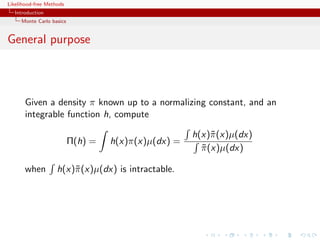

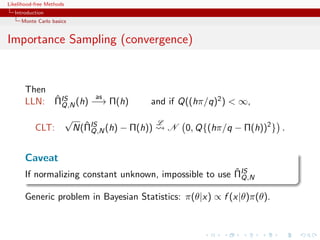

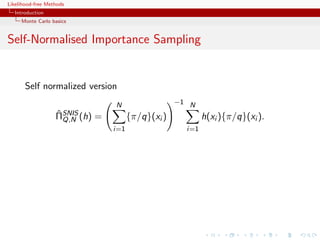

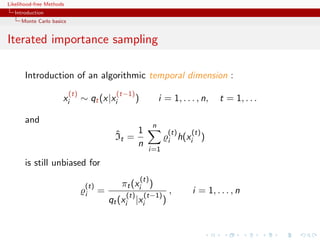

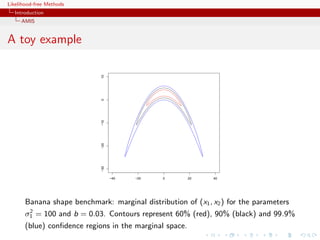

Likelihood-free methods provide techniques for approximating Bayesian computations when the likelihood function is unavailable or computationally intractable. Monte Carlo methods like importance sampling and iterated importance sampling generate samples from an approximating distribution to estimate integrals. Population Monte Carlo is an iterative Monte Carlo algorithm that propagates a population of particles over time to explore the target distribution. Approximate Bayesian computation uses simulation-based methods to approximate posterior distributions when the likelihood is unavailable.

![Likelihood-free Methods

Introduction

Monte Carlo basics

Monte Carlo basics

Generate an iid sample x1 , . . . , xN from π and estimate Π(h) by

N

ΠMC (h) = N −1

ˆ

N h(xi ).

i=1

ˆ as

LLN: ΠMC (h) −→ Π(h)

N

If Π(h2 ) = h2 (x)π(x)µ(dx) < ∞,

√ L

CLT: ˆ

N ΠMC (h) − Π(h)

N N 0, Π [h − Π(h)]2 .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-5-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Introduction

Monte Carlo basics

Monte Carlo basics

Generate an iid sample x1 , . . . , xN from π and estimate Π(h) by

N

ΠMC (h) = N −1

ˆ

N h(xi ).

i=1

ˆ as

LLN: ΠMC (h) −→ Π(h)

N

If Π(h2 ) = h2 (x)π(x)µ(dx) < ∞,

√ L

CLT: ˆ

N ΠMC (h) − Π(h)

N N 0, Π [h − Π(h)]2 .

Caveat

Often impossible or inefficient to simulate directly from Π](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-6-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Introduction

Population Monte Carlo

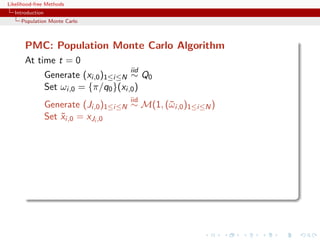

PMC: Population Monte Carlo Algorithm

At time t = 0

iid

Generate (xi,0 )1≤i≤N ∼ Q0

Set ωi,0 = {π/q0 }(xi,0 )

iid

Generate (Ji,0 )1≤i≤N ∼ M(1, (¯ i,0 )1≤i≤N )

ω

Set xi,0 = xJi ,0

˜

At time t (t = 1, . . . , T ),

ind

Generate xi,t ∼ Qi,t (˜i,t−1 , ·)

x

Set ωi,t = {π(xi,t )/qi,t (˜i,t−1 , xi,t )}

x

iid

Generate (Ji,t )1≤i≤N ∼ M(1, (¯ i,t )1≤i≤N )

ω

Set xi,t = xJi,t ,t .

˜

[Capp´, Douc, Guillin, Marin, & CPR, 2009, Stat.& Comput.]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-16-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Introduction

Population Monte Carlo

Improving quality

The efficiency of the SNIS approximation depends on the choice of

Q, ranging from optimal

q(x) ∝ |h(x) − Π(h)|π(x)

to useless

ˆ

var ΠSNIS (h) = +∞

Q,N

Example (PMC=adaptive importance sampling)

Population Monte Carlo is producing a sequence of proposals Qt

aiming at improving efficiency

ˆ ˆ

Kull(π, qt ) ≤ Kull(π, qt−1 ) or var ΠSNIS (h) ≤ var ΠSNIS ,∞ (h)

Qt ,∞ Qt−1

[Capp´, Douc, Guillin, Marin, Robert, 04, 07a, 07b, 08]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-20-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Introduction

AMIS

Mixture representation

Deterministic mixture correction of the weights proposed by Owen

and Zhou (JASA, 2000)

The corresponding estimator is still unbiased [if not

self-normalised]

All particles are on the same weighting scale rather than their

own

Large variance proposals Qt do not take over

Variance reduction thanks to weight stabilization & recycling

[K.o.] removes the randomness in the component choice

[=Rao-Blackwellisation]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-23-320.jpg)

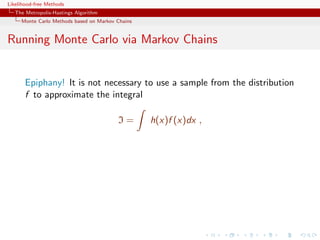

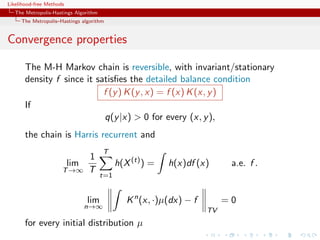

![Likelihood-free Methods

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

Monte Carlo Methods based on Markov Chains

Running Monte Carlo via Markov Chains

Epiphany! It is not necessary to use a sample from the distribution

f to approximate the integral

I= h(x)f (x)dx ,

Principle: Obtain X1 , . . . , Xn ∼ f (approx) without directly

simulating from f , using an ergodic Markov chain with stationary

distribution f

[Metropolis et al., 1953]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-30-320.jpg)

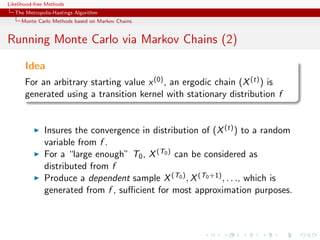

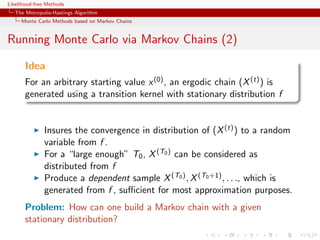

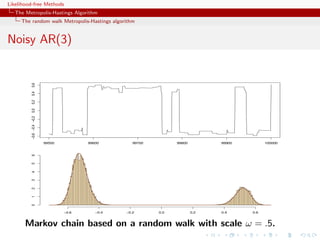

![Likelihood-free Methods

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The random walk Metropolis-Hastings algorithm

Acceptance rate

A high acceptance rate is not indication of efficiency since the

random walk may be moving “too slowly” on the target surface

If average acceptance rate low, the proposed values f (yt ) tend to

be small wrt f (x (t) ), i.e. the random walk [not the algorithm!]

moves quickly on the target surface often reaching its boundaries](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-44-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The random walk Metropolis-Hastings algorithm

Rule of thumb

In small dimensions, aim at an average acceptance rate of 50%. In

large dimensions, at an average acceptance rate of 25%.

[Gelman,Gilks and Roberts, 1995]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-45-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

Meanwhile, in a Gaulish village...

