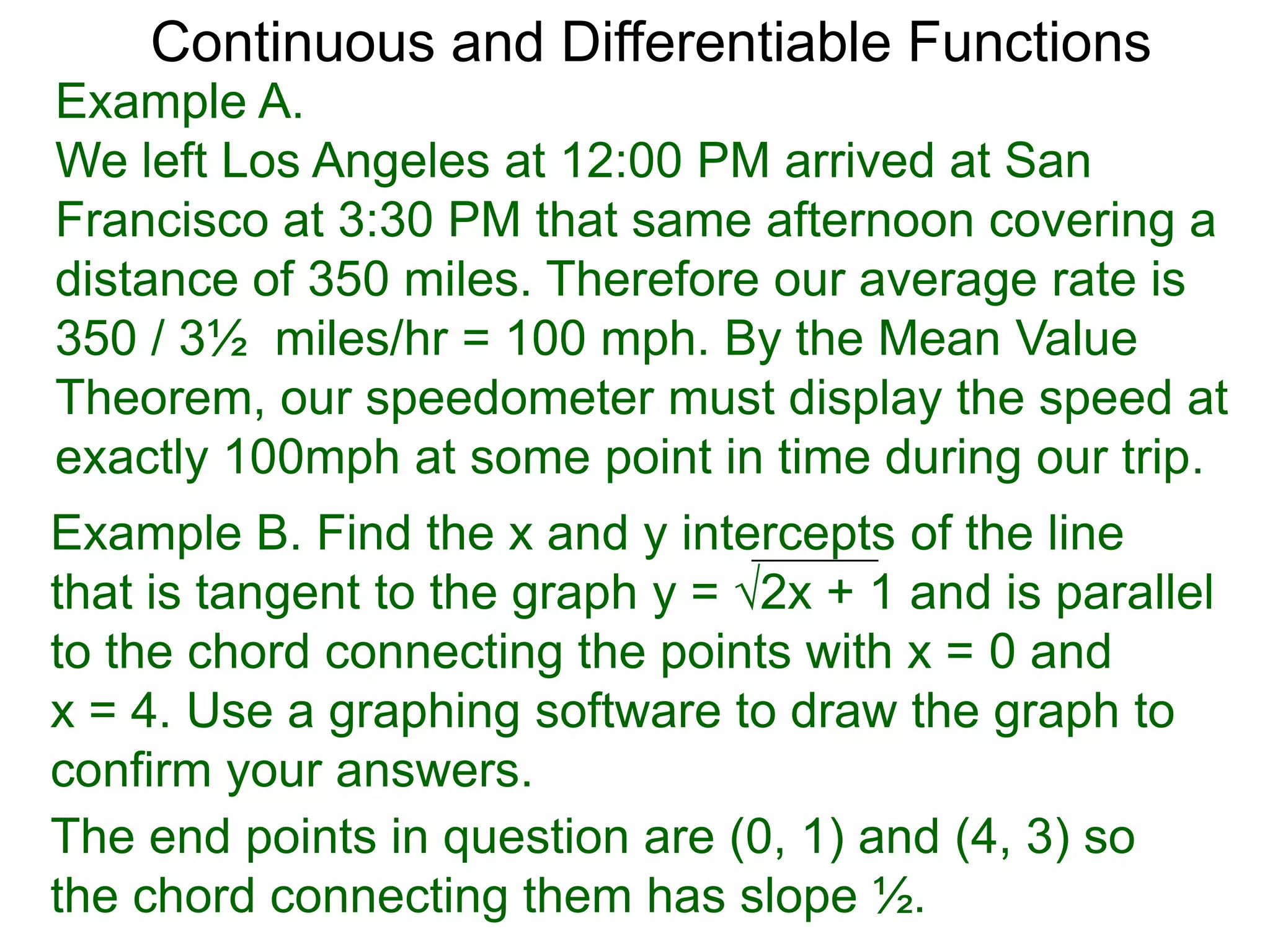

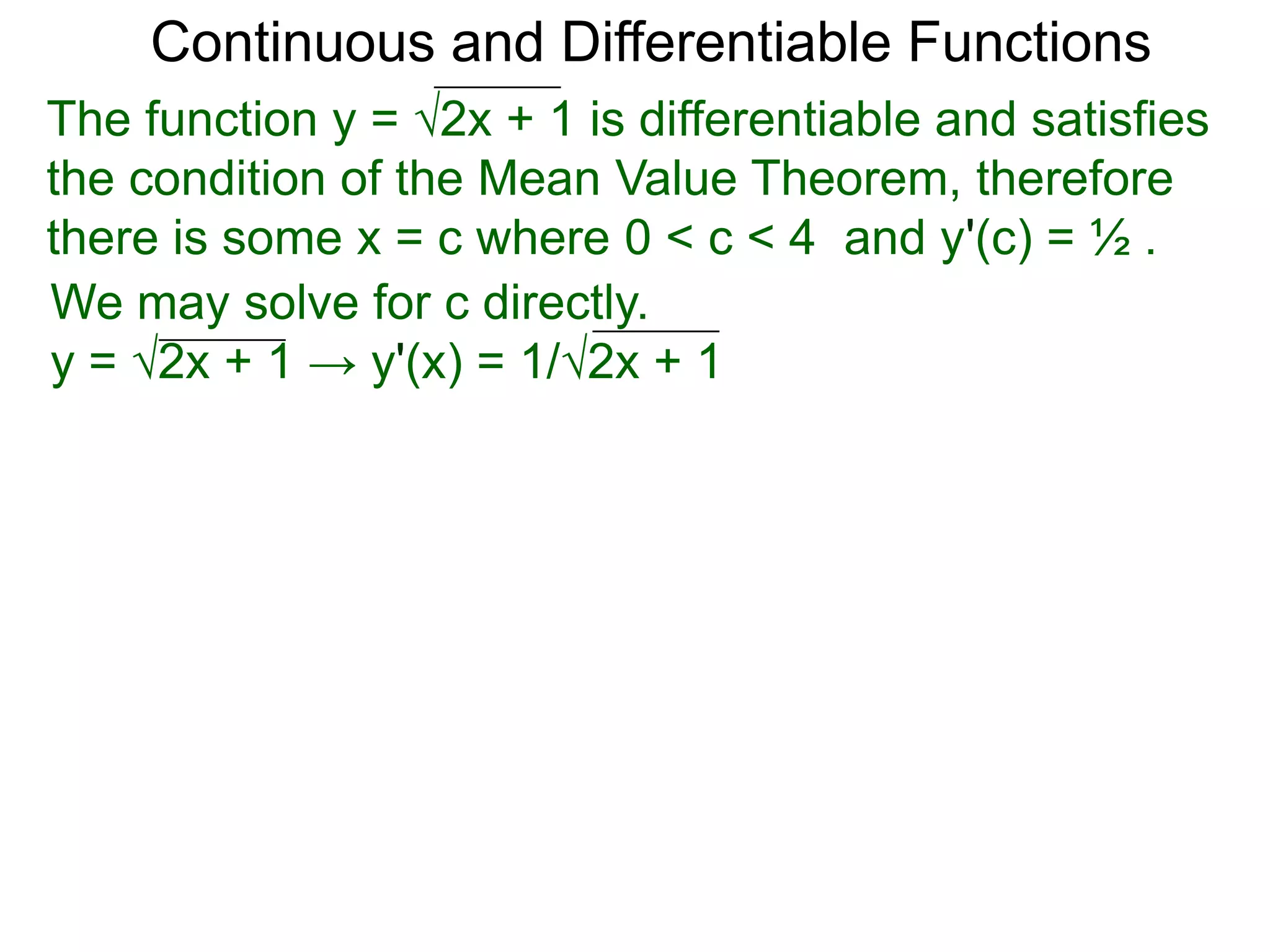

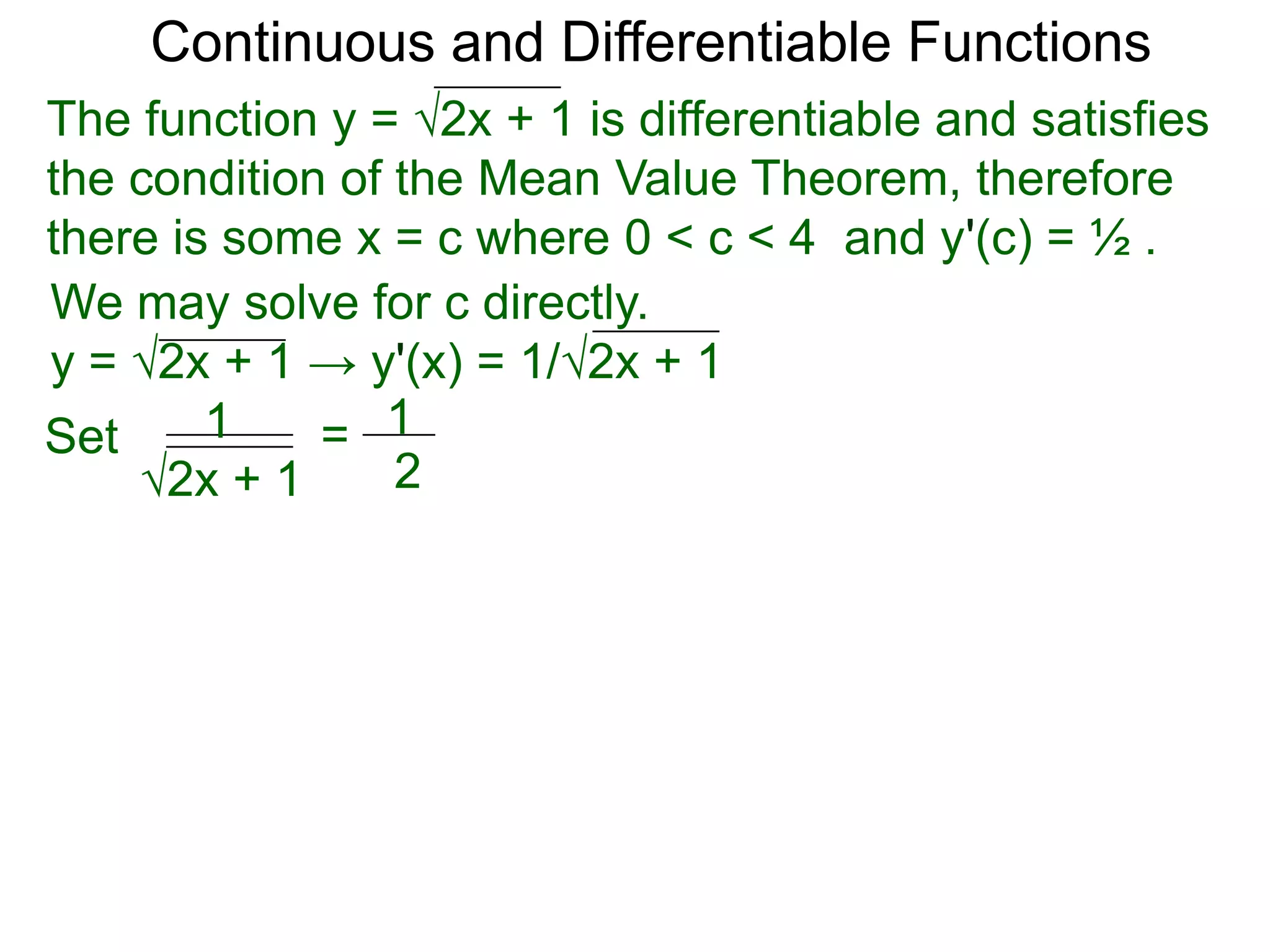

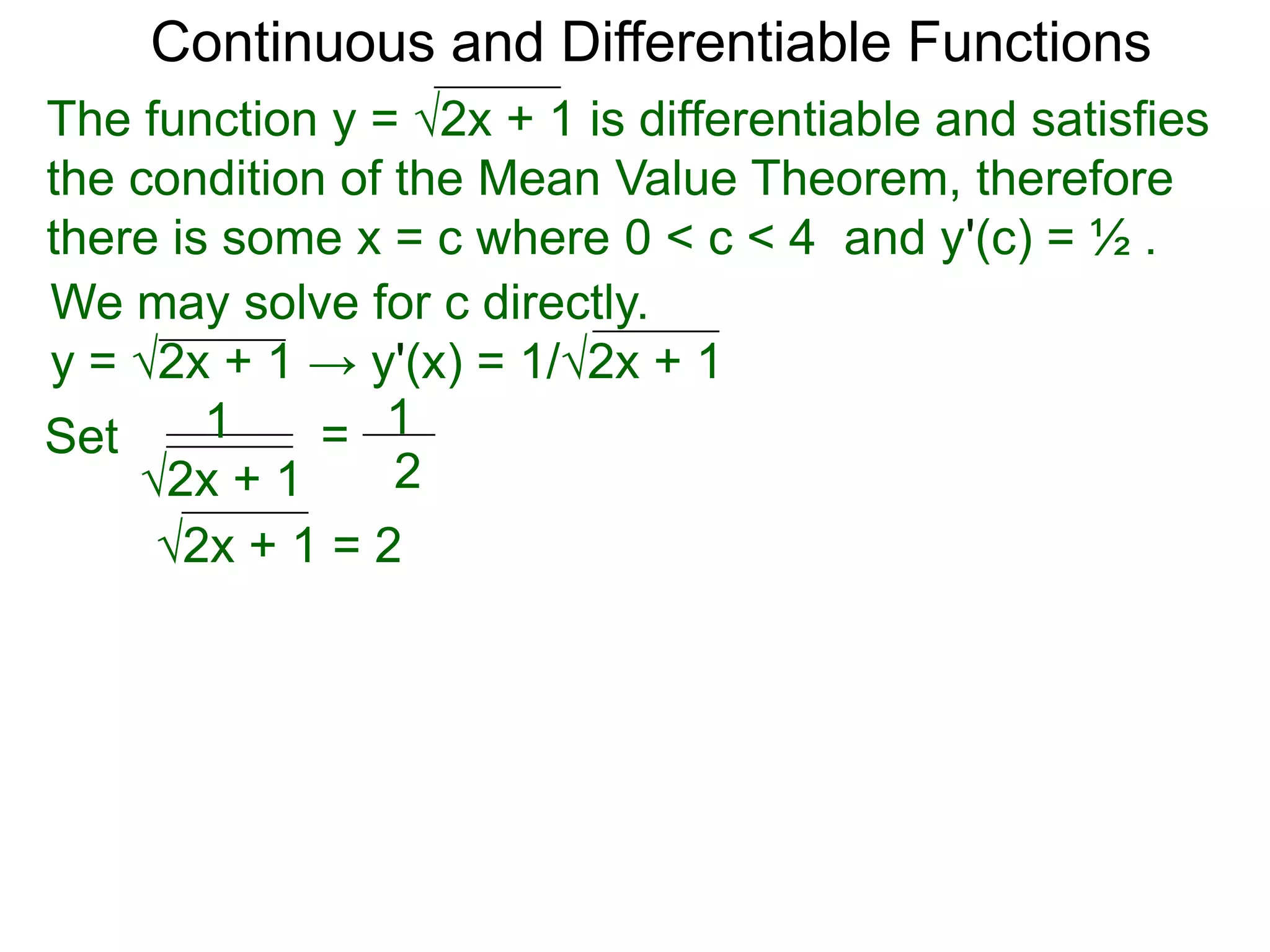

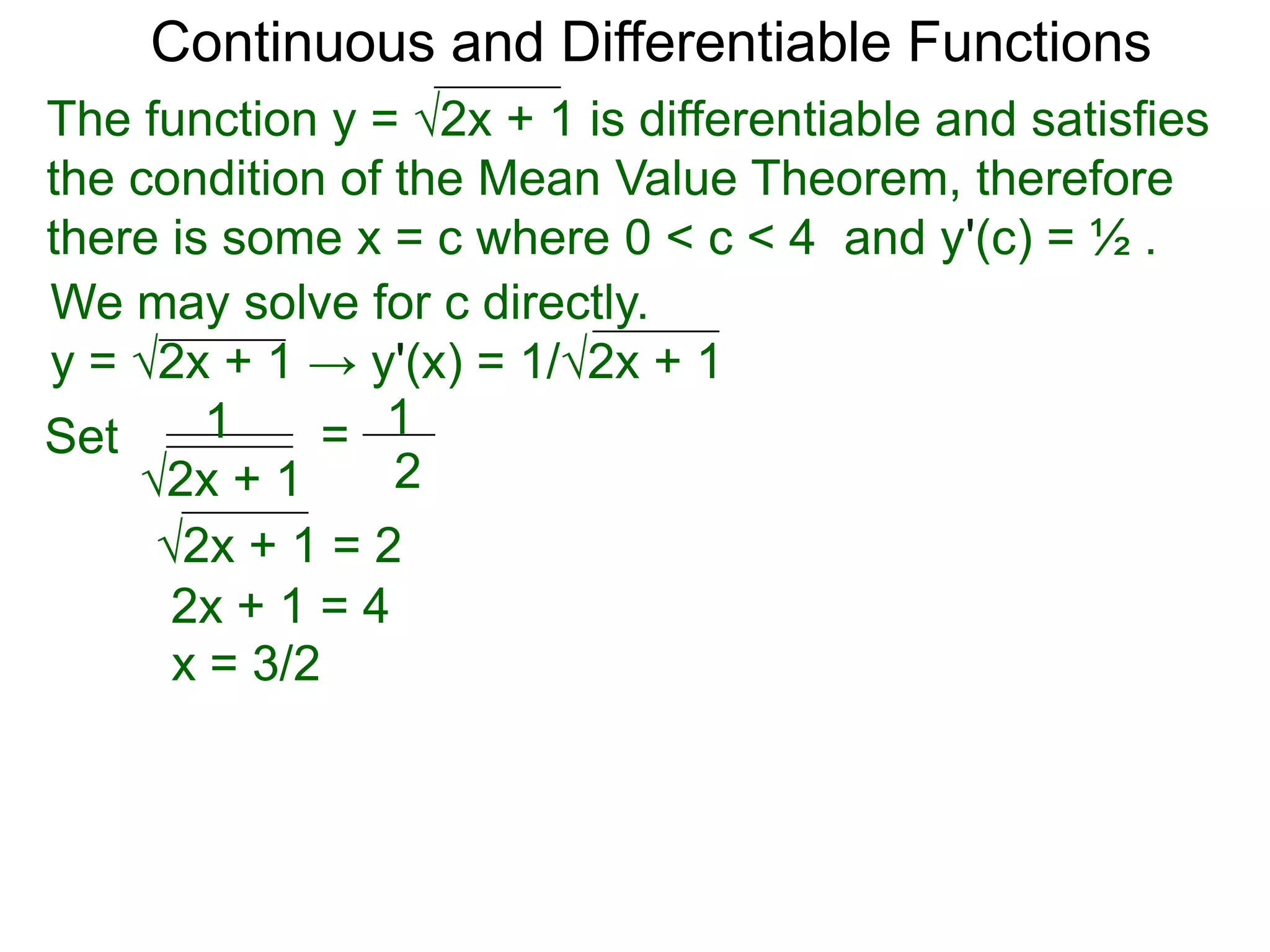

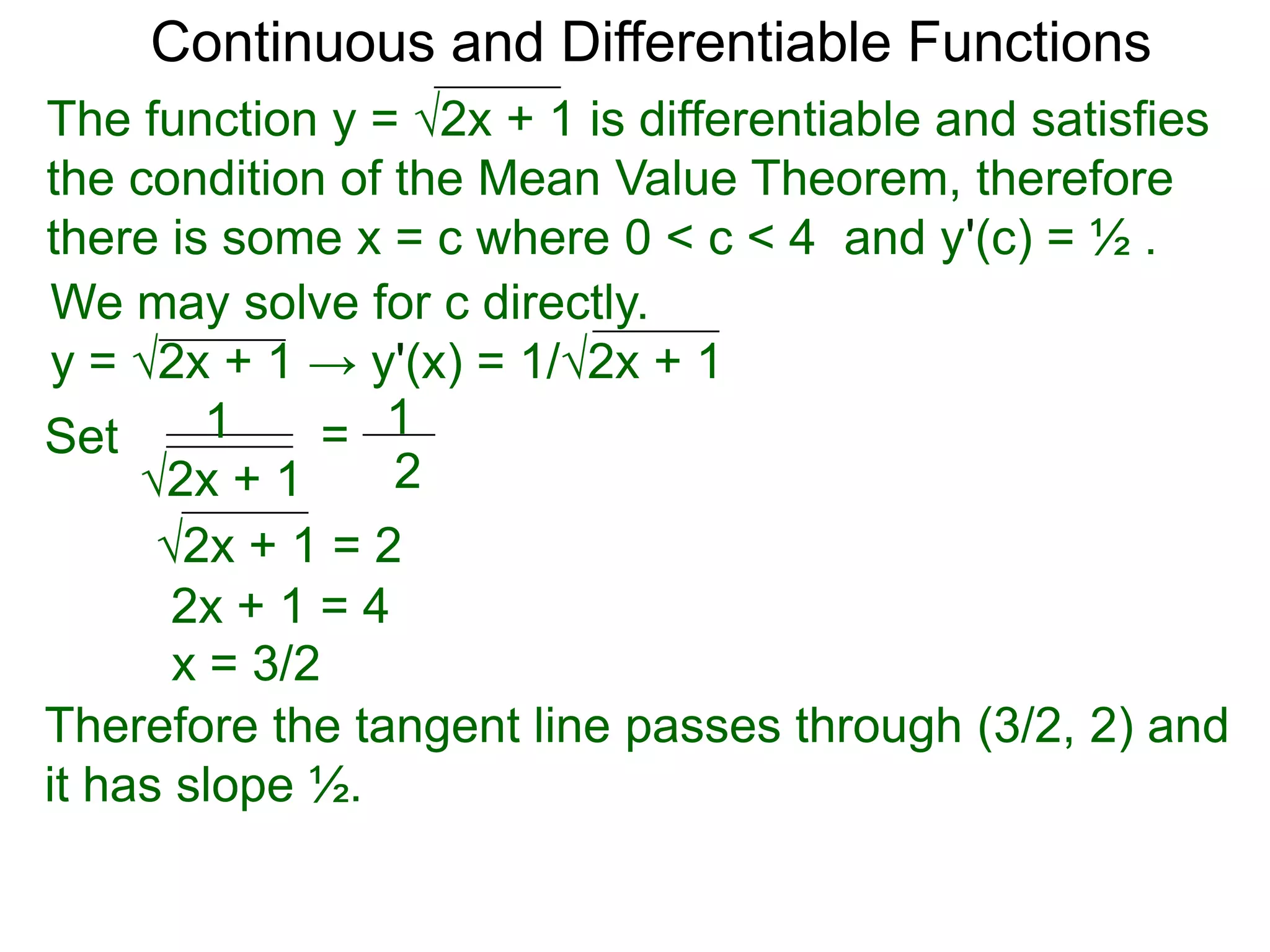

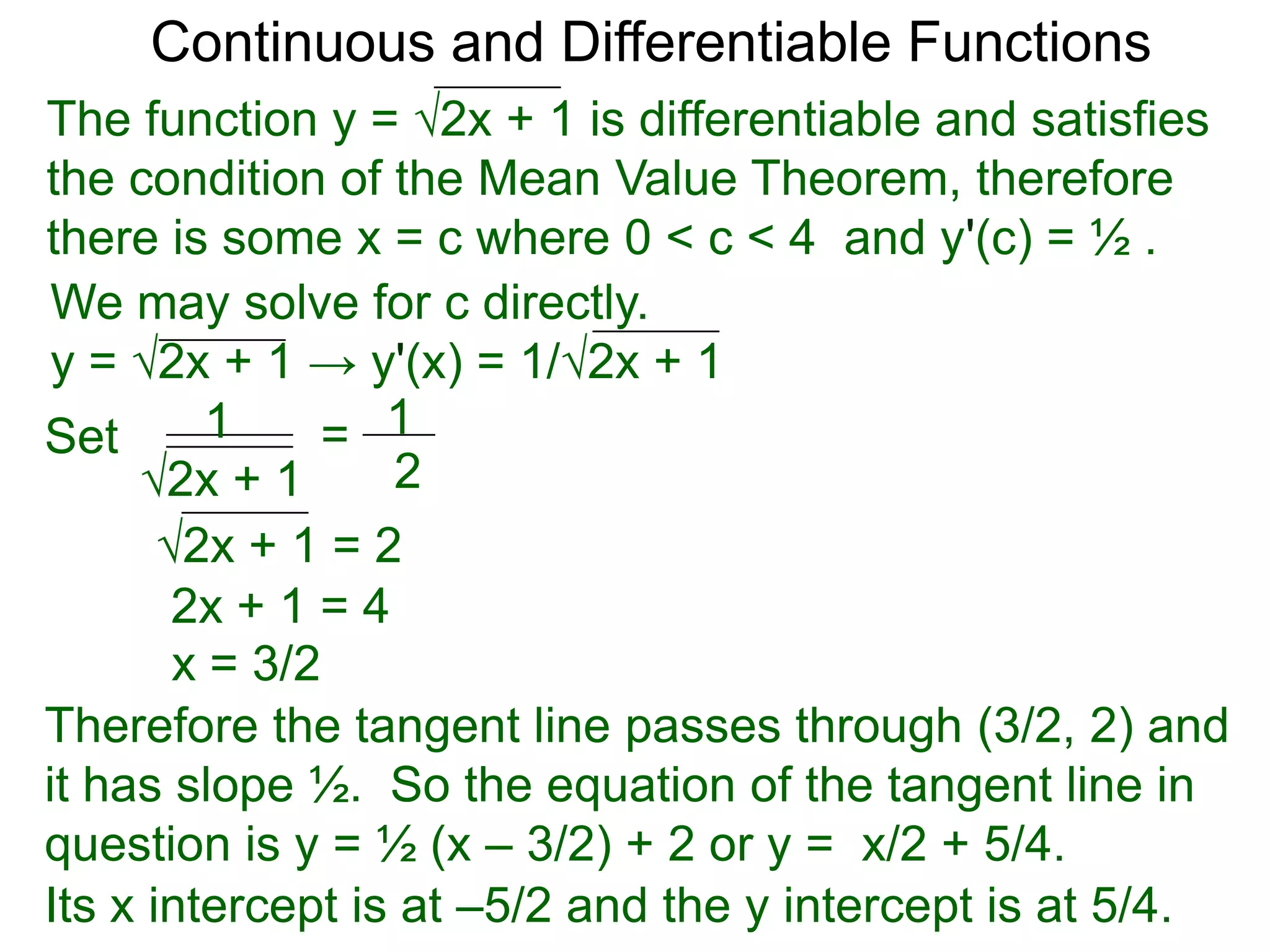

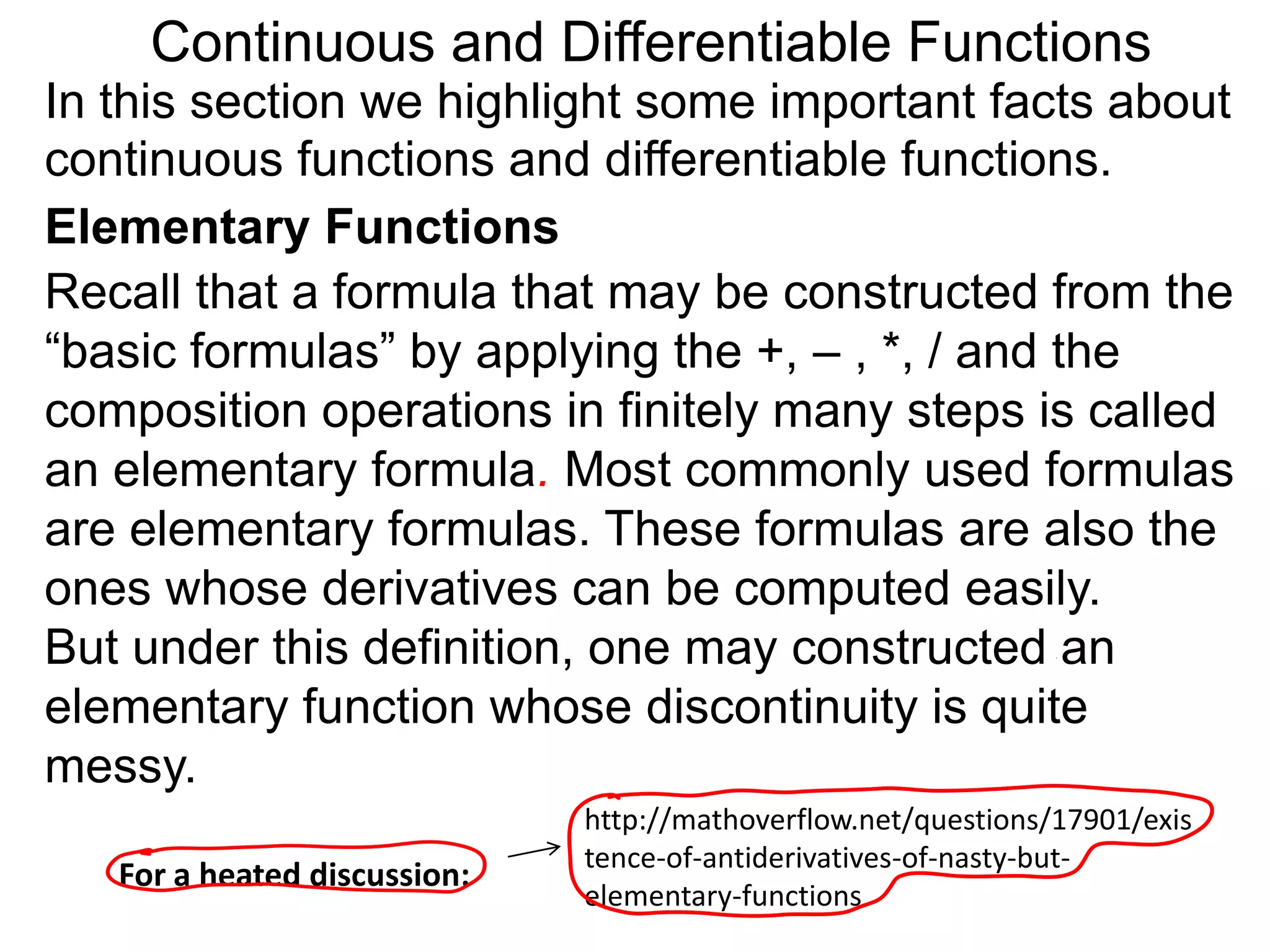

The document discusses continuous and differentiable functions. It defines elementary functions as those constructed using basic operations like addition and multiplication. Continuous functions over a closed interval are bounded and have absolute maximum and minimum values. The Intermediate Value Theorem states that a continuous function takes on all values between its minimum and maximum. Differentiable functions