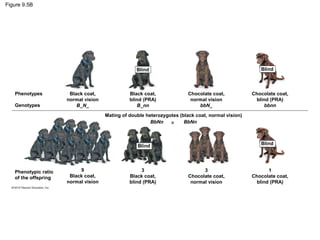

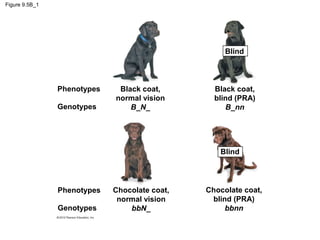

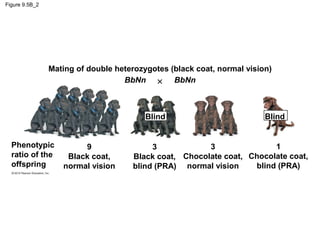

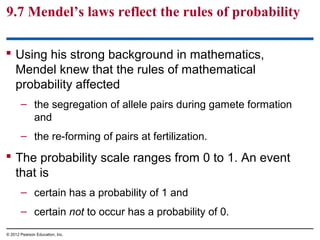

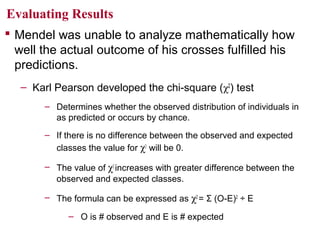

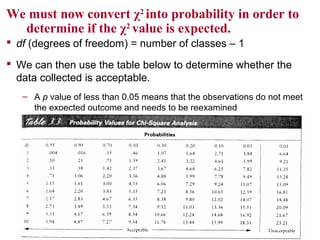

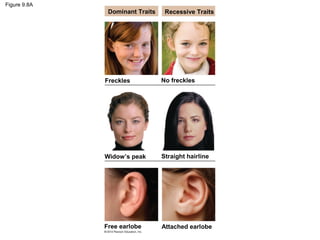

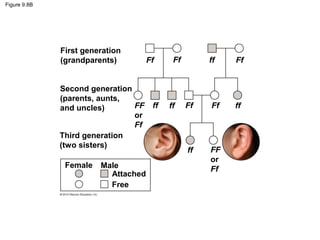

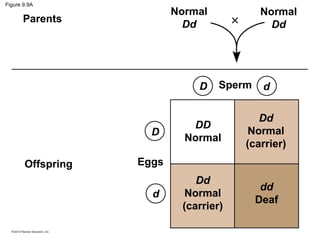

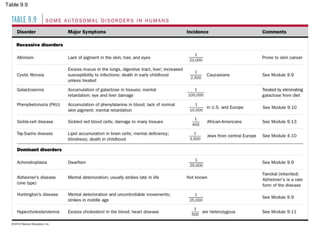

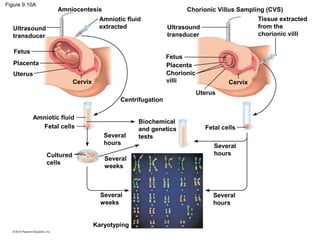

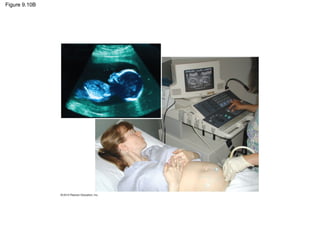

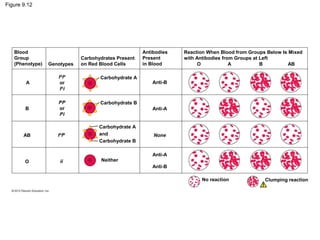

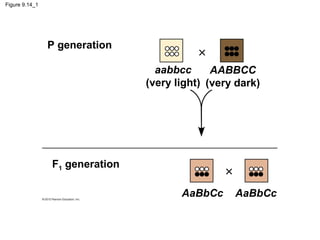

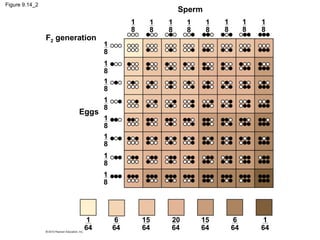

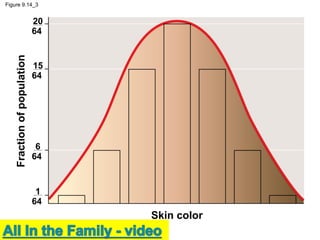

This document summarizes key concepts from Chapter 9 of Campbell Biology: Concepts & Connections regarding patterns of inheritance. It discusses Mendel's laws of inheritance, the chromosomal basis of inheritance, variations on Mendel's laws including independent assortment and multiple alleles. It also covers sex-linked inheritance in humans, inheritance of genetic disorders, genetic testing technologies, and factors influencing complex traits such as polygenic inheritance and gene-environment interactions. Diagrams and examples involving inheritance patterns in humans and model organisms are provided.