Similar exploration of simulation-based techniques in Econometrics

Simulated method of moments

Method of simulated moments

Simulated pseudo-maximum-likelihood

Indirect inference

[Gouri´roux & Monfort, 1996]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-49-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

Method of simulated moments

Given a statistic vector K (y ) with

Eθ [K (Yt )|y1:(t−1) ] = k(y1:(t−1) ; θ)

find an unbiased estimator of k(y1:(t−1) ; θ),

˜

k( t , y1:(t−1) ; θ)

Estimate θ by

n S

arg min K (yt ) − ˜ t

k( s , y1:(t−1) ; θ)/S

θ

t=1 s=1

[Pakes & Pollard, 1989]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-52-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

Indirect inference

ˆ

Minimise (in θ) the distance between estimators β based on

pseudo-models for genuine observations and for observations

simulated under the true model and the parameter θ.

[Gouri´roux, Monfort, & Renault, 1993;

e

Smith, 1993; Gallant & Tauchen, 1996]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-53-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

Consistent indirect inference

...in order to get a unique solution the dimension of

the auxiliary parameter β must be larger than or equal to

the dimension of the initial parameter θ. If the problem is

just identified the different methods become easier...

Consistency depending on the criterion and on the asymptotic

identifiability of θ

[Gouri´roux, Monfort, 1996, p. 66]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-57-320.jpg)

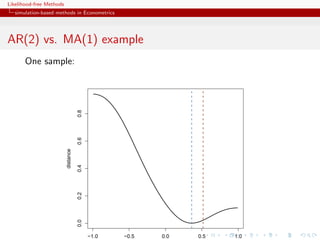

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

AR(2) vs. MA(1) example

true (AR) model

yt = t −θ t−1

and [wrong!] auxiliary (MA) model

yt = β1 yt−1 + β2 yt−2 + ut

R code

x=eps=rnorm(250)

x[2:250]=x[2:250]-0.5*x[1:249]

simeps=rnorm(250)

propeta=seq(-.99,.99,le=199)

dist=rep(0,199)

bethat=as.vector(arima(x,c(2,0,0),incl=FALSE)$coef)

for (t in 1:199)

dist[t]=sum((as.vector(arima(c(simeps[1],simeps[2:250]-propeta[t]*

simeps[1:249]),c(2,0,0),incl=FALSE)$coef)-bethat)^2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-58-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

Choice of pseudo-model

Pick model such that

ˆ

1. β(θ) not flat

(i.e. sensitive to changes in θ)

ˆ

2. β(θ) not dispersed (i.e. robust agains changes in ys (θ))

[Frigessi & Heggland, 2004]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-61-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

ABC using indirect inference

We present a novel approach for developing summary statistics

for use in approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) algorithms by

using indirect inference(...) In the indirect inference approach to

ABC the parameters of an auxiliary model fitted to the data become

the summary statistics. Although applicable to any ABC technique,

we embed this approach within a sequential Monte Carlo algorithm

that is completely adaptive and requires very little tuning(...)

[Drovandi, Pettitt & Faddy, 2011]

c Indirect inference provides summary statistics for ABC...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-62-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

simulation-based methods in Econometrics

ABC using indirect inference

...the above result shows that, in the limit as h → 0, ABC will

be more accurate than an indirect inference method whose auxiliary

statistics are the same as the summary statistic that is used for

ABC(...) Initial analysis showed that which method is more

accurate depends on the true value of θ.

[Fearnhead and Prangle, 2012]

c Indirect inference provides estimates rather than global inference...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-63-320.jpg)

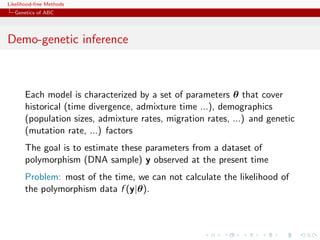

![Likelihood-free Methods

Genetics of ABC

Genetic background of ABC

ABC is a recent computational technique that only requires being

able to sample from the likelihood f (·|θ)

This technique stemmed from population genetics models, about

15 years ago, and population geneticists still contribute

significantly to methodological developments of ABC.

[Griffith & al., 1997; Tavar´ & al., 1999]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-64-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Genetics of ABC

Population genetics

[Part derived from the teaching material of Raphael Leblois, ENS Lyon, November 2010]

Describe the genotypes, estimate the alleles frequencies,

determine their distribution among individuals, populations

and between populations;

Predict and understand the evolution of gene frequencies in

populations as a result of various factors.

c Analyses the effect of various evolutive forces (mutation, drift,

migration, selection) on the evolution of gene frequencies in time

and space.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-65-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Genetics of ABC

A[B]ctors

Les mécanismes de l’évolution

Towards an explanation of the mechanisms of evolutionary

changes, mathematical models ofl’évolution ont to be developed

•! Les mathématiques de evolution started

in the years 1920-1930.

commencé à être développés dans les

années 1920-1930

Ronald A Fisher (1890-1962) Sewall Wright (1889-1988) John BS Haldane (1892-1964)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-66-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Genetics of ABC

Coalescent theory

[Kingman, 1982; Tajima, Tavar´, &tc]

e

!"#$%&'(('")**+$,-'".'"/010234%'".'5"*$*%()23$15"6"

Coalescence theory interested in the genealogy of a sample of

!!7**+$,-'",()5534%'" common ancestor of the sample.

"

genes back in time to the " "!"7**+$,-'"8",$)('5,'1,'"9"](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-68-320.jpg)

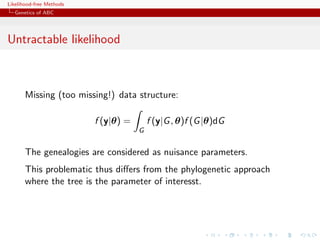

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Illustrations

Example

Inference on CMB: in cosmology, study of the Cosmic Microwave

Background via likelihoods immensely slow to computate (e.g

WMAP, Plank), because of numerically costly spectral transforms

[Data is a Fortran program]

[Kilbinger et al., 2010, MNRAS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-82-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Illustrations

Example

Phylogenetic tree: in population

genetics, reconstitution of a common

ancestor from a sample of genes via

a phylogenetic tree that is close to

impossible to integrate out

[100 processor days with 4

parameters]

[Cornuet et al., 2009, Bioinformatics]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-83-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

The ABC method

Bayesian setting: target is π(θ)f (x|θ)

When likelihood f (x|θ) not in closed form, likelihood-free rejection

technique:

ABC algorithm

For an observation y ∼ f (y|θ), under the prior π(θ), keep jointly

simulating

θ ∼ π(θ) , z ∼ f (z|θ ) ,

until the auxiliary variable z is equal to the observed value, z = y.

[Tavar´ et al., 1997]

e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-86-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Why does it work?!

The proof is trivial:

f (θi ) ∝ π(θi )f (z|θi )Iy (z)

z∈D

∝ π(θi )f (y|θi )

= π(θi |y) .

[Accept–Reject 101]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-87-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Earlier occurrence

‘Bayesian statistics and Monte Carlo methods are ideally

suited to the task of passing many models over one

dataset’

[Don Rubin, Annals of Statistics, 1984]

Note Rubin (1984) does not promote this algorithm for

likelihood-free simulation but frequentist intuition on posterior

distributions: parameters from posteriors are more likely to be

those that could have generated the data.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-88-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

A as A...pproximative

When y is a continuous random variable, equality z = y is replaced

with a tolerance condition,

(y, z) ≤

where is a distance

Output distributed from

π(θ) Pθ { (y, z) < } ∝ π(θ| (y, z) < )

[Pritchard et al., 1999]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-90-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Convergence of ABC (first attempt)

What happens when → 0?