are continuous. Rolle's Theorem says that if a differentiable function is equal at the endpoints of an interval, its derivative is zero somewhere in between.

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-13-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

f(b)

f(a)

a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-14-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

let m be any number where f(a) < m < f(b),

f(b)

m

f(a)

a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-15-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

let m be any number where f(a) < m < f(b),

then there exists at least

one c, i.e. one or more, f(b)

where a < c < b,

m

f(a)

a c b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-16-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

let m be any number where f(a) < m < f(b),

then there exists at least

one c, i.e. one or more, f(b)

where a < c < b,

m

and that f(c) = m.

f(a)

a c b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-17-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

let m be any number where f(a) < m < f(b),

then there exists at least other c’s

one c, i.e. one or more, f(b)

where a < c < b,

m

and that f(c) = m.

f(a)

a c b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-18-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Continuous Functions

There are two important facts about continuous

functions.

I. Intermediate Value Theorem

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] such that f(a) < f(b),

let m be any number where f(a) < m < f(b),

then there exists at least other c’s

one c, i.e. one or more, f(b)

where a < c < b,

m

and that f(c) = m.

We omit the proof here. f(a)

Here is a link to its proof.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intermediate a c b

_value_theorem](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-19-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Remarks

I. Similarly, if f(a) > f(b) then there is some c with

a < c < b such that f(c) = m for f(a) > m > f(b).

II. If the condition is f(a) ≤ m ≤ f(b) then the

conclusion is a ≤ c ≤ b.

One important application for this theorem is the

existence of roots.

(Bozano’s Theorem) Let y = f(x) be a continuous

function over the closed interval [a, b], then there

exists at least one c where a < c < b with f(c) = 0

if the signs of f(a) and f(b) are different.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-23-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Remarks

I. Similarly, if f(a) > f(b) then there is some c with

a < c < b such that f(c) = m for f(a) > m > f(b).

II. If the condition is f(a) ≤ m ≤ f(b) then the

conclusion is a ≤ c ≤ b.

One important application for this theorem is the

existence of roots.

(Bozano’s Theorem) Let y = f(x) be a continuous

function over the closed interval [a, b], then there

exists at least one c where a < c < b with f(c) = 0

if the signs of f(a) and f(b) are different.

