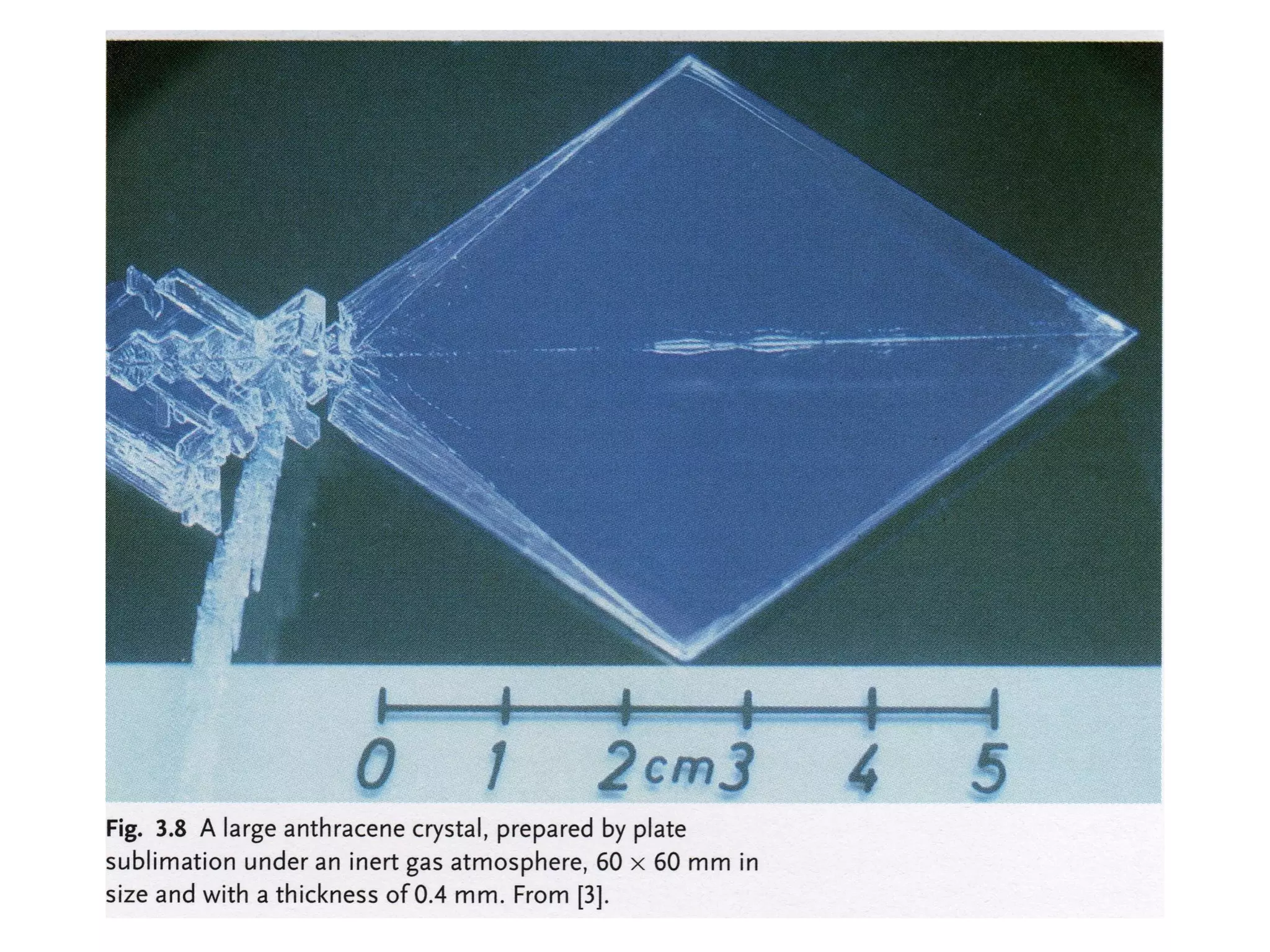

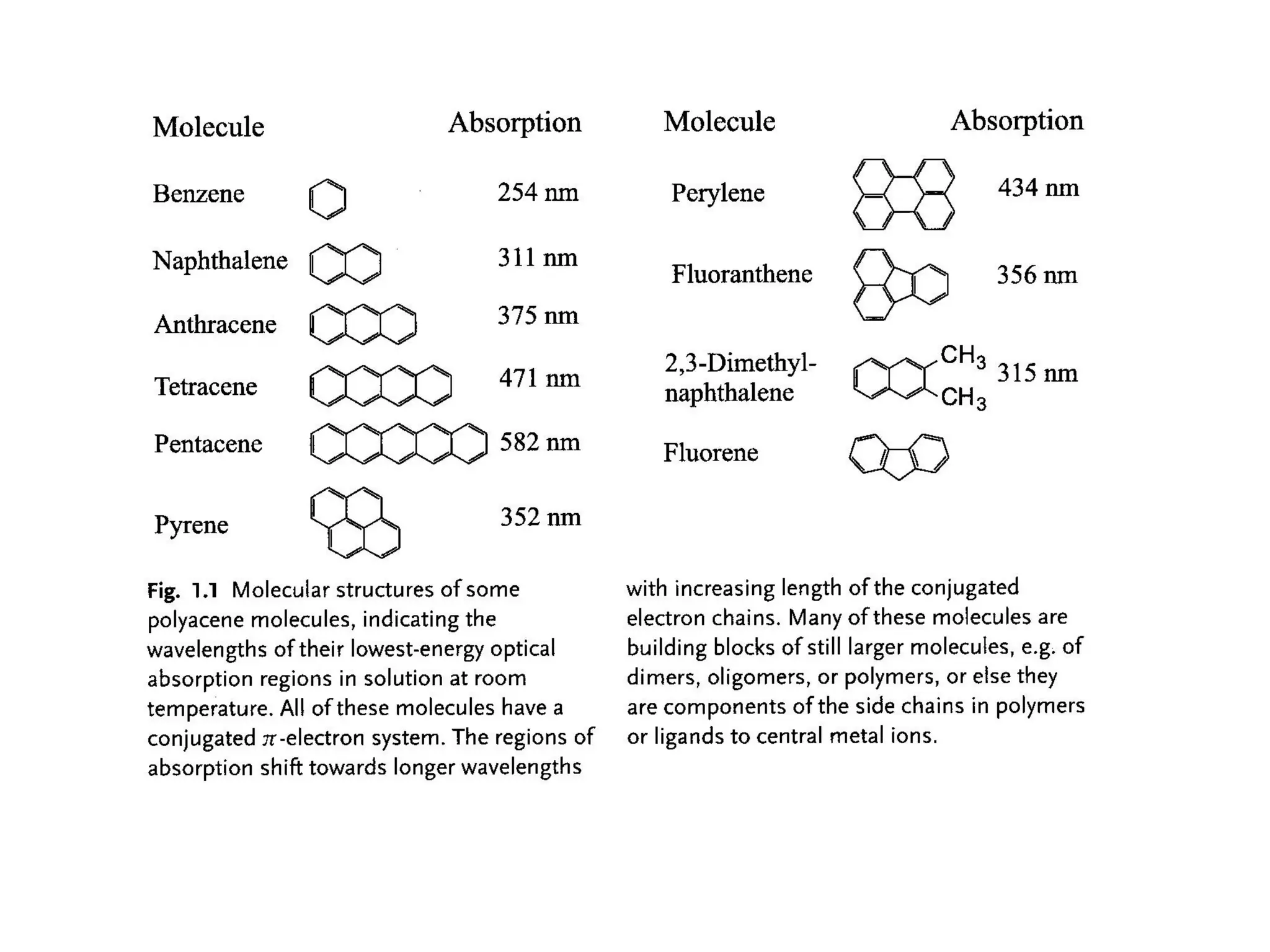

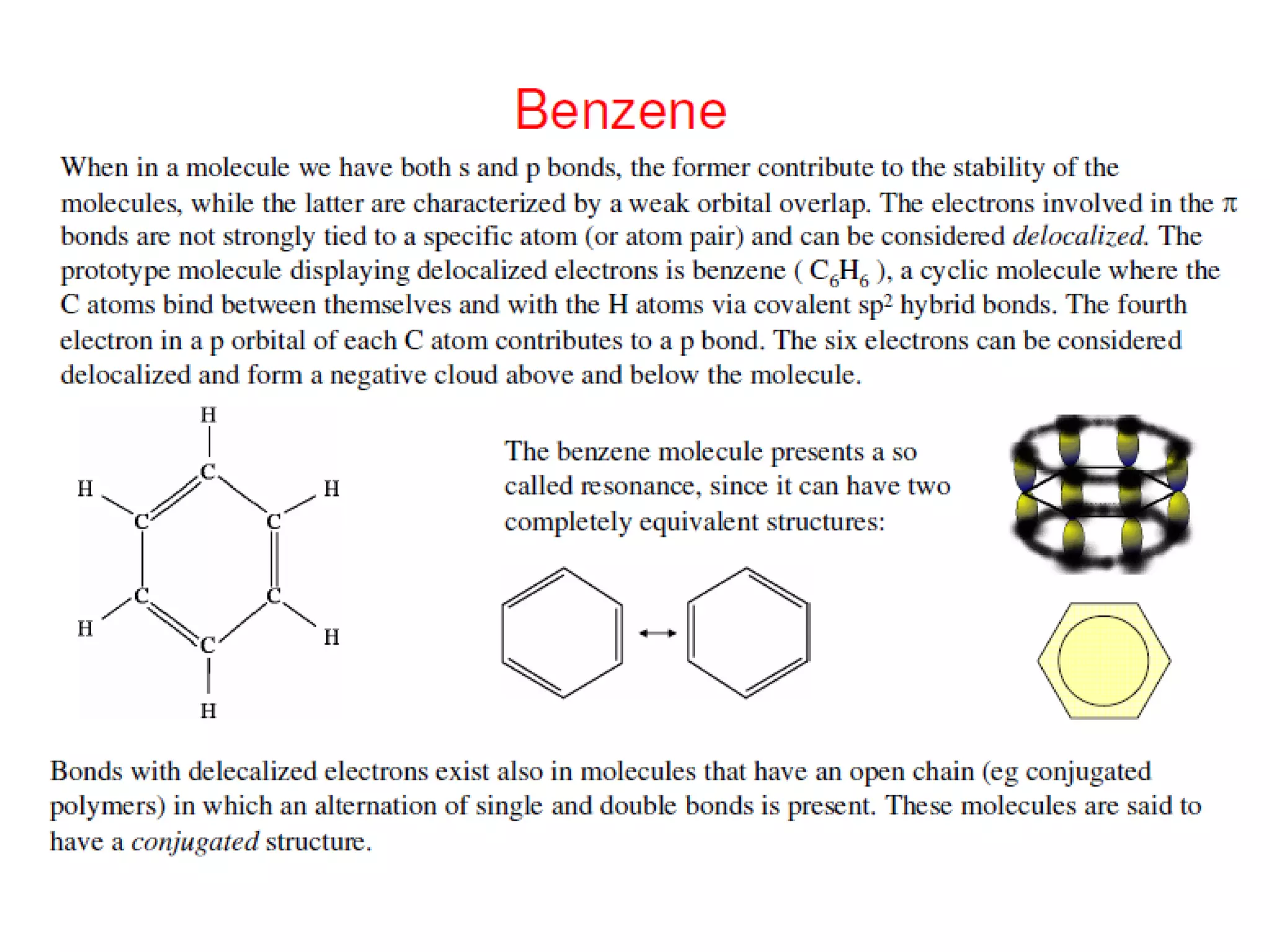

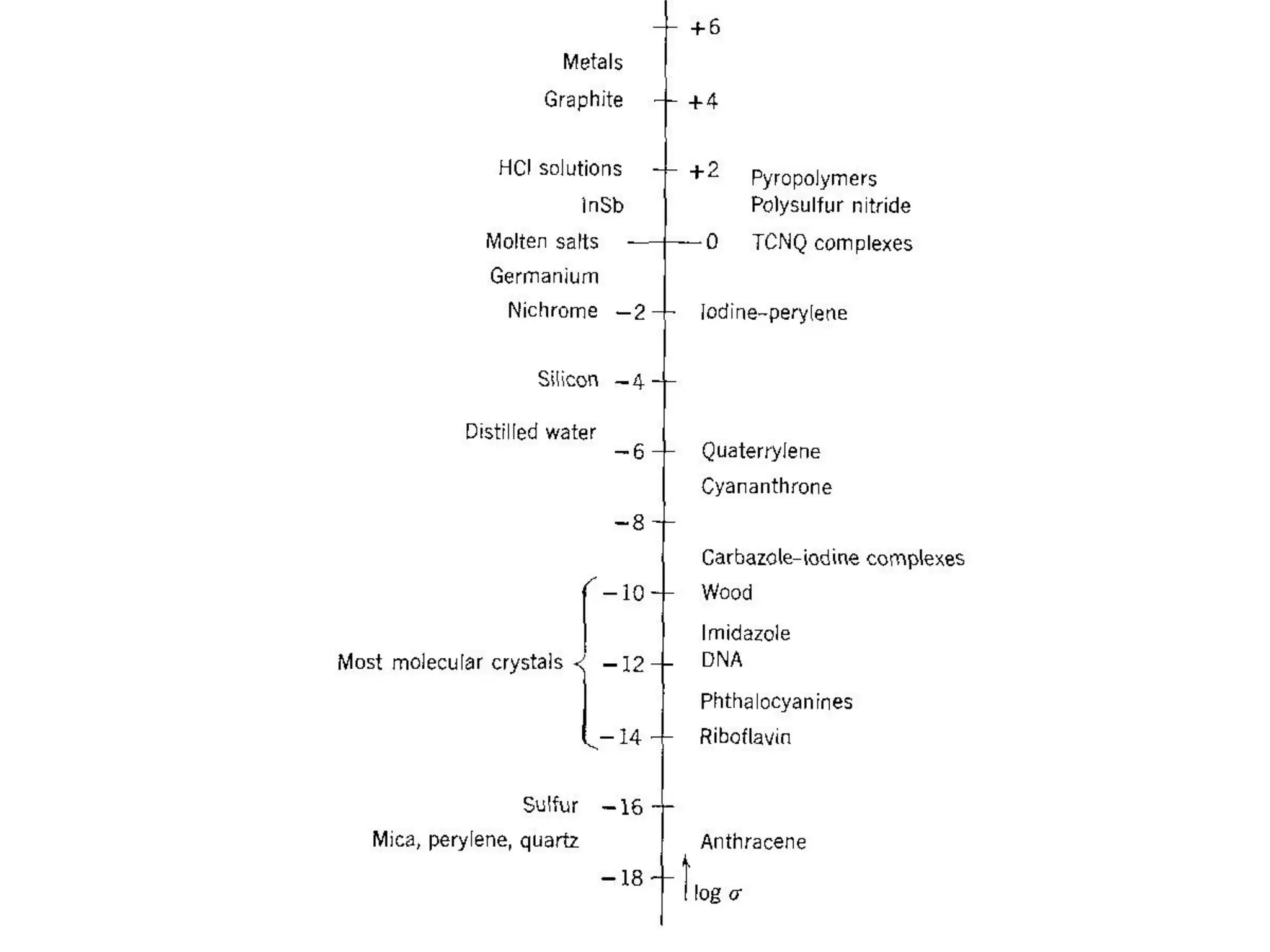

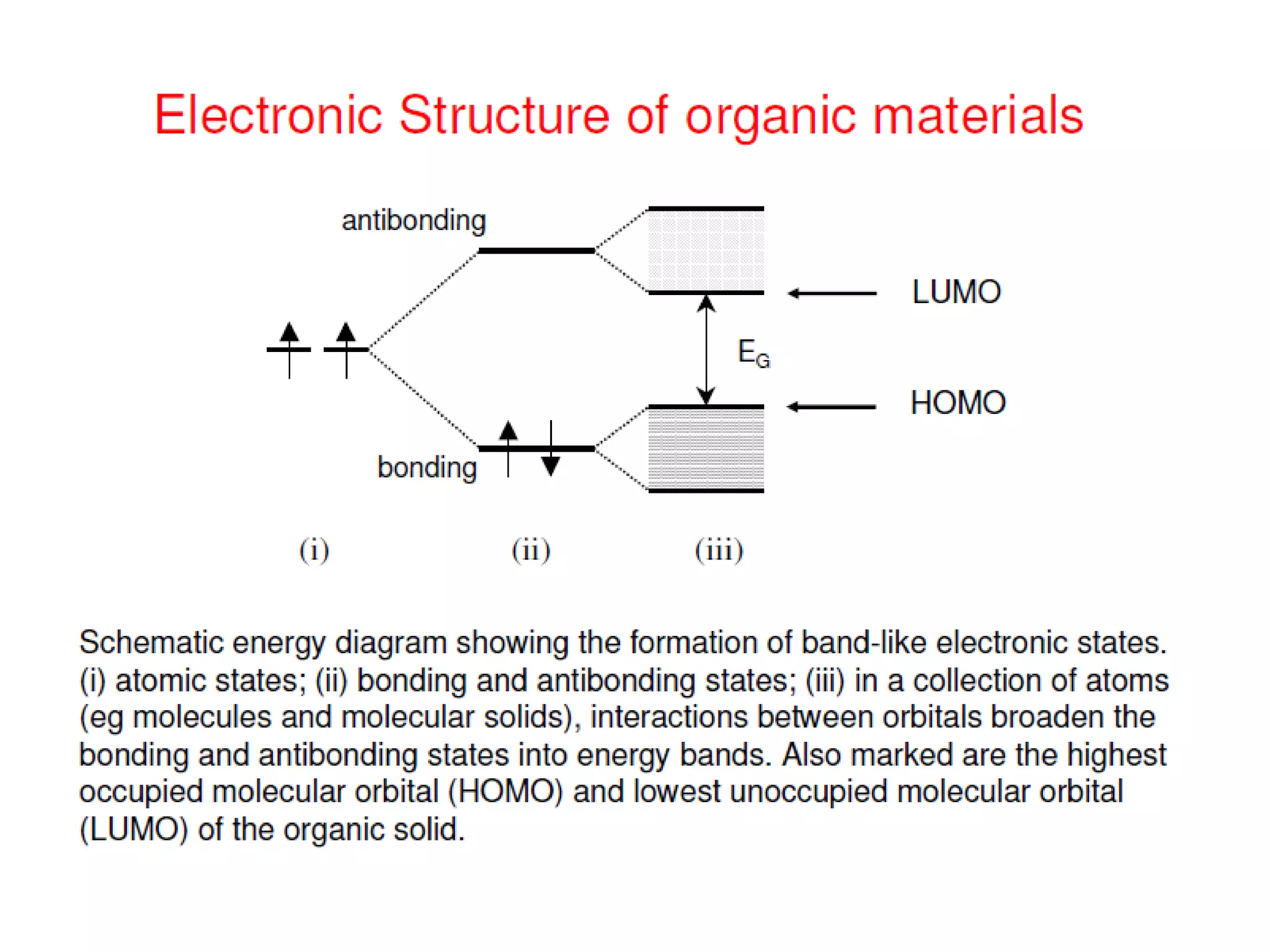

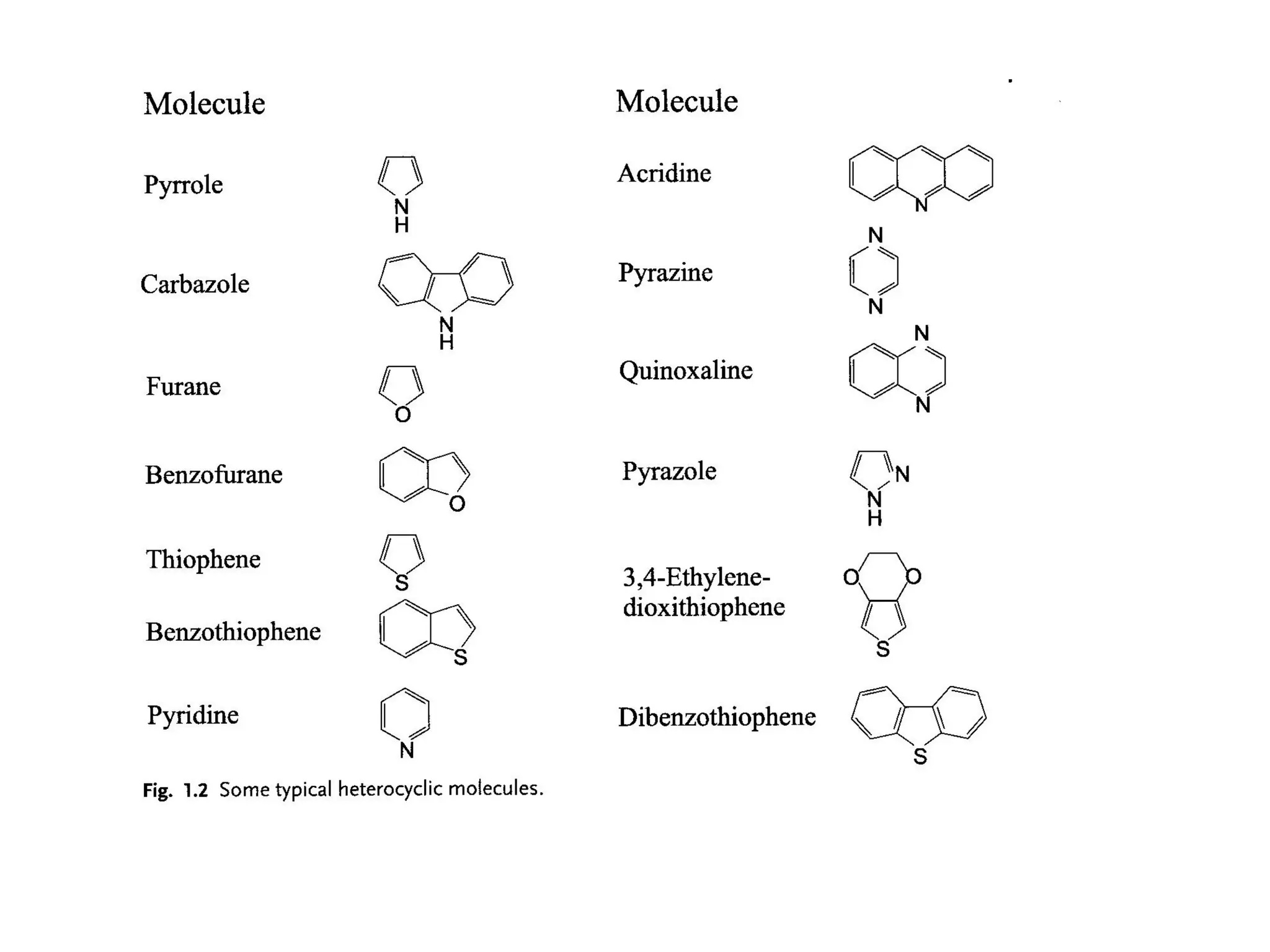

