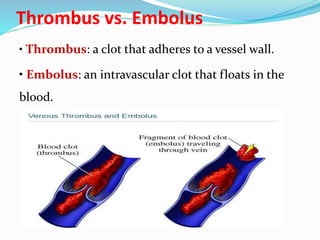

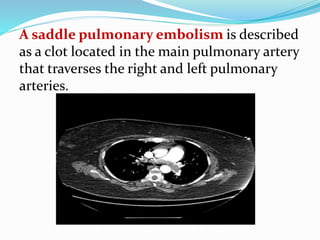

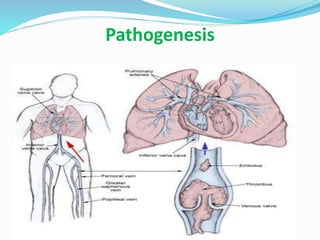

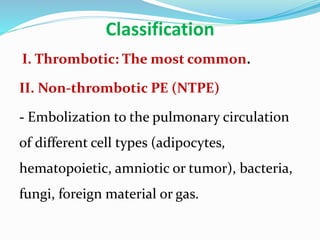

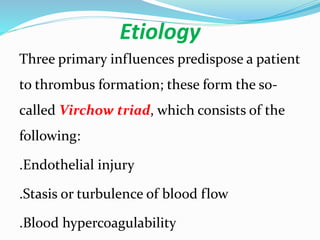

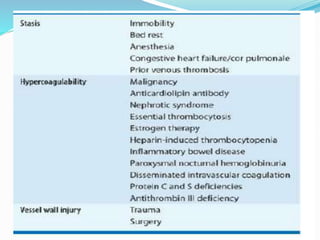

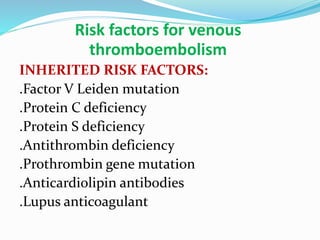

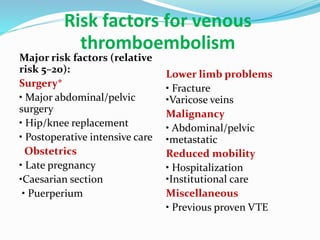

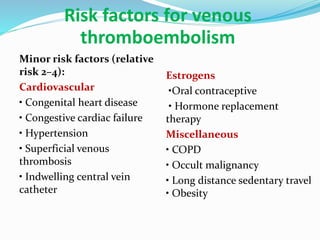

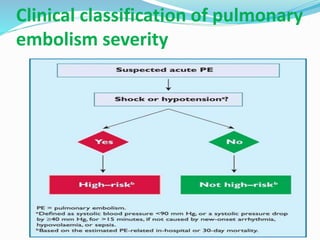

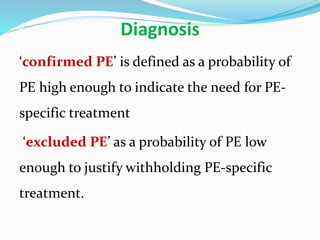

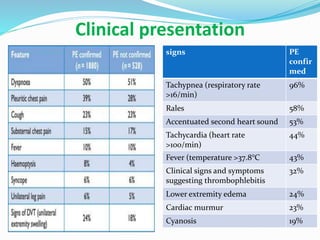

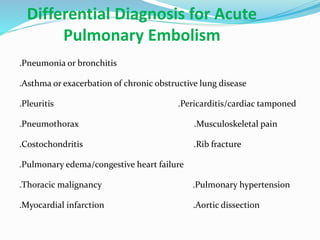

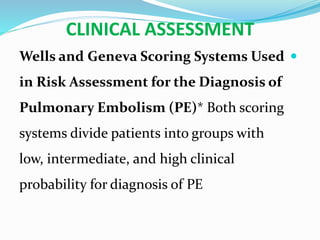

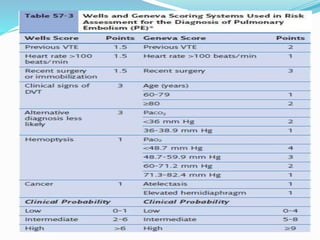

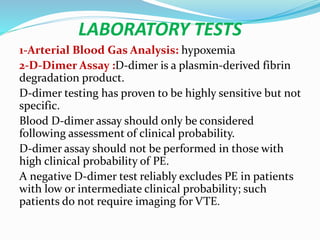

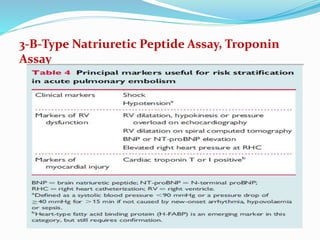

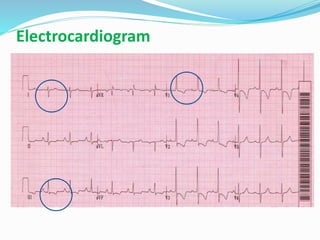

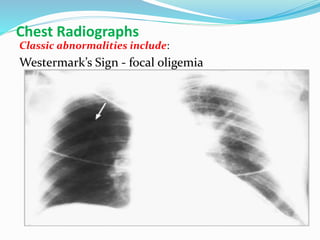

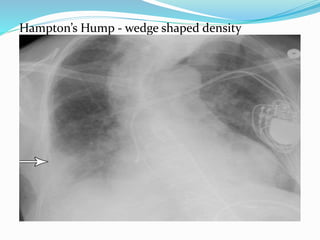

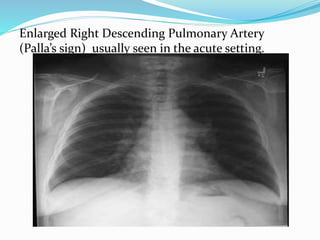

