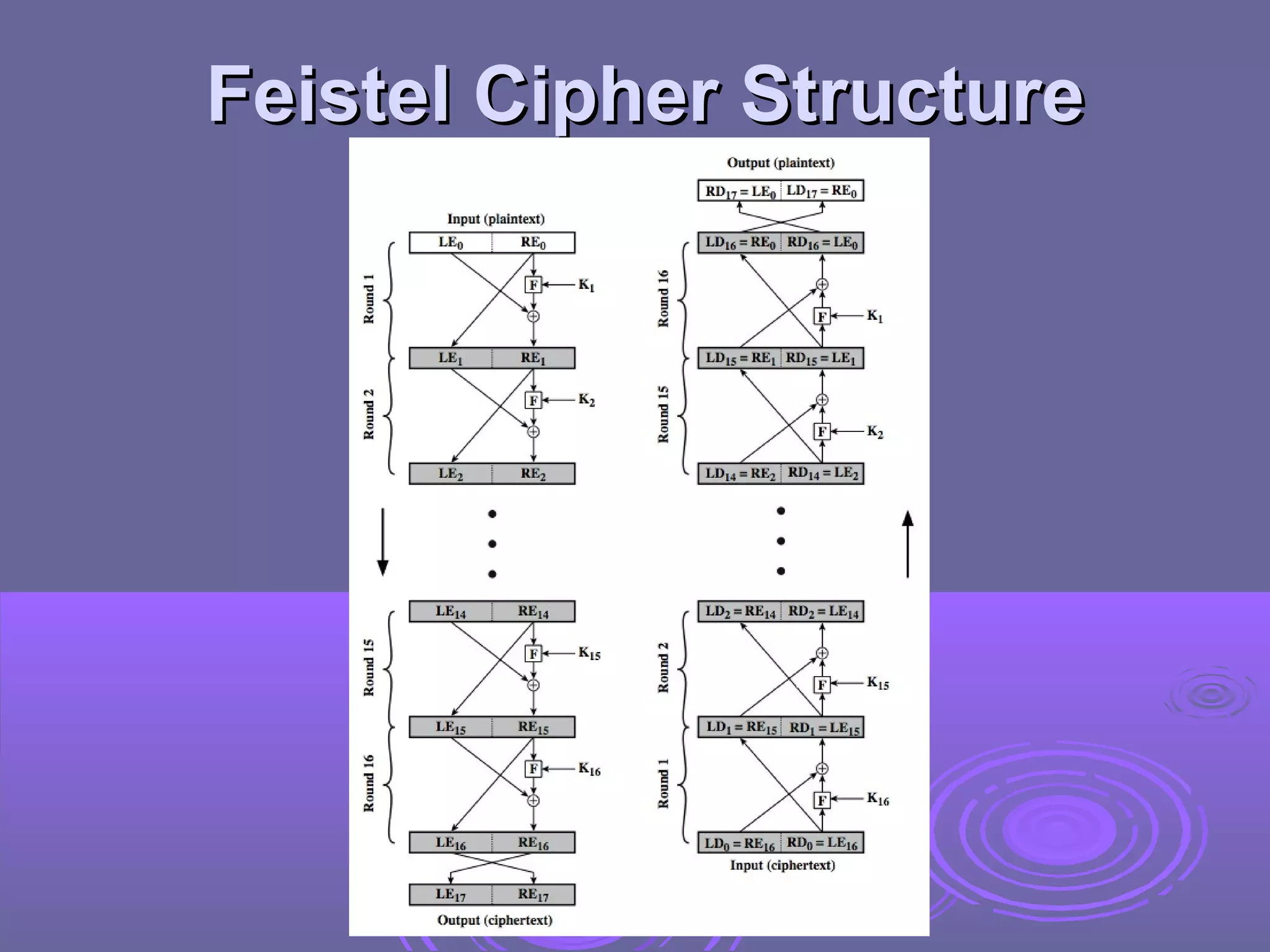

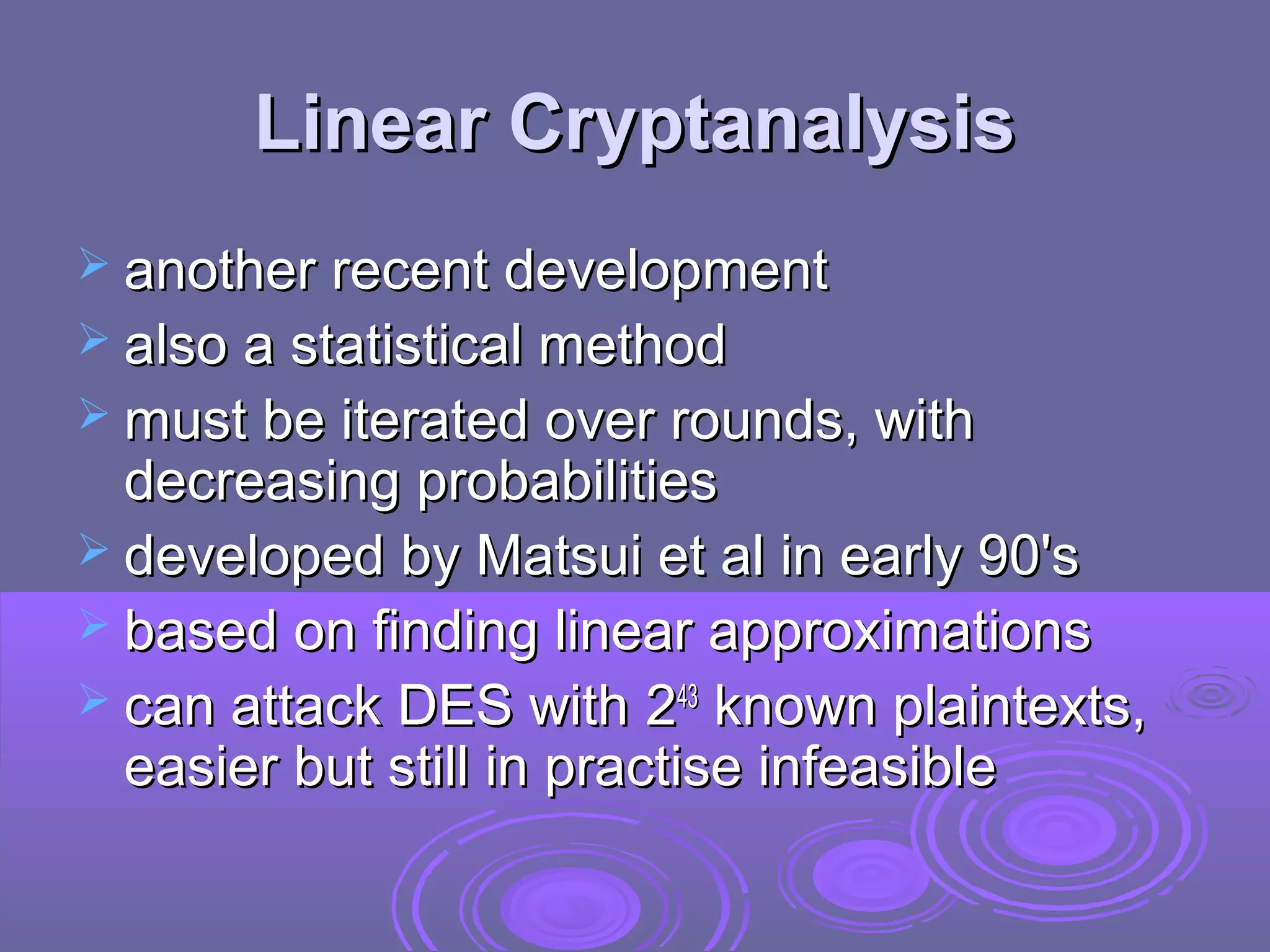

The document discusses block ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard (DES). It begins by explaining the differences between block ciphers and stream ciphers. It then covers the principles of Feistel ciphers and their structure, using DES as a specific example. DES encryption, decryption, and key scheduling are described. The document also discusses attacks on DES like differential and linear cryptanalysis. It concludes by covering modern block cipher design principles.

