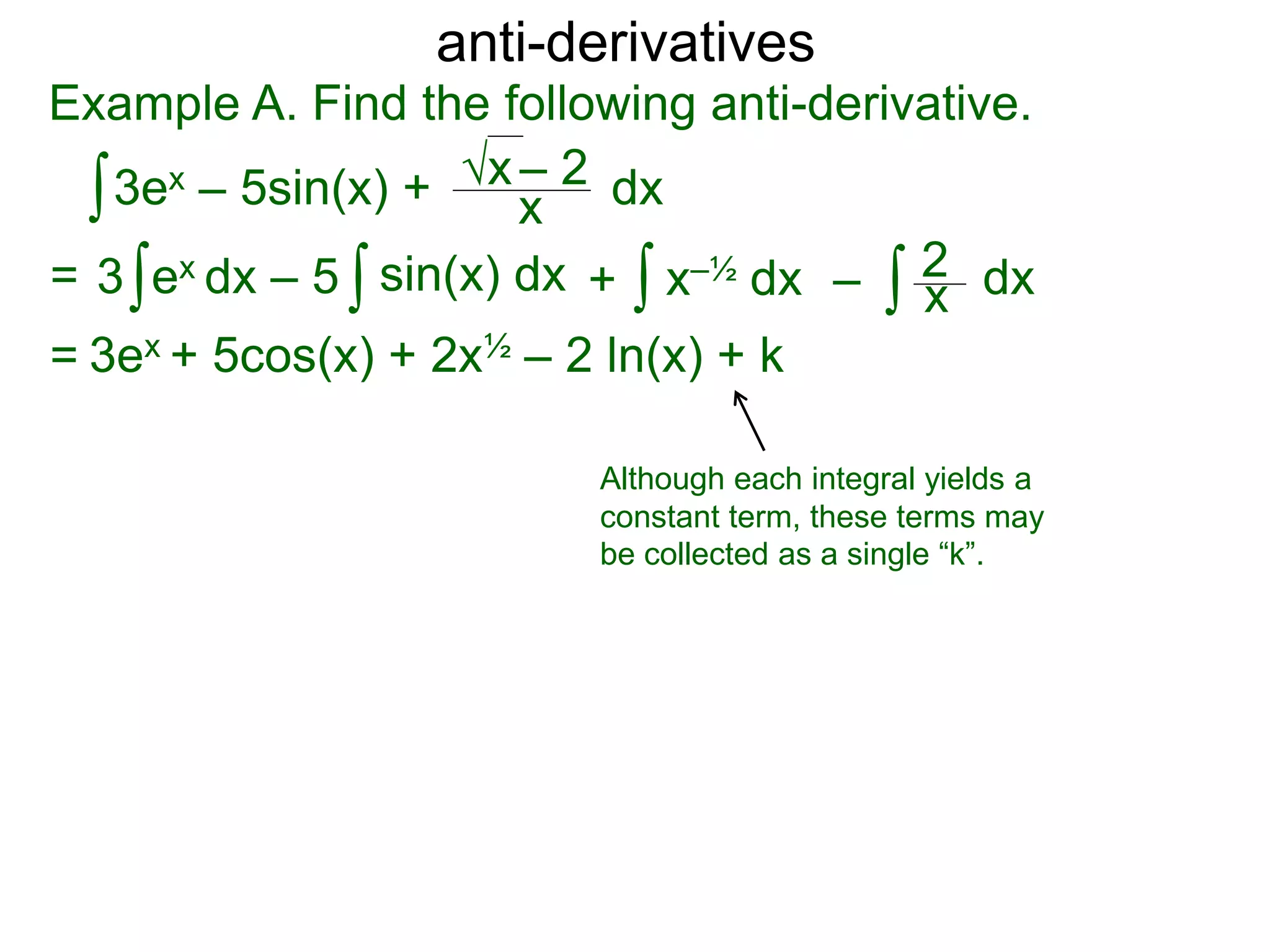

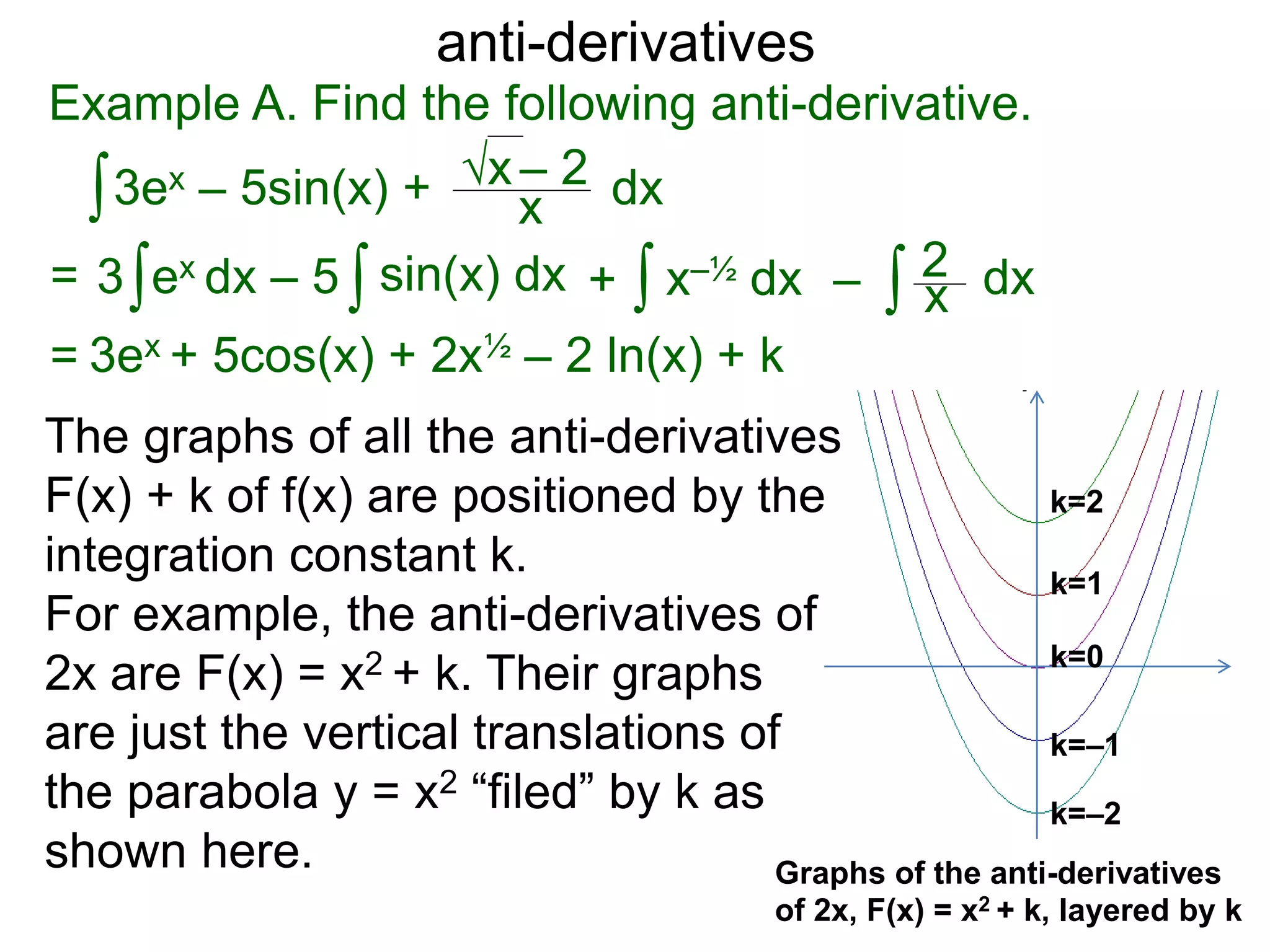

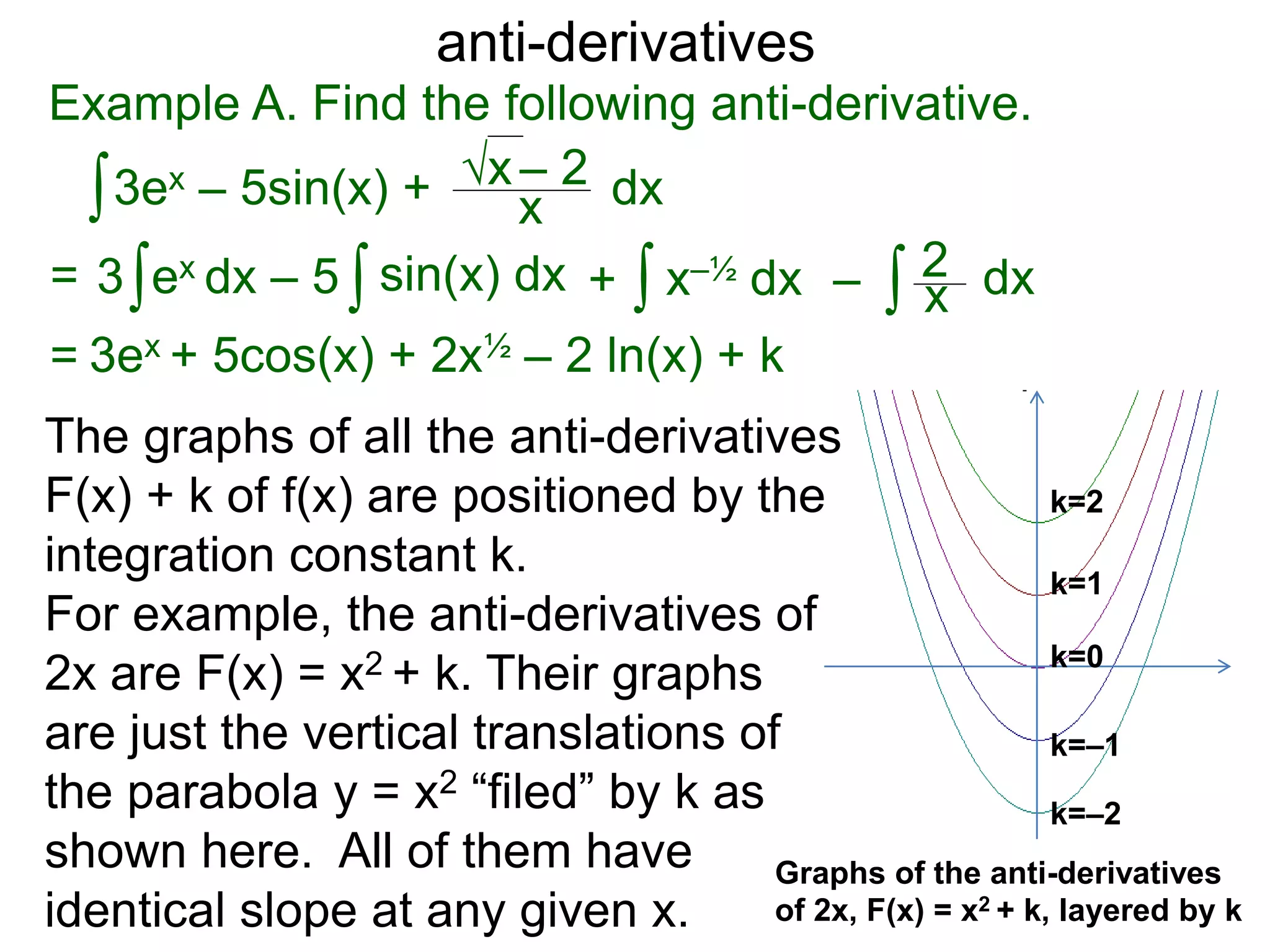

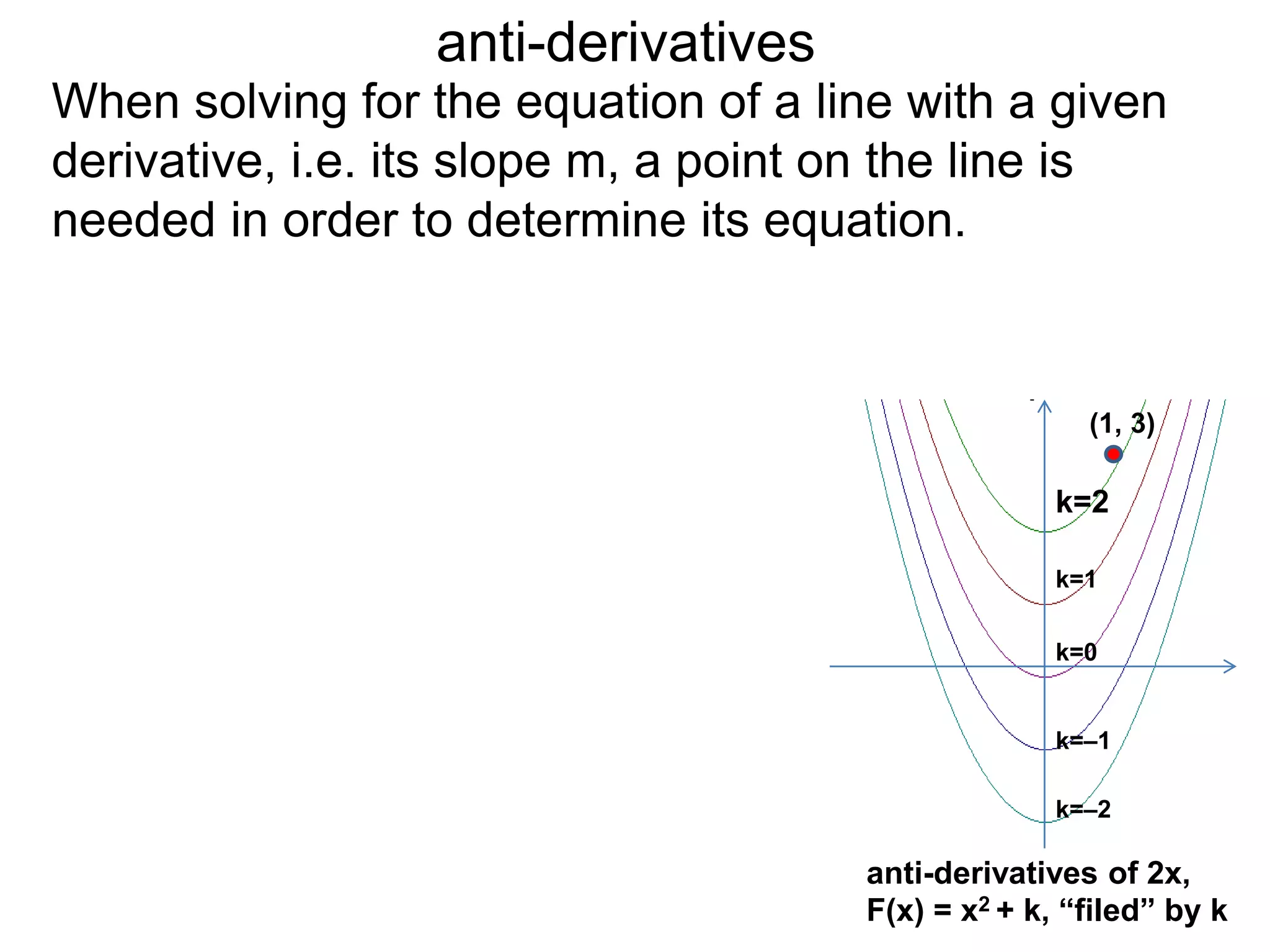

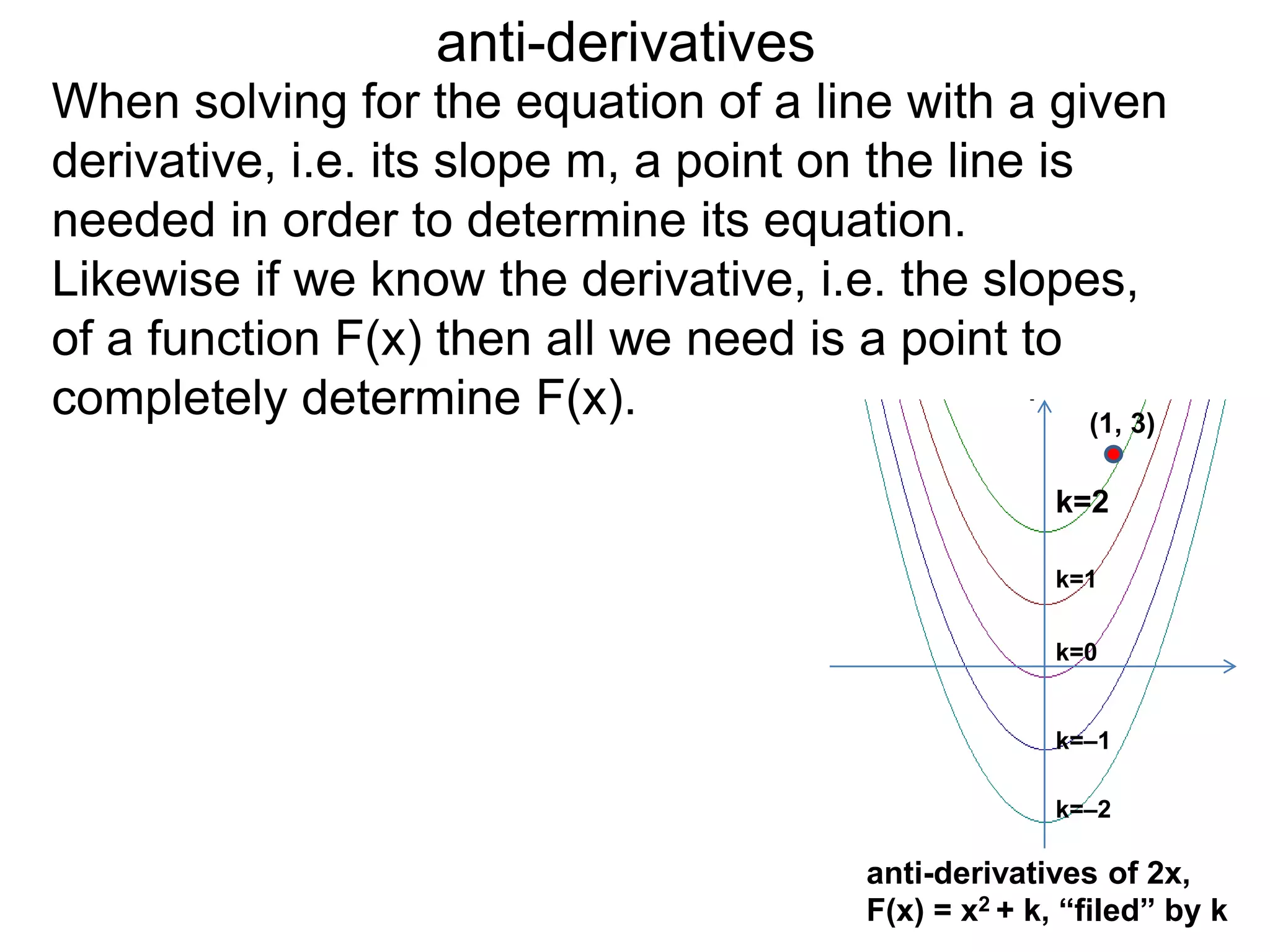

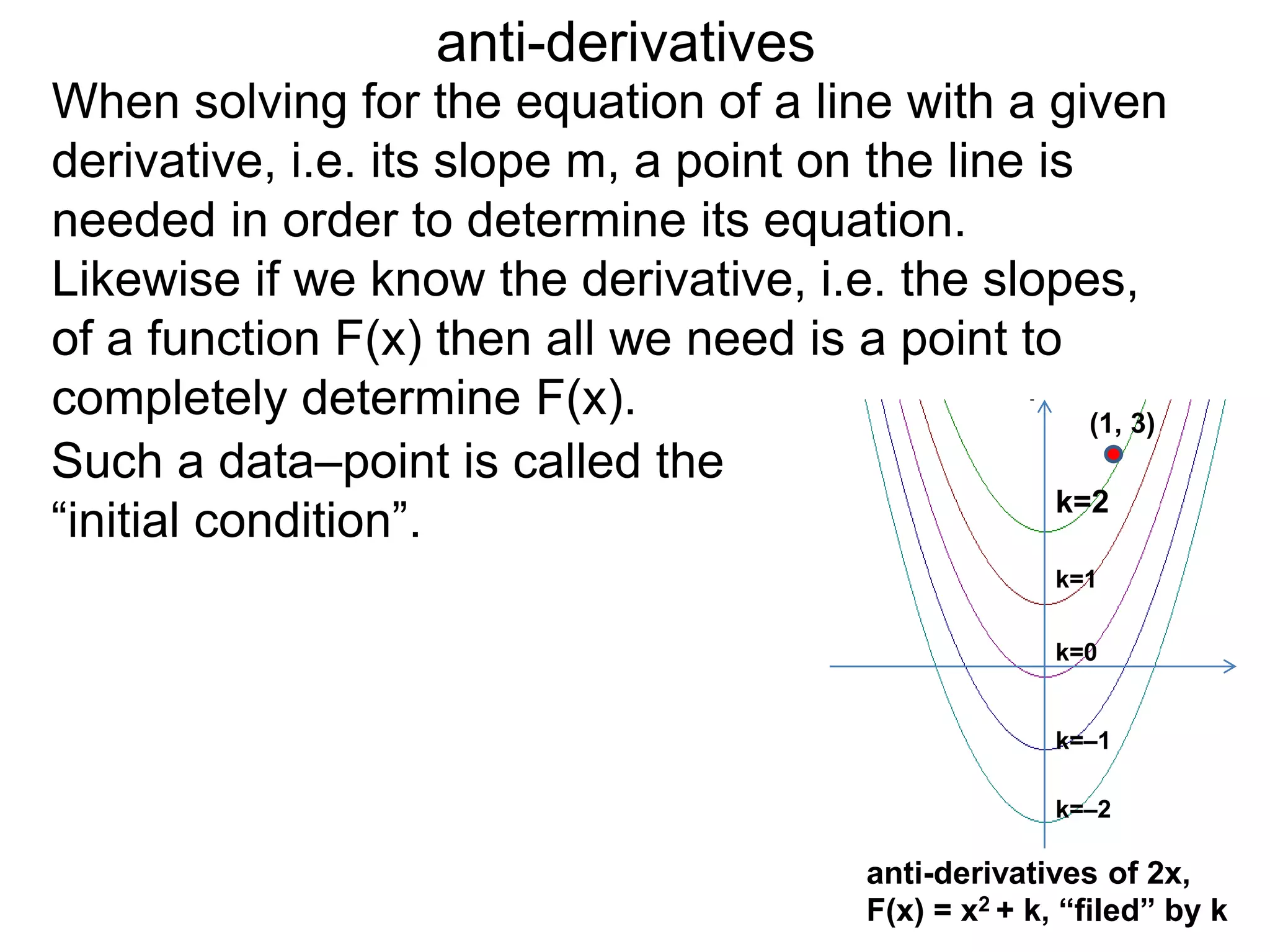

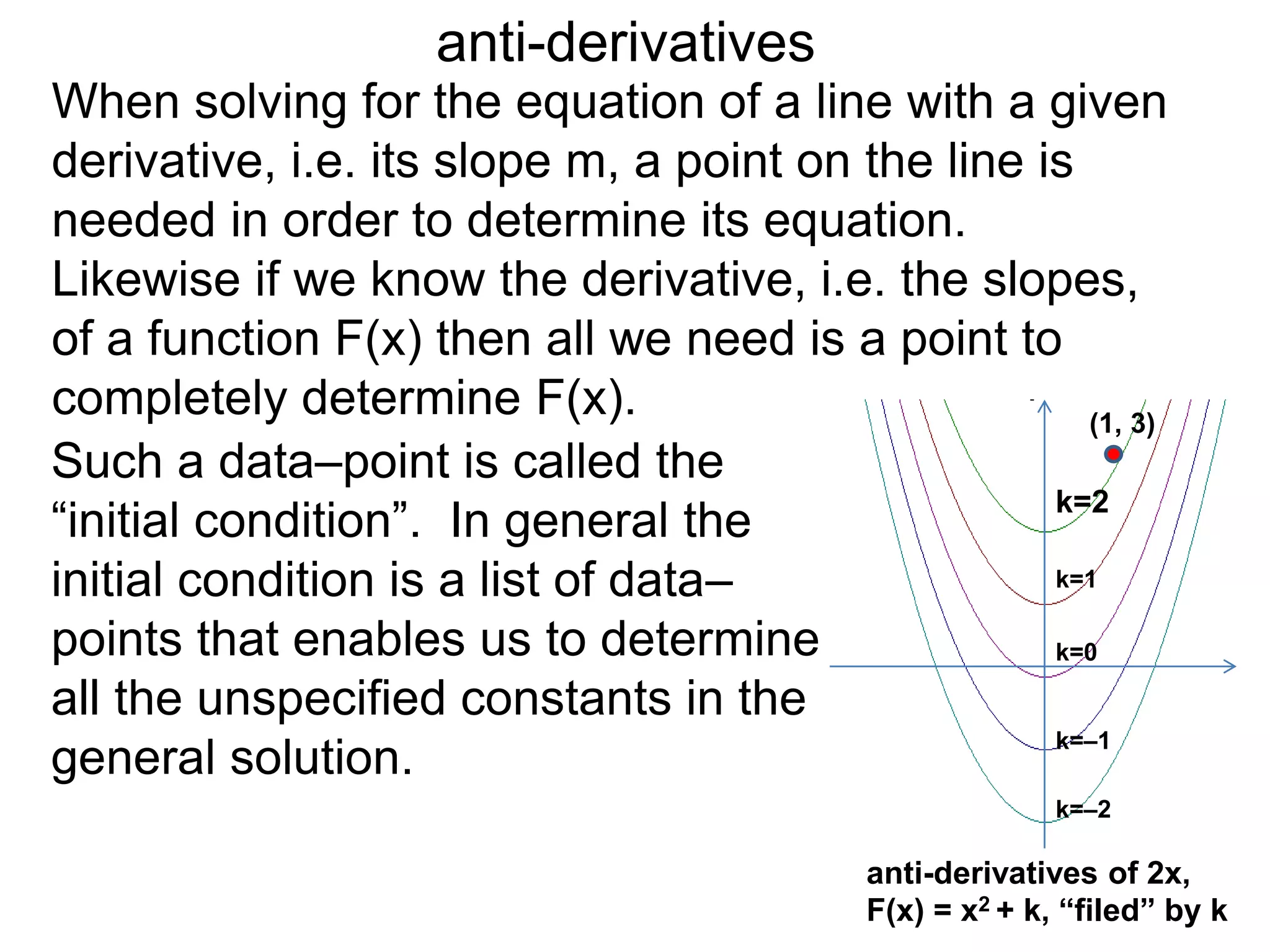

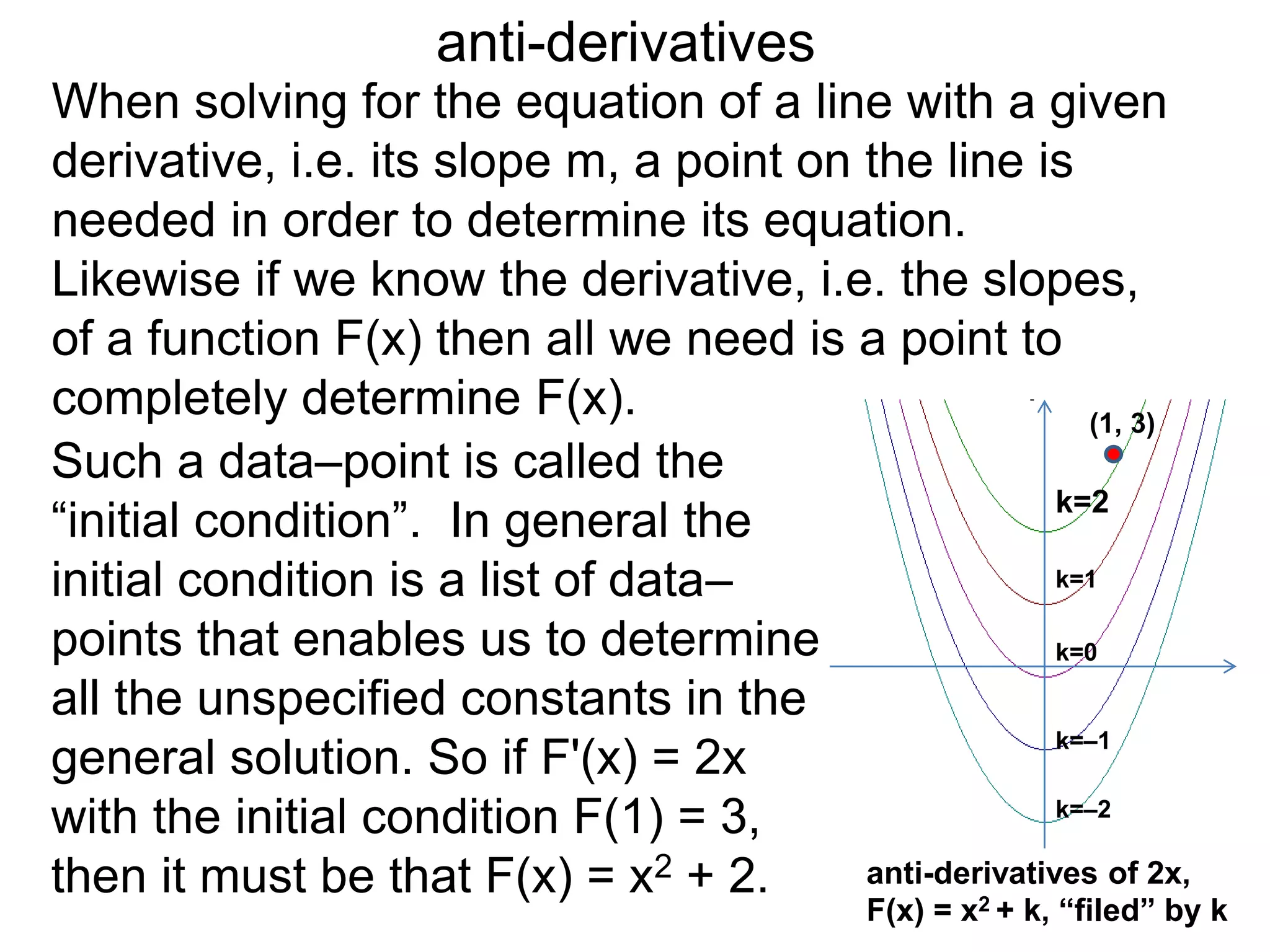

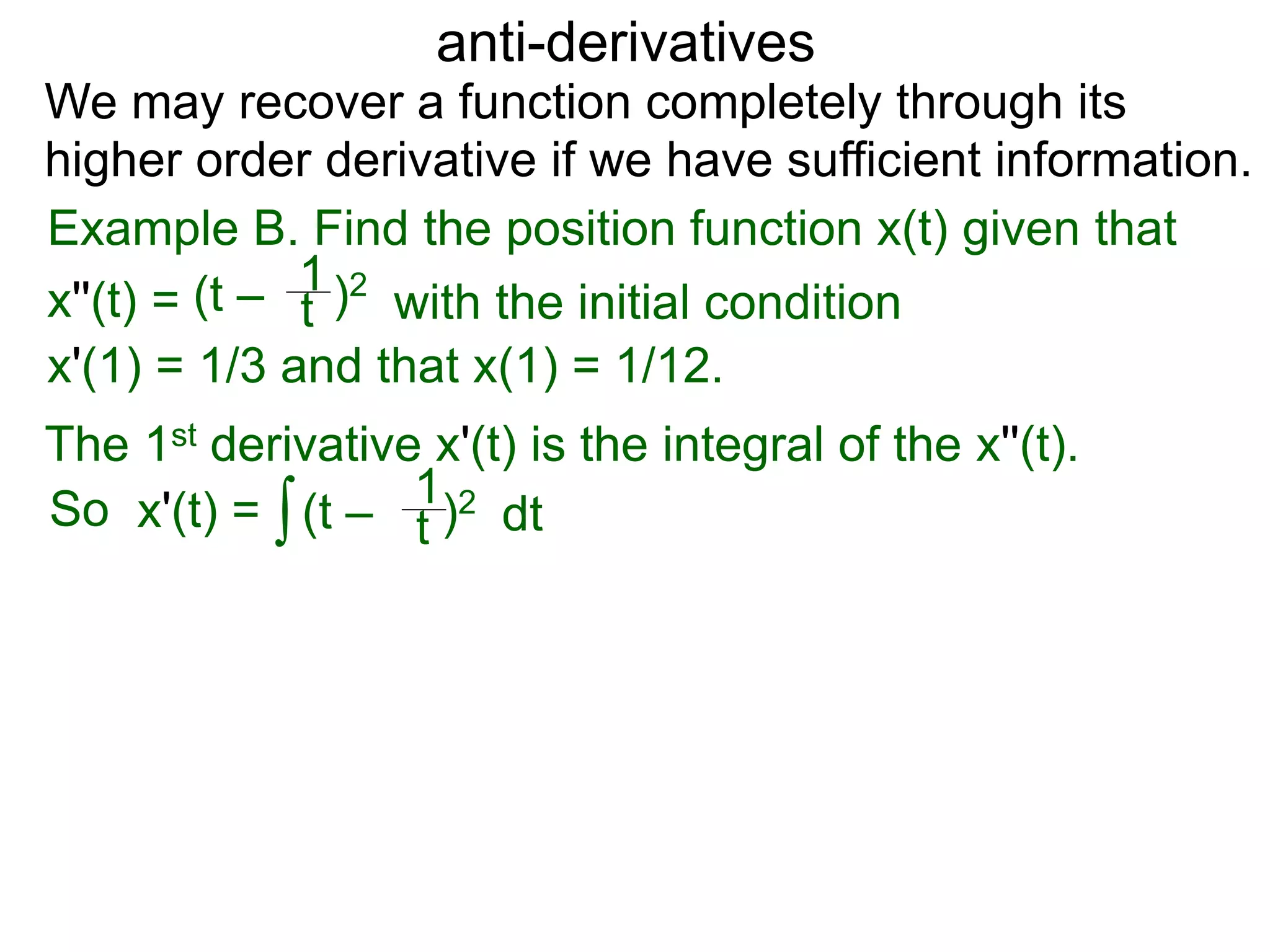

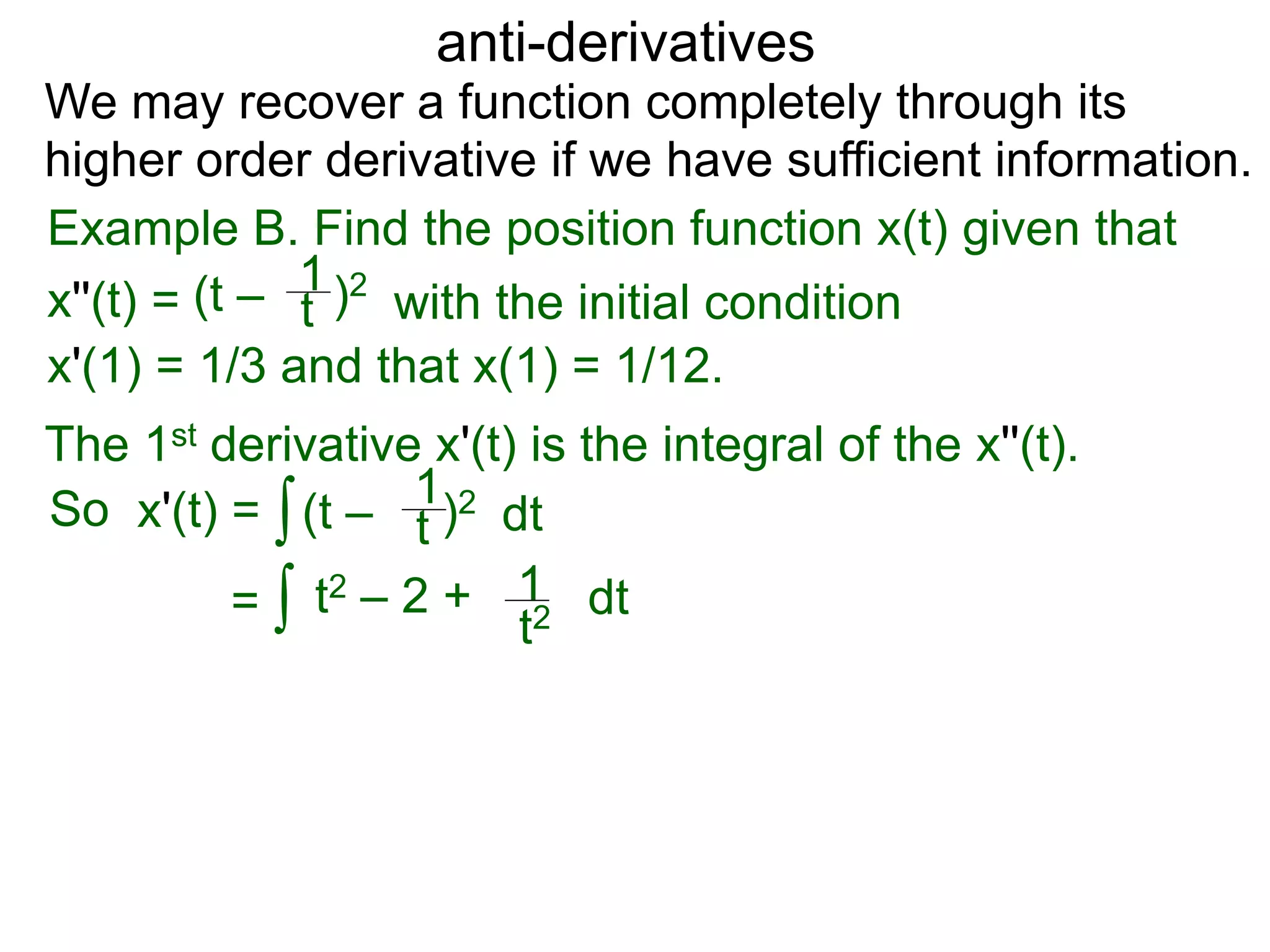

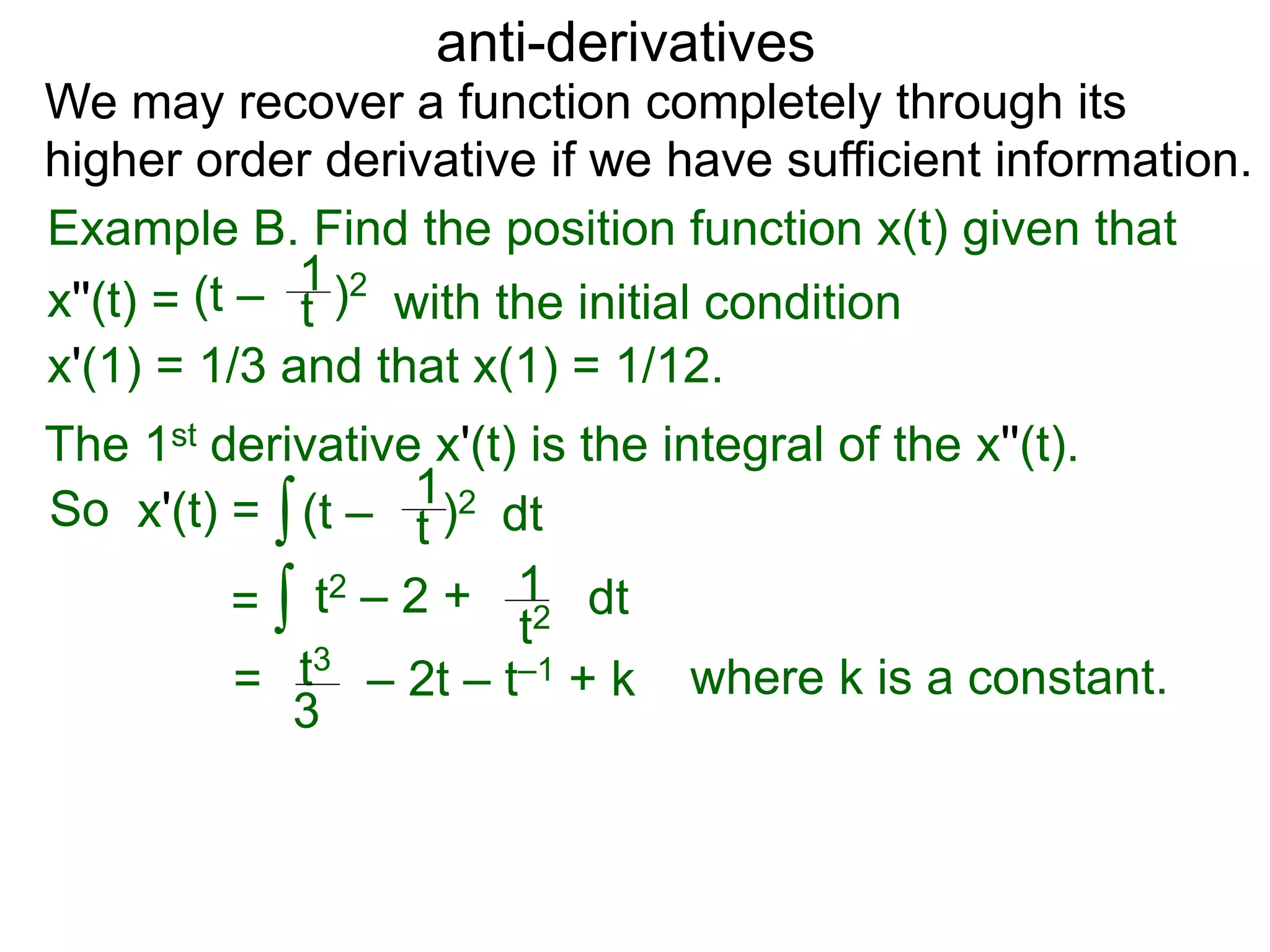

