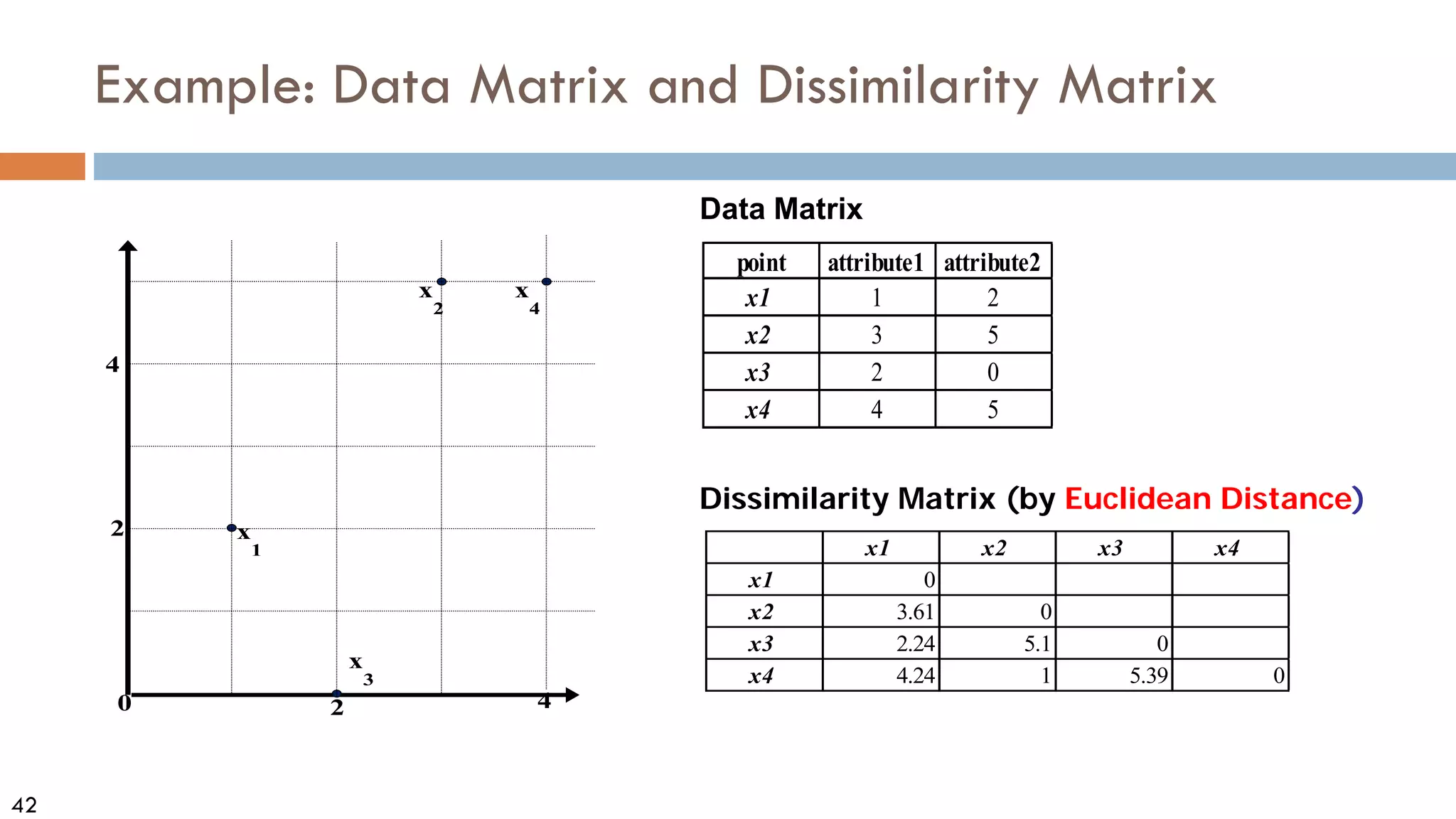

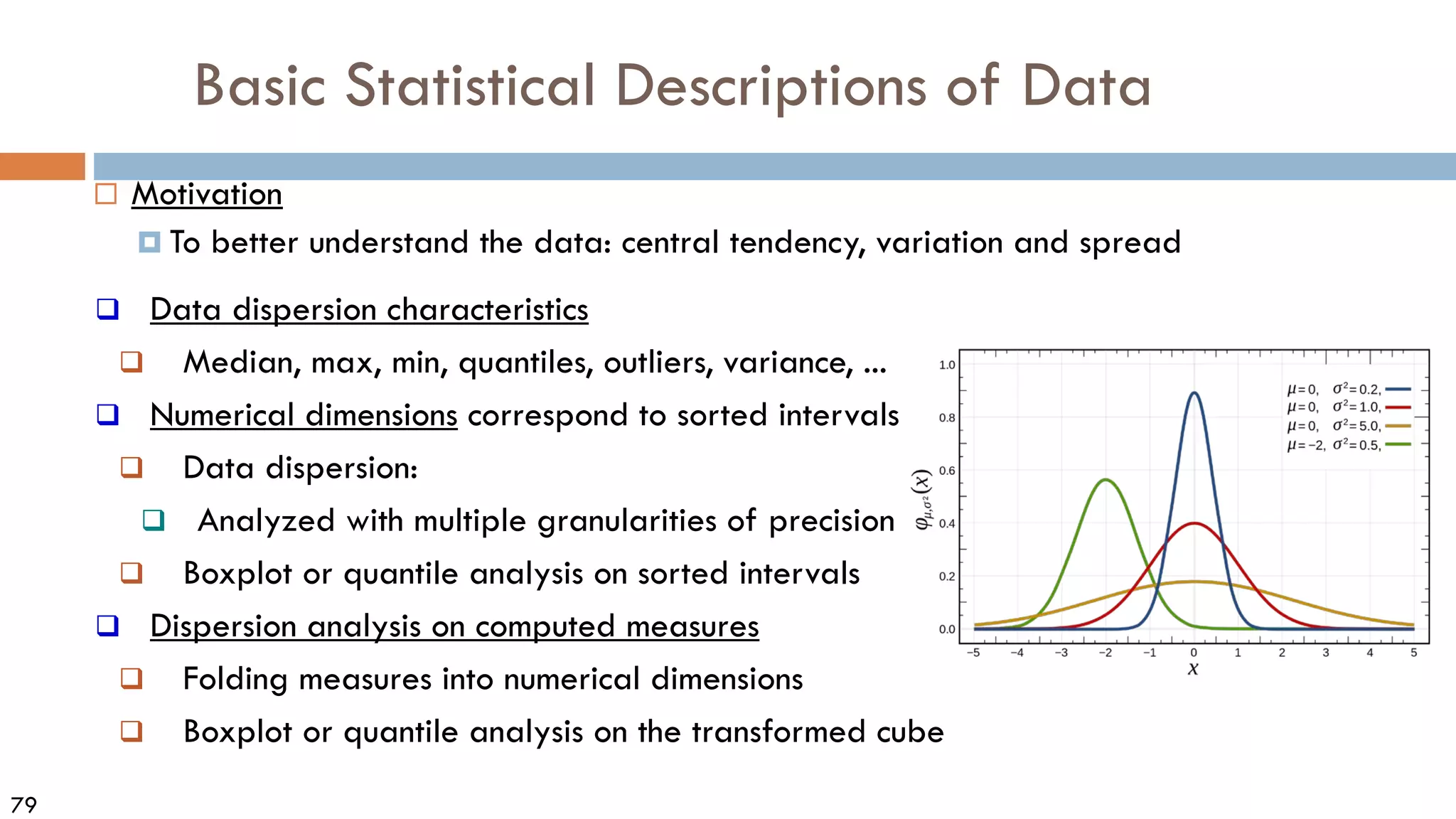

This document discusses data and data preprocessing in data mining. It defines what data is, including data objects and attributes. It describes different attribute types like nominal, binary, ordinal, interval-scaled and ratio-scaled numeric attributes. It also discusses measuring the central tendency of data using the mean, median and mode. Additionally, it covers measuring data distribution through variance, standard deviation and z-scores. Finally, it briefly introduces measuring data similarity and dissimilarity, as well as an overview of data preprocessing.

