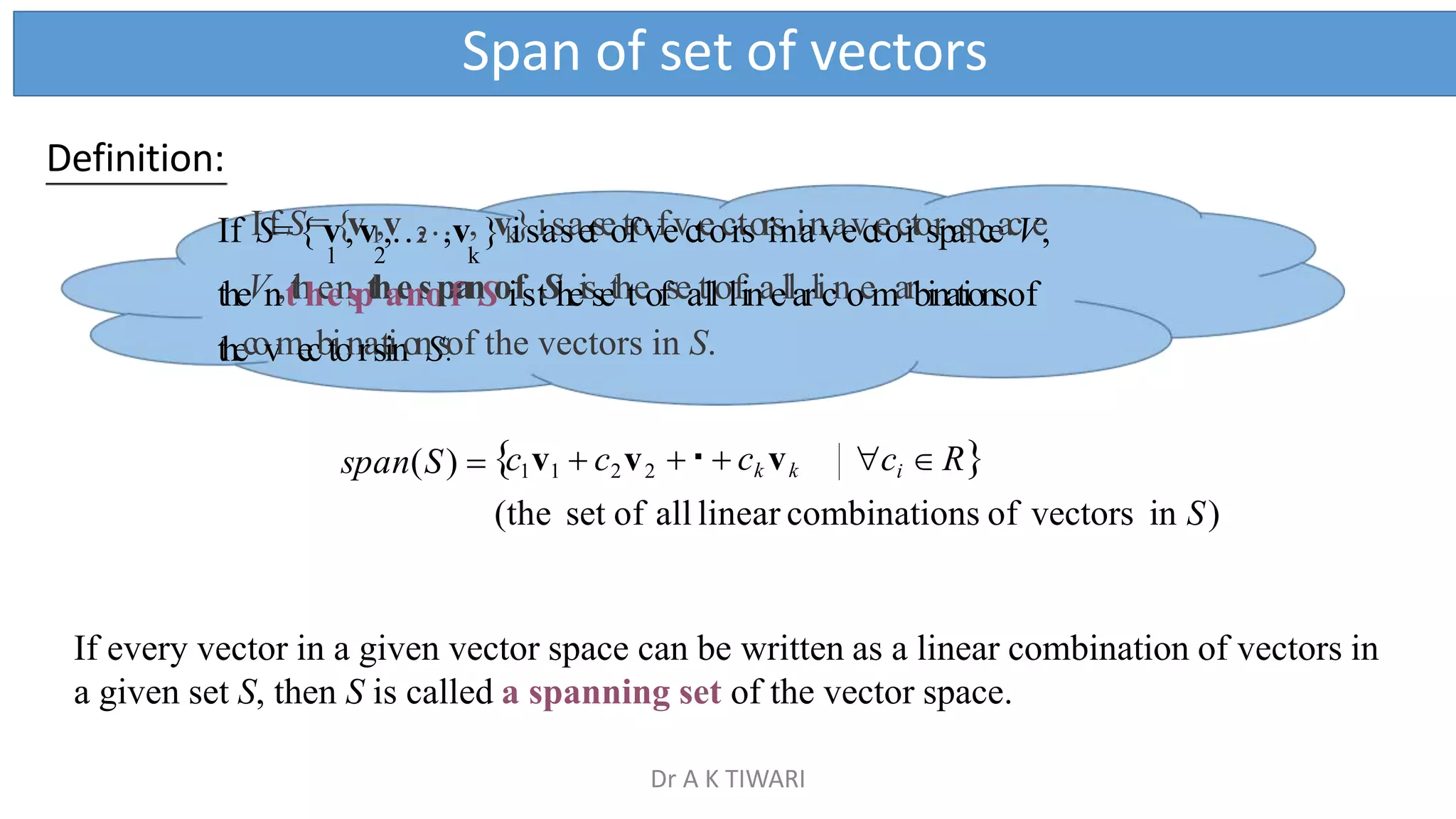

The document discusses vector spaces and related concepts. It begins by defining a vector space as a non-empty set V with defined operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication that satisfy certain axioms. Examples of vector spaces include Rn and the set of m×n matrices. A subspace is a subset of a vector space that is also a vector space under the defined operations. Properties of subspaces and examples are provided. Linear combinations, linear independence, spanning sets, and the span of a set of vectors are then defined and explained.

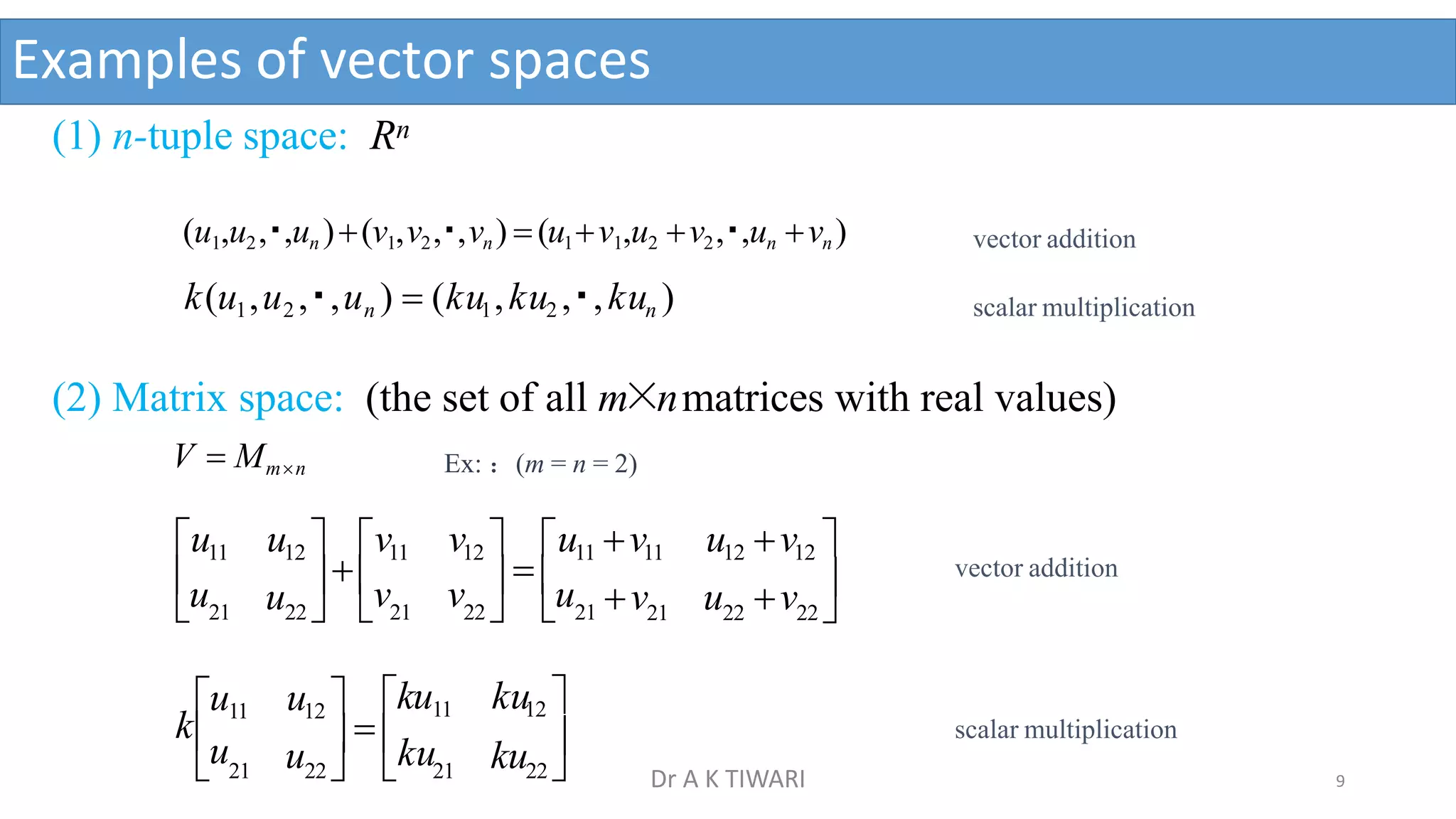

![

m

mn

A

A

a

A

⁝

a

⁝

⁝

a

⁝

m2

a a 2

A1

m1

2n

21 22

a1n

a11 a12

a 21 22 2n (2)

