This document discusses the applications and efficiencies of transformers in power distribution networks, highlighting their role in electricity transmission at high voltages to reduce power loss. Transformers are noted for their high efficiency, with larger units achieving efficiencies of up to 99.8%, and the potential for cost savings through improved designs over their long lifespans. The document also emphasizes the importance of transformer design, manufacturing, and cooling methods to enhance performance and efficiency across different applications.

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 2

INTRODUCTION: WHY DO WE NEED A TRANSFORMER?

Why do we need a transformer? Electric power has to be transmitted at the highest feasible voltage if power

losses in the electricity line are to be kept within reasonable limits. This is true in absolute terms: the higher

the transmission voltage, the lower the current and hence the smaller the (resistive) power loss in the line. It is

also true in relative terms. While a 3 V voltage drop in a motor vehicle’s 12-volt on-board electrical system is a

significant loss, it would hardly be noticed in a 230 /400 V distribution network and certainly would not impair

the function of any load. In a high voltage network, the same 3-volt drop would be almost immeasurably small.

Consider a transformer of certain dimensions. Now double each of the three dimensions: length, width, and

height, while retaining the same transformer structure. Clearly, the area of any face of the transformer will

increase fourfold. This will also apply to those surfaces available for dissipating heat losses, to the cross-

sectional area of the conductors, and to the cross-sectional area of the iron core—each of which is an

important transformer design parameter. If the linear dimensions are doubled however, all volumes will

increase by a factor of eight and so will the corresponding mass.

Assuming that the current densities in the conductors remain unchanged, the current carrying capacity (or

ampacity) of the conductors will increase fourfold, since the cross-sectional area of the conductors is now four

times as great. The current density measured in all transformers rated from 10 VA to 1 GVA is indeed

approximately 3 A/mm² for copper conductors and about 2 A/mm² when the conductor material is aluminium.

However, doubling the dimensions of the wire not only increases the conductor’s cross-section by a factor

four, it also doubles its length. The eightfold increase in the volume of the conductor material mentioned

above corresponds to an eightfold increase in the mass of copper or aluminium used. For a given current

density and temperature (though the effect of temperature is not critical in this simple analysis), every

kilogram of a particular conductor material will generate the same amount of heat loss. Therefore, a

transformer whose length, width, and height have all been doubled will weigh eight times as much, and the

heat losses it generates will consequently also rise by a factor of eight. This eightfold increase in heat loss must

nevertheless be dissipated by cooling surfaces whose area is only four times as great—a fact that we ignored

above. In practical applications, larger transformers therefore need additional cooling. The first step is to

introduce liquid cooling of the transformer windings. Further cooling can be achieved by increasing the area of

the transformer cooling surfaces. This type of cooling system is known as ONAN cooling (oil natural circulation,

air natural circulation). Forced cooling is used in transformers with ratings above about 40 MVA. In this type of

cooling, known as ONAF cooling (oil natural circulation, air forced circulation), liquid cooling is augmented by

cool air blown in by fans. Above about 400 MVA, it becomes necessary to use pumps to help circulate the oil

coolant. This form of cooling is abbreviated OFAF and stands for oil forced, air forced circulation. In

transformers with power ratings greater than 800 MVA, simply circulating the oil is no longer sufficient and

these transformers use ODAF cooling (oil directed, air forced cooling) in which a jet of cooling oil is directed

into the oil channels of the transformer windings.

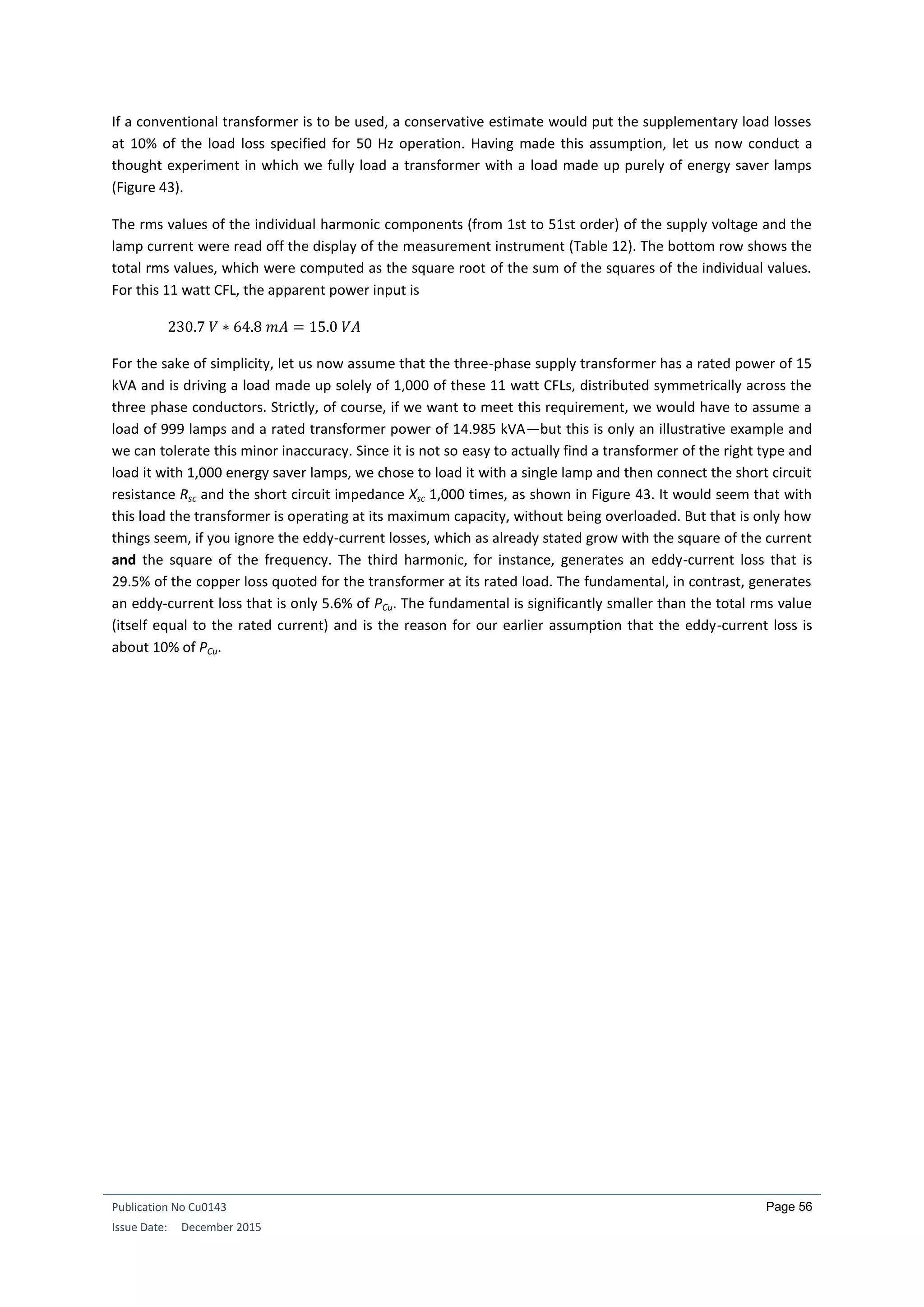

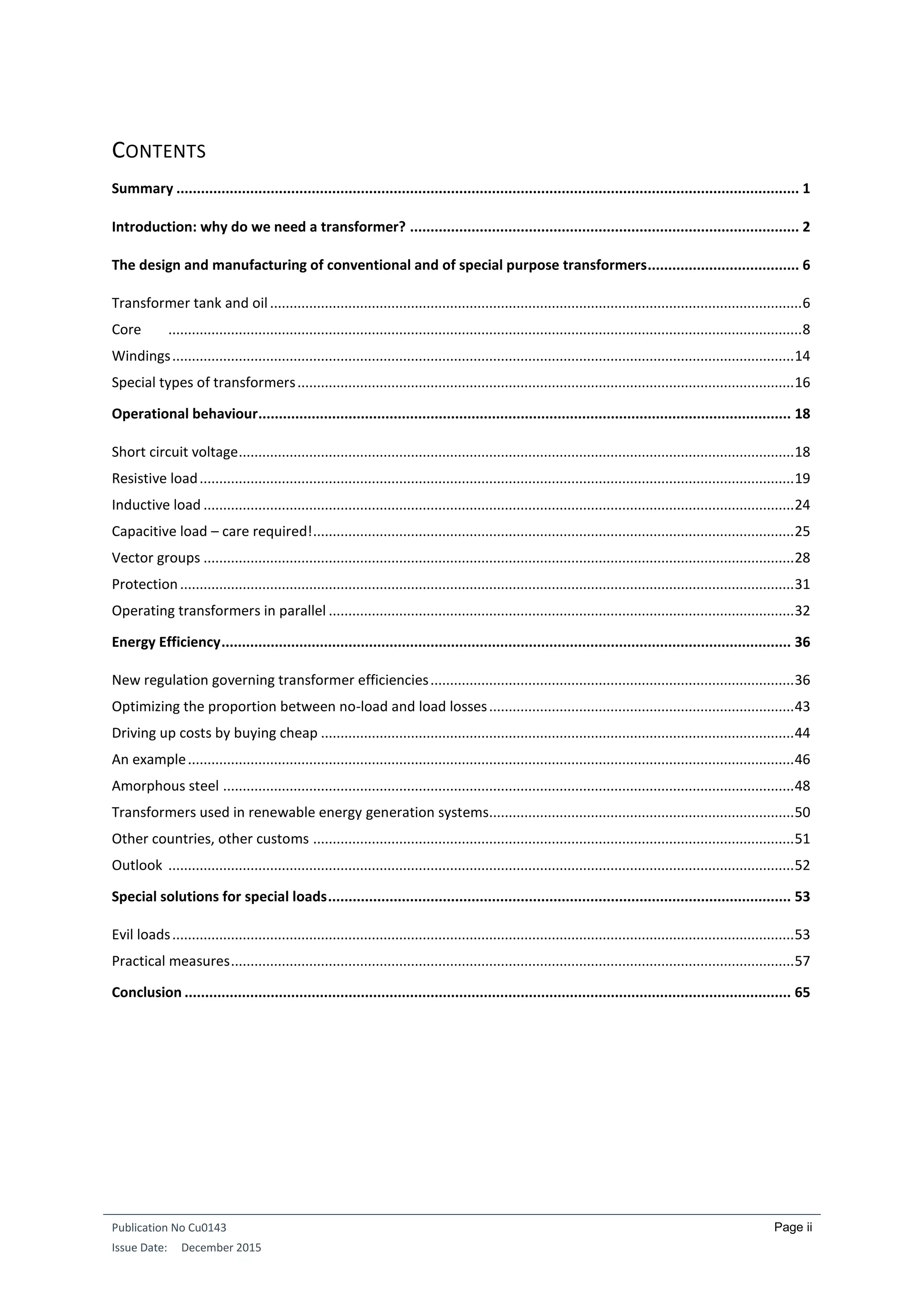

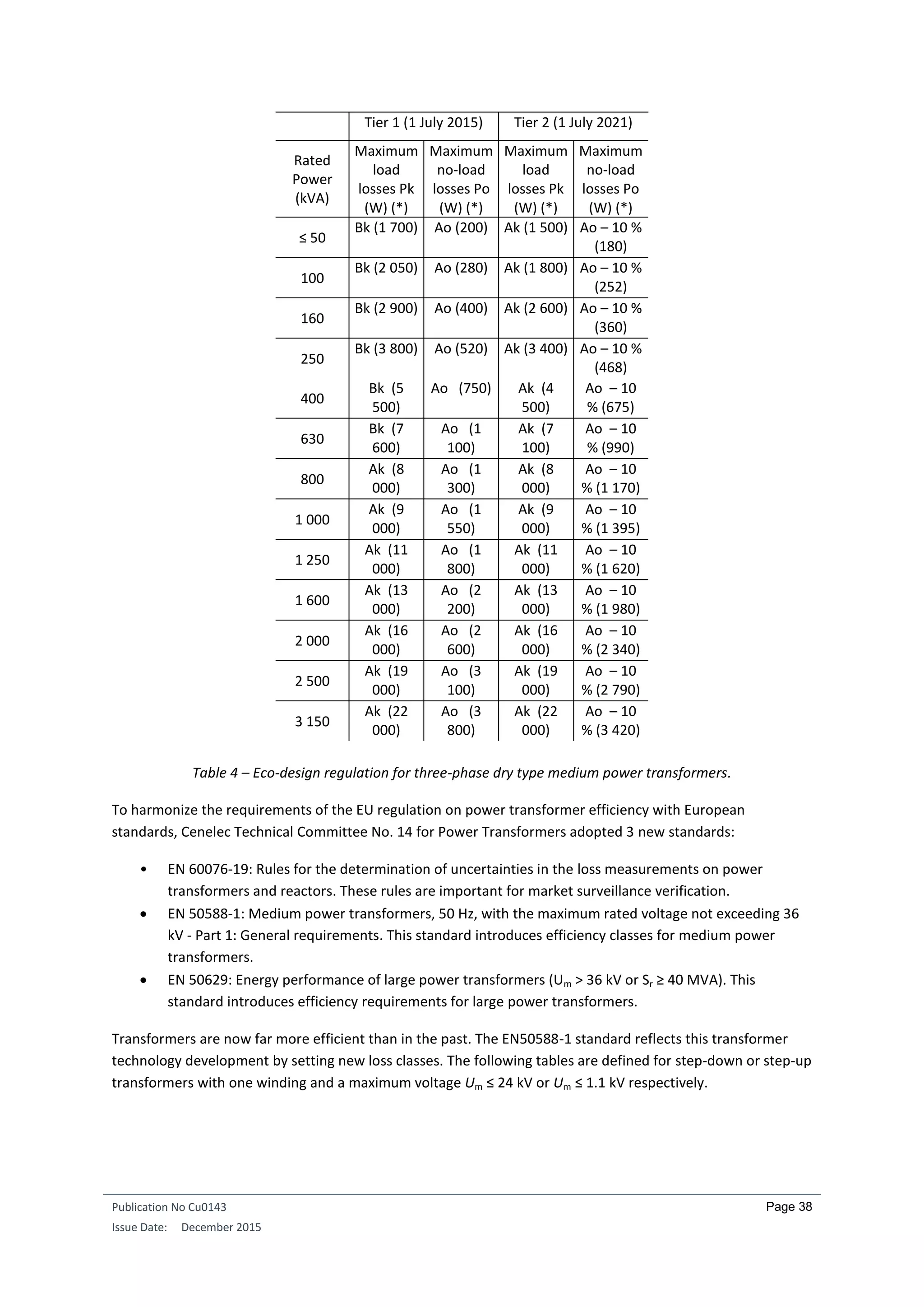

Table 1 – Power densities and efficiencies of a range of real transformers from a miniature transformer to a

generator transformer.

