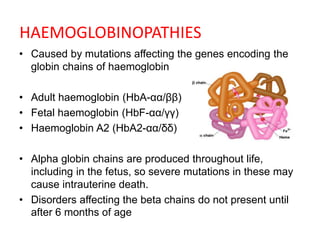

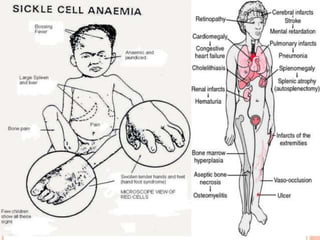

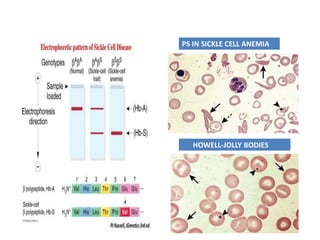

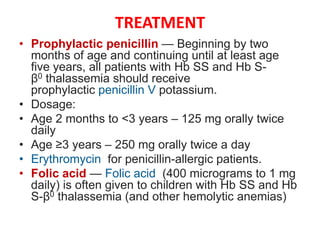

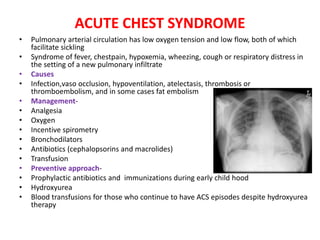

Sickle cell disease is caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene resulting in abnormal hemoglobin S. This leads to polymerization of deoxygenated hemoglobin S and distortion of red blood cells into a sickle shape. Chronic hemolysis and vaso-occlusive crises cause significant morbidity. Diagnosis is made through hemoglobin electrophoresis showing elevated HbS. Treatment involves prophylactic antibiotics, hydration, pain management, hydroxyurea and blood transfusions to reduce complications. Chronic organ damage remains a major cause of mortality in patients with sickle cell disease.

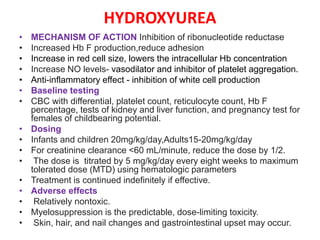

![• Hydroxyurea and other disease-modifying therapies

• It decreases the frequency and severity of vaso-occlusive

complications (eg, dactylitis, painful episodes, acute chest

syndrome [ACS]) and it may reduce the risk of organ damage

in individuals with Hb SS and Hb S-β0 thalassemia.

•

• Options for patients who cannot take hydroxyurea or who

have continued symptoms despite optimally dosed

hydroxyurea include L-glutamine, crizanlizumab,

and voxelotor.

• Education — The child's parents or caregivers should be

educated about acute and chronic complications of SCD

• Routine immunizations plus influenza, pneumococcal and

meningococcal vaccinations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sicklecelldisease-230706042649-1340deb5/85/SICKLE-CELL-DISEASE-pptx-19-320.jpg)

![MULTIORGAN FAILURE

• Acute multiorgan failure is a life-threatening

complication of SCD in which multiple organ

systems are affected by ischemia and/or infarction.

• It is typically seen in the setting of an acute painful

episode

• Complement and other factors have been

implicated.

• Some patients may present with a thrombotic

microangiopathy (TMA, such as thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura [TTP] or complement-

mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome [CM-HUS]

picture), which has led to anecdotal use of

plasmapheresis and complement therapy

• Management of multiorgan failure prompt and

aggressive exchange transfusion therapy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sicklecelldisease-230706042649-1340deb5/85/SICKLE-CELL-DISEASE-pptx-36-320.jpg)