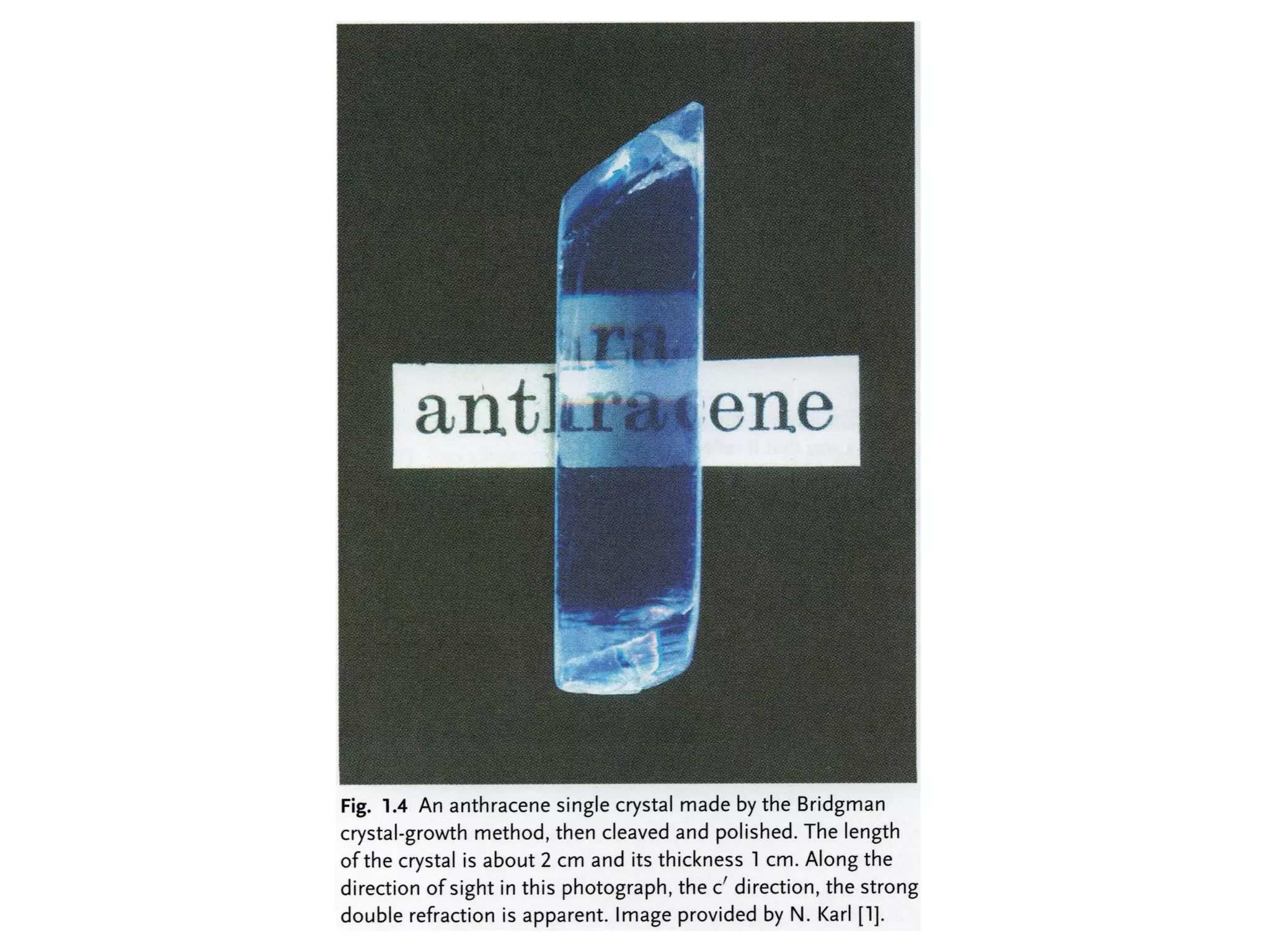

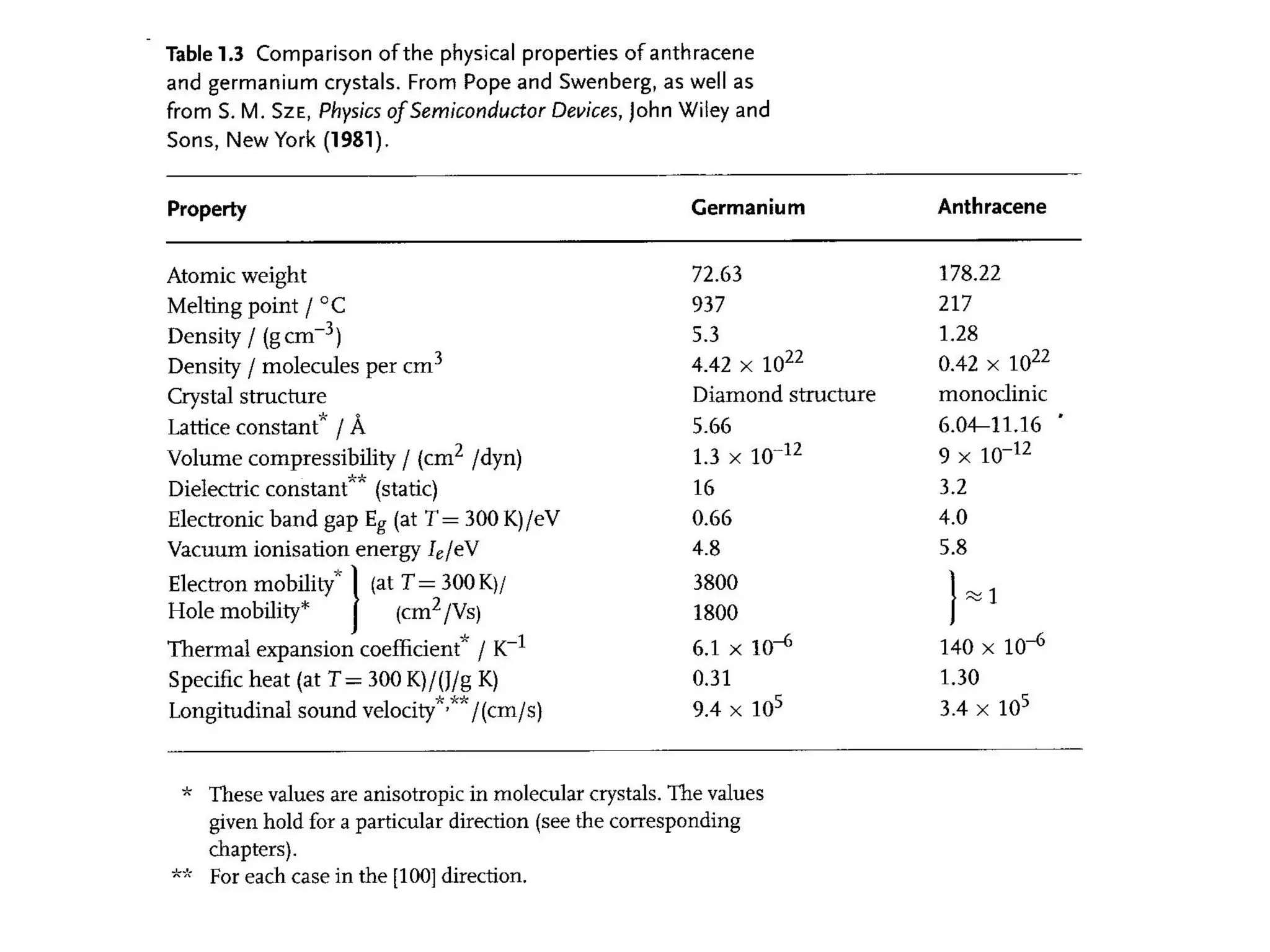

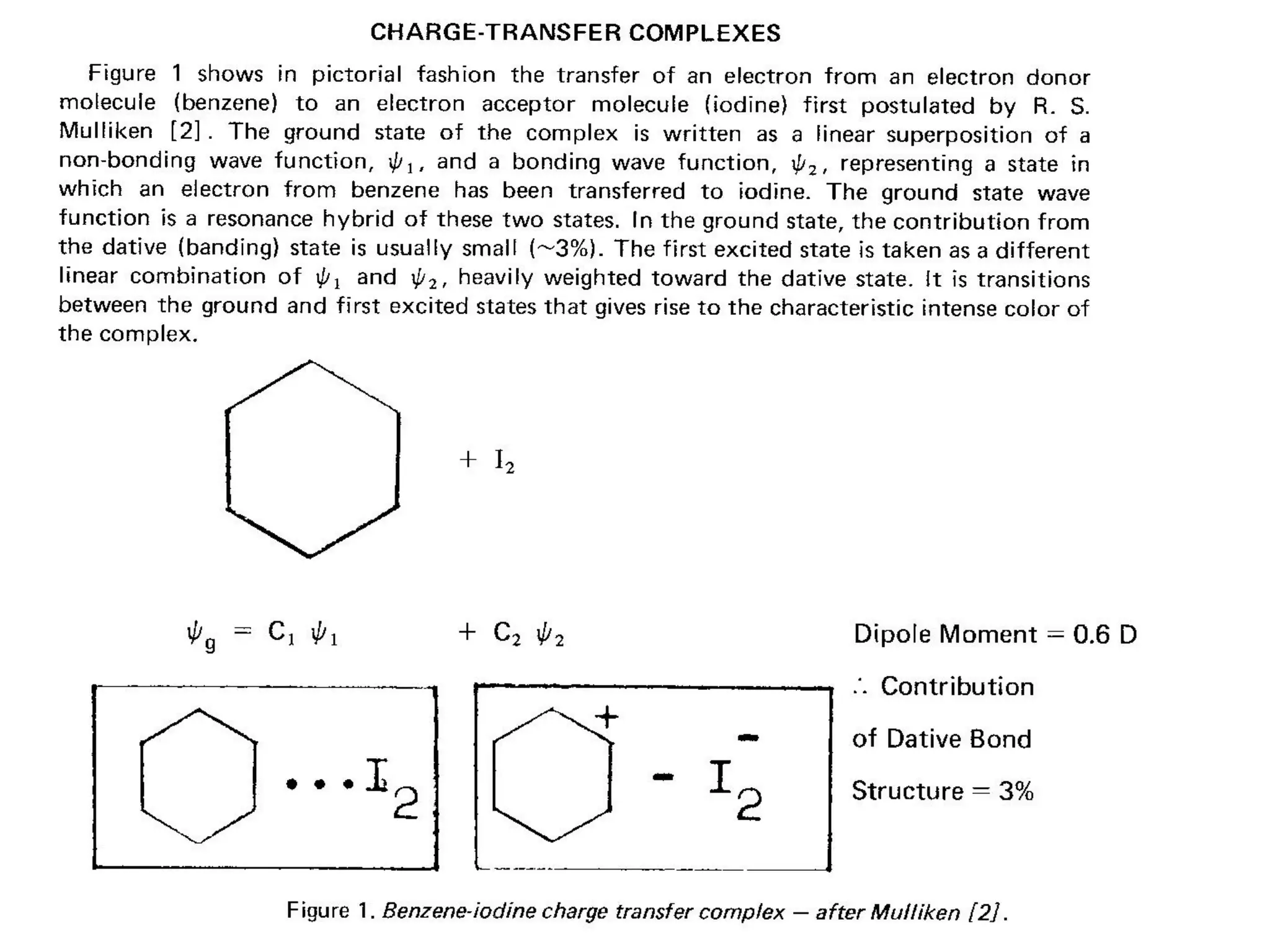

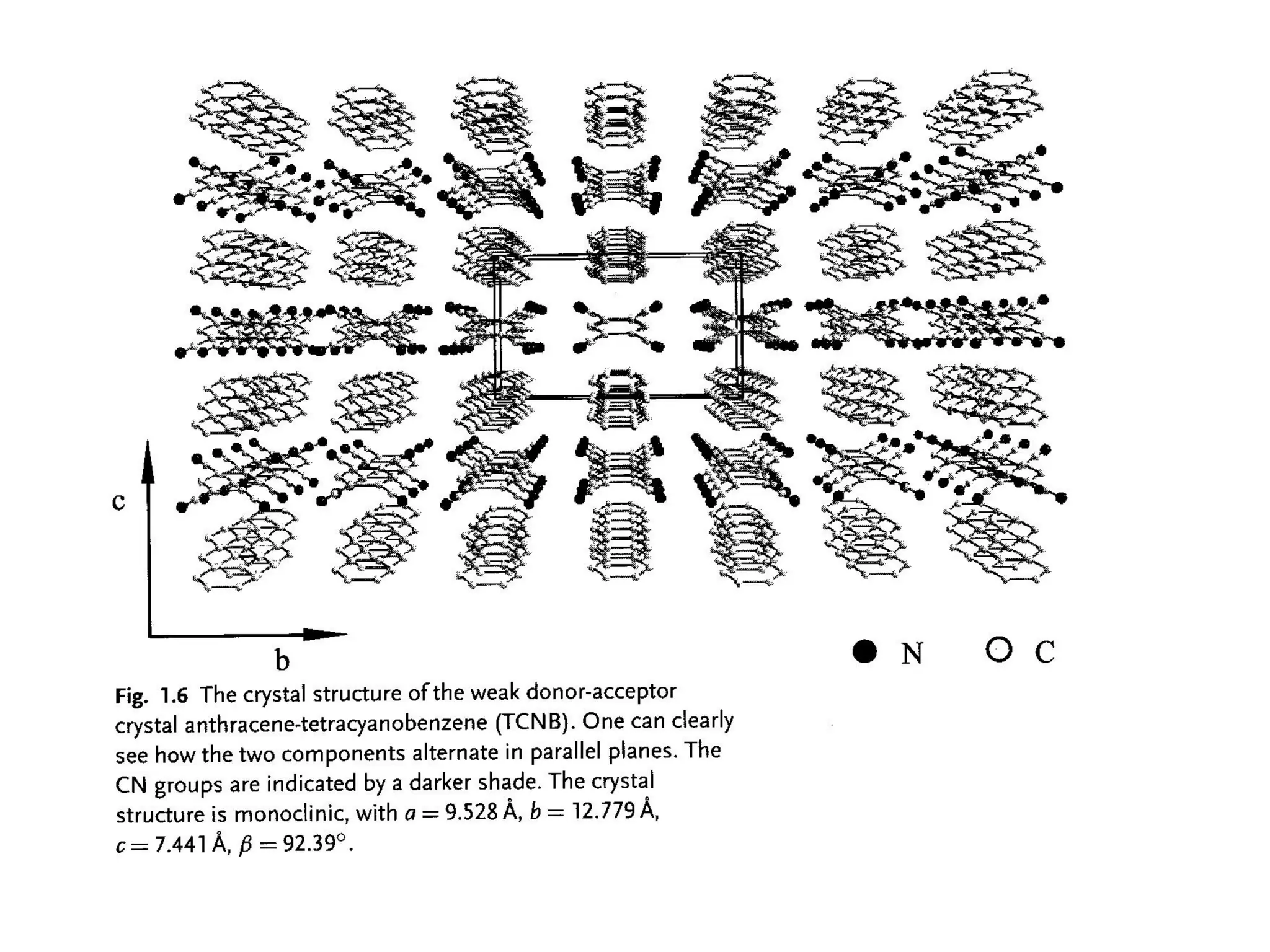

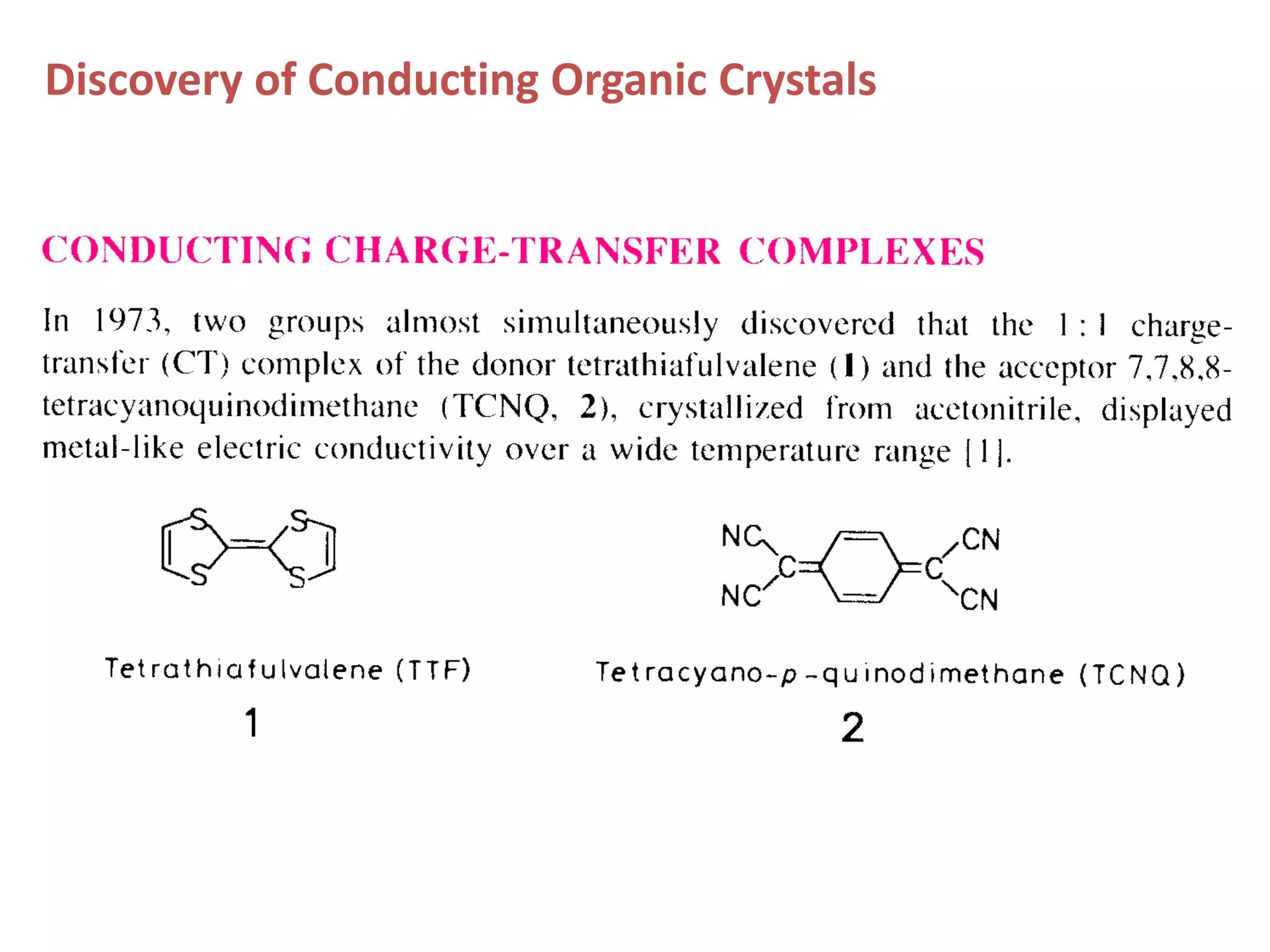

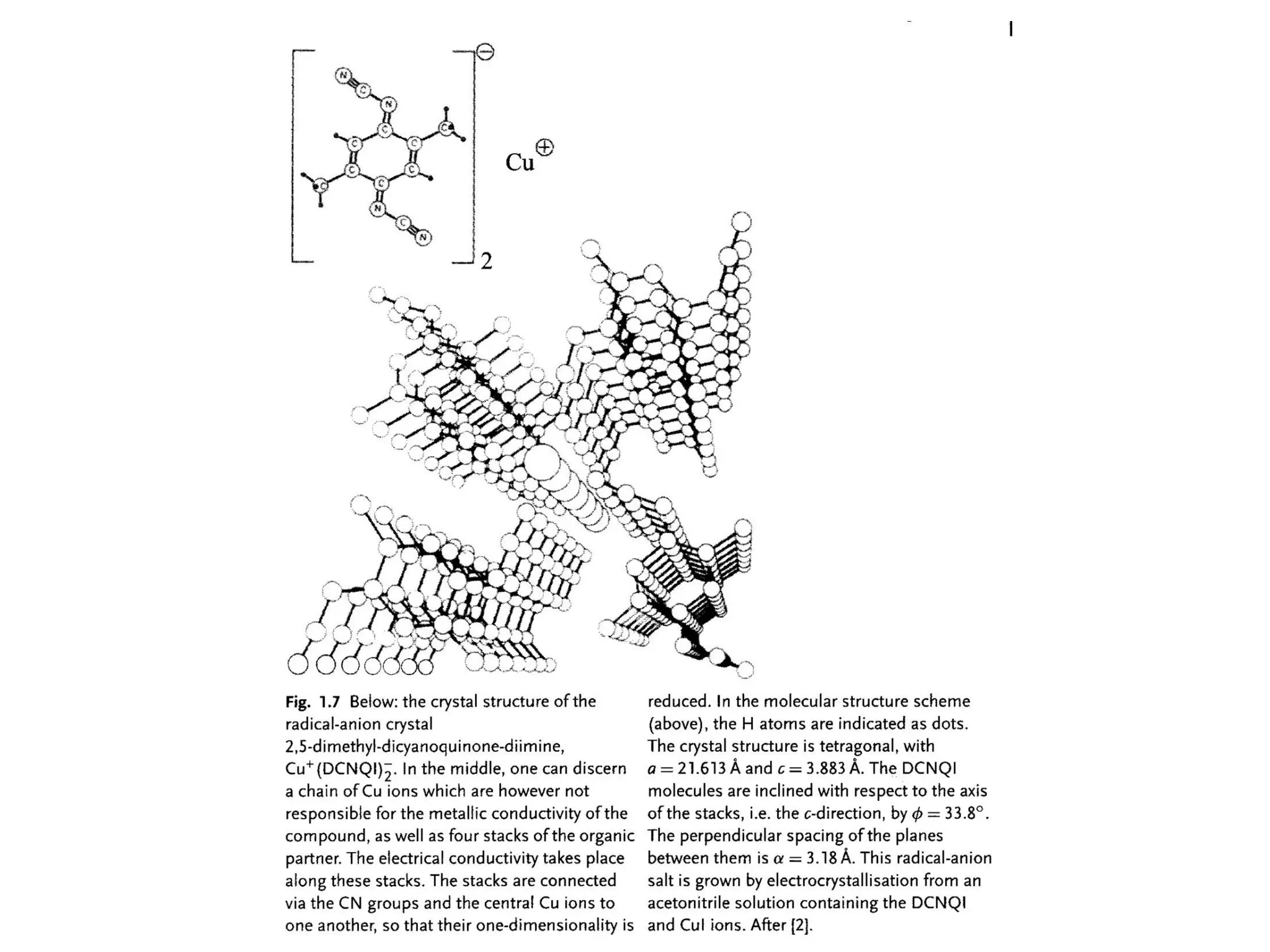