Example transformers

found

S [kVA] Cu [kg]

S/Cu

[kVA/kg]

S/Cu4/3

[kVA/kg4/3

]

Current

Density

[A/mm²]

Energy

Efficiency

Minimum Transformer 0.001 0.014 0.070 0.291 7.000 45.00%

Small Transformer 0.100 0.500 0.200 0.252 3.000 80.00%

Industrial Transformer 40.000 48.200 0.830 0.228 3.397 96.00%

Distribution Transformer 200.000 200.000 1.000 0.171 98.50%

Bulk Supply Point Transformer 40000.000 10000.000 4.000 0.186 3.000 99.50%

Generator Transformer 600000.000 60000.000 10.000 0.255 99.75%

Geometric Mean Value --- --- --- 0.227 --- ---](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-5-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 19

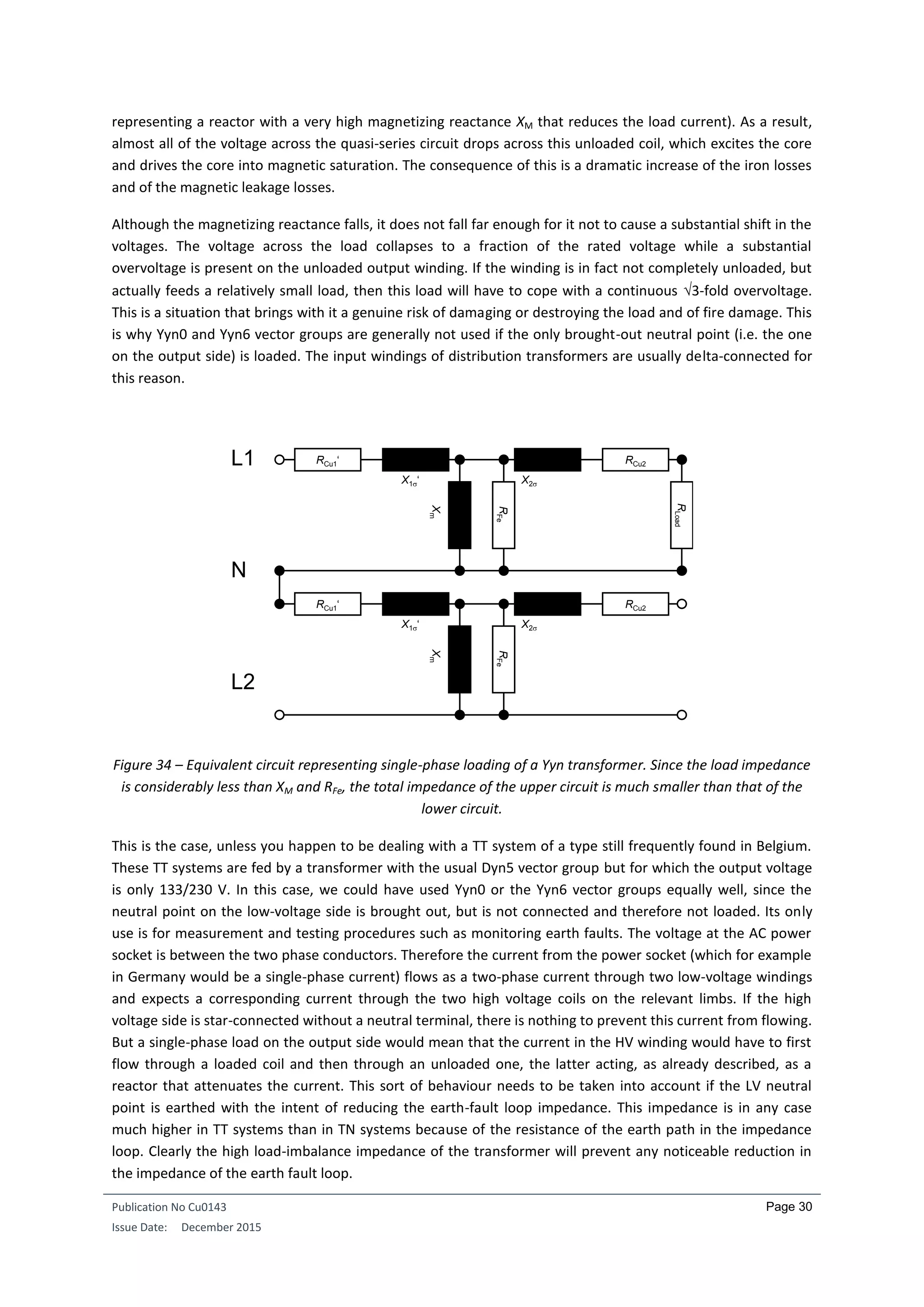

The short circuit voltage thus characterizes the voltage drop within the transformer. If the short circuit voltage

is known, the short circuit current Isc can be readily calculated. For example, if all upstream impedances are

ignored, the short circuit current in a transformer with usc = 6% is:

𝐼𝑆𝐶 =

𝐼 𝑁

𝑢 𝑠𝑐

=

𝐼 𝑁

6%

≈ 16.7 𝐼 𝑁

For a transformer with usc = 6%, six percent of the rated input voltage is therefore needed to generate the

rated (nominal) current IN in the short-circuited secondary winding. However, only a small part (uR) of the

voltage drop in a medium-sized distribution transformer is due to the ohmic resistances in the windings. The

largest factor contributing to the voltage drop is by far the reactive/inductive voltage drop uX. This stems from

the leakage inductance caused by the portion of the magnetic flux that bypasses the core (leakage flux) and

permeates only a single winding. This leakage flux does not flow in the primary and secondary windings

simultaneously. Rather it flows in the main leakage channel between the high voltage winding, which is

generally located on the outside, and the low-voltage winding on the inside [c.f. Section 2 Design]. The leakage

flux is therefore part of the magnetic flux of the outer but not the inner winding. This also has the incidental

effect that the short circuit voltage cannot be influenced by the non-linearity of the iron core. uX is also

referred to as the leakage reactance voltage. The principal function of the main leakage channel is cooling; its

secondary function is insulation. In addition, it also serves to maintain the so-called leakage reactance, which is

in effect a defined short circuit voltage.

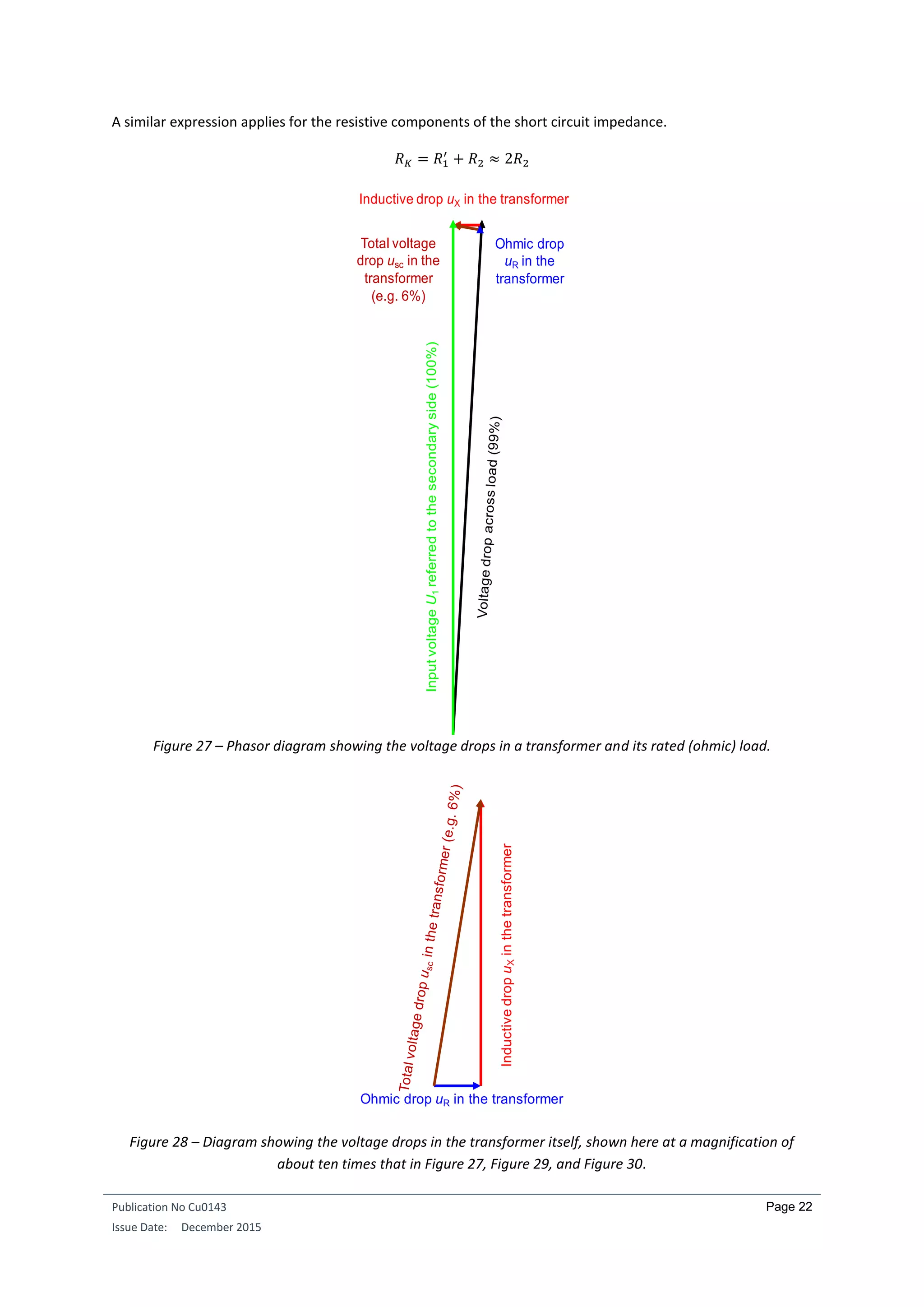

As shown in Figure 28, the sum of the squares of the inductive voltage drop uX and the ohmic voltage drop uR

equals the square of the overall voltage drop usc (c.f. Pythagoras’ theorem concerning the sides of a right-

angled triangle). Fortunately, the ohmic voltage drop uR is, as already mentioned, the smaller portion. The

larger the transformer, the smaller this is. A simple calculation proves this point: If a transformer in the 630

kVA range has an efficiency of 98.5% when operating at its rated load, then the total ohmic voltage drop across

the two windings can be no more than 1.5% of the rated voltage. In practice however, the value is lower, for

example 1%, because the 1.5% includes losses other than the ohmic losses in the coils. Our usc of 6% is

therefore made up of uR = 1% and uX = 5.91% of the rated voltage (6² =1² + 5.91²).

RESISTIVE LOAD

A transformer’s power rating is always specified relative to its resistive load. The ohmic resistance of the

winding contributes linearly to the (rated) load, while the inductive resistance (reactance) of the leakage

inductance contributes quadratically. Therefore the resistance of the winding contributes only 1% to the load

resistance, with the remaining 5.91% having only a negligible effect on the total voltage drop across the

transformer and the load. We now want to determine precisely how small this effect actually is.

