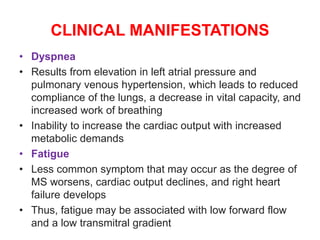

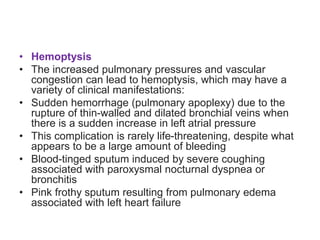

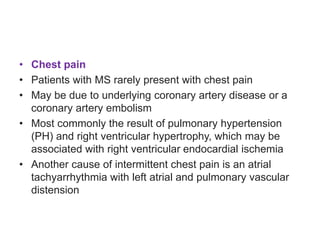

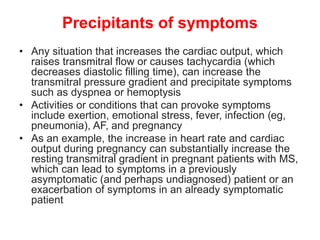

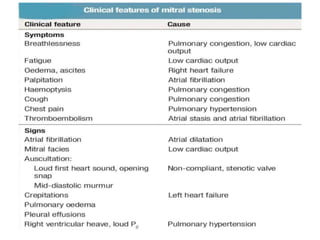

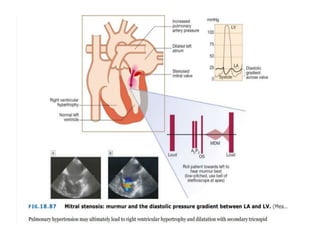

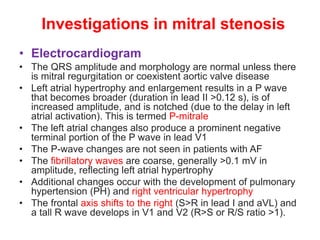

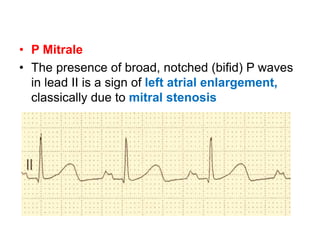

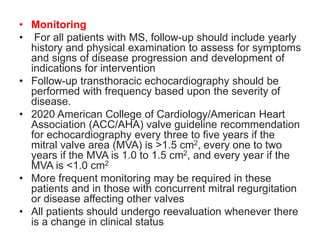

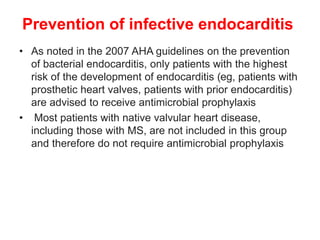

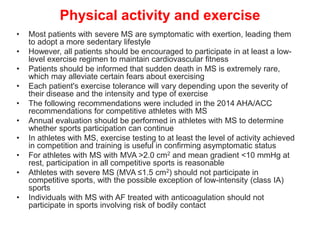

Mitral stenosis is primarily caused by rheumatic fever and can lead to significant cardiac dysfunction, particularly when the mitral valve orifice narrows to less than 2cm2. Clinical manifestations include dyspnea, fatigue, hemoptysis, and occasionally chest pain, often exacerbated by increased cardiac output demands. Management involves patient education, heart failure management, and preventive measures against complications such as thromboembolism and endocarditis.