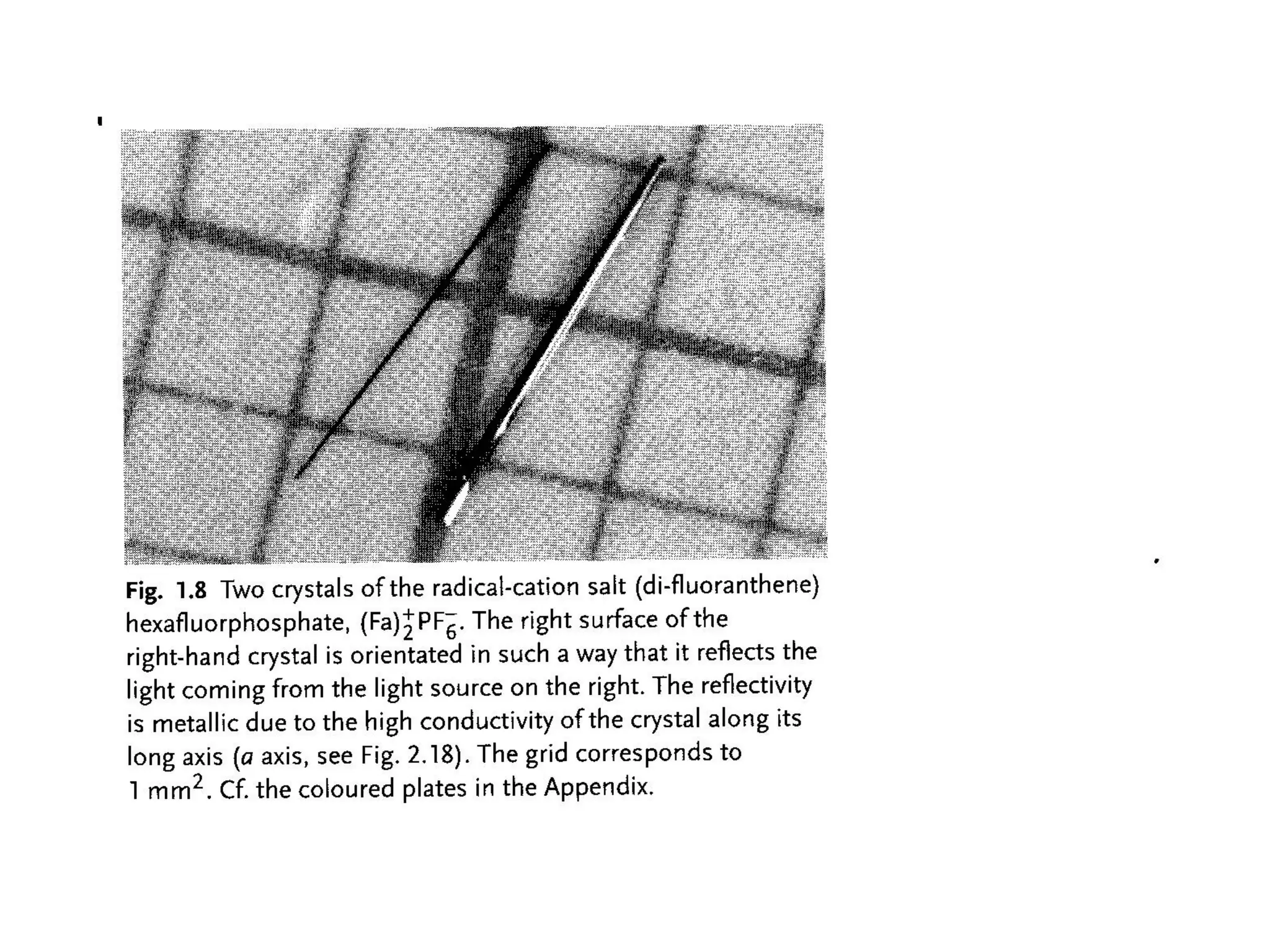

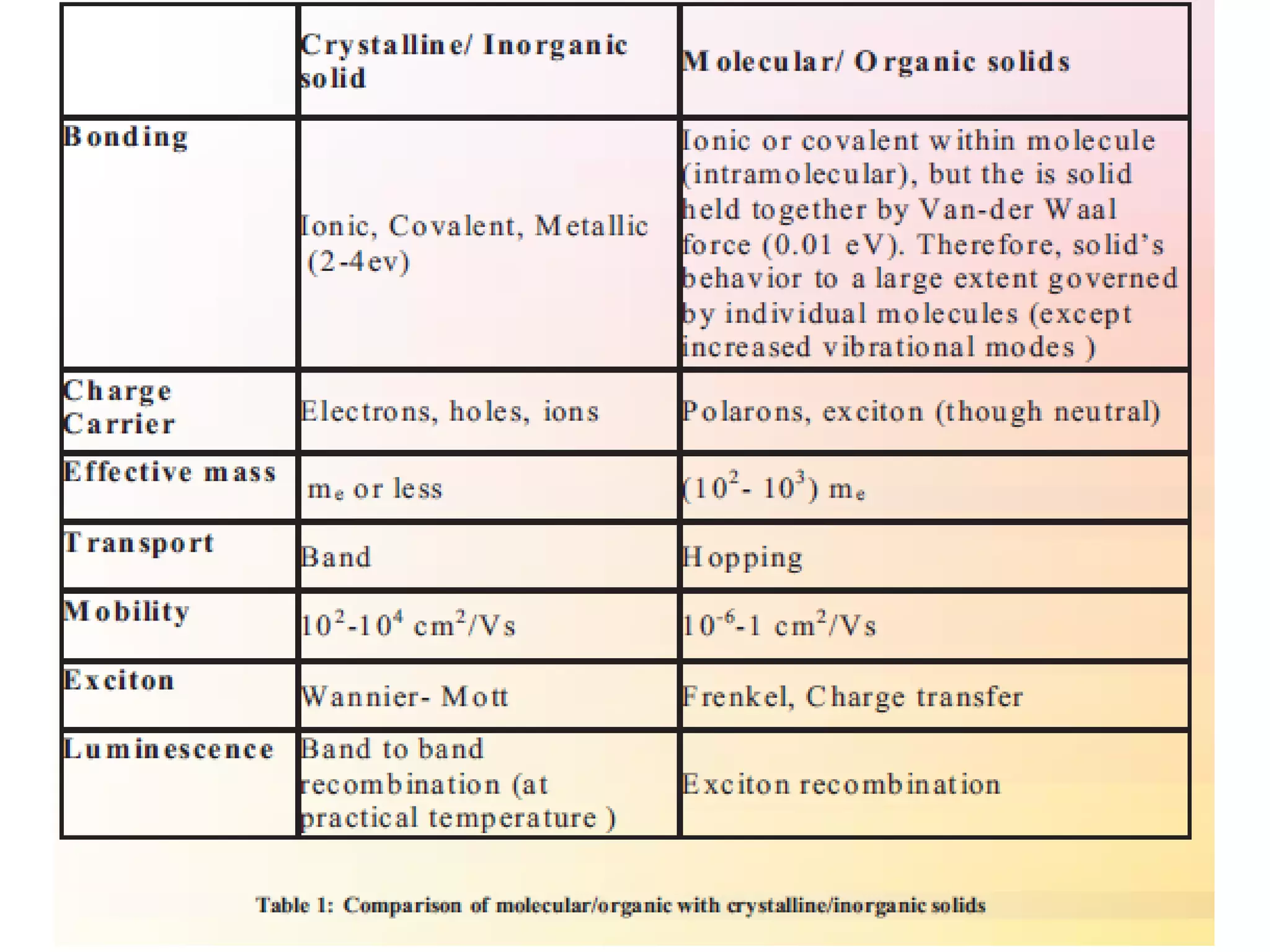

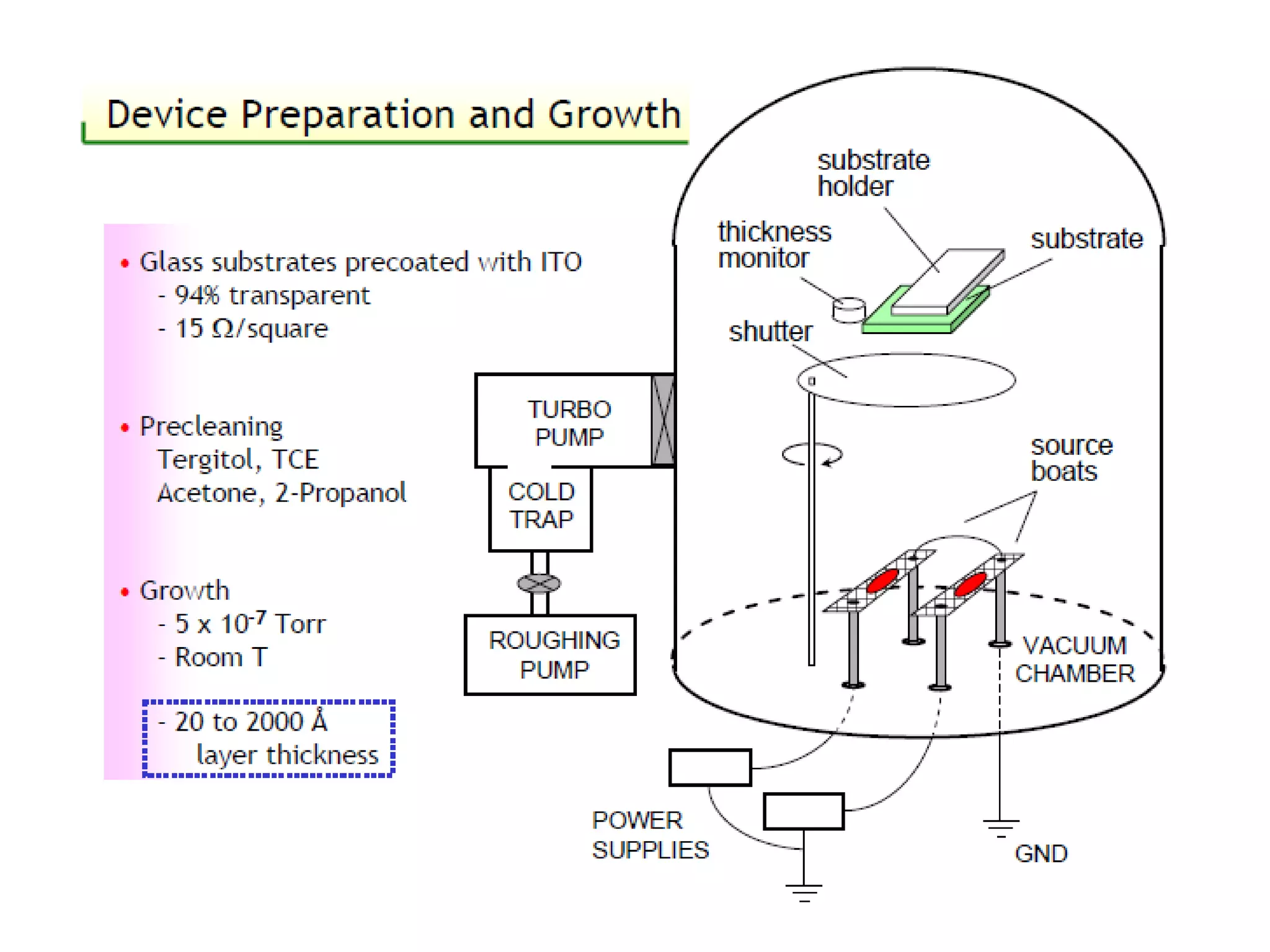

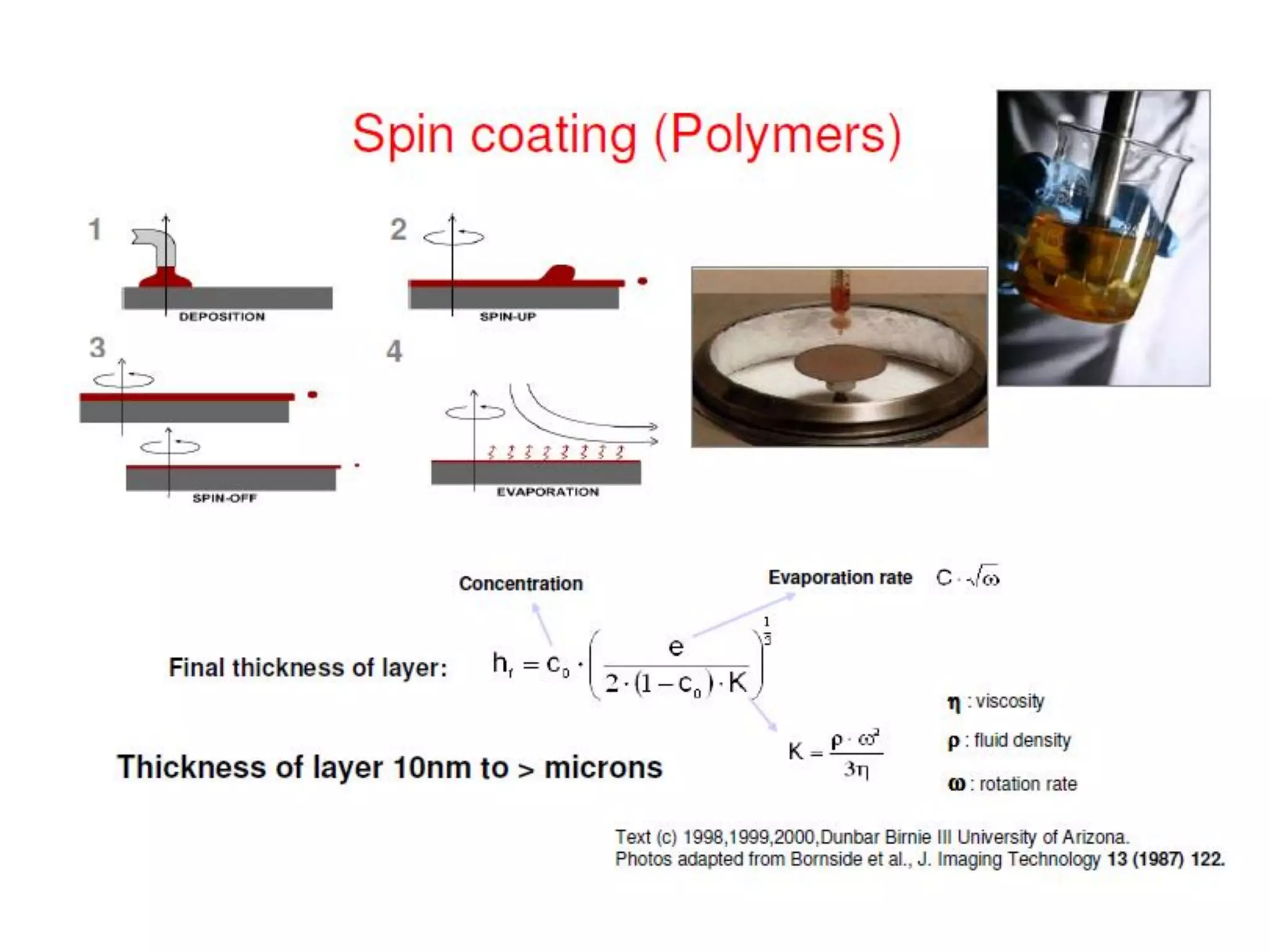

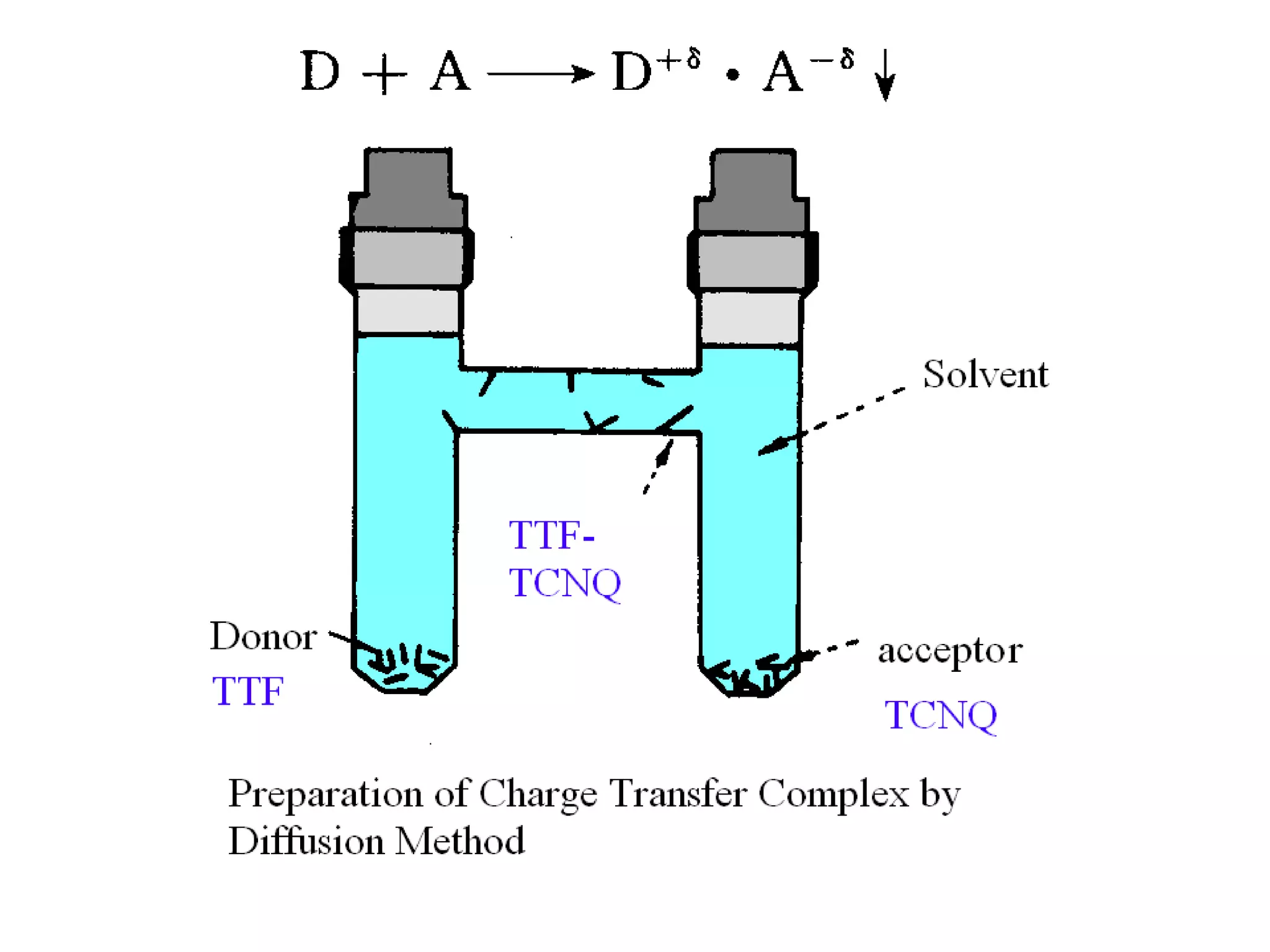

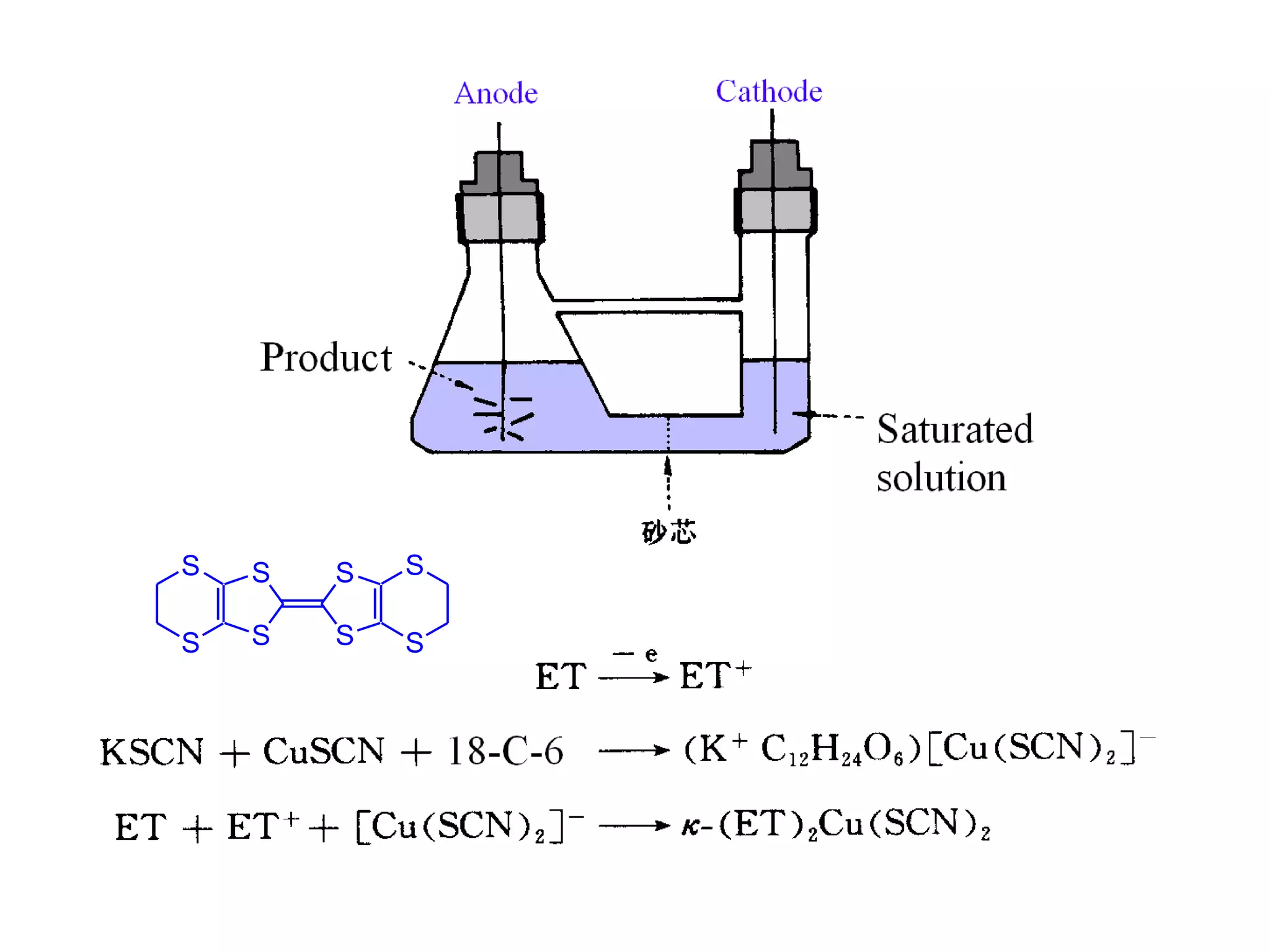