![33

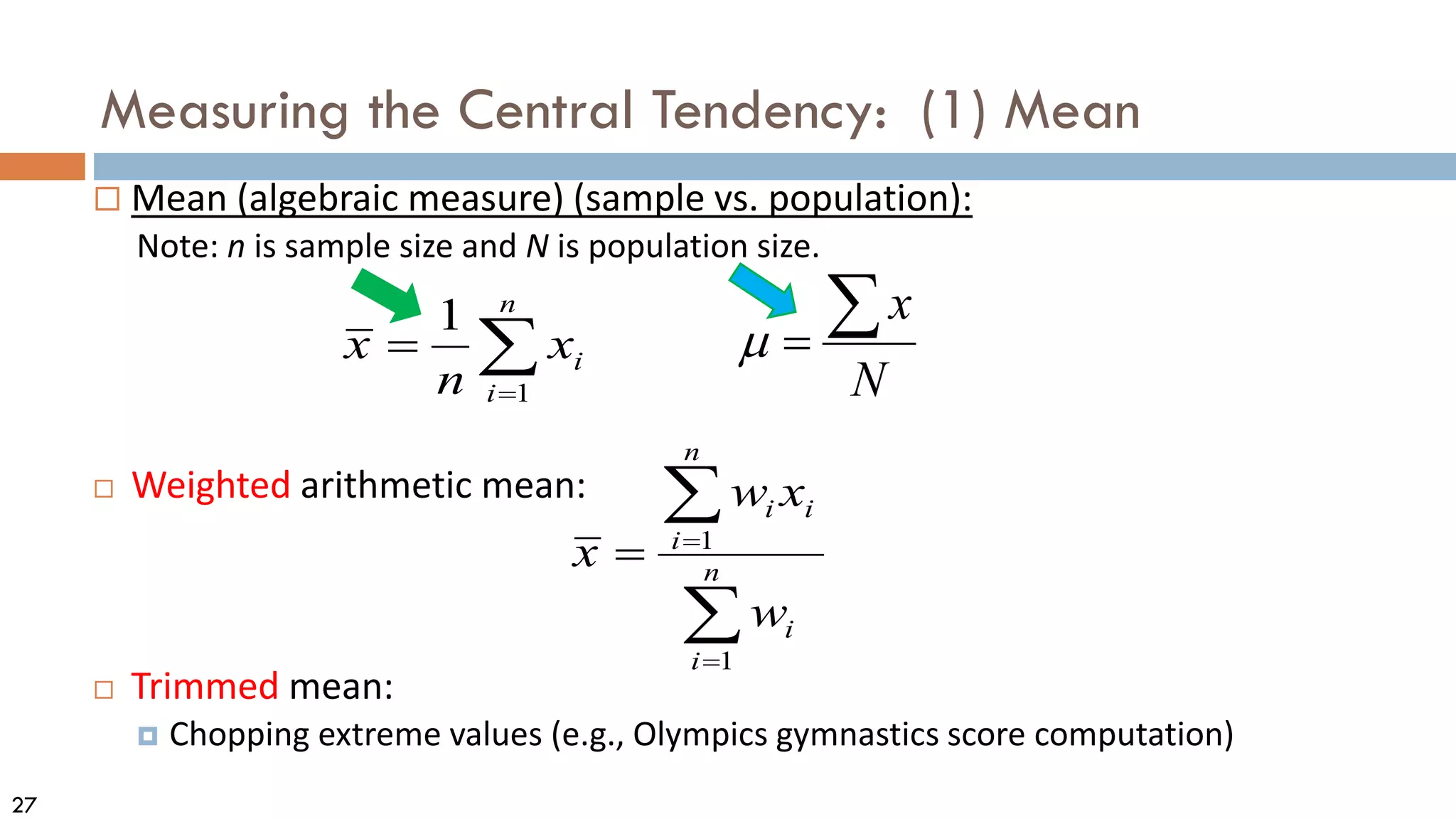

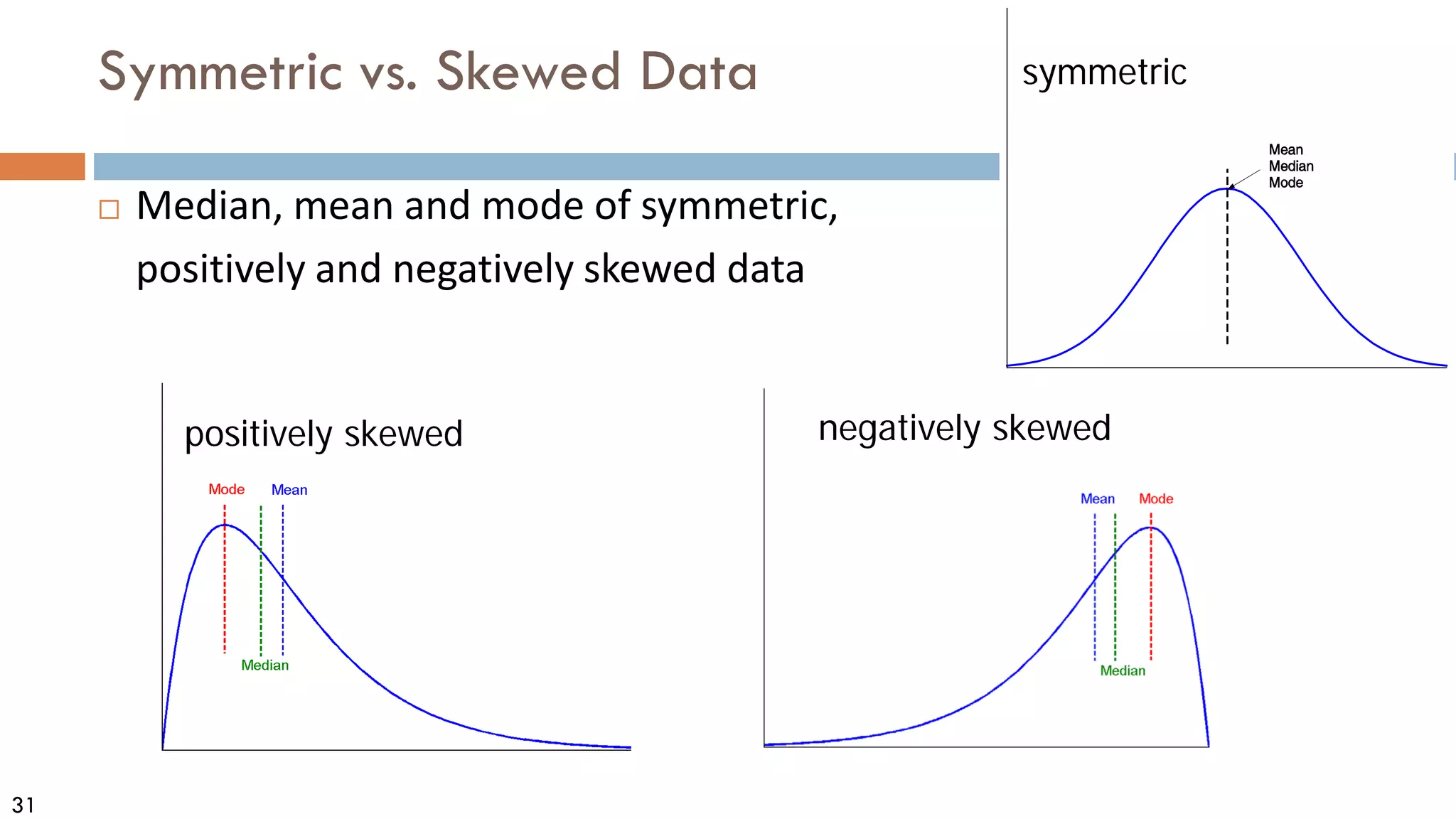

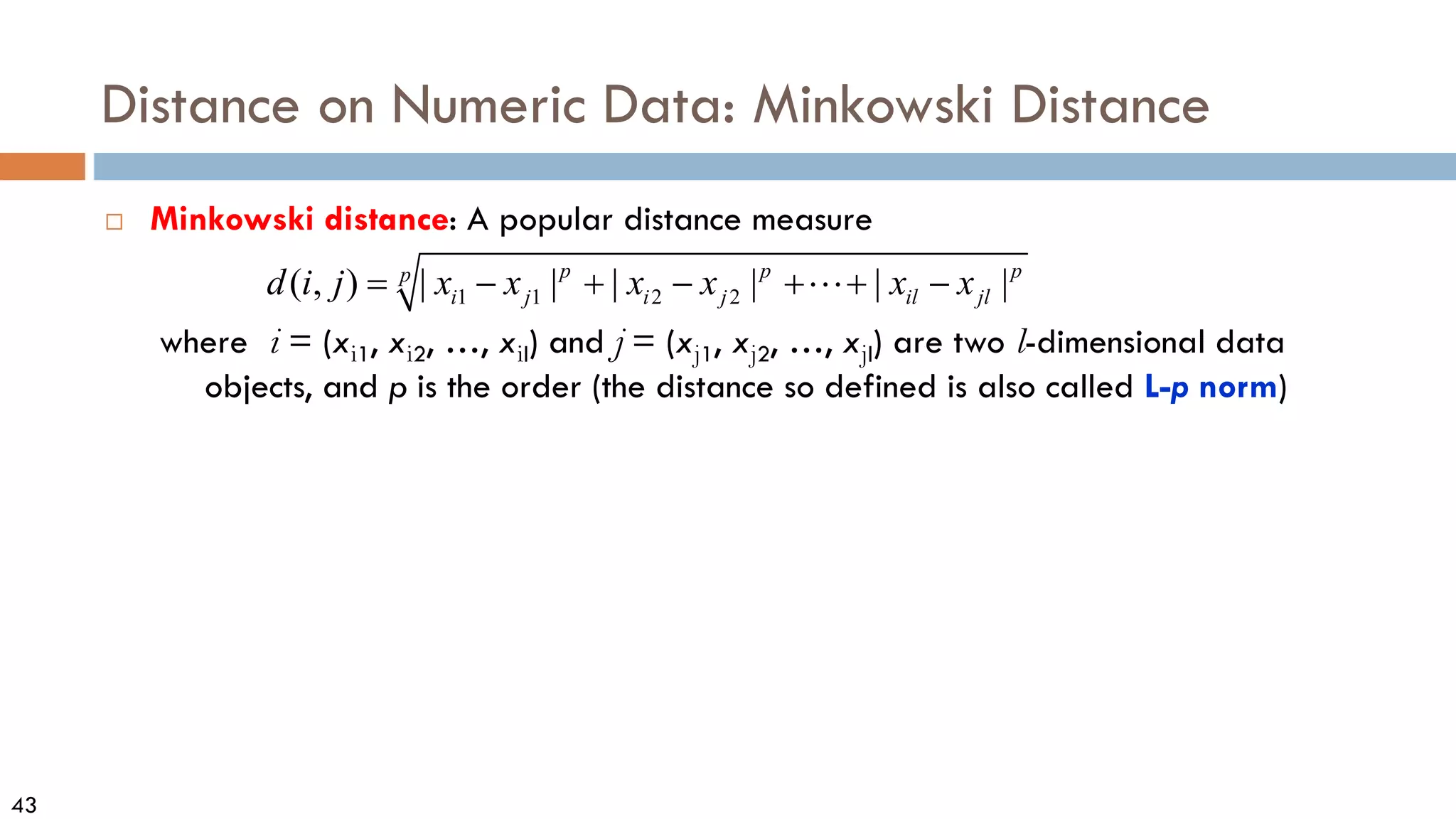

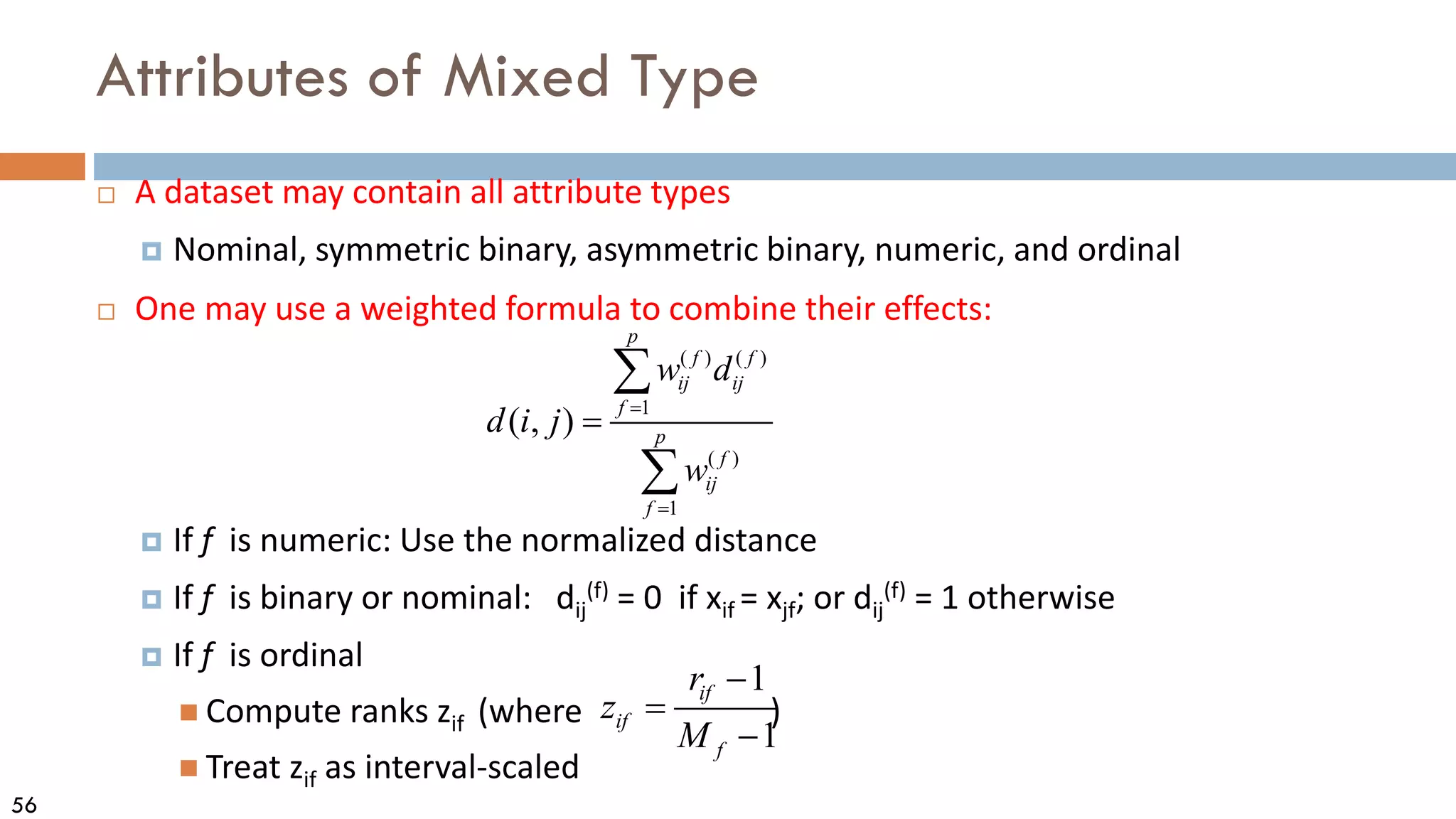

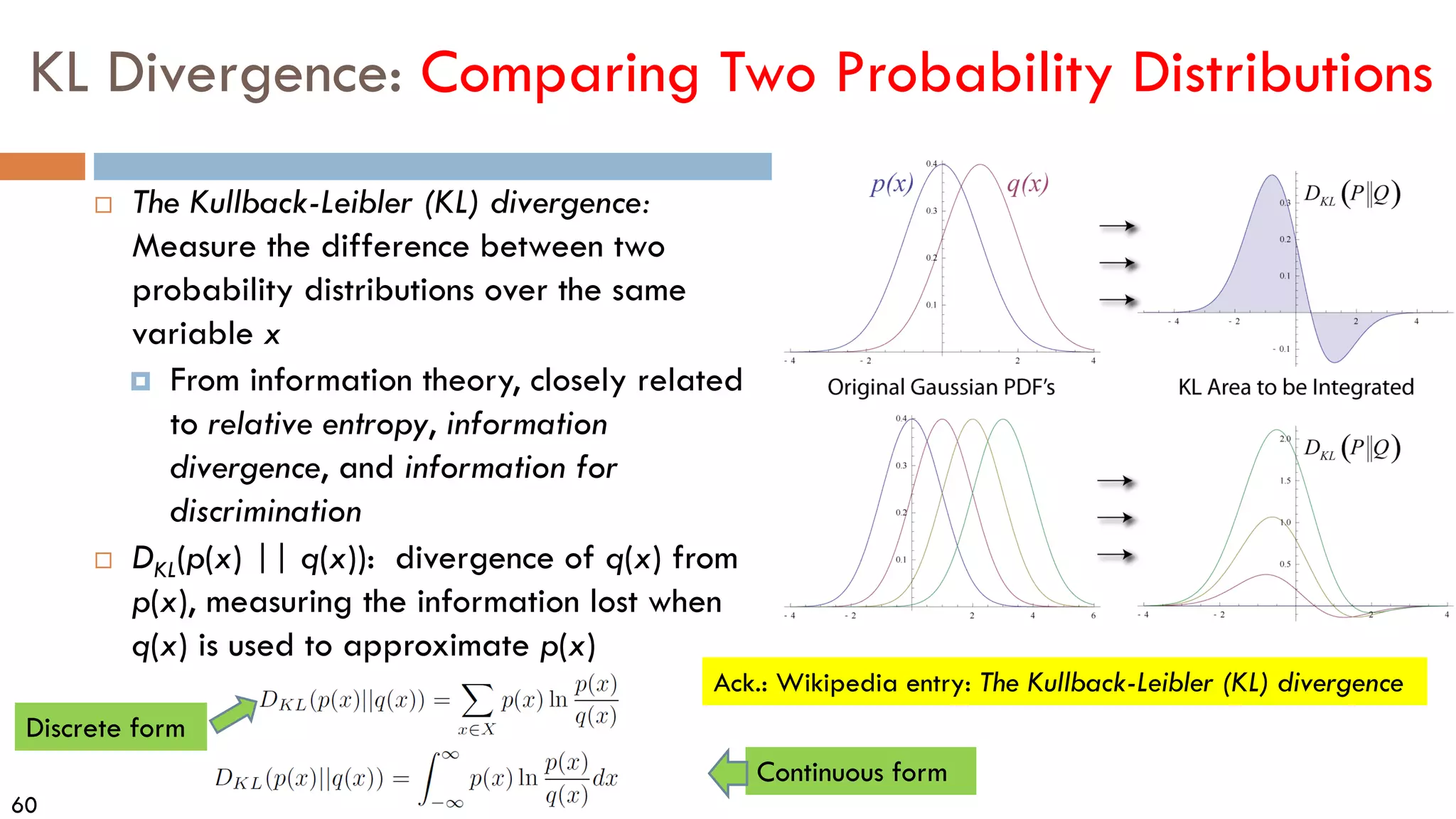

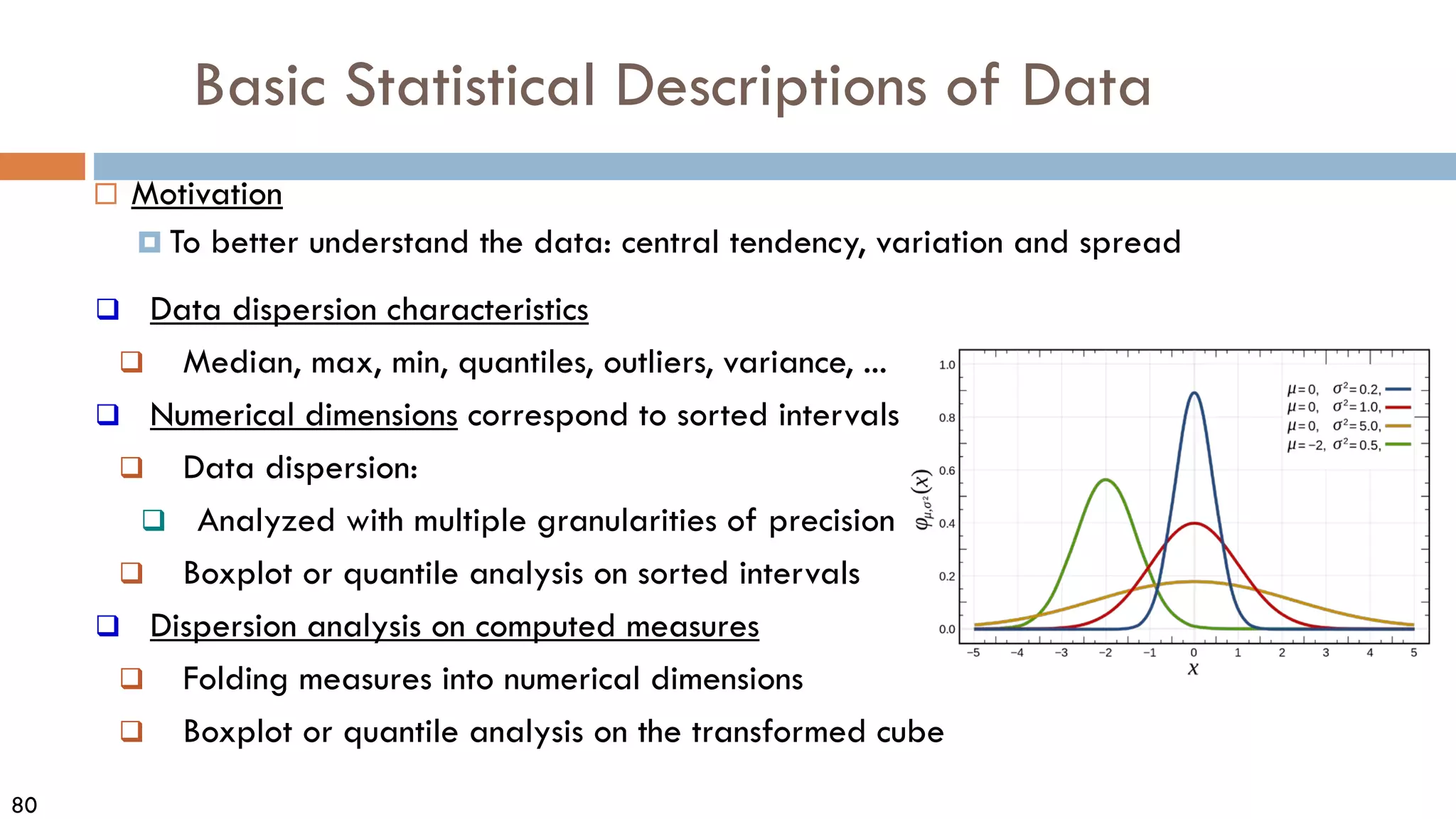

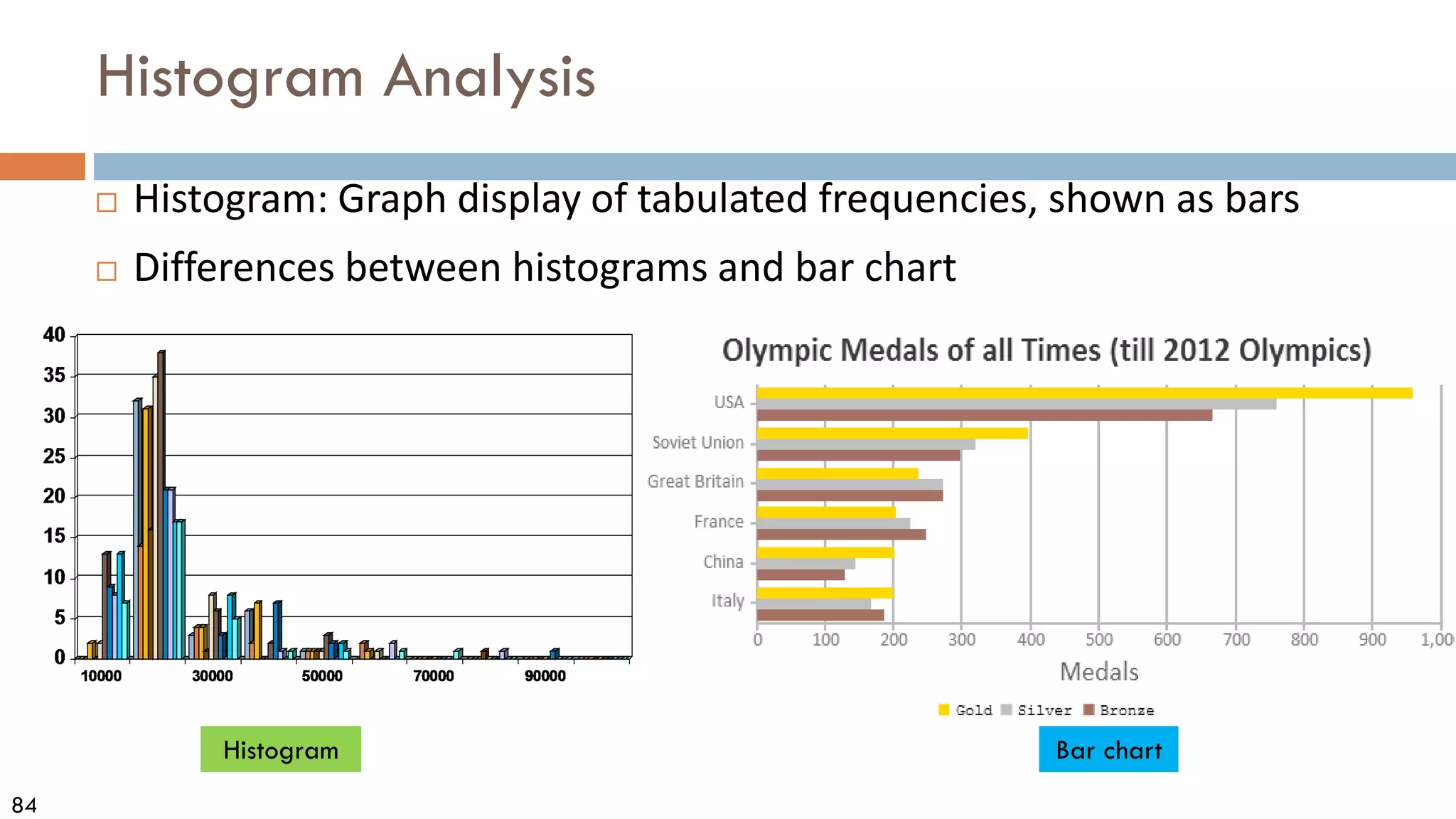

Measures Data Distribution: Variance and Standard Deviation

Variance and standard deviation (sample: s, population: σ)

Variance: (algebraic, scalable computation)

Standard deviation s (or σ) is the square root of variance s2 (orσ2 )

∑

∑ =

=

−

=

−

=

n

i

i

n

i

i x

N

x

N 1

2

2

1

2

2 1

)

(

1

µ

µ

σ

∑ ∑

∑ = =

=

−

−

=

−

−

=

n

i

n

i

i

i

n

i

i x

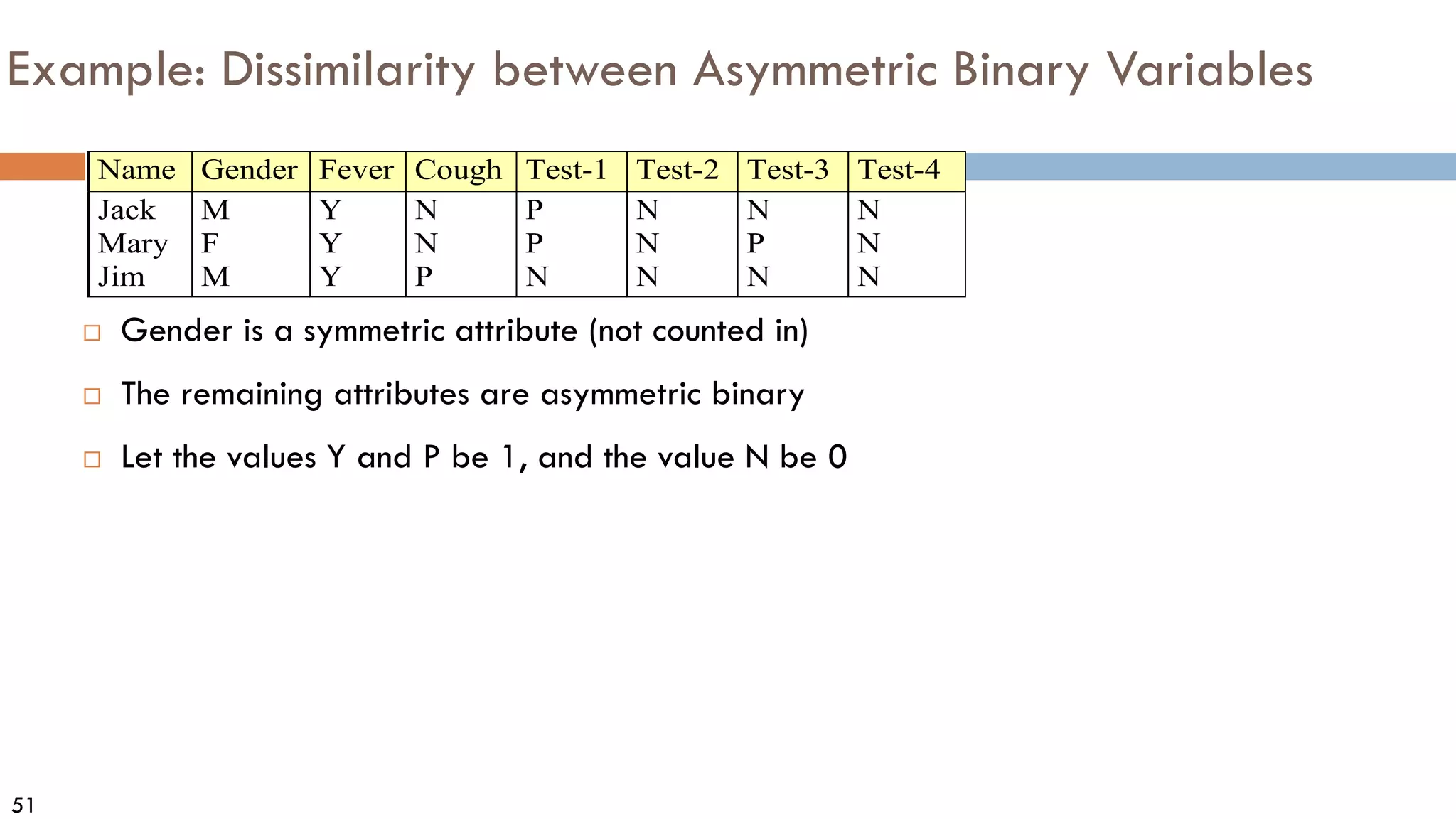

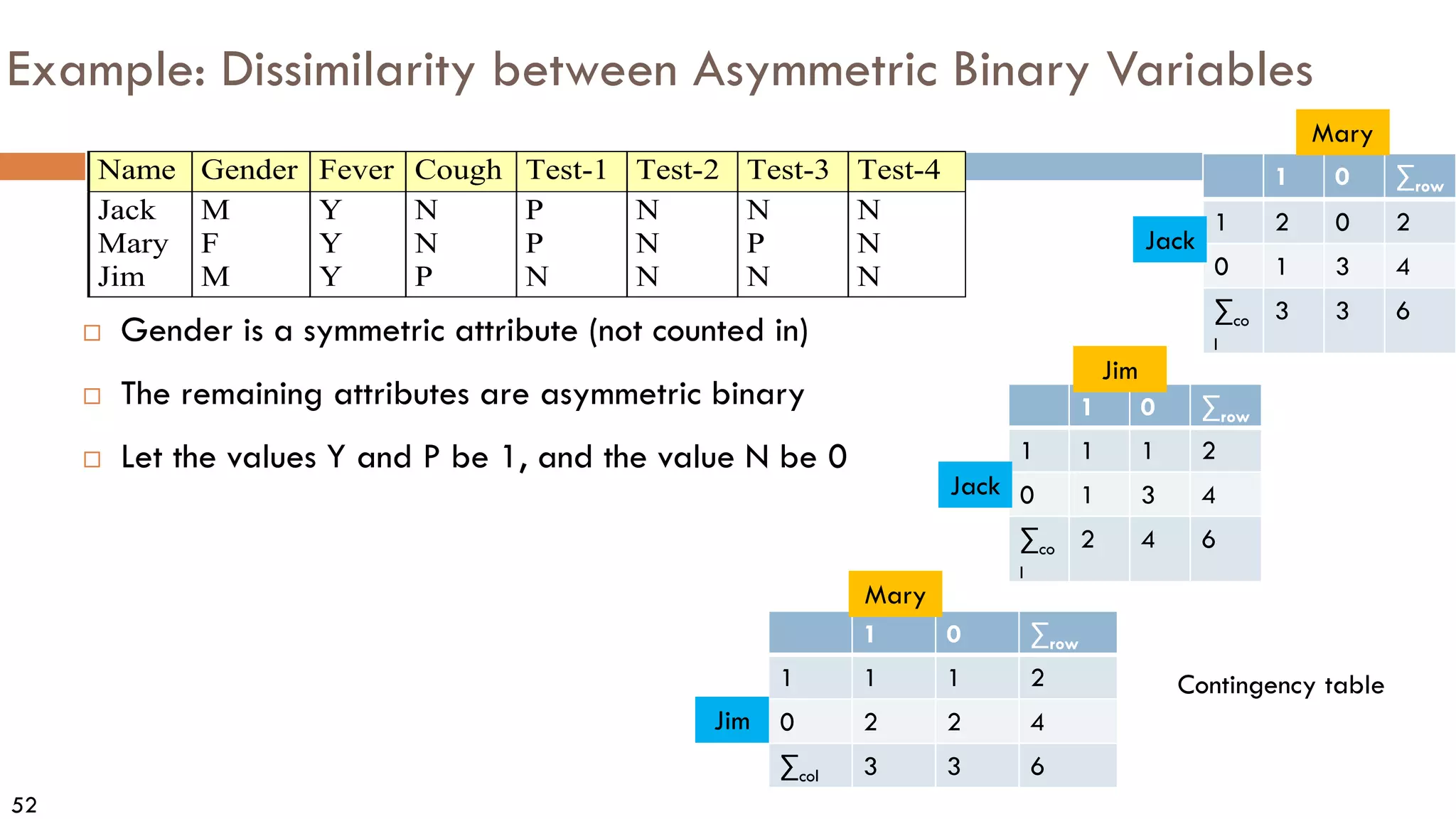

n

x

n

x

x

n

s

1 1

2

2

1

2

2

]

