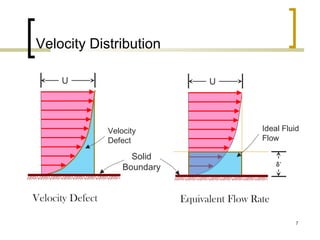

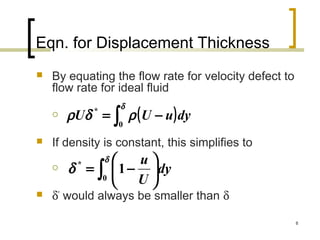

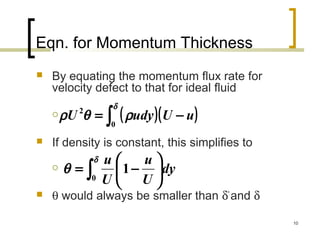

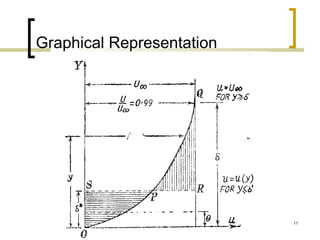

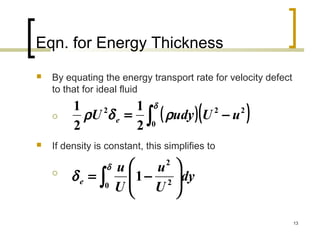

1) The document discusses different definitions of boundary layer thickness, including nominal thickness, displacement thickness, momentum thickness, and energy thickness. Equations are provided for calculating each type of thickness.

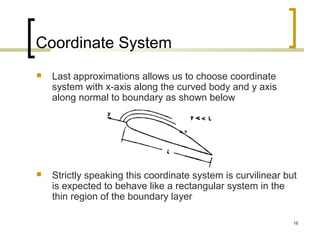

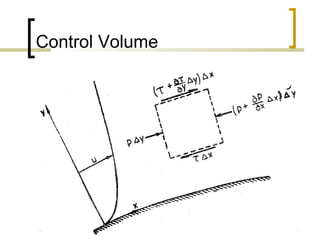

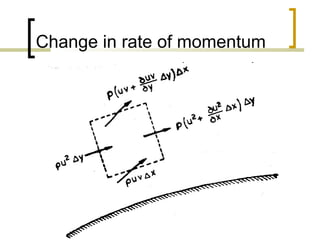

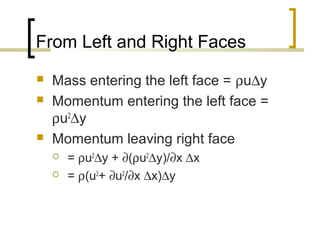

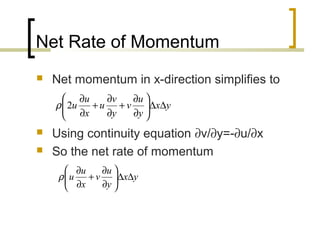

2) Key assumptions of boundary layer theory are that the boundary layer is thin compared to the body and flow is two-dimensional and steady. The Prandtl boundary layer equations are derived using control volume analysis and assumptions of constant density and viscosity.

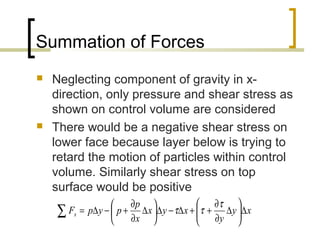

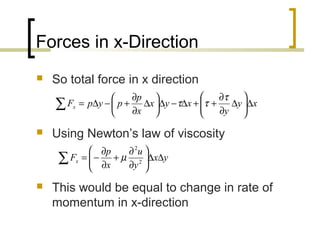

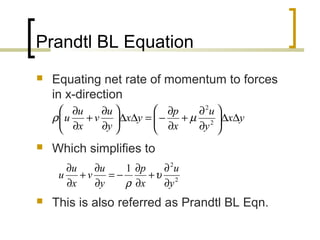

3) The Prandtl boundary layer equation equates forces within the boundary layer, including pressure and shear stress, to the net rate of momentum change and forms the basis for boundary layer analysis.