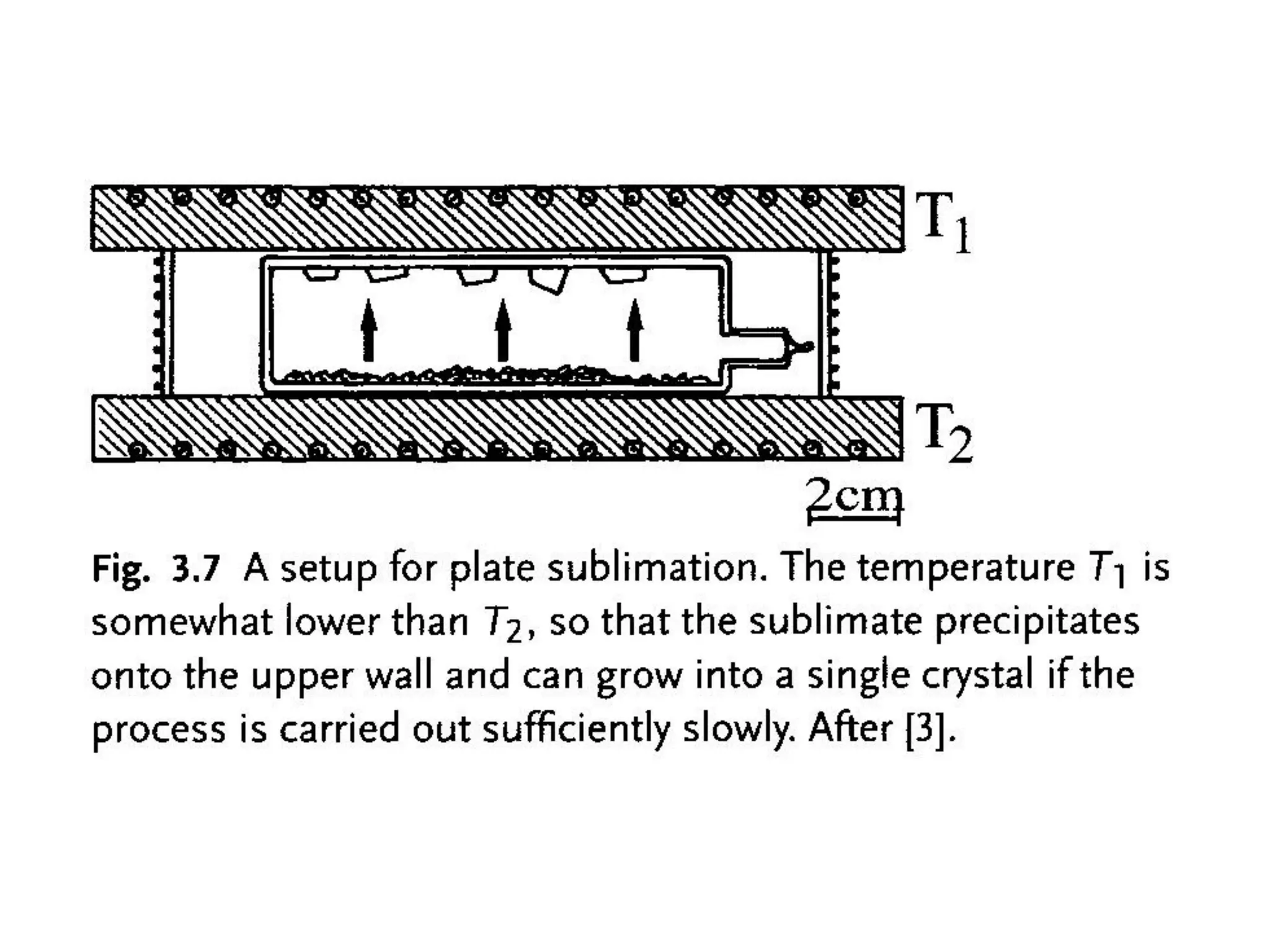

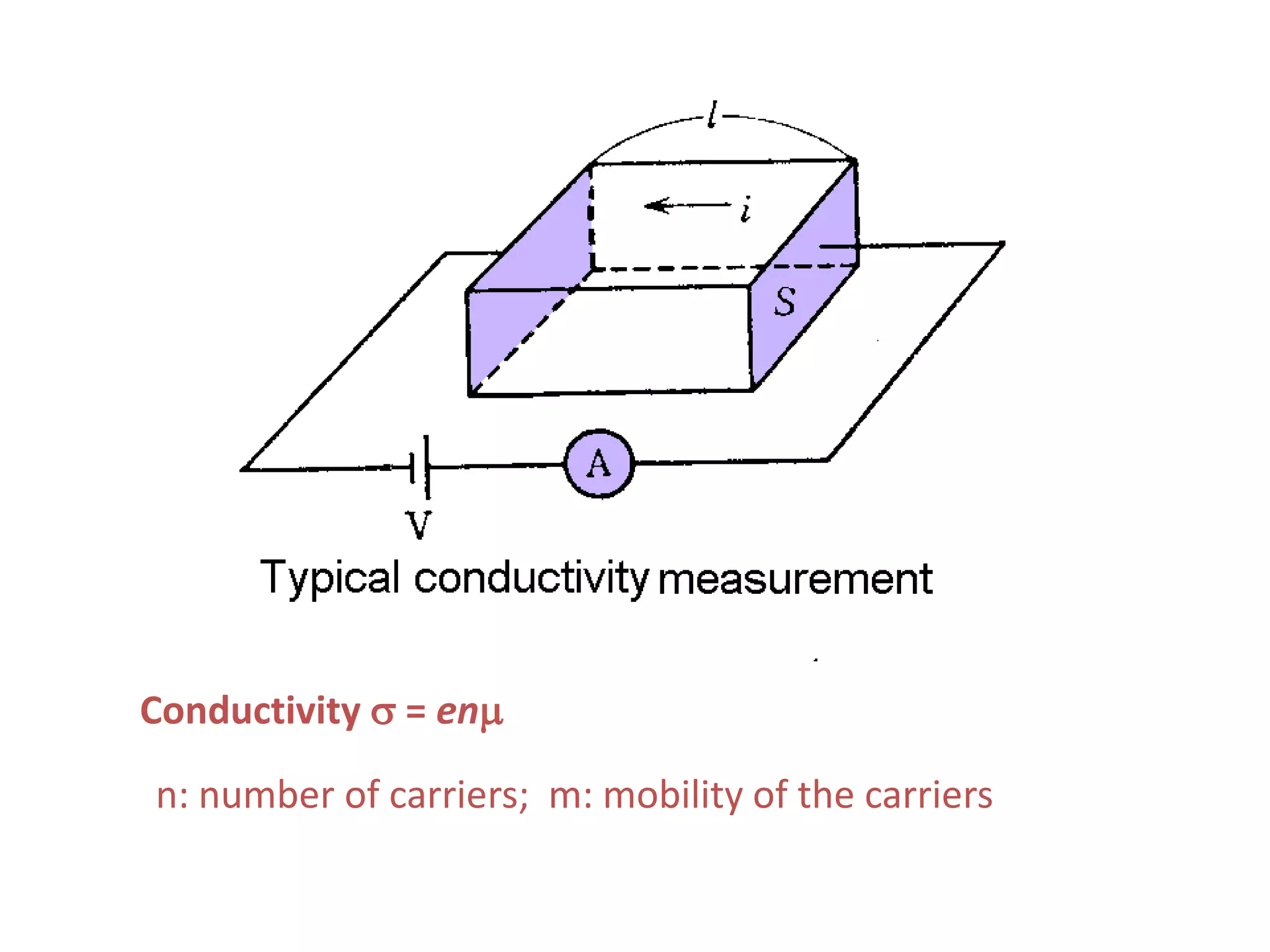

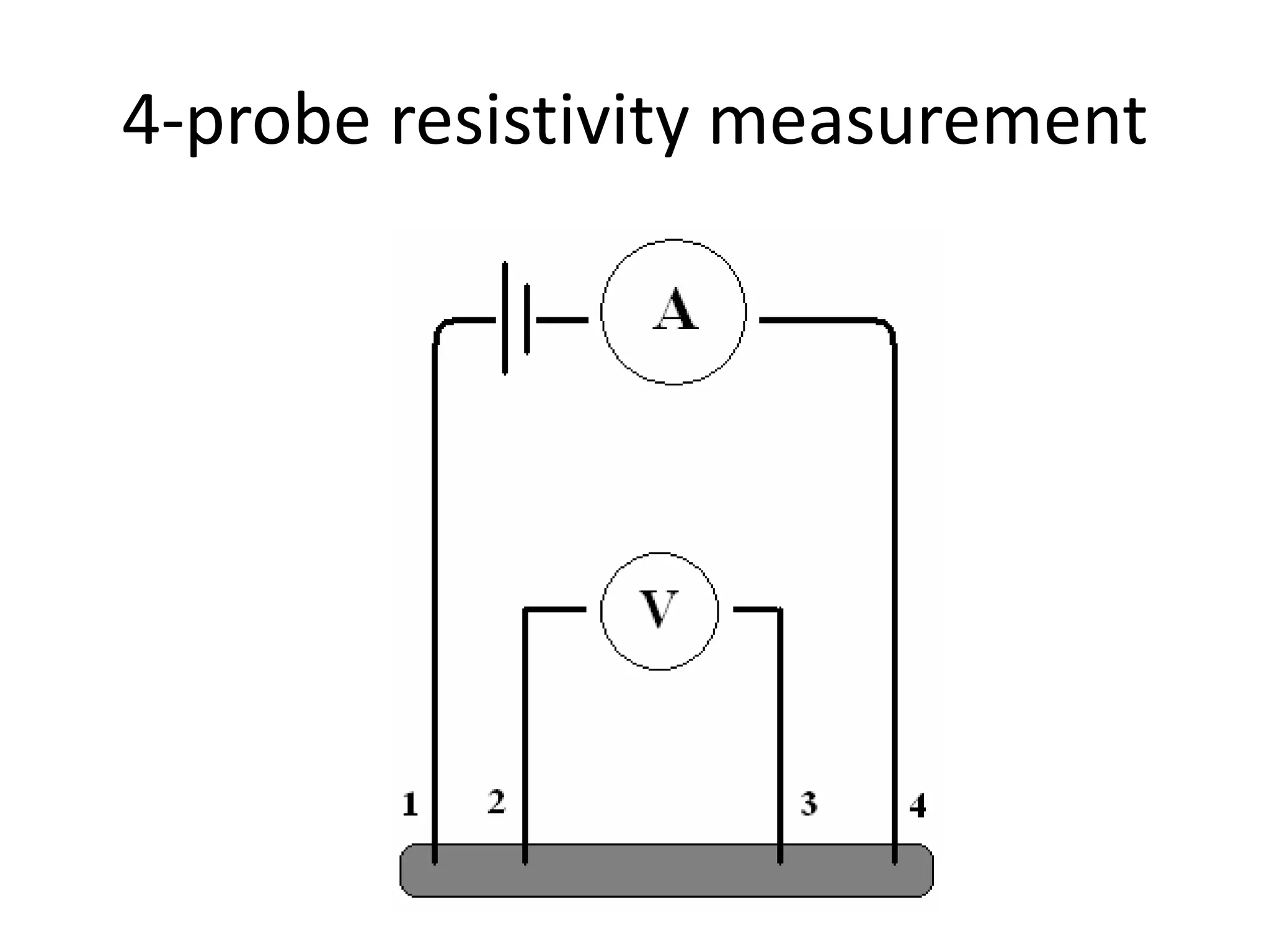

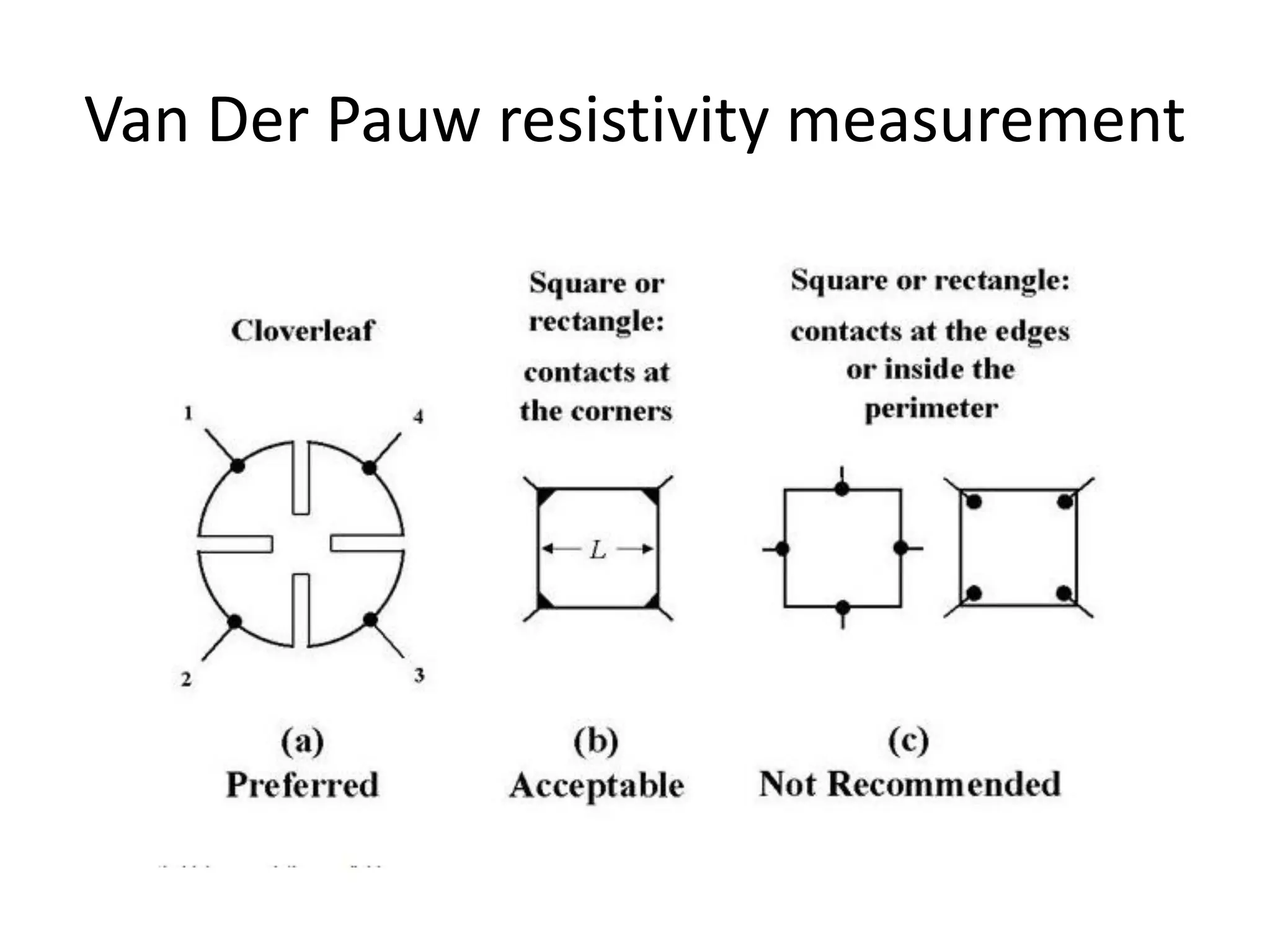

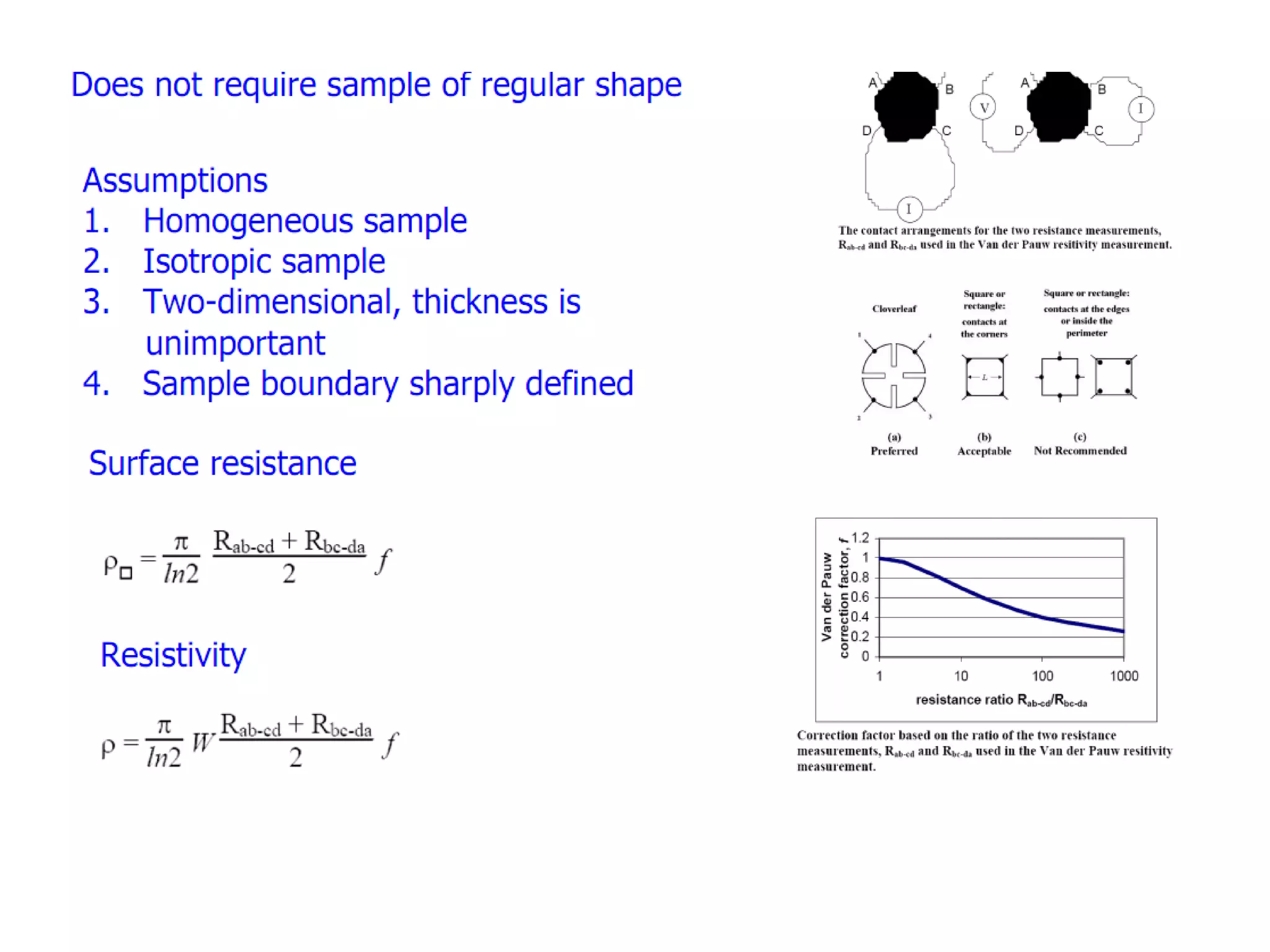