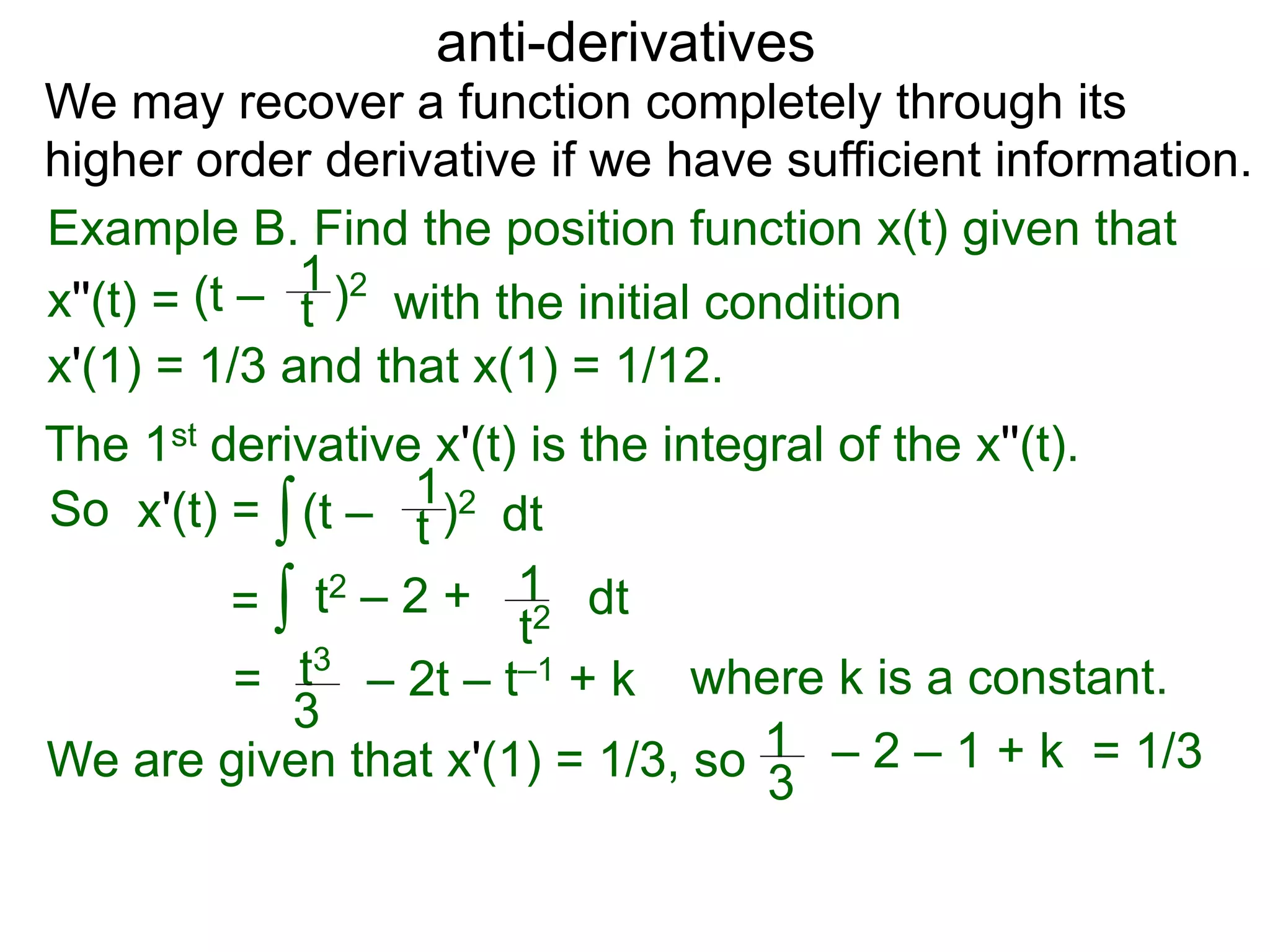

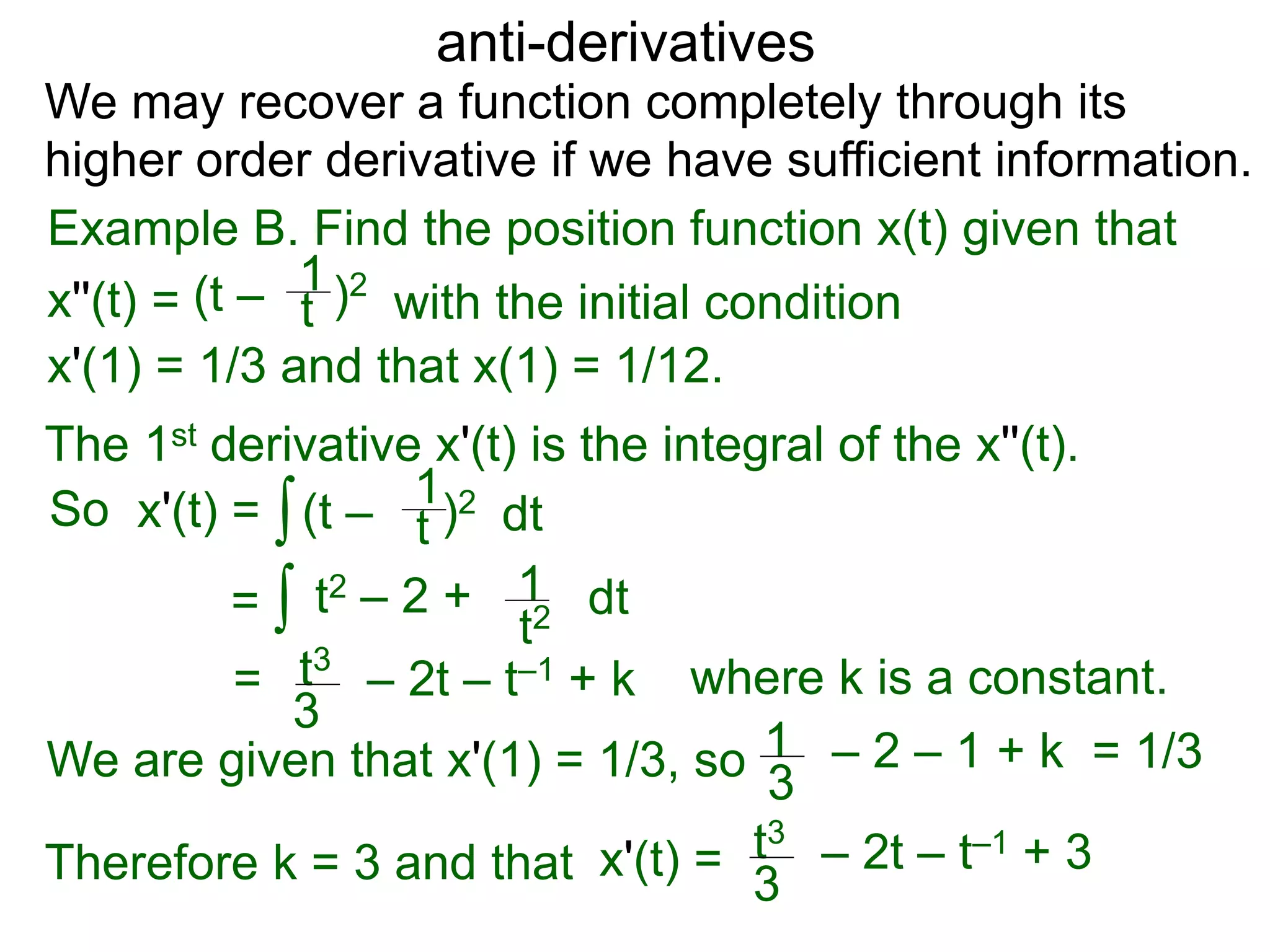

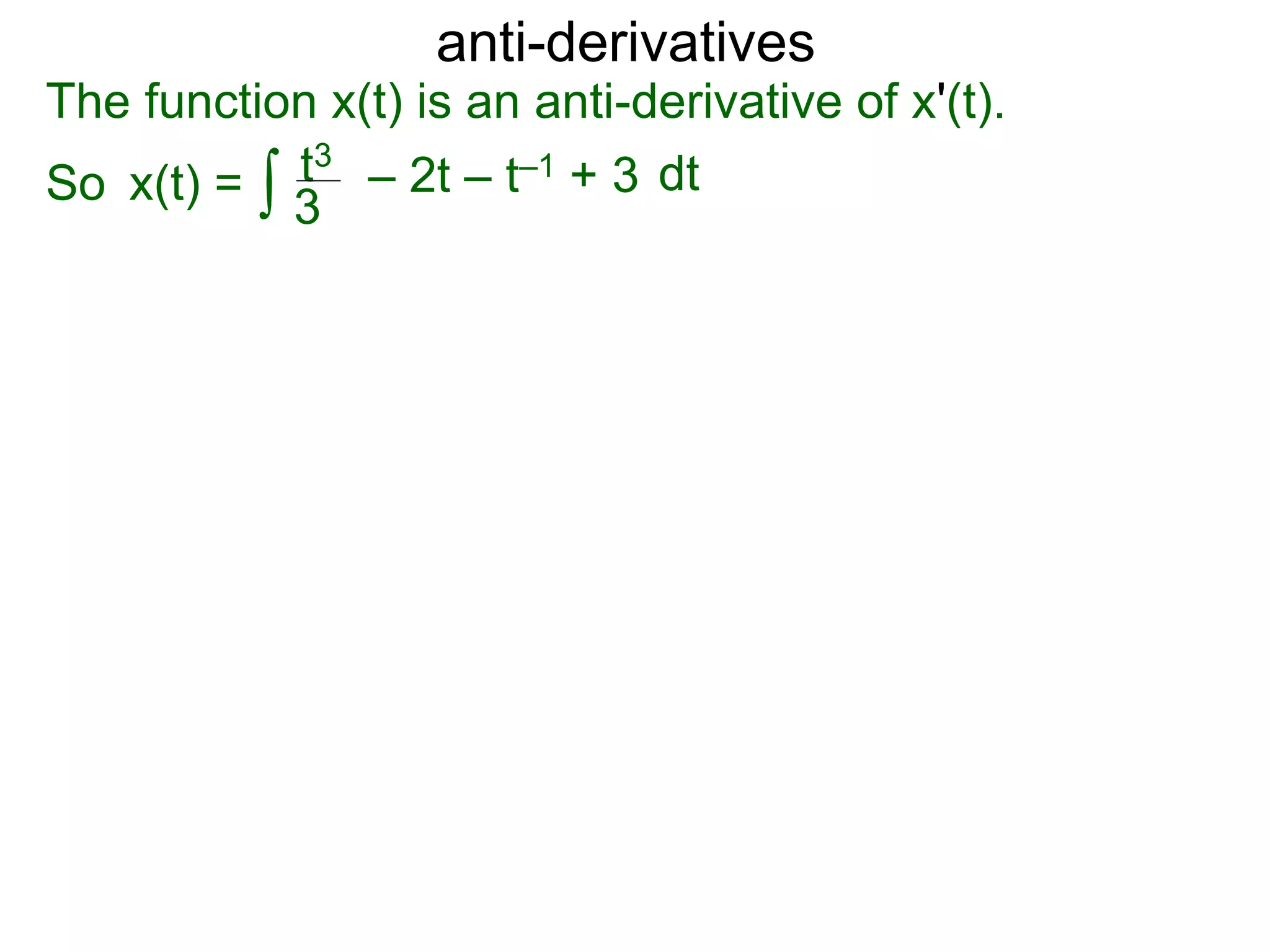

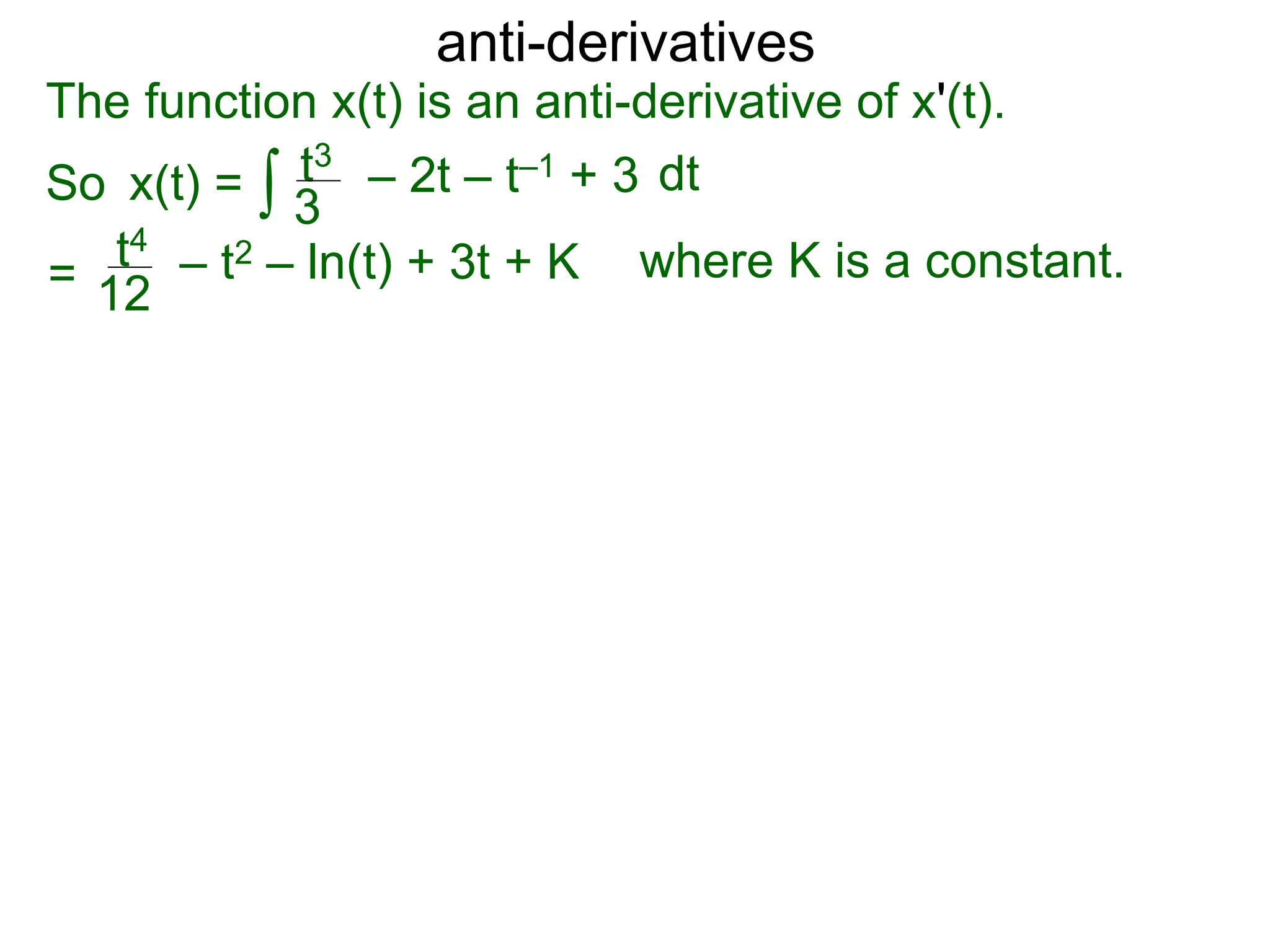

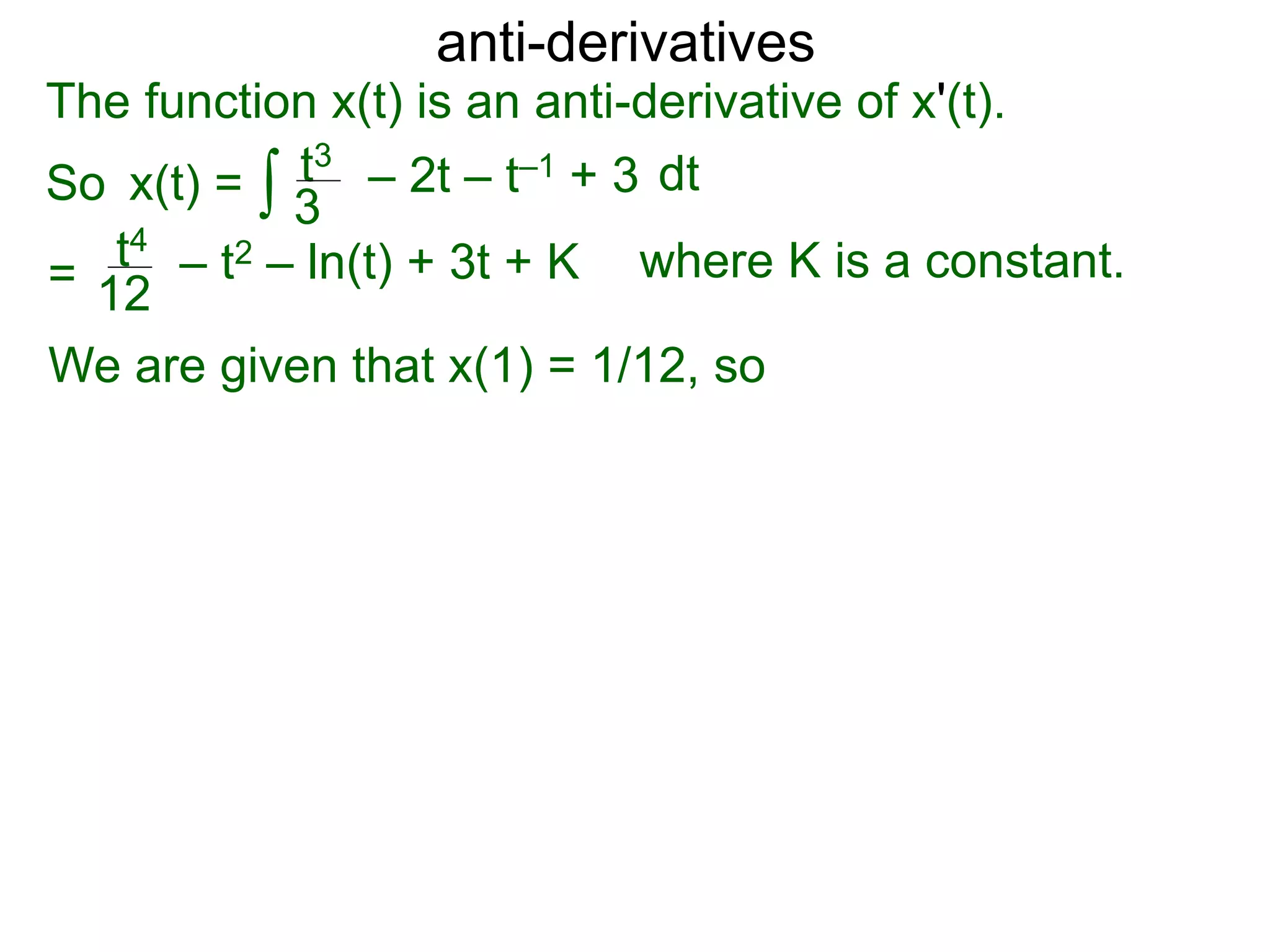

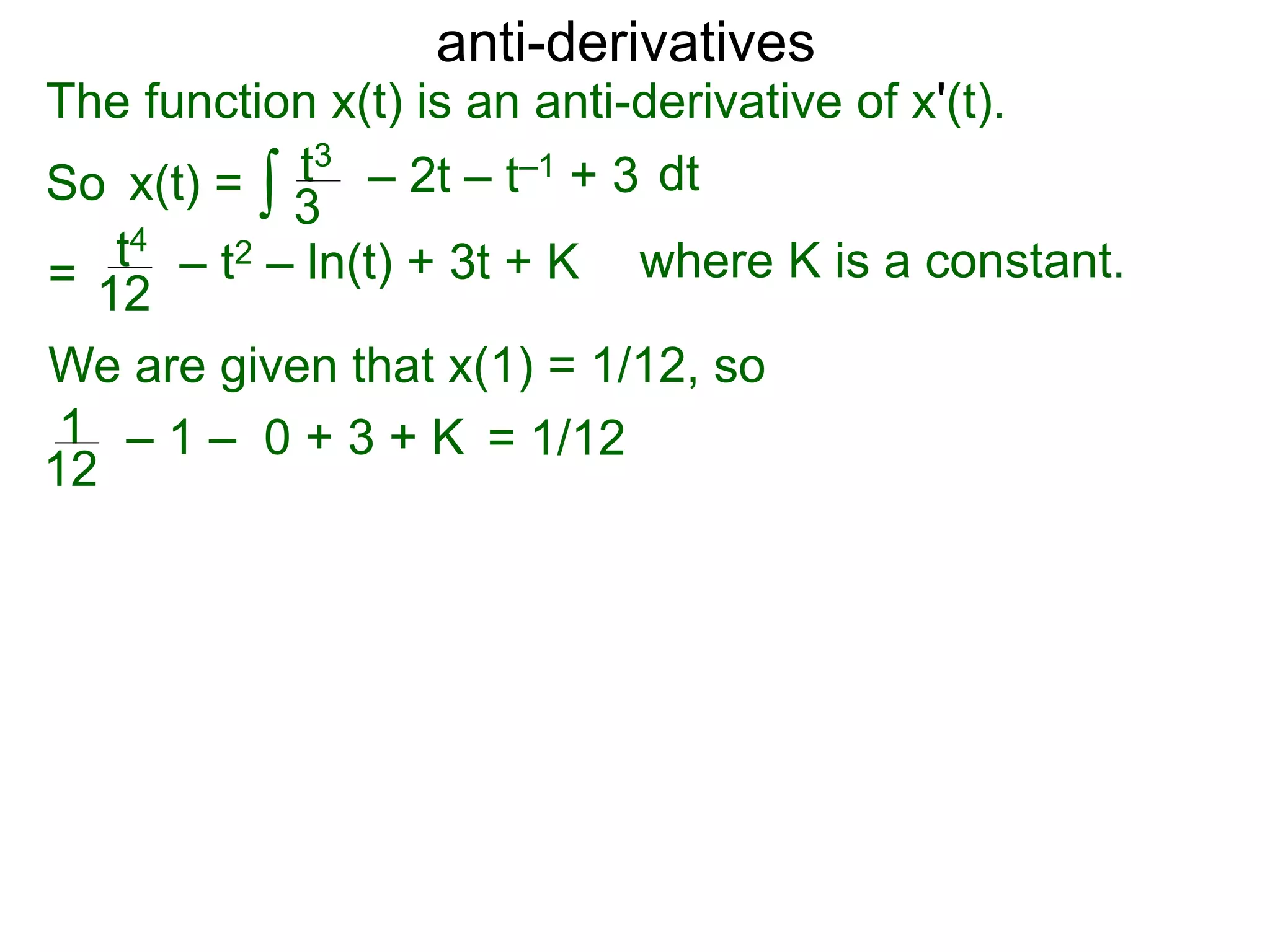

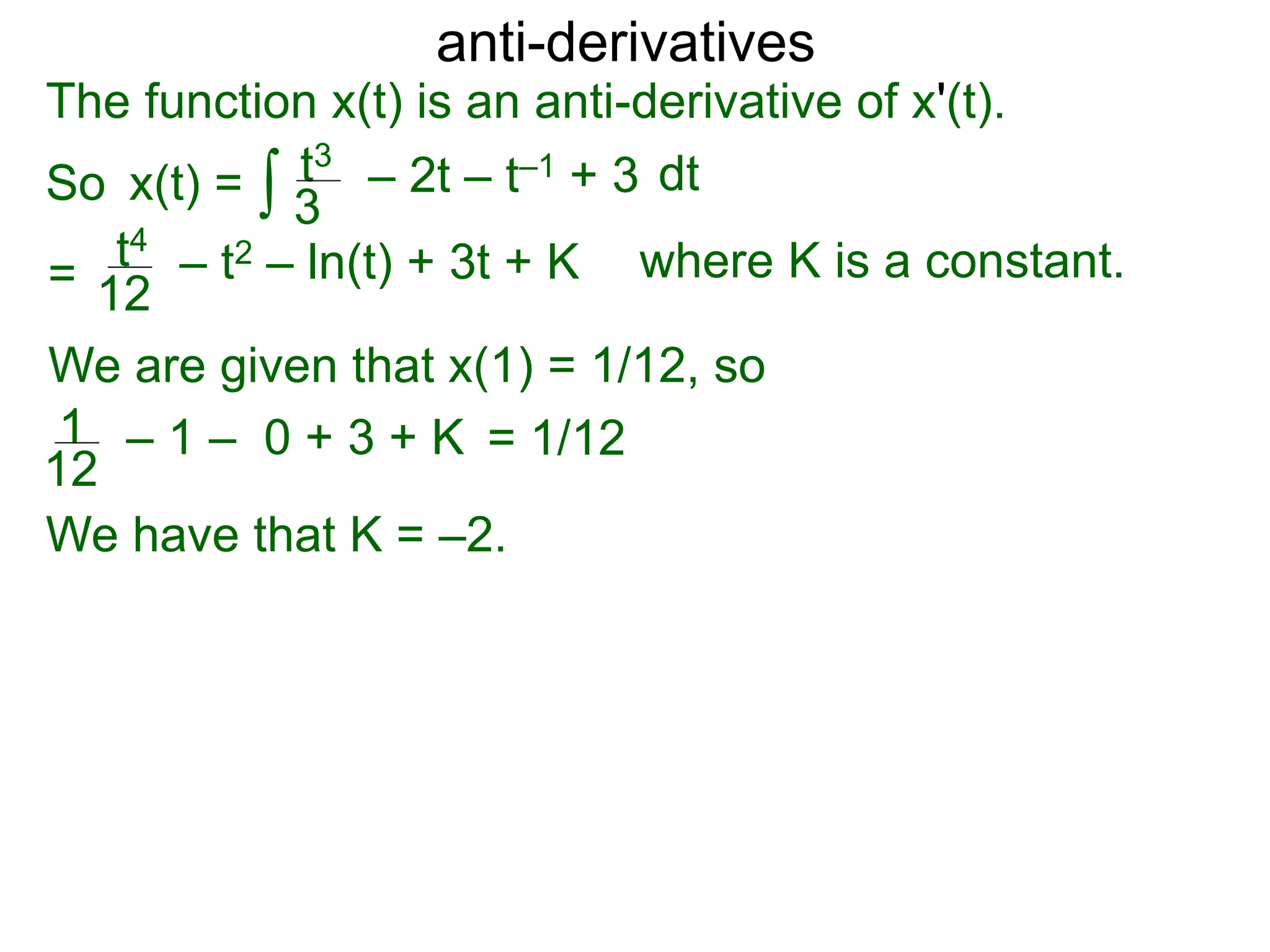

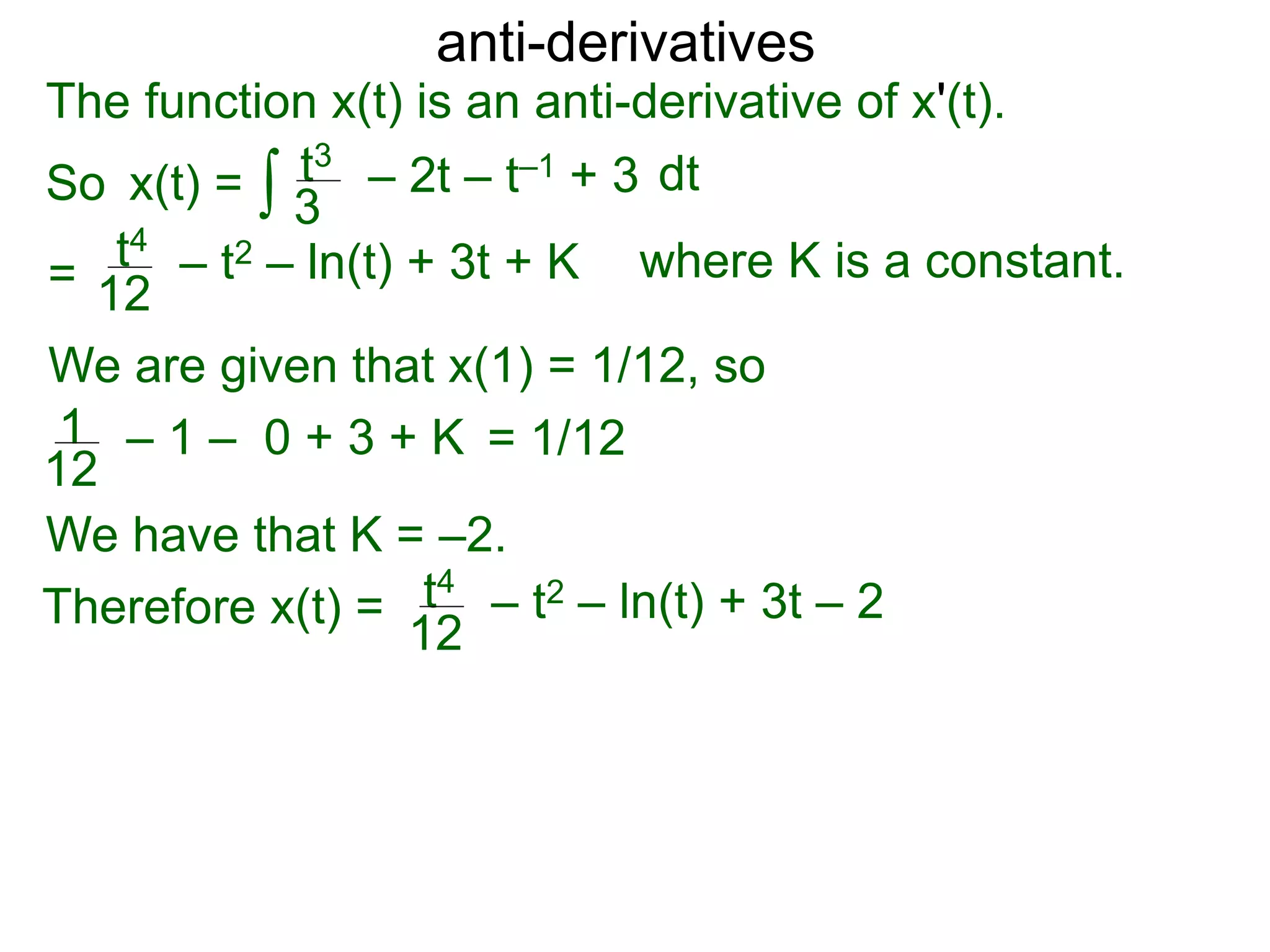

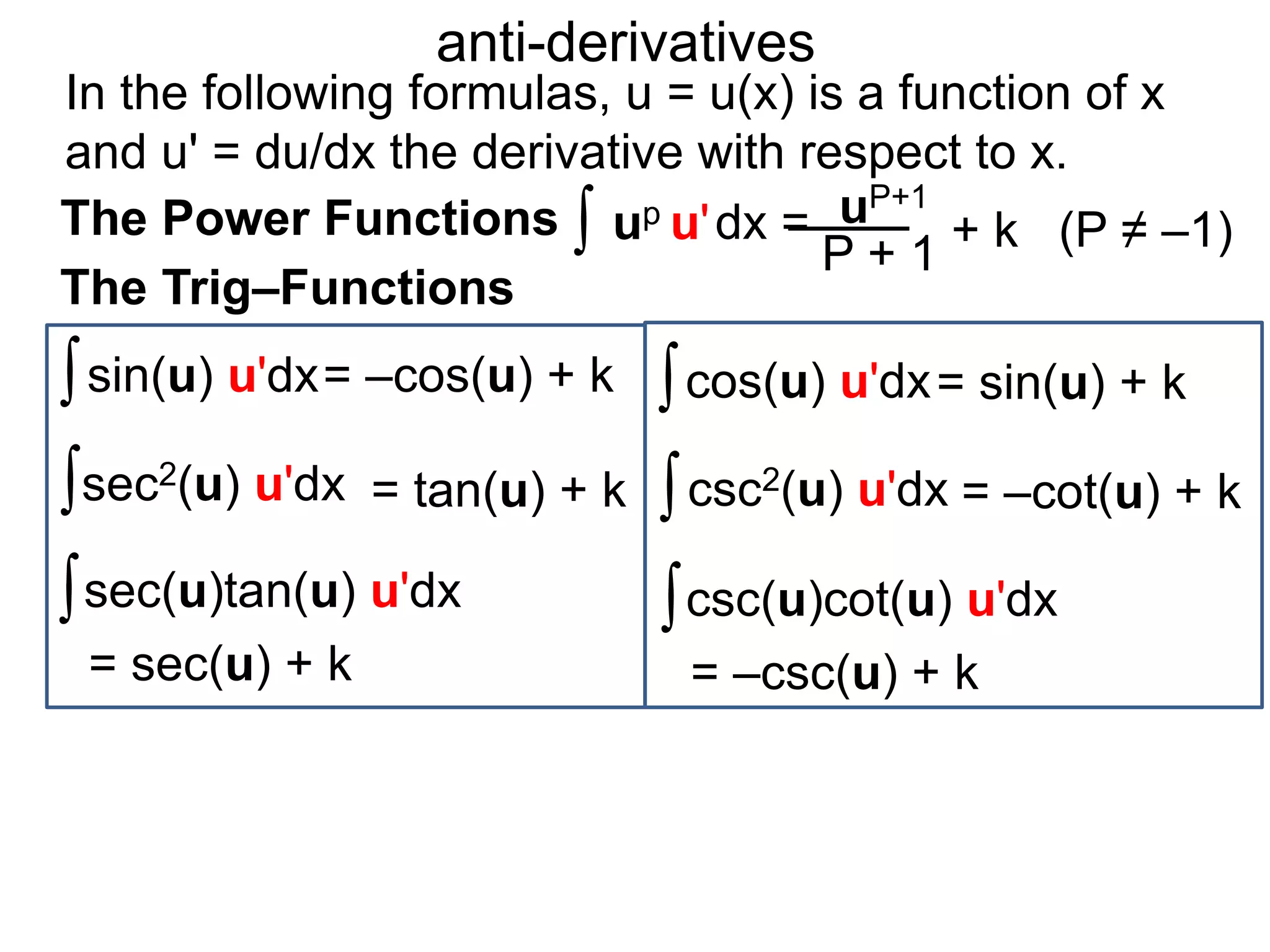

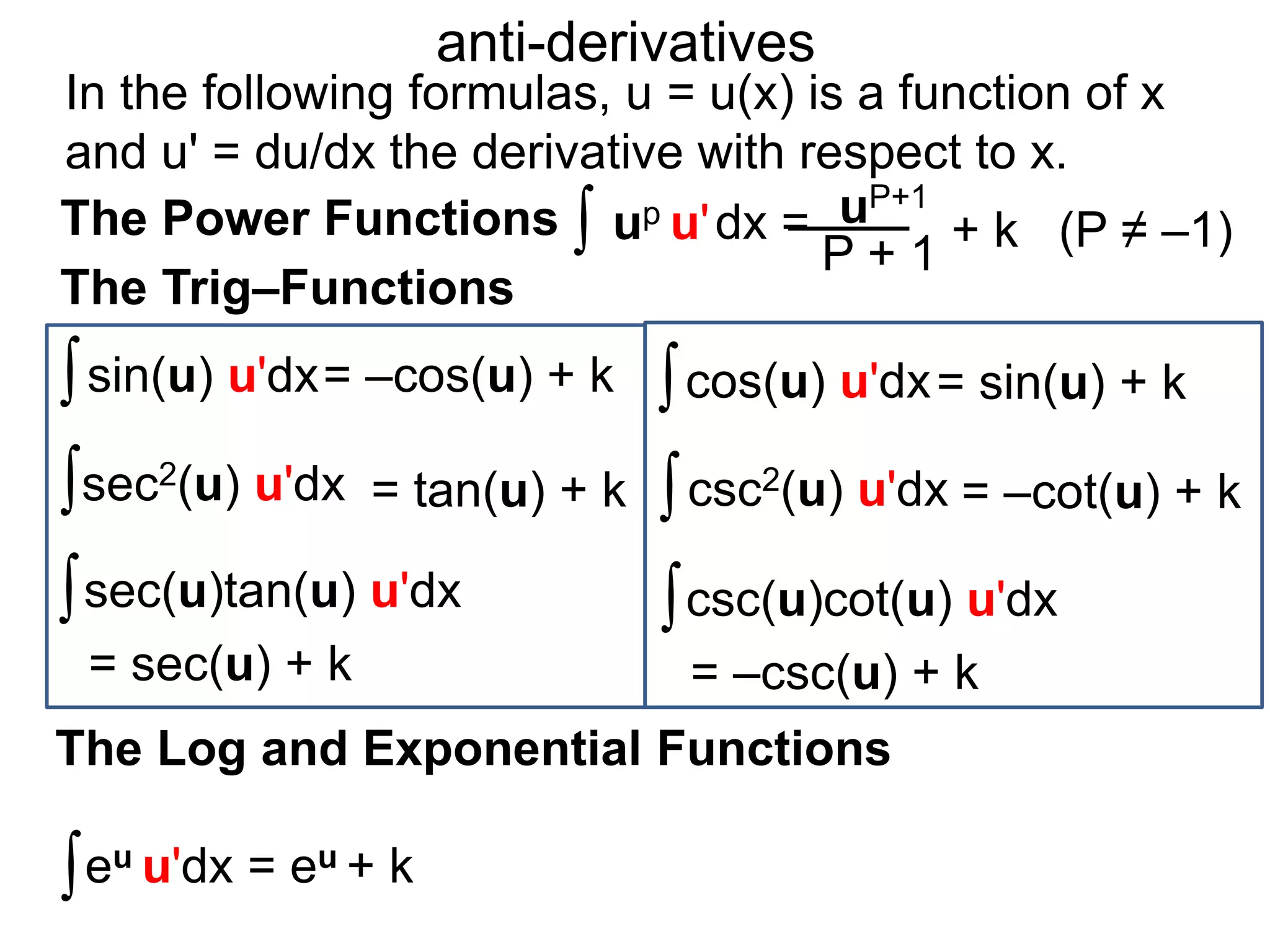

The document discusses anti-derivatives and integration. It defines an anti-derivative F(x) of a function f(x) as any function whose derivative is f(x). It also calls F(x) the indefinite integral of f(x). The document outlines basic integration rules for adding, subtracting and multiplying terms by constants when taking integrals. It provides examples of integrals of common functions and explains that the integration constant k positions the graph of the anti-derivative F(x).

![The Substitution Method

(f ○ u)'(x) = [f(u(x))]'