With this theorem, we conclude that f(x) = x3 – 3x2 – 5

has a root between 2 < x < 5, as in 3.6 Example B,

because f(2) and f(5) have opposite signs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-24-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The other important fact about continuous functions

is the existence of extrema over a closed interval.

II. Extrema Theorem for Continuous Functions

Let y = f(x) be a continuous function defined over a

closed interval V = [a, b], then both the absolute max.

and the absolute min. exist in V.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-27-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The other important fact about continuous functions

is the existence of extrema over a closed interval.

II. Extrema Theorem for Continuous Functions

Let y = f(x) be a continuous function defined over a

closed interval V = [a, b], then both the absolute max.

and the absolute min. exist in V.

In particular if M is the maximum and m is the minimum,

then m ≤ f(x) ≤ M for every x in the interval [a, b].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-28-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The other important fact about continuous functions

is the existence of extrema over a closed interval.

II. Extrema Theorem for Continuous Functions

Let y = f(x) be a continuous function defined over a

closed interval V = [a, b], then both the absolute max.

and the absolute min. exist in V.

In particular if M is the maximum and m is the minimum,

then m ≤ f(x) ≤ M for every x in the interval [a, b].

So a continuous function defined over a closed

interval V is always bounded.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-29-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The other important fact about continuous functions

is the existence of extrema over a closed interval.

II. Extrema Theorem for Continuous Functions

Let y = f(x) be a continuous function defined over a

closed interval V = [a, b], then both the absolute max.

and the absolute min. exist in V.

In particular if M is the maximum and m is the minimum,

then m ≤ f(x) ≤ M for every x in the interval [a, b].

So a continuous function defined over a closed

interval V is always bounded.

Corollary. Let y = f(x) be an elementary function

defined over a closed interval V = [a, b], then f(x) is

continuous over [a, b], hence both the absolute max.

and the absolute min. exist in V.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-30-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-38-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

f(a)=f(b)

x

a c b x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-39-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

then there is at least one c where a < c < b

such that f'(c) = 0. other c’s

f'(c) = 0

f(a)=f(b)

x

a c b x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-40-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

then there is at least one c where a < c < b

such that f'(c) = 0. other c’s

Proof. Consider the following f'(c) = 0

two cases.

f(a)=f(b)

x

a c b x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-41-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

then there is at least one c where a < c < b

such that f'(c) = 0. other c’s

Proof. Consider the following f'(c) = 0

two cases.

1. The function f(x) is a f(a)=f(b)

constant function, i.e. x

a c b x

f(x) = f(a) = k, then f'(x) = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-42-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

then there is at least one c where a < c < b

such that f'(c) = 0. other c’s

Proof. Consider the following f'(c) = 0

two cases.

1. The function f(x) is a f(a)=f(b)

constant function, i.e. x

a c b x

f(x) = f(a) = k, then f'(x) = 0.

Any number c where a < c < b would satisfy f'(c) = 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-43-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Rolle’s Theorem

Let f(x) be a differentiable function defined over the

closed interval [a, b] with a < b and that f(a) = f(b),

then there is at least one c where a < c < b

such that f'(c) = 0. other c’s

Proof. Consider the following f'(c) = 0

two cases.

1. The function f(x) is a f(a)=f(b)

constant function, i.e. x

a c b x

f(x) = f(a) = k, then f'(x) = 0

Any number c where a < c < b would satisfy f'(c) = 0.

2. If the function f(x) is not a constant function,

then there exists an extremum c between a and b, with

f(c) ≠ f(a) and f(c) ≠ (b) and we must have f'(c) = 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-44-2048.jpg)

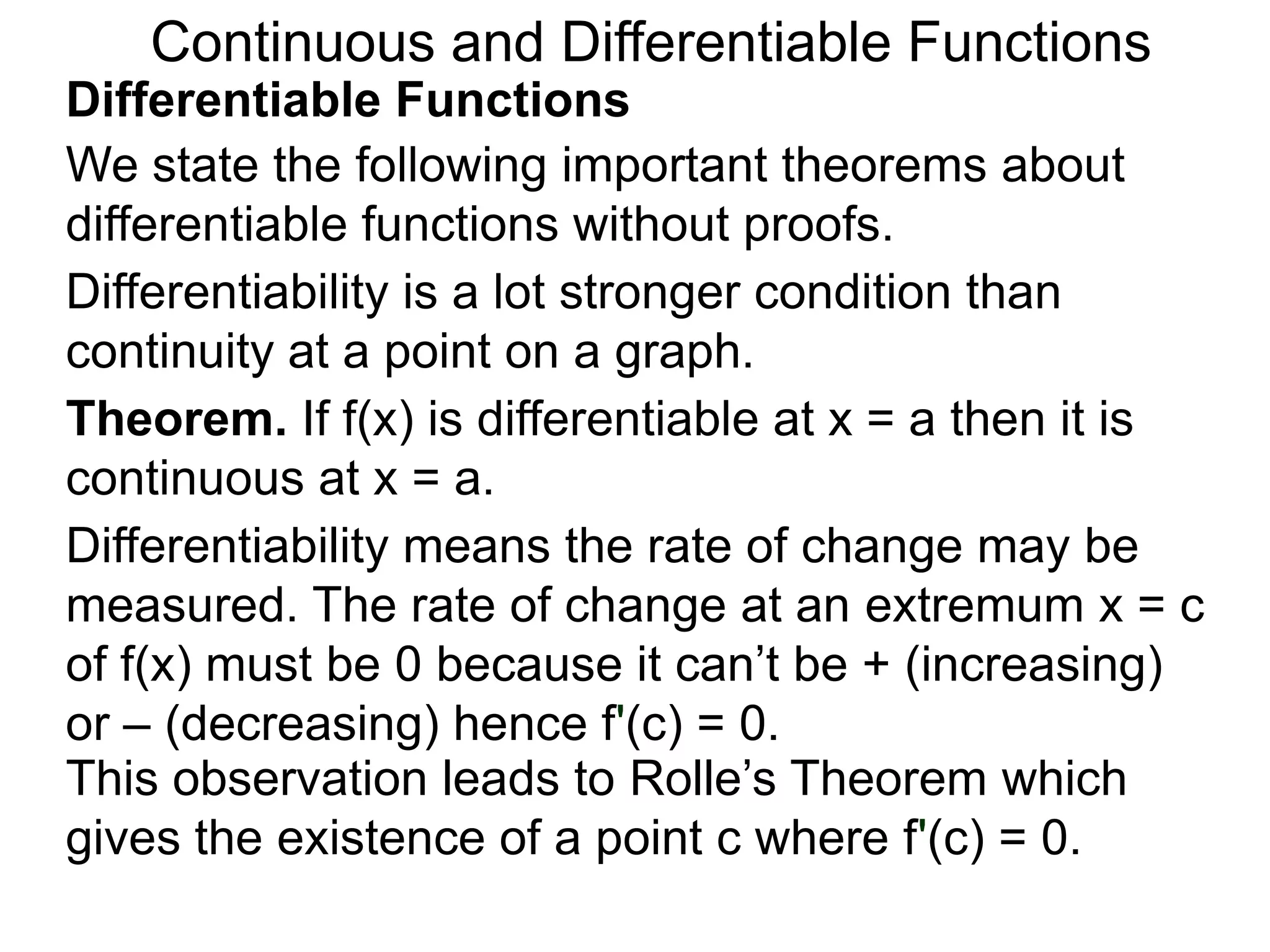

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The average rate of change of y = f(x) from x = a to b

is f(b) – f(a) = Δy = slope of the chord as shown.