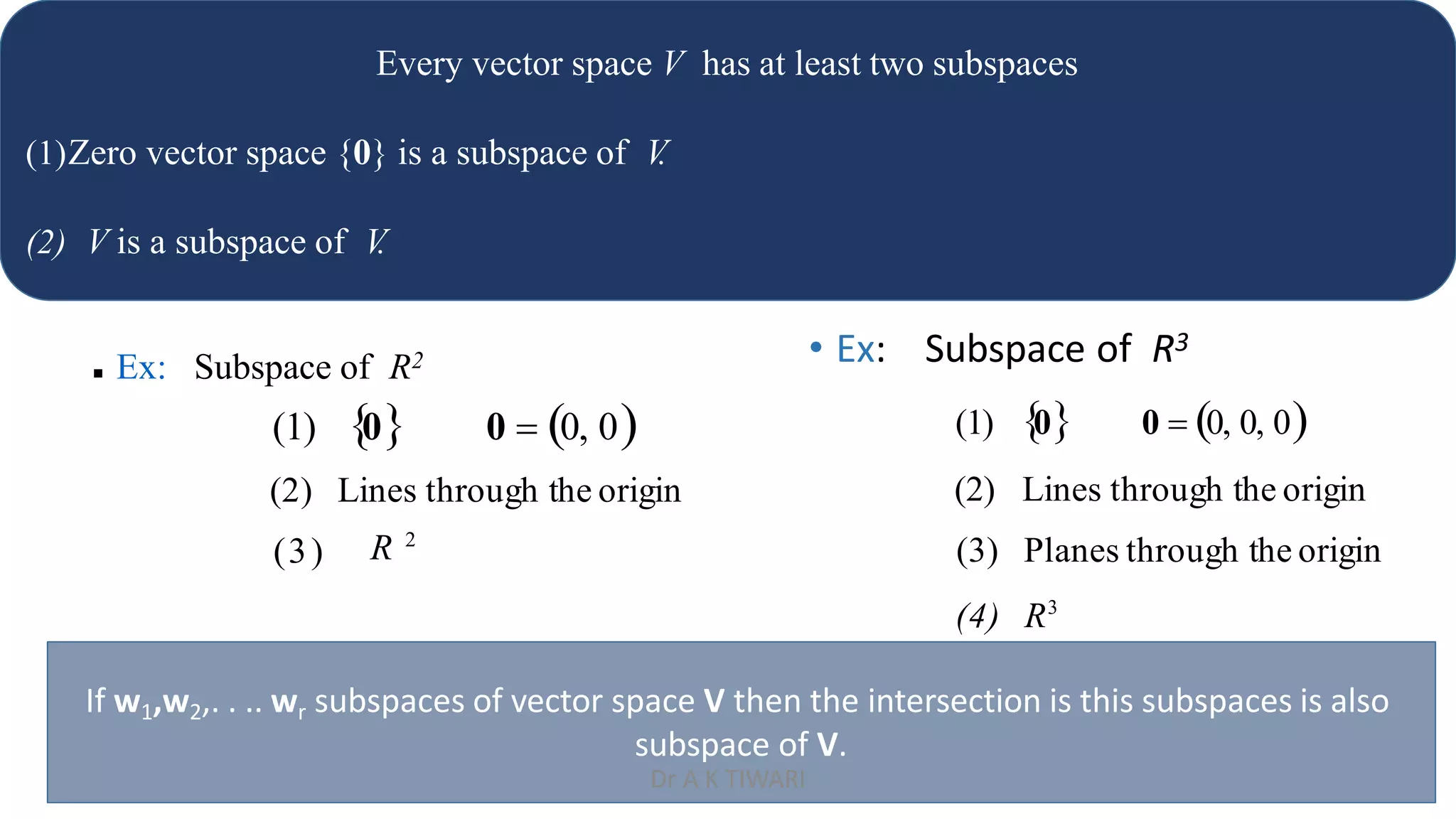

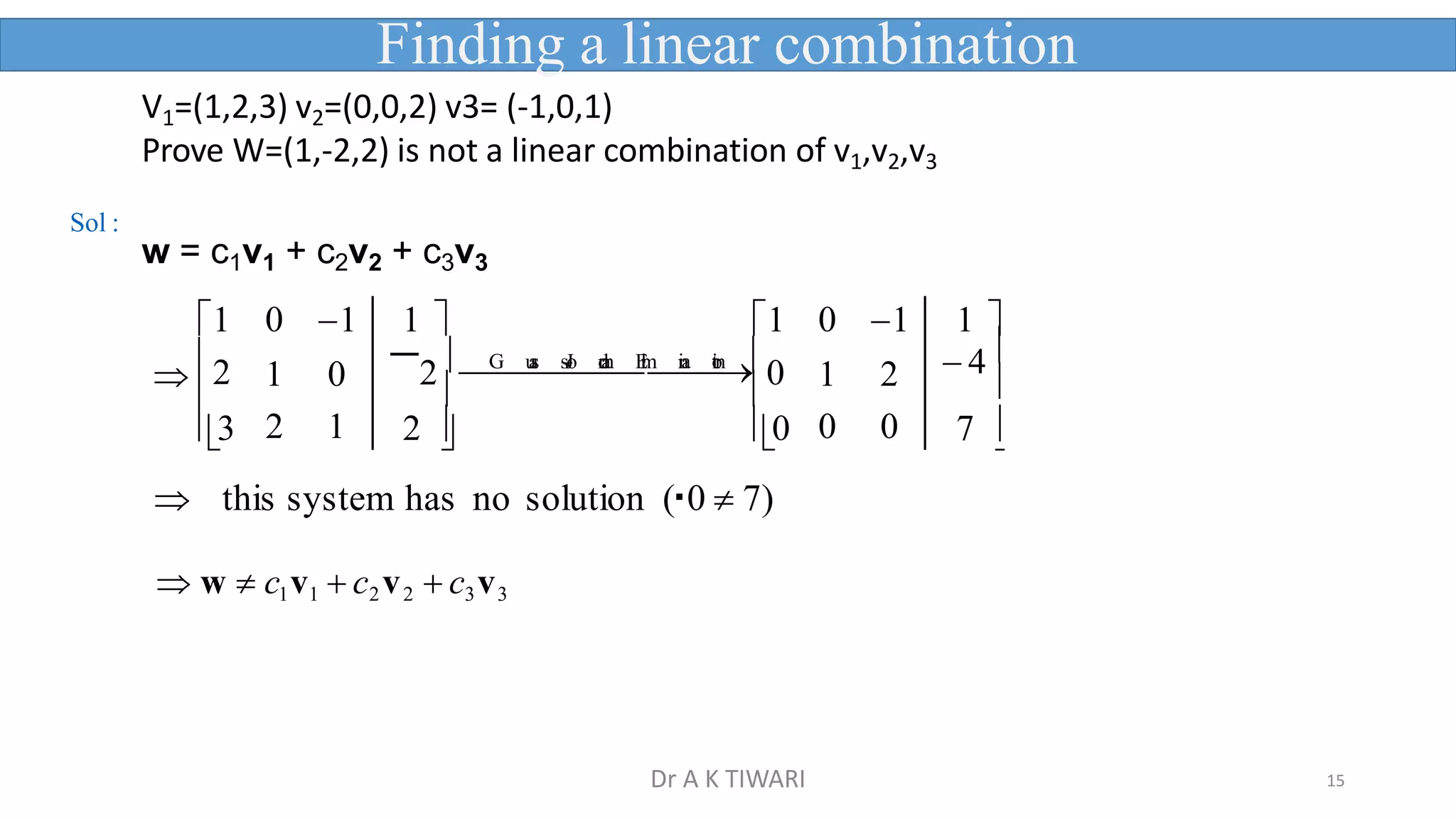

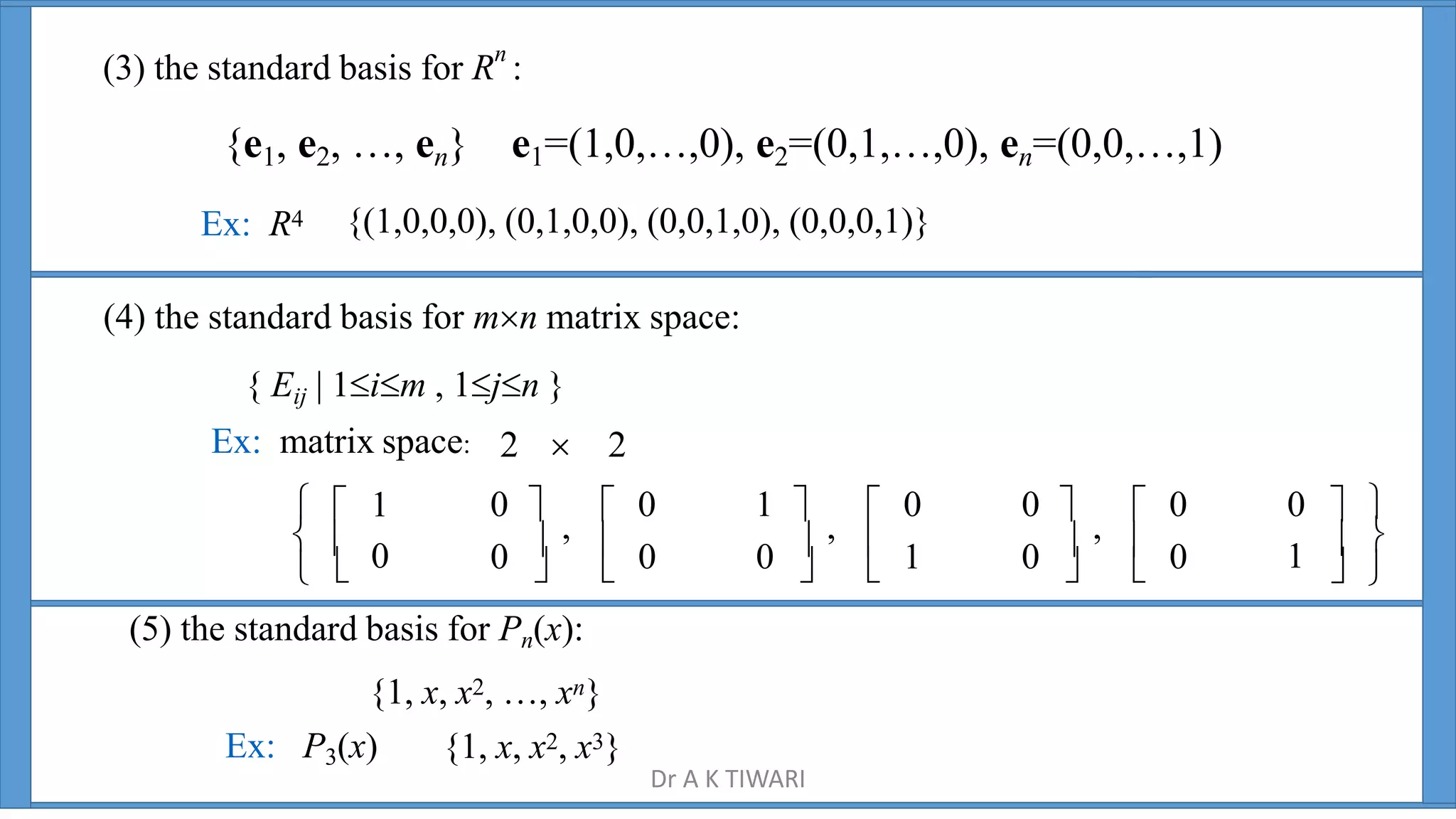

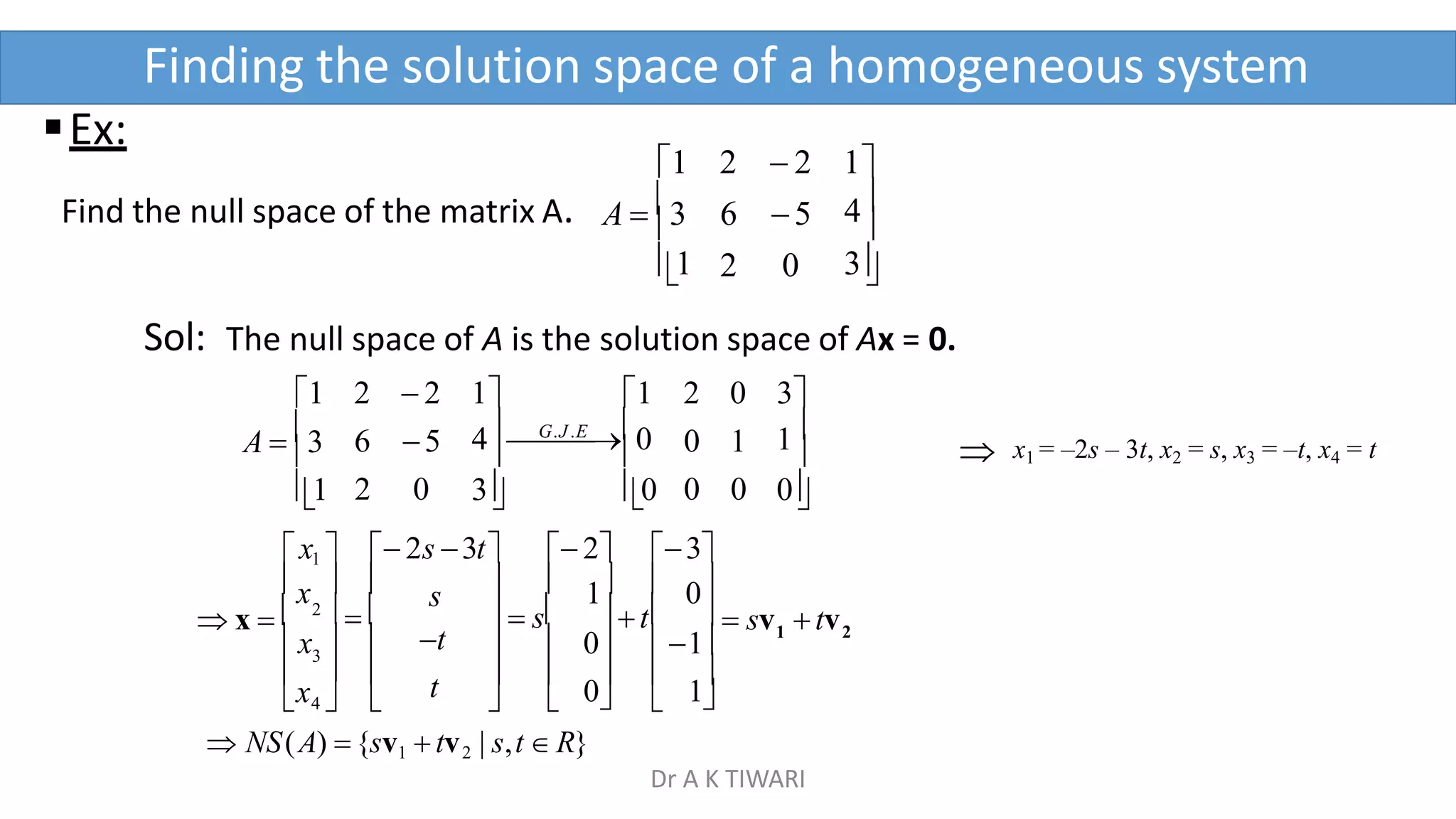

Row vectors of A

[a , a ,…, a ] A

11 12 1n (1)