)

(

1

[

1

1

)

(

1

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-33-2048.jpg)

![34

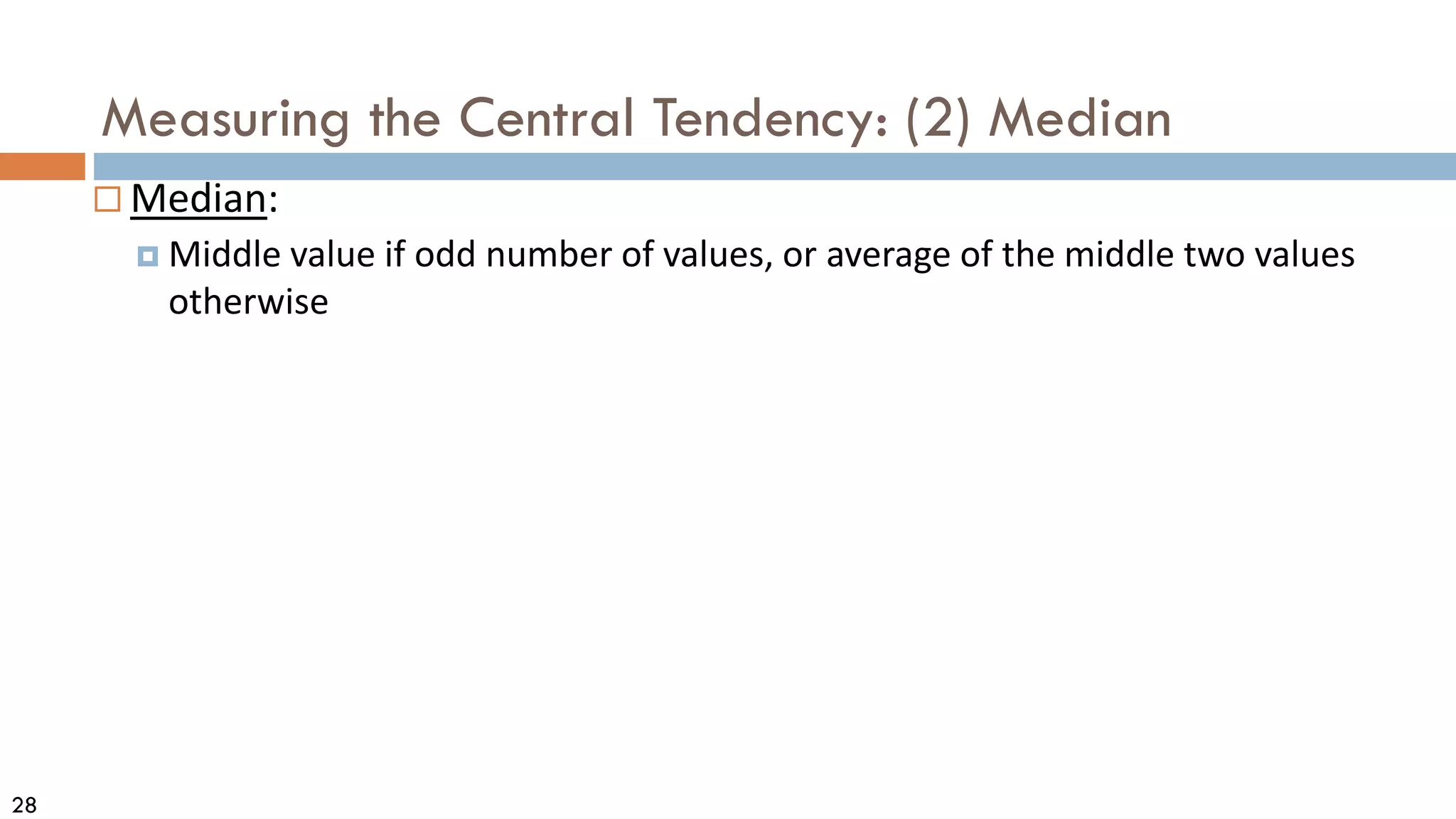

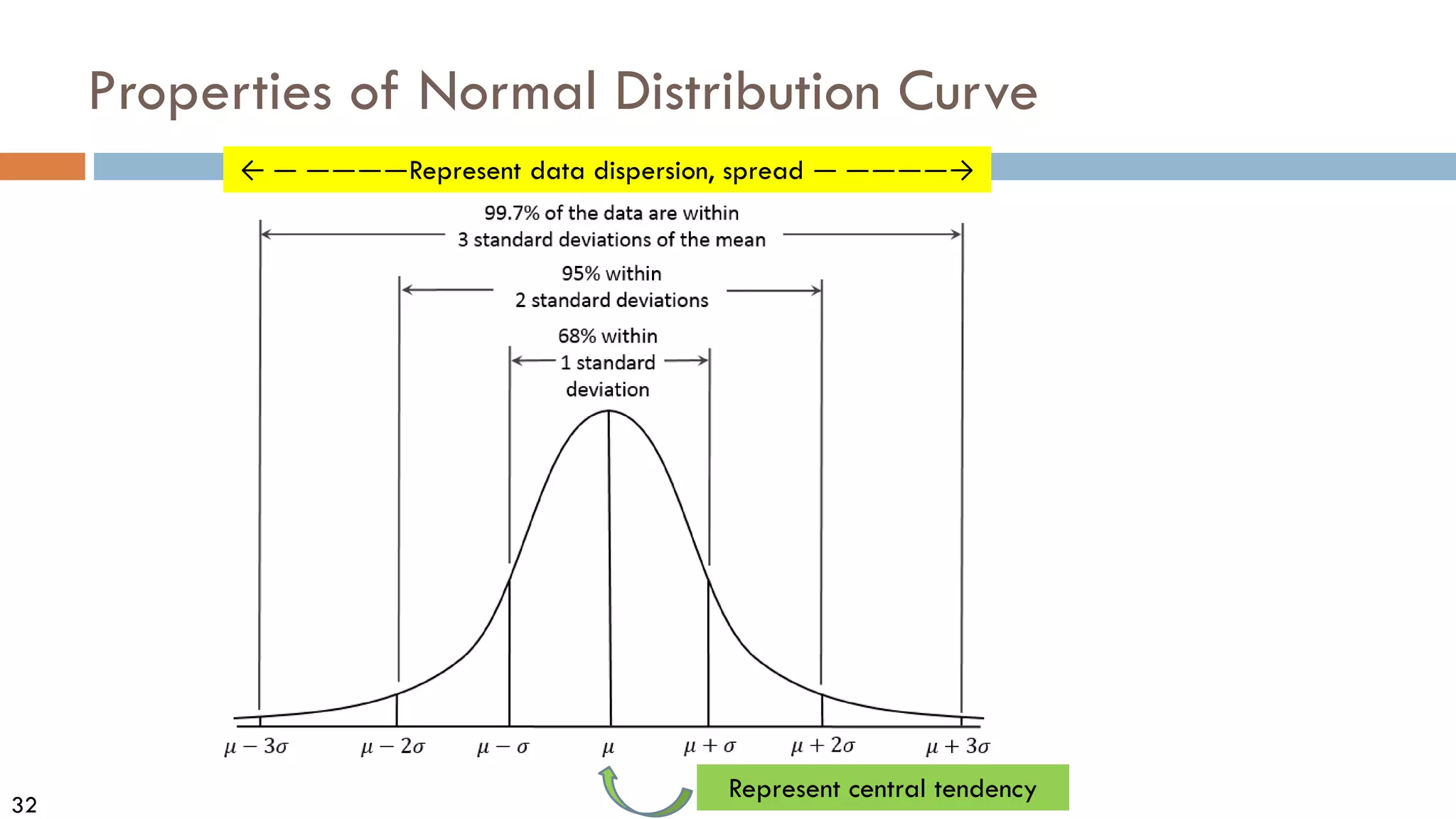

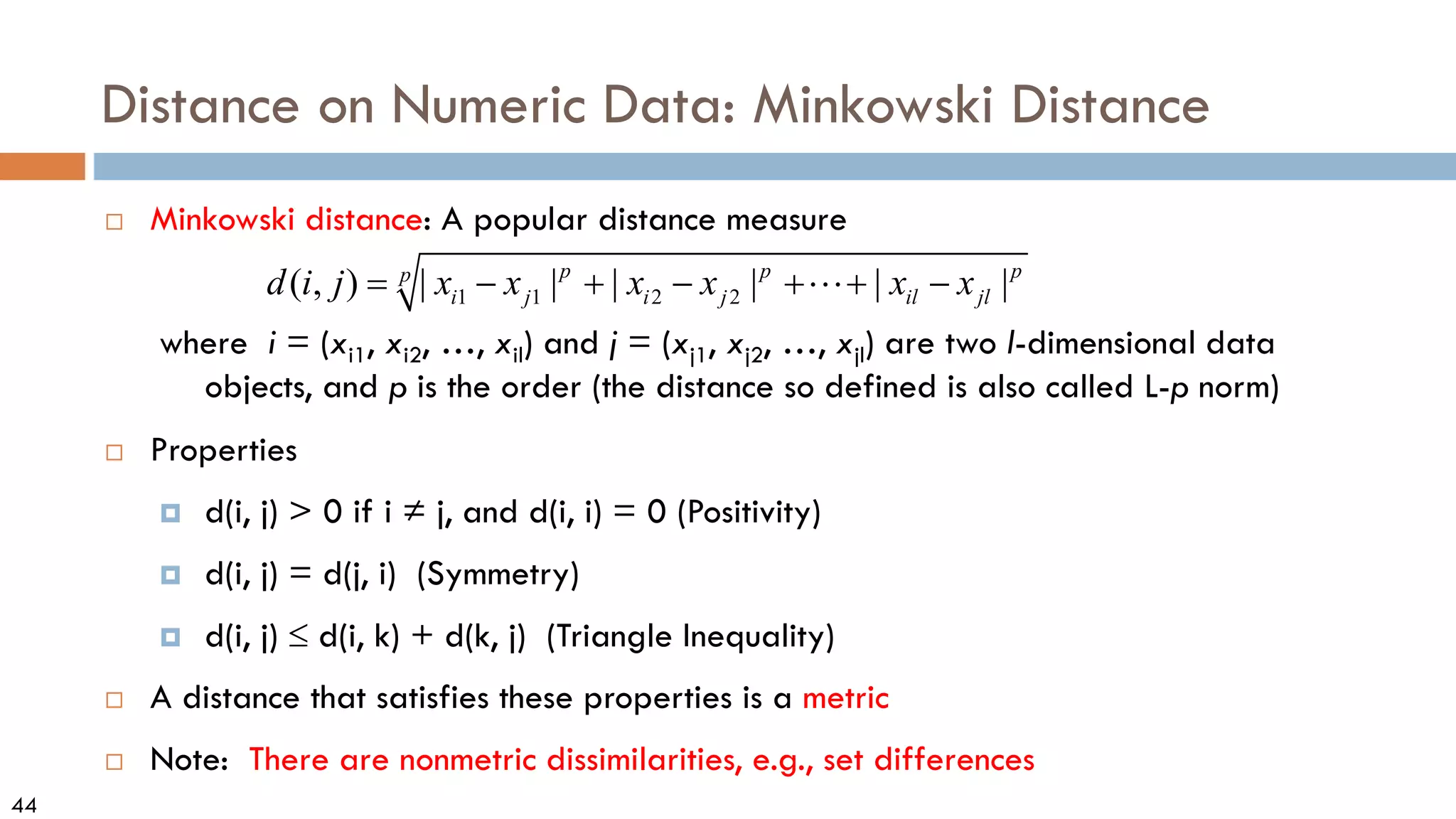

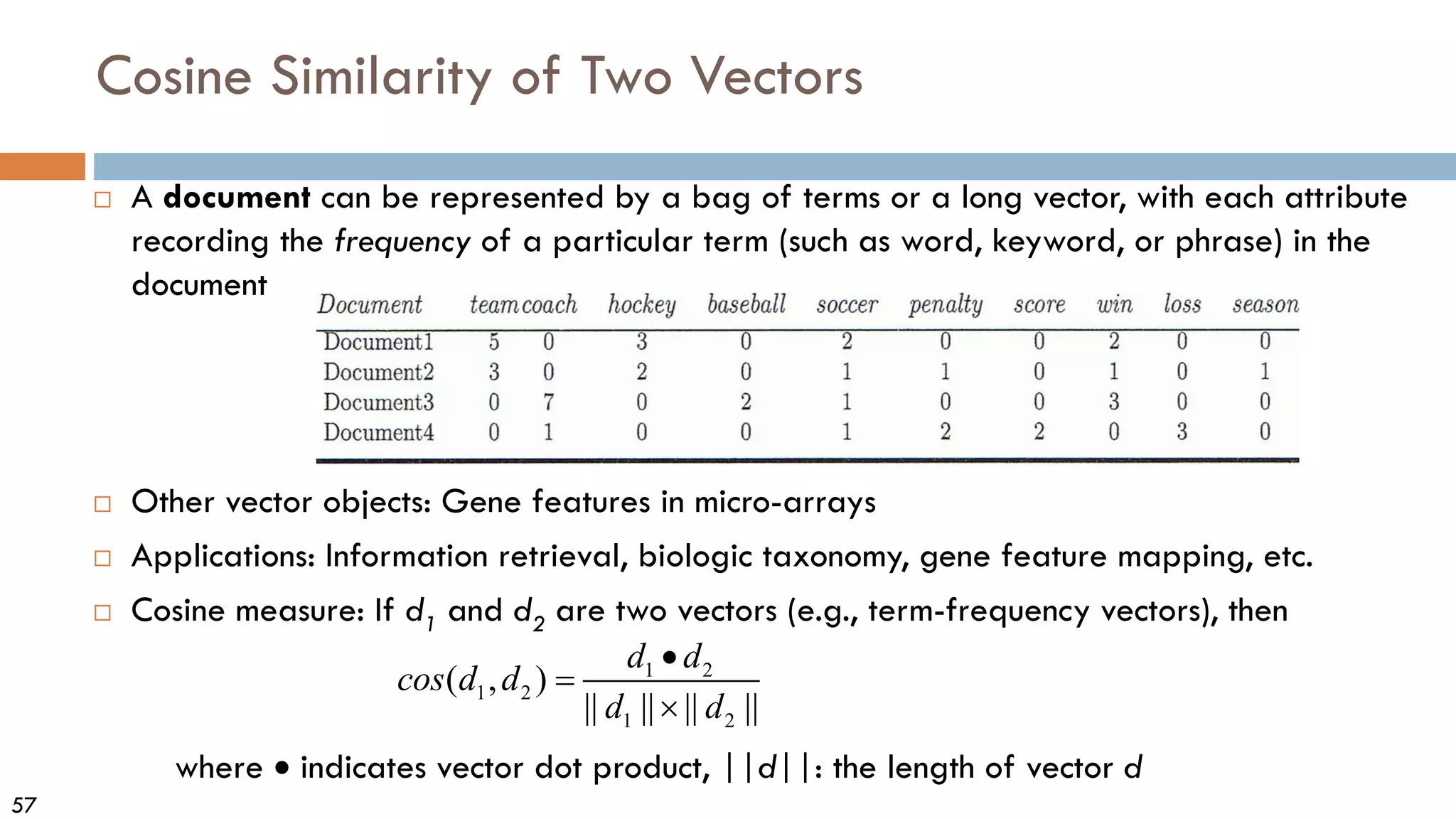

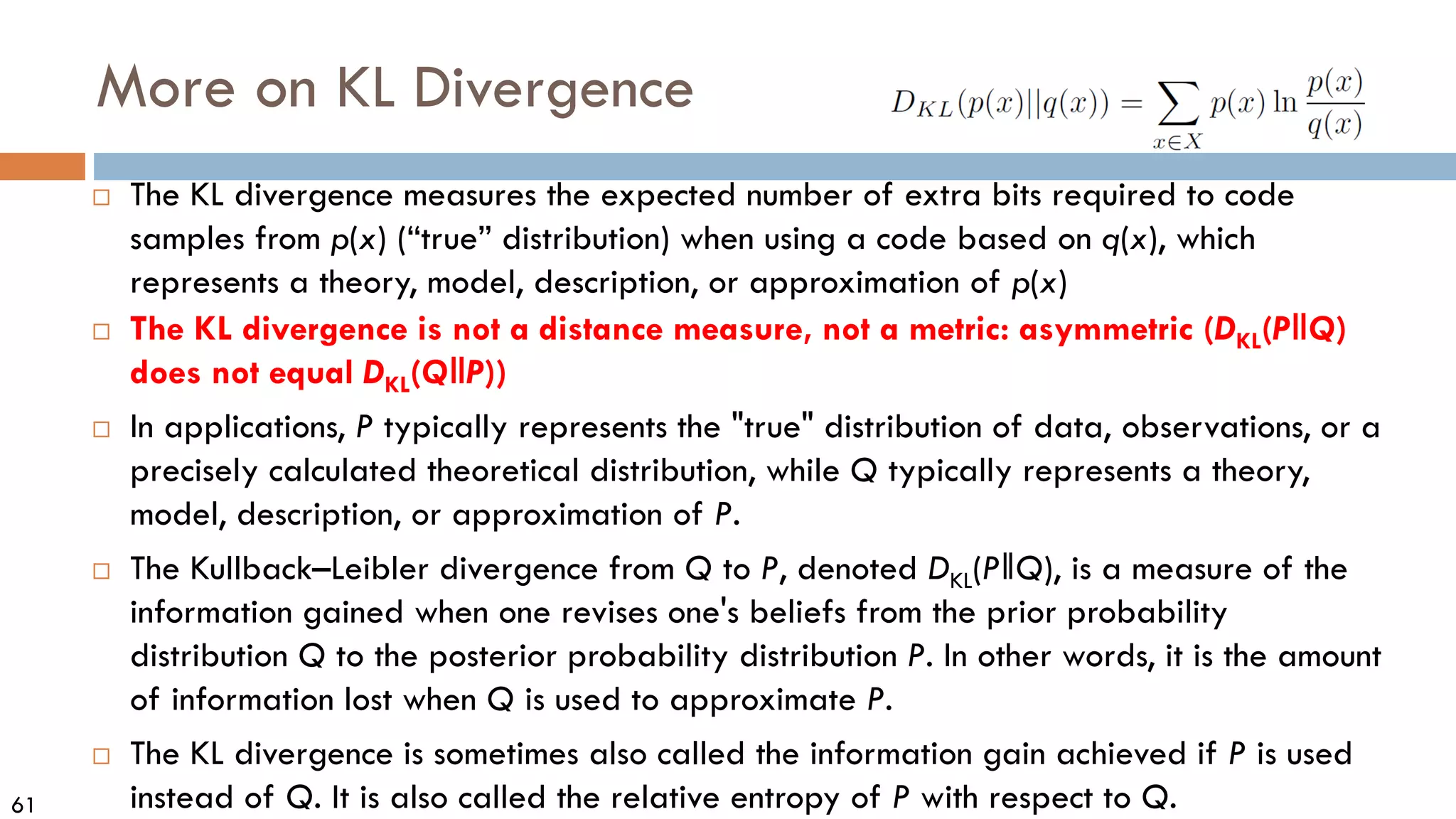

Measures Data Distribution: Variance and Standard Deviation

Variance and standard deviation (sample: s, population: σ)