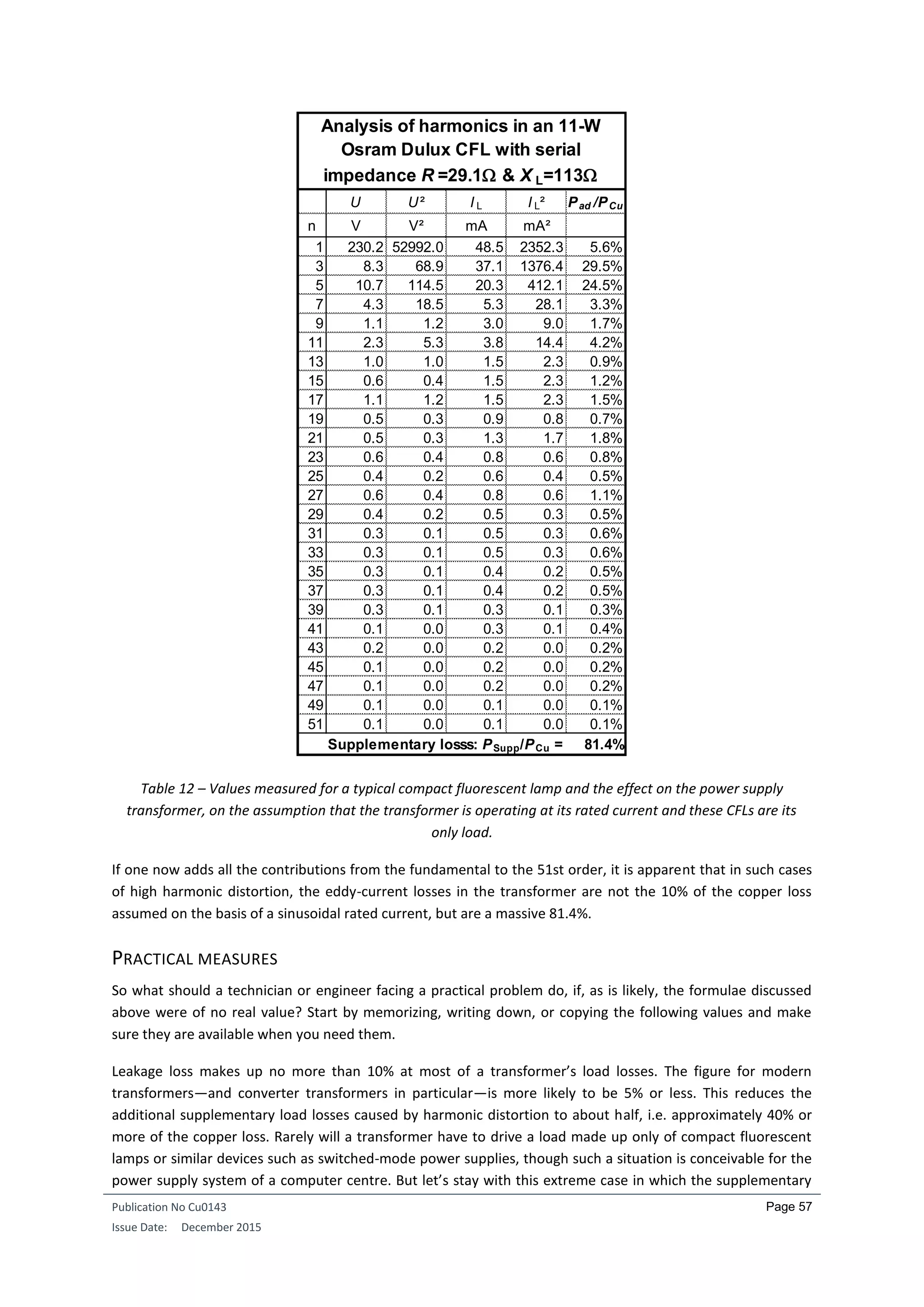

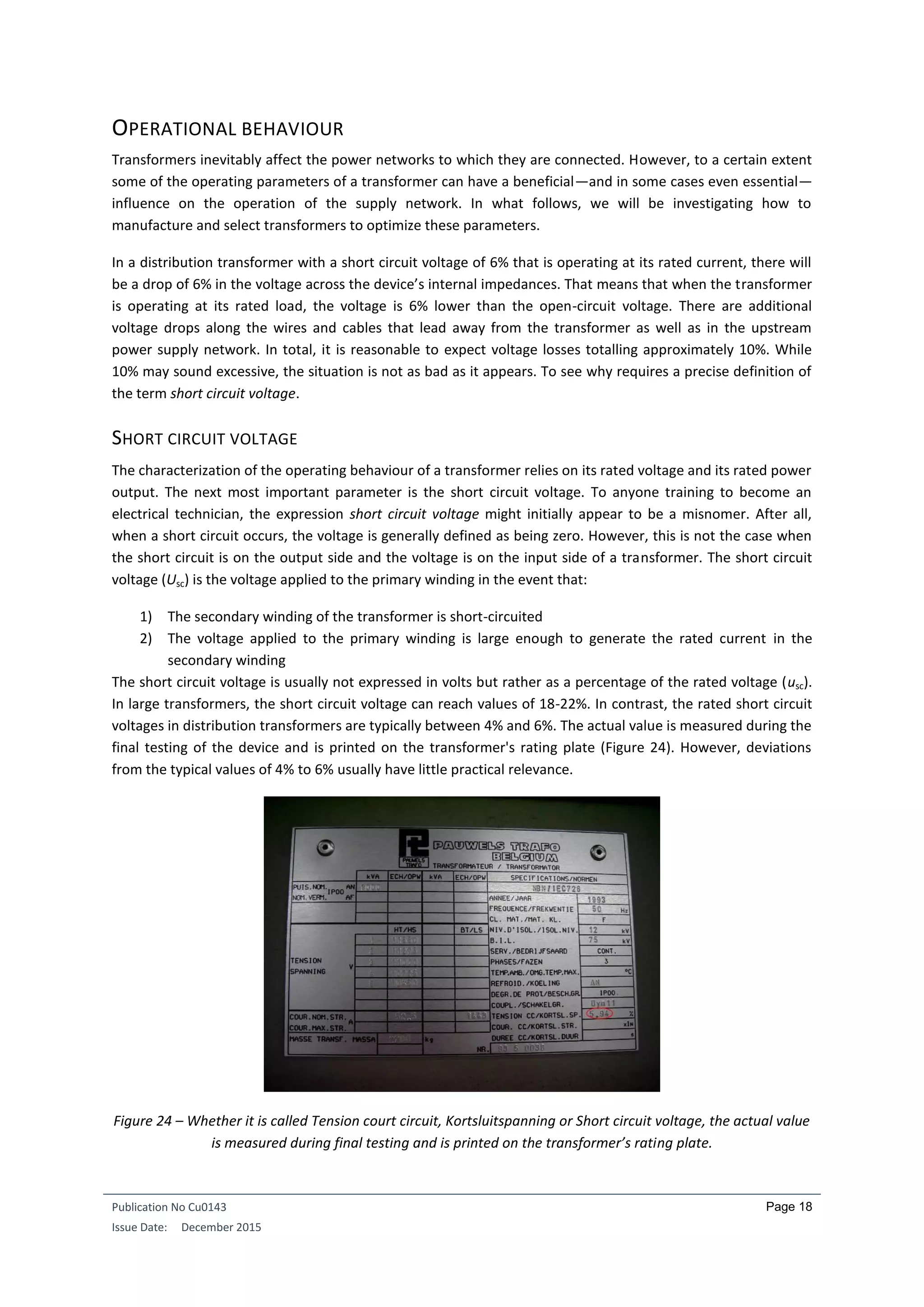

The non-ideal behaviour of a transformer can be illustrated by an equivalent circuit model (Figure 25). The

model assumes that the input and output windings have the same number of turns. As this is obviously not

usually the case, the values associated with one side of the transformer are moved (i.e. referred) to the other

side by multiplying them by the ratio of the number of turns on the two windings. The behaviour of the

transformer can then be calculated for the relevant reference side. In Figure 25, all elements have been

referenced to the load (i.e. secondary) side.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-22-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 25

lived for a time next to a building site where a tower crane has been operating (without power-factor

correction) will know exactly what this refers to

1

. Luckily, mobile units are now available that can be used to

counteract such flicker sources

2

.

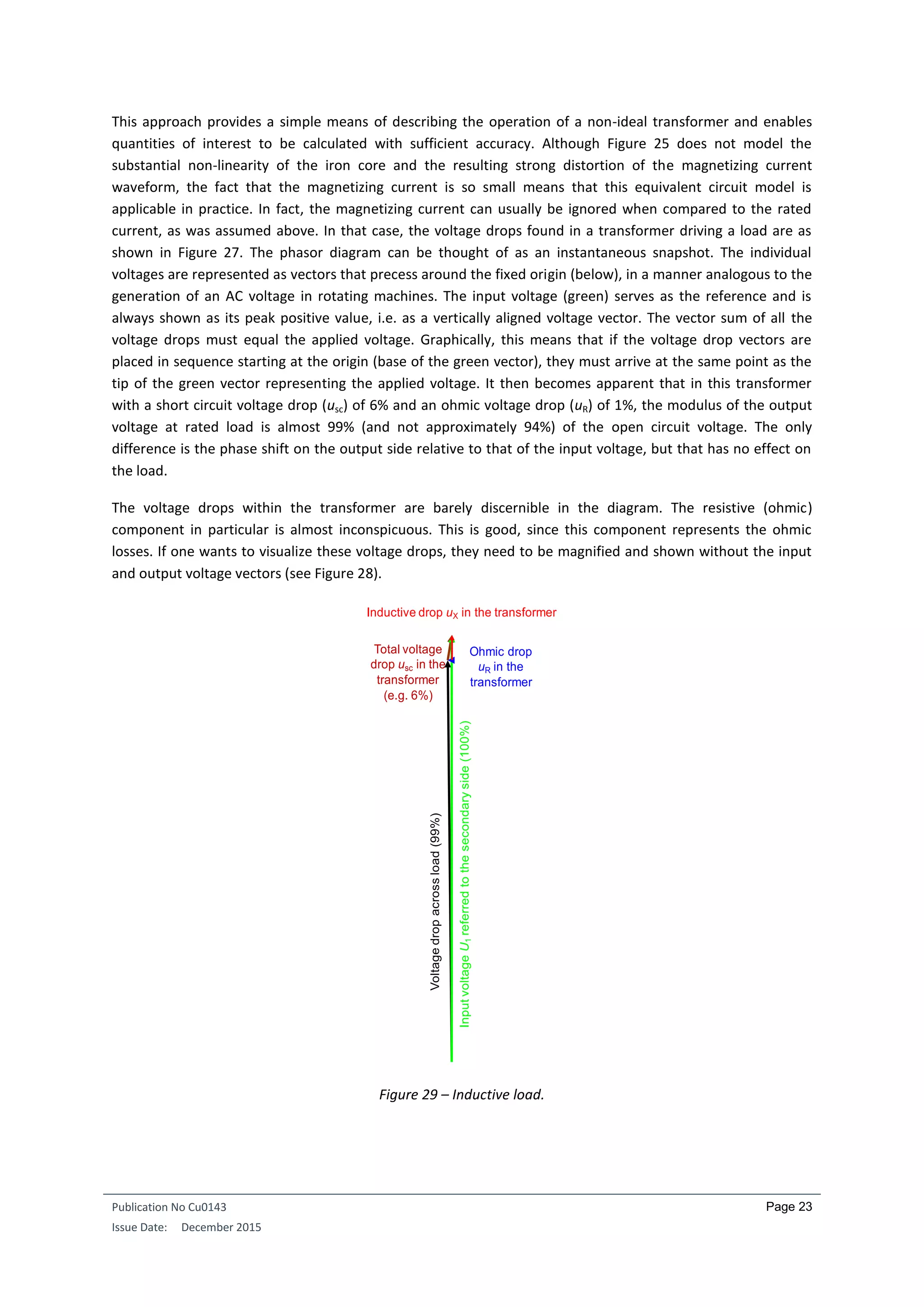

The same approach can be used to determine whether the primary cause of the voltage drop at a domestic

power socket is the leakage inductance of the distribution transformer or the ohmic resistance of the power

cables. For instance, when a fan heater with a current input of 9 A is operating, the voltage at a particular

power socket is found to decrease from 230.7 V to 226.3 V. If a large inductive load that draws over four times

as much current (see Figure 27) is connected, we see that there is no discernible increase in the voltage drop.

With reference to the phasor diagrams shown in Section 3.2, it can be concluded that the ohmic resistance is

by far the larger component—at least in the case of this particular cable and transformer. However, this test

must be performed with great caution. Since this test involves a substantial overload, the duration of the test

must be kept short. Failure to do this will trigger the 16-ampere circuit breaker, which is normally rated for a

power factor range from 1 to 0.6. A circuit breaker is not really the best means of switching off what is

essentially a purely inductive load.