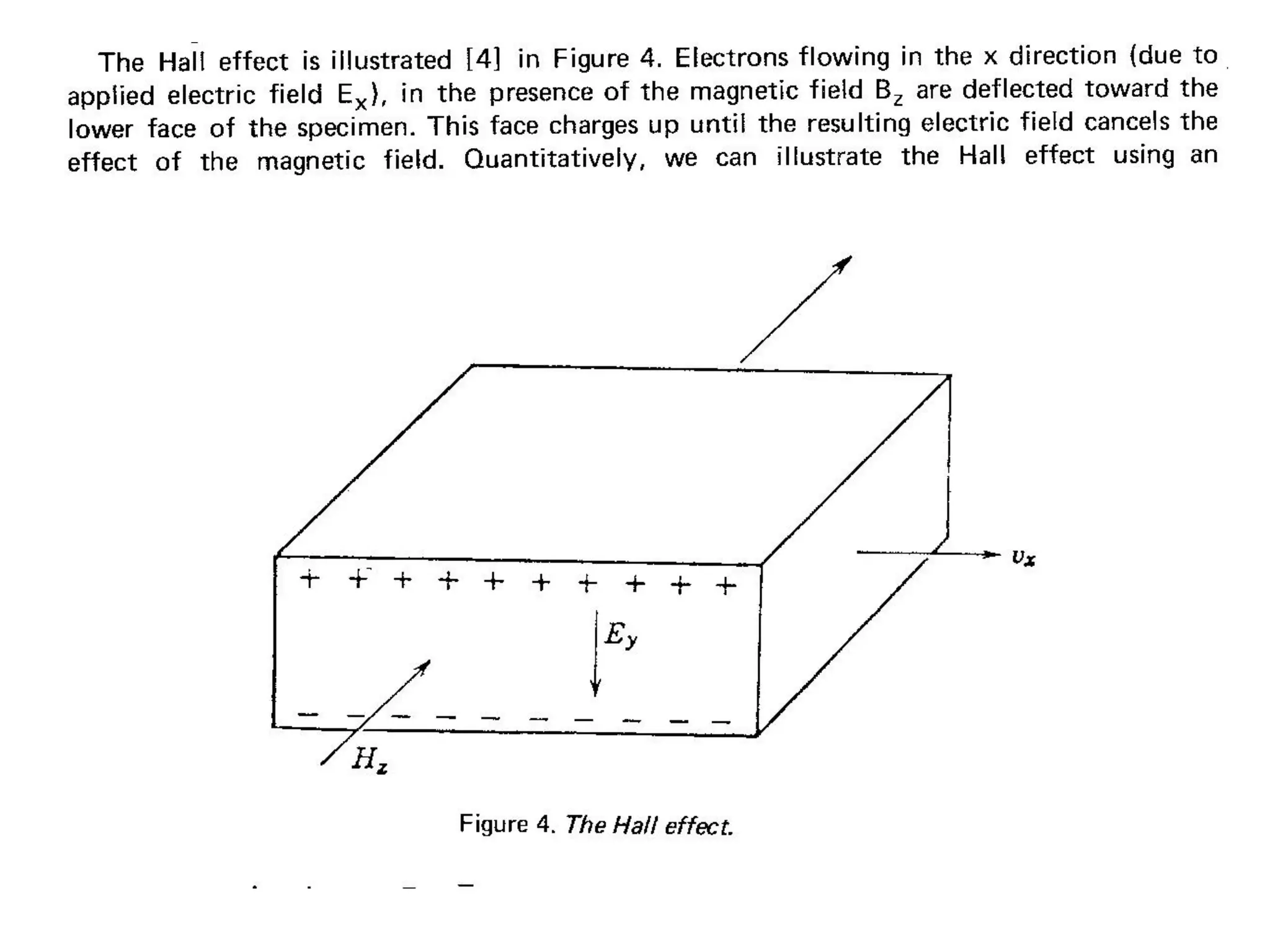

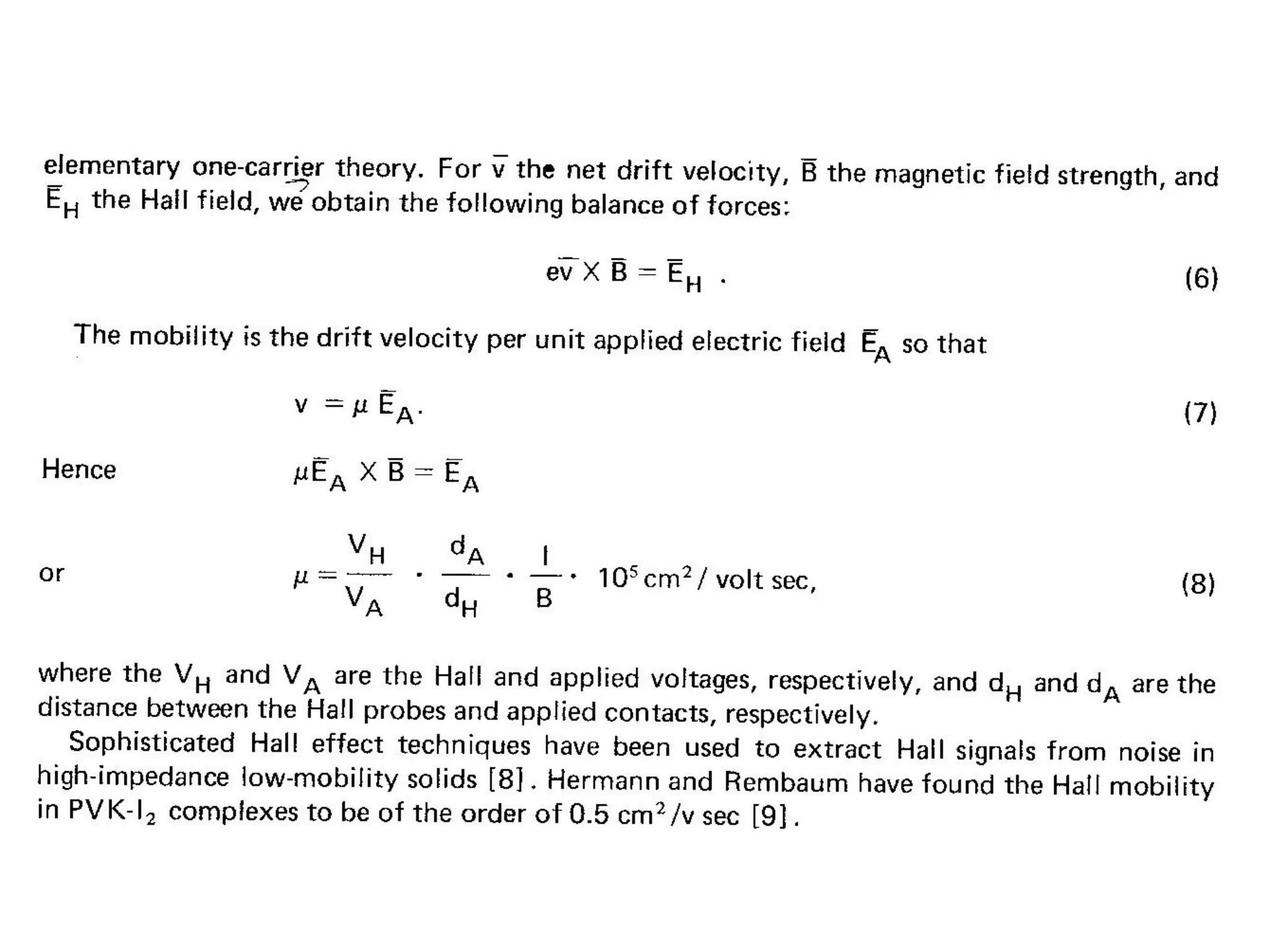

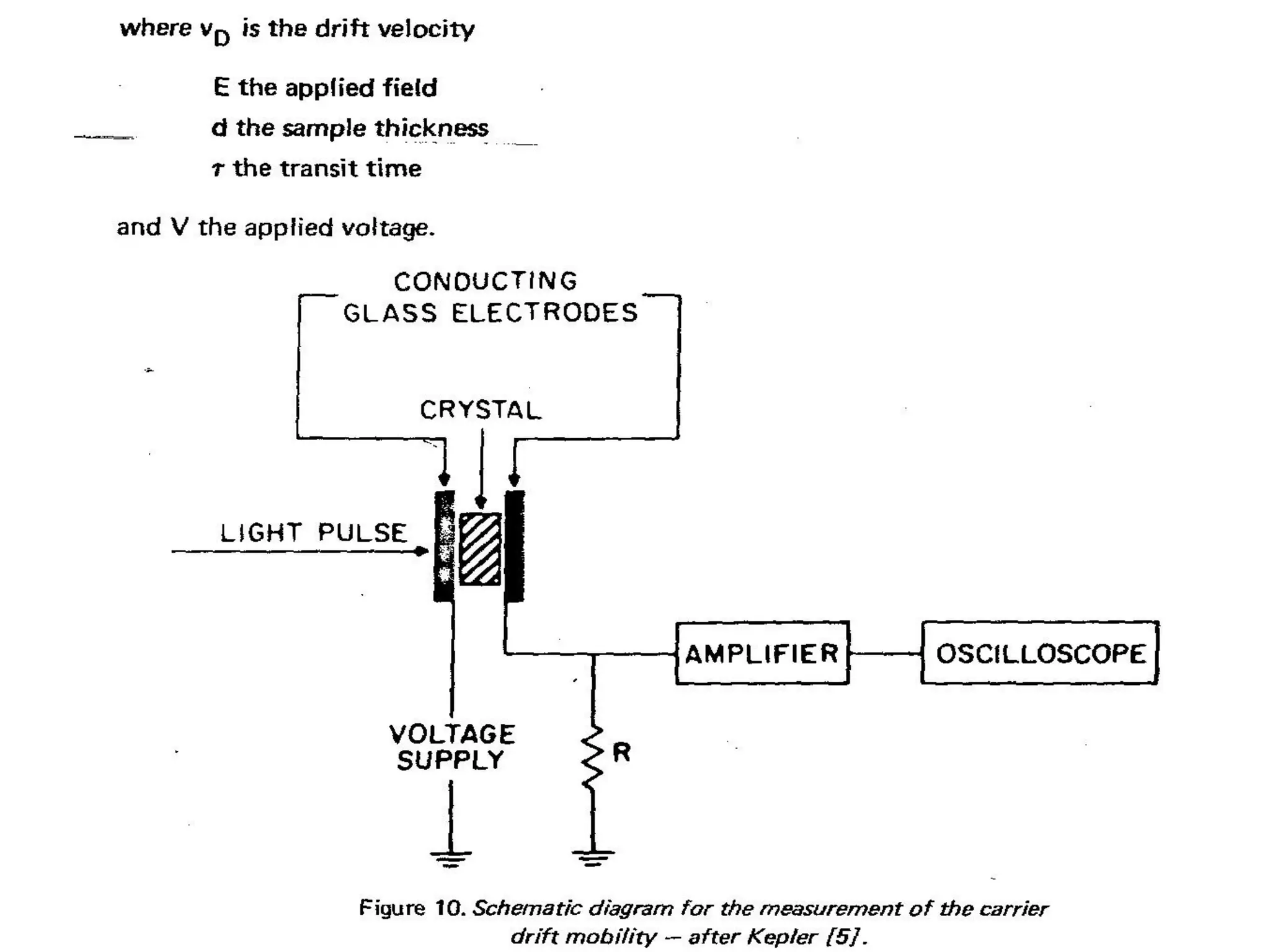

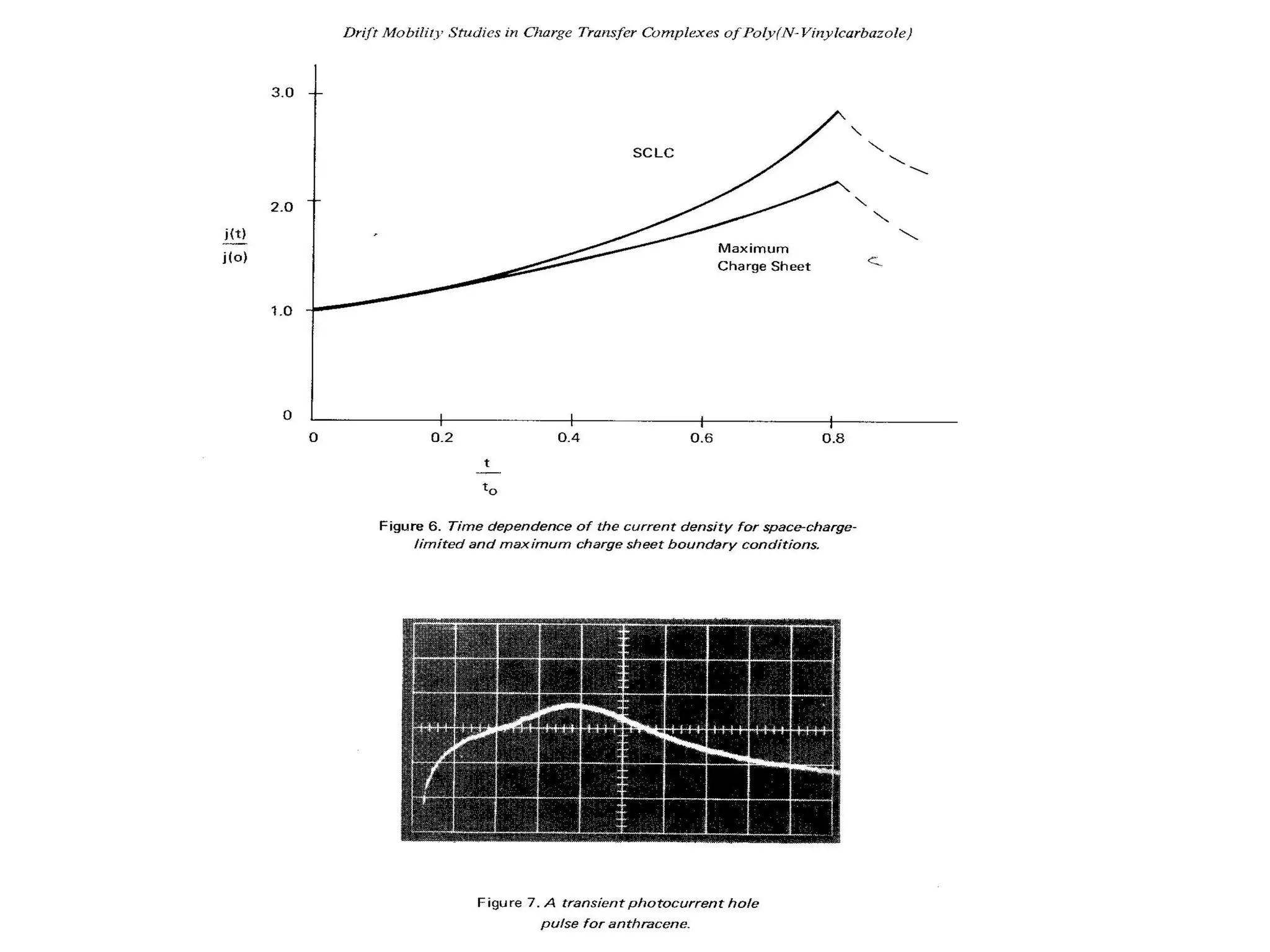

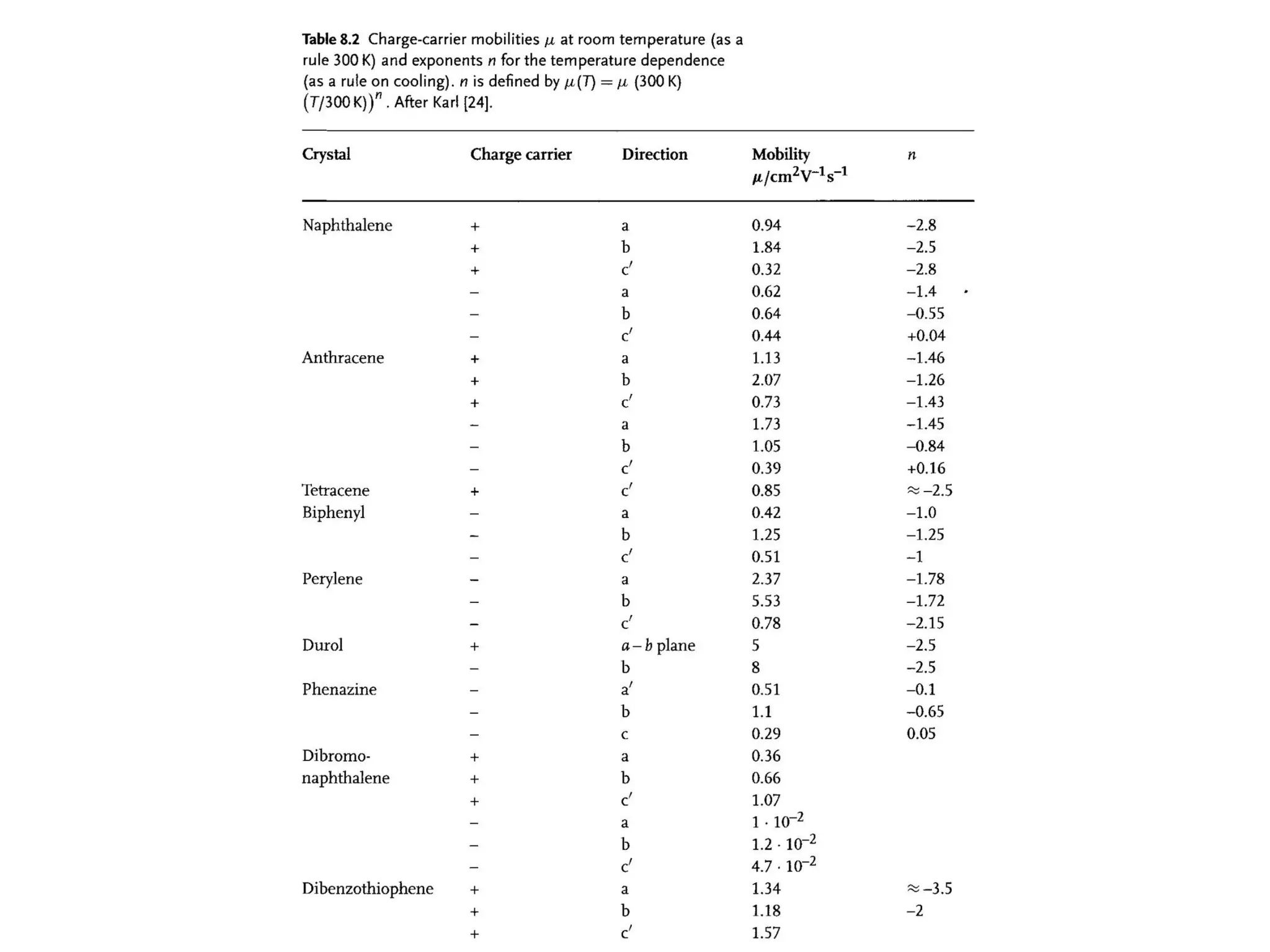

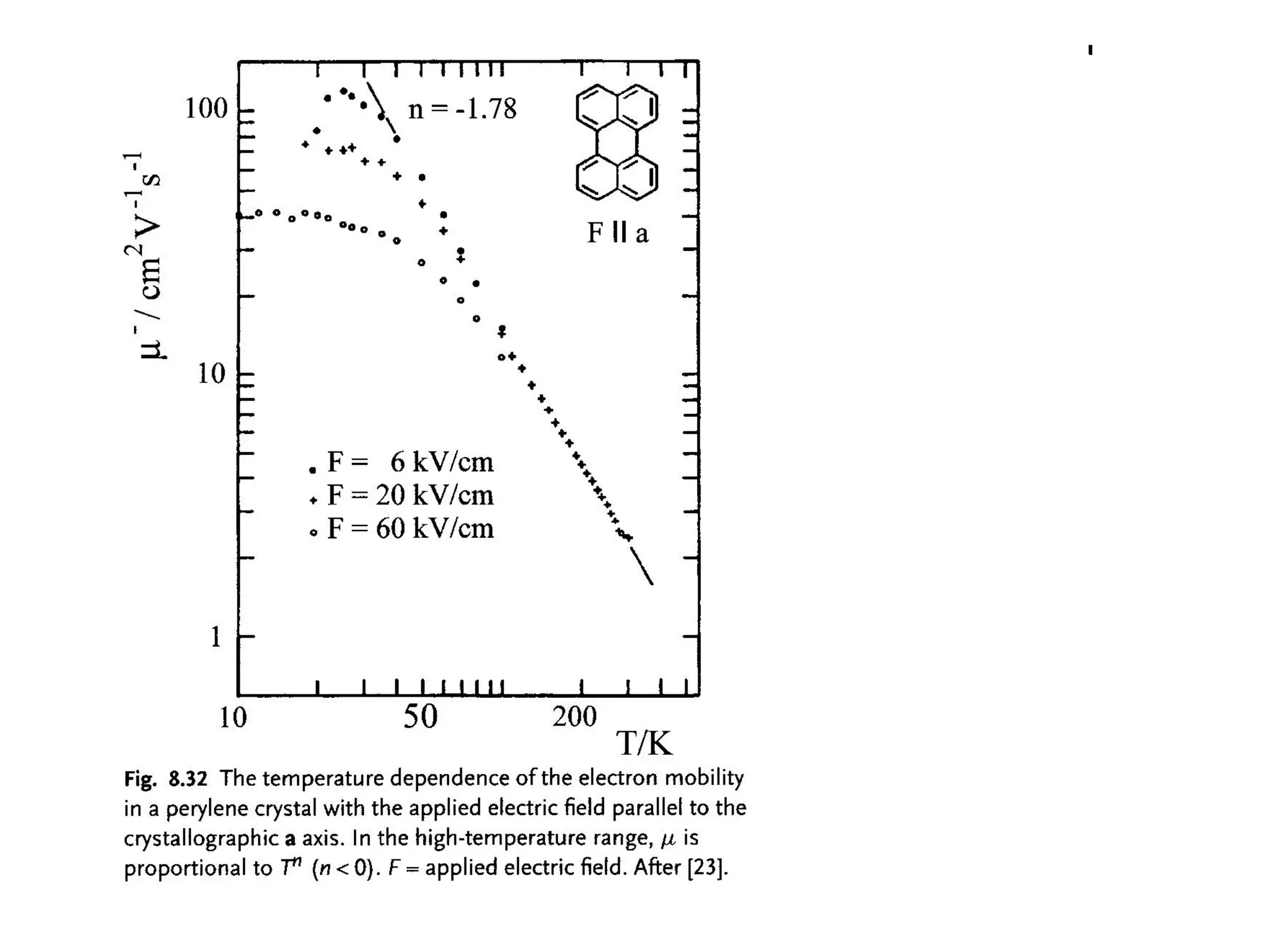