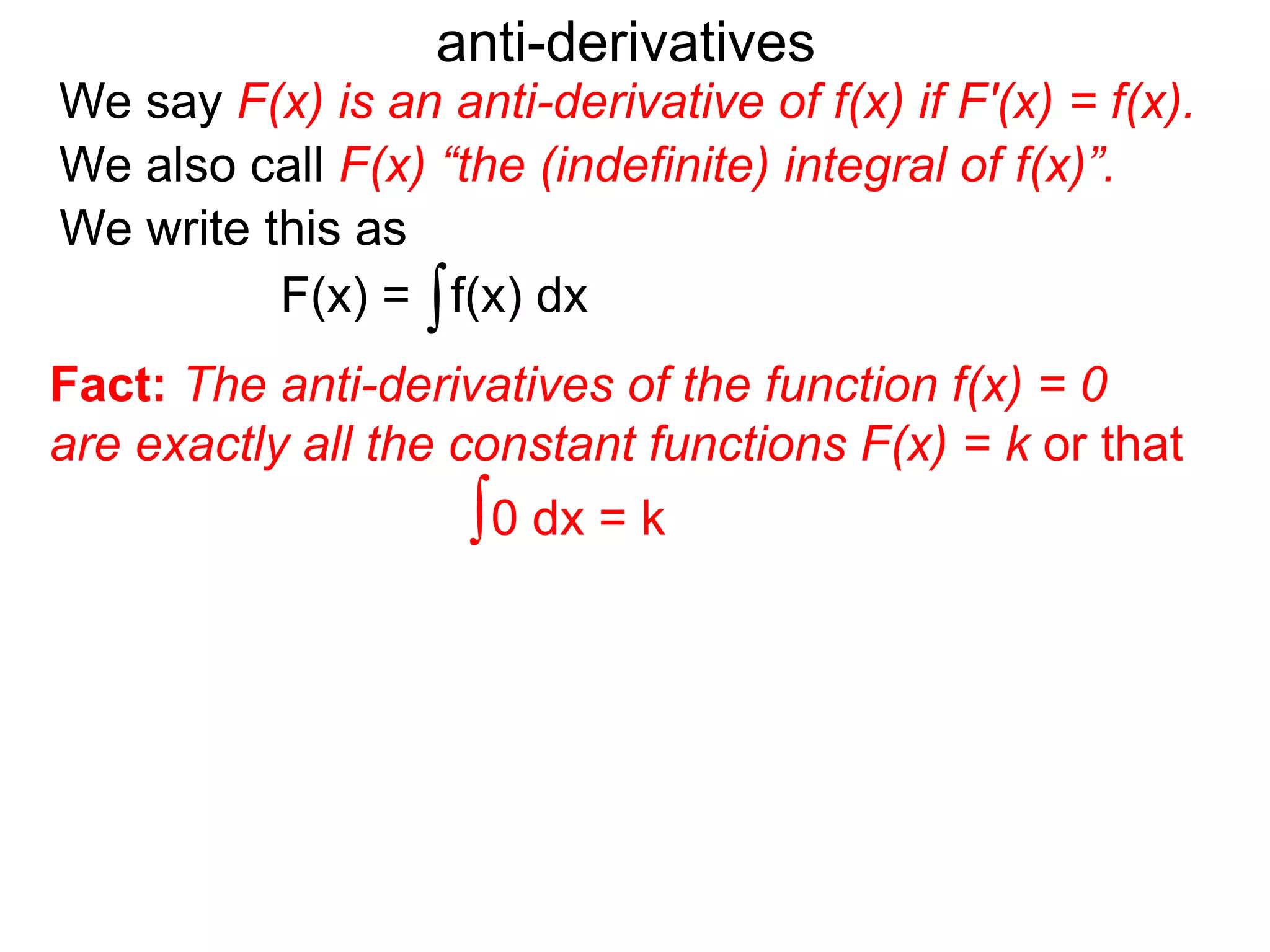

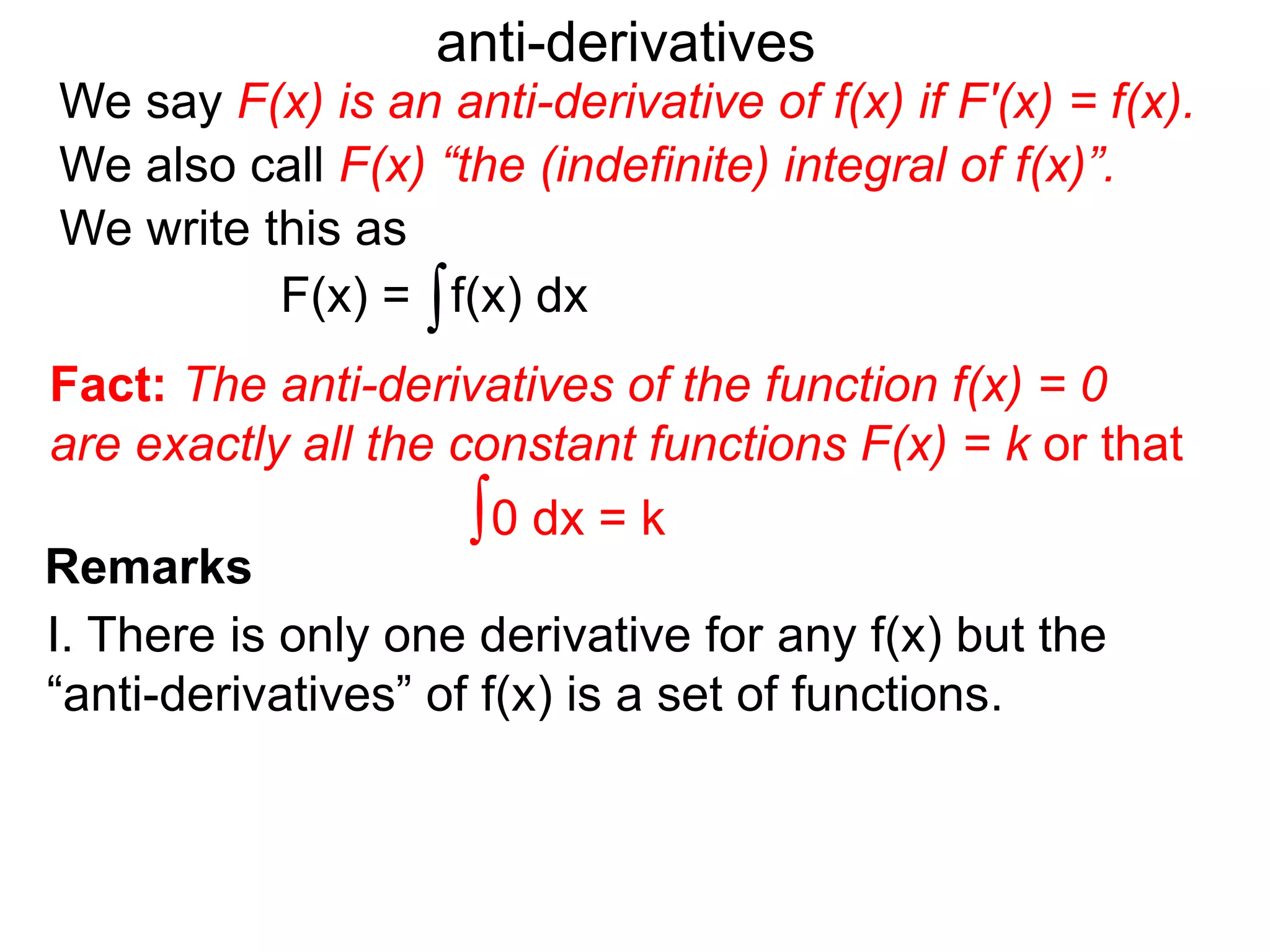

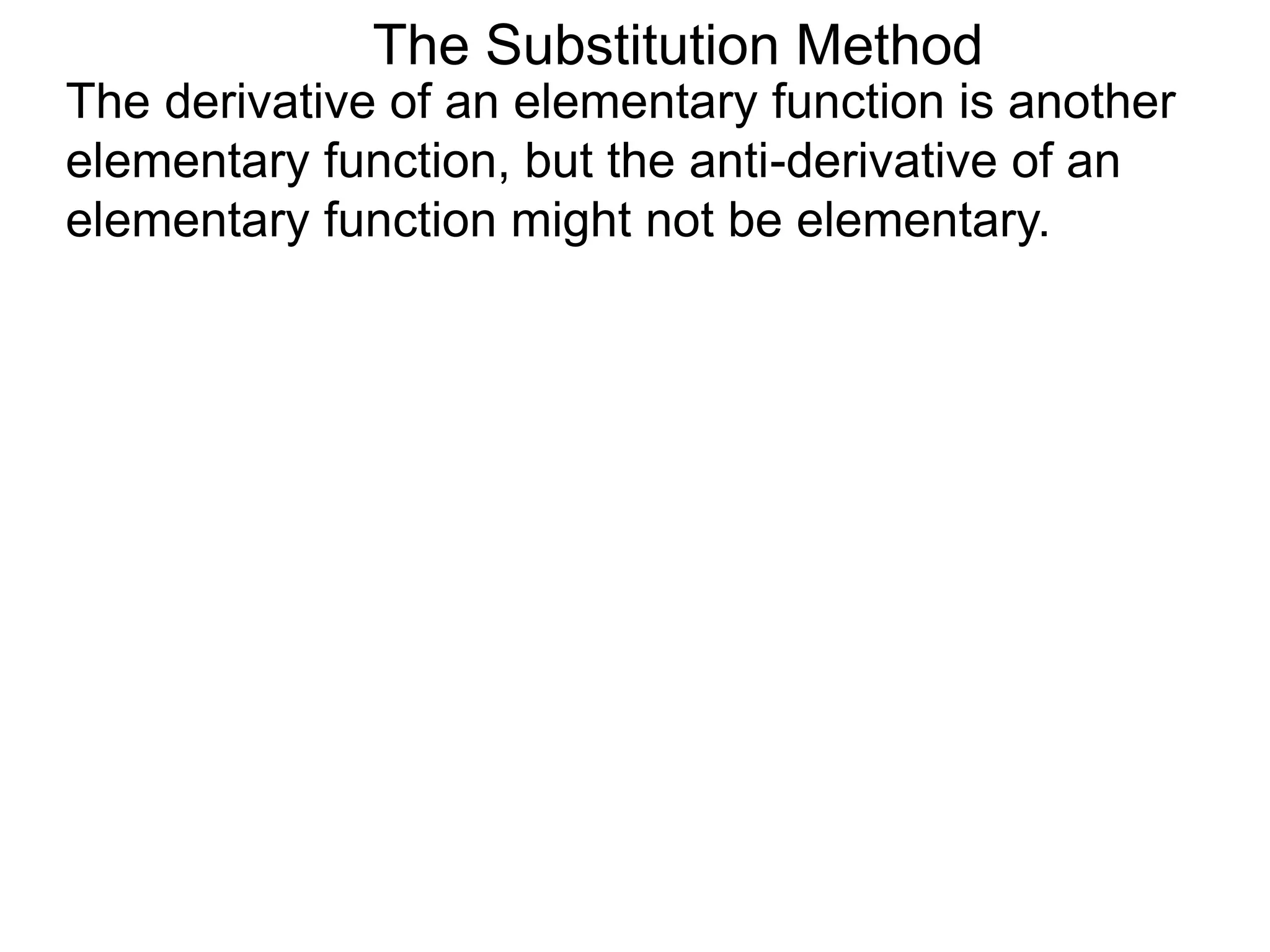

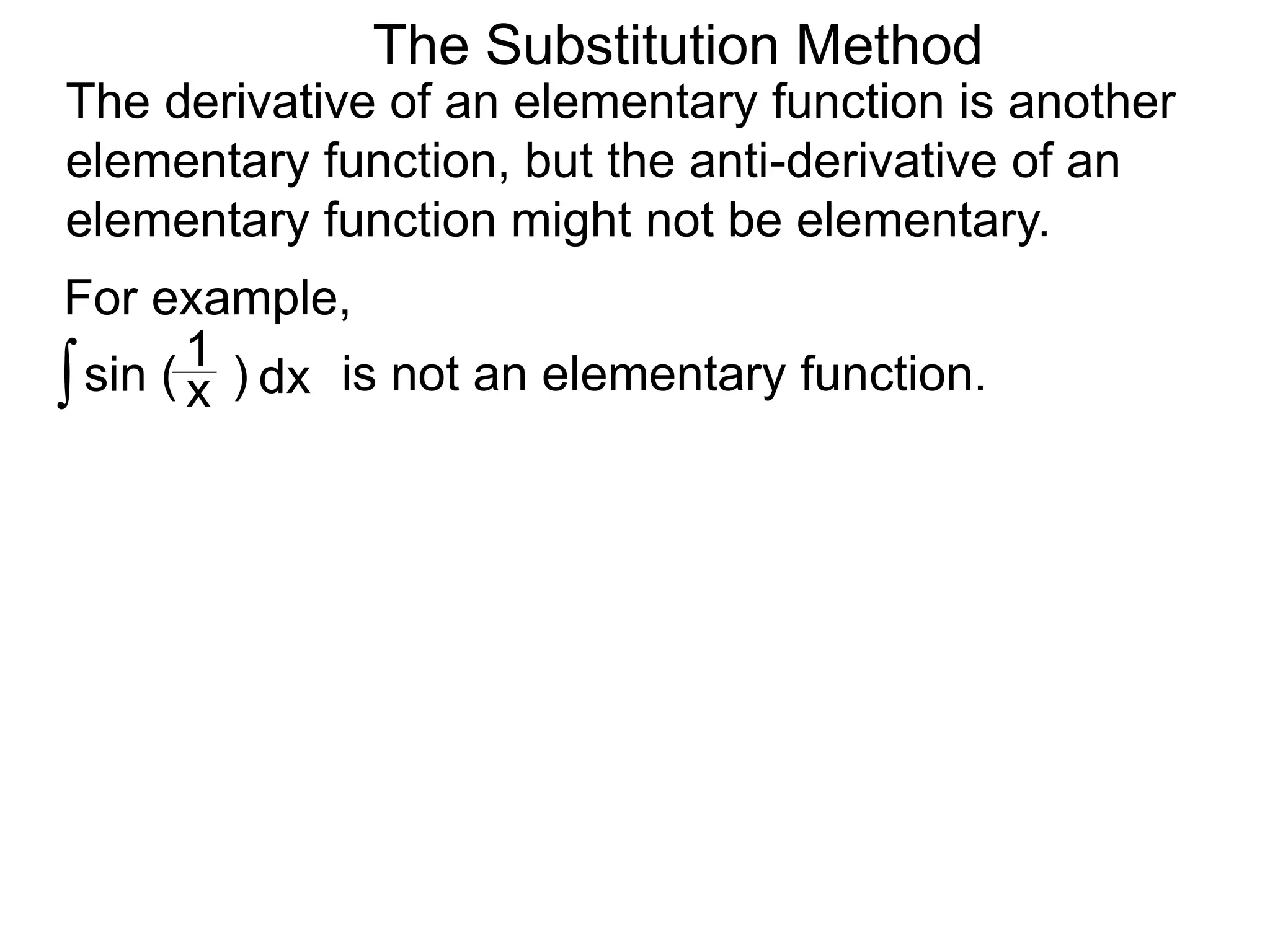

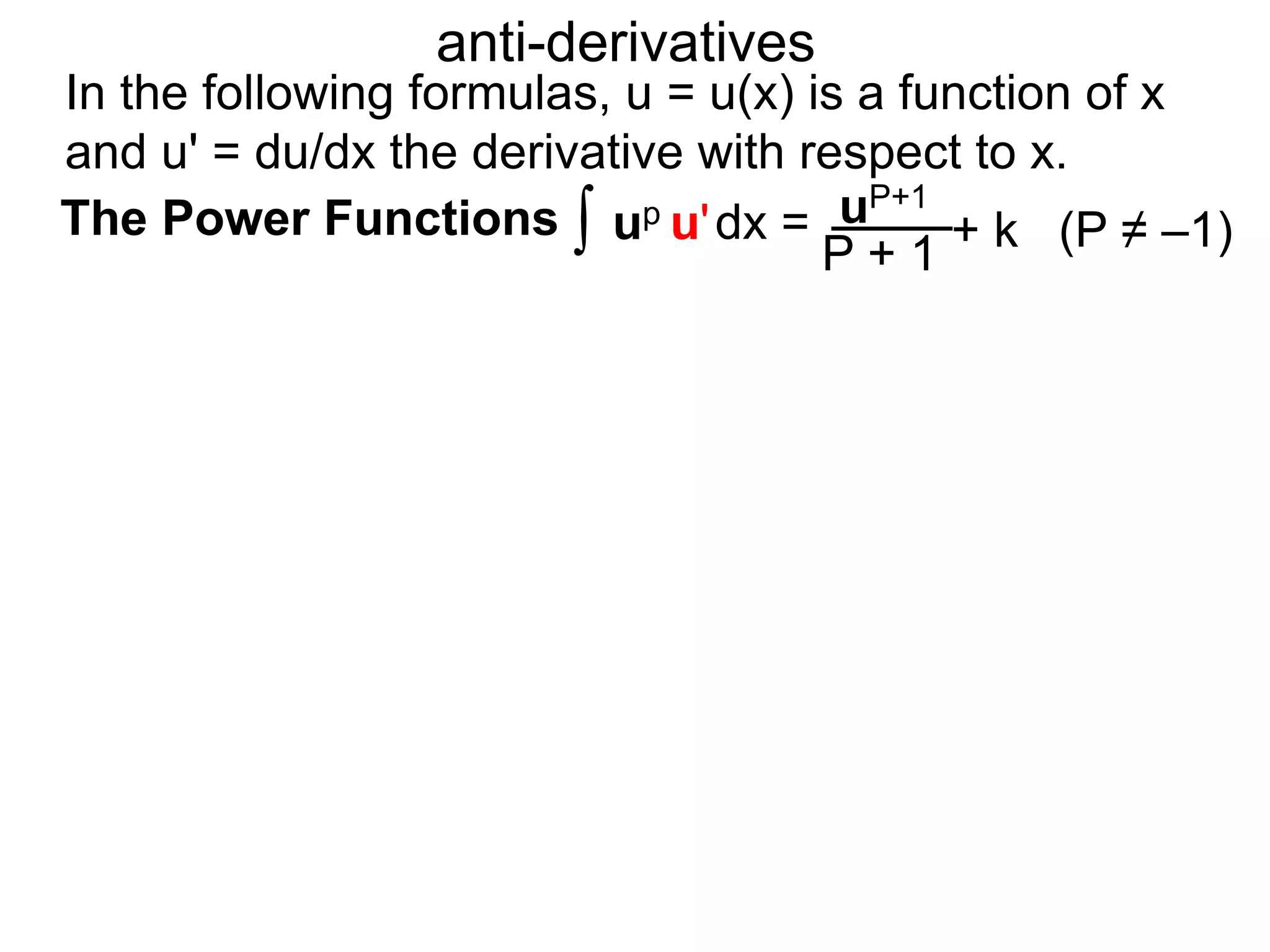

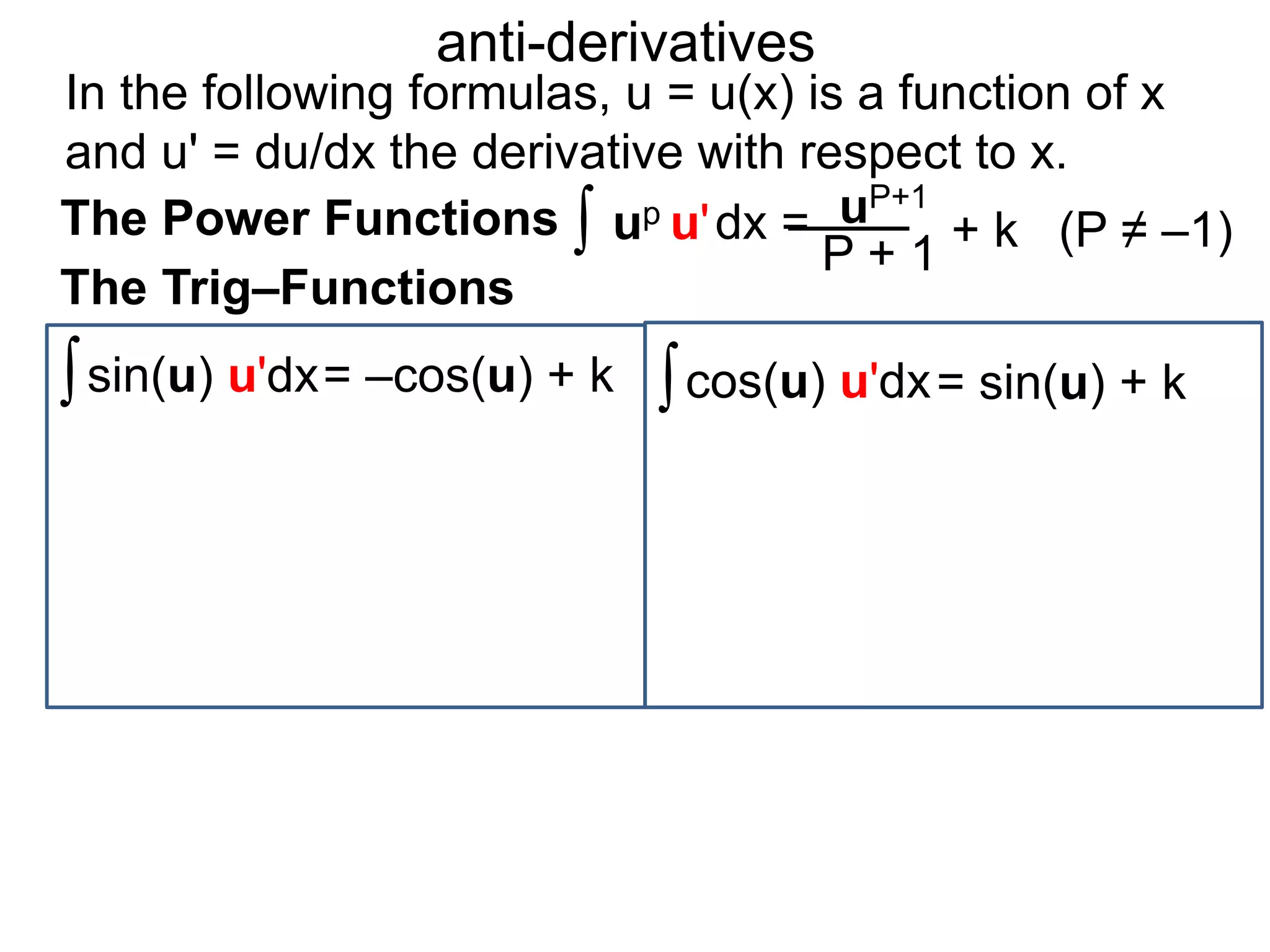

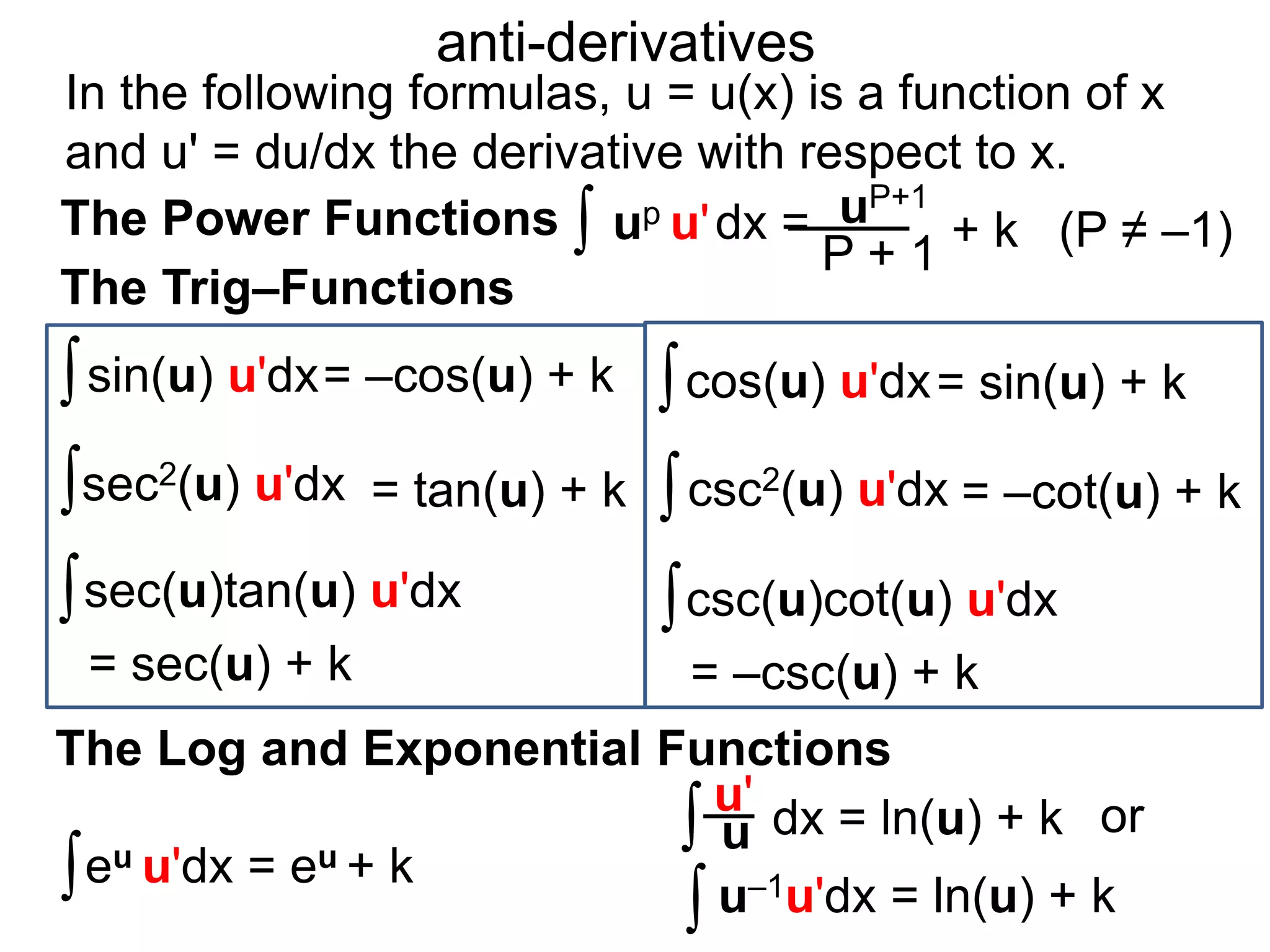

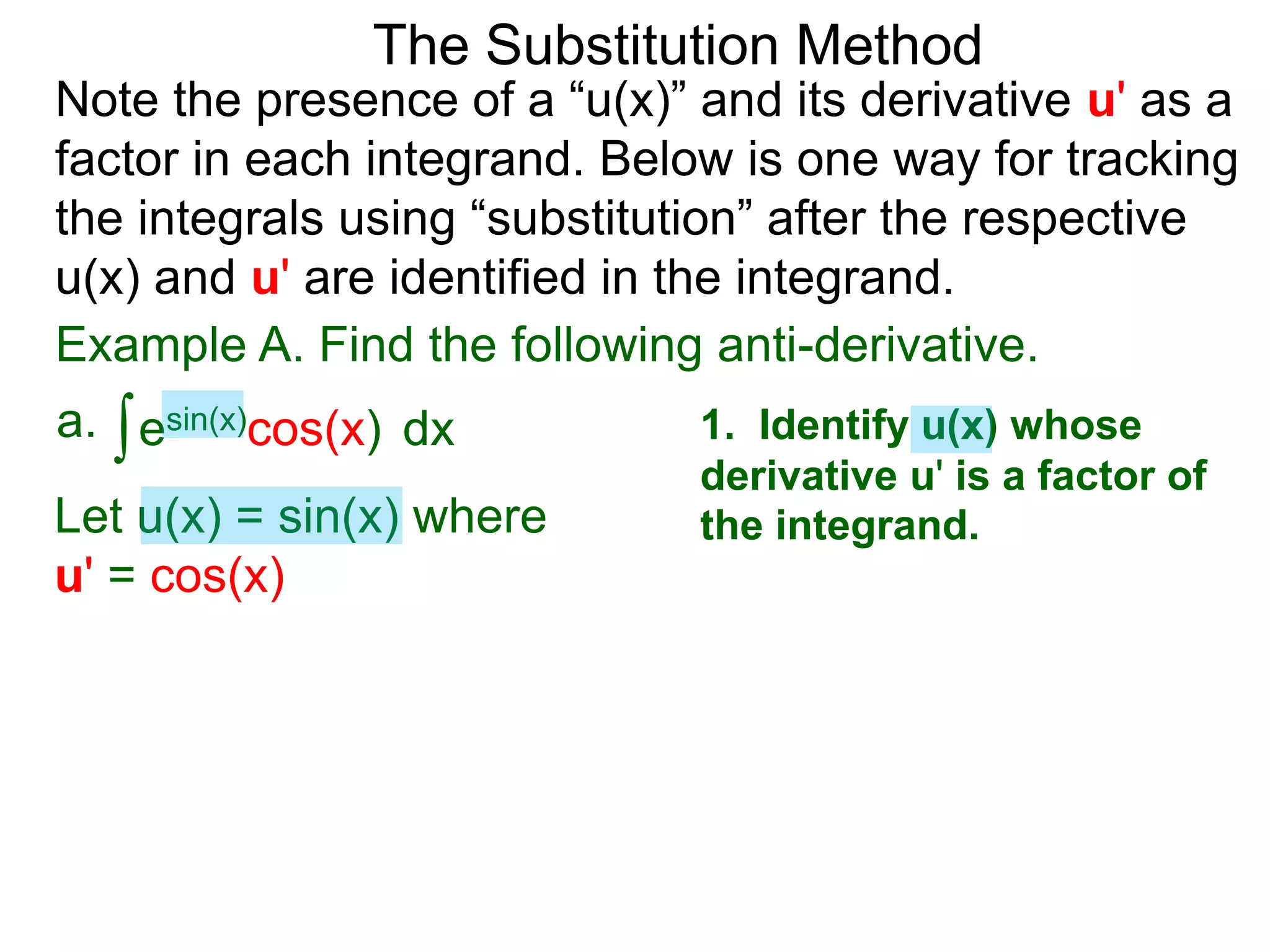