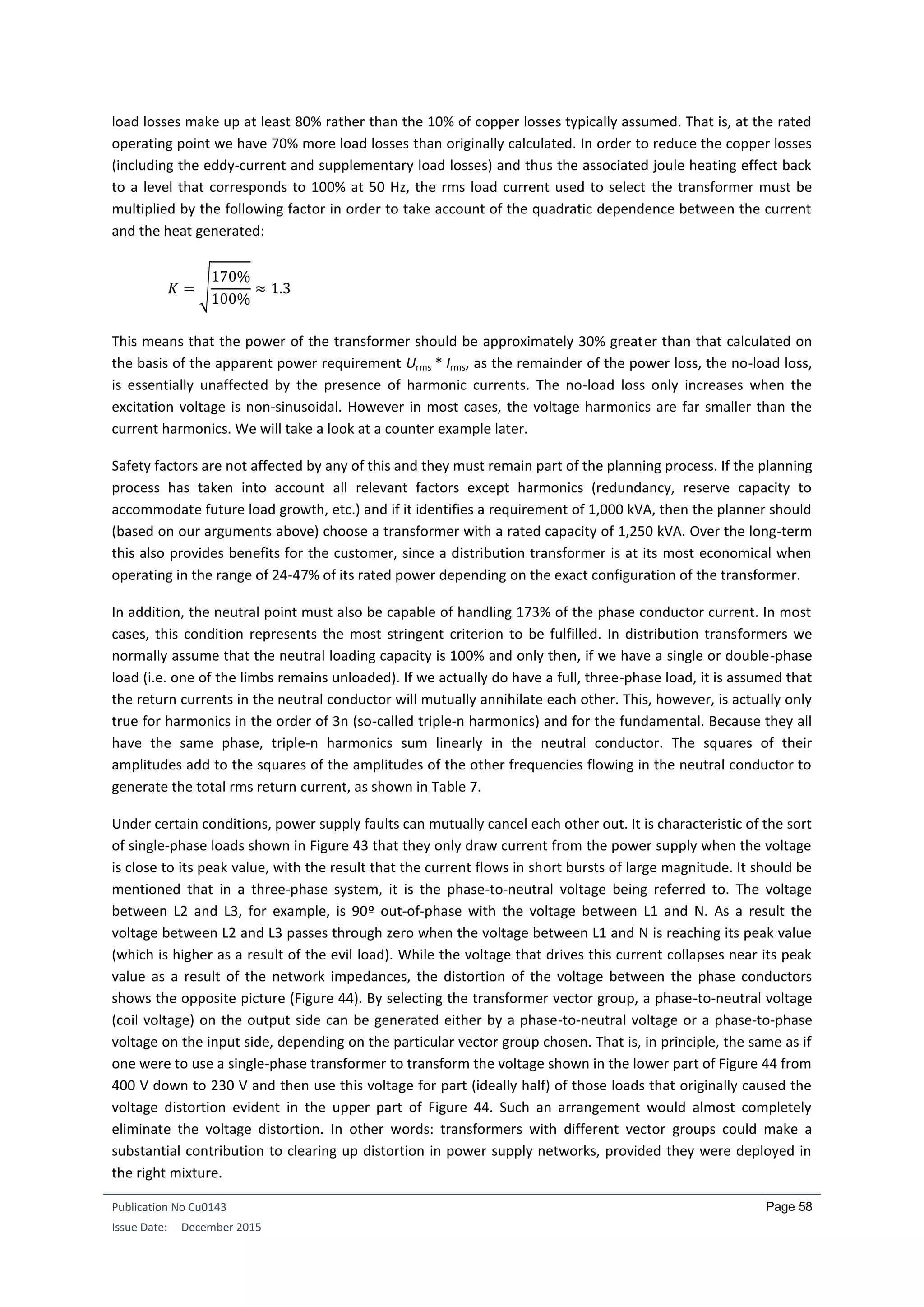

Figure 31 – Large inductive load on a domestic power socket.

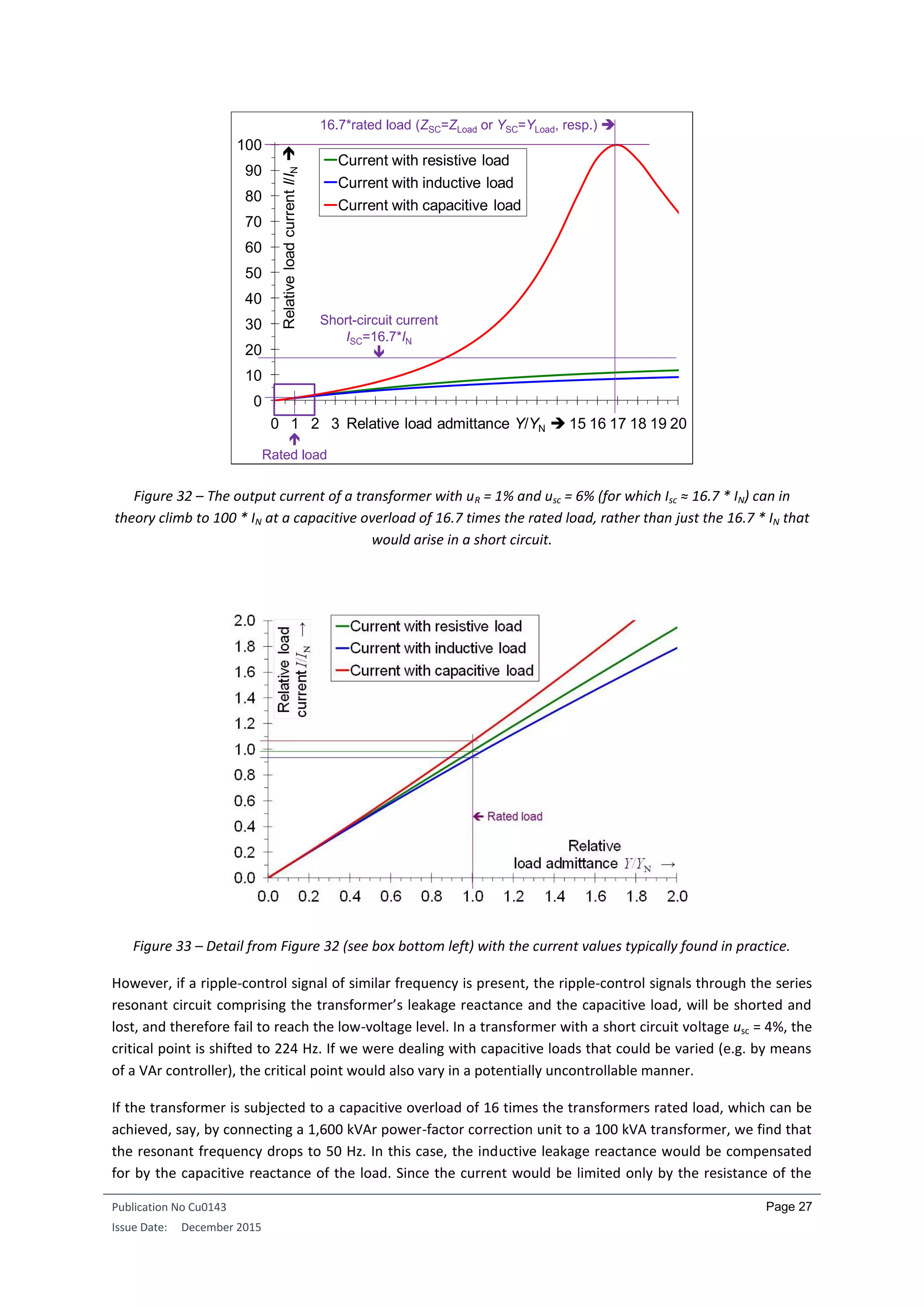

CAPACITIVE LOAD – CARE REQUIRED!

Things get really exciting when dealing with capacitive loads. In principle, this is the situation described earlier

in which the transformer is excited from the output side, i.e. compensation of the inductive magnetizing

reactive power by the capacitive load. If the load is so small that it is just sufficient to provide compensation,

then only the transformer will be excited—a perfectly normal situation, irrespective of the winding. The

picture changes however, as the capacitive load increases. The passage of the load current through the

leakage reactance results in a voltage drop with a phase lead of 90°. Its passage through the capacitive load is

accompanied by a voltage drop lagging by 90°. In other words, these two voltage drops have opposite signs

and therefore subtract from one another rather than add. At 100% of the rated input voltage, we have a

1

Fassbinder, Stefan: Netzstörungen durch passive und aktive Bauelemente, VDE Verlag, Berlin / Offenbach

2002, p. 188

2

Bolliger, R.: Wenn die Lichter flackern [‘When the lights flicker’]. ET Schweizer Zeitschrift für angewandte

Elektrotechnik 11/2003, p. 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-28-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 34

still—introducing system redundancy by including a pair of 630 kVA transformers, each of which is capable in

an emergency of handling the load on its own. Having reserve capacity also helps to settle the nerves. First,

conversion or retrofitting costs are far lower if there is a need to handle greater loads at some later date.

Secondly, power losses are reduced and, thirdly, the voltage drop in the transformer is lower as a result of

using either two 630 kVA devices in parallel or from using a single large device. Indeed this can be the

optimum solution for flicker problems since it gets things right at the start rather than attempting to deal with

the problem by grafting on a solution later

5

. Of course, the price for this improved resistance to flicker in the

supply system is a higher short circuit power. The short circuit power rises linearly with the size of the

transformer (provided the rated short circuit voltage is constant) and is the sum of the short circuit powers of

the individual transformers if they are connected in parallel. This needs to be considered when configuring the

downstream distribution network.

The term short circuit power needs to be used with care. According to the definition, the short circuit power is

calculated by multiplying the open-circuit (i.e. no-load) voltage by the short circuit current. The operating

states no-load and short circuit are however mutually exclusive. Short circuit power is a purely fictional

computational parameter, but never-the-less one that is useful in estimating what could happen in the event

of a short circuit.

There is one further and very obvious condition for operating transformers in parallel: the vector group codes

of the units to be connected in parallel must be the same. The important aspect here is that the digits

following the letter codes are identical. If they were not the same, one would end up connecting windings with

different phase relationships—a situation that is obviously unacceptable. For instance, two transformers with

the vector group codes Dd0 and YNyn0 can certainly be operated in parallel. But if the neutral point is loaded,

the single-phase or non-linear load will be borne by only one of the transformers, since the other does not

have a neutral point. This needs to be taken into consideration. Additionally, the short circuit voltages on the

rating plates refer to symmetric, linear, three-phase loads. If another type of load is connected, quite different

values will apply. The size of the deviation will then depend strongly on the vector groups involved

6

. By this

point, things can have begun to get quite confusing. Connecting transformers with different vector groups in

parallel is certainly not to be recommended, and should only really be seen as an emergency measure.

When we discuss operating transformers in parallel, we normally mean that the output sides are connected in

parallel, as the input sides are usually connected either directly or indirectly in parallel. It is possible, however,

that a distribution transformer is fed from different MV systems, which in turn are fed from the same HV

system but via HV transformers with differing vector group codes (and therefore having different phase

relationships). In this case, the sum of the vector group code digits for the HV transformer and the

downstream distribution transformer must be the same for each HV transformer so that the voltages at the

secondary windings have the same phase.

But as is so often the case, that’s not quite the whole truth. Vector group codes are not the only significant

elements. We also need to take the power transmission networks into account. The case capacitance (i.e. the

5

See [1], p. 51

6

Fender, Manfred: Vergleichende Untersuchungen der Netzrückwirkungen von Umrichtern mit Zwischenkreis

bei Beachtung realer industrieller Anschlußstrukturen [‘Comparative studies of the effects of converters with

intermediate circuits on power quality in real industrial installations], Ph.D. thesis, Wiesbaden 1997](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-37-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 35

capacitance per unit length)

7

of underground cable is very large, while its series inductance (i.e. inductance per

unit length) is rather small. In overhead power lines, on the other hand, the capacitance is smaller and the

inductance is greater. Phase relationships will therefore vary depending on the specific load conditions.