If f (·|θ) is continuous in y , uniformly in θ [!], given an arbitrary

δ > 0, there exists 0 such that < 0 implies

π(θ) f (z|θ)IA ,y (z) dz π(θ)f (y|θ)(1 δ)µ(B )

∈

A ,y ×Θ π(θ)f (z|θ)dzdθ Θ π(θ)f (y|θ)dθ(1 ± δ)µ(B )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-95-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Convergence of ABC (first attempt)

What happens when → 0?

If f (·|θ) is continuous in y , uniformly in θ [!], given an arbitrary

δ > 0, there exists 0 such that < 0 implies

π(θ) f (z|θ)IA ,y (z) dz π(θ)f (y|θ)(1 δ)

XX )

µ(BX

∈

A ,y ×Θ π(θ)f (z|θ)dzdθ Θ π(θ)f (y|θ)dθ(1 ± δ)

µ(B )

XXX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-96-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Convergence of ABC (first attempt)

What happens when → 0?

If f (·|θ) is continuous in y , uniformly in θ [!], given an arbitrary

δ 0, there exists 0 such that 0 implies

π(θ) f (z|θ)IA ,y (z) dz π(θ)f (y|θ)(1 δ)

XX )

µ(BX

∈

A ,y ×Θ π(θ)f (z|θ)dzdθ Θ π(θ)f (y|θ)dθ(1 ± δ) X

µ(B )

X

X

[Proof extends to other continuous-in-0 kernels K ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-97-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

MA example

Back to the MA(q) model

q

xt = t + ϑi t−i

i=1

Simple prior: uniform over the inverse [real and complex] roots in

q

Q(u) = 1 − ϑi u i

i=1

under the identifiability conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-105-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

Homonomy

The ABC algorithm is not to be confused with the ABC algorithm

The Artificial Bee Colony algorithm is a swarm based meta-heuristic

algorithm that was introduced by Karaboga in 2005 for optimizing

numerical problems. It was inspired by the intelligent foraging

behavior of honey bees. The algorithm is specifically based on the

model proposed by Tereshko and Loengarov (2005) for the foraging

behaviour of honey bee colonies. The model consists of three

essential components: employed and unemployed foraging bees, and

food sources. The first two components, employed and unemployed

foraging bees, search for rich food sources (...) close to their hive.

The model also defines two leading modes of behaviour (...):

recruitment of foragers to rich food sources resulting in positive

feedback and abandonment of poor sources by foragers causing

negative feedback.

[Karaboga, Scholarpedia]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-112-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

ABC advances

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y ...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-114-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

ABC advances

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y ...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-115-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

ABC basics

ABC advances

Simulating from the prior is often poor in efficiency

Either modify the proposal distribution on θ to increase the density

of x’s within the vicinity of y ...

[Marjoram et al, 2003; Bortot et al., 2007, Sisson et al., 2007]

...or by viewing the problem as a conditional density estimation

and by developing techniques to allow for larger

[Beaumont et al., 2002]

.....or even by including in the inferential framework [ABCµ ]

[Ratmann et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-116-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP

Better usage of [prior] simulations by

adjustement: instead of throwing away

θ such that ρ(η(z), η(y)) , replace

θ’s with locally regressed transforms

(use with BIC)

θ∗ = θ − {η(z) − η(y)}T β

ˆ [Csill´ry et al., TEE, 2010]

e

ˆ

where β is obtained by [NP] weighted least square regression on

(η(z) − η(y)) with weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z), η(y))}

[Beaumont et al., 2002, Genetics]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-117-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (regression)

Also found in the subsequent literature, e.g. in Fearnhead-Prangle (2012) :

weight directly simulation by

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

or

S

1

Kδ {ρ(η(zs (θ)), η(y))}

S

s=1

[consistent estimate of f (η|θ)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-118-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (regression)

Also found in the subsequent literature, e.g. in Fearnhead-Prangle (2012) :

weight directly simulation by

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

or

S

1

Kδ {ρ(η(zs (θ)), η(y))}

S

s=1

[consistent estimate of f (η|θ)]

Curse of dimensionality: poor estimate when d = dim(η) is large...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-119-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (density estimation)

Use of the kernel weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

leads to the NP estimate of the posterior expectation

i θi Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-120-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (density estimation)

Use of the kernel weights

Kδ {ρ(η(z(θ)), η(y))}

leads to the NP estimate of the posterior conditional density

˜

Kb (θi − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-121-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (density estimations)

Other versions incorporating regression adjustments

˜

Kb (θi∗ − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

In all cases, error

E[ˆ (θ|y)] − g (θ|y) = cb 2 + cδ 2 + OP (b 2 + δ 2 ) + OP (1/nδ d )

g

c

var(ˆ (θ|y)) =

g (1 + oP (1))

nbδ d

[Blum, JASA, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-123-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NP (density estimations)

Other versions incorporating regression adjustments

˜

Kb (θi∗ − θ)Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

i

i Kδ {ρ(η(z(θi )), η(y))}

In all cases, error

E[ˆ (θ|y)] − g (θ|y) = cb 2 + cδ 2 + OP (b 2 + δ 2 ) + OP (1/nδ d )

g

c

var(ˆ (θ|y)) =

g (1 + oP (1))

nbδ d

[standard NP calculations]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-124-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NCH

Incorporating non-linearities and heterocedasticities:

σ (η(y))

ˆ

θ∗ = m(η(y)) + [θ − m(η(z))]

ˆ ˆ

σ (η(z))

ˆ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-125-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NCH

Incorporating non-linearities and heterocedasticities:

σ (η(y))

ˆ

θ∗ = m(η(y)) + [θ − m(η(z))]

ˆ ˆ

σ (η(z))

ˆ

where

m(η) estimated by non-linear regression (e.g., neural network)

ˆ

σ (η) estimated by non-linear regression on residuals

ˆ

log{θi − m(ηi )}2 = log σ 2 (ηi ) + ξi

ˆ

[Blum Fran¸ois, 2009]

c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-126-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-NCH (2)

Why neural network?

fights curse of dimensionality

selects relevant summary statistics

provides automated dimension reduction

offers a model choice capability

improves upon multinomial logistic

[Blum Fran¸ois, 2009]

c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-128-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-MCMC

Markov chain (θ(t) ) created via the transition function

θ ∼ Kω (θ |θ(t) ) if x ∼ f (x|θ ) is such that x = y

π(θ )Kω (t) |θ )

θ (t+1)

= and u ∼ U(0, 1) ≤ π(θ(t) )K (θ |θ(t) ) ,

ω (θ

(t)

θ otherwise,

has the posterior π(θ|y ) as stationary distribution

[Marjoram et al, 2003]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-130-320.jpg)

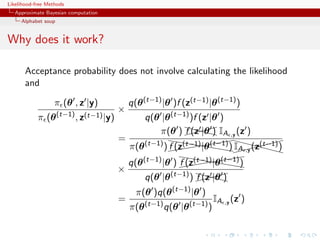

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-MCMC (2)

Algorithm 2 Likelihood-free MCMC sampler

Use Algorithm 1 to get (θ(0) , z(0) )

for t = 1 to N do

Generate θ from Kω ·|θ(t−1) ,

Generate z from the likelihood f (·|θ ),

Generate u from U[0,1] ,

π(θ )Kω (θ(t−1) |θ )

if u ≤ I

π(θ(t−1) Kω (θ |θ(t−1) ) A ,y (z ) then

set (θ(t) , z(t) ) = (θ , z )

else

(θ(t) , z(t) )) = (θ(t−1) , z(t−1) ),

end if

end for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-131-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

A toy example

Case of

1 1

x ∼ N (θ, 1) + N (θ, 1)

2 2

under prior θ ∼ N (0, 10)