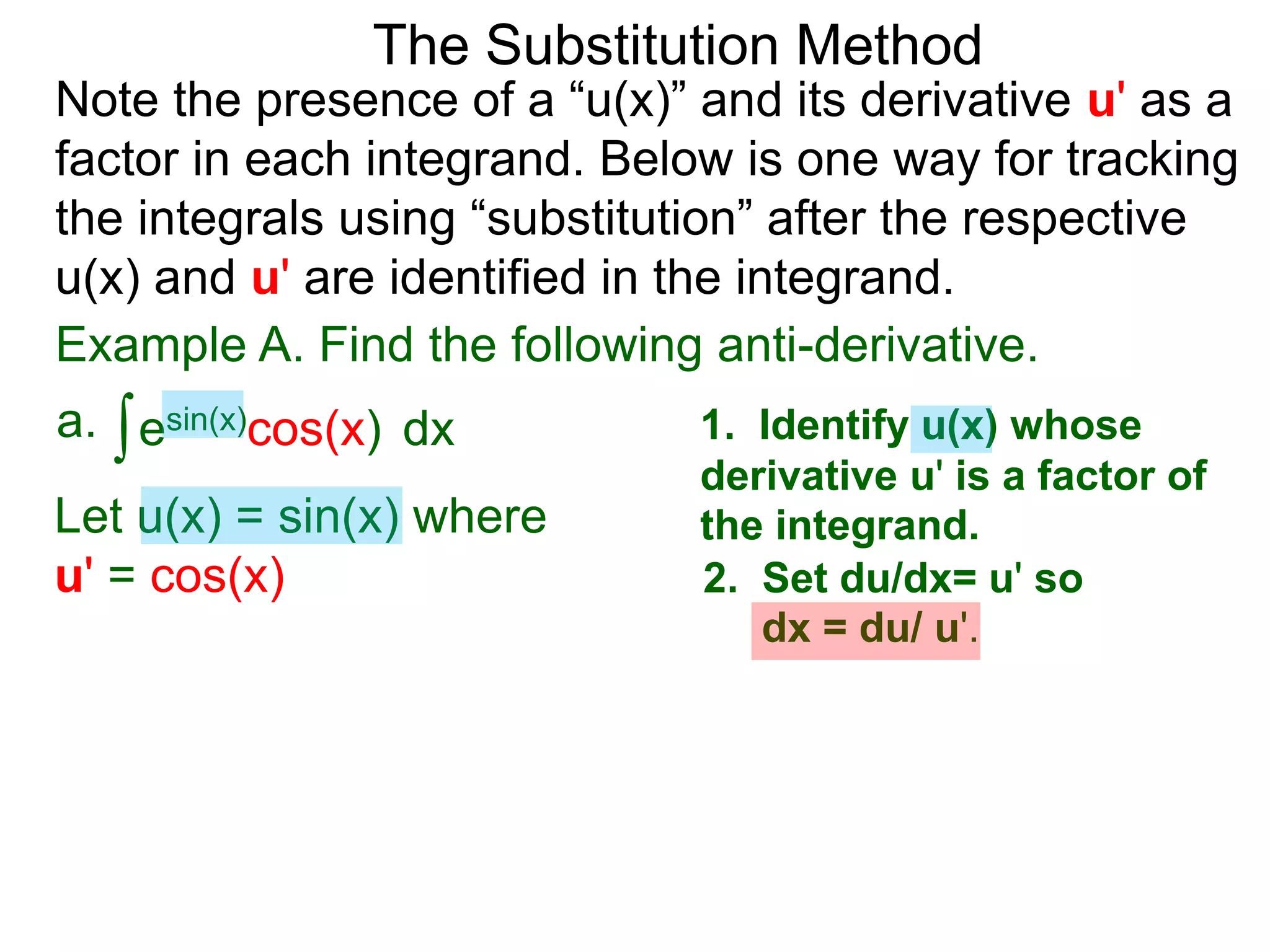

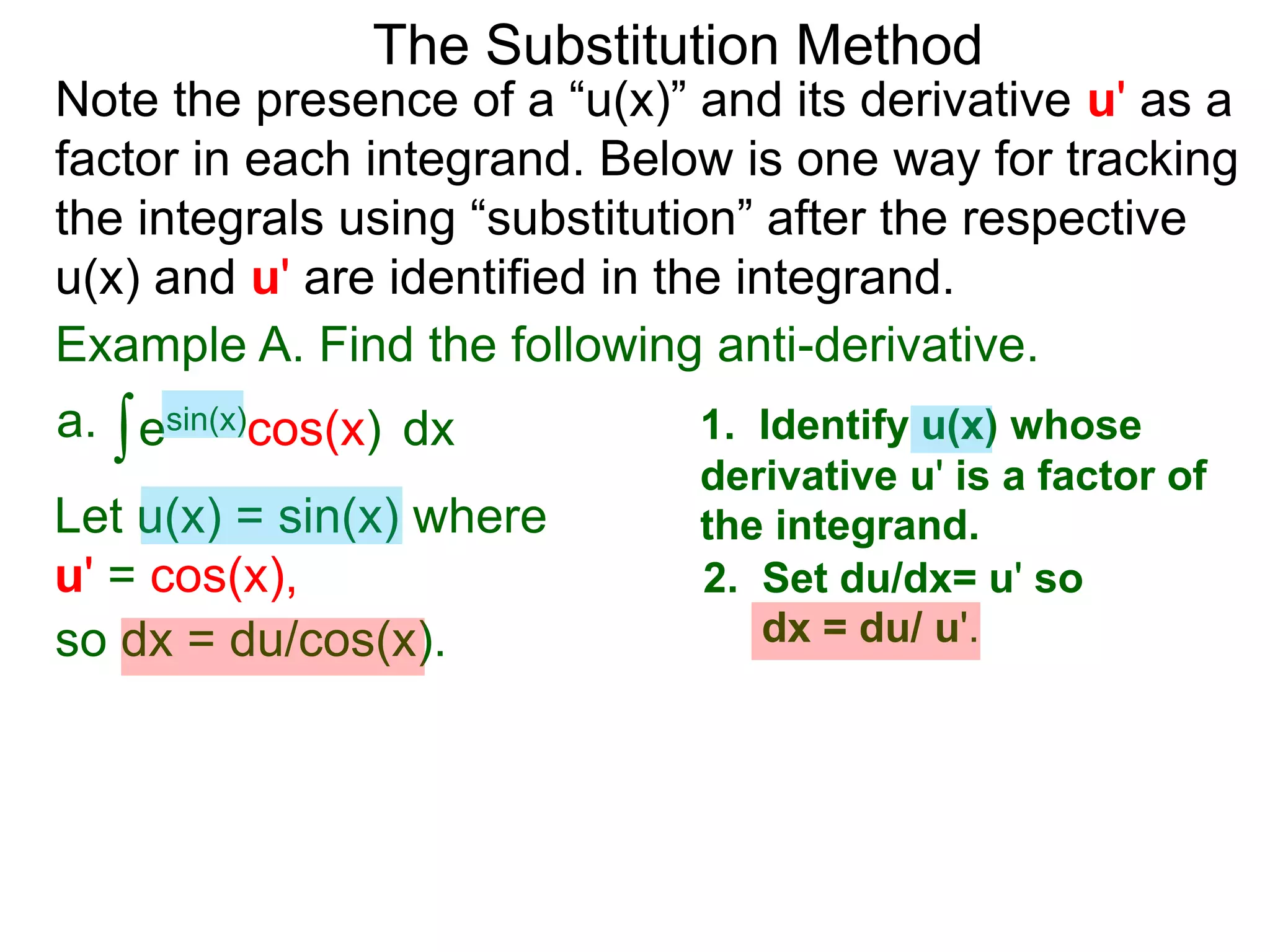

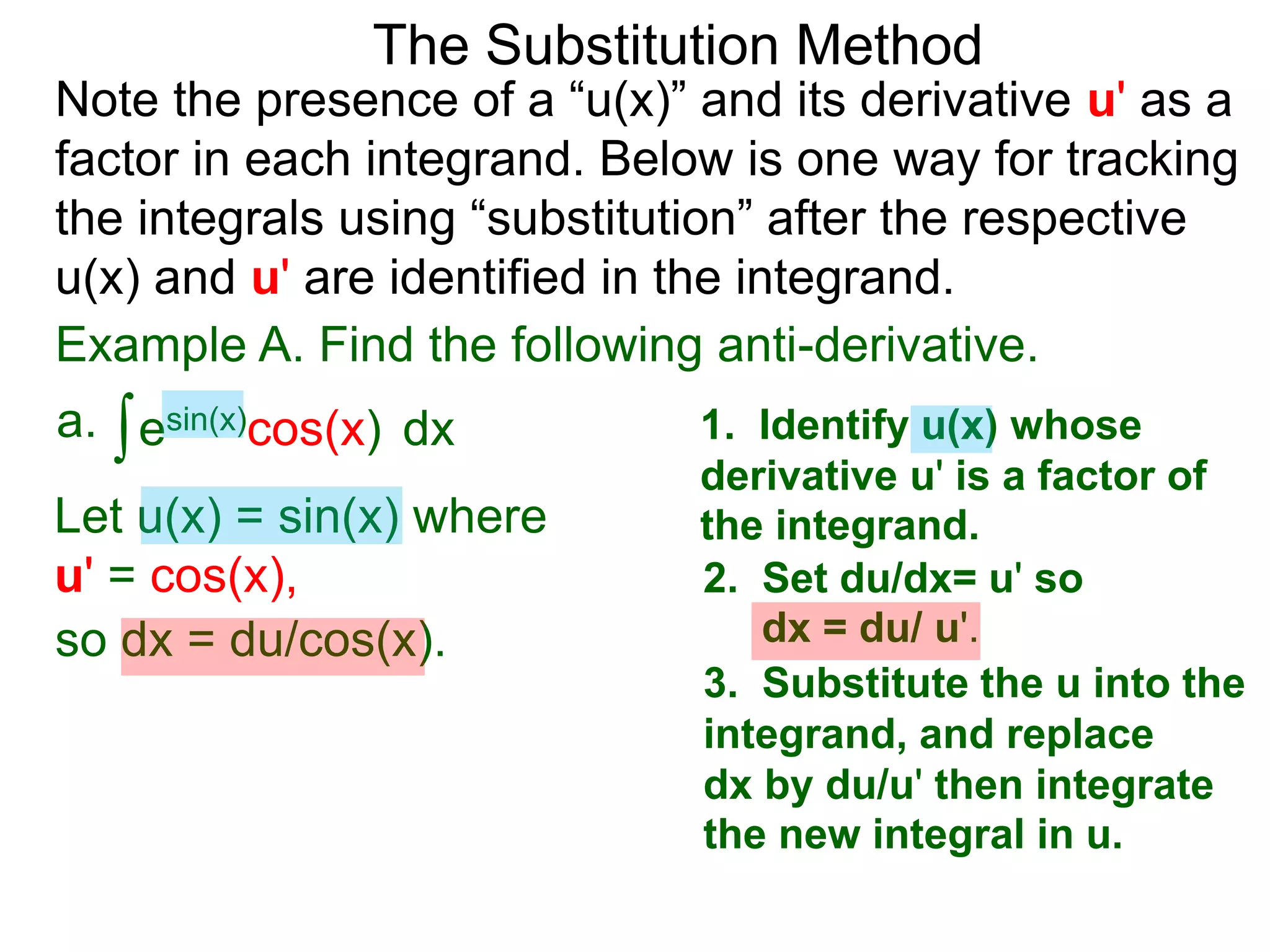

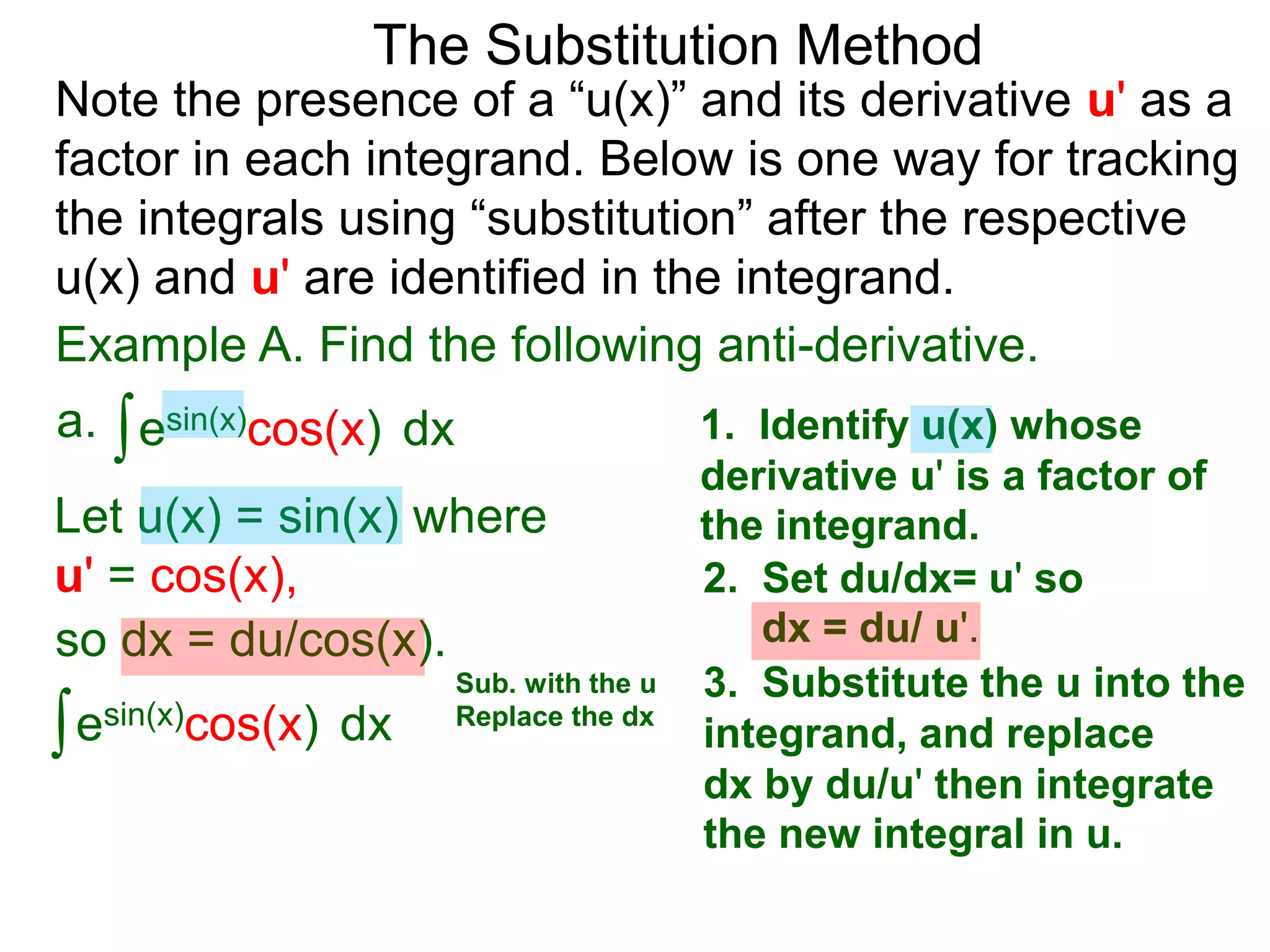

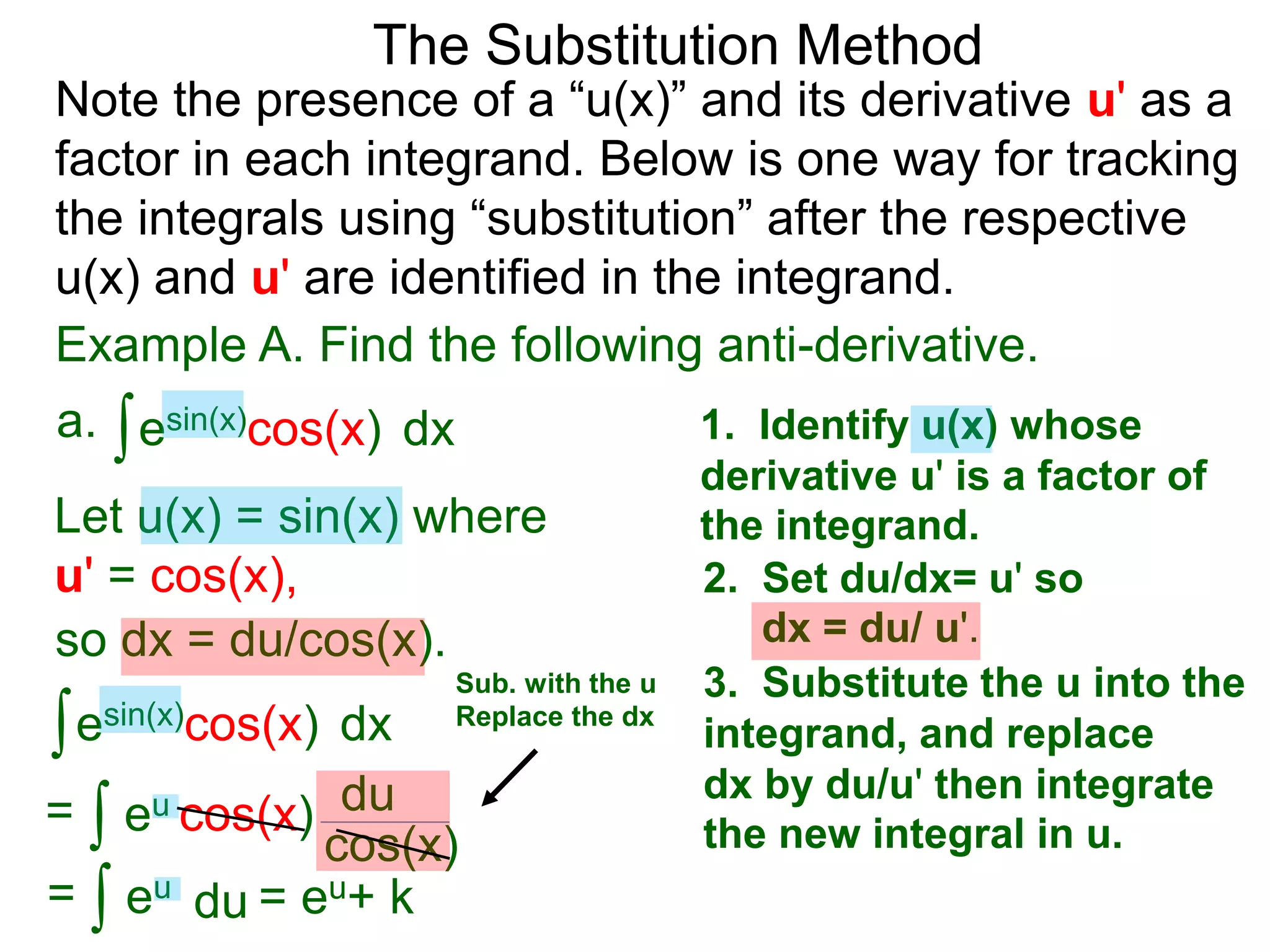

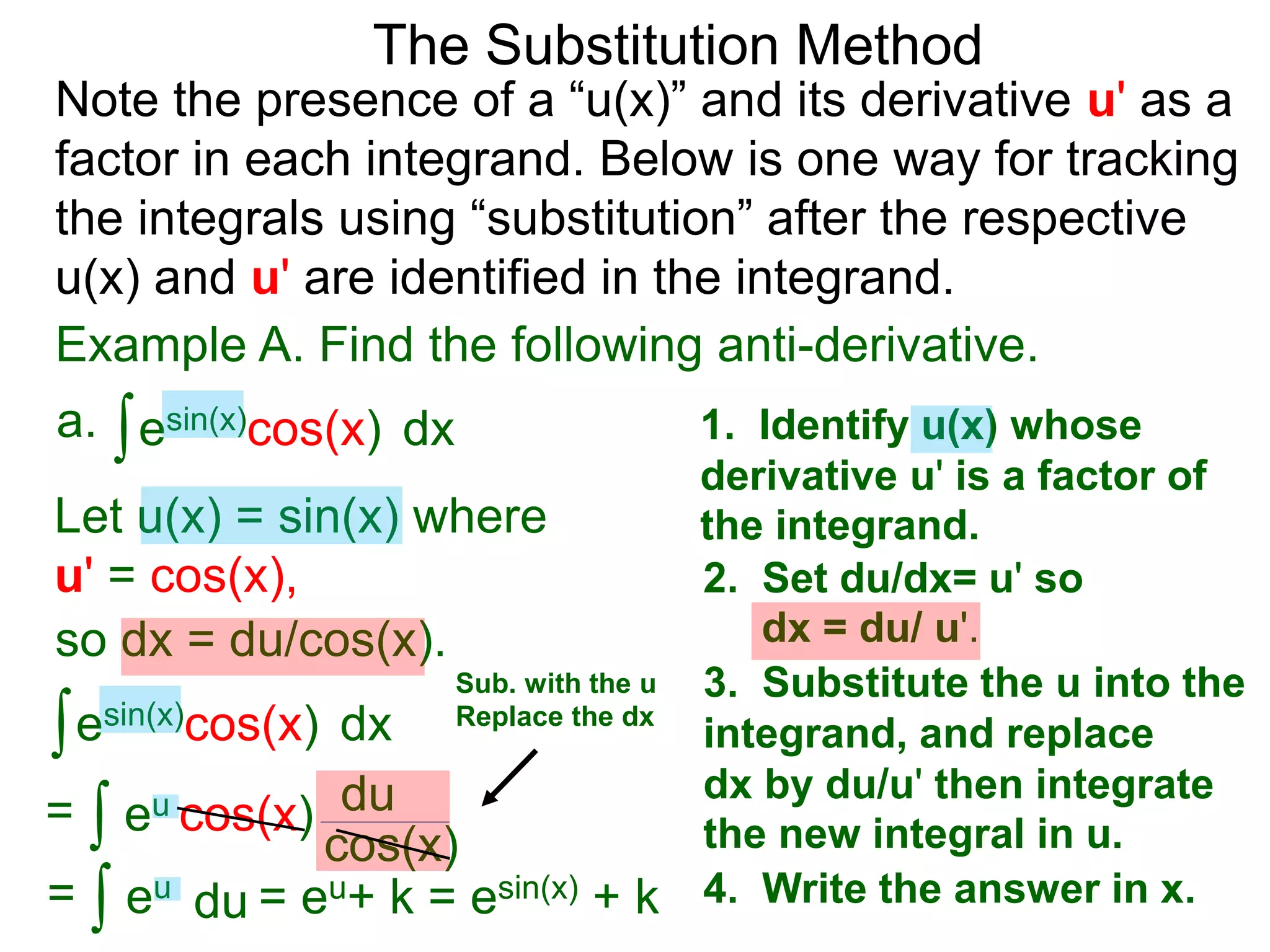

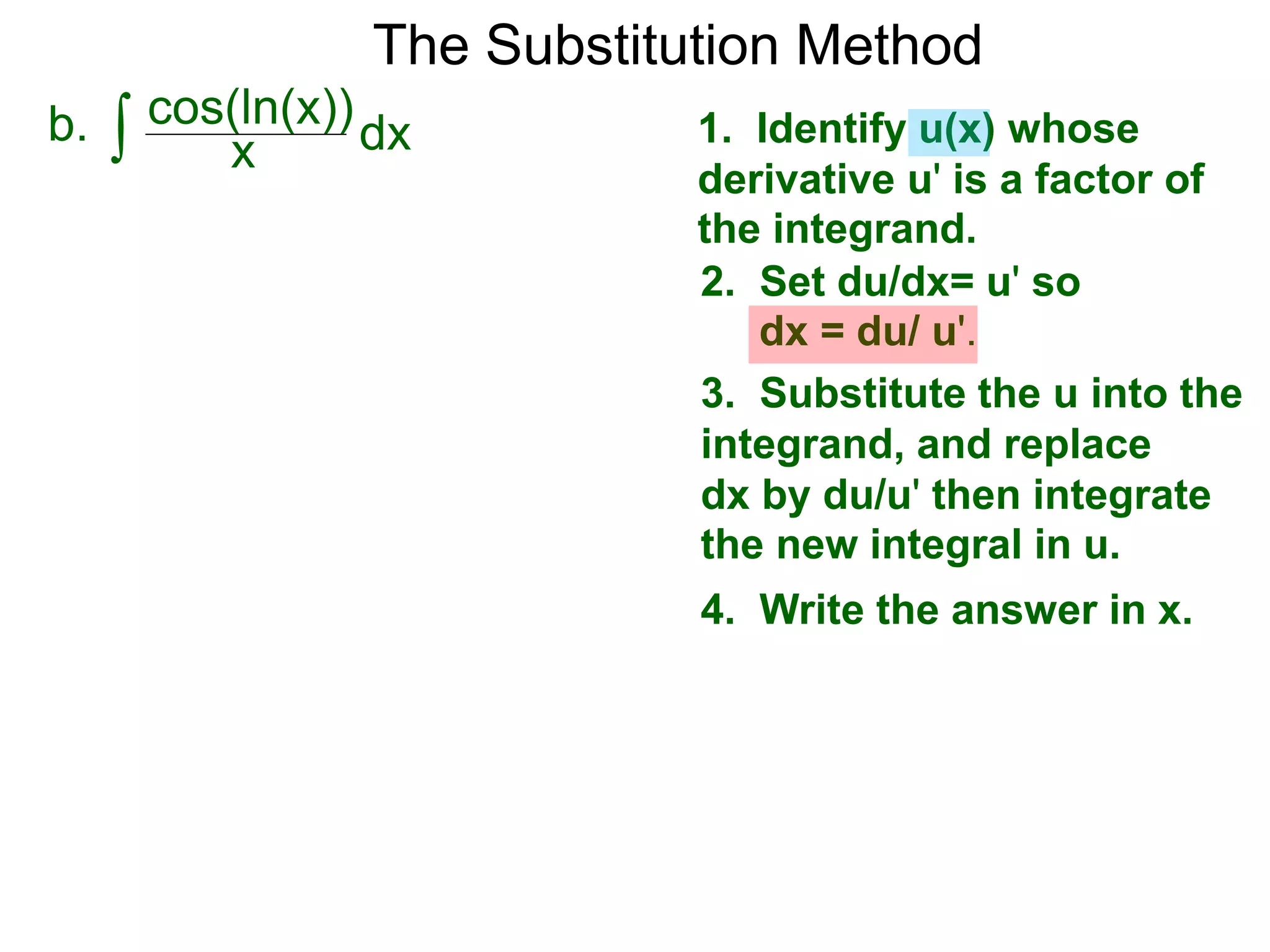

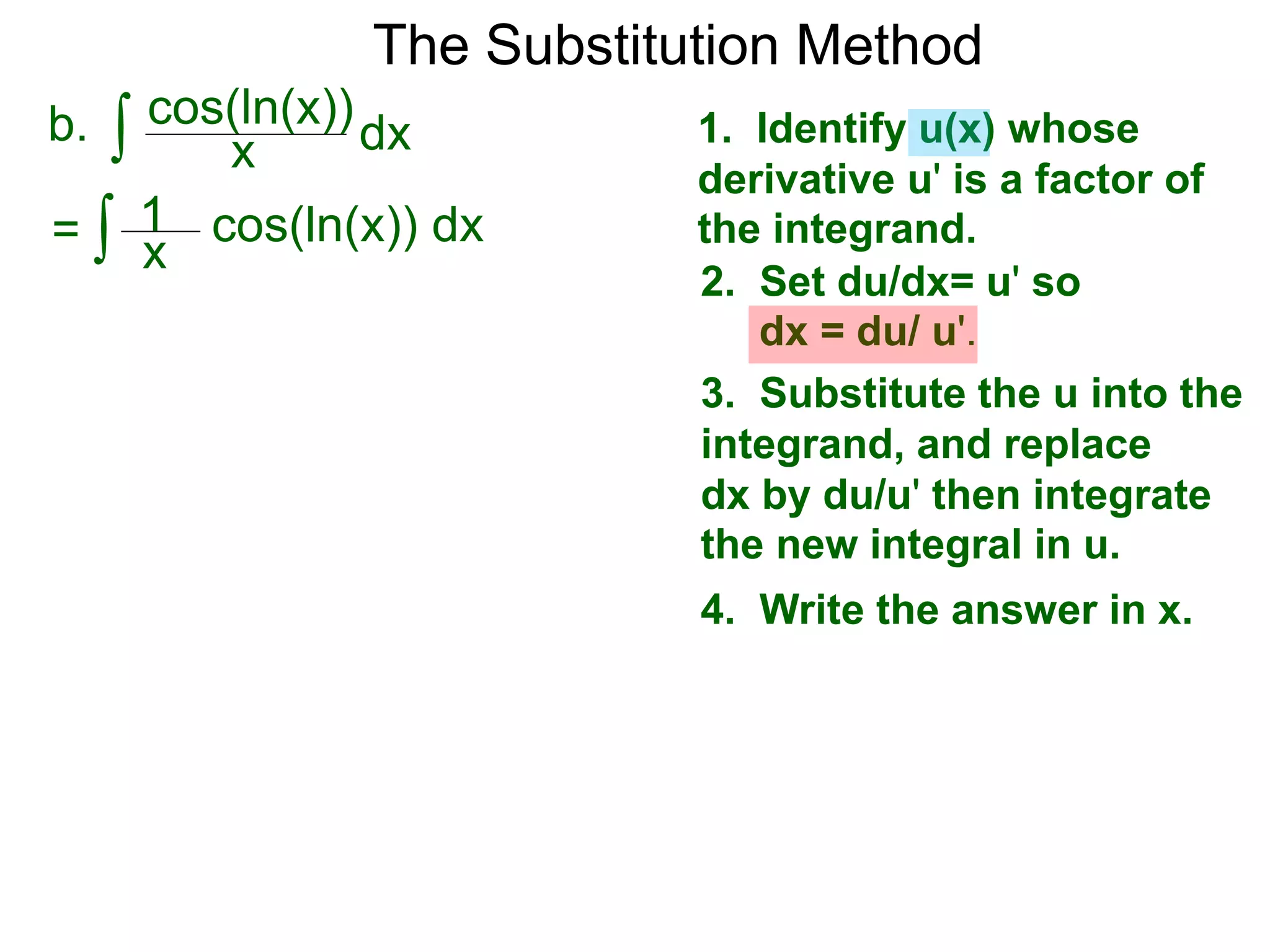