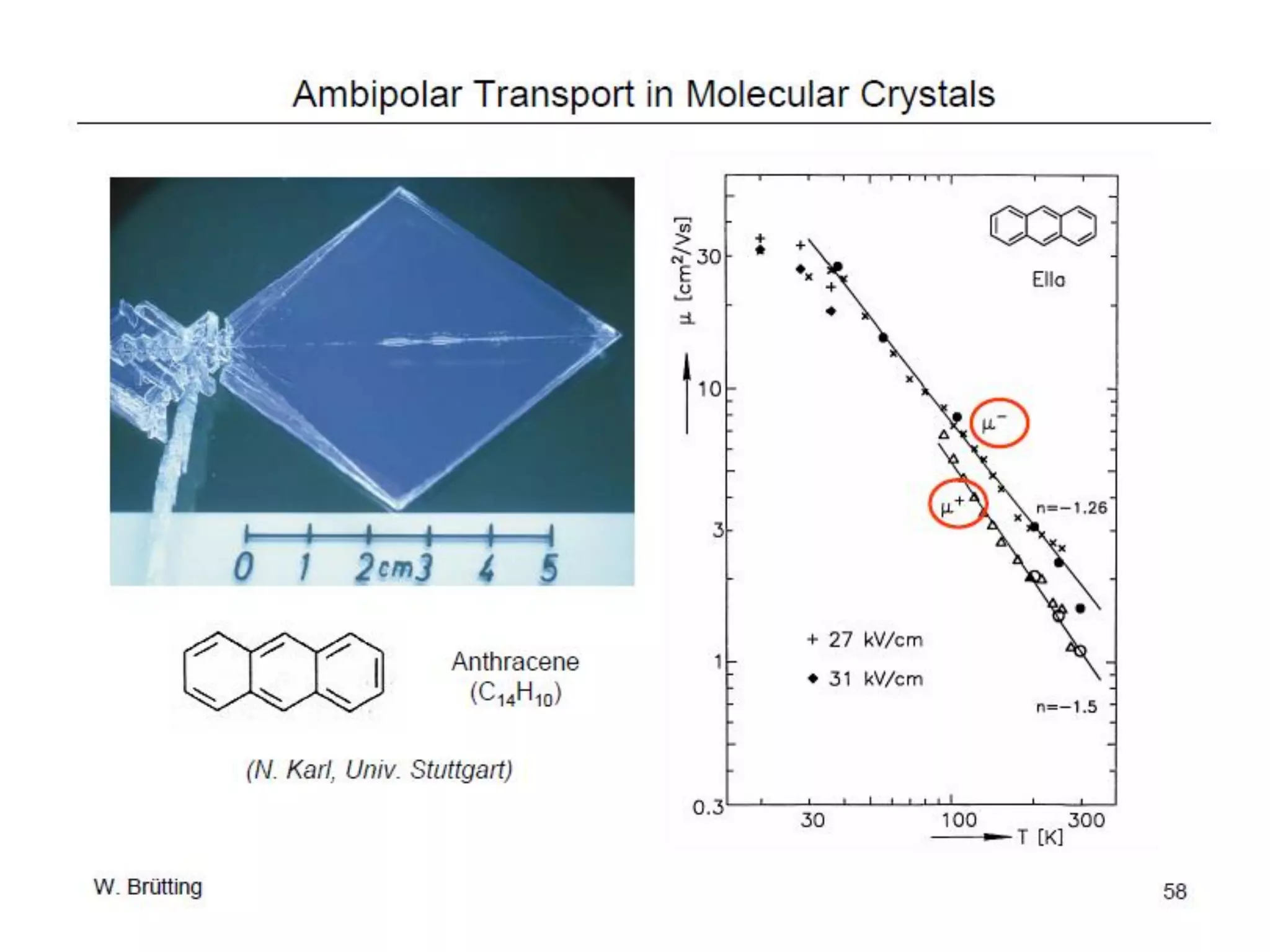

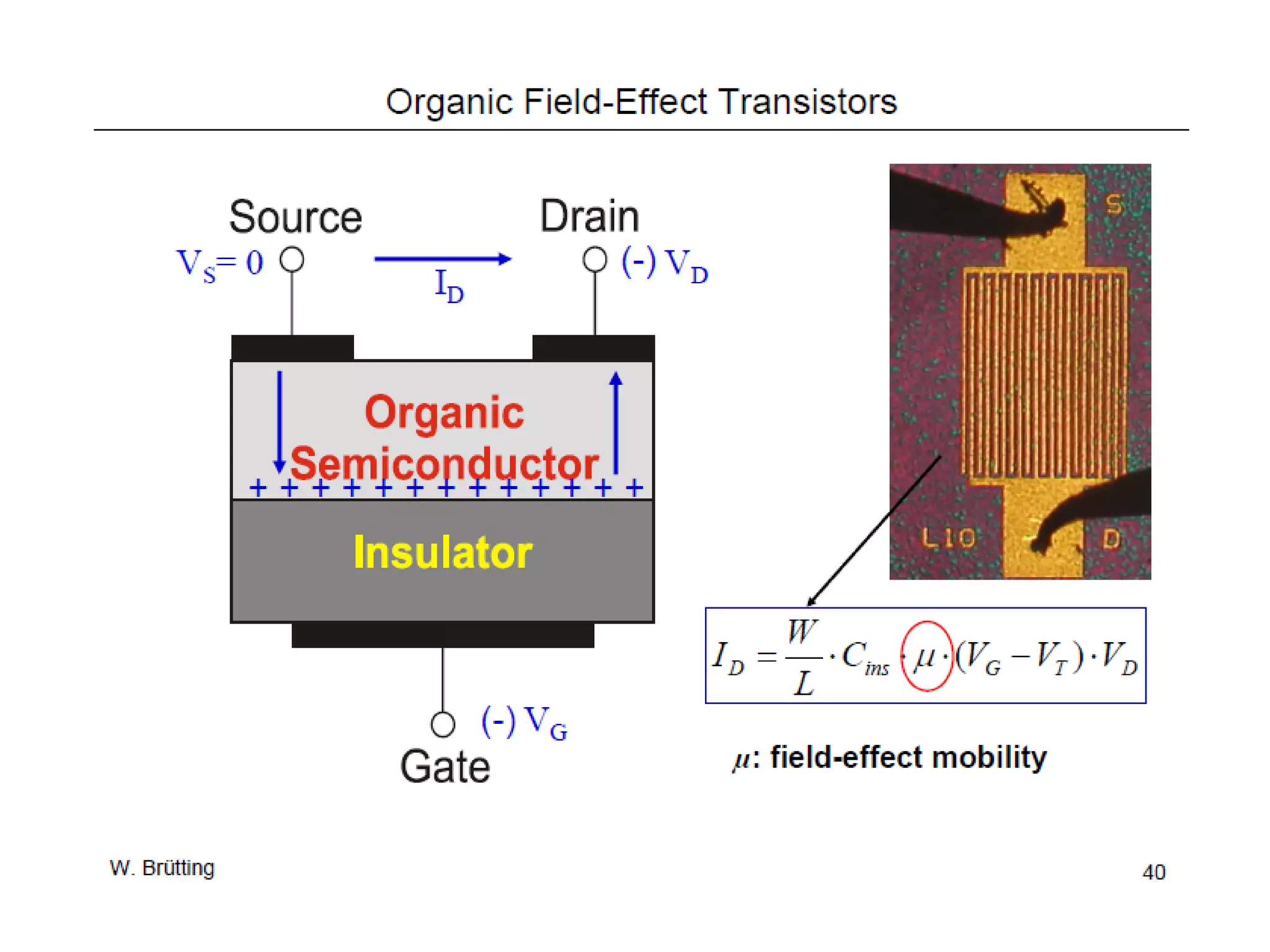

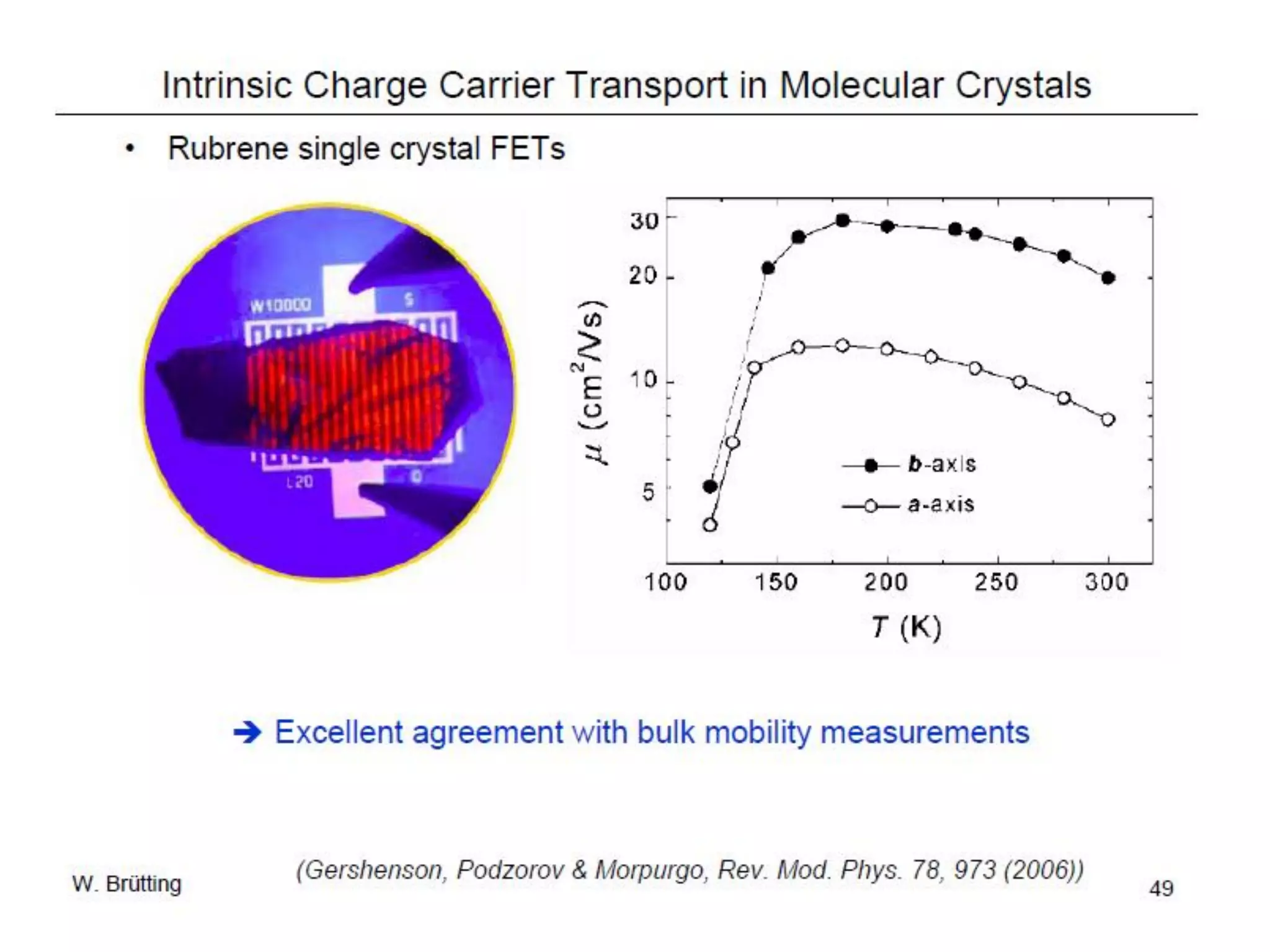

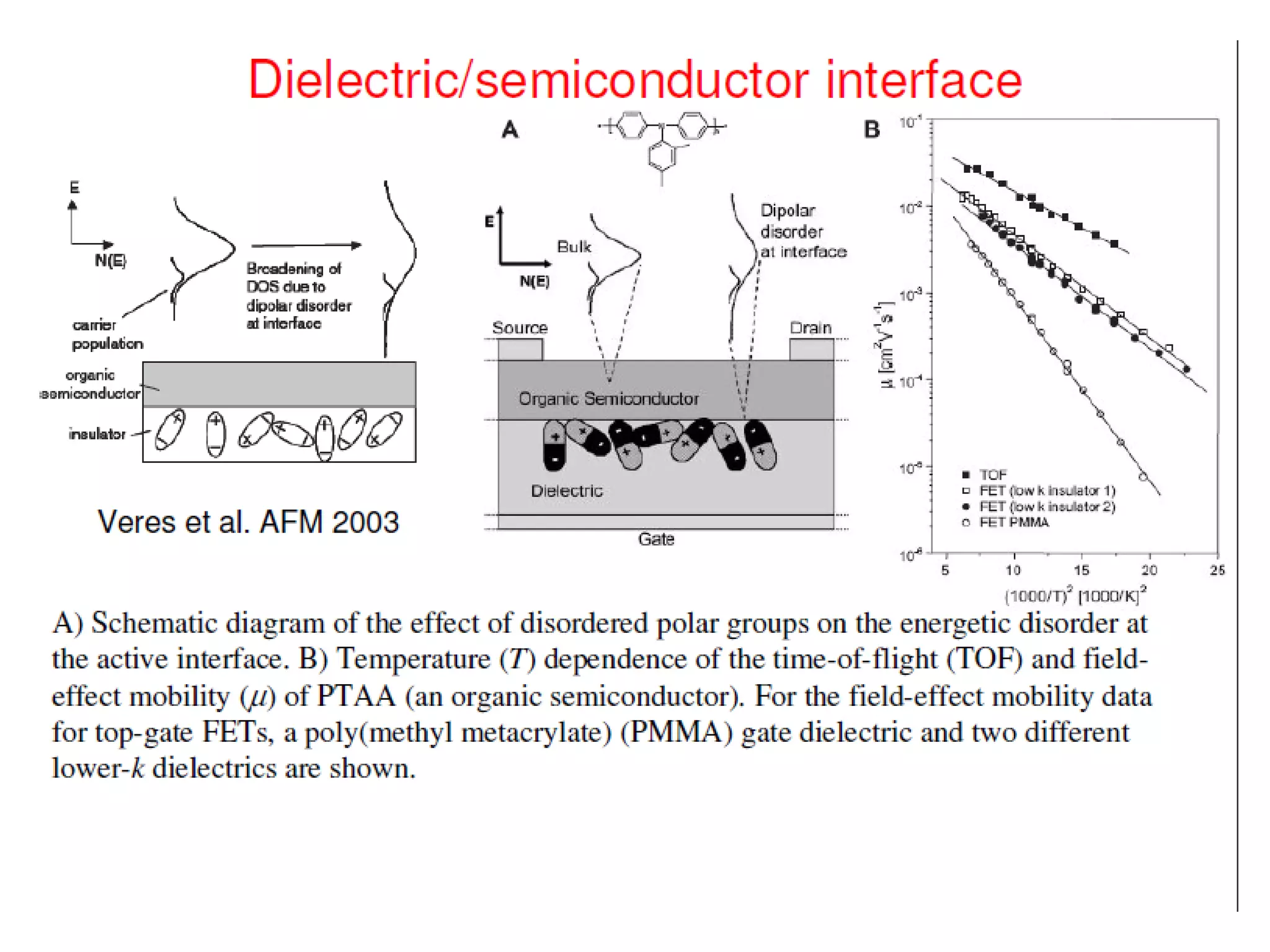

This document outlines a course on organic molecular solids. It covers topics like crystal structures of prototypical organic molecules, materials preparation techniques, and electronic properties measurements. Measurement techniques discussed include four-probe and van der Pauw resistivity measurements, Hall effect measurements, and time-of-flight measurements to determine drift mobility. The course also examines insulators, charge transport theory, excitons, organic conductors including charge-transfer complexes, and applications such as OLED displays and solar cells.