[a , a ,…, a ] A

⁝

[a , a ,…, a ] A

m1 m2 mn (n)

Column vectors of A

Row Vectors:

1 2 n

A ⁝A ⁝ ⁝A

a a

⁝

am2

2n

22

21

⁝

amn

a1n

⁝

am1

a11 a12

a

A

mn

a a a

⁝ ⁝ ⁝

m1 m2

a a a

21 22 2n

a11 a12 a1n

Column Vectors:

|| ||

A

(1)

A

(2)

||

A

(n)

Dr A K TIWARI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vectorspace-230520021922-e87be485/75/Vector-Space-pptx-33-2048.jpg)

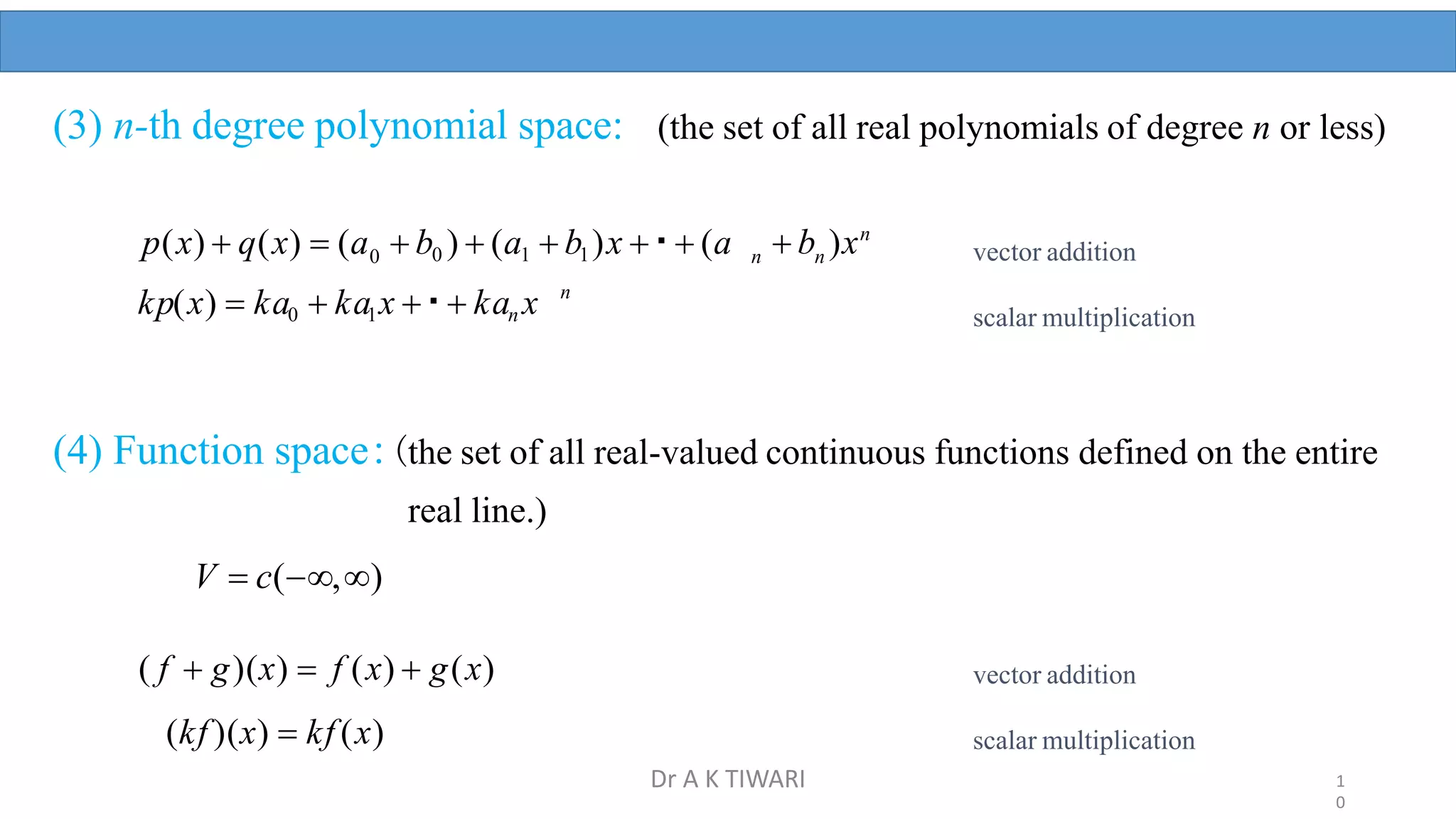

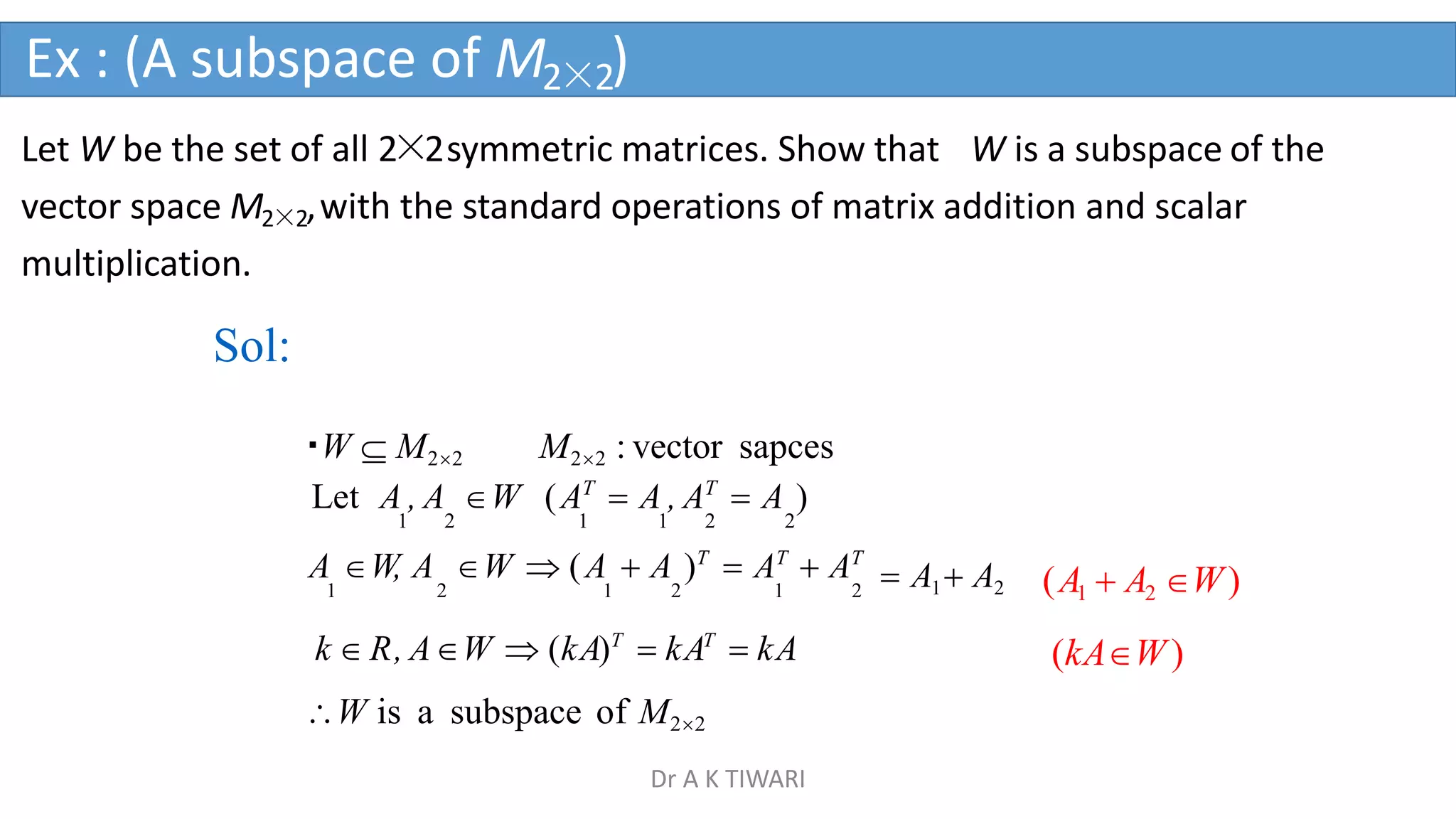

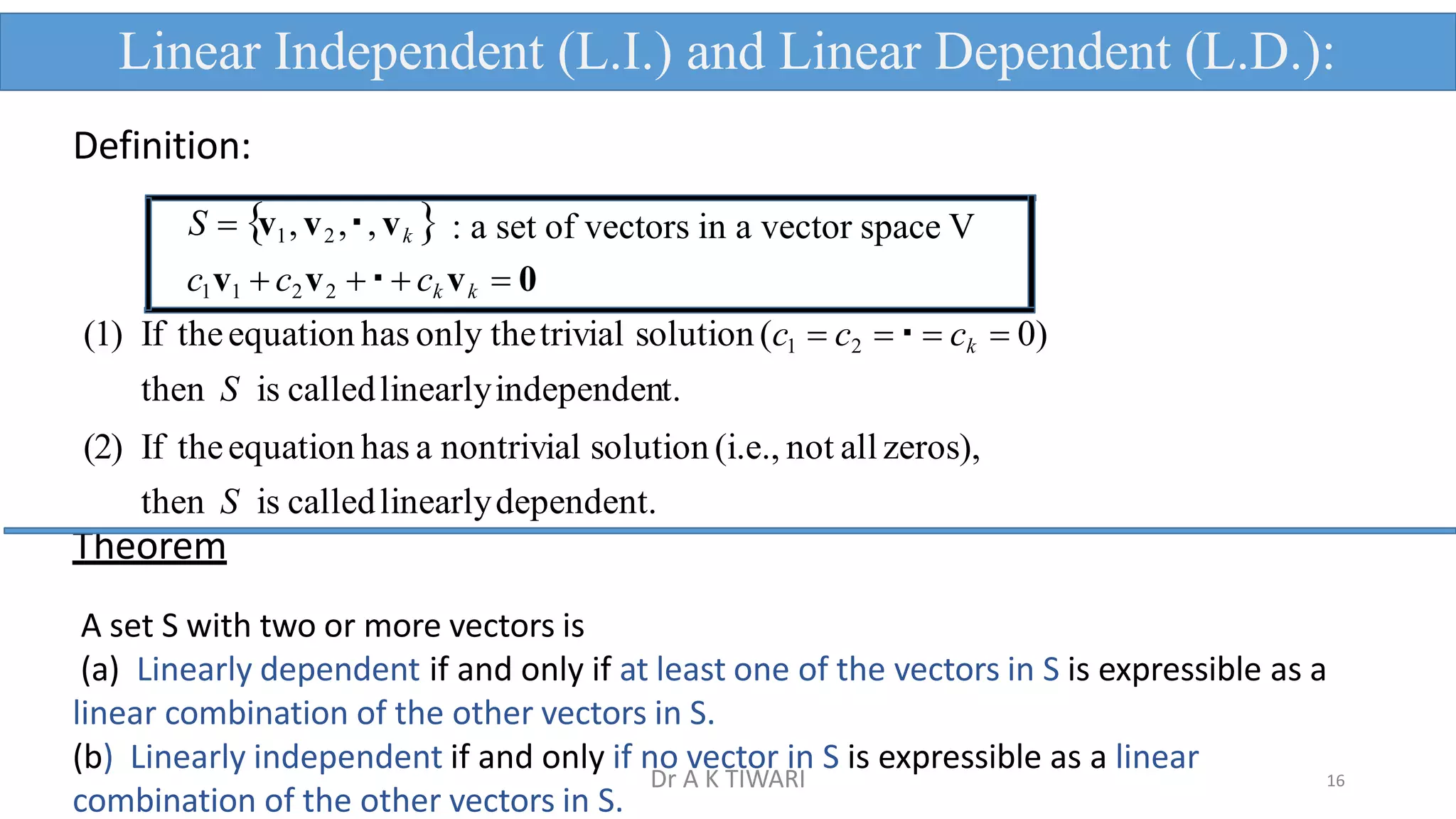

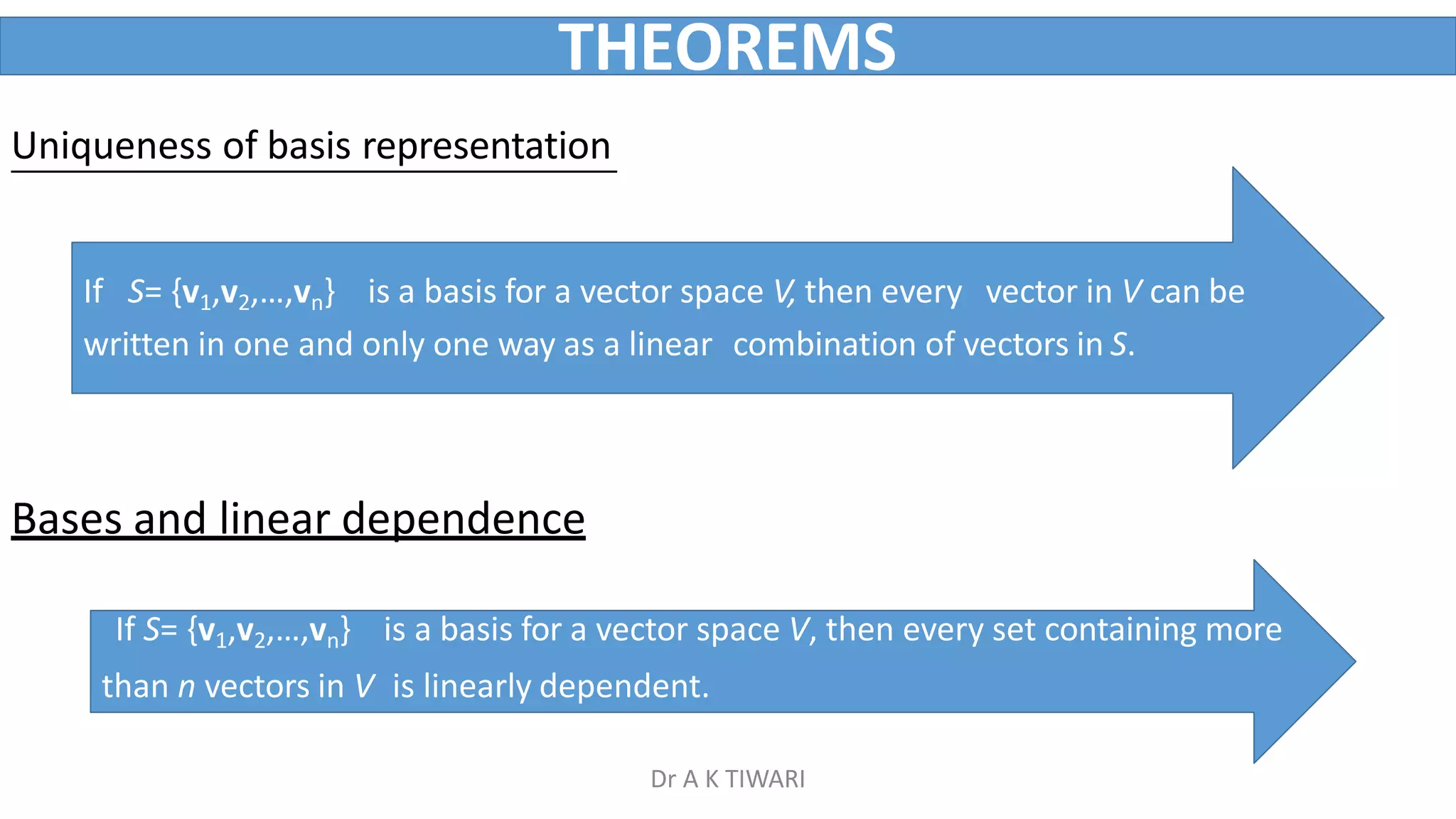

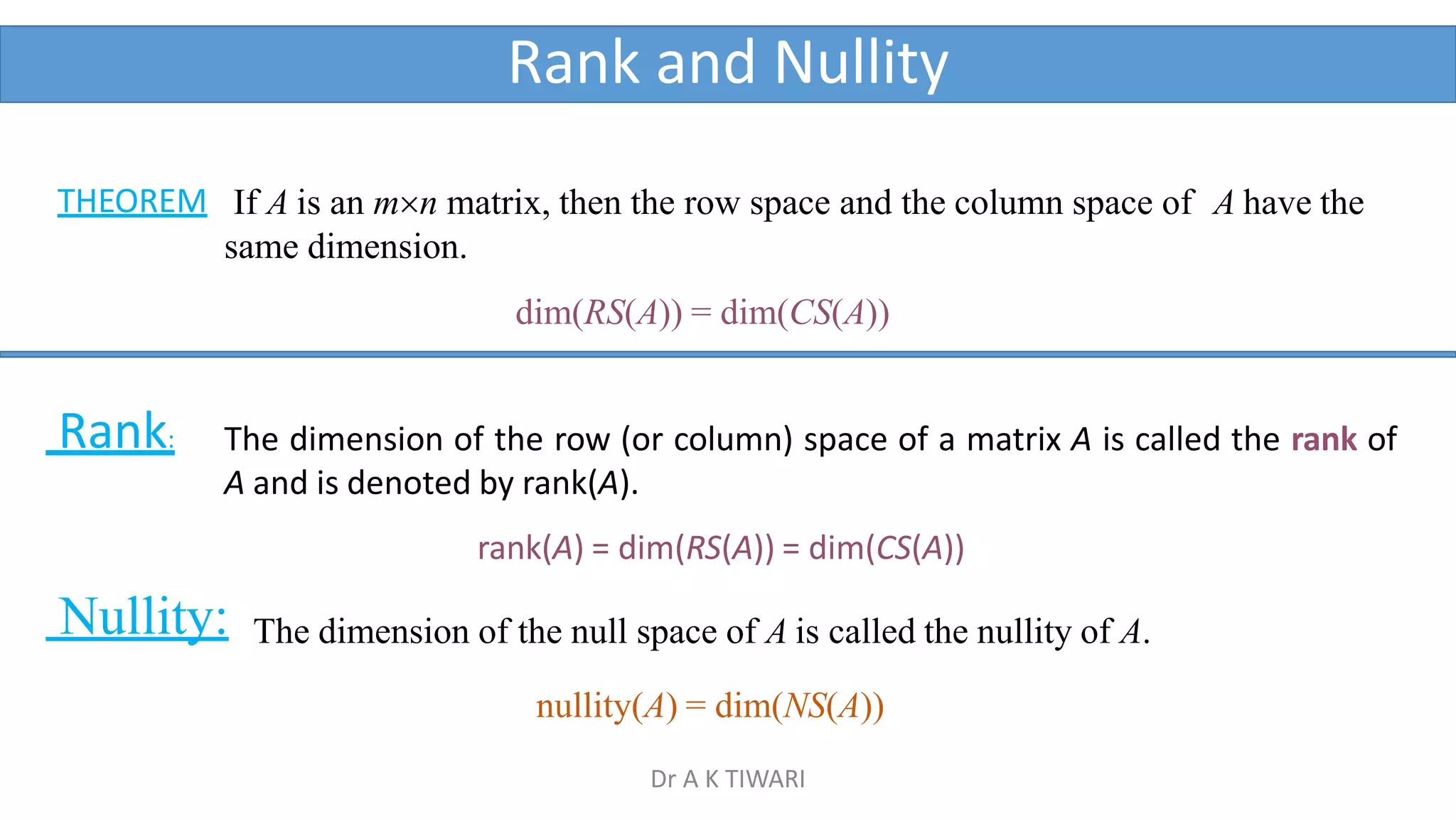

![Find the coordinate matrix of x=(1, 2, –1) in R3 relative to the (nonstandard) basis

B ' = {u1, u2, u3}={(1, 0, 1), (0, – 1, 2), (2, 3, – 5)}

Sol:

x c u c u c u (1, 2, 1) c (1, 0,1) c (0, 1, 2) c (2, 3, 5)

1 1 2 2 3 3 1 2 3

1

0

1

3

2

0

1

5c 1

3c 2

2c 1

3

2

1

c 2c 5c 1

0 2 1 1 0 0 5

1 3 2 G.J

.E.

0 1 0 8

2 5 1 0 0 1 2

c 2c 1 1 0

1 3

c 3c 2 i.e. 1

2 3

1 2

2

5

B

[ x ] 8

Finding a coordinate matrix relative to a nonstandard basis

Dr A K TIWARI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vectorspace-230520021922-e87be485/75/Vector-Space-pptx-44-2048.jpg)