Δx

b–a

The graph y = f(x) is the rotation of the graph of some

function y = g(x) defined over some interval [A, B]

Avg. rate of change

y = g(x) y = f(x)

= slope of the chord (b, f(b))

g(A) = g(B) Δy

= Δx

(A, g(A)) (B, g(B)) Δy

Δx

(a, f(a))

Rotate

A C B a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-46-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

The average rate of change of y = f(x) from x = a to b

is f(b) – f(a) = Δy = slope of the chord as shown.

Δx

b–a

The graph y = f(x) is the rotation of the graph of some

function y = g(x) defined over some interval [A, B]

with g(A) = g(B) with the rotation taking

(A,g(A)) to (a, f(a)) and (B,g(B)) to (b, f(b)) as shown.

Avg. rate of change

y = g(x) y = f(x)

= slope of the chord (b, f(b))

g(A) = g(B) Δy

= Δx

(A, g(A)) (B, g(B)) Δy

Δx

(a, f(a))

Rotate

A C B a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-47-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

If in addition y = g(x) is differentiable over an interval

that contains [A, B], then Rolle’s Theorem implies the

existence of at least one C where A < C < B such that

the tangent line at (C, g(C)) is a horizontal.

y = f(x)

Rolle’s Theorem

y = g(x) (b, f(b))

g(A) = g(B)

(A, g(A)) (B, g(B))

(a, f(a))

There exists a C

where g'(C) = 0 Rotate

A C B a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-48-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

If in addition y = g(x) is differentiable over an interval

that contains [A, B], then Rolle’s Theorem implies the

existence of at least one C where A < C < B such that

the tangent line at (C, g(C)) is a horizontal. Under the

rotation this horizontal line rotates into a tangent line

that is parallel to the chord from (a, f(a)) to (b, f(b))

y = f(x)

Rolle’s Theorem

y = g(x) (b, f(b))

g(A) = g(B)

(A, g(A)) (B, g(B))

(a, f(a))

There exists a C There exists a C where

where g'(C) = 0 Rotate f '(C) = Avg. rate of change

A C B a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-49-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

If in addition y = g(x) is differentiable over an interval

that contains [A, B], then Rolle’s Theorem implies the

existence of at least one C where A < C < B such that

the tangent line at (C, g(C)) is a horizontal. Under the

rotation this horizontal line rotates into a tangent line

that is parallel to the chord from (a, f(a)) to (b, f(b))

which gives us the Mean Value Theorem. y = f(x)

Rolle’s Theorem Mean Value Theorem

y = g(x) (b, f(b))

g(A) = g(B)

(A, g(A)) (B, g(B))

(a, f(a))

There exists a C There exists a C where

where g'(C) = 0 Rotate f '(C) = Avg. rate of change

A C B a b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-50-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Mean Value Theorem

Let y = f(x) be a differentiable function over an interval

that contains [a, b], then there is at least one c where

a < c < b such that y = f(x)

f '(c) = f(b) – f(a) . slope = Avg. rate of change (b, f(b))

b–a =

f(b) – f(a)

b–a .

(a, f(a))

a c b

There exists a c where

f(b) – f(a)

f '(c) = Avg. rate of change =

b–a .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-51-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

Mean Value Theorem

Let y = f(x) be a differentiable function over an interval

that contains [a, b], then there is at least one c where

a < c < b such that y = f(x)

f '(c) = f(b) – f(a) . slope = Avg. rate of change (b, f(b))

b–a =

f(b) – f(a)

b–a .

Remarks

1. The precise condition

for the theorem is that (a, f(a))

f(x) is continuous in [a, b],

and differentiable in (a, b).

The condition above is

stronger but is sufficient a c b

for our purposes. There exists a c where

f(b) – f(a)

f '(c) = Avg. rate of change =

b–a .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-52-2048.jpg)