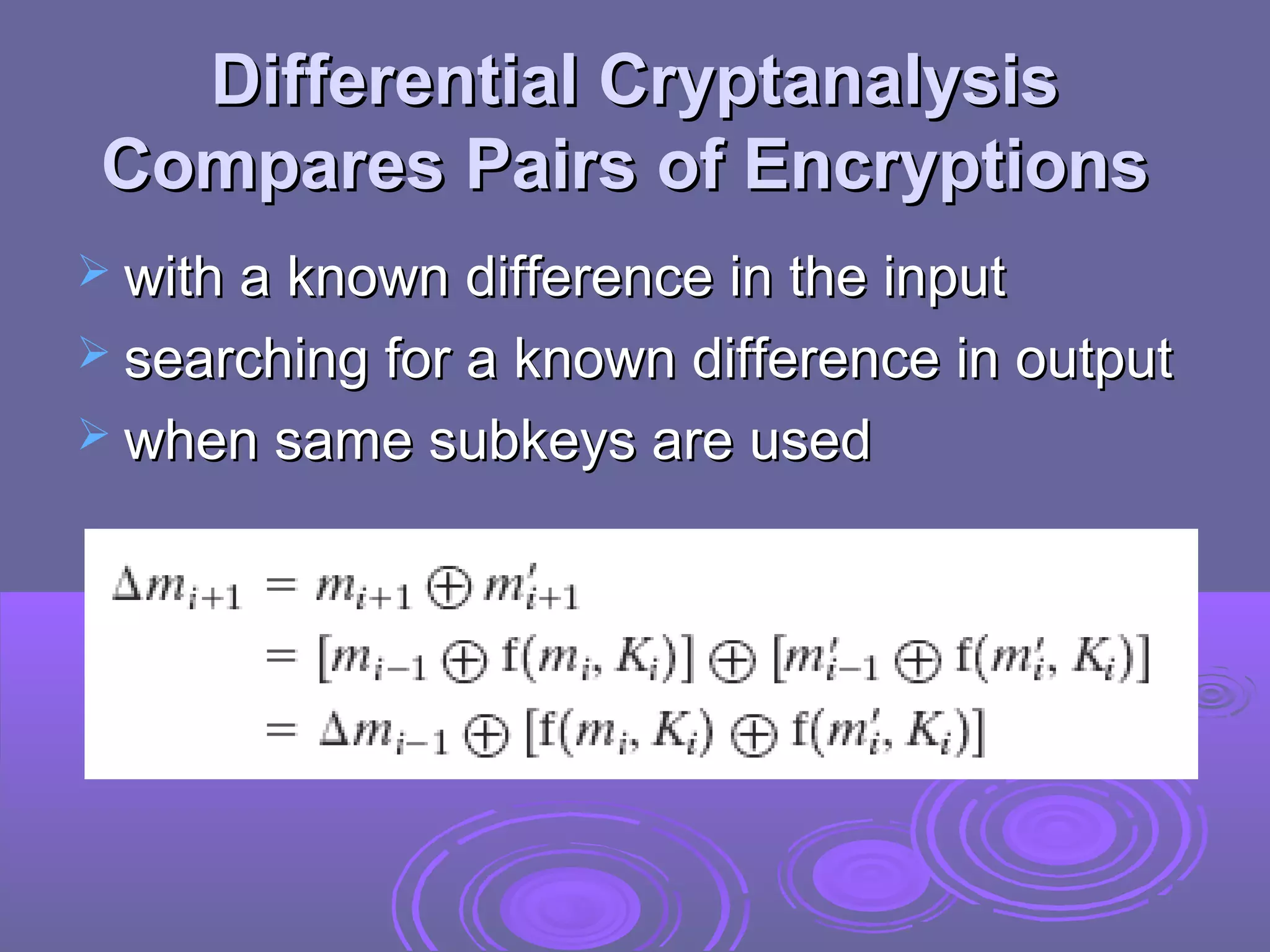

![Linear Cryptanalysis

find linear approximations with prob p != ½

P[i1,i2,...,ia] ⊕ C[j1,j2,...,jb] =

K[k1,k2,...,kc]

where ia,jb,kc are bit locations in P,C,K

gives linear equation for key bits

get one key bit using max likelihood alg

using a large number of trial encryptions

effectiveness given by:

|p–1/2|](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/11848ch03-140102041134-phpapp02/75/cryptography-and-network-security-chap-3-36-2048.jpg)

![DES Design Criteria

as reported by Coppersmith in [COPP94]

7 criteria for S-boxes provide for

non-linearity

resistance to differential cryptanalysis

good confusion

3 criteria for permutation P provide for

increased diffusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/11848ch03-140102041134-phpapp02/75/cryptography-and-network-security-chap-3-37-2048.jpg)