![Pulmonary hypertension

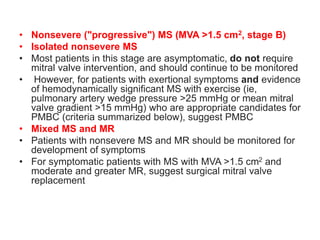

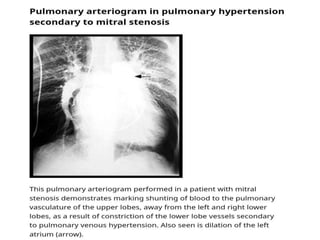

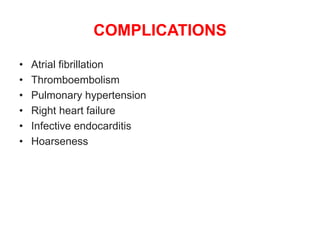

• Patients with MS commonly develop PH (Mean pulmonary artery

pressure [mPAP] >20 mmHg)

• In patients with MS, pulmonary artery pressure elevation is

associated with more severe MS (smaller mitral valve area and

higher mitral valve gradient) and lower atrioventricular compliance

• PH caused by MS is a type of PH due to left heart disease (PH-LHD;

group 2 PH), which is most commonly postcapillary PH but, in a

minority of patients, is combined pre-and postcapillary PH

• Postcapillary PH

• Among patients with MS with PH, most have postcapillary PH due

to chronically elevated pulmonary venous pressure

• The postcapillary PH phenotype is characterized by an mPAP >20

mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure of >15 mmHg, a diastolic

pressure gradient (diastolic pulmonary artery pressure – pulmonary

artery wedge pressure) of <7 mmHg, and a pulmonary vascular

resistance ≤3 Wood units

• Another metric is the transpulmonary gradient (TPG = mPAP –

pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) which is normal (≤12 to 15

mmHg) in patients with postcapillary PH](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-240516103314-049e168c/85/1-MITRAL-STENOSIS-AND-ITS-MANAGEMENT-36-320.jpg)

![• Initial management

• In patients who are hemodynamically unstable,

immediate electrical cardioversion is indicated

• For hemodynamically stable patients, the initial

management consists of controlling the ventricular rate

(with a beta blocker, calcium channel blocker

[verapamil or diltiazem], or, less preferably, digoxin) and

anticoagulation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-240516103314-049e168c/85/1-MITRAL-STENOSIS-AND-ITS-MANAGEMENT-49-320.jpg)

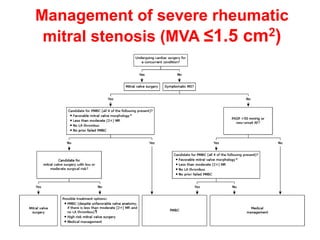

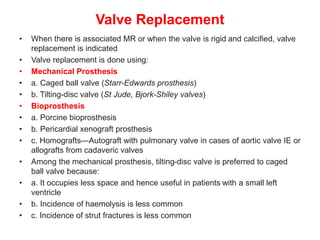

![Indications for intervention

• Decisions on whether and how to intervene are based upon the stage of MS

(which is largely determined by the mitral valve area [MVA] and presence of

symptoms , the feasibility and risk of intervention, and whether the patient is

undergoing cardiac surgery for a concurrent condition

• •Severe MS (MVA ≤1.5 cm2)

• Symptomatic severe MS (stage D)

• For most symptomatic patients (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class

II, III, or IV) with severe rheumatic MS (stage D) , recommend PMBC rather

than either mitral valve surgery or no valve intervention , provided the

patient meets criteria for PMBC

• For those who do not meet criteria for PMBC and are not at high surgical

risk, recommend mitral valve surgery (repair, commissurotomy, or valve

replacement)

• For patients with severe symptomatic rheumatic MS who do not meet

criteria for PMBC and have high surgical risk, management decisions are

individualized

• For patients in this category with severe symptoms (NYHA class III or IV)

and less than moderate mitral regurgitation (MR) and no left atrial thrombus,

suggest attempting PMBC despite unfavorable valve morphology

• Medical management or high-risk mitral valve surgery are reasonable

alternatives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-240516103314-049e168c/85/1-MITRAL-STENOSIS-AND-ITS-MANAGEMENT-51-320.jpg)