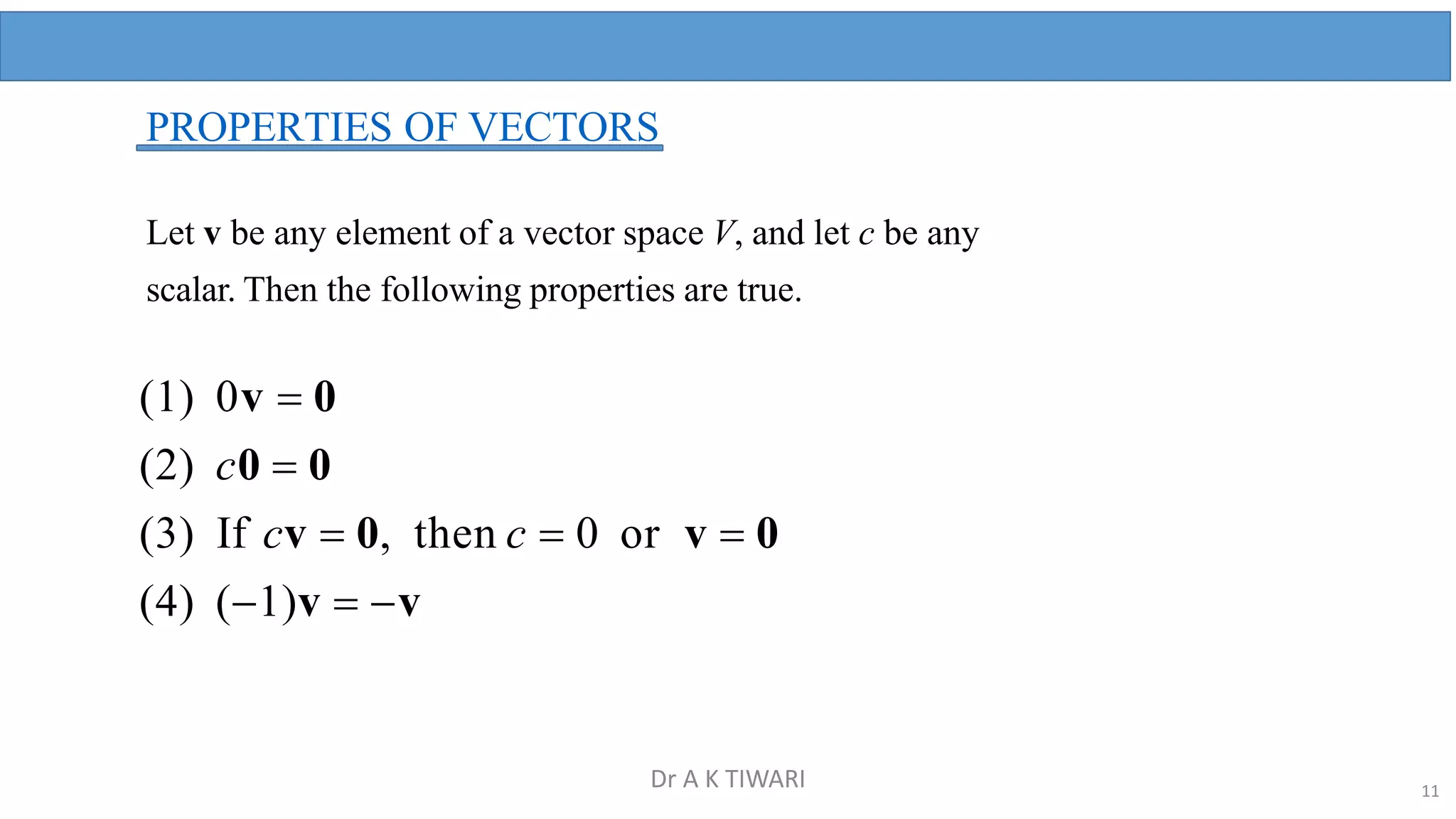

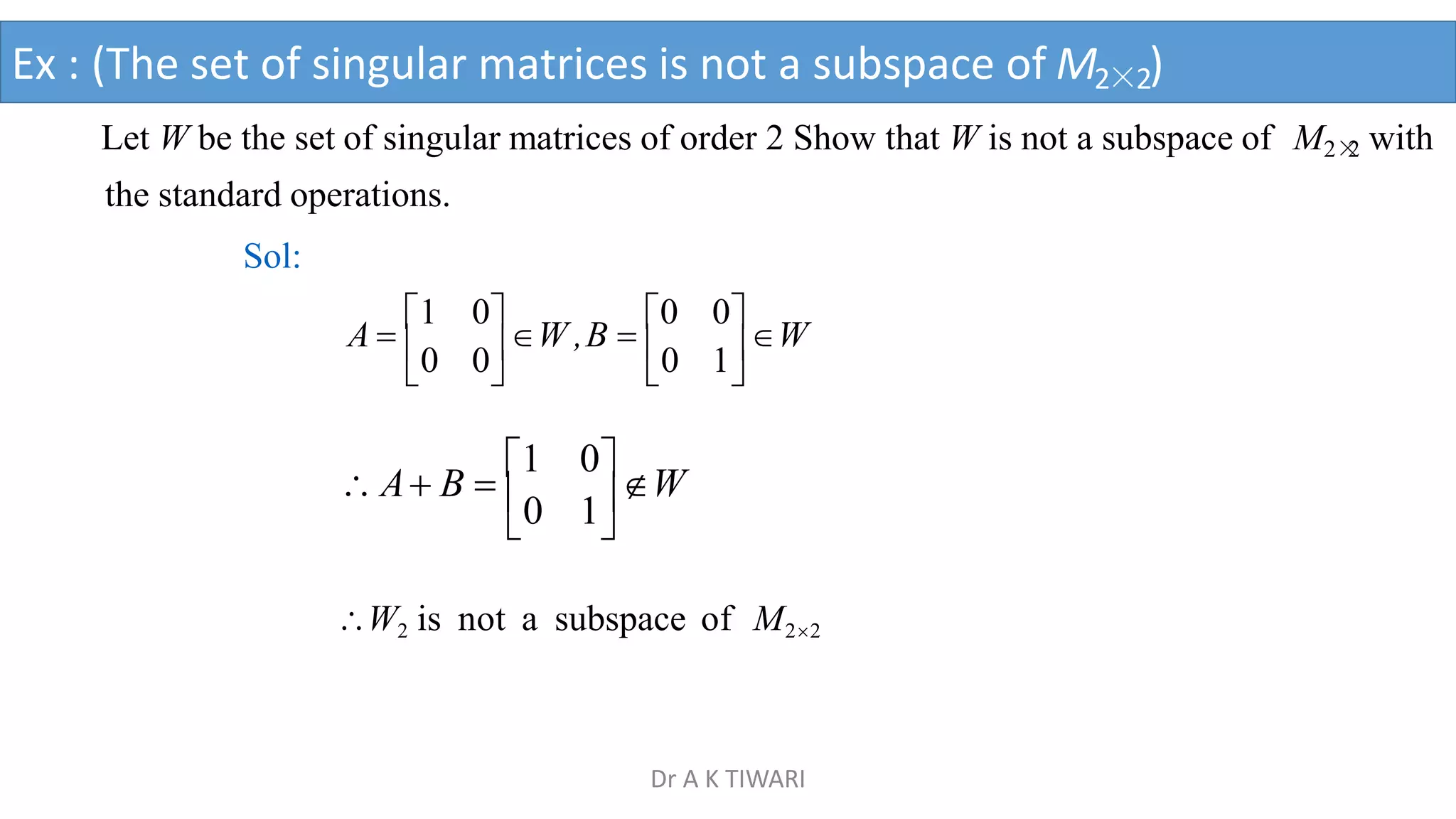

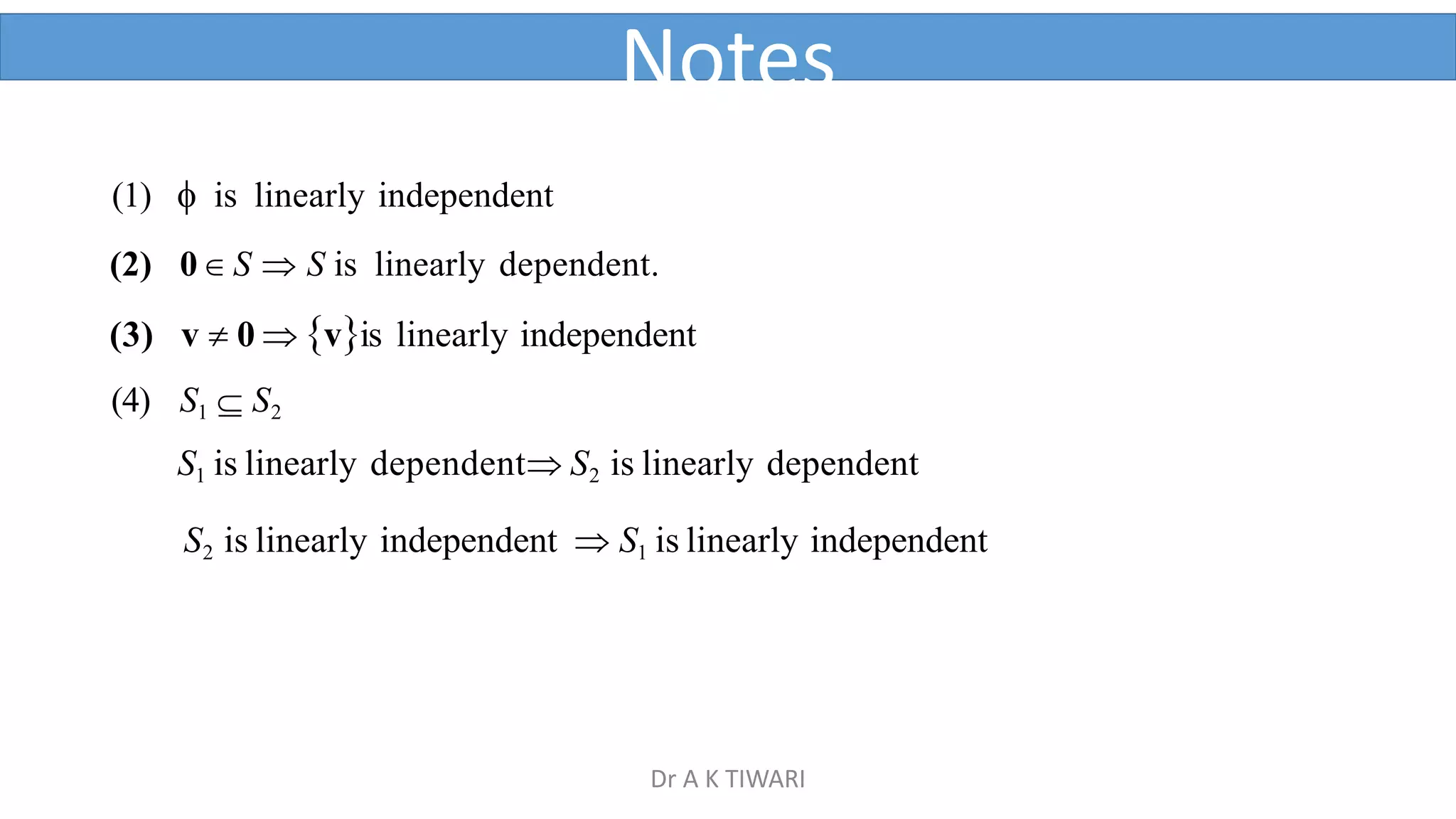

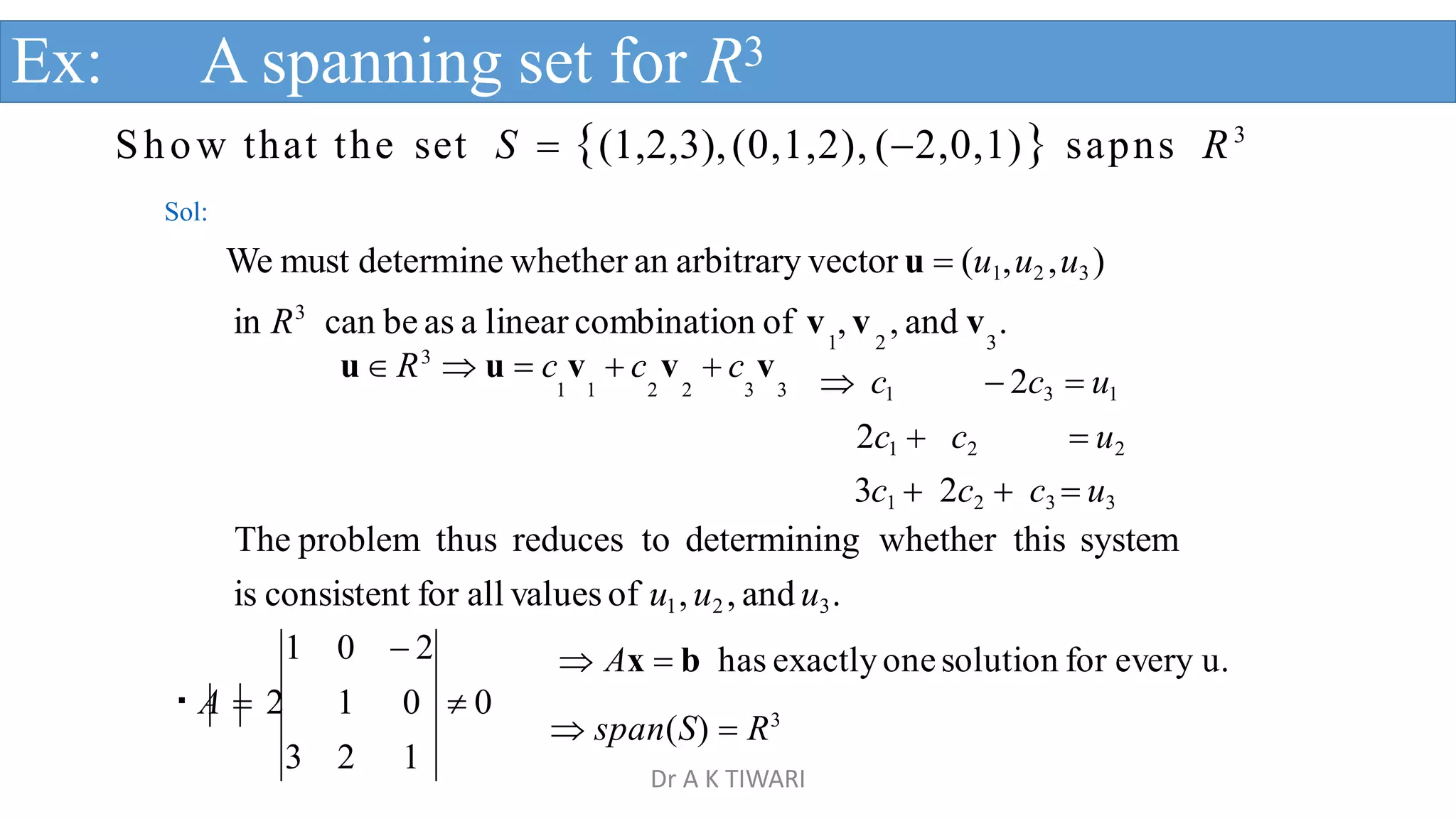

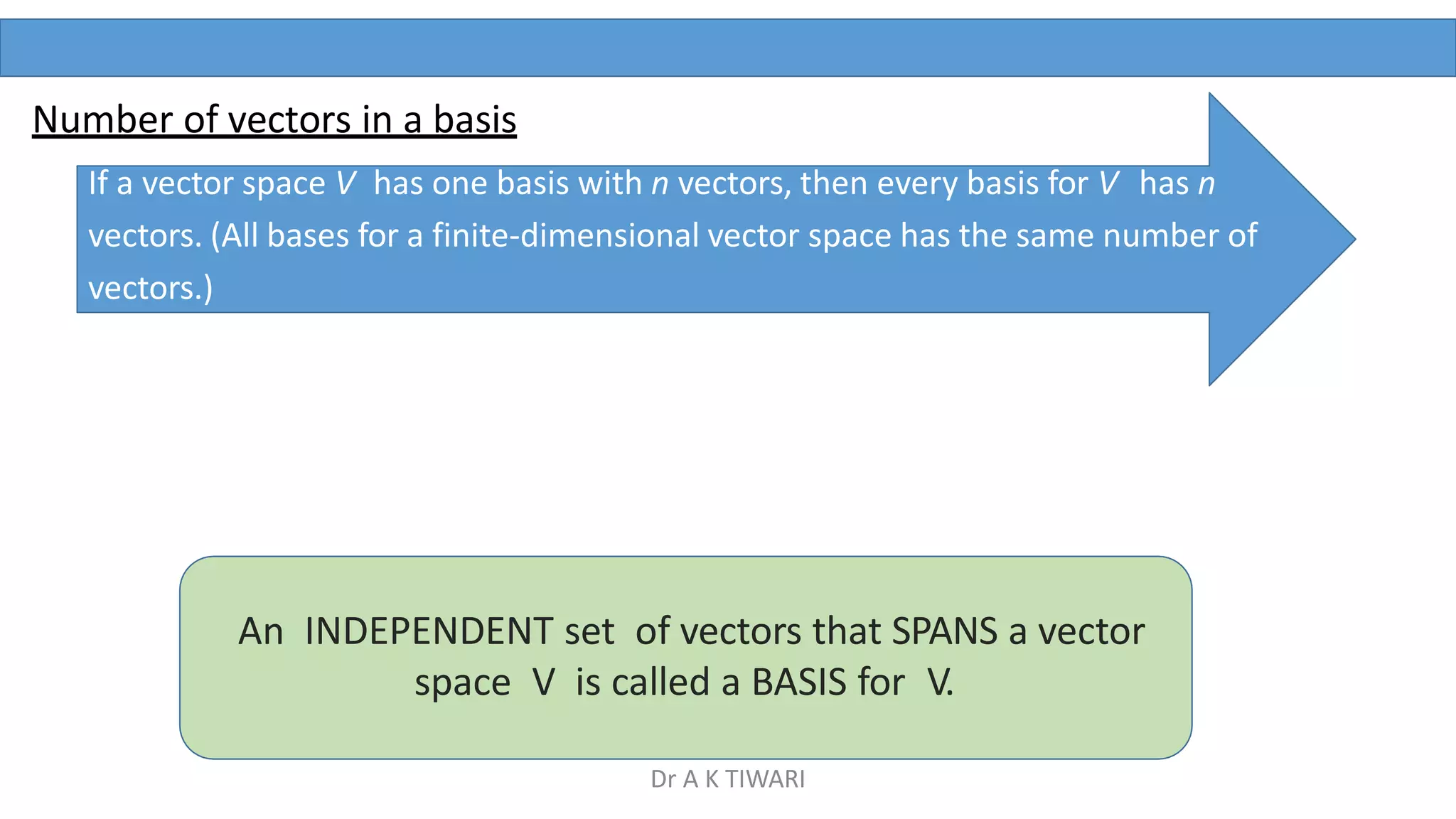

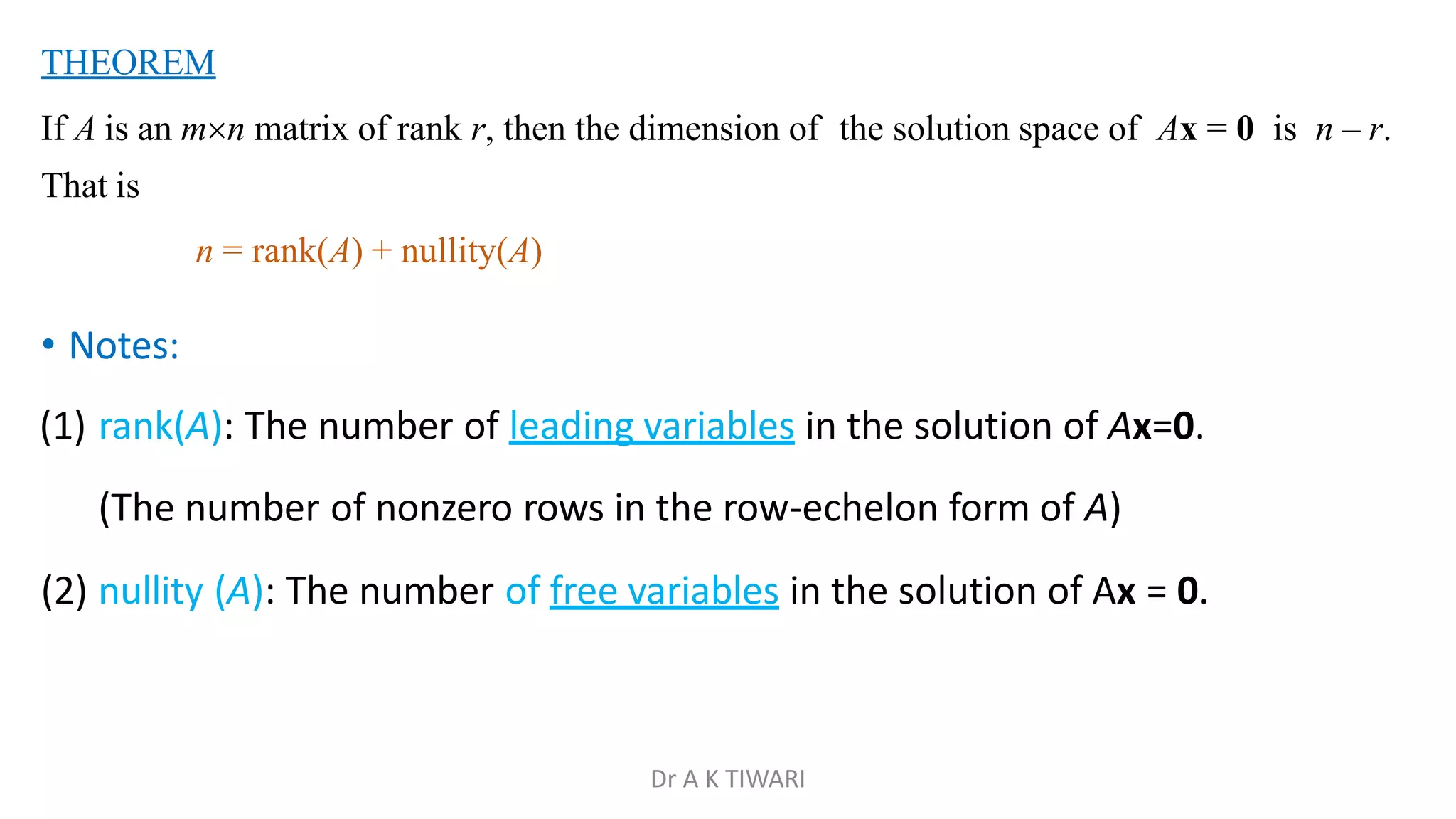

![Change of basis problem

B B B B

1

u

u ,..., v

u , 2 n

then [v]B P[v]B

where

You were given the coordinates of a vector relative to one basis B and were asked to find

the coordinates relative to another basis B'.

Transition matrix from B' to B:

Let B {u1,u2 ,...,un} and B {u1

,u2...,un} be two bases

for a vector space V

If [v]B is the coordinate matrix of v relative to B

[v]B‘ is the coordinate matrix of v relative to B'

n

B B

P u , u ,..., u

1 B 2

is called the transition matrix from B' to B

Dr A K TIWARI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vectorspace-230520021922-e87be485/75/Vector-Space-pptx-45-2048.jpg)

