- Tuberculosis is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and usually affects the lungs. It spreads through the airborne transmission of droplet nuclei produced by infected individuals.

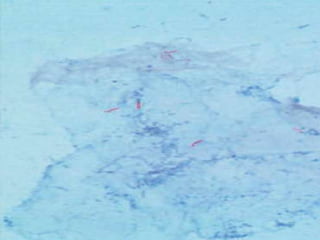

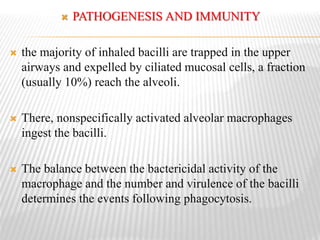

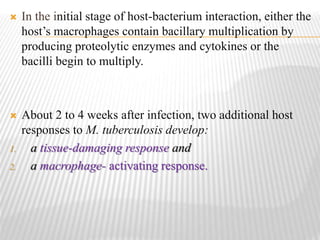

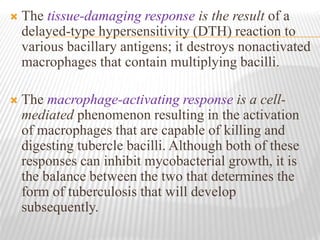

- M. tuberculosis bacteria are rod-shaped, acid-fast bacilli that are ingested by alveolar macrophages in the lungs after inhalation. This begins an infection that may develop into active or latent tuberculosis depending on the immune response.

- Active tuberculosis may be primary, occurring after initial infection, or post-primary, occurring from reactivation of dormant bacteria. It often involves the upper lungs and can cause cavitary lesions and pneumonia if untreated.