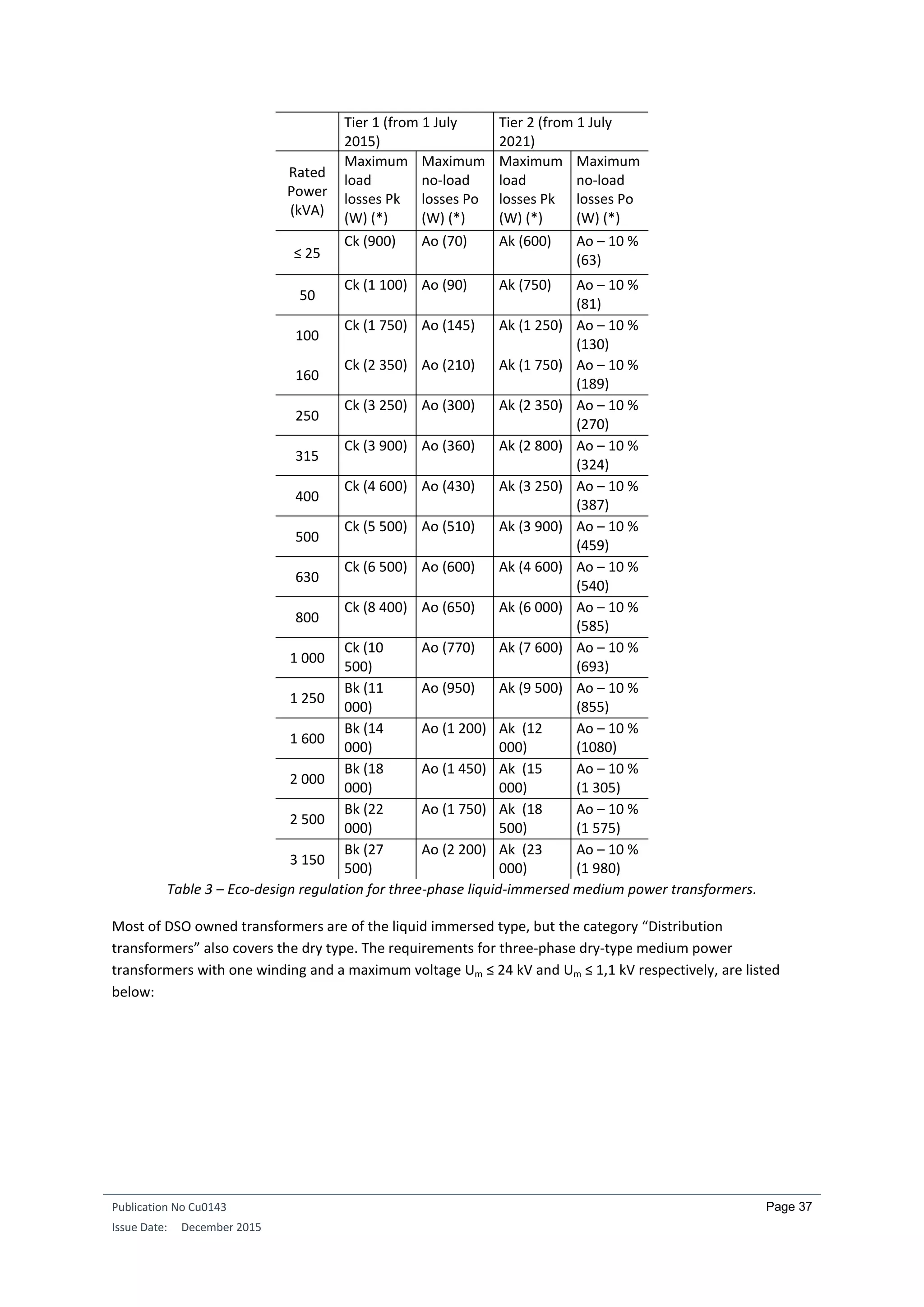

Let us assume that we have two distribution transformers that are connected in parallel on their output sides.

They have the same rated outputs, the same vector groups, the same short circuit voltages, the same output

voltages, and even approximately the same copper losses. In other words, they are ideally suited to be

operated in parallel. One of the transformers is fed via a relatively long underground MV cable, the other via a

relatively long overhead MV line. As we assume that the voltages supplied at the start of the two cables have

the same phase and the modulus of the impedance is similar for the two cables, it is reasonable to expect that

there will not be any appreciable imbalance in the distribution of the common load. However, the phases of

the voltages arriving at the input sides of the two parallel distribution transformers (i.e. at the ends of the MV

supply cables) can indeed be different. The phase relationships measured at the LV bushings are therefore also

different and if the bushings are connected in parallel, a circulating current will begin to flow and the two

transformers will appear to heat up even under open circuit (no-load) conditions. However this is not actually

the case since the transformers are not really under no-load conditions. In fact, they drive the circulating

current. The power losses are almost purely reactive in nature. The only exception is the ohmic losses in the

two transformers as well as in their connection cables on the high voltage and low-voltage sides as far as the

coupling points.

The underground cable also represents a substantial capacitive load for the HV feeder transformer and, as

already described, this can cause an increase in the output voltage (Figure 33). In contrast, the capacitance of

the overhead line is probably small enough to be compensated (at least at full load) by the leakage inductance

of the distribution transformer that is being fed. The voltages can therefore differ not only in terms of their

absolute magnitudes but also with respect to phase. The question of whether this difference could become

critical is something that has to be calculated for a wide range of load cases during the planning phase. That is

not as simple as it sounds, given the large number of transformer and supply system parameters that need to

be taken into account.

Summary: Conditions for operating transformers in parallel

Same voltage across the windings to be connected in parallel

Same rated short circuit voltages

Same vector group codes

Ensure supply networks have the same phase relations

If the transformers are not connected in parallel on the input side, ensure that the supply networks

have approximately the same short circuit power levels

Maximum size ratio of transformers operated in parallel: 3:1

7

Fassbinder, Stefan: ‘Erdkabel kontra Freileitung’ [‘Underground vs overhead power transmission cables’], in

de, vol. 9/2001, p. gig9, appears in DKI reprint s180 ‘Drehstrom, Gleichstrom, Supraleitung – Energie-

Übertragung heute und morgen’ [‘Three-phase AC, DC and superconducting systems – Power transmission now

and in the future’] from the German Copper Institute (DKI), Düsseldorf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-38-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 36

ENERGY EFFICIENCY

In 1999, the Swiss journal Bulletin SEV/VSE

8

carried a cover story entitled Replacing old transformers pays off

9

.

The article showed that as a result of the significant improvements in the efficiency of modern transformers,

there are now sound economic reasons (in addition to important environmental arguments) why older

transformers should be decommissioned even when they are still functioning properly. In this section, we

explain how these efficiency improvements have been achieved and their current and future significance for

those responsible for purchasing and deploying transformers.

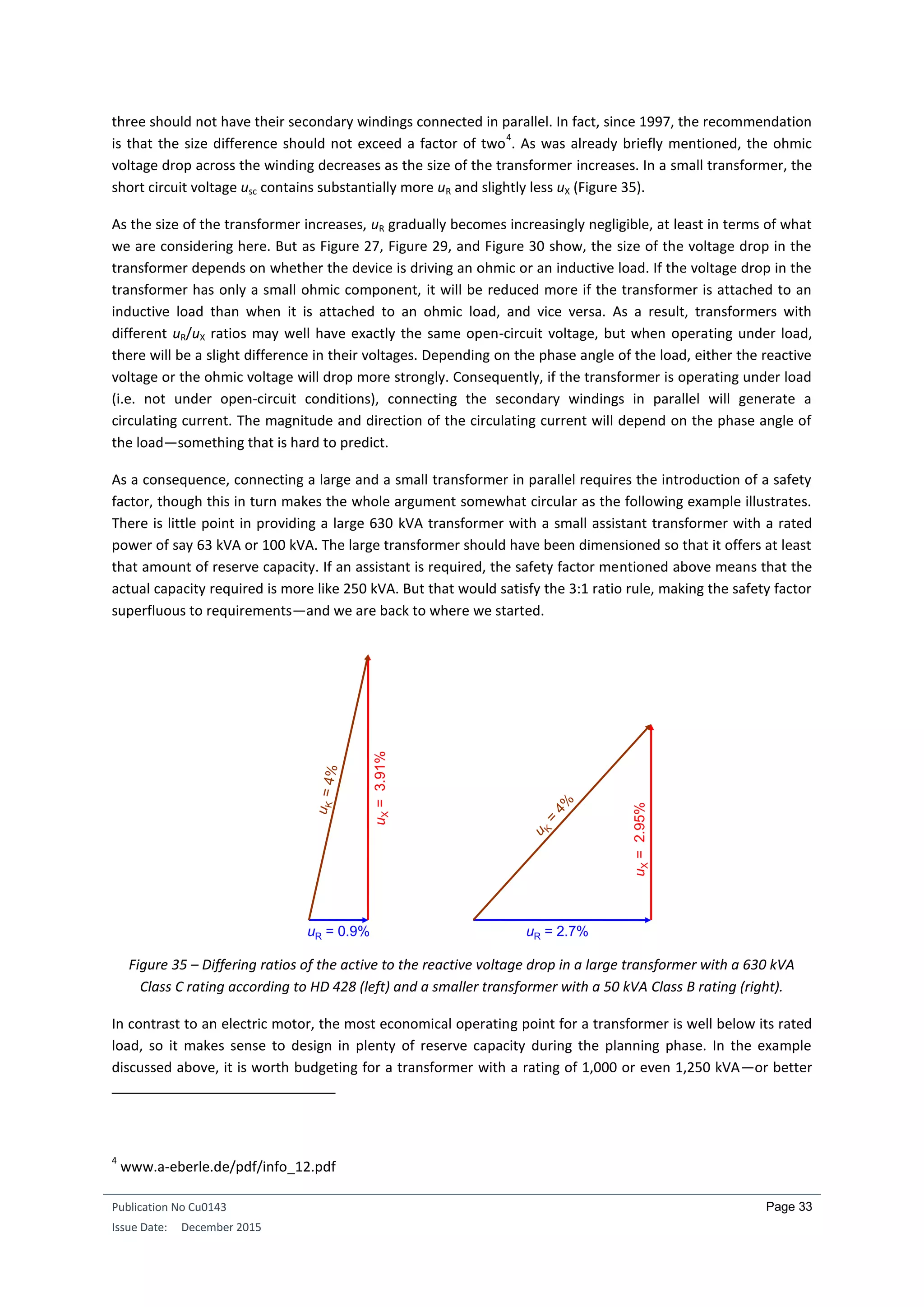

NEW REGULATION GOVERNING TRANSFORMER EFFICIENCIES

On July 1st 2015 the new European Regulation N 548/14

10

on power transformers entered into force. This was

a world premier of a regulation stipulating a minimum energy performance for large power transformers.

The regulation establishes eco-design requirements for power transformers with a minimum power rating of 1

kVA used in 50 Hz electricity transmission and distribution networks or for industrial applications. The

regulation indicates that transformers are strategic assets in the electrical networks, playing an important role

in achieving the ambitious energy efficiency targets set by most industrialized countries. Considering Europe

only, 16.7 TWh (corresponding to 3.7 megatons of CO2) will be saved in 2025 through the reduction of no-load

and load losses of transformers falling under this regulation.

The requirements for distribution transformers are formulated in the form of maximum load and no-load

losses (in W).

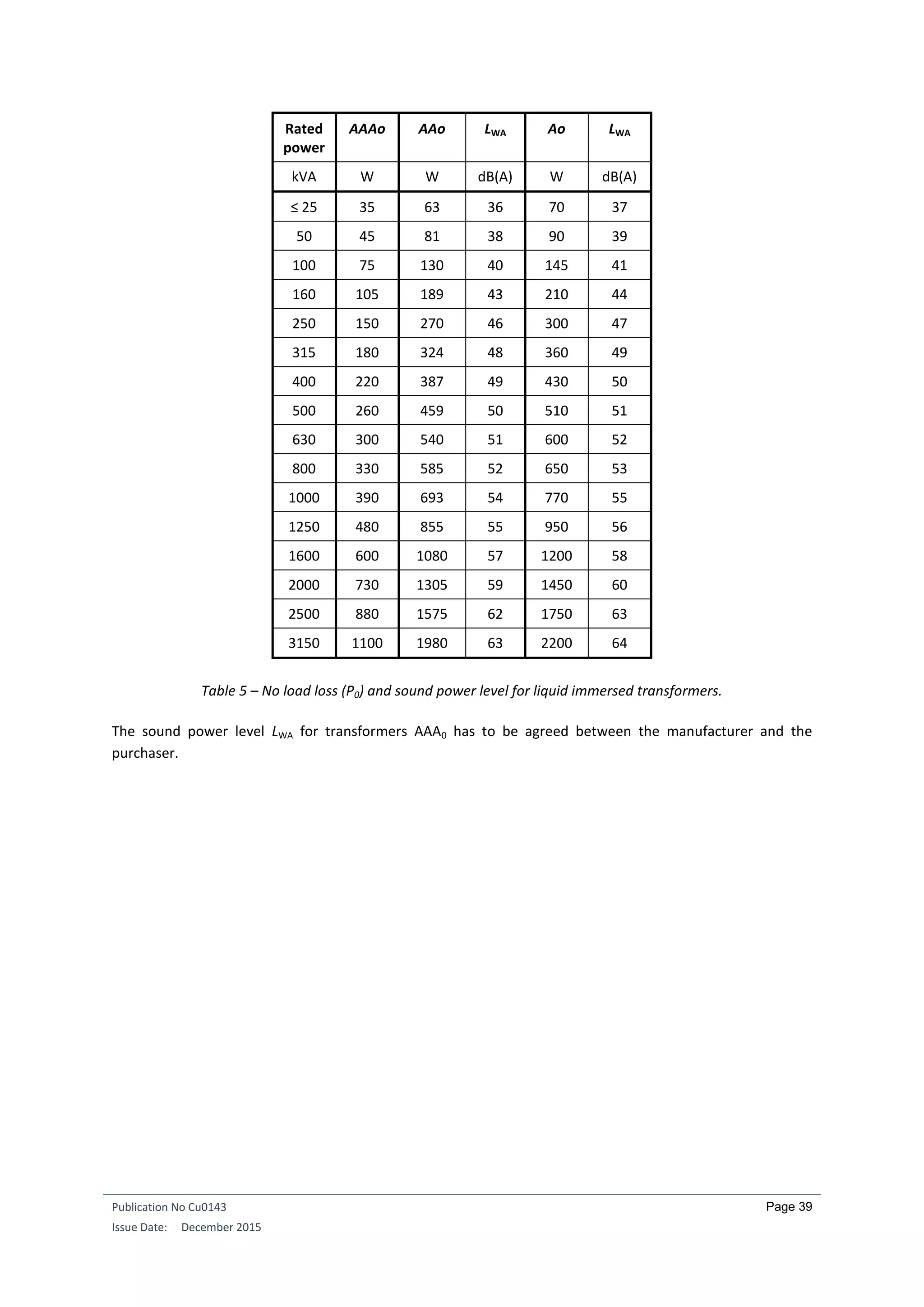

Requirements for three-phase liquid-immersed medium power transformers with one winding are listed

below, for respectively Um (maximum voltage) ≤ 24 kV and for Um ≤ 1.1 kV:

8

SEV/Electrosuisse: Swiss Association for Electrical Engineering, Power and Information Technologies

VSE: Association of Swiss Electricity Utility Companies

9

Borer Edi: ‘Ersatz von Transformatoren-Veteranen macht sich bezahlt’ [‘Replacing old transformers does

pay’], in Bulletin SEV/VSE, vol. 4/1999, p. 31

10

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2014:152:FULL&from=EN](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-39-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 45

higher, and the transformer generates correspondingly more heat in the electrical system to which it is

connected.