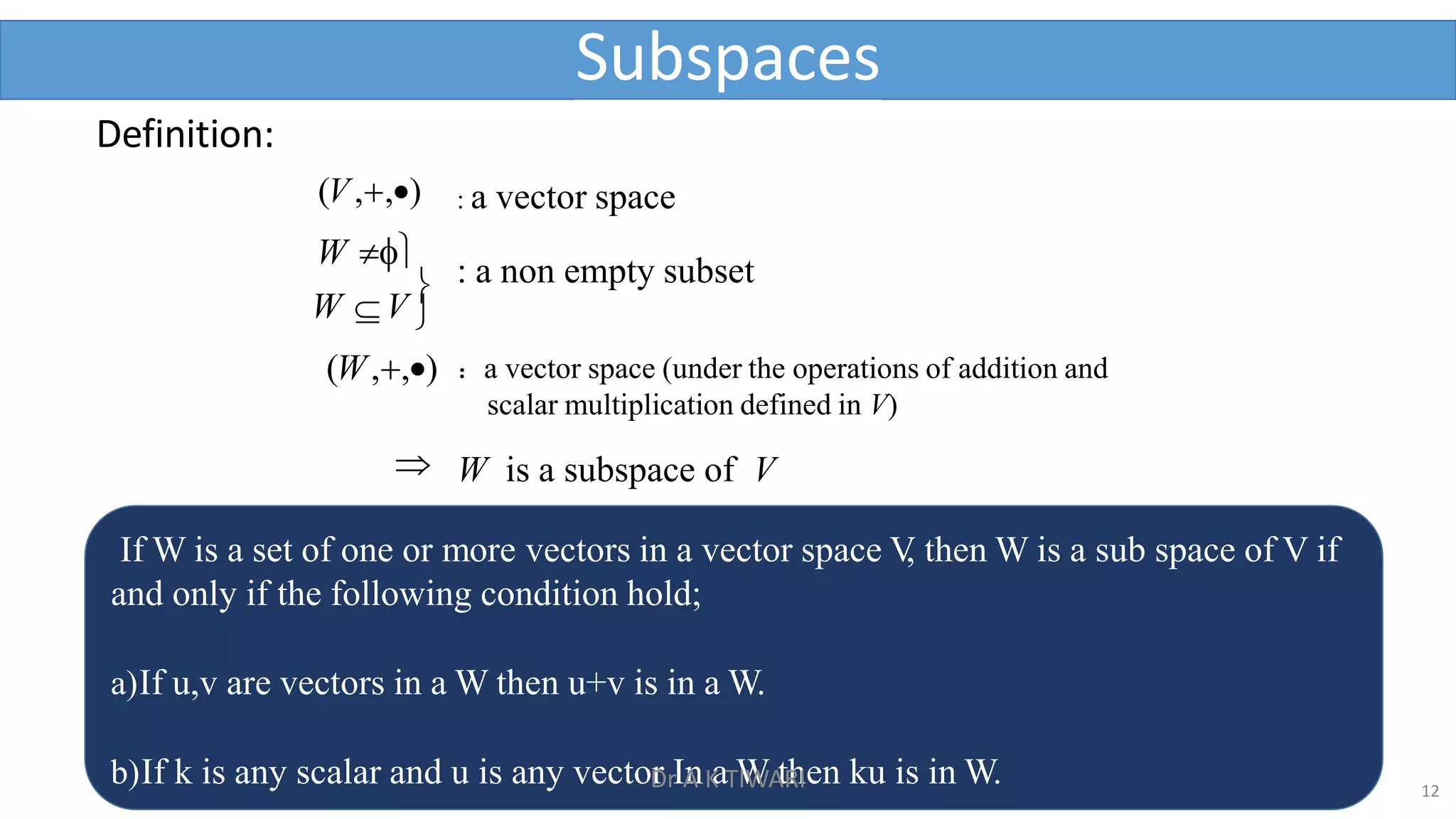

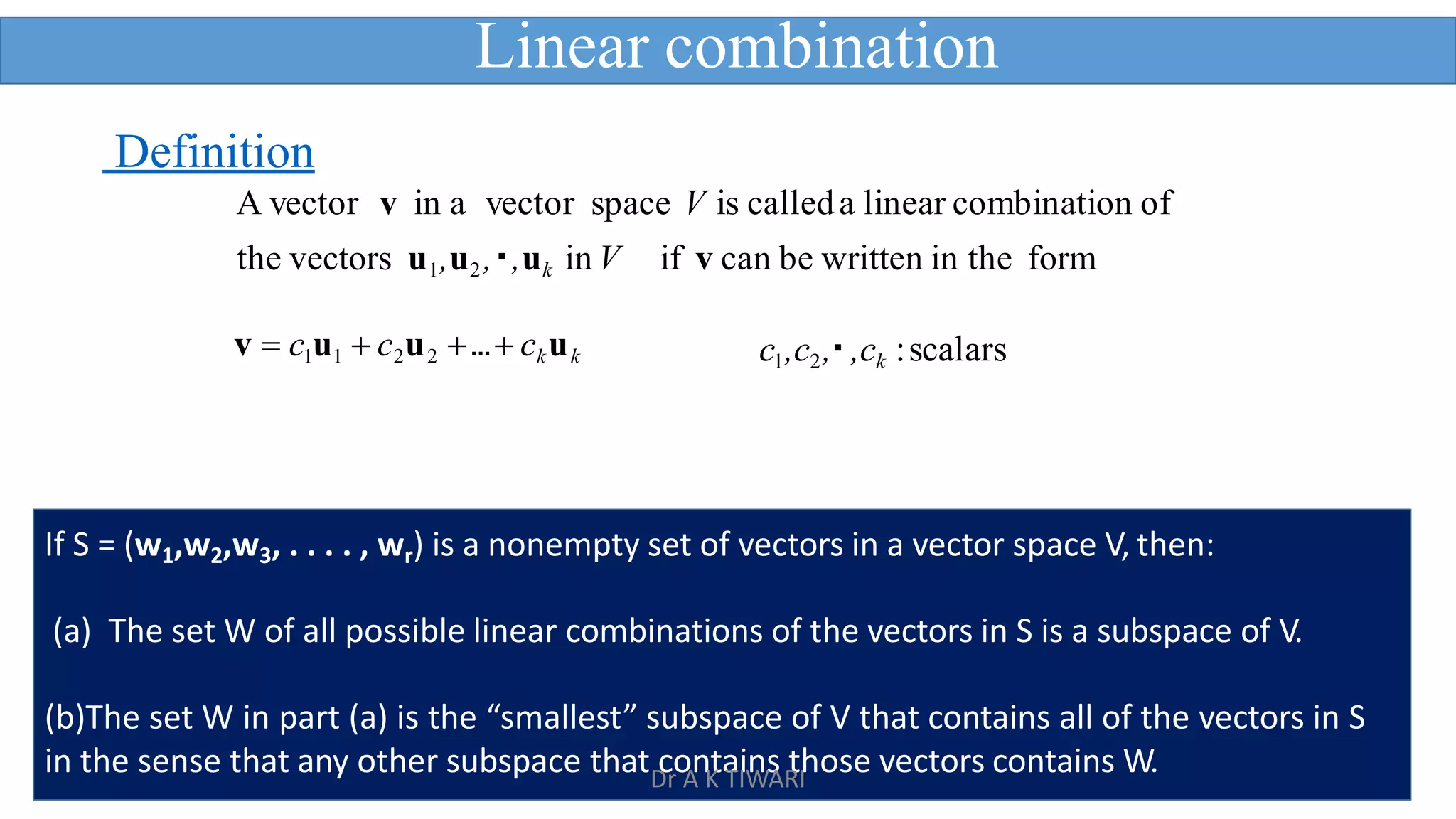

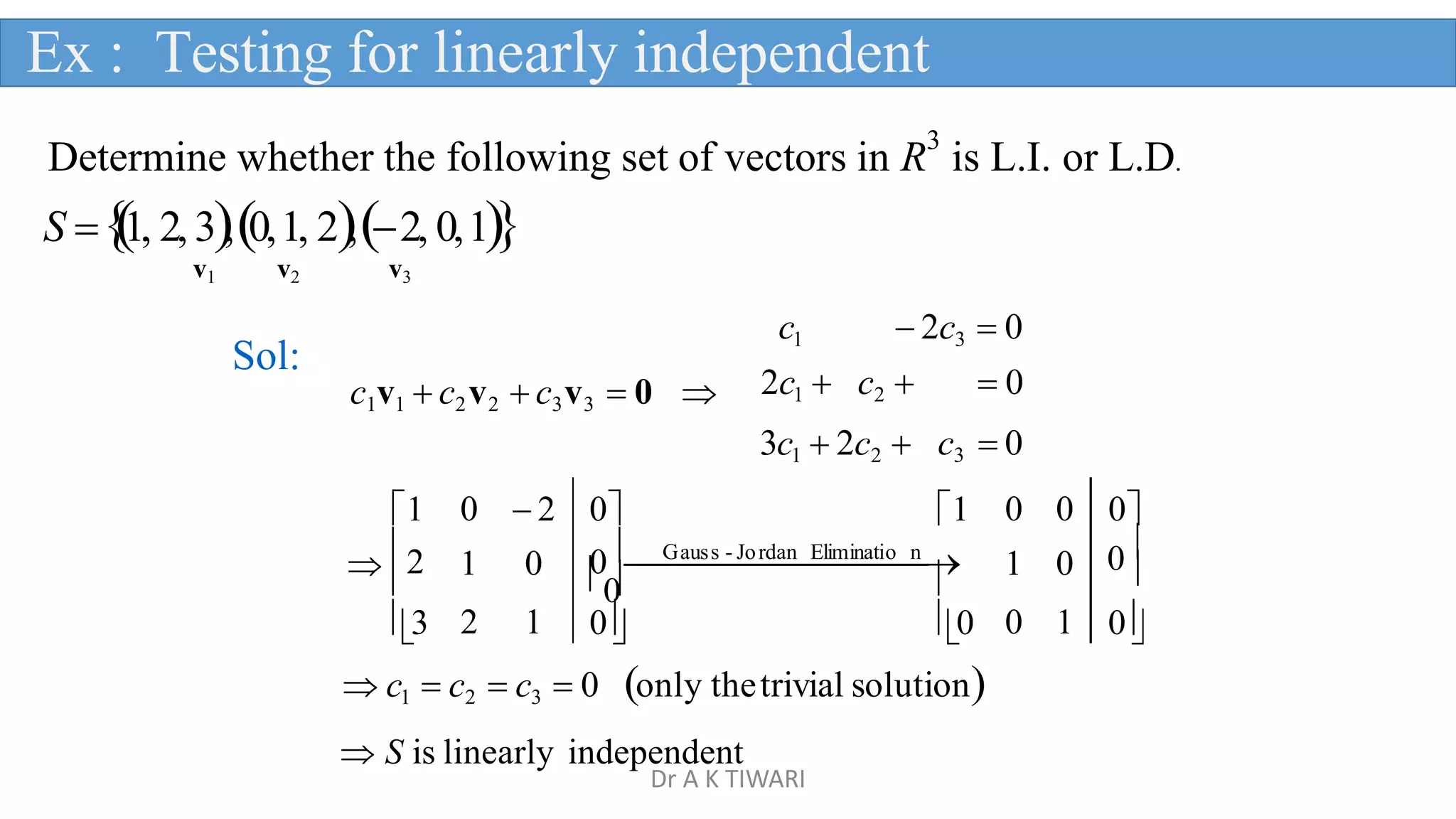

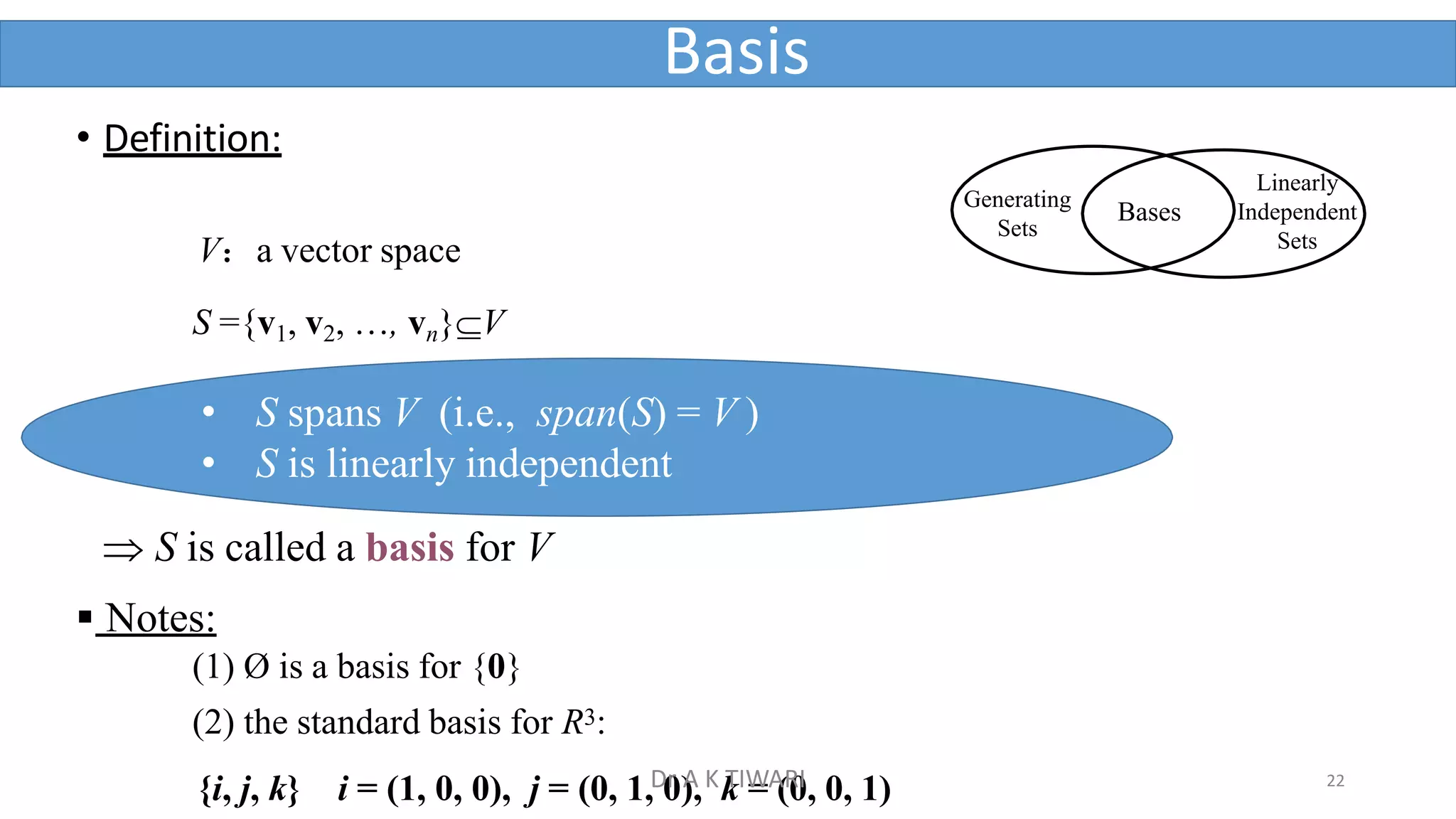

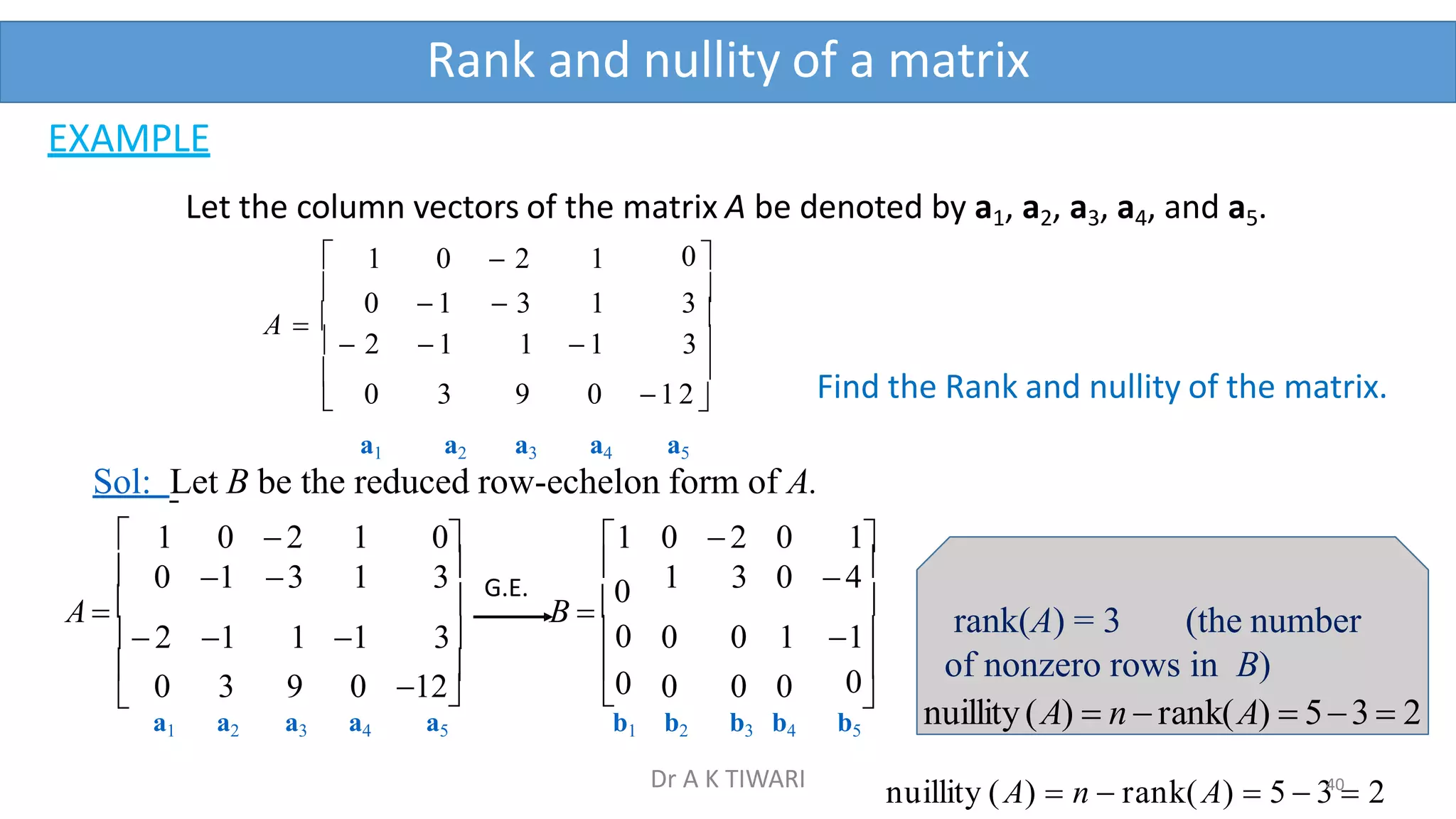

![2

B={(–3, 2), (4,–2)} and B' ={(–1, 2), (2,–2)} are two bases for R

(a) Find the transition matrix from B' to B.

B

B'

(b) Let [v] find [v]

2

1

,

Ex : (Finding a transition matrix)

0

1 0 ⁝ 3 2

I

1 ⁝ 2 1

P

(c) Find the transition matrix from B to B' .

Sol:

2

2

2

2

3

3 4

4 ⁝

⁝

1

1 22

2

2

2

2 ⁝

⁝

B

1

3 2

P 2

(the transition matrix from B' to B)

G.J.E.

B'

(a)