Variance: (algebraic, scalable computation)

Standard deviation s (or σ) is the square root of variance s2 (orσ2 )

∑

∑ =

=

−

=

−

=

n

i

i

n

i

i x

N

x

N 1

2

2

1

2

2 1

)

(

1

µ

µ

σ

∑ ∑

∑ = =

=

−

−

=

−

−

=

n

i

n

i

i

i

n

i

i x

n

x

n

x

x

n

s

1 1

2

2

1

2

2

]

)

(

1

[

1

1

)

(

1

1

?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-34-2048.jpg)

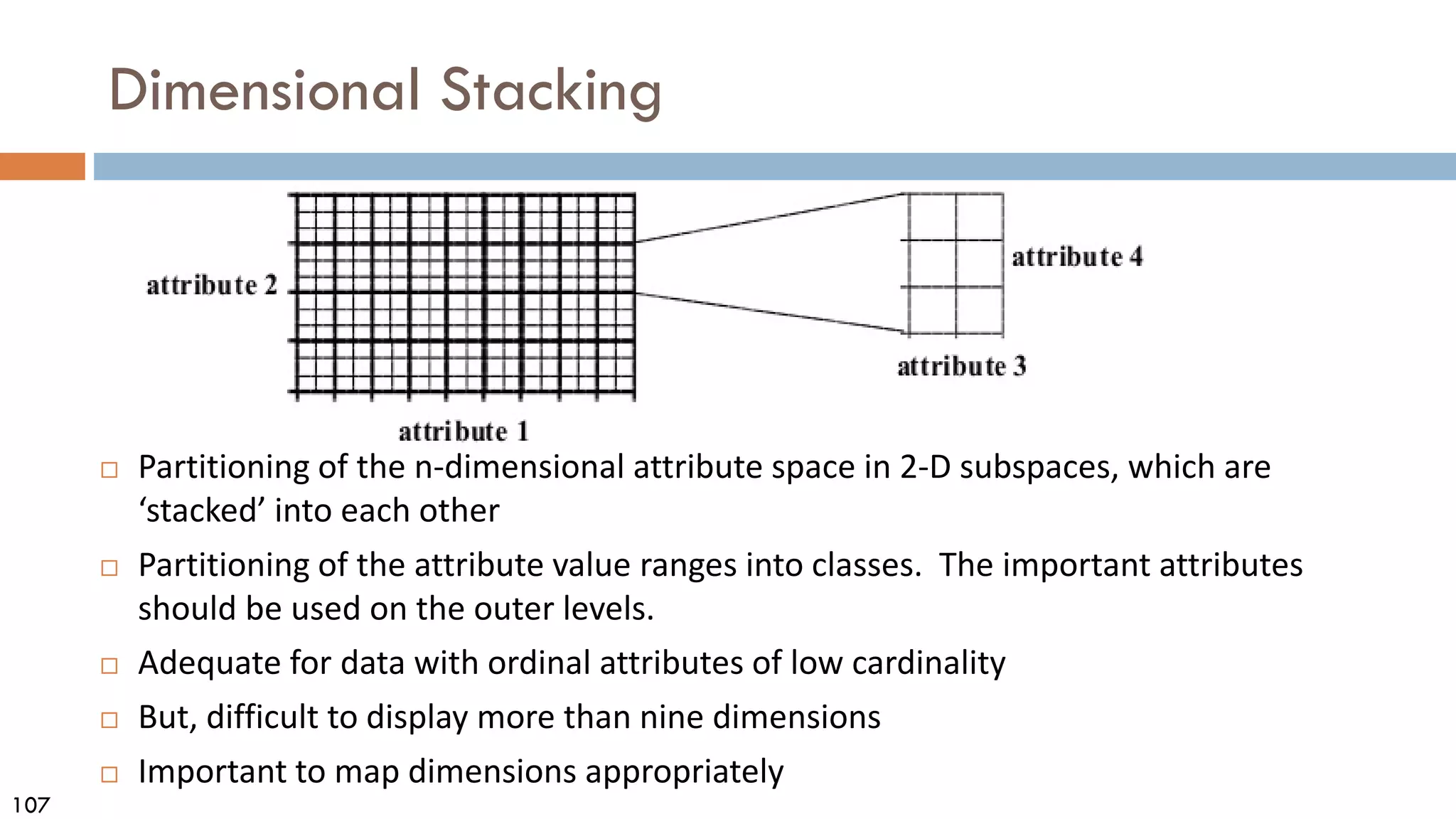

![38

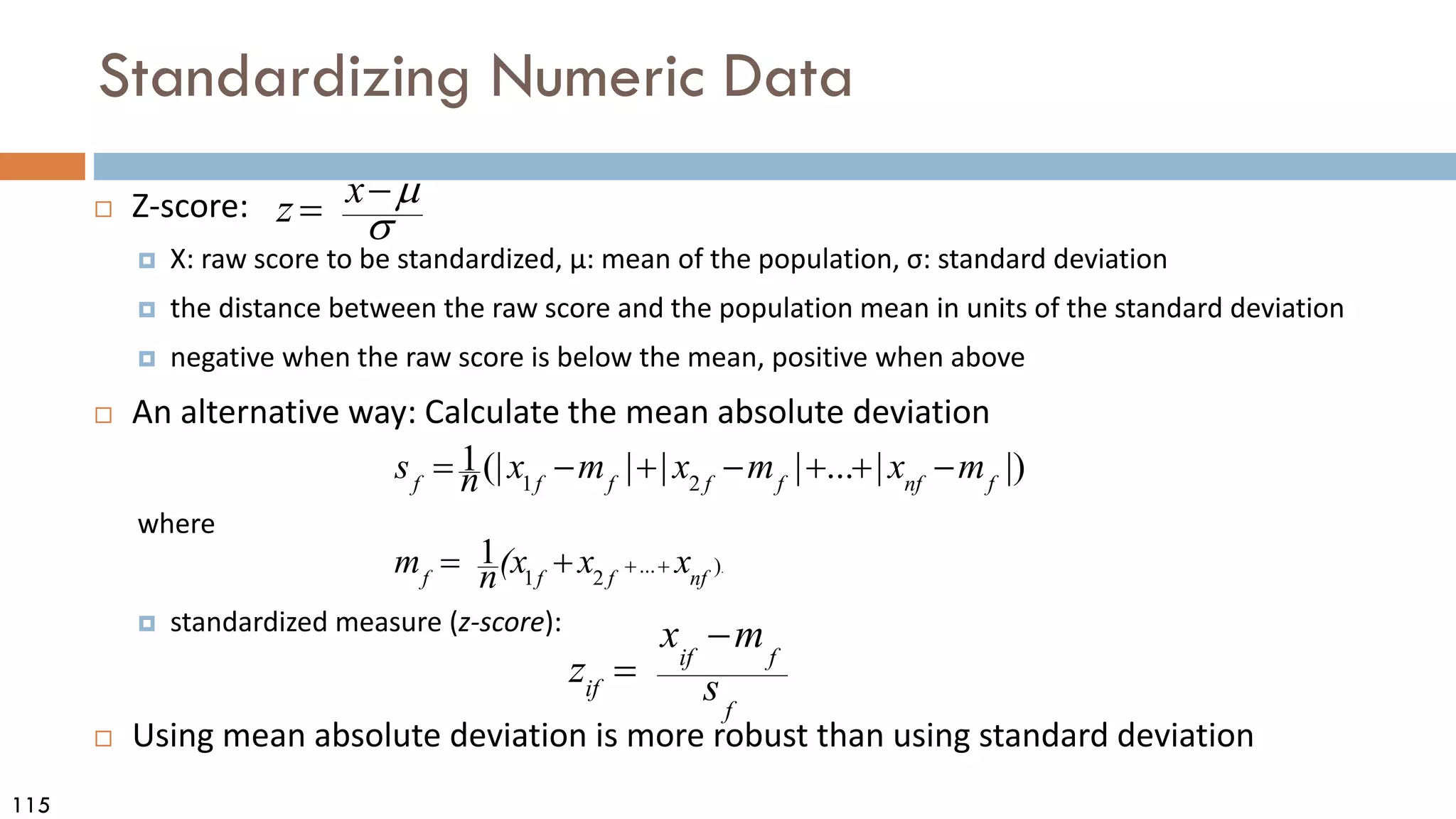

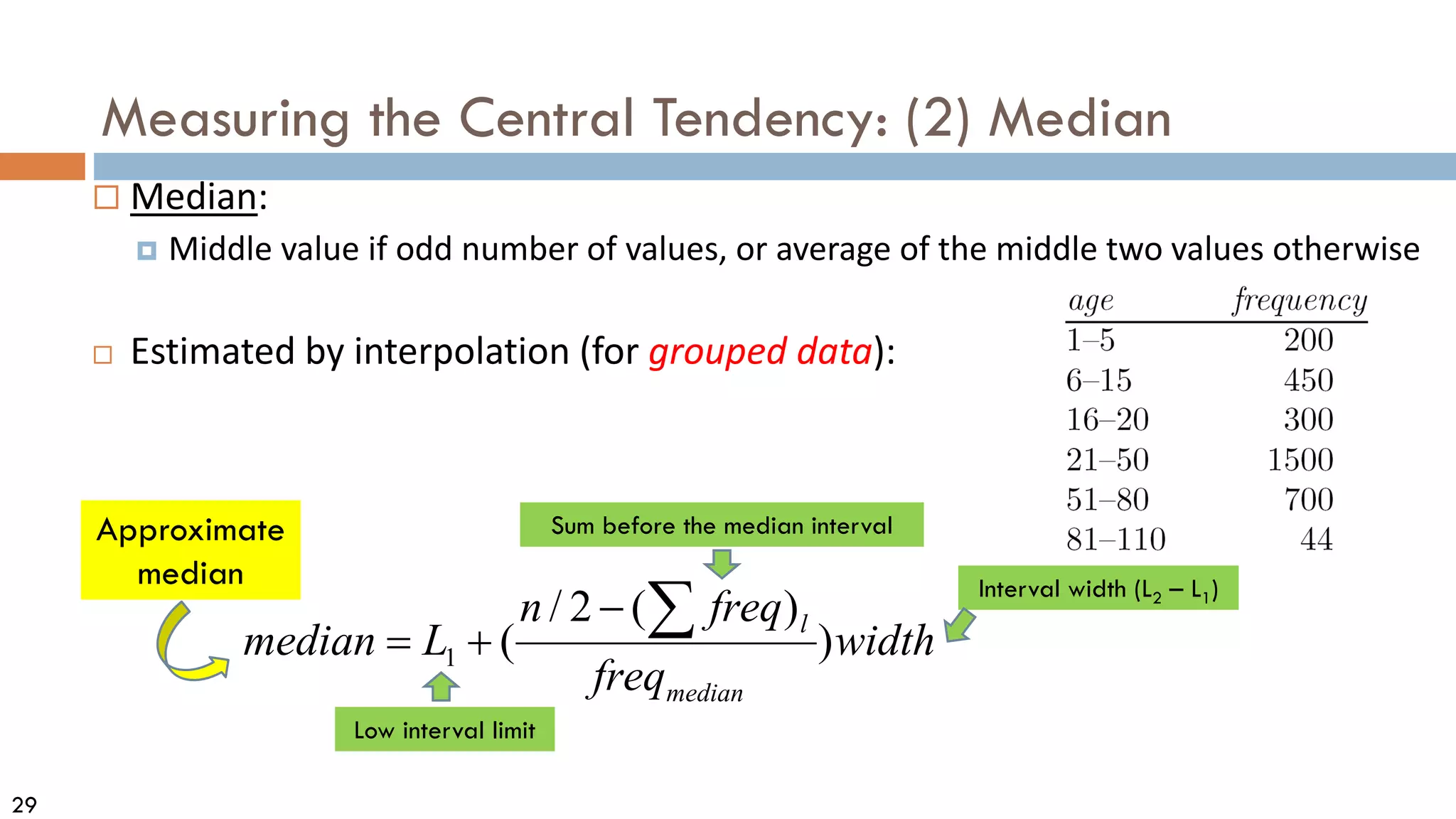

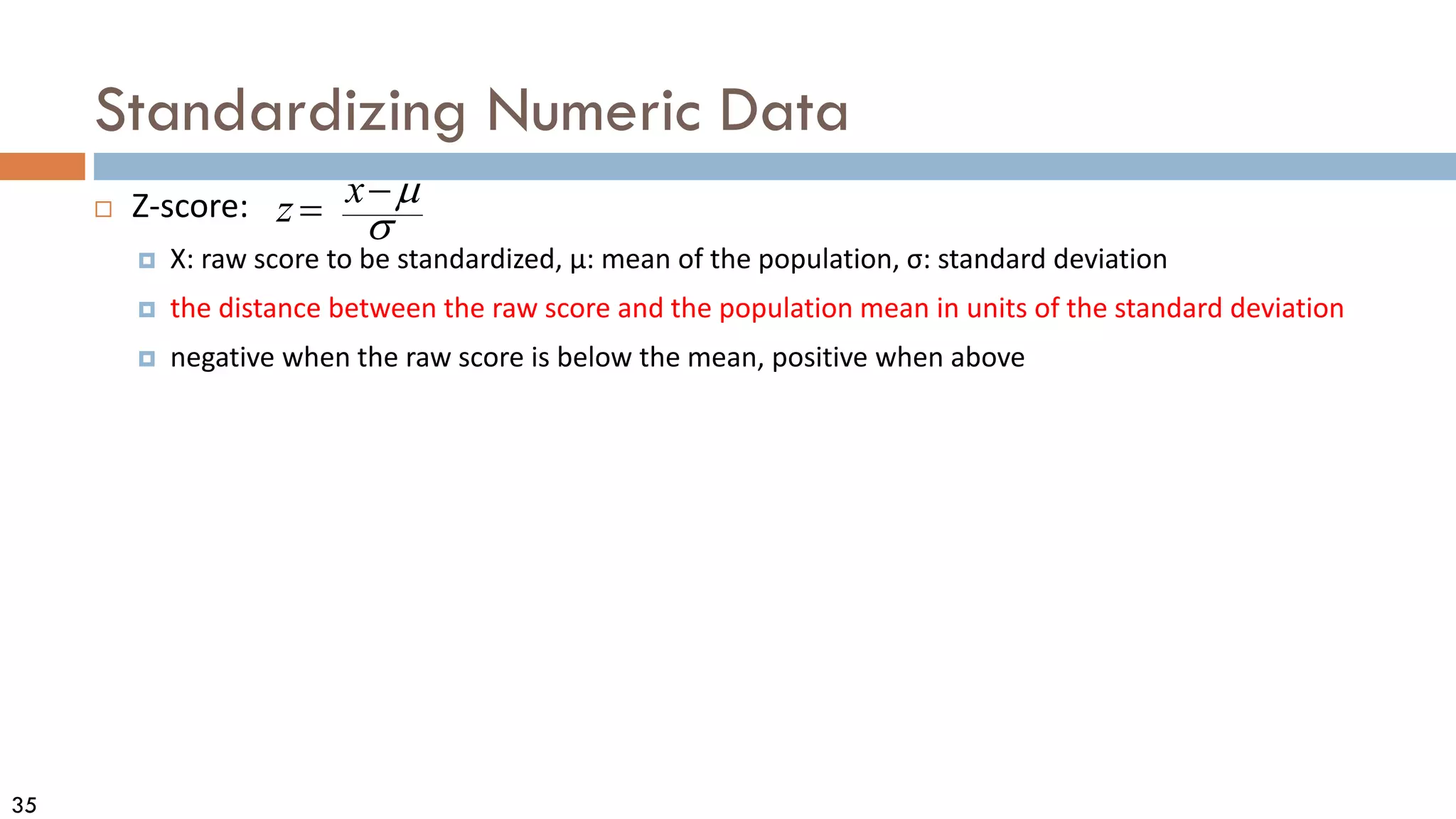

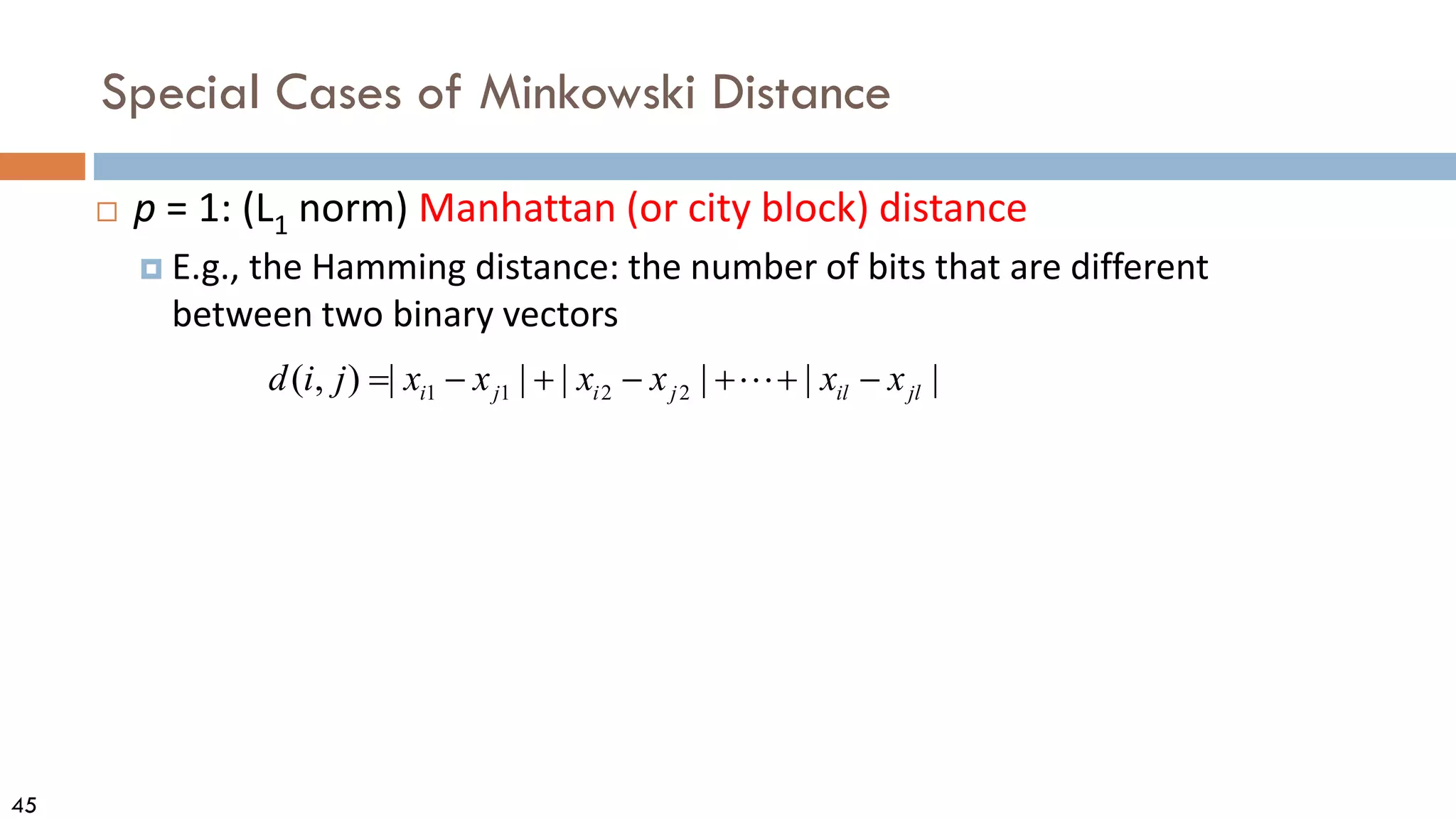

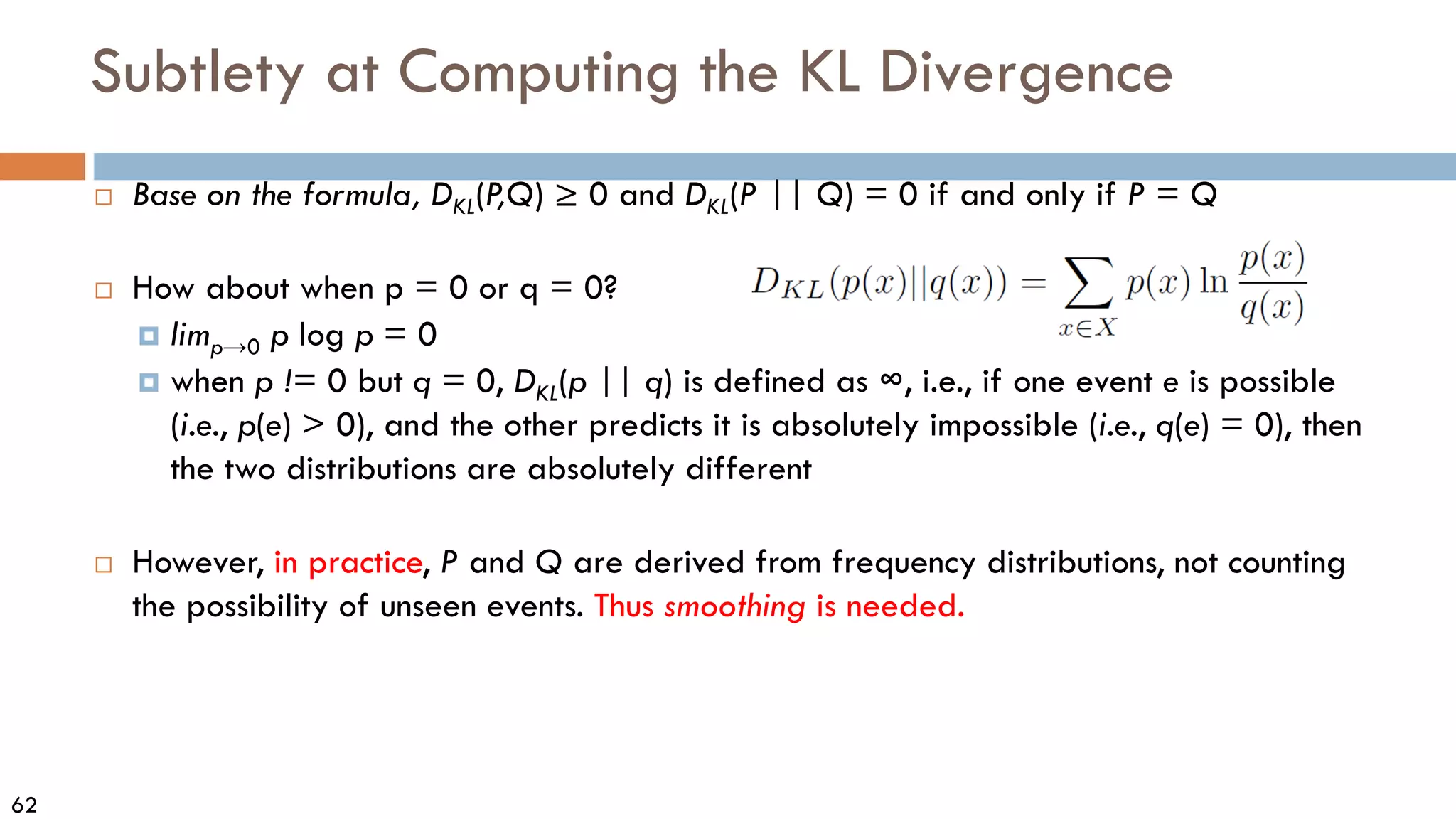

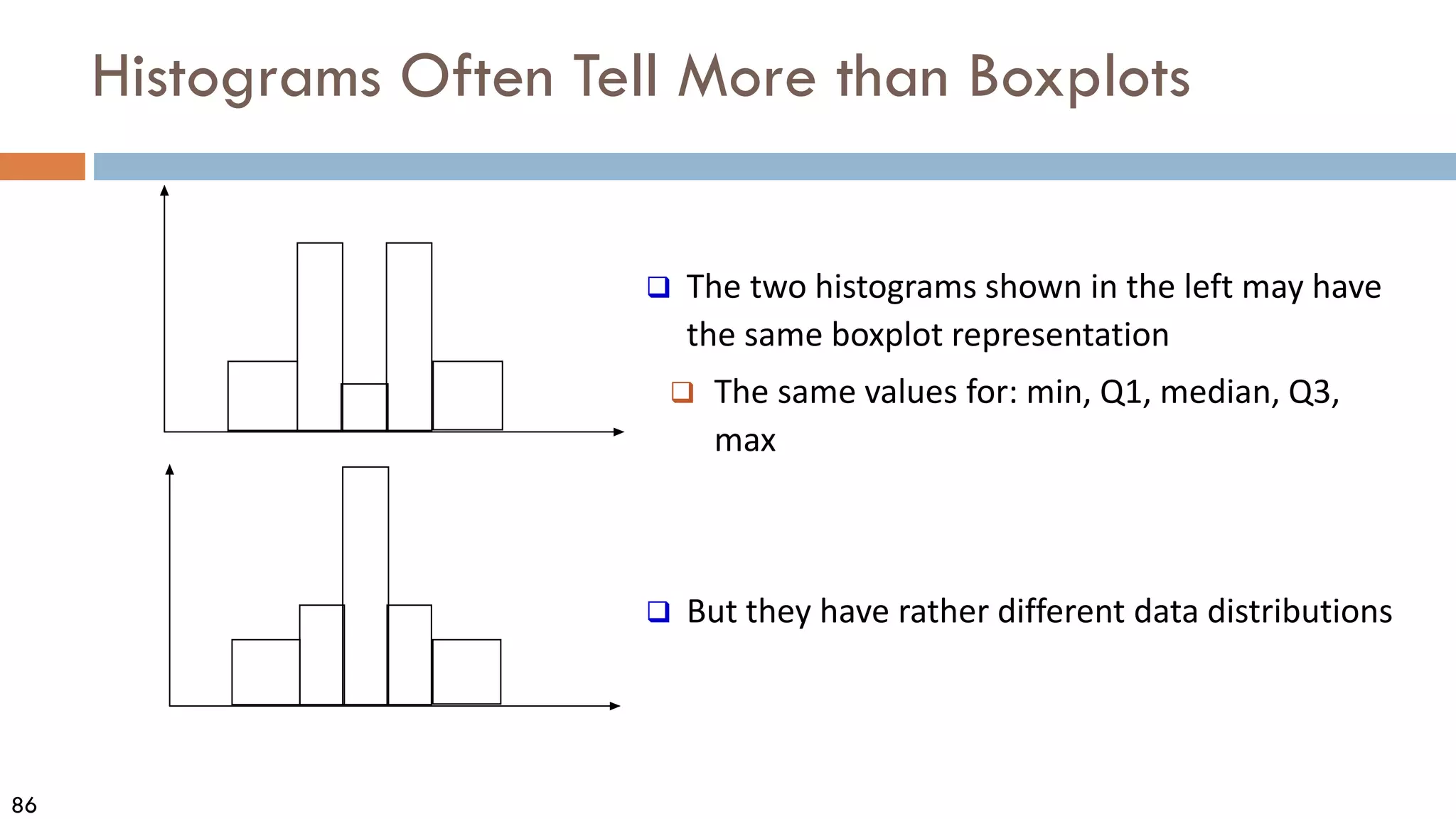

Similarity, Dissimilarity, and Proximity

Similarity measure or similarity function

A real-valued function that quantifies the similarity between two objects