The best that can be said about this practice is that the transformer is a little smaller in size. But that is its sole

advantage and even that benefit can be lost because the higher temperatures generated mean that other

components have to be kept further away from it. Furthermore, the higher losses often require more effort

and expense to be spent on managing heat dissipation. The voltage drop is also larger. It is essential that

transformer professionals rid themselves of the ludicrous notion, which, when expressed provocatively, might

be phrased: ‘my transformer is better than yours, because it’s hotter.’ If progress means stepping up from

class H (with a continuous duty temperature rating of 180º C) to class C (220º C) then the heat really will be on.

How did this mind-set arise? Price pressure is the usual reason cited, with price meaning only the purchase

price and all follow-up costs conveniently ignored. But that would imply that market forces should have

eliminated any manufacturer offering more expensive devices. There are however a number of transformer

manufacturers who have decided to put quality first, and who are thriving as a result, despite the fact that the

first thing the customer is usually interested in is the price. The key here is to carefully explain to the customer

why the coil former is always fully wound, why these transformers are usually somewhat more expensive, and

occasionally significantly more expensive than apparently equivalent competitor products, and why using the

cheapest transformer usually leads to the most expensive system overall. The commercial success of these

companies

11

is clear proof that they are indeed managing to convince their clients that the purchase price of a

transformer is not its most important feature.

One manufacturer uses only grain-oriented sheet steel in the cores of all its transformers with a power rating

above about 1 kVA. This may well be due to the fact that the company uses some of these (auto)transformers

in one of its other business units to manufacture energy management units

12

as well as special DC link

converters. And an article on the latter reiterates what was said above about the danger of focusing only on

the price: ‘Over the last few years, cost and space considerations have led to an expansion of the thermal

insulation classes up to class H (180ºC)—a development that has brought with it numerous disadvantages…

13

’.

Apart from the fact that—strictly speaking—it should have read ‘…price and space considerations…’ (since

price and cost are not the same), the article underscores the company’s praiseworthy attitude regarding the

question of transformer efficiency.

11

www.riedel-trafobau.de, www.buerkle-schoeck.de

12

Decker, Christiane: ‘Energie sparen mit EMU’ [‘Saving energy with EMUs’], in de, vol. 15-16/2000, p. 34

13

Bürkle, Thomas: ‘Wassergekühlte Zweipunkt-Zwischenkreisdrosseln’ [‘Water-cooled two-point DC link

reactors’], in etz, vol. 22/2000, p. 18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-48-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 47

sheet steel. Although moving from Version 6 to 7 involves only a change in the core material, the copper losses

also decrease due to the higher magnetizability of the grain oriented steel. The stack height of the core in

Version 7 is lower and the average length of a turn is therefore shorter.