ABC sampler

thetas=rnorm(N,sd=10)

zed=sample(c(1,-1),N,rep=TRUE)*thetas+rnorm(N,sd=1)

eps=quantile(abs(zed-x),.01)

abc=thetas[abs(zed-x)eps]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-136-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

A toy example

Case of

1 1

x ∼ N (θ, 1) + N (θ, 1)

2 2

under prior θ ∼ N (0, 10)

ABC-MCMC sampler

metas=rep(0,N)

metas[1]=rnorm(1,sd=10)

zed[1]=x

for (t in 2:N){

metas[t]=rnorm(1,mean=metas[t-1],sd=5)

zed[t]=rnorm(1,mean=(1-2*(runif(1).5))*metas[t],sd=1)

if ((abs(zed[t]-x)eps)||(runif(1)dnorm(metas[t],sd=10)/dnorm(metas[t-1],sd=10))){

metas[t]=metas[t-1]

zed[t]=zed[t-1]}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-137-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ

[Ratmann, Andrieu, Wiuf and Richardson, 2009, PNAS]

Use of a joint density

f (θ, |y) ∝ ξ( |y, θ) × πθ (θ) × π ( )

where y is the data, and ξ( |y, θ) is the prior predictive density of

ρ(η(z), η(y)) given θ and x when z ∼ f (z|θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-144-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ

[Ratmann, Andrieu, Wiuf and Richardson, 2009, PNAS]

Use of a joint density

f (θ, |y) ∝ ξ( |y, θ) × πθ (θ) × π ( )

where y is the data, and ξ( |y, θ) is the prior predictive density of

ρ(η(z), η(y)) given θ and x when z ∼ f (z|θ)

Warning! Replacement of ξ( |y, θ) with a non-parametric kernel

approximation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-145-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ details

Multidimensional distances ρk (k = 1, . . . , K ) and errors

k = ρk (ηk (z), ηk (y)), with

ˆ 1

k ∼ ξk ( |y, θ) ≈ ξk ( |y, θ) = K [{ k −ρk (ηk (zb ), ηk (y))}/hk ]

Bhk

b

ˆ

then used in replacing ξ( |y, θ) with mink ξk ( |y, θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-146-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ details

Multidimensional distances ρk (k = 1, . . . , K ) and errors

k = ρk (ηk (z), ηk (y)), with

ˆ 1

k ∼ ξk ( |y, θ) ≈ ξk ( |y, θ) = K [{ k −ρk (ηk (zb ), ηk (y))}/hk ]

Bhk

b

ˆ

then used in replacing ξ( |y, θ) with mink ξk ( |y, θ)

ABCµ involves acceptance probability

ˆ

π(θ , ) q(θ , θ)q( , ) mink ξk ( |y, θ )

ˆ

π(θ, ) q(θ, θ )q( , ) mink ξk ( |y, θ)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-147-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ multiple errors

[ c Ratmann et al., PNAS, 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-148-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABCµ for model choice

[ c Ratmann et al., PNAS, 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-149-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Questions about ABCµ

For each model under comparison, marginal posterior on used to

assess the fit of the model (HPD includes 0 or not).

Is the data informative about ? [Identifiability]

How is the prior π( ) impacting the comparison?

How is using both ξ( |x0 , θ) and π ( ) compatible with a

standard probability model? [remindful of Wilkinson ]

Where is the penalisation for complexity in the model

comparison?

[X, Mengersen Chen, 2010, PNAS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-151-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-PRC

Another sequential version producing a sequence of Markov

(t) (t)

transition kernels Kt and of samples (θ1 , . . . , θN ) (1 ≤ t ≤ T )

ABC-PRC Algorithm

(t−1)

1. Select θ at random from previous θi ’s with probabilities

(t−1)

ωi (1 ≤ i ≤ N).

2. Generate

(t) (t)

θi ∼ Kt (θ|θ ) , x ∼ f (x|θi ) ,

3. Check that (x, y ) , otherwise start again.

[Sisson et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-153-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Why PRC?

Partial rejection control: Resample from a population of weighted

particles by pruning away particles with weights below threshold C ,

replacing them by new particles obtained by propagating an

existing particle by an SMC step and modifying the weights

accordinly.

[Liu, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-154-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Why PRC?

Partial rejection control: Resample from a population of weighted

particles by pruning away particles with weights below threshold C ,

replacing them by new particles obtained by propagating an

existing particle by an SMC step and modifying the weights

accordinly.

[Liu, 2001]

PRC justification in ABC-PRC:

Suppose we then implement the PRC algorithm for some

c 0 such that only identically zero weights are smaller

than c

Trouble is, there is no such c...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-155-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-PRC bias

Lack of unbiasedness of the method

Joint density of the accepted pair (θ(t−1) , θ(t) ) proportional to

(t−1) (t) (t−1) (t)

π(θ |y )Kt (θ |θ )f (y |θ ),

For an arbitrary function h(θ), E [ωt h(θ(t) )] proportional to

(t) π(θ (t) )Lt−1 (θ (t−1) |θ (t) ) (t−1) (t) (t−1) (t) (t−1) (t)

h(θ ) π(θ |y )Kt (θ |θ )f (y |θ )dθ dθ

π(θ (t−1) )Kt (θ (t) |θ (t−1) )

(t) π(θ (t) )Lt−1 (θ (t−1) |θ (t) ) (t−1) (t−1)

∝ h(θ ) π(θ )f (y |θ )

π(θ (t−1) )Kt (θ (t) |θ (t−1) )

(t) (t−1) (t) (t−1) (t)

× Kt (θ |θ )f (y |θ )dθ dθ

(t) (t) (t−1) (t) (t−1) (t−1) (t)

∝ h(θ )π(θ |y ) Lt−1 (θ |θ )f (y |θ )dθ dθ .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-160-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

A mixture example (1)

Toy model of Sisson et al. (2007): if

θ ∼ U(−10, 10) , x|θ ∼ 0.5 N (θ, 1) + 0.5 N (θ, 1/100) ,

then the posterior distribution associated with y = 0 is the normal

mixture

θ|y = 0 ∼ 0.5 N (0, 1) + 0.5 N (0, 1/100)

restricted to [−10, 10].

Furthermore, true target available as

π(θ||x| ) ∝ Φ( −θ)−Φ(− −θ)+Φ(10( −θ))−Φ(−10( +θ)) .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-161-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

A PMC version

Use of the same kernel idea as ABC-PRC but with IS correction

( check PMC )

Generate a sample at iteration t by

N

(t) (t−1) (t−1)

πt (θ

ˆ )∝ ωj Kt (θ(t) |θj )

j=1

modulo acceptance of the associated xt , and use an importance

(t)

weight associated with an accepted simulation θi

(t) (t) (t)

ωi ∝ π(θi ) πt (θi ) .

ˆ

c Still likelihood free

[Beaumont et al., 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-163-320.jpg)

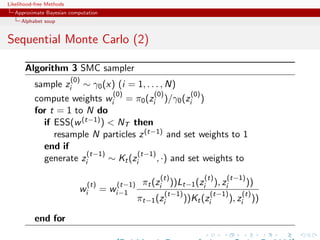

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Sequential Monte Carlo

SMC is a simulation technique to approximate a sequence of

related probability distributions πn with π0 “easy” and πT as

target.