Measure how two data objects are alike: The higher value, the more alike

Often falls in the range [0,1]: 0: no similarity; 1: completely similar](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-38-2048.jpg)

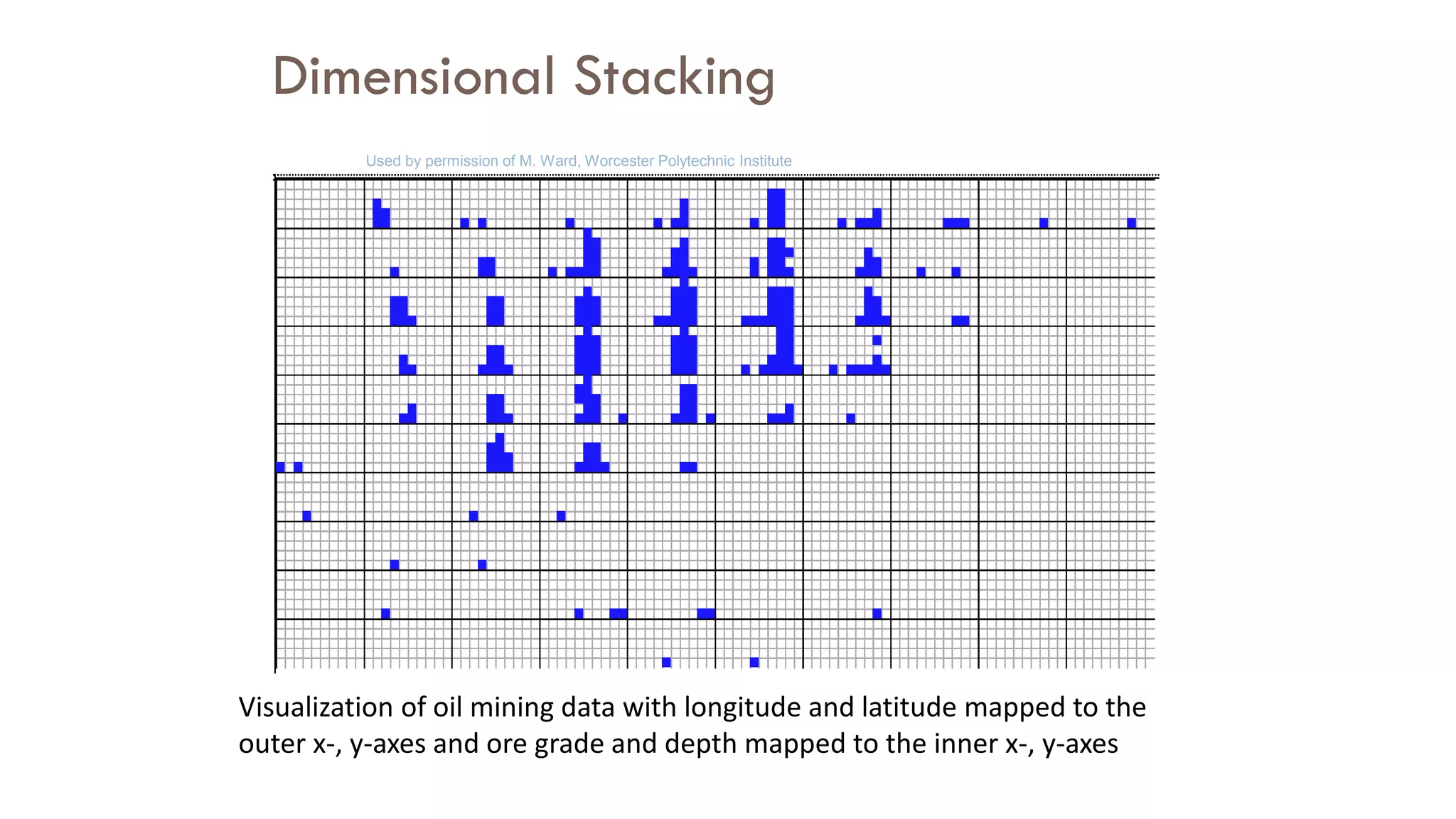

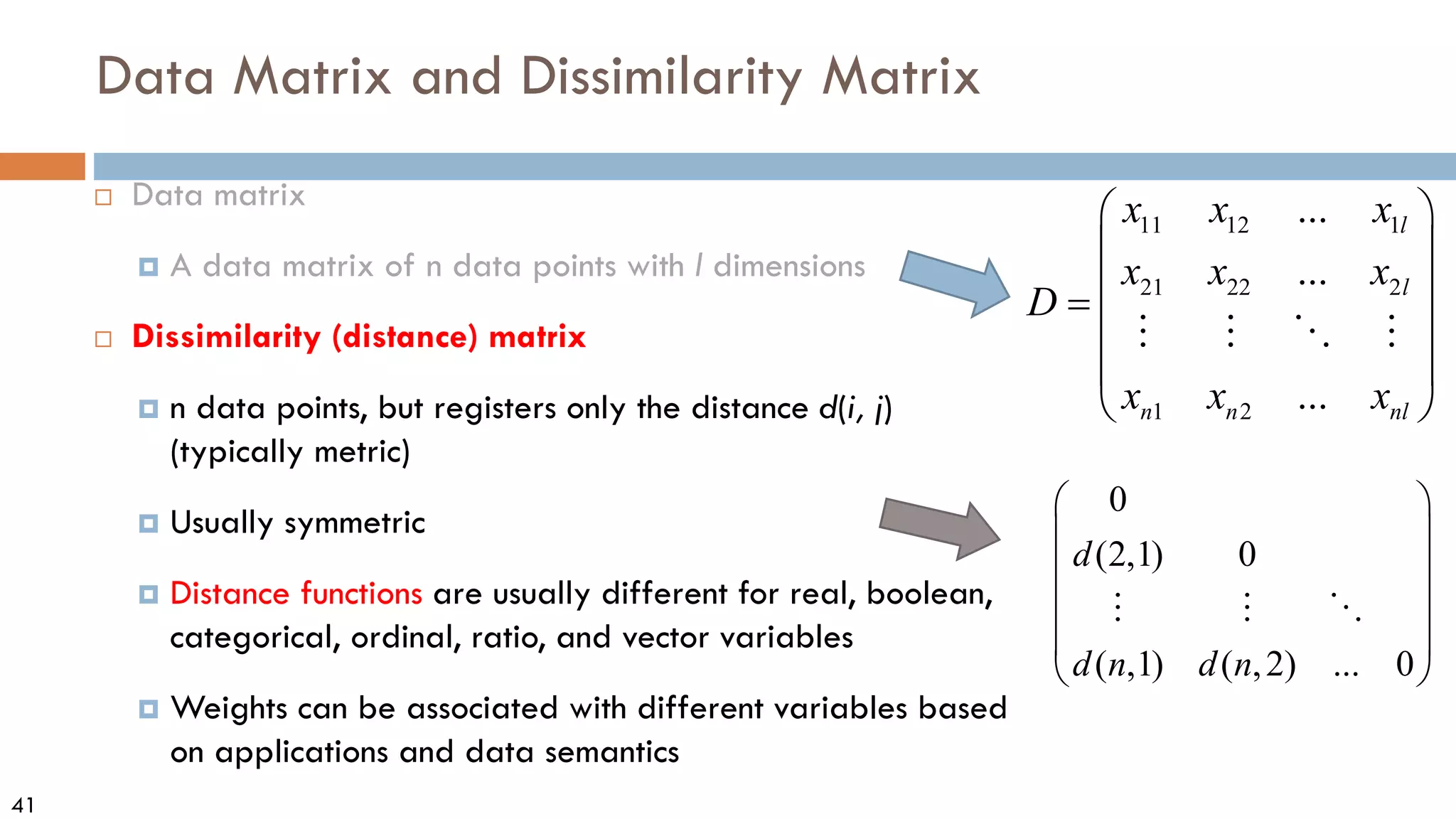

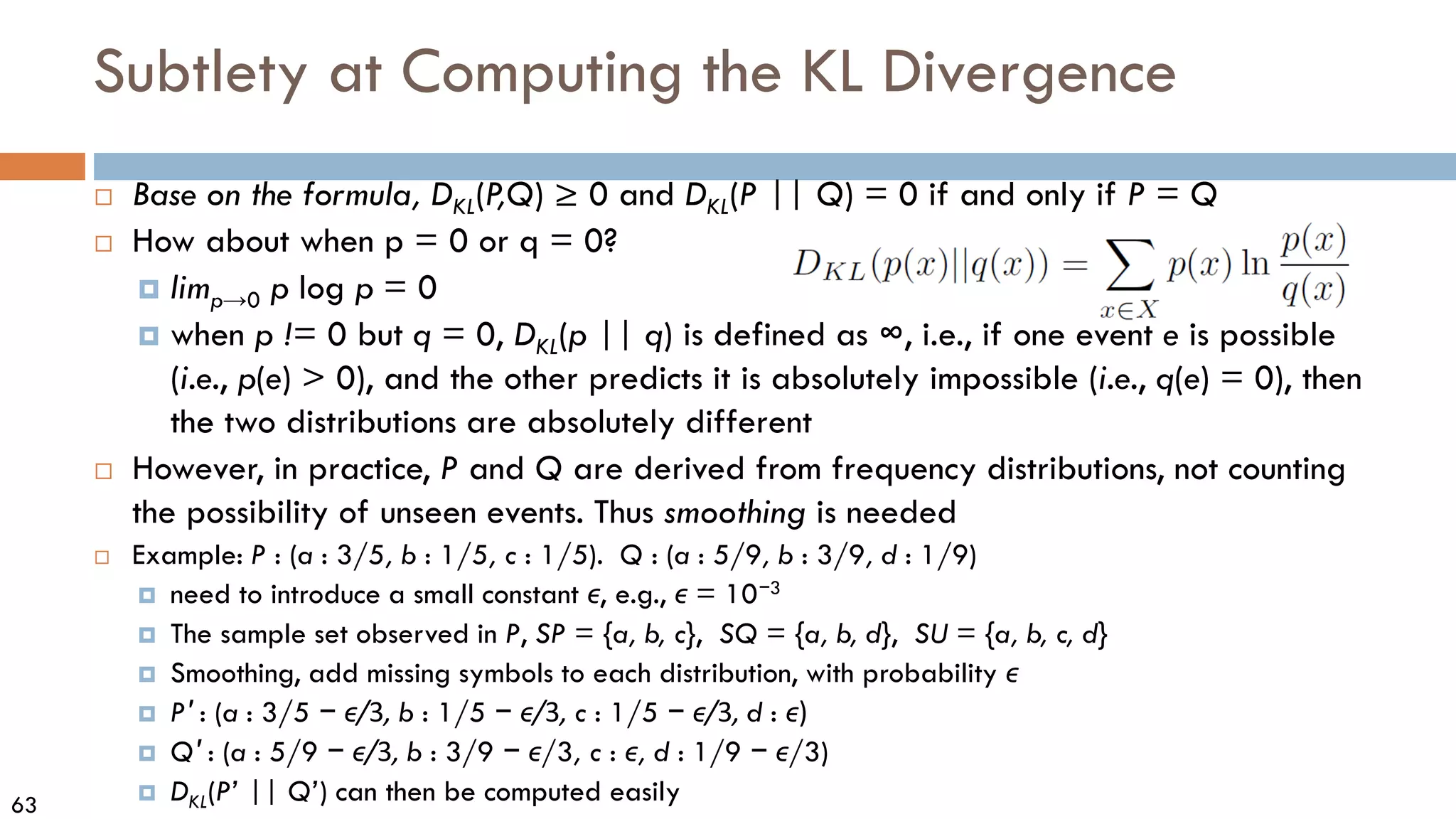

![39

Similarity, Dissimilarity, and Proximity

Similarity measure or similarity function

A real-valued function that quantifies the similarity between two objects

Measure how two data objects are alike: The higher value, the more alike

Often falls in the range [0,1]: 0: no similarity; 1: completely similar

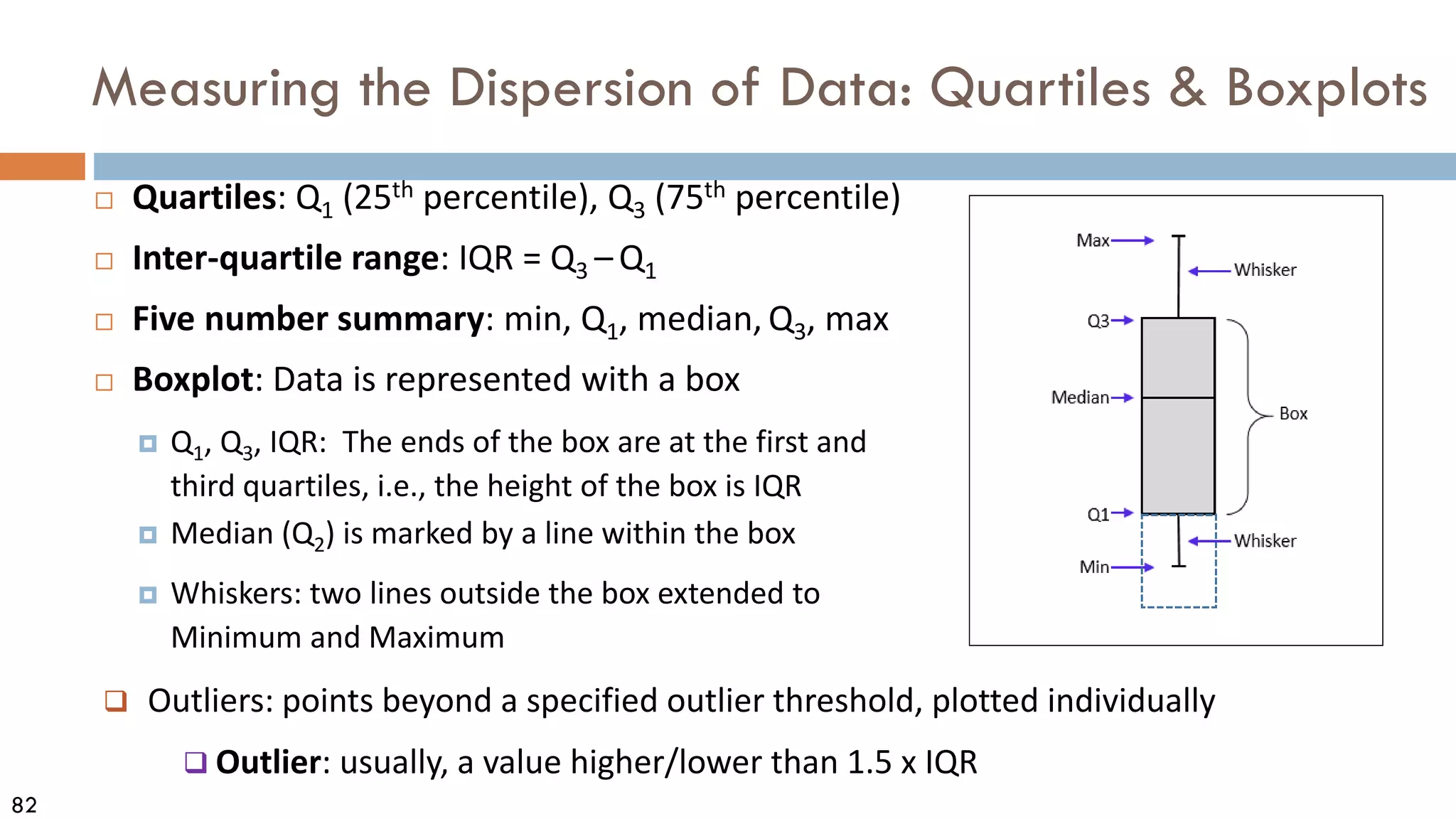

Dissimilarity (or distance) measure

Numerical measure of how different two data objects are

In some sense, the inverse of similarity: The lower, the more alike

Minimum dissimilarity is often 0 (i.e., completely similar)