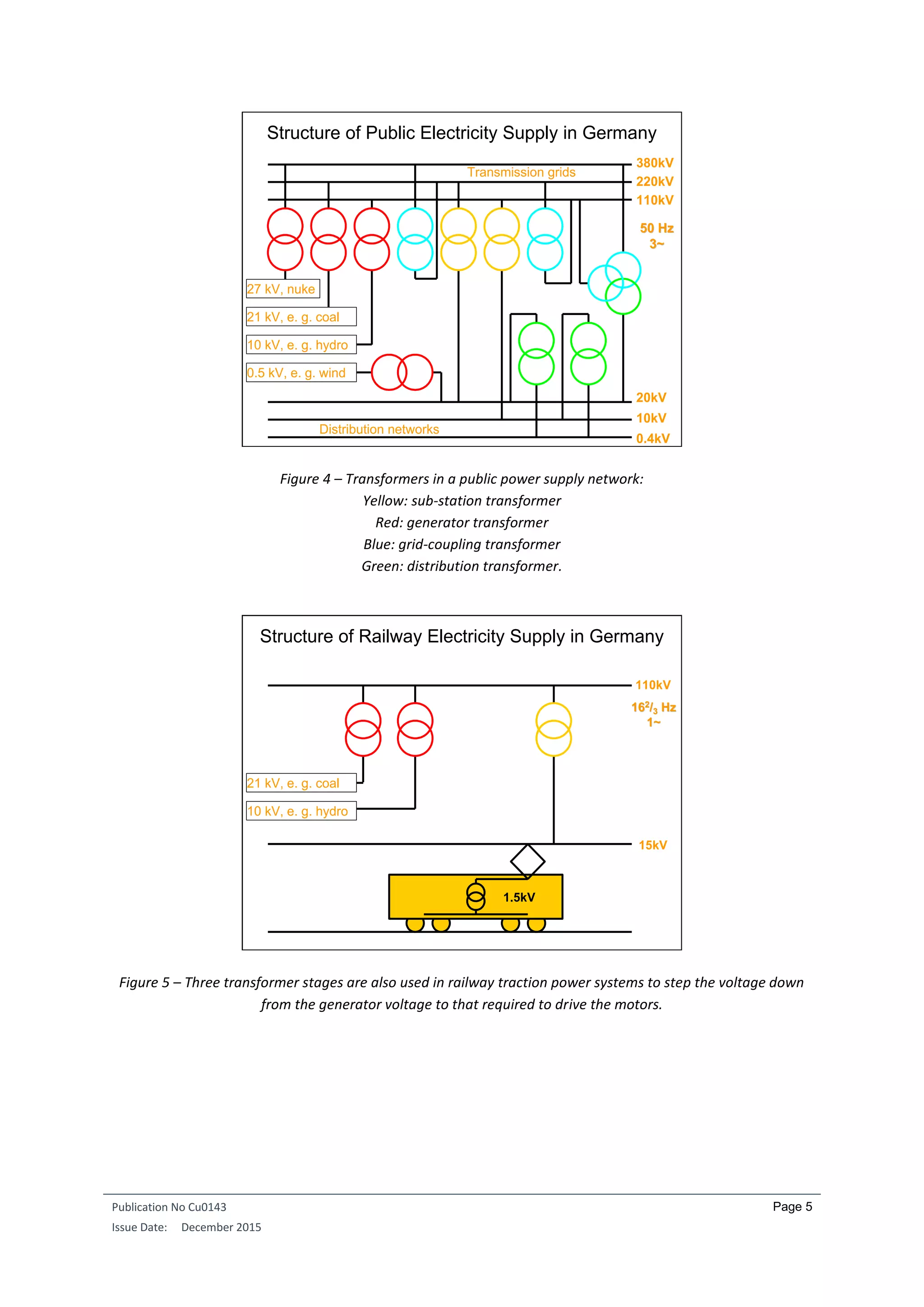

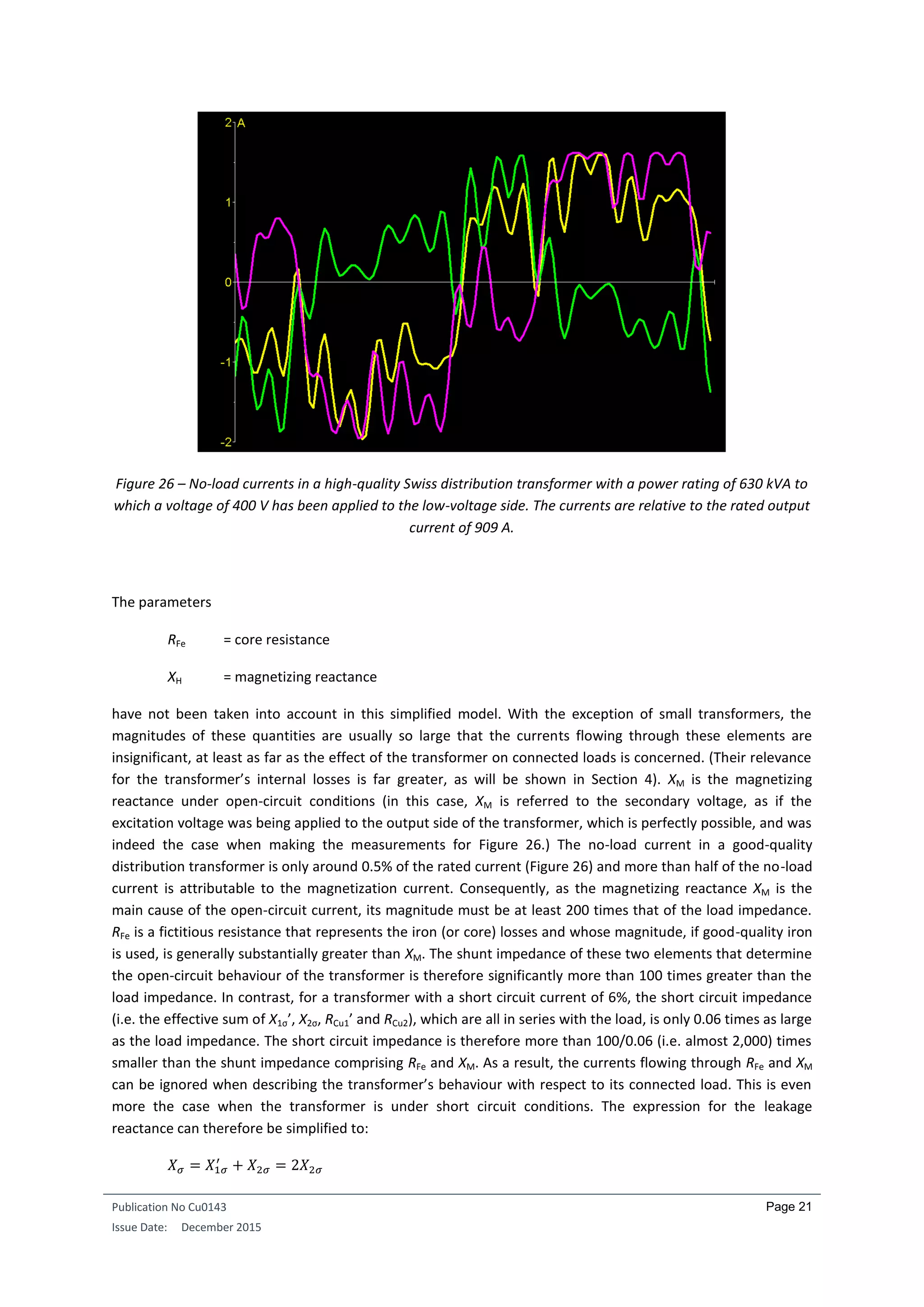

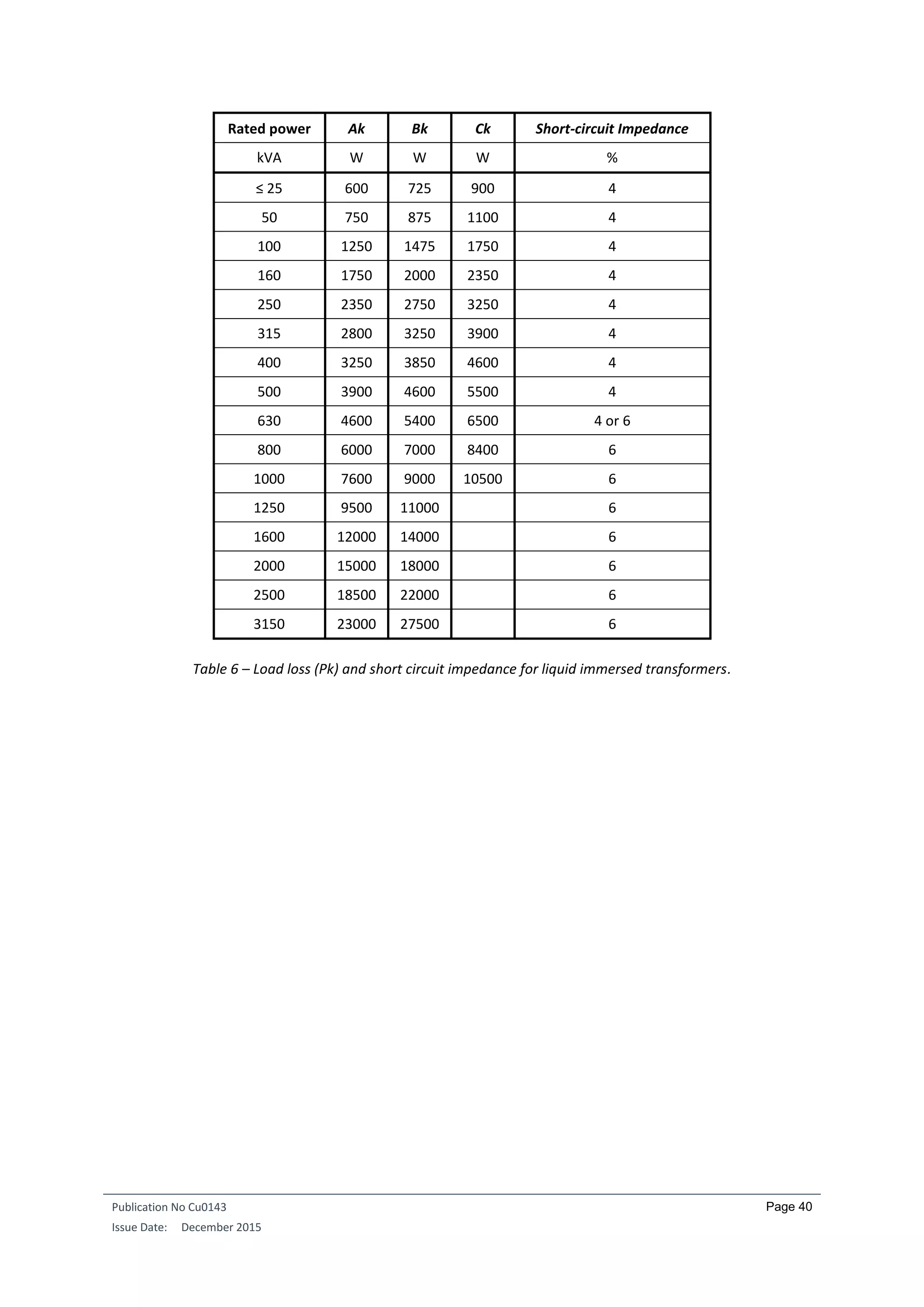

Table 11 – Improving a cheap transformer (Version 0) in seven steps.

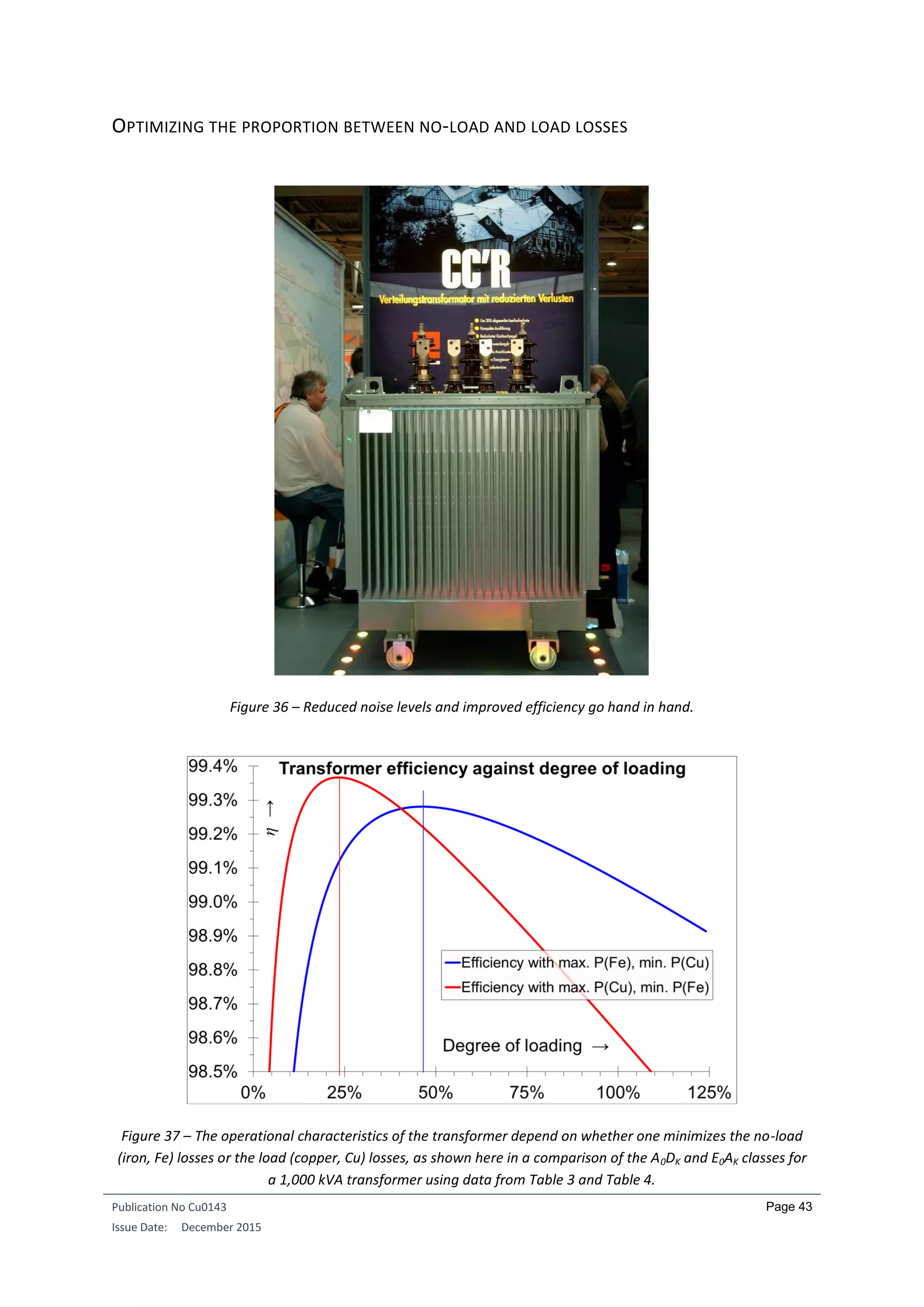

The effects of the stepwise introduction of loss-reducing measures are not immediately apparent in the data in

Table 11 and for this reason have been presented graphically in Figure 40. Two results stand out straight away:

Viewed across the series of improvements, the losses decrease significantly faster than the price rises.

The payback period is nearly always under 1.5 years, only the version with the higher quality sheet

steel core requires longer. The calculations assumed an electricity price of 10 cents per kWh, 242

working days per year, and a single eight-hour shift per day. If there are two shifts a day, the payback

periods are halved.

There is one other beneficial technical side effect from the loss reduction measures: The voltage drop in the

transformer decreases as one moves from Version 0 to 7. This is not always advantageous, especially in

transformers larger than the one considered here where a defined voltage drop is highly desirable. In large

transformers, cooling and electrical insulation requirements mean that it is not possible to eliminate the

cooling ducts. But the example transformer is relatively small, and both the input and output sides are in the

low-voltage range. Furthermore, a small voltage drop (both ohmic and inductive) was advantageous given the

particular industrial process under consideration.

When asked one year later about which of the eight variants the customer finally chose, the manufacturer

became a little embarrassed: ‘I really ought not to say. The customer went for the cheapest product. But not

only that, he also got the loads wrong. So one by one, the transformers are now burning out.’ Any one of the

improved transformer variants 5, 6, or 7 would have had sufficient reserve capacity to cope with the erroneous

load specifications and to prevent transformer failure.

Channels / Design Measures & Weights Calculated Electrical Values Pay-

Ver-

sion

betw. core &

LV winding

in LV winding

betw. LV &

HV winding

in HV winding

stack

height

width length mFe mCu mtot Pv Fe Pv Cu Pvtot U

Price back

time

front

[mm]

long

[mm]

front

[mm]

long

[mm]

front

[mm]

long

[mm]

front

[mm]

long

[mm]

[mm] [mm] [mm] [kg] [kg] [kg] [W] [W] [W] [V] [%] [€] [a]

0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 450 360 202 30.7 232.7 417 1634 2051 13 95.1% 877 ---

1 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 0 100 415 365 196 42.4 238.4 406 1343 1749 11 95.8% 932 0.944

2 10 10 0 0 10 10 10 0 100 417 342 196 46.6 242.6 406 1217 1623 10 96.1% 946 0.839

3 10 10 0 0 10 0 10 0 100 400 342 196 48.2 244.2 406 1090 1496 9 96.4% 955 0.723

4 10 10 0 0 10 10 0 0 100 406 340 196 59.9 255.9 406 874 1280 6 96.9% 1027 1.004

5 10 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 100 408 335 196 65.9 261.9 406 753 1159 5 97.2% 1062 1.072

6 As in 5, but with even thicker wire 100 412 341 196 71.3 267.3 406 626 1032 4 97.5% 1100 1.133

7 As in 5, but with grain-oriented steel, lower stack height 80 412 311 155 64.7 219.7 223 580 803 4 98.0% 1249 1.541](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-50-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 52

In Europe, some believe that the introduction of higher voltage levels would also help to reduce the amount of

electrical energy consumed illegally—referred to euphemistically as non-technical losses’. Transformers as

anti-theft devices? It has even been suggested that the introduction of the lower frequency of 16.7 Hz for the

railway traction power grids used in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and a number of Scandinavian countries

also served the same purpose. The truth, however, is that the lower frequency helps to reduce commutation

problems affecting the ac commutating series motors (universal motors) that power the traction units.

OUTLOOK

While switched-mode power supplies have replaced small transformers in numerous applications, there is

presently no sign that conventional grid transformers will be replaced by any other technology in the near

future. There are suggestions that the extra high voltage level 220 kV will disappear over the long term and

that at some even later date the 380 kV level will be replaced by a DC network

17

. Such developments would

dispense with the need for at least some of the transformers presently required. Regarding energy loss

however, these changes would be essentially neutral, since the inverters and the requisite interference

suppression filters would also generate losses of a similar magnitude.

Attempts have also been made to develop low-loss transformers with superconducting coils

18

. Unfortunately,

these conductors are only really loss-free when conducting direct current. The iron losses can even rise if the

core is also cooled. A further problem is that cooling power has to be supplied continuously at its maximum

required level, thus increasing the no-load losses, despite the fact that in practice, the transformer hardly ever

runs at full load, or if it does, then only for a short time. When all these factors are taken into account, overall

loss reductions turn out to be minimal. The one place where superconducting transformers can be used

effectively is in railway vehicles. Once these transformers go into industrial production they will save not only

weight (and therefore extra energy), but also space. Weight and space limitations in railway vehicles also mean

that the transformers currently in use in railway vehicles are working at their design limits and are thus

significantly less efficient than comparable grid transformers.

17

Fassbinder, Stefan: ‘Hochspannungs-Gleichstrom-Übertragung (HGÜ)’ [‘High-voltage DC power

transmission’], in de, vol. 11/2001, p. gig9, appears in DKI reprint s180 ‘Drehstrom, Gleichstrom, Supraleitung –

Energie-Übertragung heute und morgen’ [‘Three-phase AC, DC and superconducting systems – Power

transmission now and in the future’] from the German Copper Institute (DKI), Düsseldorf.

18

Fassbinder, Stefan: ‘Supraleitung – ein Teil zukünftiger Energieversorgung?’ [‘Superconductivity – What part

will it play in energy supplies of the future?], in de, vol. 9/2001, p. 38, appears in DKI reprint s180 ‘Drehstrom,

Gleichstrom, Supraleitung – Energie-Übertragung heute und morgen’ [‘Three-phase AC, DC and

superconducting systems – Power transmission now and in the future’] from the German Copper Institute

(DKI), Düsseldorf.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-55-2048.jpg)

![Publication No Cu0143

Issue Date: December 2015

Page 55

where n is the harmonic order and In is the associated current expressed as a fraction of the rated current, as

in the numerical example discussed above. But this number is only of use if the terms of reference are known,

i.e. if we know what fraction of the transformer’s losses are made up by the eddy-current losses PSupp.

Normally, though, the only losses (if any) stated on the rating plate are the iron losses P0 and the copper losses

PCu.