Iterated IS as PMC: particles moved from time n to time n via

kernel Kn and use of a sequence of extended targets πn˜

n

πn (z0:n ) = πn (zn )

˜ Lj (zj+1 , zj )

j=0

where the Lj ’s are backward Markov kernels [check that πn (zn ) is a

marginal]

[Del Moral, Doucet Jasra, Series B, 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-165-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-SMC

[Del Moral, Doucet Jasra, 2009]

True derivation of an SMC-ABC algorithm

Use of a kernel Kn associated with target π n and derivation of the

backward kernel

π n (z )Kn (z , z)

Ln−1 (z, z ) =

πn (z)

Update of the weights

M m

m=1 IA n

(xin )

win ∝ wi(n−1) M m

(xi(n−1) )

m=1 IA n−1

m

when xin ∼ K (xi(n−1) , ·)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-167-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-SMCM

Modification: Makes M repeated simulations of the pseudo-data z

given the parameter, rather than using a single [M = 1] simulation,

leading to weight that is proportional to the number of accepted

zi s

M

1

ω(θ) = Iρ(η(y),η(zi ))

M

i=1

[limit in M means exact simulation from (tempered) target]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-168-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Properties of ABC-SMC

The ABC-SMC method properly uses a backward kernel L(z, z ) to

simplify the importance weight and to remove the dependence on

the unknown likelihood from this weight. Update of importance

weights is reduced to the ratio of the proportions of surviving

particles

Major assumption: the forward kernel K is supposed to be invariant

against the true target [tempered version of the true posterior]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-169-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Properties of ABC-SMC

The ABC-SMC method properly uses a backward kernel L(z, z ) to

simplify the importance weight and to remove the dependence on

the unknown likelihood from this weight. Update of importance

weights is reduced to the ratio of the proportions of surviving

particles

Major assumption: the forward kernel K is supposed to be invariant

against the true target [tempered version of the true posterior]

Adaptivity in ABC-SMC algorithm only found in on-line

construction of the thresholds t , slowly enough to keep a large

number of accepted transitions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-170-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Yet another ABC-PRC

Another version of ABC-PRC called PRC-ABC with a proposal

distribution Mt , S replications of the pseudo-data, and a PRC step:

PRC-ABC Algorithm

(t−1) (t−1)

1. Select θ at random from the θi ’s with probabilities ωi

(t) iid (t−1)

2. Generate θi ∼ Kt , x1 , . . . , xS ∼ f (x|θi ), set

(t) (t)

ωi = Kt {η(xs ) − η(y)} Kt (θi ) ,

s

(t)

and accept with probability p (i) = ωi /ct,N

(t) (t)

3. Set ωi ∝ ωi /p (i) (1 ≤ i ≤ N)

[Peters, Sisson Fan, Stat Computing, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-172-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Wilkinson’s exact BC

ABC approximation error (i.e. non-zero tolerance) replaced with

exact simulation from a controlled approximation to the target,

convolution of true posterior with kernel function

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)

π (θ, z|y) = ,

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)dzdθ

with K kernel parameterised by bandwidth .

[Wilkinson, 2008]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-174-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Wilkinson’s exact BC

ABC approximation error (i.e. non-zero tolerance) replaced with

exact simulation from a controlled approximation to the target,

convolution of true posterior with kernel function

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)

π (θ, z|y) = ,

π(θ)f (z|θ)K (y − z)dzdθ

with K kernel parameterised by bandwidth .

[Wilkinson, 2008]

Theorem

The ABC algorithm based on the assumption of a randomised

observation y = y + ξ, ξ ∼ K , and an acceptance probability of

˜

K (y − z)/M

gives draws from the posterior distribution π(θ|y).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-175-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

How exact a BC?

“Using to represent measurement error is

straightforward, whereas using to model the model

discrepancy is harder to conceptualize and not as

commonly used”

[Richard Wilkinson, 2008]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-176-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

How exact a BC?

Pros

Pseudo-data from true model and observed data from noisy

model

Interesting perspective in that outcome is completely

controlled

Link with ABCµ and assuming y is observed with a

measurement error with density K

Relates to the theory of model approximation

[Kennedy O’Hagan, 2001]

Cons

Requires K to be bounded by M

True approximation error never assessed

Requires a modification of the standard ABC algorithm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-177-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC for HMMs

Specific case of a hidden Markov model

Xt+1 ∼ Qθ (Xt , ·)

Yt+1 ∼ gθ (·|xt )

0

where only y1:n is observed.

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, Peters, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-178-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC for HMMs

Specific case of a hidden Markov model

Xt+1 ∼ Qθ (Xt , ·)

Yt+1 ∼ gθ (·|xt )

0

where only y1:n is observed.

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, Peters, 2011]

Use of specific constraints, adapted to the Markov structure:

0 0

y1 ∈ B(y1 , ) × · · · × yn ∈ B(yn , )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-179-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-MLE for HMMs

ABC-MLE defined by

ˆ 0 0

θn = arg max Pθ Y1 ∈ B(y1 , ), . . . , Yn ∈ B(yn , )

θ

Exact MLE for the likelihood same basis as Wilkinson!

0

pθ (y1 , . . . , yn )

corresponding to the perturbed process

(xt , yt + zt )1≤t≤n zt ∼ U(B(0, 1)

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, Peters, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-181-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-MLE is biased

ABC-MLE is asymptotically (in n) biased with target

l (θ) = Eθ∗ [log pθ (Y1 |Y−∞:0 )]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-182-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

ABC-MLE is biased

ABC-MLE is asymptotically (in n) biased with target

l (θ) = Eθ∗ [log pθ (Y1 |Y−∞:0 )]

but ABD-MLE converges to true value in the sense

l n (θn ) → l (θ)

for all sequences (θn ) converging to θ and n](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-183-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Noisy ABC-MLE

Idea: Modify instead the data from the start

0

(y1 + ζ1 , . . . , yn + ζn )

[ see Fearnhead-Prangle ]

noisy ABC-MLE estimate

0 0

arg max Pθ Y1 ∈ B(y1 + ζ1 , ), . . . , Yn ∈ B(yn + ζn , )

θ

[Dean, Singh, Jasra, Peters, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-184-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

SMC for ABC likelihood

Algorithm 4 SMC ABC for HMMs

Given θ

for k = 1, . . . , n do

1 1 N N

generate proposals (xk , yk ), . . . , (xk , yk ) from the model

weigh each proposal with ωk l =I l

B(yk + ζk , ) (yk )

0

l

renormalise the weights and sample the xk ’s accordingly

end for

approximate the likelihood by

n N

l

ωk N

k=1 l=1

[Jasra, Singh, Martin, McCoy, 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-186-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Which summary?

Fundamental difficulty of the choice of the summary statistic when

there is no non-trivial sufficient statistics [except when done by the

experimenters in the field]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-187-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Which summary?

Fundamental difficulty of the choice of the summary statistic when

there is no non-trivial sufficient statistics [except when done by the

experimenters in the field]

Starting from a large collection of summary statistics is available,

Joyce and Marjoram (2008) consider the sequential inclusion into

the ABC target, with a stopping rule based on a likelihood ratio

test.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-188-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

Which summary?

Fundamental difficulty of the choice of the summary statistic when

there is no non-trivial sufficient statistics [except when done by the

experimenters in the field]

Starting from a large collection of summary statistics is available,

Joyce and Marjoram (2008) consider the sequential inclusion into

the ABC target, with a stopping rule based on a likelihood ratio

test.

Does not taking into account the sequential nature of the tests

Depends on parameterisation

Order of inclusion matters.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-189-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Alphabet soup

A connected Monte Carlo study

of the pseudo-data per simulated parameter

Repeating simulations

does not improve approximation

Tolerance level does not seem to be highly influential

Choice of distance / summary statistics / calibration factors

are paramount to successful approximation

ABC-SMC outperforms ABC-MCMC

[Mckinley, Cook, Deardon, 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-190-320.jpg)

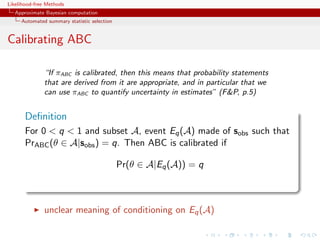

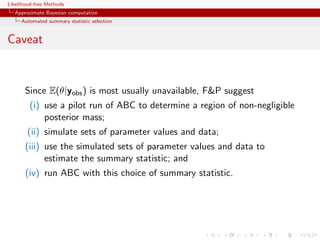

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Semi-automatic ABC

Fearnhead and Prangle (2010) study ABC and the selection of the

summary statistic in close proximity to Wilkinson’s proposal

ABC then considered from a purely inferential viewpoint and

calibrated for estimation purposes.

