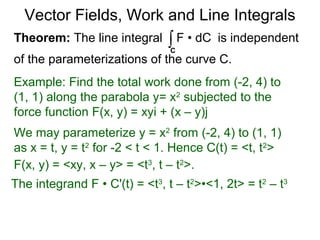

The document discusses the calculation of work done by a force on an object moving along a curve in a vector field. It defines a vector field as a function that assigns a vector to each point in space, representing the force. For a constant force along a straight line, work is calculated as the dot product of the force and displacement vectors. This concept is generalized to calculate work for a varying force along a curved path by partitioning the curve into small line segments, taking the dot product of the force and incremental displacement vectors, and taking the limit as the segment size approaches zero, yielding a line integral formulation for work as the integral of the force dotted with velocity over the curve.

![C(a)=P

C(b)=Q

To find the total work done from

P to Q, we partition the interval

[a, b] by Δt and write the partition

as a=t0, t1, t2,…tn=b.

Vector Fields, Work and Line Integrals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28workandlineintegrals-130513234015-phpapp02/85/28-work-and-line-integrals-29-320.jpg)

![C(a)=P

C(b)=Q

To find the total work done from

P to Q, we partition the interval

[a, b] by Δt and write the partition

as a=t0, t1, t2,…tn=b.

This gives a partition C.

Vector Fields, Work and Line Integrals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28workandlineintegrals-130513234015-phpapp02/85/28-work-and-line-integrals-30-320.jpg)

![C(a)=P

C(b)=Q

C(ti)

To find the total work done from

P to Q, we partition the interval

[a, b] by Δt and write the partition

as a=t0, t1, t2,…tn=b.

This gives a partition C.

Let C(ti) and C(ti +Δt) be a two

points in the partition of C.

C(ti+Δt)

Vector Fields, Work and Line Integrals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28workandlineintegrals-130513234015-phpapp02/85/28-work-and-line-integrals-31-320.jpg)

![C(a)=P

C(b)=Q

C(ti)

F(x(ti), y(ti))

=force at C(ti)

To find the total work done from

P to Q, we partition the interval

[a, b] by Δt and write the partition

as a=t0, t1, t2,…tn=b.

This gives a partition C.

Let C(ti) and C(ti +Δt) be a two

points in the partition of C.

C(ti+Δt)

Then the work required to move the particle from

C(ti) to C(ti+Δt) is approximately the dot product

F(x(ti), y(ti)) • C(ti+Δt) – C(ti)

C(ti+Δt) – C(ti)

Vector Fields, Work and Line Integrals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28workandlineintegrals-130513234015-phpapp02/85/28-work-and-line-integrals-32-320.jpg)

![C(a)=P

C(b)=Q

C(ti)

F(x(ti), y(ti))

=force at C(ti)

To find the total work done from

P to Q, we partition the interval

[a, b] by Δt and write the partition

as a=t0, t1, t2,…tn=b.

This gives a partition C.

Let C(ti) and C(ti +Δt) be a two

points in the partition of C.

C(ti+Δt)

Then the work required to move the particle from

C(ti) to C(ti+Δt) is approximately the dot product

F(x(ti), y(ti)) • C(ti+Δt) – C(ti)

C(ti+Δt) – C(ti)

Hence the total work

W = lim Σ F(x(ti), y(ti)) • C(ti+Δt) – C(ti)Δt0

Vector Fields, Work and Line Integrals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/28workandlineintegrals-130513234015-phpapp02/85/28-work-and-line-integrals-33-320.jpg)