Range [0, 1] or [0, ∞) , depending on the definition

Proximity usually refers to either similarity or dissimilarity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-39-2048.jpg)

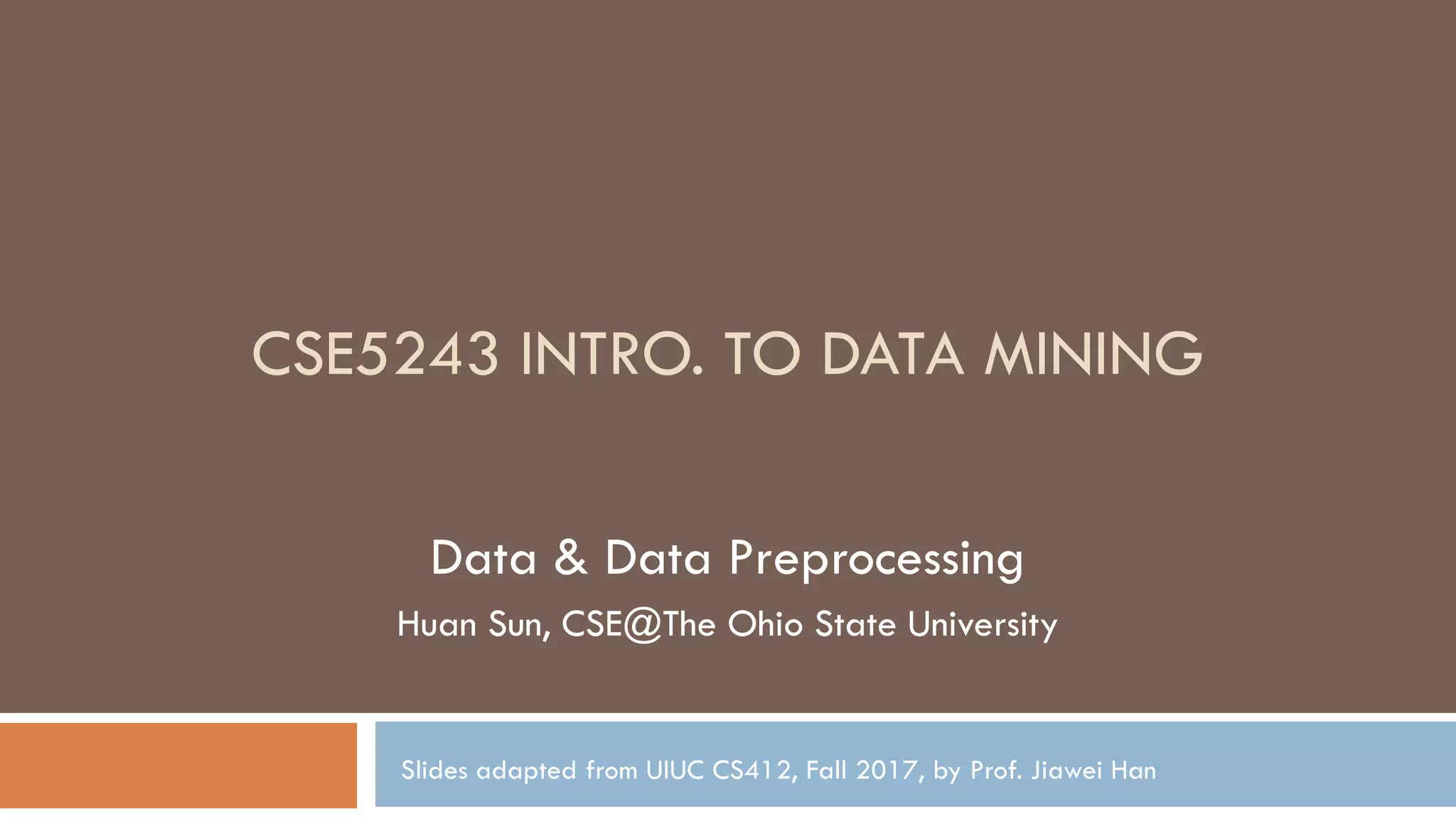

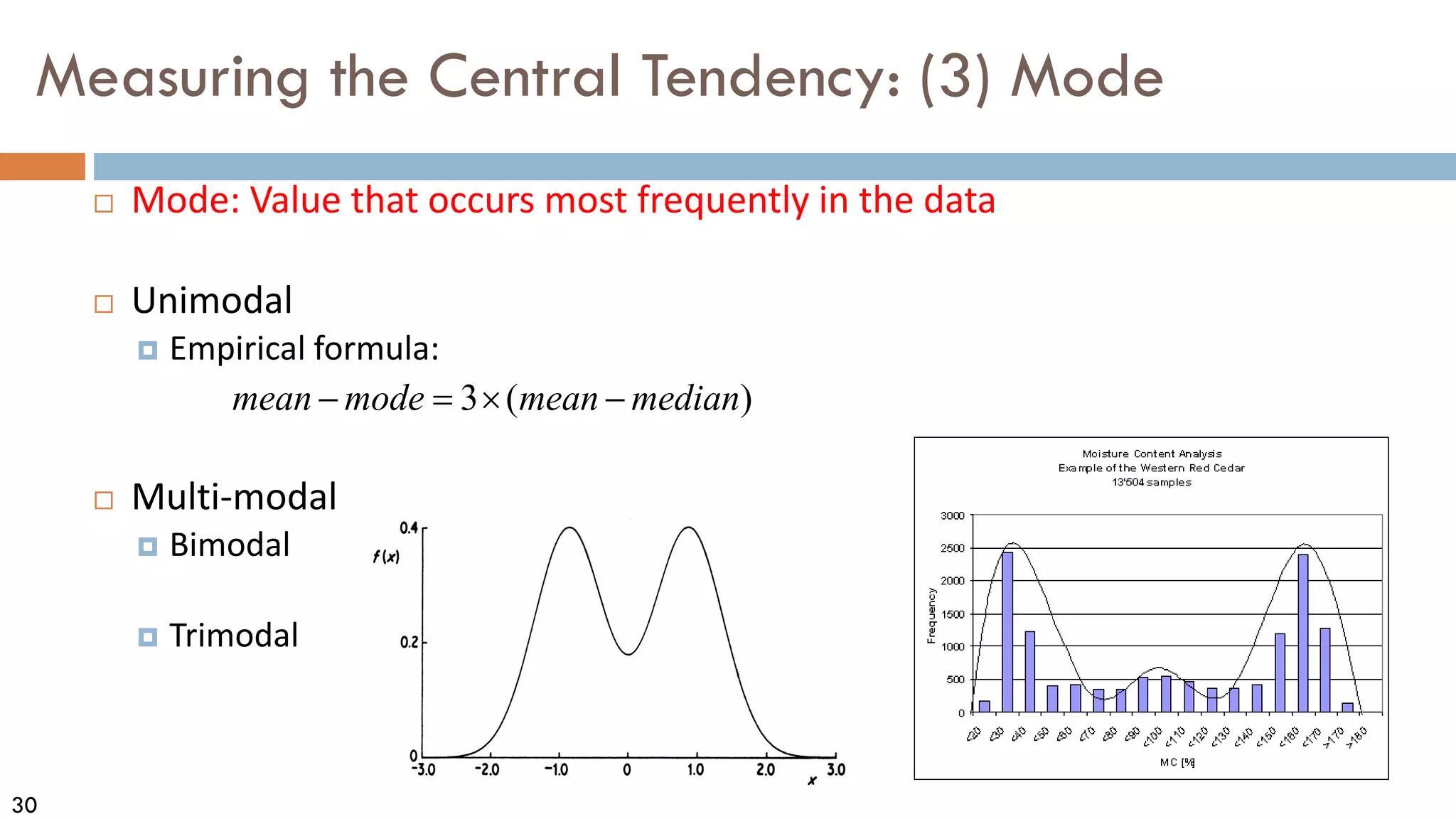

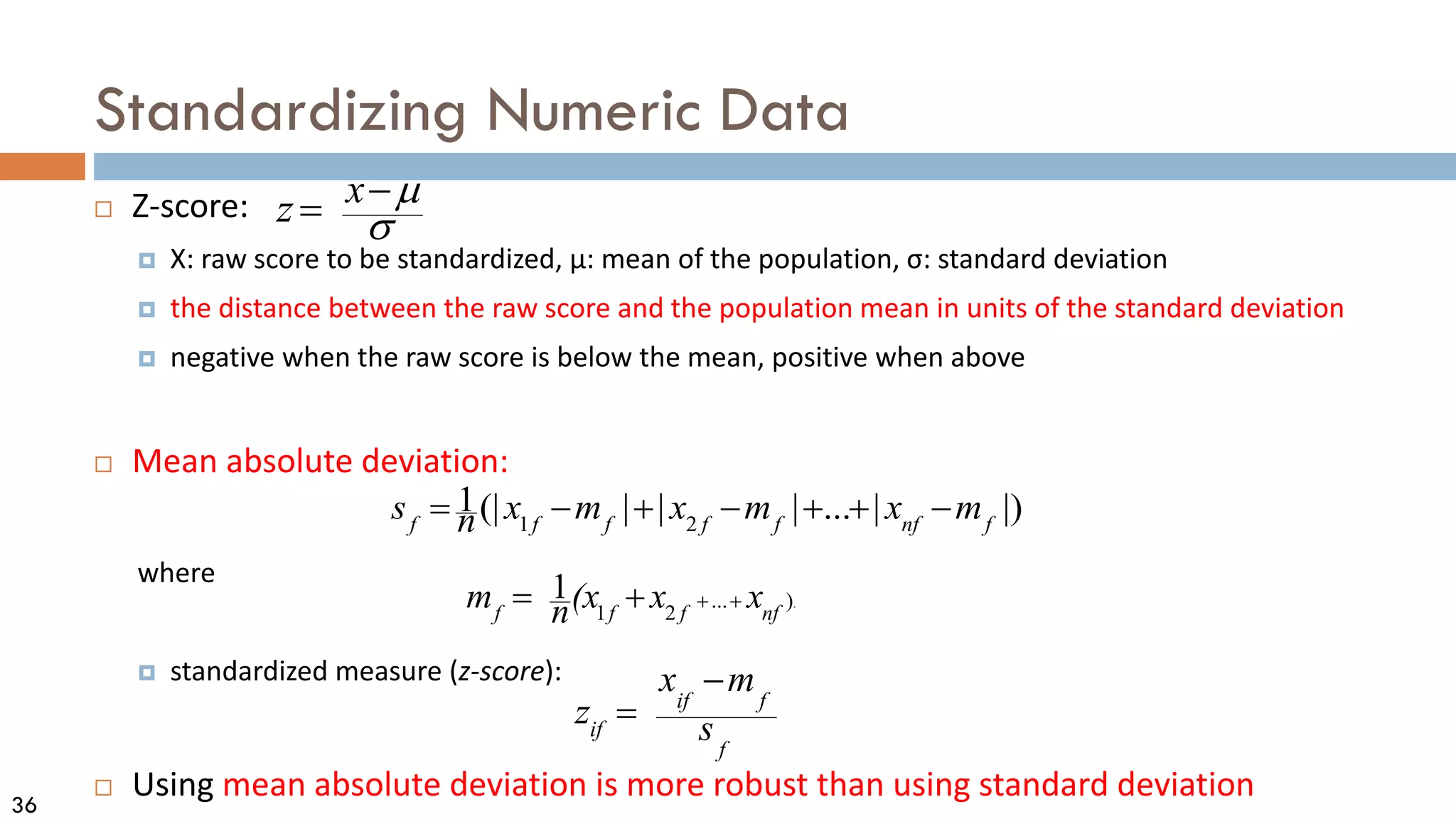

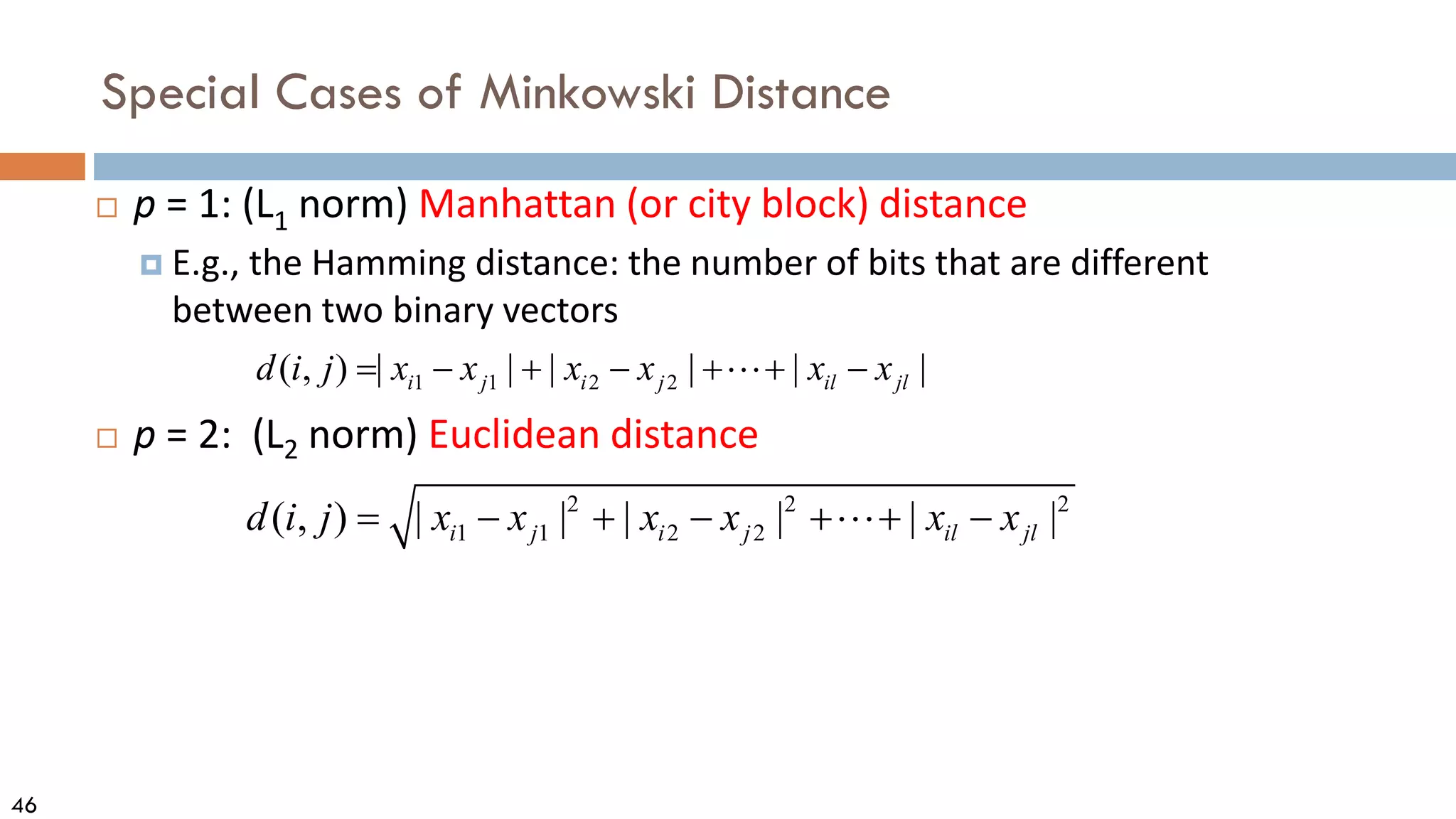

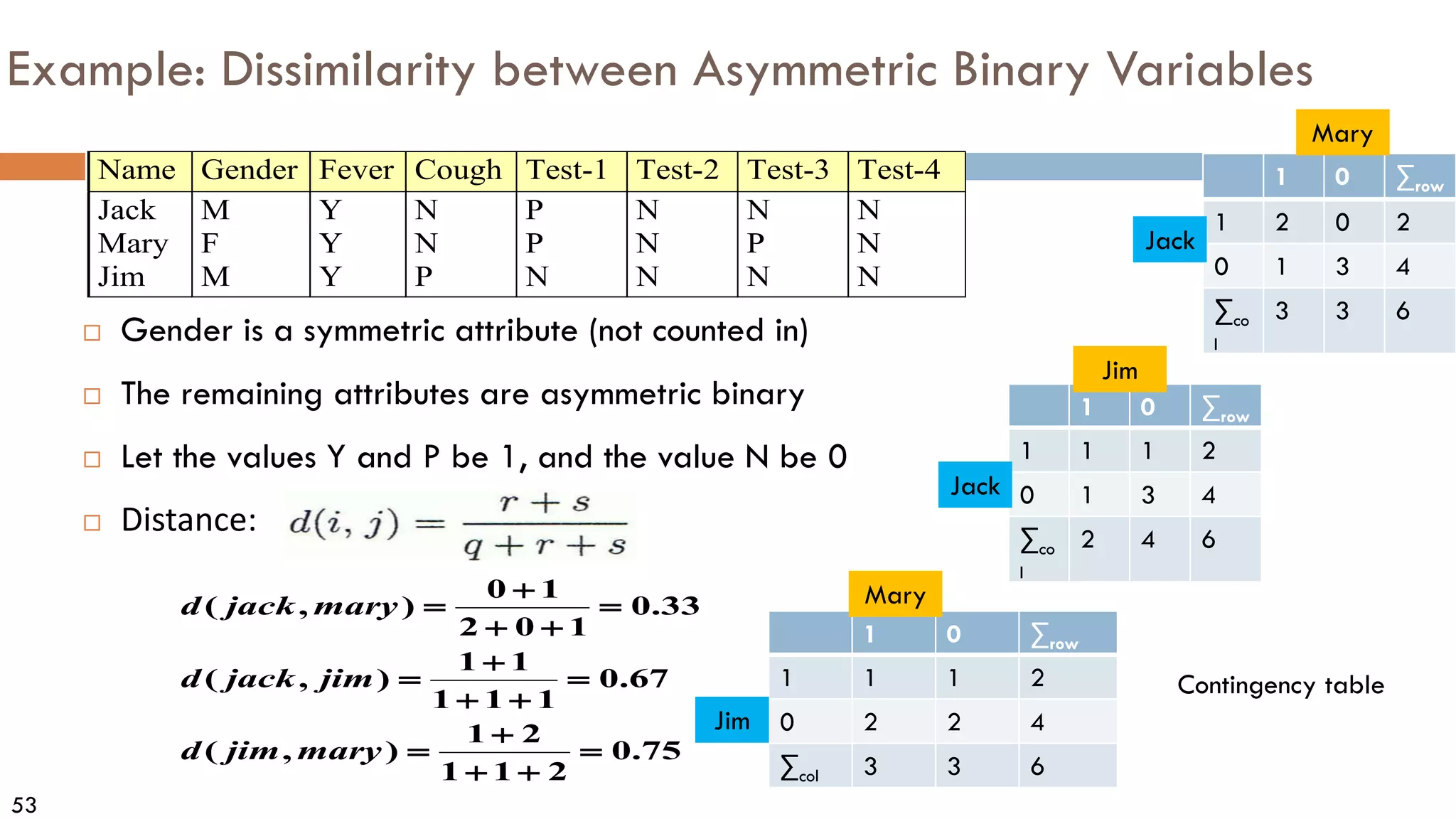

![55

Ordinal Variables

An ordinal variable can be discrete or continuous

Order is important, e.g., rank (e.g., freshman, sophomore, junior, senior)