Use of a randomised (or ‘noisy’) version of the summary statistics

η (y) = η(y) + τ

˜

Derivation of a well-calibrated version of ABC, i.e. an algorithm

that gives proper predictions for the distribution associated with

this randomised summary statistic. [calibration constraint: ABC

approximation with same posterior mean as the true randomised

posterior.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-192-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Summary statistics

Optimality of the posterior expectation E[θ|y] of the parameter of

interest as summary statistics η(y)!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-193-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Summary statistics

Optimality of the posterior expectation E[θ|y] of the parameter of

interest as summary statistics η(y)!

Use of the standard quadratic loss function

(θ − θ0 )T A(θ − θ0 ) .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-194-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Details on Fearnhead and Prangle (FP) ABC

Use of a summary statistic S(·), an importance proposal g (·), a

kernel K (·) ≤ 1 and a bandwidth h 0 such that

(θ, ysim ) ∼ g (θ)f (ysim |θ)

is accepted with probability (hence the bound)

K [{S(ysim ) − sobs }/h]

and the corresponding importance weight defined by

π(θ) g (θ)

[Fearnhead Prangle, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-195-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Errors, errors, and errors

Three levels of approximation

π(θ|yobs ) by π(θ|sobs ) loss of information

[ignored]

π(θ|sobs ) by

π(s)K [{s − sobs }/h]π(θ|s) ds

πABC (θ|sobs ) =

π(s)K [{s − sobs }/h] ds

noisy observations

πABC (θ|sobs ) by importance Monte Carlo based on N

simulations, represented by var(a(θ)|sobs )/Nacc [expected

number of acceptances]

[M. Twain/B. Disraeli]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-196-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Average acceptance asymptotics

For the average acceptance probability/approximate likelihood

p(θ|sobs ) = f (ysim |θ) K [{S(ysim ) − sobs }/h] dysim ,

overall acceptance probability

p(sobs ) = p(θ|sobs ) π(θ) dθ = π(sobs )hd + o(hd )

[FP, Lemma 1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-197-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Optimal importance proposal

Best choice of importance proposal in terms of effective sample size

g (θ|sobs ) ∝ π(θ)p(θ|sobs )1/2

[Not particularly useful in practice]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-198-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Optimal importance proposal

Best choice of importance proposal in terms of effective sample size

g (θ|sobs ) ∝ π(θ)p(θ|sobs )1/2

[Not particularly useful in practice]

note that p(θ|sobs ) is an approximate likelihood

reminiscent of parallel tempering

could be approximately achieved by attrition of half of the

data](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-199-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Calibration of h

“This result gives insight into how S(·) and h affect the Monte

Carlo error. To minimize Monte Carlo error, we need hd to be not

too small. Thus ideally we want S(·) to be a low dimensional

summary of the data that is sufficiently informative about θ that

π(θ|sobs ) is close, in some sense, to π(θ|yobs )” (FP, p.5)

turns h into an absolute value while it should be

context-dependent and user-calibrated

only addresses one term in the approximation error and

acceptance probability (“curse of dimensionality”)

h large prevents πABC (θ|sobs ) to be close to π(θ|sobs )

d small prevents π(θ|sobs ) to be close to π(θ|yobs ) (“curse of

[dis]information”)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-200-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Calibrated ABC

Theorem (FP)

Noisy ABC, where

sobs = S(yobs ) + h , ∼ K (·)

is calibrated

[Wilkinson, 2008]

no condition on h!!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-203-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

More about calibrated ABC

“Calibration is not universally accepted by Bayesians. It is even more

questionable here as we care how statements we make relate to the

real world, not to a mathematically defined posterior.” R. Wilkinson

Same reluctance about the prior being calibrated

Property depending on prior, likelihood, and summary

Calibration is a frequentist property (almost a p-value!)

More sensible to account for the simulator’s imperfections

than using noisy-ABC against a meaningless based measure

[Wilkinson, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-205-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Converging ABC

Theorem (FP)

For noisy ABC, the expected noisy-ABC log-likelihood,

E {log[p(θ|sobs )]} = log[p(θ|S(yobs ) + )]π(yobs |θ0 )K ( )dyobs d ,

has its maximum at θ = θ0 .

True for any choice of summary statistic? even ancilary statistics?!

[Imposes at least identifiability...]

Relevant in asymptotia and not for the data](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-206-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Converging ABC

Corollary

For noisy ABC, the ABC posterior converges onto a point mass on

the true parameter value as m → ∞.

For standard ABC, not always the case (unless h goes to zero).

Strength of regularity conditions (c1) and (c2) in Bernardo

Smith, 1994?

[out-of-reach constraints on likelihood and posterior]

Again, there must be conditions imposed upon summary

statistics...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-207-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Loss motivated statistic

Under quadratic loss function,

Theorem (FP)

ˆ

(i) The minimal posterior error E[L(θ, θ)|yobs ] occurs when

ˆ = E(θ|yobs ) (!)

θ

(ii) When h → 0, EABC (θ|sobs ) converges to E(θ|yobs )

ˆ

(iii) If S(yobs ) = E[θ|yobs ] then for θ = EABC [θ|sobs ]

ˆ

E[L(θ, θ)|yobs ] = trace(AΣ) + h2 xT AxK (x)dx + o(h2 ).

measure-theoretic difficulties?

dependence of sobs on h makes me uncomfortable inherent to noisy

ABC

Relevant for choice of K ?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-208-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Optimal summary statistic

“We take a different approach, and weaken the requirement for

πABC to be a good approximation to π(θ|yobs ). We argue for πABC

to be a good approximation solely in terms of the accuracy of

certain estimates of the parameters.” (FP, p.5)

From this result, FP

derive their choice of summary statistic,

S(y) = E(θ|y)

[almost sufficient]

suggest

h = O(N −1/(2+d) ) and h = O(N −1/(4+d) )

as optimal bandwidths for noisy and standard ABC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-209-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Optimal summary statistic

“We take a different approach, and weaken the requirement for

πABC to be a good approximation to π(θ|yobs ). We argue for πABC

to be a good approximation solely in terms of the accuracy of

certain estimates of the parameters.” (FP, p.5)

From this result, FP

derive their choice of summary statistic,

S(y) = E(θ|y)

[wow! EABC [θ|S(yobs )] = E[θ|yobs ]]

suggest

h = O(N −1/(2+d) ) and h = O(N −1/(4+d) )

as optimal bandwidths for noisy and standard ABC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-210-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Approximating the summary statistic

As Beaumont et al. (2002) and Blum and Fran¸ois (2010), FP

c

use a linear regression to approximate E(θ|yobs ):

(i)

θi = β0 + β (i) f (yobs ) + i

with f made of standard transforms

[Further justifications?]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-213-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

[my]questions about semi-automatic ABC

dependence on h and S(·) in the early stage

reduction of Bayesian inference to point estimation

approximation error in step (i) not accounted for

not parameterisation invariant

practice shows that proper approximation to genuine posterior

distributions stems from using a (much) larger number of

summary statistics than the dimension of the parameter

the validity of the approximation to the optimal summary

statistic depends on the quality of the pilot run

important inferential issues like model choice are not covered

by this approach.

[Robert, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-214-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

More about semi-automatic ABC

[End of section derived from comments on Read Paper, to appear]

“The apparently arbitrary nature of the choice of summary statistics

has always been perceived as the Achilles heel of ABC.” M.