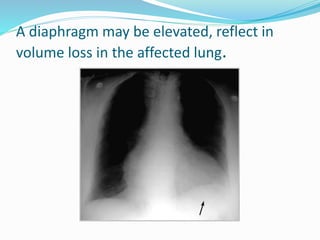

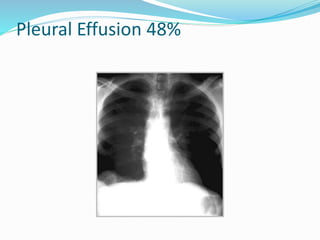

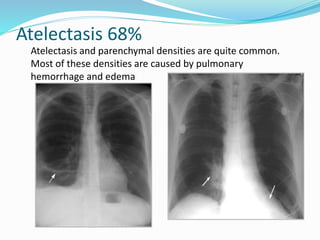

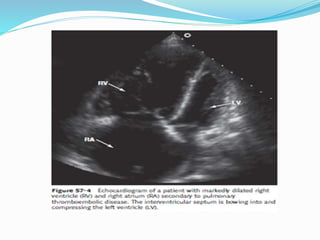

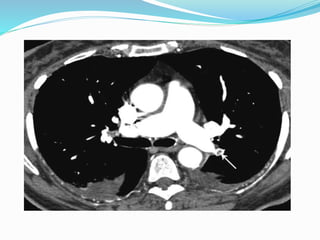

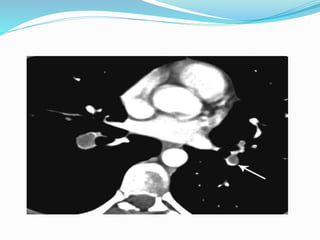

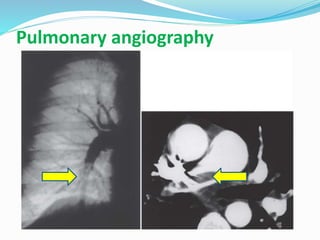

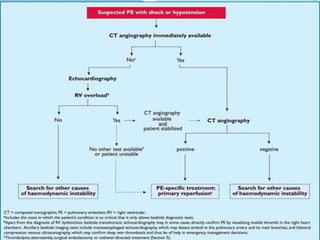

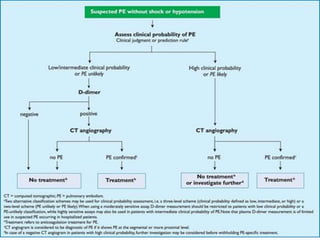

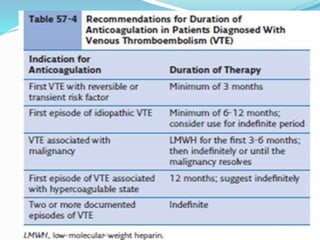

This document discusses hemostasis, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of venous thromboembolism. It defines key terms like thrombus, embolus, and saddle pulmonary embolism. Diagnostic tests covered include D-dimer, ventilation-perfusion scan, and CTA. Treatment involves anticoagulants like heparin, LMWH, factor Xa inhibitors, and thrombolytic therapy. Long-term management uses warfarin or novel oral anticoagulants. Prophylaxis is also discussed.