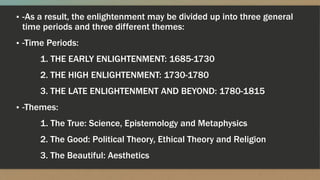

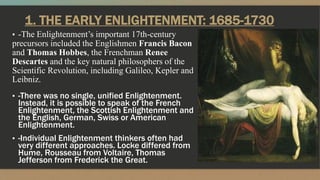

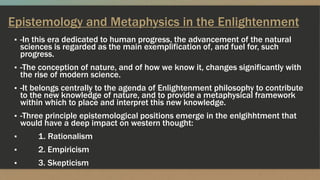

The document provides an overview of the Enlightenment period in Europe from the 17th to 19th centuries. It discusses key themes and time periods of the Enlightenment, including the Early Enlightenment from 1685-1730, the High Enlightenment from 1730-1780, and the Late Enlightenment from 1780-1815. It also summarizes major philosophical positions that emerged during the Enlightenment, such as rationalism, empiricism, skepticism, and how they influenced views of knowledge. Additionally, it outlines political revolutions and theories of the Enlightenment as well as perspectives on religion.