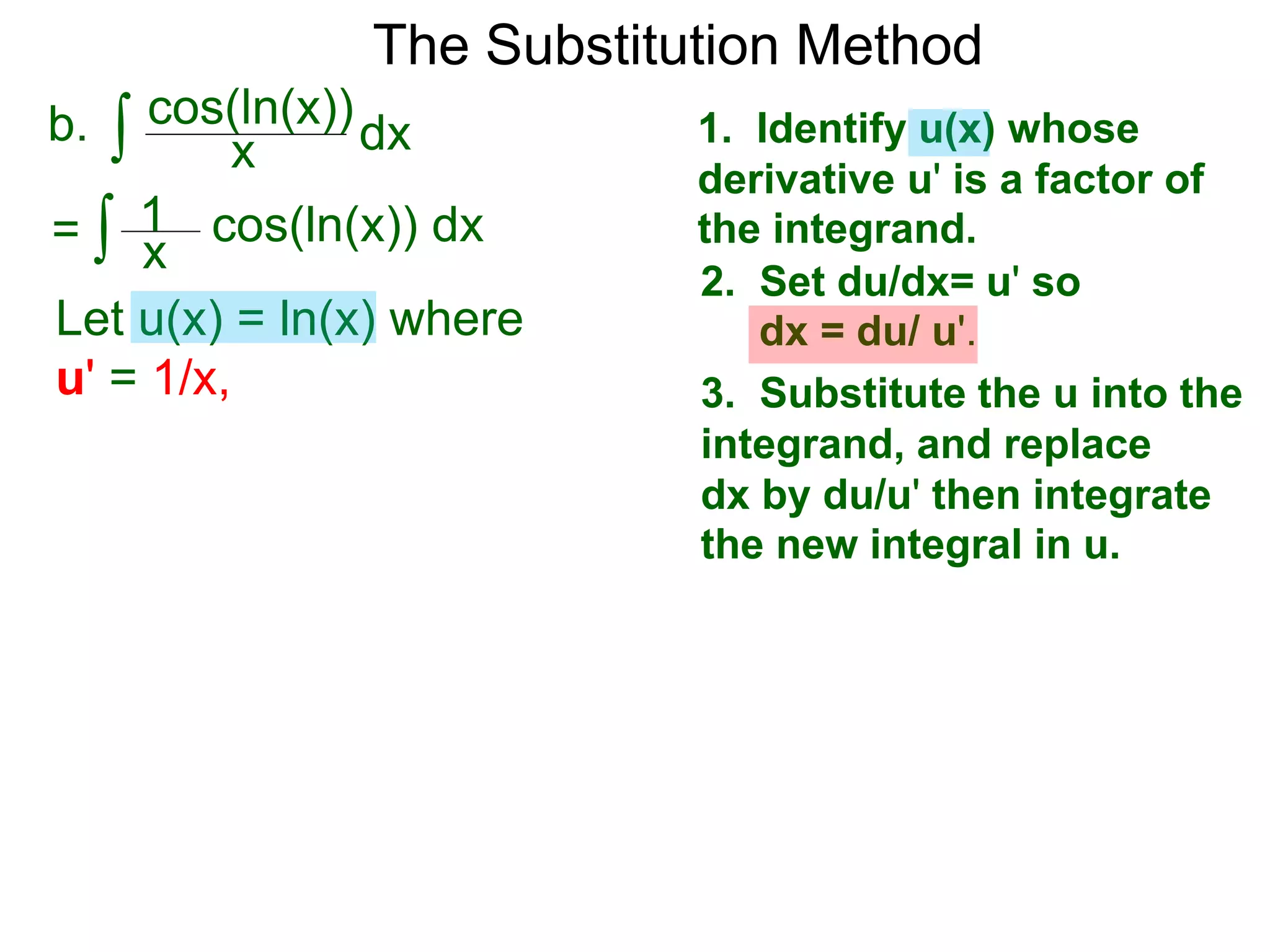

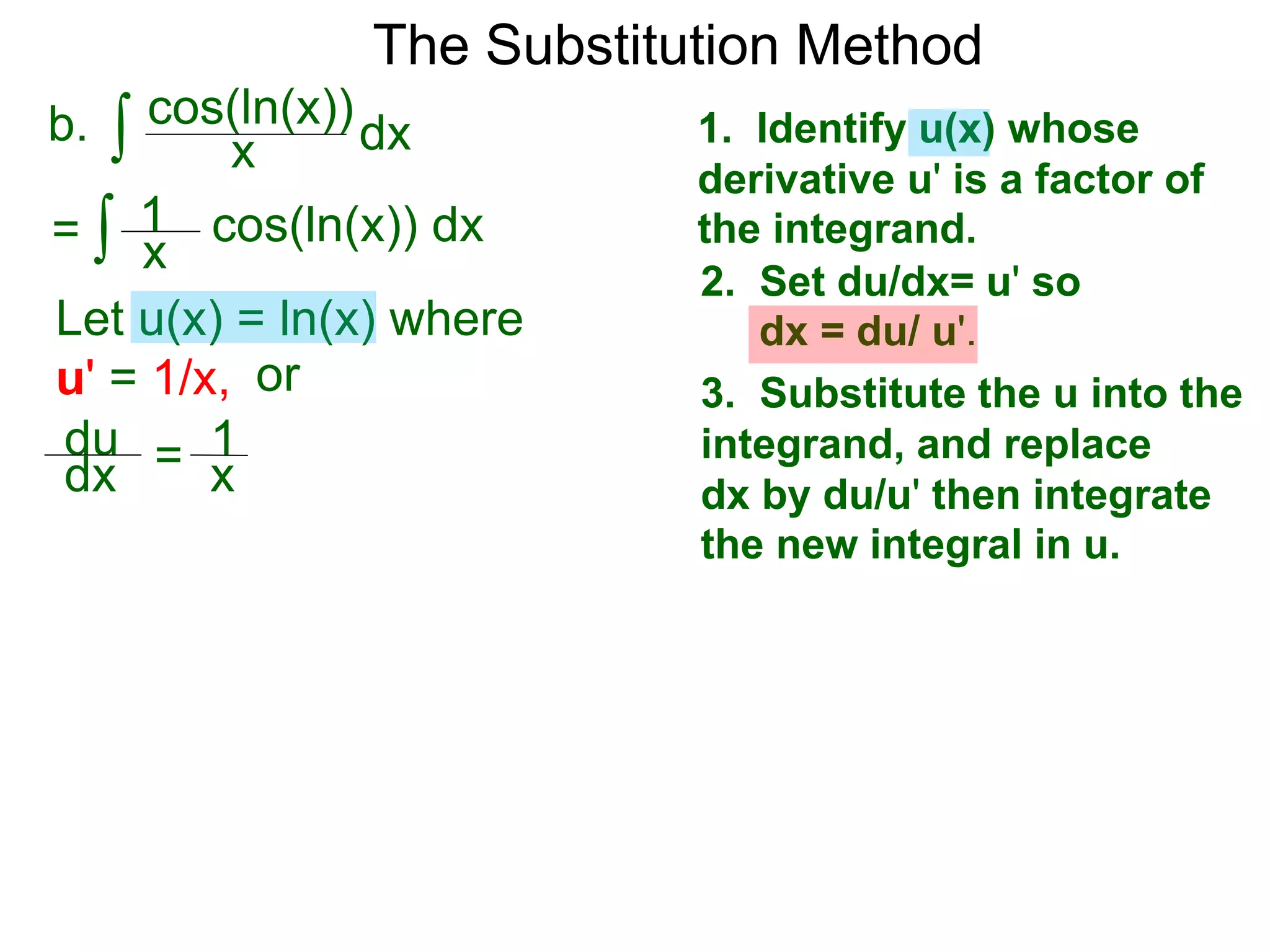

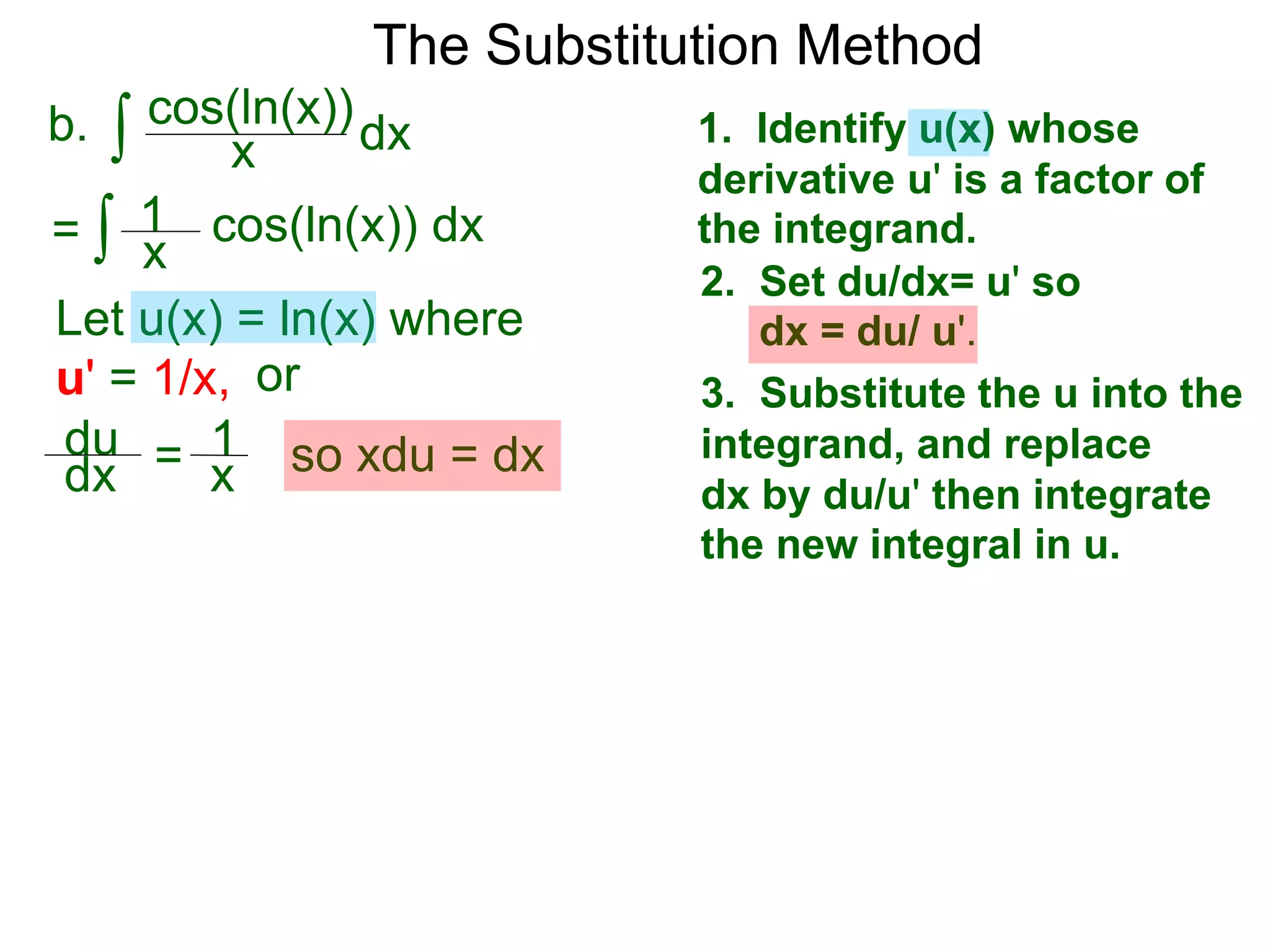

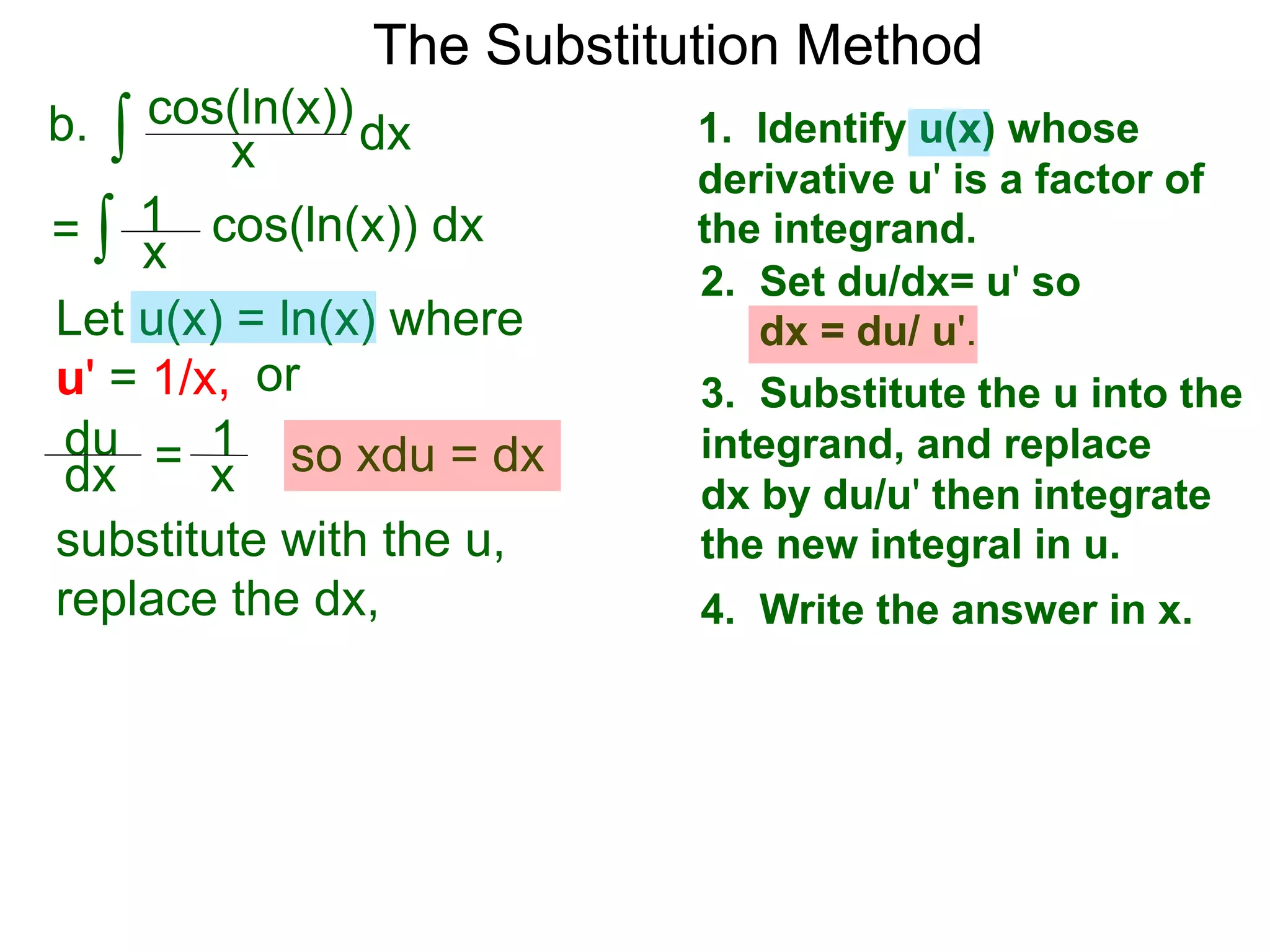

There are two main methods of integration,

the Substitution Method and Integration by Parts.

The Substitution Method reverses the Chain Rule

and Integration by Parts unwinds the Product Rule.