Beaumont](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-215-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

More about semi-automatic ABC

[End of section derived from comments on Read Paper, to appear]

“The apparently arbitrary nature of the choice of summary statistics

has always been perceived as the Achilles heel of ABC.” M.

Beaumont

“Curse of dimensionality” linked with the increase of the

dimension of the summary statistic

Connection with principal component analysis

[Itan et al., 2010]

Connection with partial least squares

[Wegman et al., 2009]

Beaumont et al. (2002) postprocessed output is used as input

by FP to run a second ABC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-216-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Wood’s alternative

Instead of a non-parametric kernel approximation to the likelihood

1

K {η(yr ) − η(yobs )}

R r

Wood (2010) suggests a normal approximation

η(y(θ)) ∼ Nd (µθ , Σθ )

whose parameters can be approximated based on the R simulations

(for each value of θ).

Parametric versus non-parametric rate [Uh?!]

Automatic weighting of components of η(·) through Σθ

Dependence on normality assumption (pseudo-likelihood?)

[Cornebise, Girolami Kosmidis, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-218-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Reinterpretation and extensions

Reinterpretation of ABC output as joint simulation from

π (x, y |θ) = f (x|θ)¯Y |X (y |x)

¯ π

where

πY |X (y |x) = K (y − x)

¯

Reinterpretation of noisy ABC

if y |y obs ∼ πY |X (·|y obs ), then marginally

¯ ¯

y ∼ πY |θ (·|θ0 )

¯ ¯

c Explain for the consistency of Bayesian inference based on y and π

¯ ¯

[Lee, Andrieu Doucet, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-220-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Reinterpretation and extensions

Also fits within the pseudo-marginal of Andrieu and Roberts (2009)

Algorithm 6 One-hit MCMC-ABC

At time t, with θt = θ:

Sample θ ∼ g (·|θ).

With probability 1 − min 1, π(θ )g(θ |θ)) , set θt+1 = θ and go to

π(θ)g

(θ|θ

time t + 1.

Sample zi ∼ πY |Θ (·|θ ) and xi ∼ πY |Θ (·|θ) for i = 1, . . . until

y ∈ Bh (zi ) and/or y ∈ Bh (xi ).

If y ∈ Bh (zi ) set θt+1 = θ and go to time t + 1.

If y ∈ Bh (xi ) set θt+1 = θ and go to time t + 1.

[Lee, Andrieu Doucet, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-222-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Reinterpretation and extensions

Also fits within the pseudo-marginal of Andrieu and Roberts (2009)

Validation

c The invariant distribution of θ is

πθ|Y (·|y )

¯

for both algorithms.

[Lee, Andrieu Doucet, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-223-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

ABC for Markov chains

Rewriting the posterior as

π(θ)1−n (θ)π(θ|x1 ) π(θ|xt−1 , xt )

where π(θ|xt−1 , xt ) ∝ f (xt |xt−1 , θ)π(θ)

Allows for a stepwise ABC, replacing each π(θ|xt−1 , xt ) by an

ABC approximation

Similarity with FP’s multiple sources of data (and also with

Dean et al., 2011 )

[White et al., 2010, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-225-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Back to sufficiency

Difference between regular sufficiency, equivalent to

π(θ|y) = π(θ|η(y))

for all θ’s and all priors π, and

marginal sufficiency, stated as

π(µ(θ)|y) = π(µ(θ)|η(y))

for all θ’s, the given prior π and a subvector µ(θ)

[Basu, 1977]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-227-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Back to sufficiency

Difference between regular sufficiency, equivalent to

π(θ|y) = π(θ|η(y))

for all θ’s and all priors π, and

marginal sufficiency, stated as

π(µ(θ)|y) = π(µ(θ)|η(y))

for all θ’s, the given prior π and a subvector µ(θ)

[Basu, 1977]

Relates to F P’s main result, but could event be reduced to

conditional sufficiency

π(µ(θ)|yobs ) = π(µ(θ)|η(yobs ))

(if feasible at all...)

[Dawson, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-228-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

ABC and BCa’s

Arguments in favour of a comparison of ABC with bootstrap in the

event π(θ) is not defined from prior information but as

conventional non-informative prior.

[Efron, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-229-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Predictive performances

Instead of posterior means, other aspects of posterior to explore.

E.g., look at minimising loss of information

p(θ, y) p(θ, η(y))

p(θ, y) log dθdy − p(θ, η(y)) log dθdη(y)

p(θ)p(y) p(θ)p(η(y))

for selection of summary statistics.

[Filippi, Barnes, Stumpf, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-230-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Auxiliary variables

Auxiliary variable method avoids computations of untractable

constant in likelihood

˜

f (y|θ) = Zθ f (y|θ)

Introduce pseudo-data z with artificial target g (z|θ, y)

Generate θ ∼ K (θ, θ ) and z ∼ f (z|θ )

Accept with probability

π(θ )f (y|θ )g (z |θ , y) K (θ , θ)f (z|θ)

∧1

π(θ)f (y|θ)g (z|θ, y) K (θ, θ )f (z |θ )

[Møller, Pettitt, Berthelsen, Reeves, 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-232-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Auxiliary variables

Auxiliary variable method avoids computations of untractable

constant in likelihood

˜

f (y|θ) = Zθ f (y|θ)

Introduce pseudo-data z with artificial target g (z|θ, y)

Generate θ ∼ K (θ, θ ) and z ∼ f (z|θ )

Accept with probability

˜ ˜

π(θ )f (y|θ )g (z |θ , y) K (θ , θ)f (z|θ)

∧1

˜ ˜

π(θ)f (y|θ)g (z|θ, y) K (θ, θ )f (z |θ )

[Møller, Pettitt, Berthelsen, Reeves, 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-233-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Auxiliary variables

Auxiliary variable method avoids computations of untractable

constant in likelihood

˜

f (y|θ) = Zθ f (y|θ)

Introduce pseudo-data z with artificial target g (z|θ, y)

Generate θ ∼ K (θ, θ ) and z ∼ f (z|θ )

For Gibbs random fields , existence of a genuine sufficient statistic η(y).

[Møller, Pettitt, Berthelsen, Reeves, 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-234-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Auxiliary variables and ABC

Special case of ABC when

g (z|θ, y) = K (η(bz) − η(y))

˜ ˜ ˜ ˜

f (y|θ )f (z|θ)/f (y|θ)f (z |θ ) replaced by one [or not?!]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-235-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

Auxiliary variables and ABC

Special case of ABC when

g (z|θ, y) = K (η(bz) − η(y))

˜ ˜ ˜ ˜

f (y|θ )f (z|θ)/f (y|θ)f (z |θ ) replaced by one [or not?!]

Consequences

likelihood-free (ABC) versus constant-free (AVM)

in ABC, K (·) should be allowed to depend on θ

for Gibbs random fields, the auxiliary approach should be

prefered to ABC

[Møller, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-236-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

Approximate Bayesian computation

Automated summary statistic selection

ABC and BIC

Idea of applying BIC during the local regression :

Run regular ABC

Select summary statistics during local regression

Recycle the prior simulation sample (reference table) with

those summary statistics

Rerun the corresponding local regression (low cost)

[Pudlo Sedki, 2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-237-320.jpg)

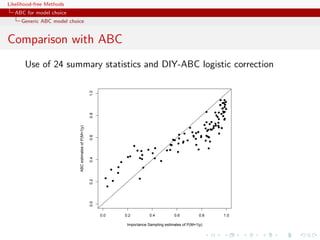

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Model choice

ABC estimates

Posterior probability π(M = m|y) approximated by the frequency

of acceptances from model m

T

1

Im(t) =m .