Dr A K TIWARI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vectorspace-230520021922-e87be485/75/Vector-Space-pptx-47-2048.jpg)

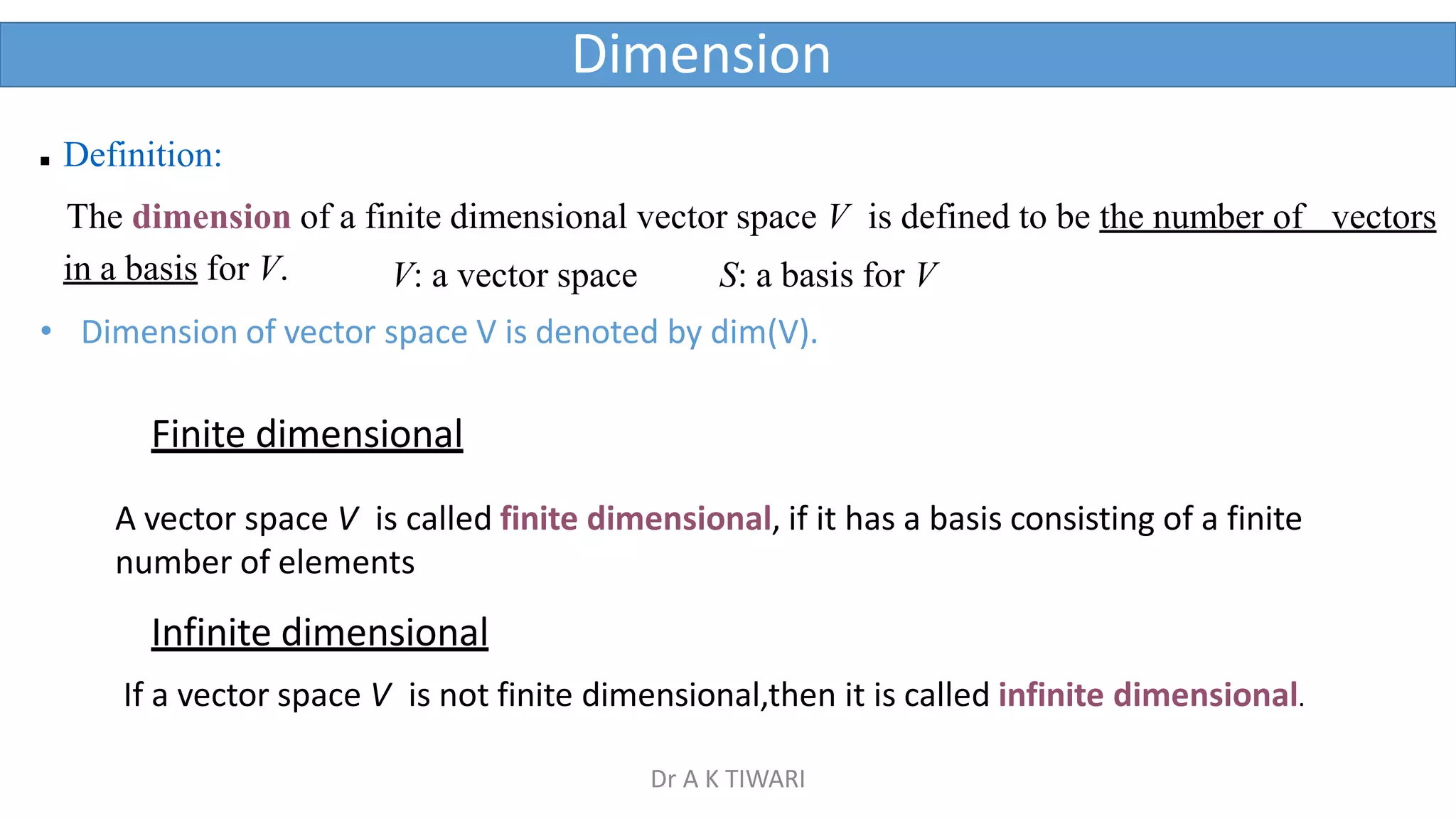

![

2 12 0

3 21

1

2 B B

B

[v]

1

[v] P[v]

(b)

2

1 2 ⁝ 3 4

0 1 ⁝ 2 3

1 0 ⁝ 1 2

G.J.E.

B'

2 ⁝ 2 2

B I P

-1

3

2 (the transition matrix from B to B')

2

P1

1

Check: 2

1

3 0 I

1 2

3 2 1 2 1 0

PP 2

1

0

2

Check:

[v]

1

v (1)(3,2) (0)(4,2) (3,2)

[v]

1

v (1)(1,2) (2)(2,2) (3,2)

B

B

(c)

Dr A K TIWARI](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vectorspace-230520021922-e87be485/75/Vector-Space-pptx-48-2048.jpg)