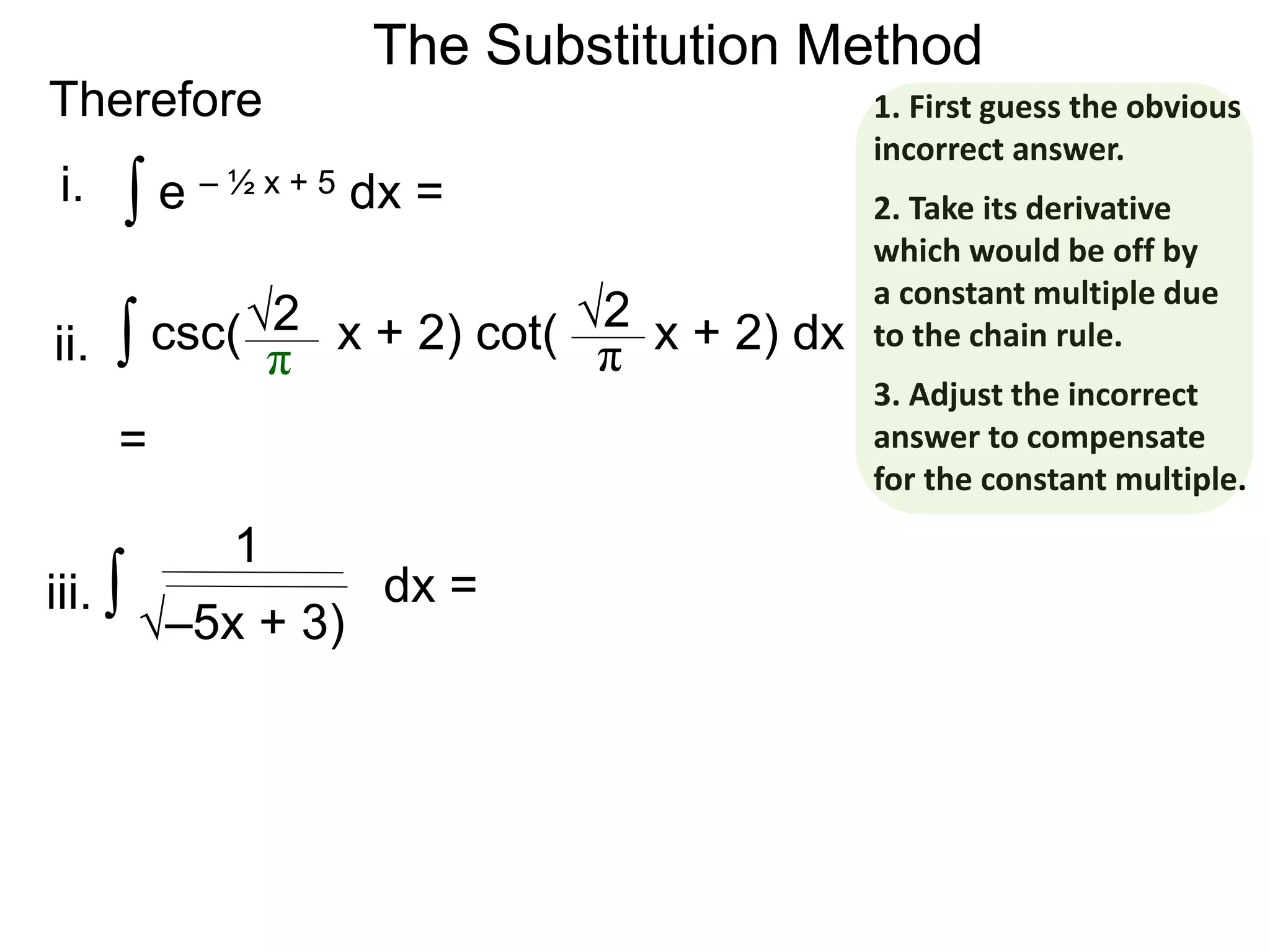

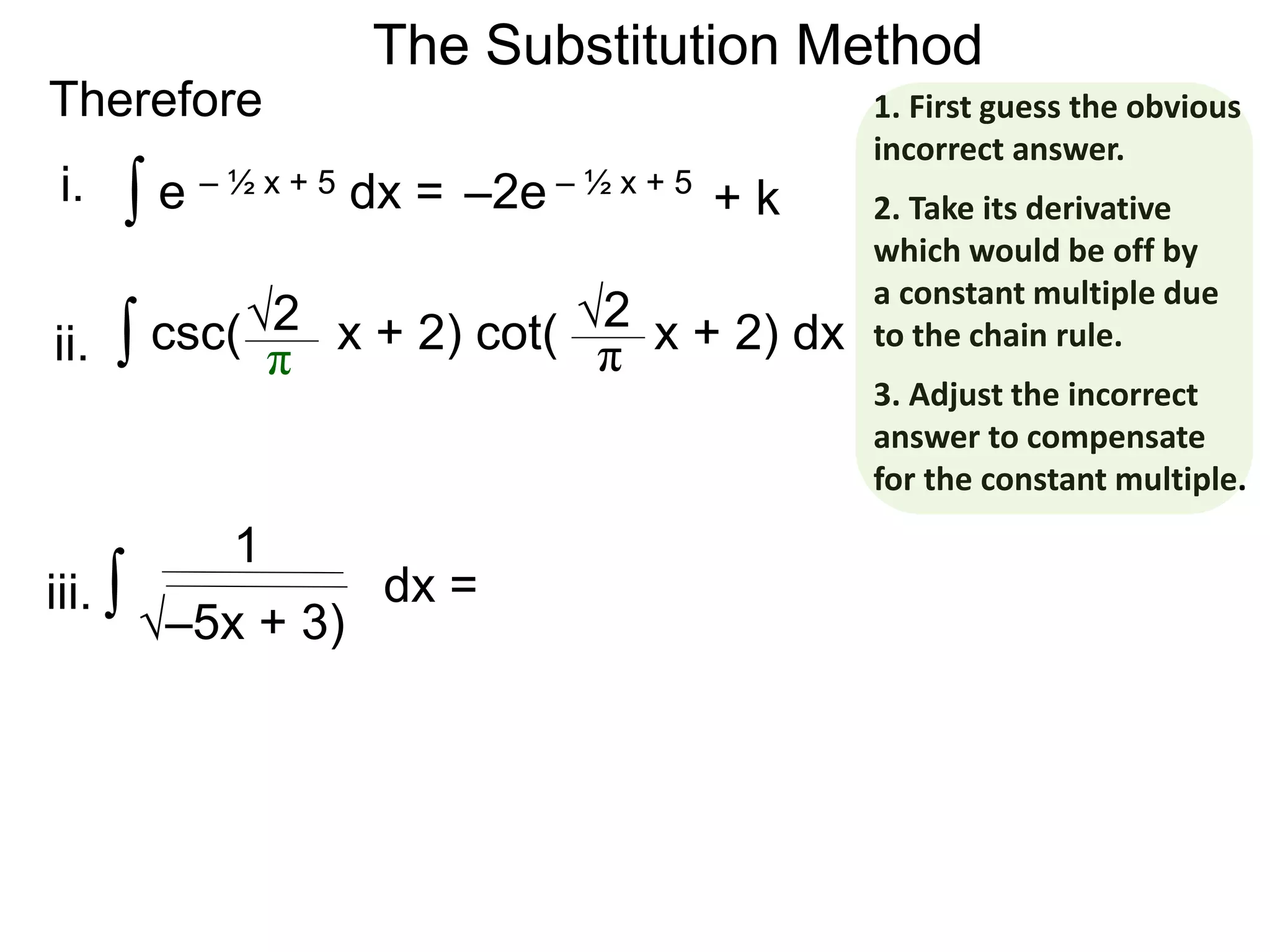

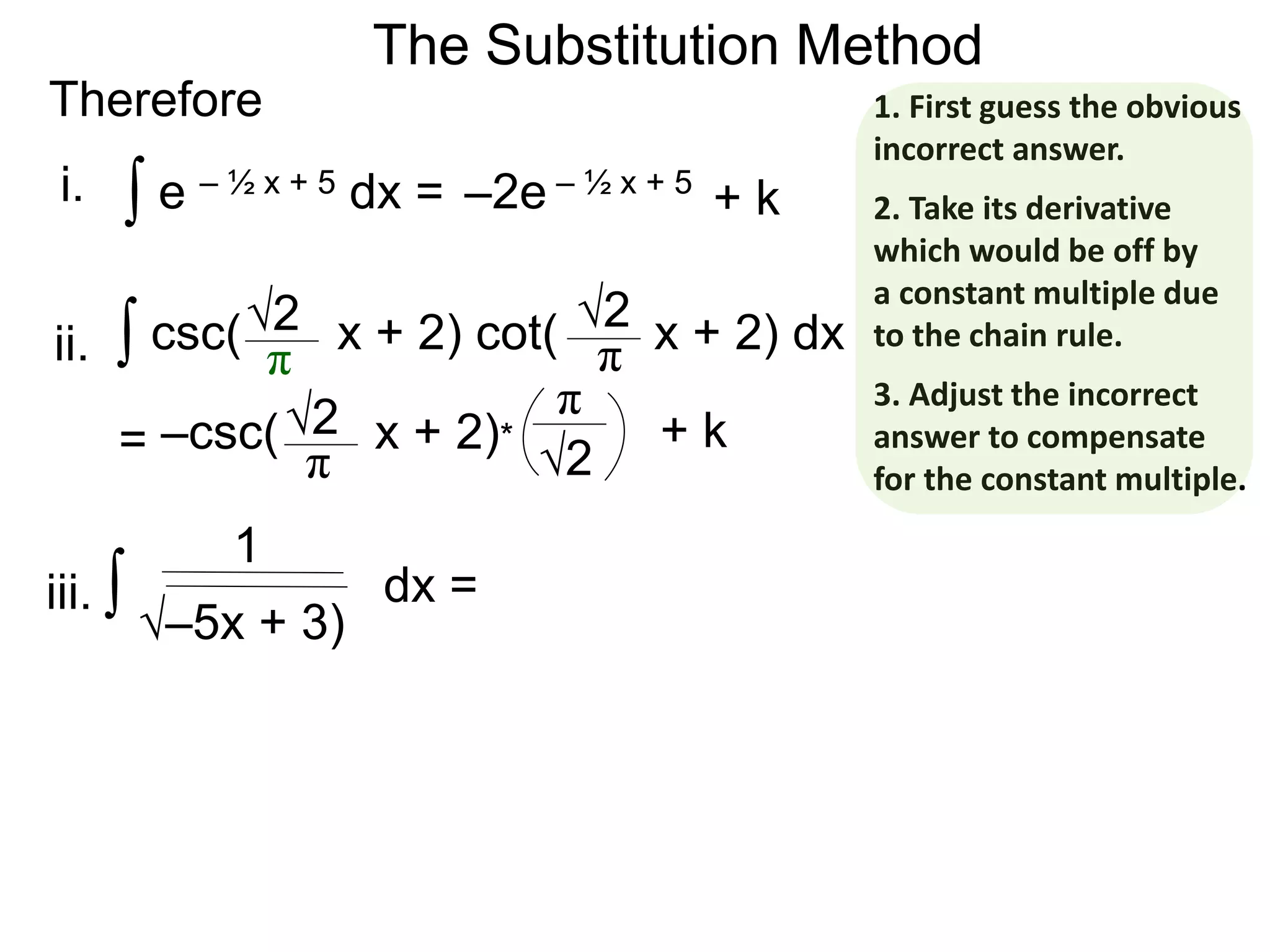

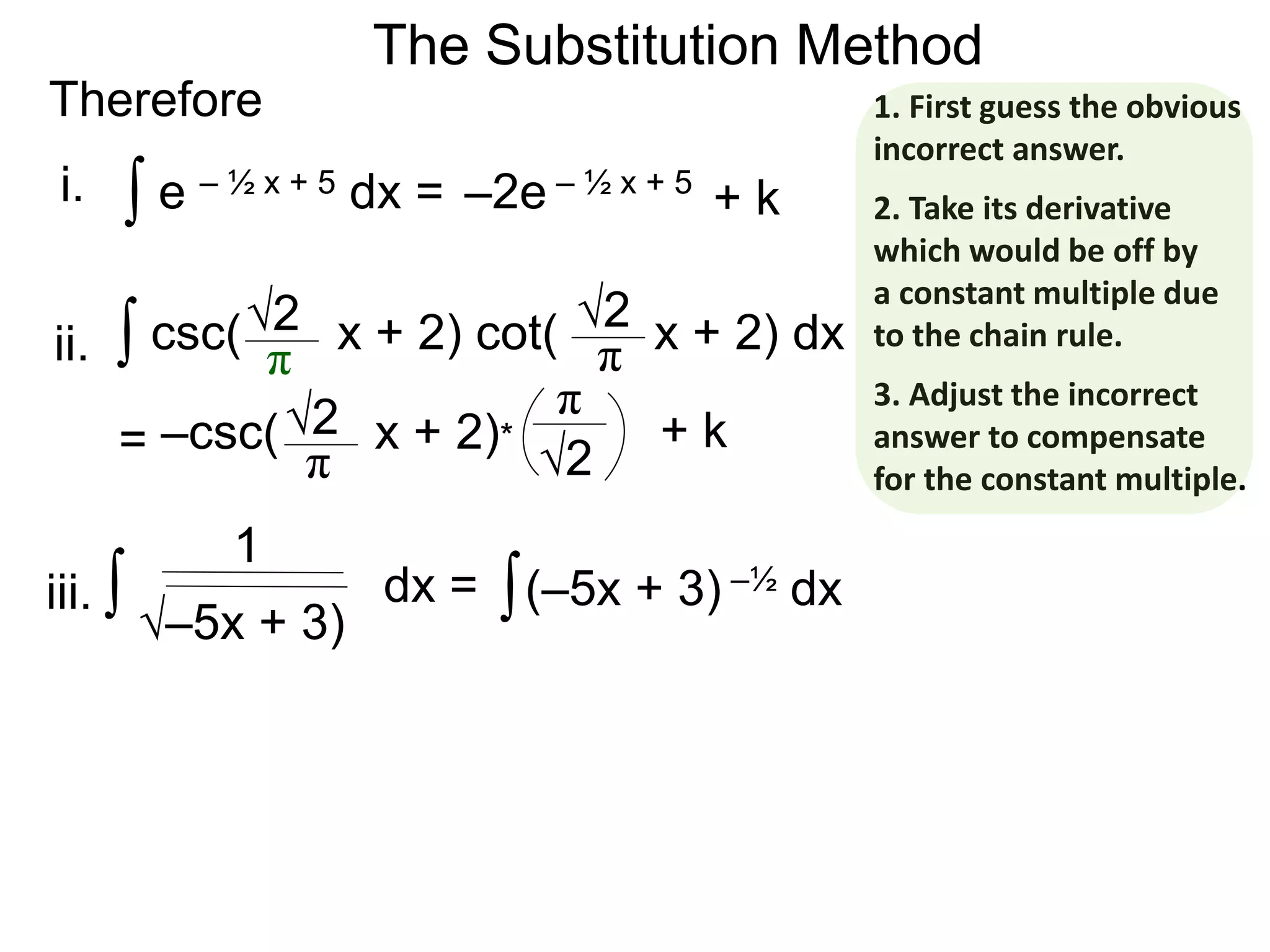

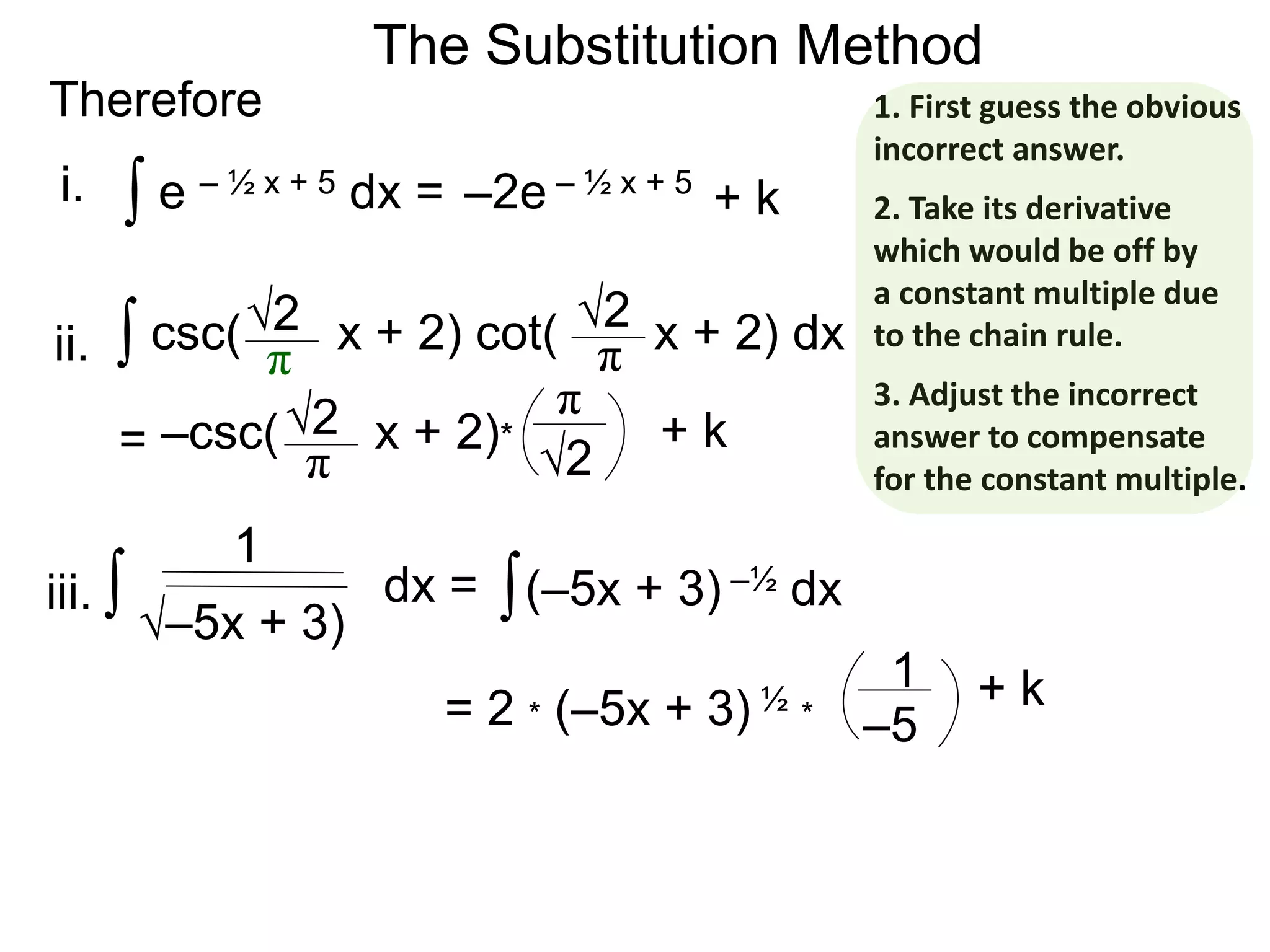

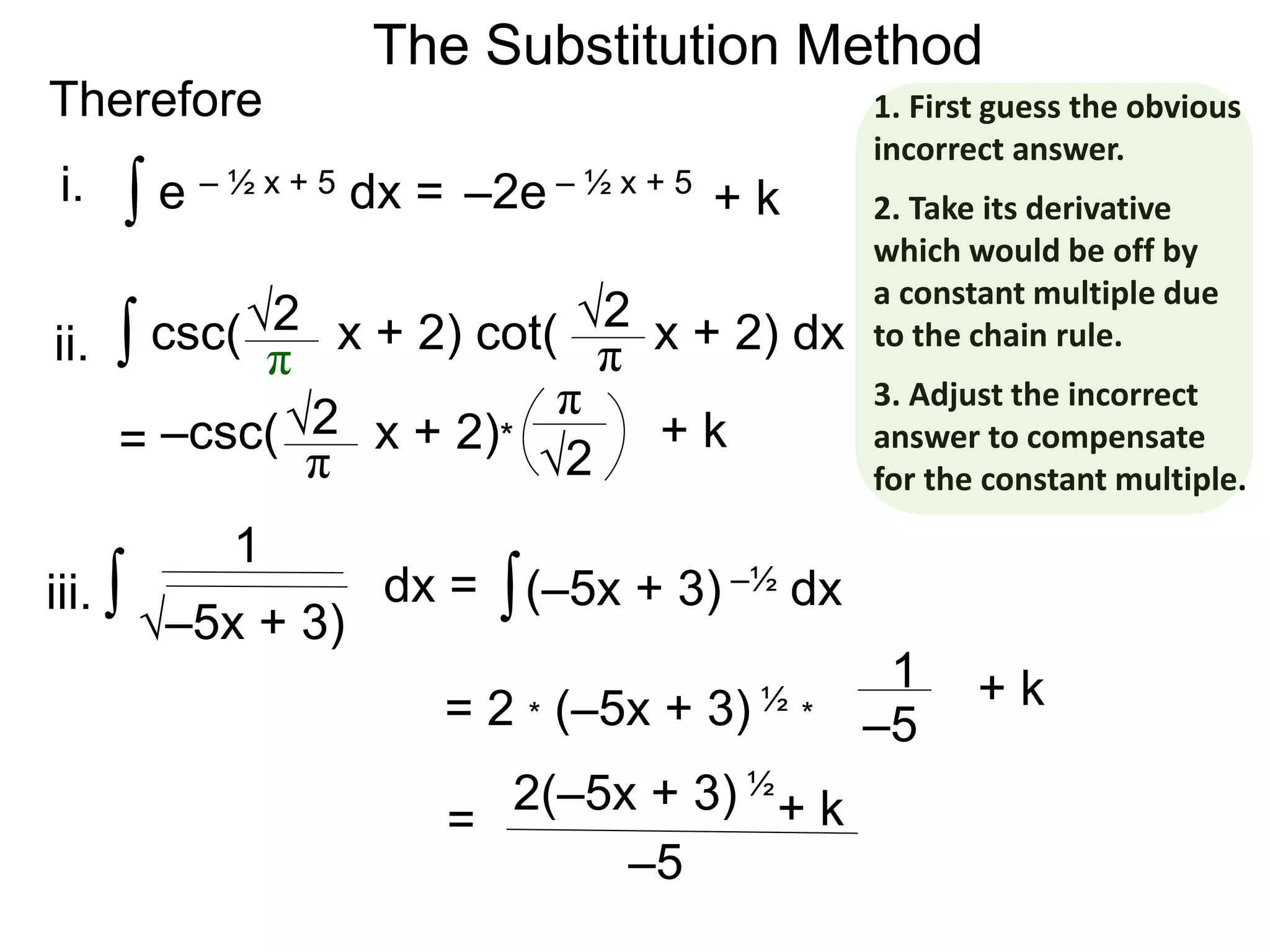

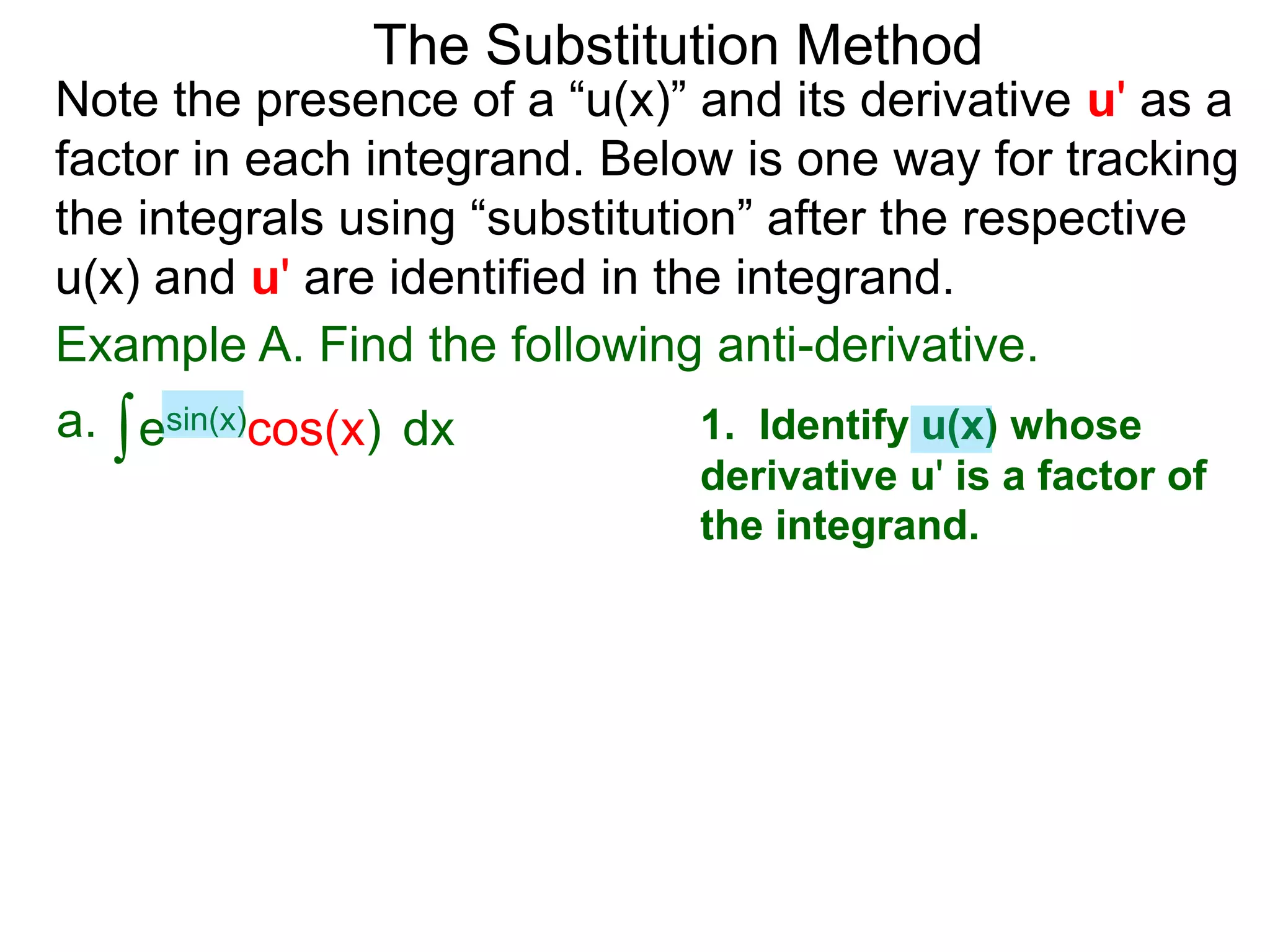

The Substitution Method–Chain Rule Reversed

Let f = f(u) be a function of u, and u = u(x) be a

function x. By the Chain Rule,

the derivative of f with respect to x is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-67-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

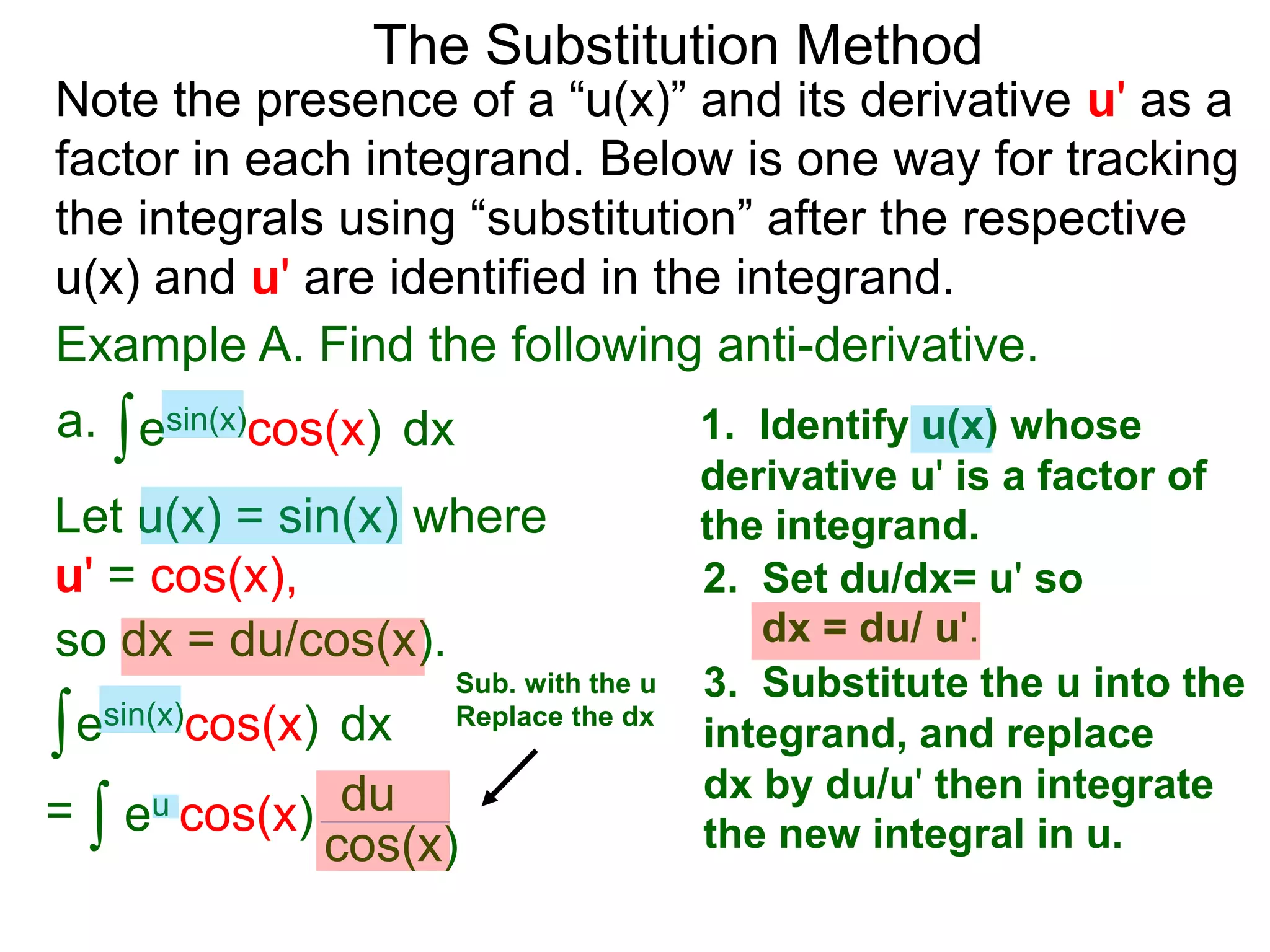

There are two main methods of integration,

the Substitution Method and Integration by Parts.

(f ○ u)'(x) = [f(u(x))]' = f'(u(x))u'(x),

The Substitution Method reverses the Chain Rule

and Integration by Parts unwinds the Product Rule.

The Substitution Method–Chain Rule Reversed

Let f = f(u) be a function of u, and u = u(x) be a

function x. By the Chain Rule,

the derivative of f with respect to x is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-68-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

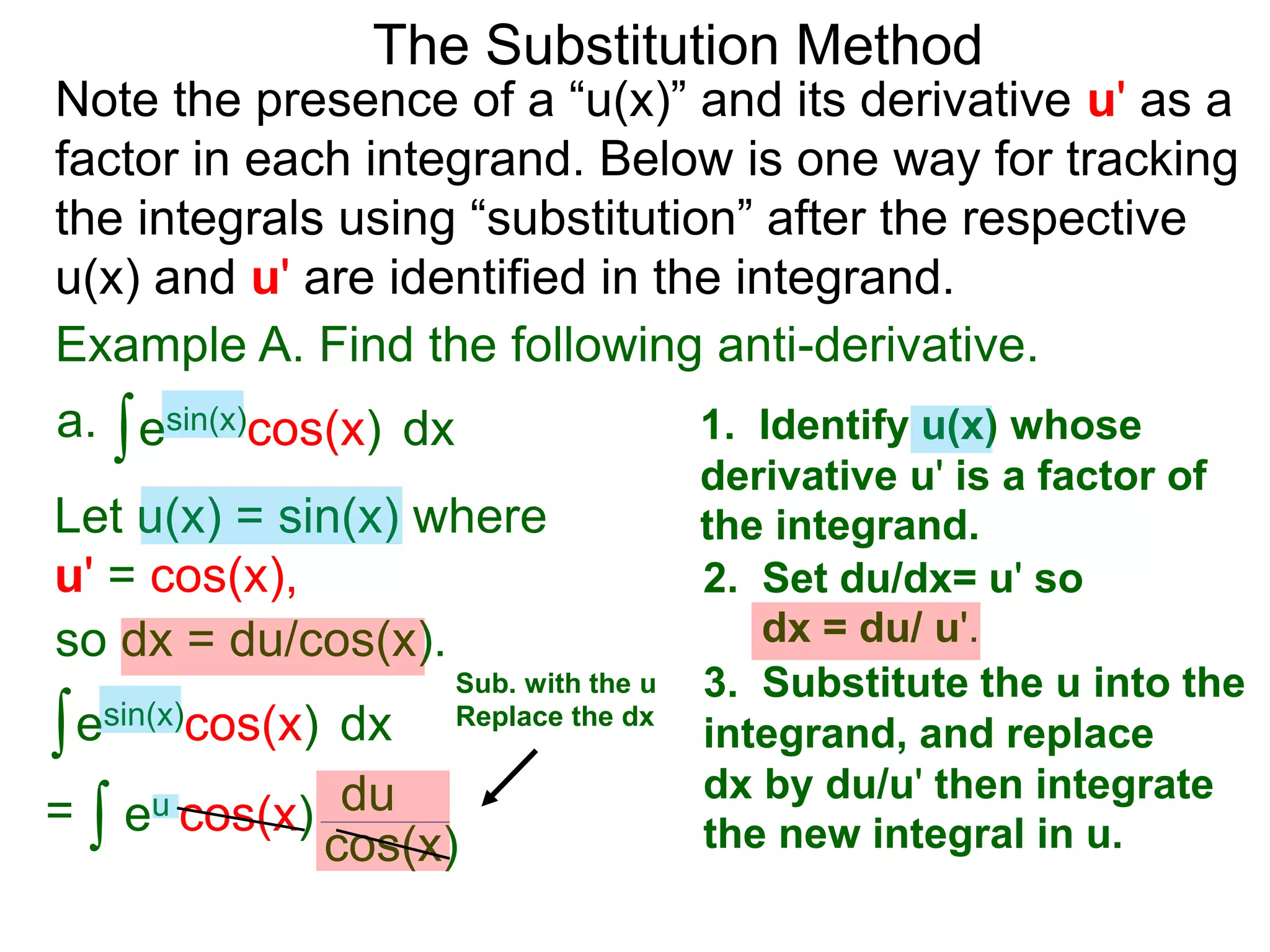

There are two main methods of integration,

the Substitution Method and Integration by Parts.

(f ○ u)'(x) = [f(u(x))]' = f'(u(x))u'(x), or that

The Substitution Method reverses the Chain Rule

and Integration by Parts unwinds the Product Rule.

∫ f'(u(x))u'(x) dx f(u(x)) + k

The Substitution Method–Chain Rule Reversed

Let f = f(u) be a function of u, and u = u(x) be a

function x. By the Chain Rule,

the derivative of f with respect to x is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-69-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

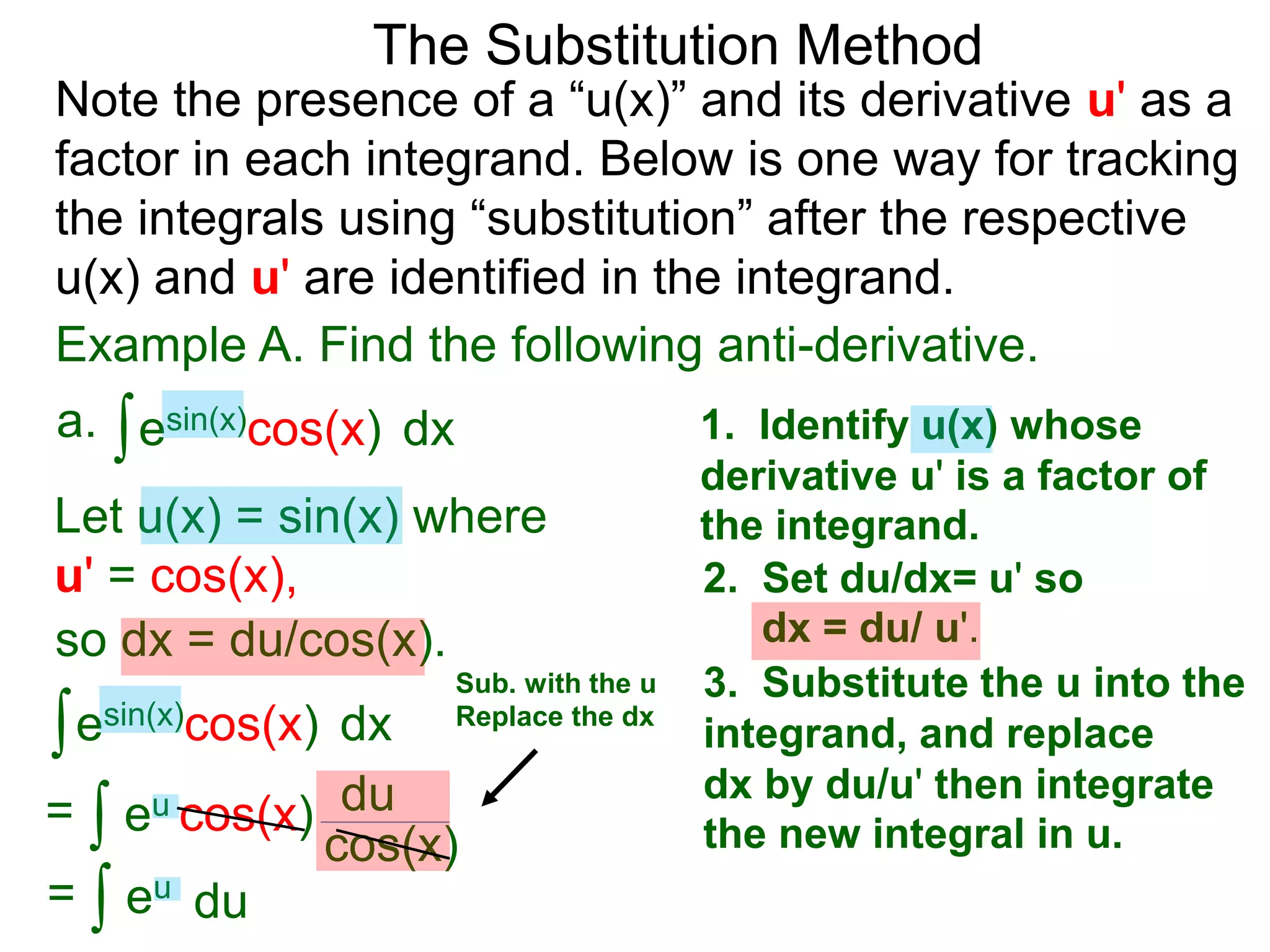

There are two main methods of integration,

the Substitution Method and Integration by Parts.

(f ○ u)'(x) = [f(u(x))]' = f'(u(x))u'(x), or that

The Substitution Method reverses the Chain Rule

and Integration by Parts unwinds the Product Rule.

∫ f'(u(x))u'(x) dx

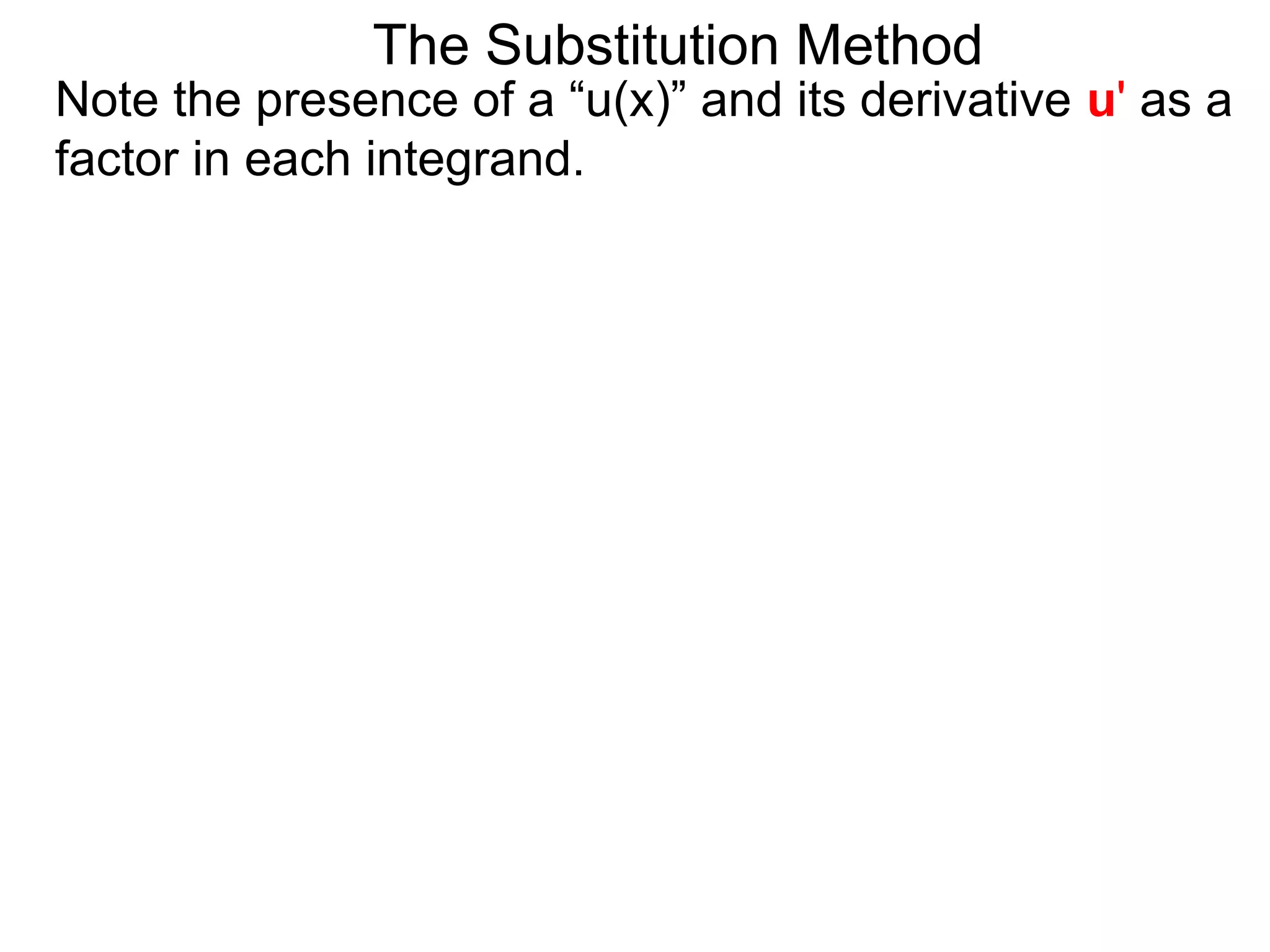

This integration rule is more useful when stated with

f’s as specific basic functions.

f(u(x)) + k

The Substitution Method–Chain Rule Reversed

Let f = f(u) be a function of u, and u = u(x) be a

function x. By the Chain Rule,

the derivative of f with respect to x is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-70-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

There are two main methods of integration,

