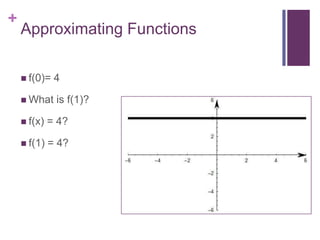

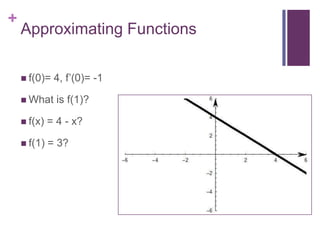

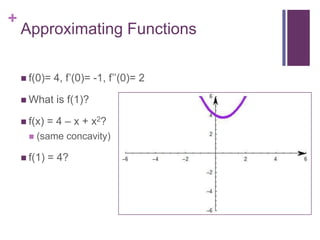

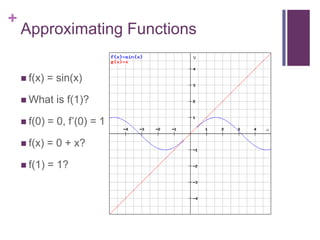

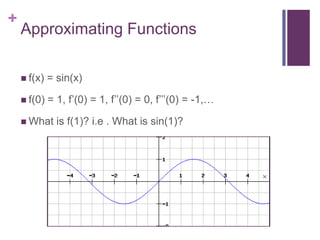

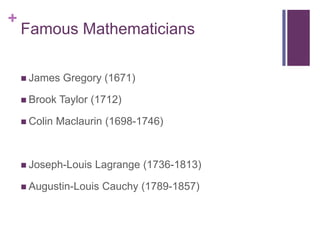

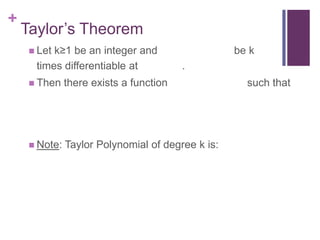

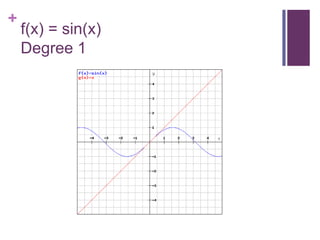

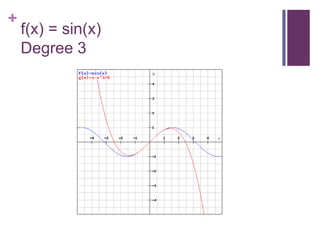

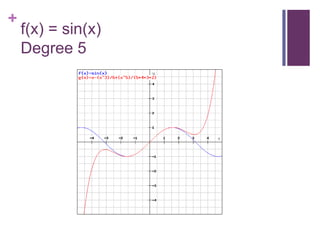

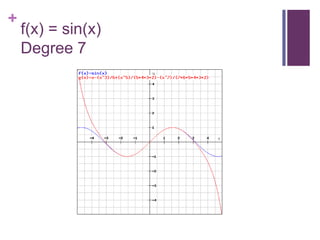

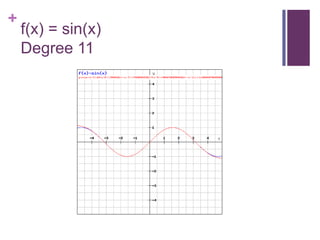

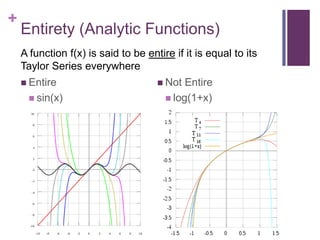

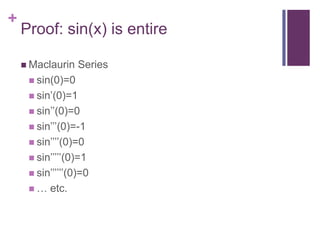

This document discusses Taylor series and their applications. It begins by showing examples of using Taylor series to approximate functions at different points. It then provides background on famous mathematicians who contributed to the development of Taylor series. It explains Taylor's theorem which forms the basis for Taylor series and polynomial approximations. Several proofs are given, including that Taylor series can be used to represent entire functions like sine. Applications of Taylor series discussed include special relativity, optics, physics, and surveying.

![Proof: sin(x) is entireLagrange formula for the remainder:Let be k+1 times differentiable on (a,x) and continuous on [a,x]. Then for some z in (a,x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylorseries-110507142226-phpapp02/85/Taylor-series-22-320.jpg)

![Lagrange RemainderLagrange formula for the remainder:Let be k+1 times differentiable on (a,x) and continuous on [a,x]. Then for some z in (a,x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/taylorseries-110507142226-phpapp02/85/Taylor-series-28-320.jpg)