Can be treated like interval-scaled

Replace an ordinal variable value by its rank:

Map the range of each variable onto [0, 1] by replacing i-th object in

the f-th variable by

Example: freshman: 0; sophomore: 1/3; junior: 2/3; senior 1

Then distance: d(freshman, senior) = 1, d(junior, senior) = 1/3

Compute the dissimilarity using methods for interval-scaled variables

1

1

if

if

f

r

z

M

−

=

−

{1,..., }

if f

r M

∈](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-55-2048.jpg)

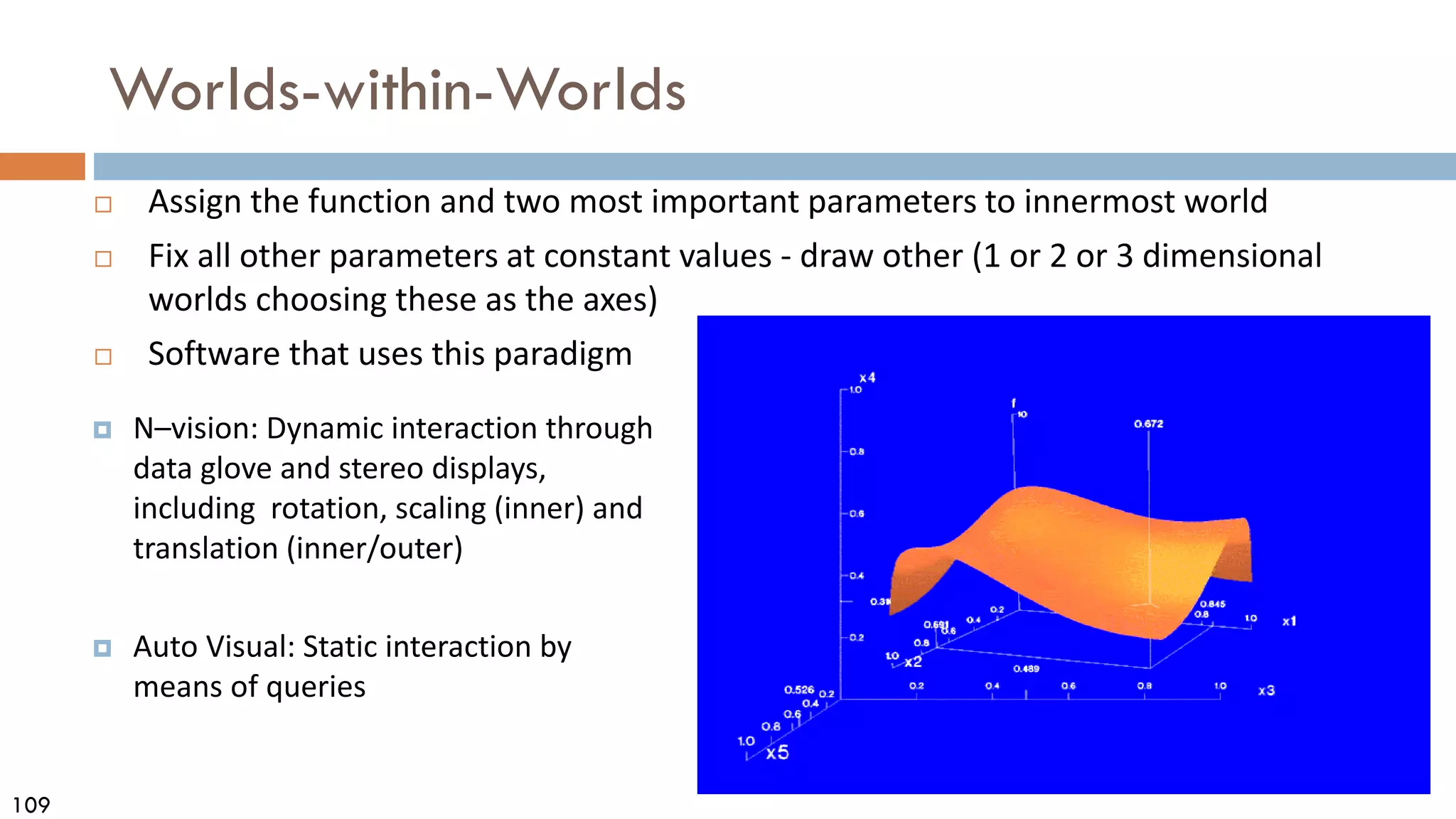

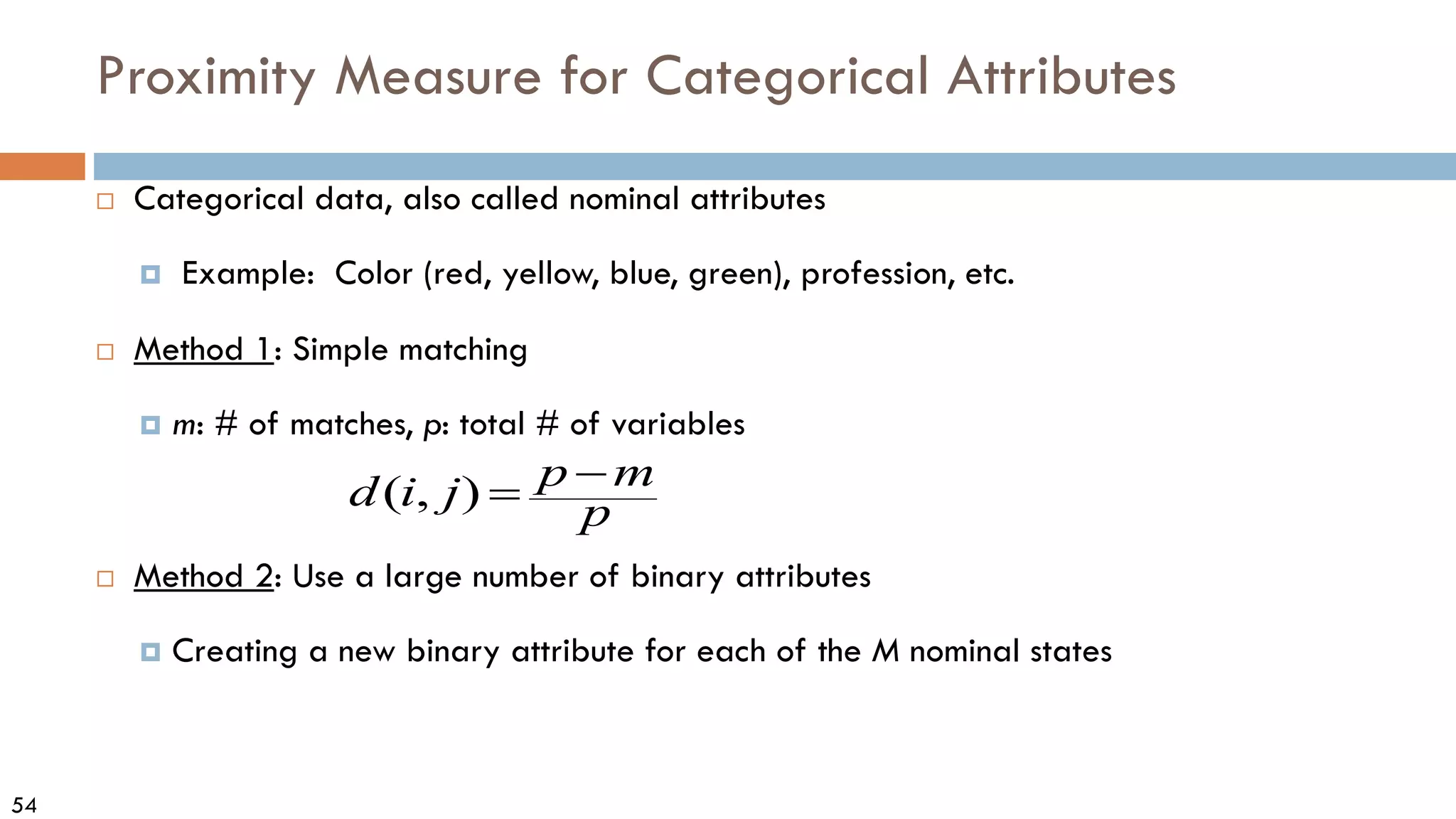

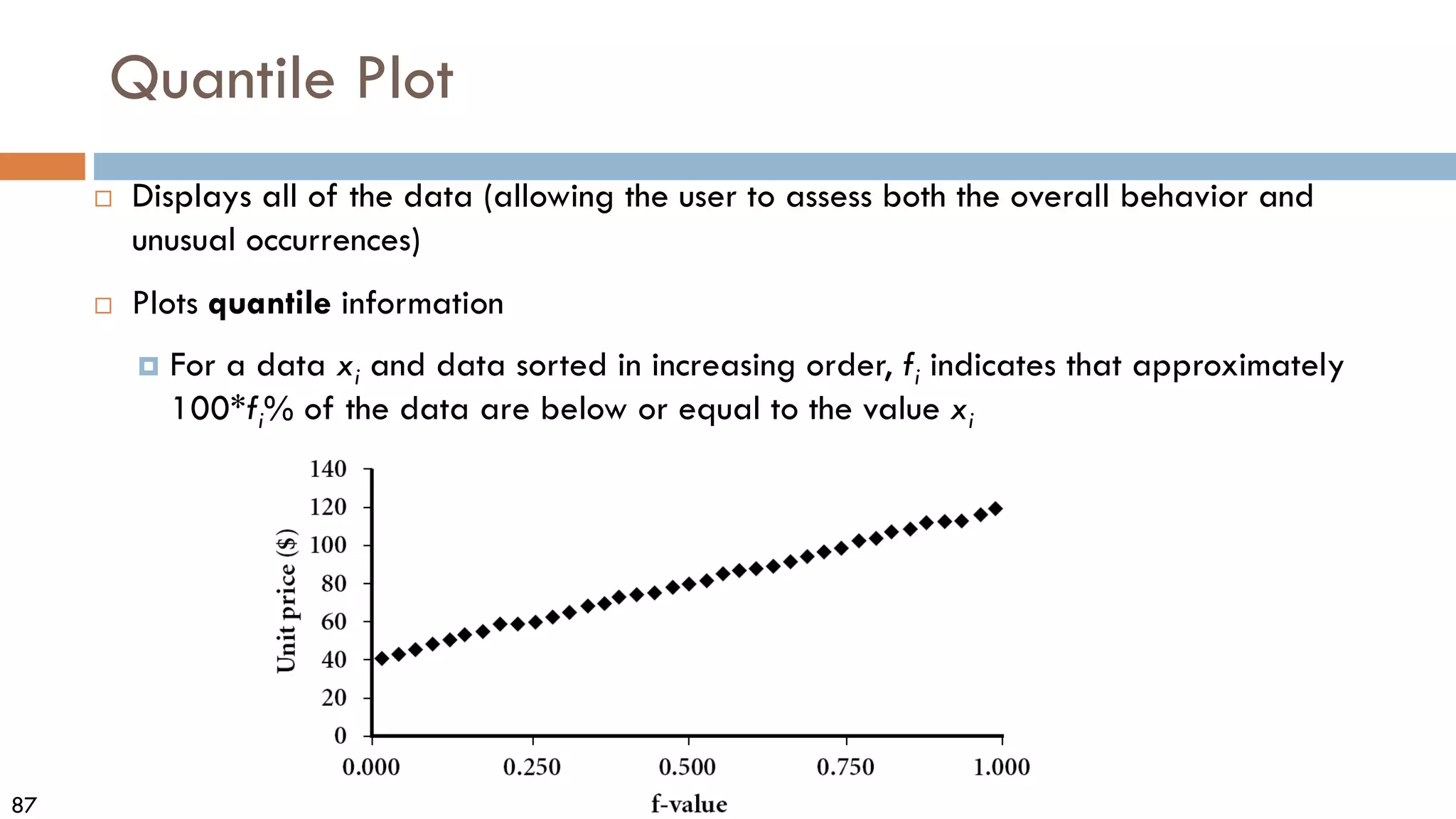

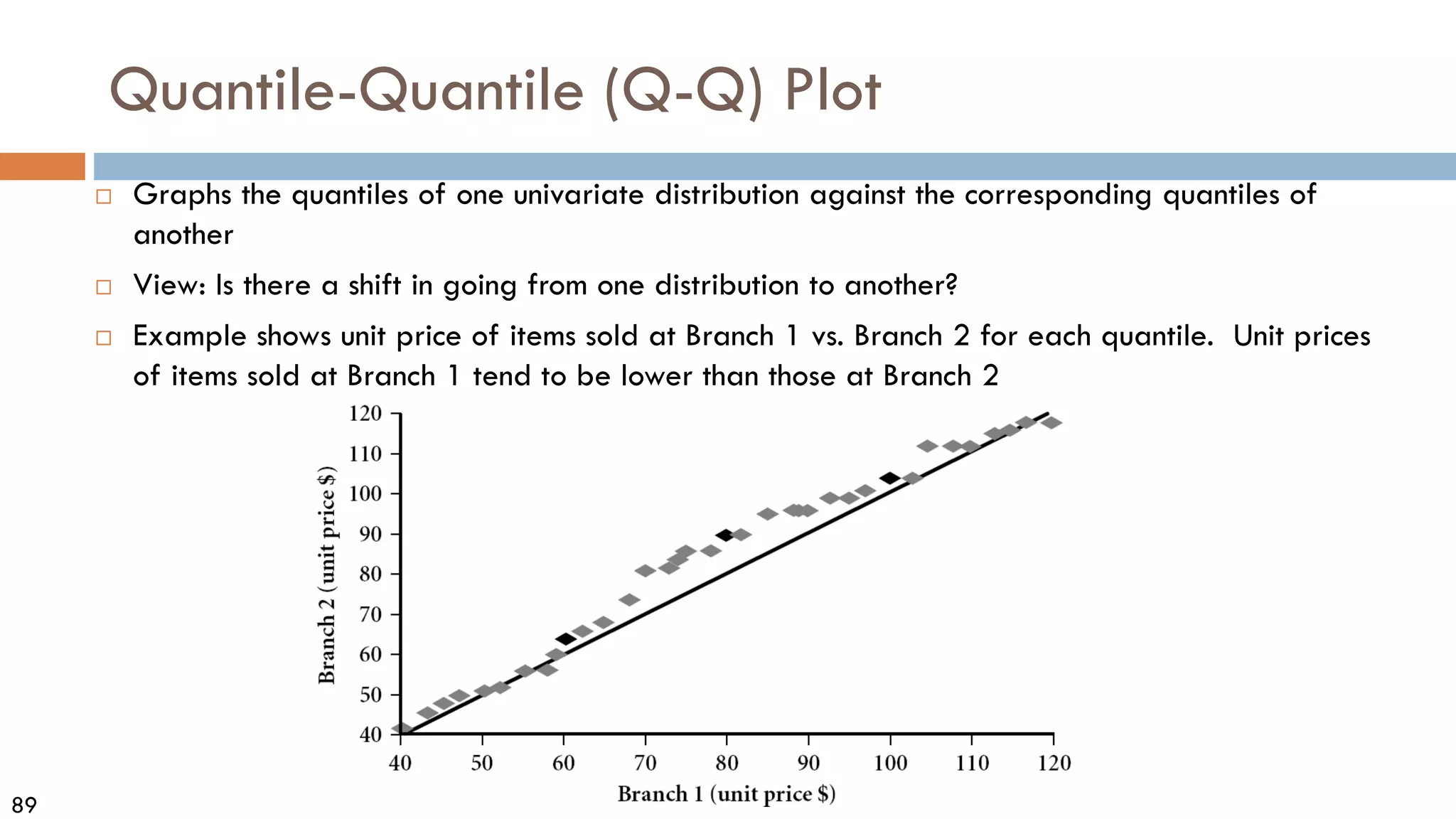

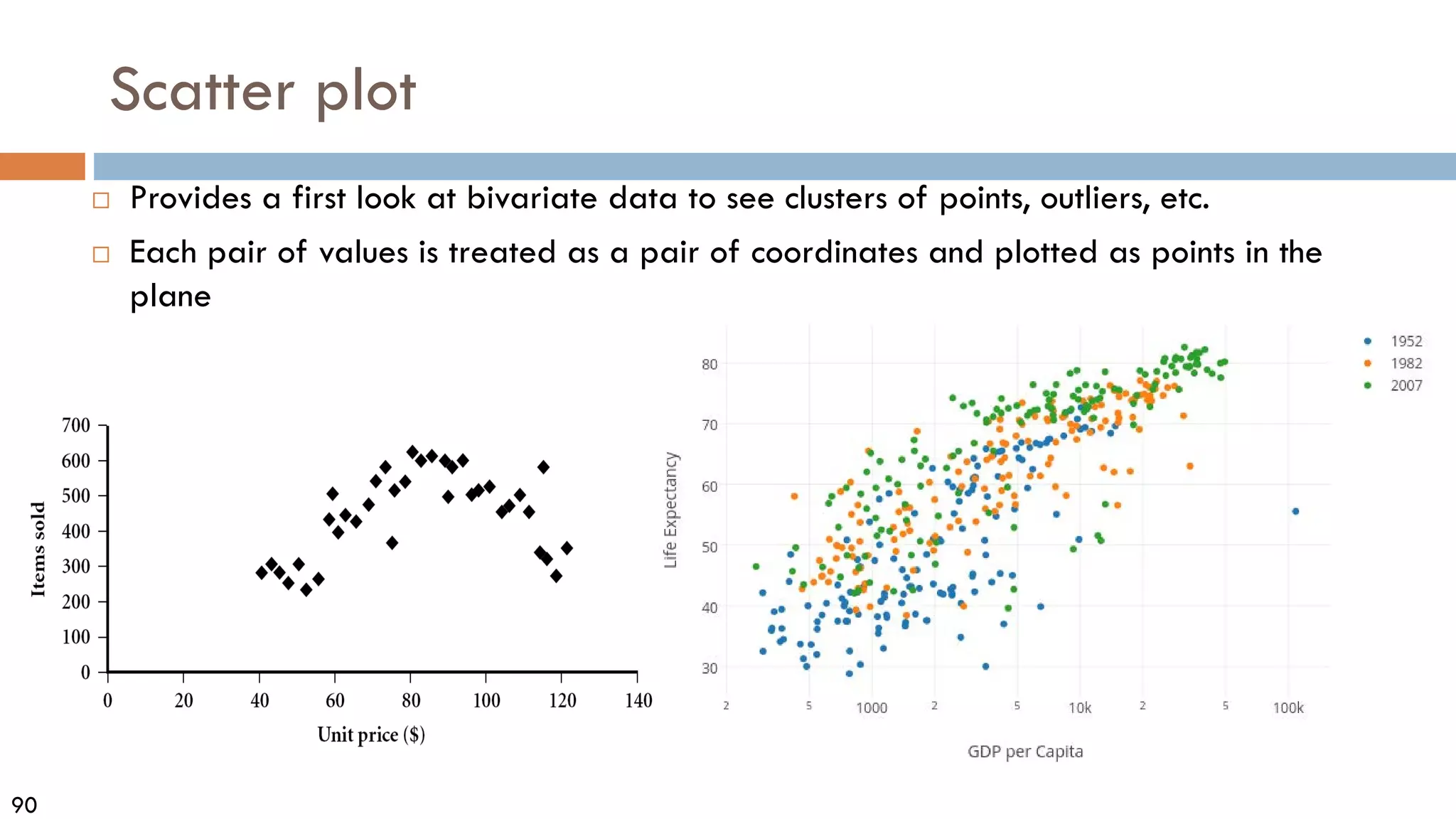

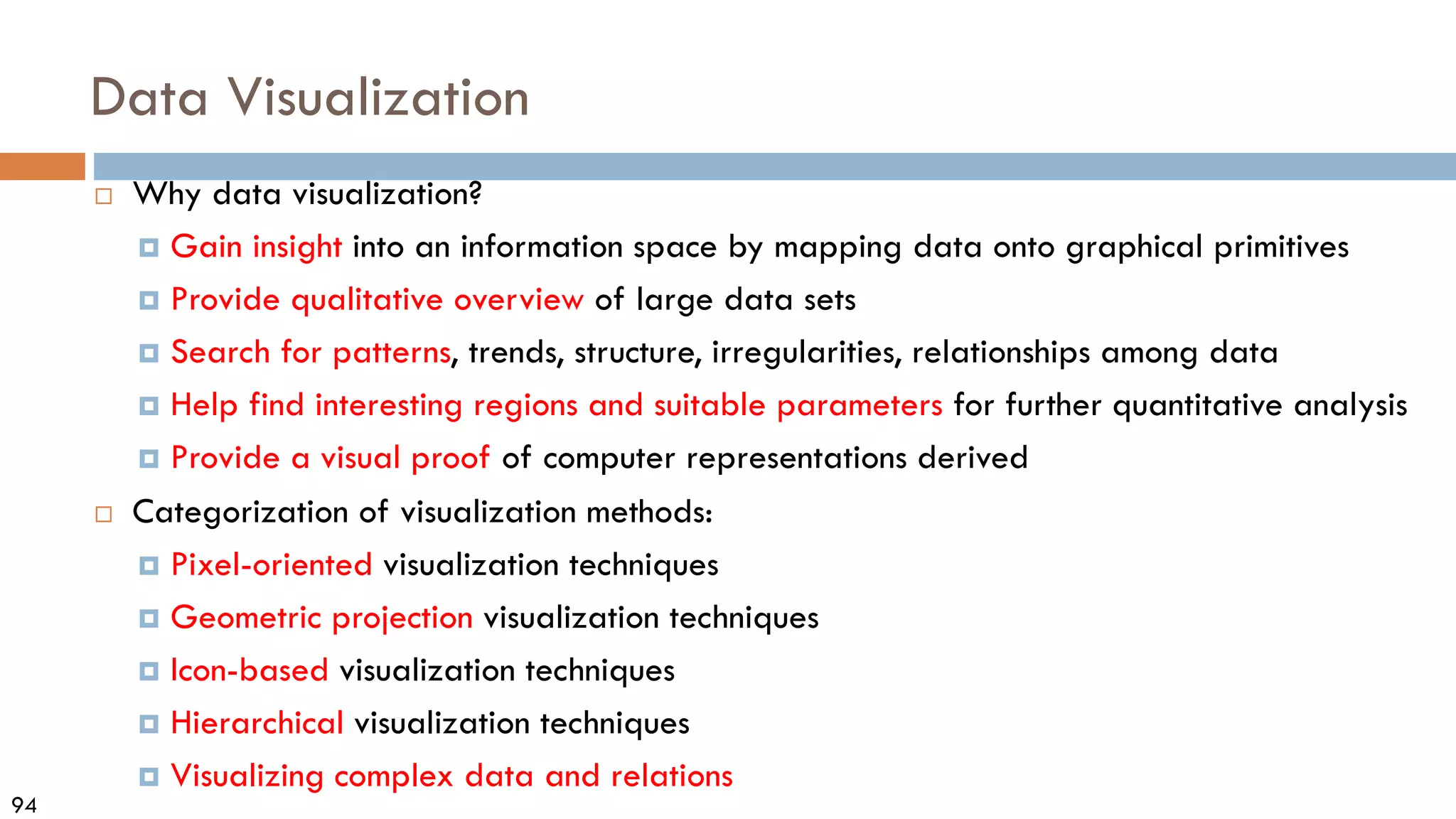

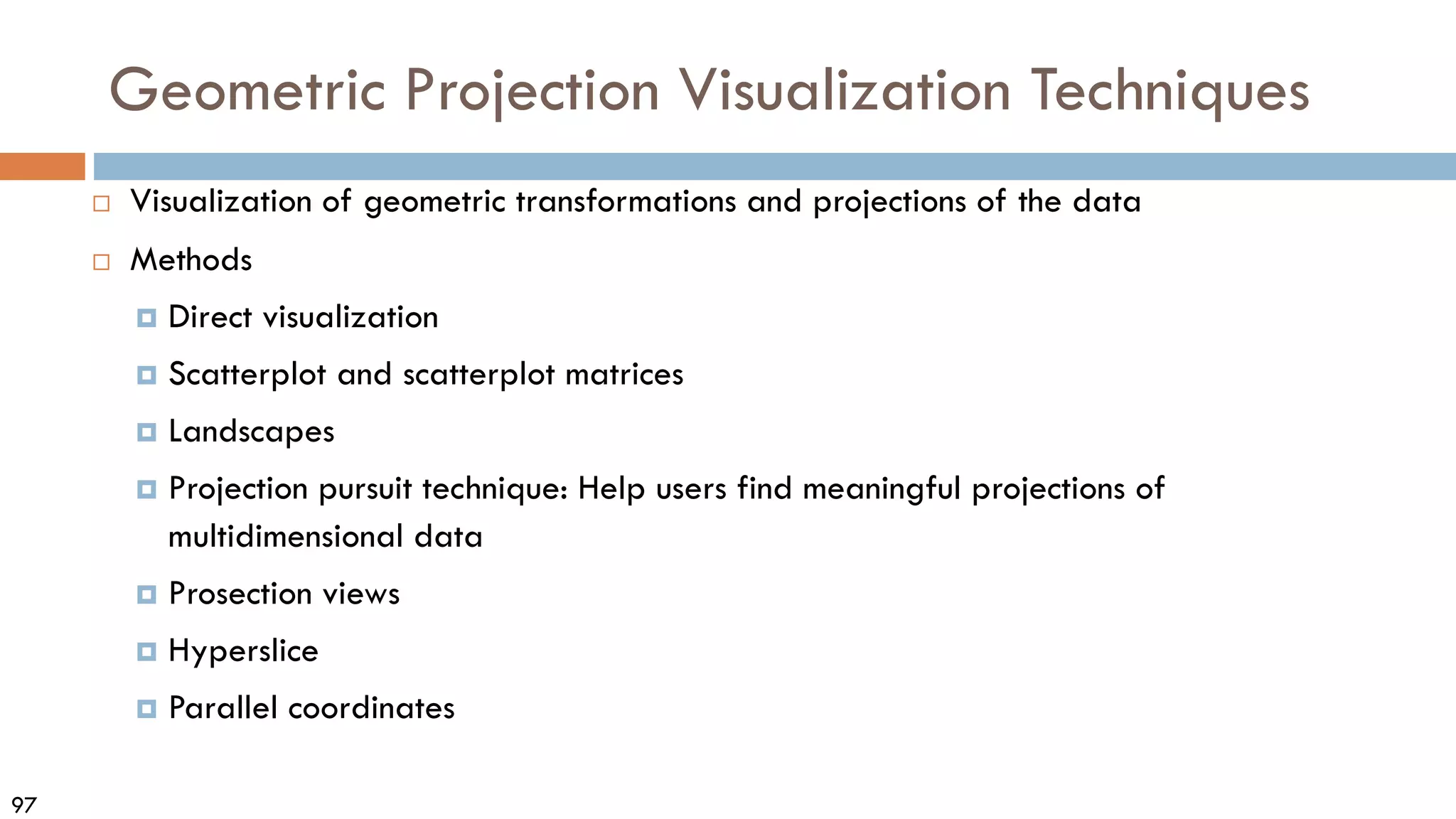

![99

Scatterplot Matrices