the Substitution Method and Integration by Parts.

(f ○ u)'(x) = [f(u(x))]' = f'(u(x))u'(x), or that

The Substitution Method reverses the Chain Rule

and Integration by Parts unwinds the Product Rule.

∫ f'(u(x))u'(x) dx

This integration rule is more useful when stated with

f’s as specific basic functions. We list the integral

formulas from last section in their substitution–form .

f(u(x)) + k

The Substitution Method–Chain Rule Reversed

Let f = f(u) be a function of u, and u = u(x) be a

function x. By the Chain Rule,

the derivative of f with respect to x is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-71-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

3

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-104-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-105-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)(3),

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-106-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)(3),

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1

so [ sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)

3

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-107-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)(3),

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1

so [ sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)

3

1

∫ cos(3x + 2) dx =Hence sin(3x + 2)

3

+ k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-108-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)(3),

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1

so [ sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)

3

1

∫ cos(3x + 2) dx =Hence sin(3x + 2)

3

+ k

In fact if F'(x) = f(x), then F'(ax + b) = a*f(ax + b) where

a and b are constants.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-109-2048.jpg)

![The Substitution Method

By the Chain Rule

[sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)(3),

[e3x + 2]' = e3x + 2(3), so [ (e3x + 2)]' = e3x + 2

∫ e3x + 2 dx =Hence

e3x + 2

3 + k

3

1

so [ sin(3x + 2)]' = cos(3x + 2)

3

1

∫ cos(3x + 2) dx =Hence sin(3x + 2)

3

+ k

In fact if F'(x) = f(x), then F'(ax + b) = a*f(ax + b) where

a and b are constants.

∫f(u(x)) dx = F(u(x))a + k where u(x) = ax + b.

(Linear Substitution Integrations) Let F'(x) = f(x),

1then](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2integrationandthesubstitutionmethods-x-190130062728/75/2-integration-and-the-substitution-methods-x-110-2048.jpg)