T

t=1

Extension to a weighted polychotomous logistic regression estimate

of π(M = m|y), with non-parametric kernel weights

[Cornuet et al., DIYABC, 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-243-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Model choice

The Great ABC controversy

On-going controvery in phylogeographic genetics about the validity

of using ABC for testing

Replies: Fagundes et al., 2008,

Against: Templeton, 2008, Beaumont et al., 2010, Berger et

2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c al., 2010, Csill`ry et al., 2010

e

argues that nested hypotheses point out that the criticisms are

cannot have higher probabilities addressed at [Bayesian]

than nesting hypotheses (!) model-based inference and have

nothing to do with ABC...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-245-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Gibbs random fields

Potts model

Potts model

Vc (y) is of the form

Vc (y) = θS(y) = θ δyl =yi

l∼i

where l∼i denotes a neighbourhood structure

In most realistic settings, summation

Zθ = exp{θ T S(x)}

x∈X

involves too many terms to be manageable and numerical

approximations cannot always be trusted

[Cucala, Marin, CPR Titterington, 2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-249-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Gibbs random fields

Sufficient statistics in Gibbs random fields

For Gibbs random fields,

1 2

x|M = m ∼ fm (x|θm ) = fm (x|S(x))fm (S(x)|θm )

1

= f 2 (S(x)|θm )

n(S(x)) m

where

n(S(x)) = {˜ ∈ X : S(˜) = S(x)}

x x

c S(x) is therefore also sufficient for the joint parameters

[Specific to Gibbs random fields!]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-257-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Back to sufficiency

‘Sufficient statistics for individual models are unlikely to

be very informative for the model probability.’

[Scott Sisson, Jan. 31, 2011, X.’Og]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-263-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Back to sufficiency

‘Sufficient statistics for individual models are unlikely to

be very informative for the model probability.’

[Scott Sisson, Jan. 31, 2011, X.’Og]

If η1 (x) sufficient statistic for model m = 1 and parameter θ1 and

η2 (x) sufficient statistic for model m = 2 and parameter θ2 ,

(η1 (x), η2 (x)) is not always sufficient for (m, θm )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-264-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Back to sufficiency

‘Sufficient statistics for individual models are unlikely to

be very informative for the model probability.’

[Scott Sisson, Jan. 31, 2011, X.’Og]

If η1 (x) sufficient statistic for model m = 1 and parameter θ1 and

η2 (x) sufficient statistic for model m = 2 and parameter θ2 ,

(η1 (x), η2 (x)) is not always sufficient for (m, θm )

c Potential loss of information at the testing level](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-265-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Limiting behaviour of B12 (under sufficiency)

If η(y) sufficient statistic for both models,

fi (y|θ i ) = gi (y)fi η (η(y)|θ i )

Thus

Θ1 π(θ 1 )g1 (y)f1η (η(y)|θ 1 ) dθ 1

B12 (y) =

Θ2 π(θ 2 )g2 (y)f2η (η(y)|θ 2 ) dθ 2

g1 (y) π1 (θ 1 )f1η (η(y)|θ 1 ) dθ 1 g1 (y) η

= η = B (y) .

g2 (y) π2 (θ 2 )f2 (η(y)|θ 2 ) dθ 2 g2 (y) 12

[Didelot, Everitt, Johansen Lawson, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-270-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Limiting behaviour of B12 (under sufficiency)

If η(y) sufficient statistic for both models,

fi (y|θ i ) = gi (y)fi η (η(y)|θ i )

Thus

Θ1 π(θ 1 )g1 (y)f1η (η(y)|θ 1 ) dθ 1

B12 (y) =

Θ2 π(θ 2 )g2 (y)f2η (η(y)|θ 2 ) dθ 2

g1 (y) π1 (θ 1 )f1η (η(y)|θ 1 ) dθ 1 g1 (y) η

= η = B (y) .

g2 (y) π2 (θ 2 )f2 (η(y)|θ 2 ) dθ 2 g2 (y) 12

[Didelot, Everitt, Johansen Lawson, 2011]

c No discrepancy only when cross-model sufficiency](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-271-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Formal recovery

Creating an encompassing exponential family

T T

f (x|θ1 , θ2 , α1 , α2 ) ∝ exp{θ1 η1 (x) + θ1 η1 (x) + α1 t1 (x) + α2 t2 (x)}

leads to a sufficient statistic (η1 (x), η2 (x), t1 (x), t2 (x))

[Didelot, Everitt, Johansen Lawson, 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-274-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Formal recovery

Creating an encompassing exponential family

T T

f (x|θ1 , θ2 , α1 , α2 ) ∝ exp{θ1 η1 (x) + θ1 η1 (x) + α1 t1 (x) + α2 t2 (x)}

leads to a sufficient statistic (η1 (x), η2 (x), t1 (x), t2 (x))

[Didelot, Everitt, Johansen Lawson, 2011]

In the Poisson/geometric case, if i xi ! is added to S, no

discrepancy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-275-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Formal recovery

Creating an encompassing exponential family

T T

f (x|θ1 , θ2 , α1 , α2 ) ∝ exp{θ1 η1 (x) + θ1 η1 (x) + α1 t1 (x) + α2 t2 (x)}

leads to a sufficient statistic (η1 (x), η2 (x), t1 (x), t2 (x))

[Didelot, Everitt, Johansen Lawson, 2011]

Only applies in genuine sufficiency settings...

c Inability to evaluate loss brought by summary statistics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-276-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Meaning of the ABC-Bayes factor

‘This is also why focus on model discrimination typically

(...) proceeds by (...) accepting that the Bayes Factor

that one obtains is only derived from the summary

statistics and may in no way correspond to that of the

full model.’

[Scott Sisson, Jan. 31, 2011, X.’Og]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-277-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Meaning of the ABC-Bayes factor

‘This is also why focus on model discrimination typically

(...) proceeds by (...) accepting that the Bayes Factor

that one obtains is only derived from the summary

statistics and may in no way correspond to that of the

full model.’

[Scott Sisson, Jan. 31, 2011, X.’Og]

In the Poisson/geometric case, if E[yi ] = θ0 0,

η (θ0 + 1)2 −θ0

lim B12 (y) = e

n→∞ θ0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-278-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

MA(q) divergence

0.7

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2

Evolution [against ] of ABC Bayes factor, in terms of frequencies of

visits to models MA(1) (left) and MA(2) (right) when equal to

10, 1, .1, .01% quantiles on insufficient autocovariance distances. Sample

of 50 points from a MA(2) with θ1 = 0.6, θ2 = 0.2. True Bayes factor

equal to 17.71.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-279-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

MA(q) divergence

0.8

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2

Evolution [against ] of ABC Bayes factor, in terms of frequencies of

visits to models MA(1) (left) and MA(2) (right) when equal to

10, 1, .1, .01% quantiles on insufficient autocovariance distances. Sample

of 50 points from a MA(1) model with θ1 = 0.6. True Bayes factor B21

equal to .004.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-280-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

Further comments

‘There should be the possibility that for the same model,

but different (non-minimal) [summary] statistics (so

∗

different η’s: η1 and η1 ) the ratio of evidences may no

longer be equal to one.’

[Michael Stumpf, Jan. 28, 2011, ’Og]

Using different summary statistics [on different models] may

indicate the loss of information brought by each set but agreement

does not lead to trustworthy approximations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-281-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

A population genetics evaluation

Population genetics example with

3 populations

2 scenari

15 individuals

5 loci

single mutation parameter

24 summary statistics

2 million ABC proposal

importance [tree] sampling alternative](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romabc-120120013357-phpapp02/85/ABC-in-Roma-283-320.jpg)

![Likelihood-free Methods

ABC for model choice

Generic ABC model choice

The only safe cases???

Besides specific models like Gibbs random fields,

using distances over the data itself escapes the discrepancy...