Matrix of scatterplots (x-y-

diagrams) of the k-dim. data

[total of (k2/2 ─ k) scatterplots]

Used

by

ermission

of

M.

Ward,

Worcester

Polytechnic

Institute](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-98-2048.jpg)

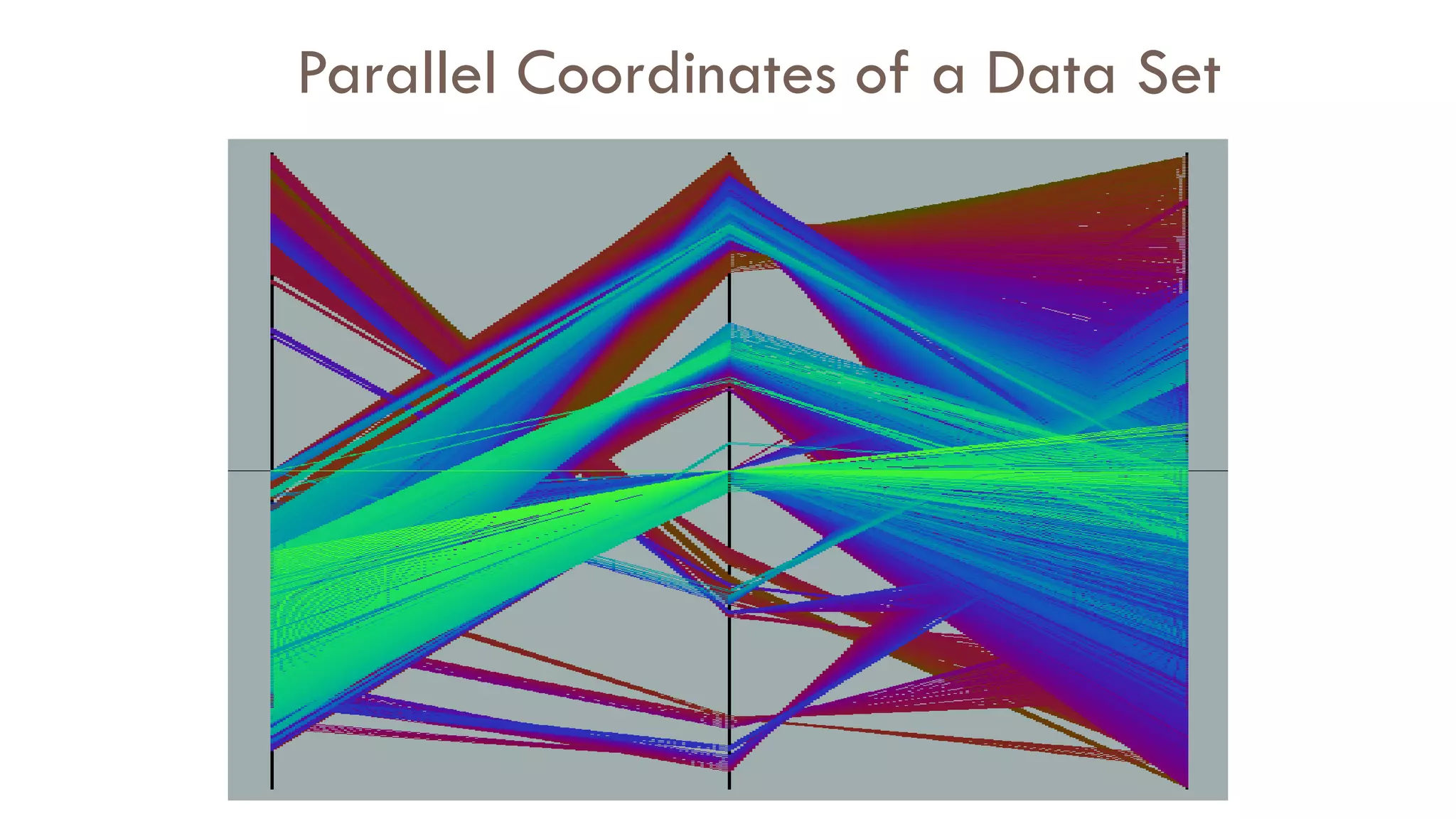

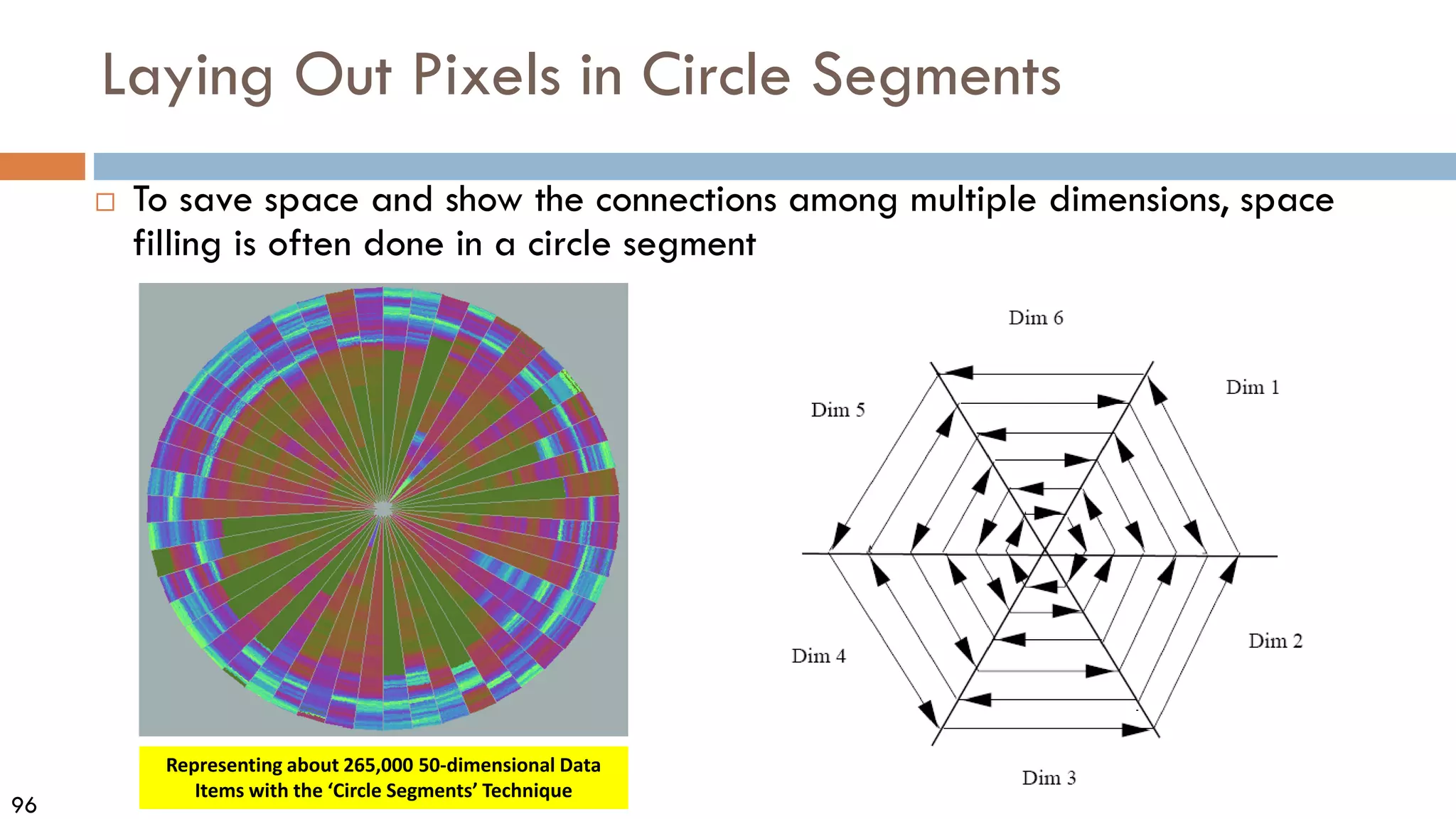

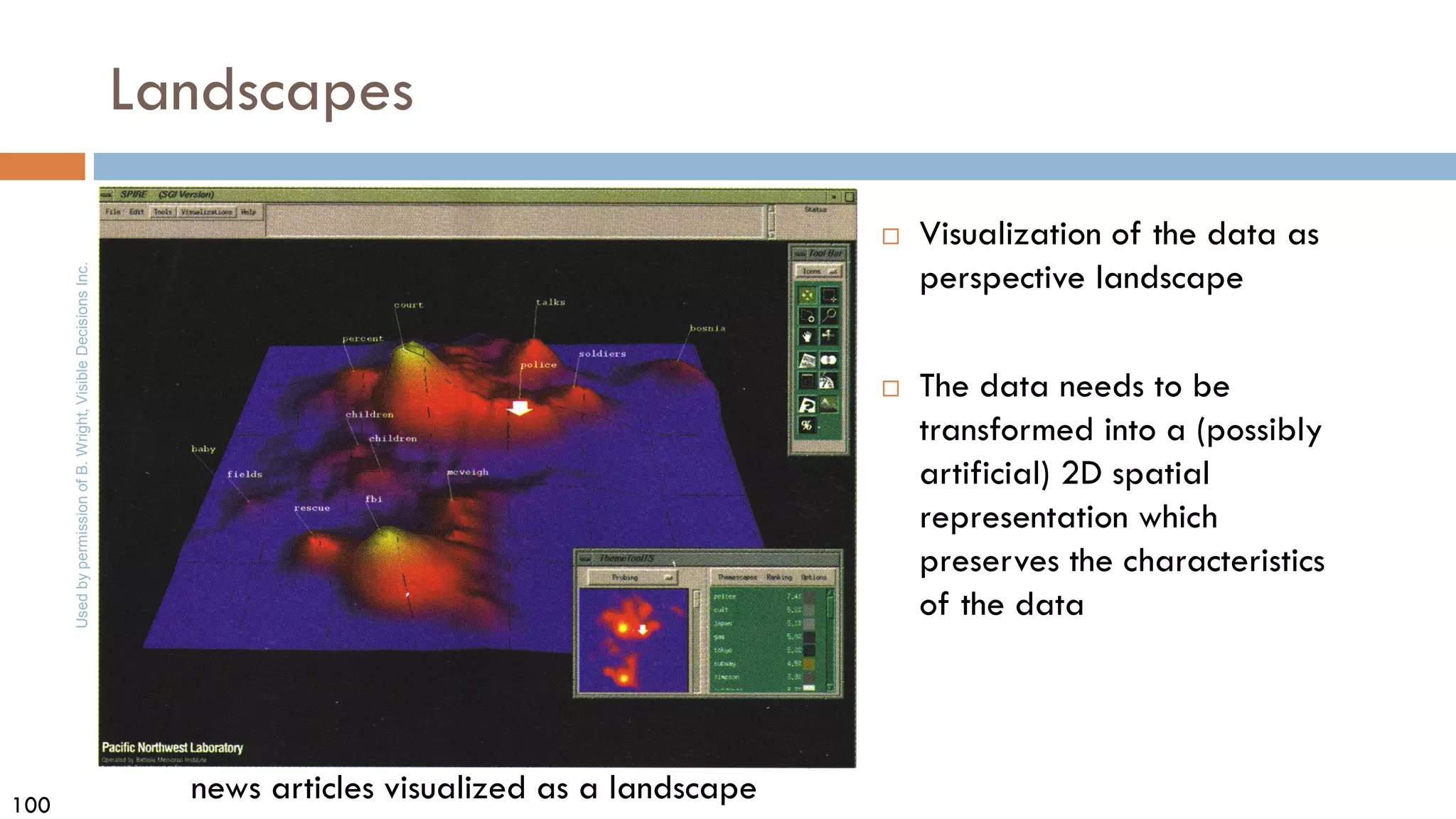

![101

Parallel Coordinates

n equidistant axes which are parallel to

one of the screen axes and correspond

to the attributes

The axes are scaled to the [minimum,

maximum]: range of the corresponding

attribute

Every data item corresponds to a

polygonal line which intersects each of

the axes at the point which corresponds

to the value for the attribute](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02data-osu-0829-230124183437-2a15ff30/75/02Data-osu-0829-pdf-100-2048.jpg)