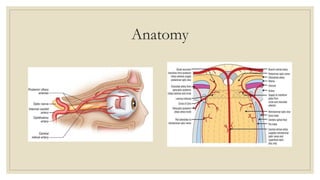

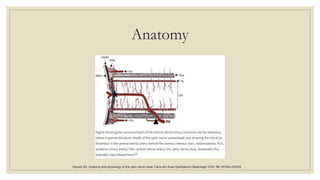

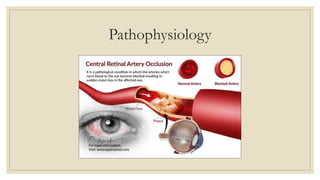

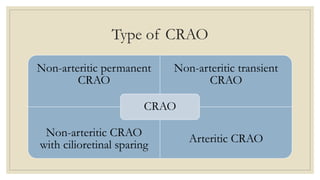

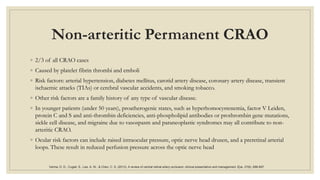

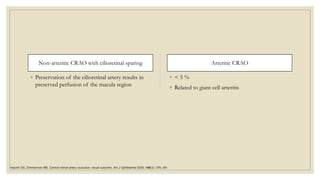

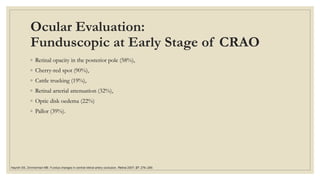

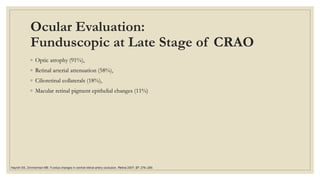

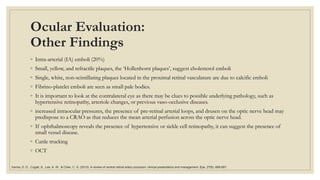

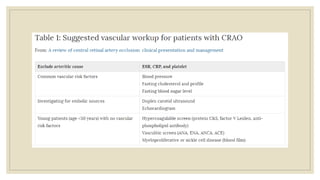

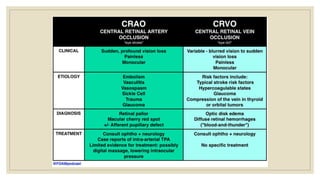

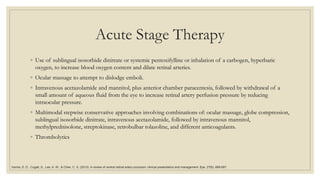

This document discusses central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), an ophthalmic emergency caused by obstruction of the central retinal artery. It affects around 1 in 100,000 people and often leads to severe vision loss. CRAO can be caused by emboli or thrombi and is associated with atherosclerosis and other vascular risk factors. The diagnosis involves examining the eye for signs like a cherry red spot at the macula. Acute management focuses on restoring retinal blood flow through measures like ocular massage or vasodilators. Long term management aims to prevent further vascular events through treating underlying risk factors.