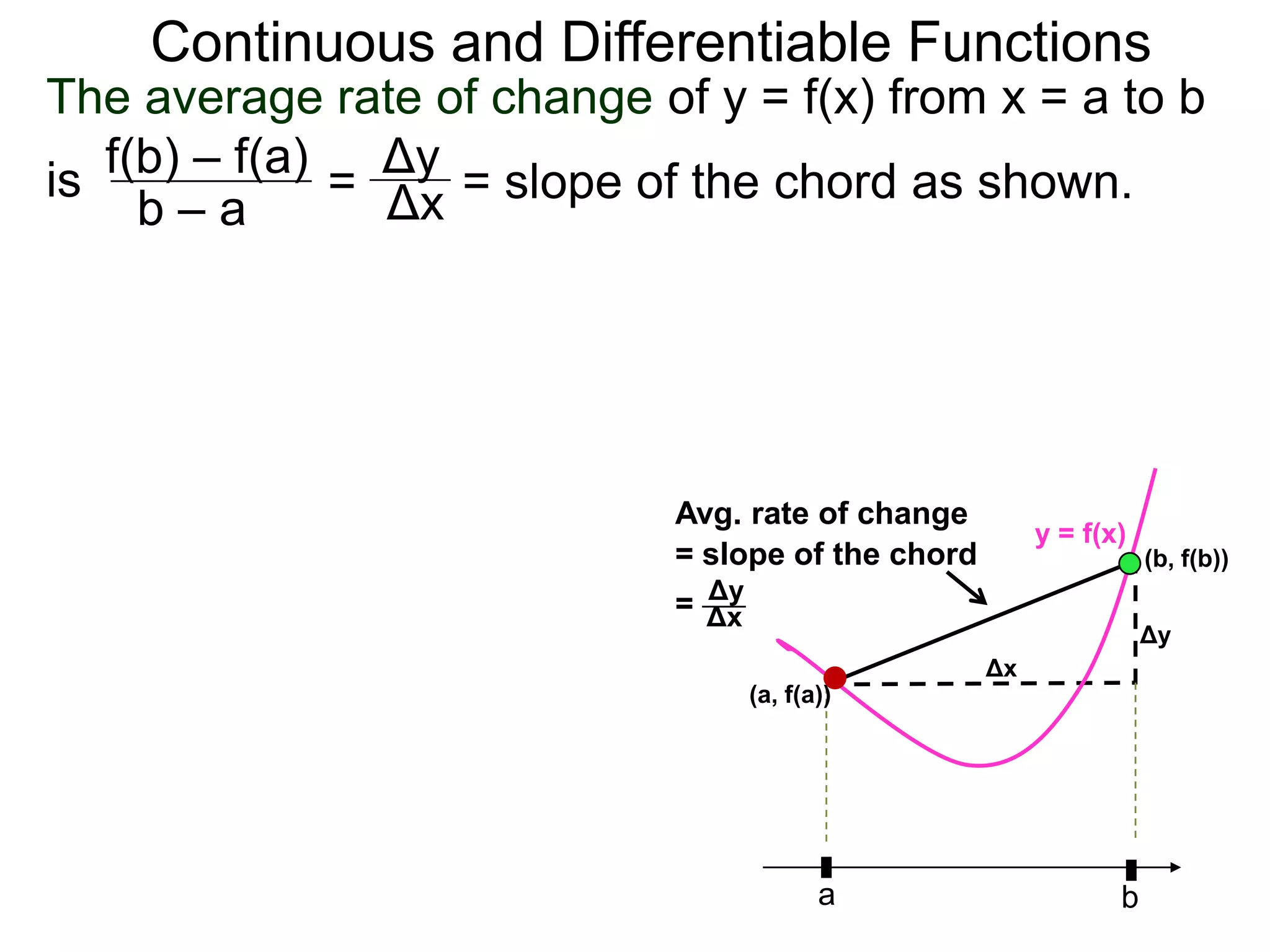

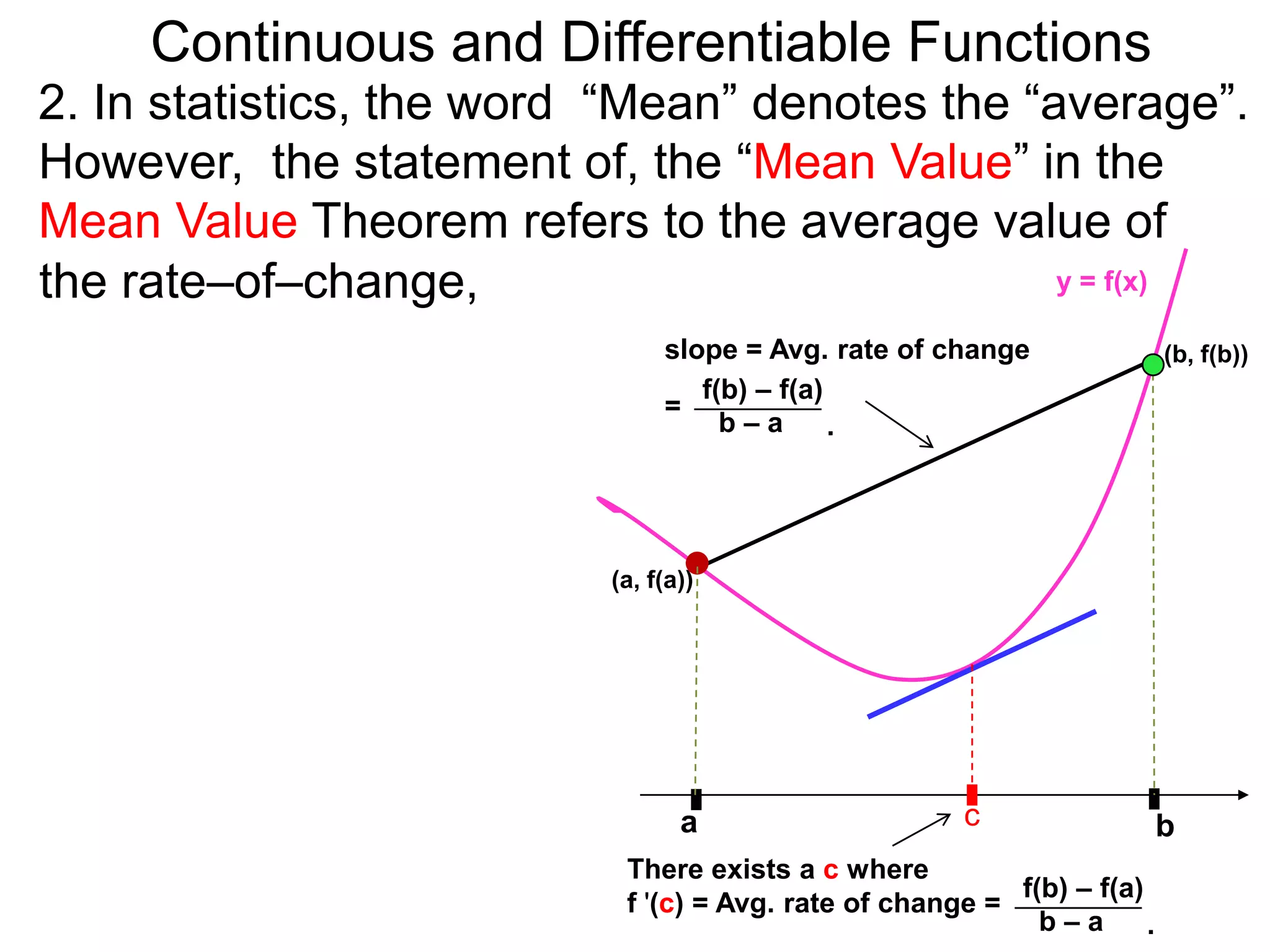

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

2. In statistics, the word “Mean” denotes the “average”.

However, the statement of, the “Mean Value” in the

Mean Value Theorem refers to the average value of

the rate–of–change, y = f(x)

not the “mean value” slope = Avg. rate of change (b, f(b))

f(b) – f(a)

or the average value of =

b–a .

the function f(x) over the

interval [a, b].

(a, f(a))

a c b

There exists a c where

f(b) – f(a)

f '(c) = Avg. rate of change =

b–a .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-54-2048.jpg)

![Continuous and Differentiable Functions

2. In statistics, the word “Mean” denotes the “average”.

However, the statement of, the “Mean Value” in the

Mean Value Theorem refers to the average value of

the rate–of–change, y = f(x)

not the “mean value” slope = Avg. rate of change (b, f(b))

f(b) – f(a)

or the average value of =

b–a .

the function f(x) over the

interval [a, b].

The average value of (a, f(a))

the function f(x) over the

interval [a, b] is defined

by integrals which are

c

our next topics. a b

There exists a c where

f(b) – f(a)

f '(c) = Avg. rate of change =

b–a .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-5continuousfunctionsanddifferentiablefunctions-120508095708-phpapp01/75/4-5-continuous-functions-and-differentiable-functions-55-2048.jpg)