In Europe, it is not the K factor, but factor K that is computed, in accordance with harmonization document HD

538.3.S1:

𝐾 = [1 +

𝑒

1 + 𝑒

(

𝐼ℎ

𝐼

)

2

∑ (𝑛 𝑞

(

𝐼 𝑛

𝐼1

)

2

)

𝑛=𝑁

𝑛+2

]

0.5

Where

𝐼 = (∑(𝐼 𝑛)2

𝑛=𝑁

𝑛=1

)

0.5

= 𝐼1 [∑ (

𝐼 𝑛

𝐼1

)

2𝑛=𝑁

𝑛=1

]

0.5

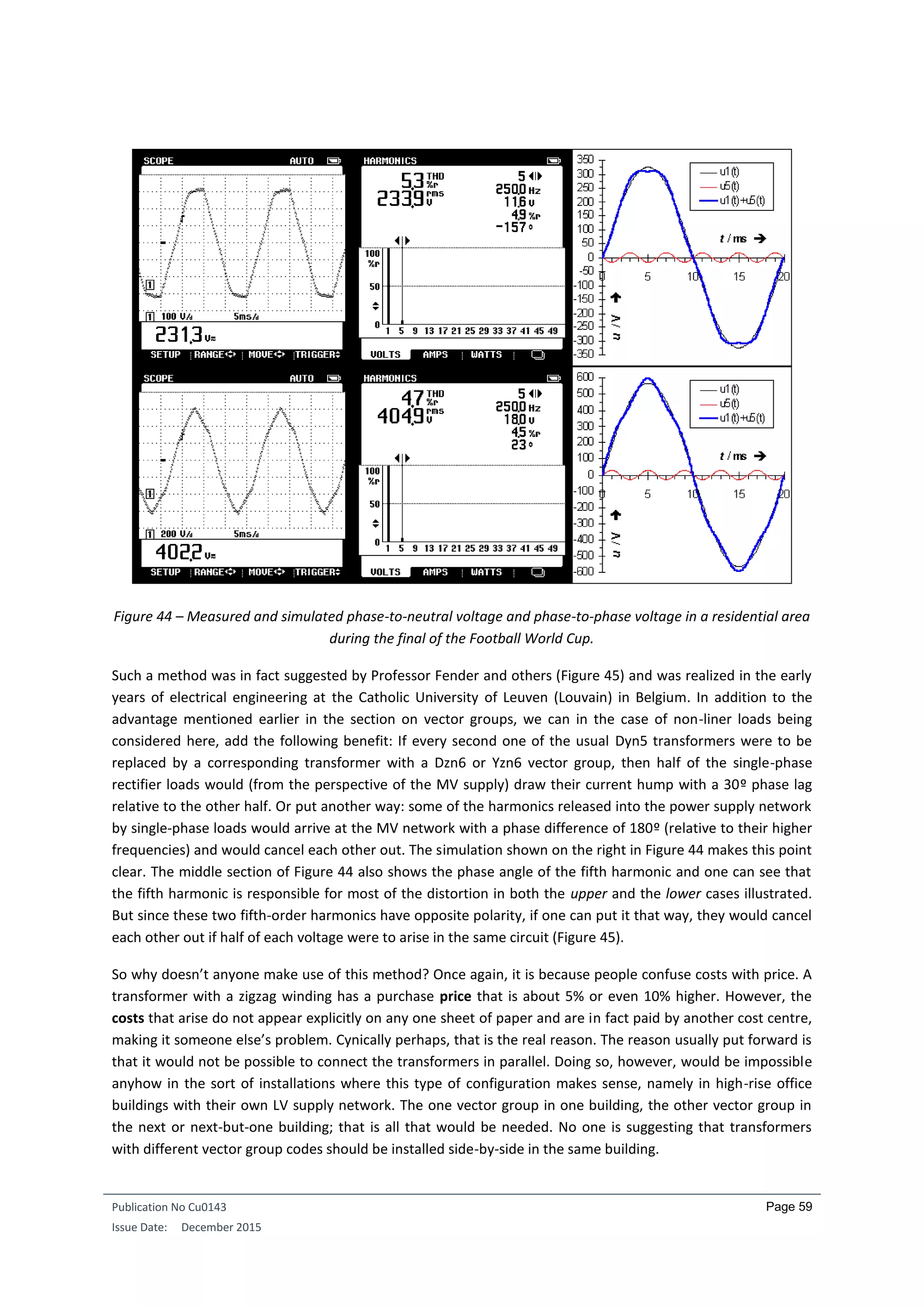

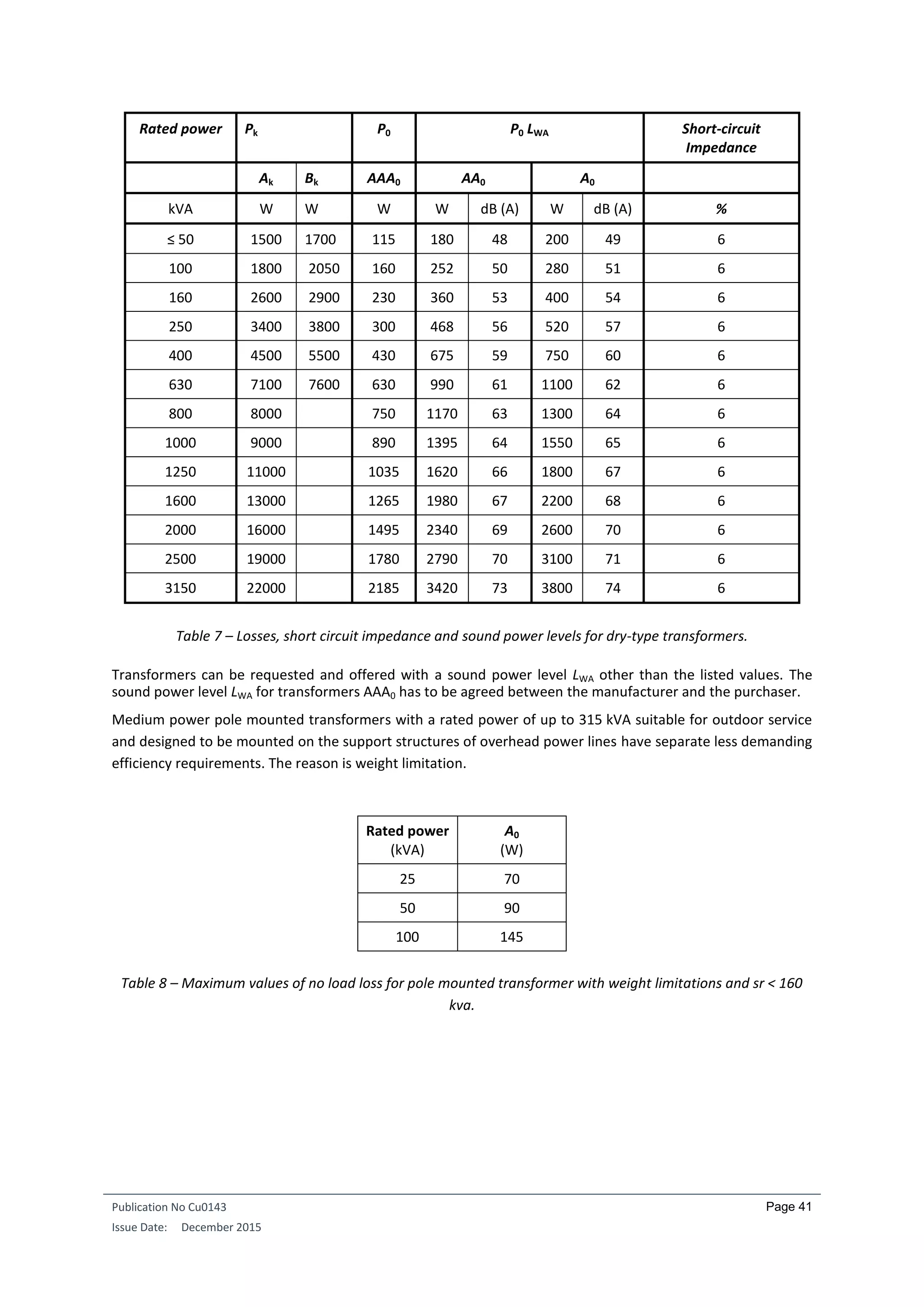

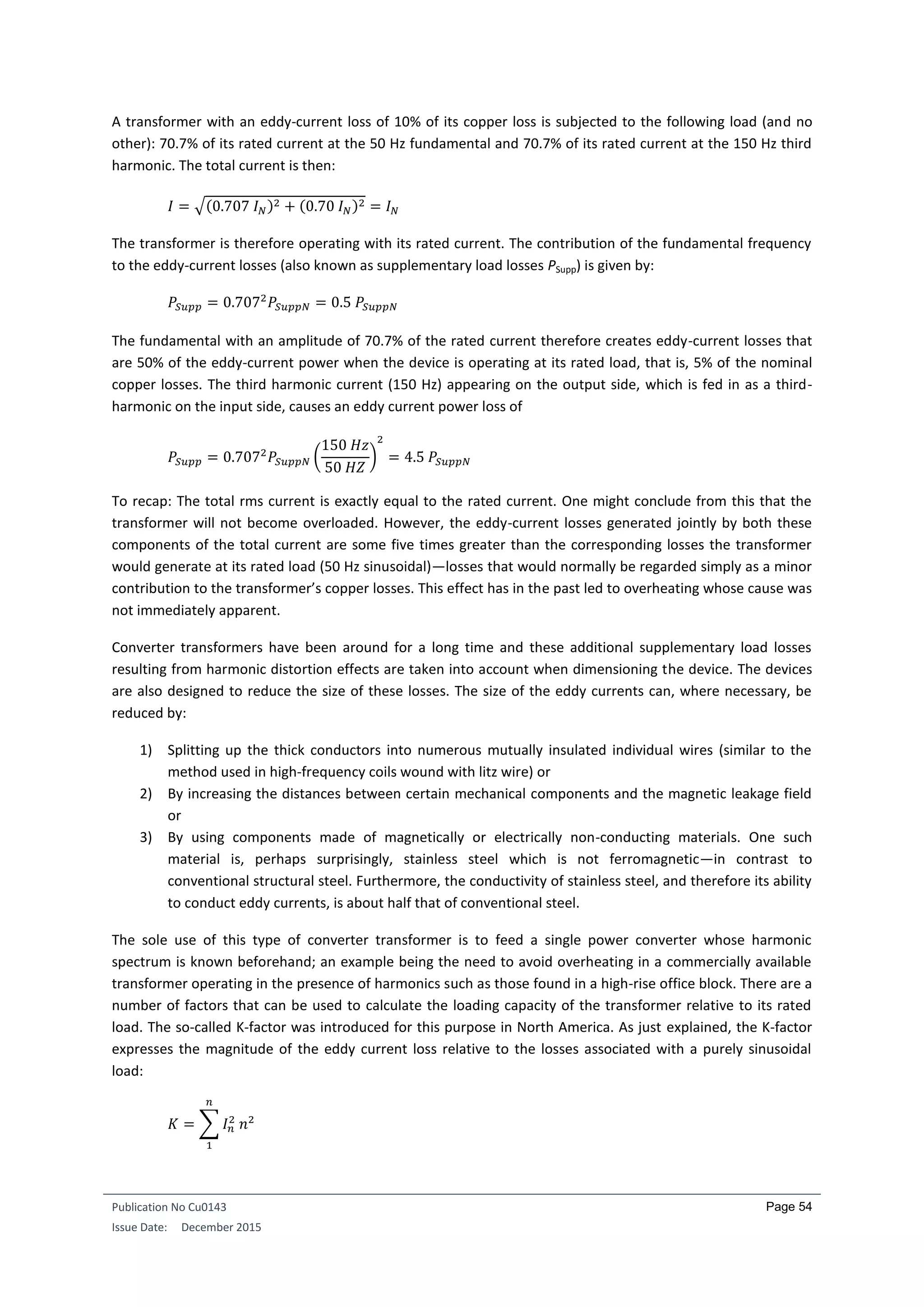

Figure 43 – Current and harmonic spectrum of an 11 watt compact fluorescent lamp (CFL). Top: CFL connected

to a transformer driving an average load in a residential area. Bottom: Simulation of a transformer operating

at its rated current and driving only CFLs.

That is probably enough to frighten most people off. If an electrical engineer or technician working on real

practical problems puts in the hard work and succeeds in correctly applying these exact formulae, he or she is

still left with the question of just what these results are actually saying and how exact they really are. Since the

transformer system being planned does not actually exist, the output values fed into the equations above can

only be based on assumptions, guesswork, or experience. Clearly neither prior measurement on the system

nor prior questioning of the subsequent user is possible. Many buildings today are planned and built and only

then does the owner seek tenants or buyers. Consequently, the harmonic profile of the power supply system is

unknown at the time of planning. We should no doubt adopt a more practical approach to this problem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cu0143-an-distributiontransformersv3-190429221715/75/Transformers-in-Power-Distribution-Networks-58-2048.jpg)