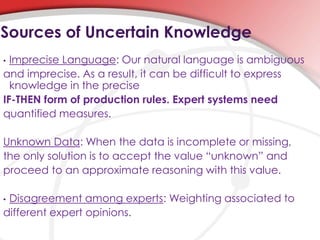

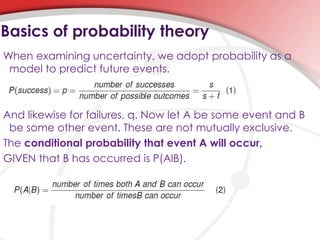

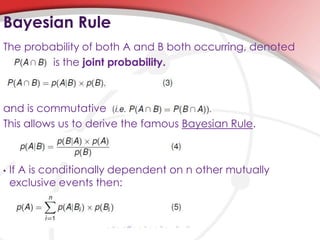

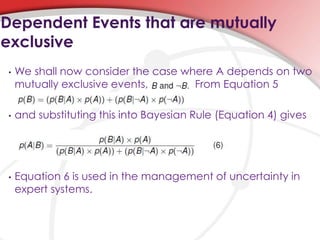

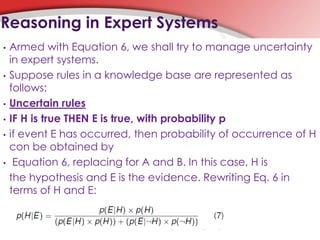

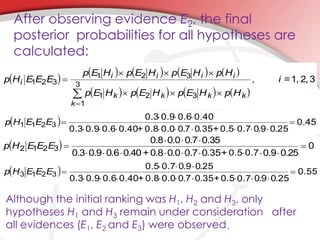

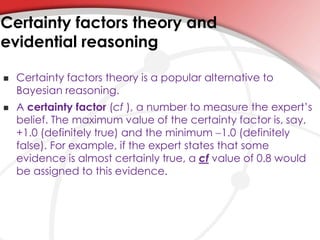

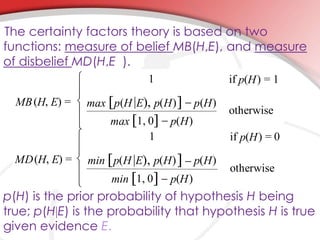

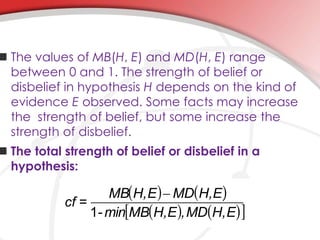

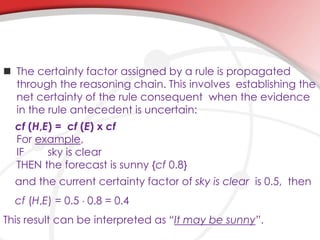

This document outlines techniques for representing uncertainty in expert systems, including Bayesian reasoning and certainty factors theory. It discusses sources of uncertain knowledge, probabilistic reasoning using Bayes' rule, and an example of computing posterior probabilities of hypotheses given observed evidence. Certainty factors theory is presented as an alternative to Bayesian reasoning that uses numerical factors between -1 and 1 to represent degrees of belief.