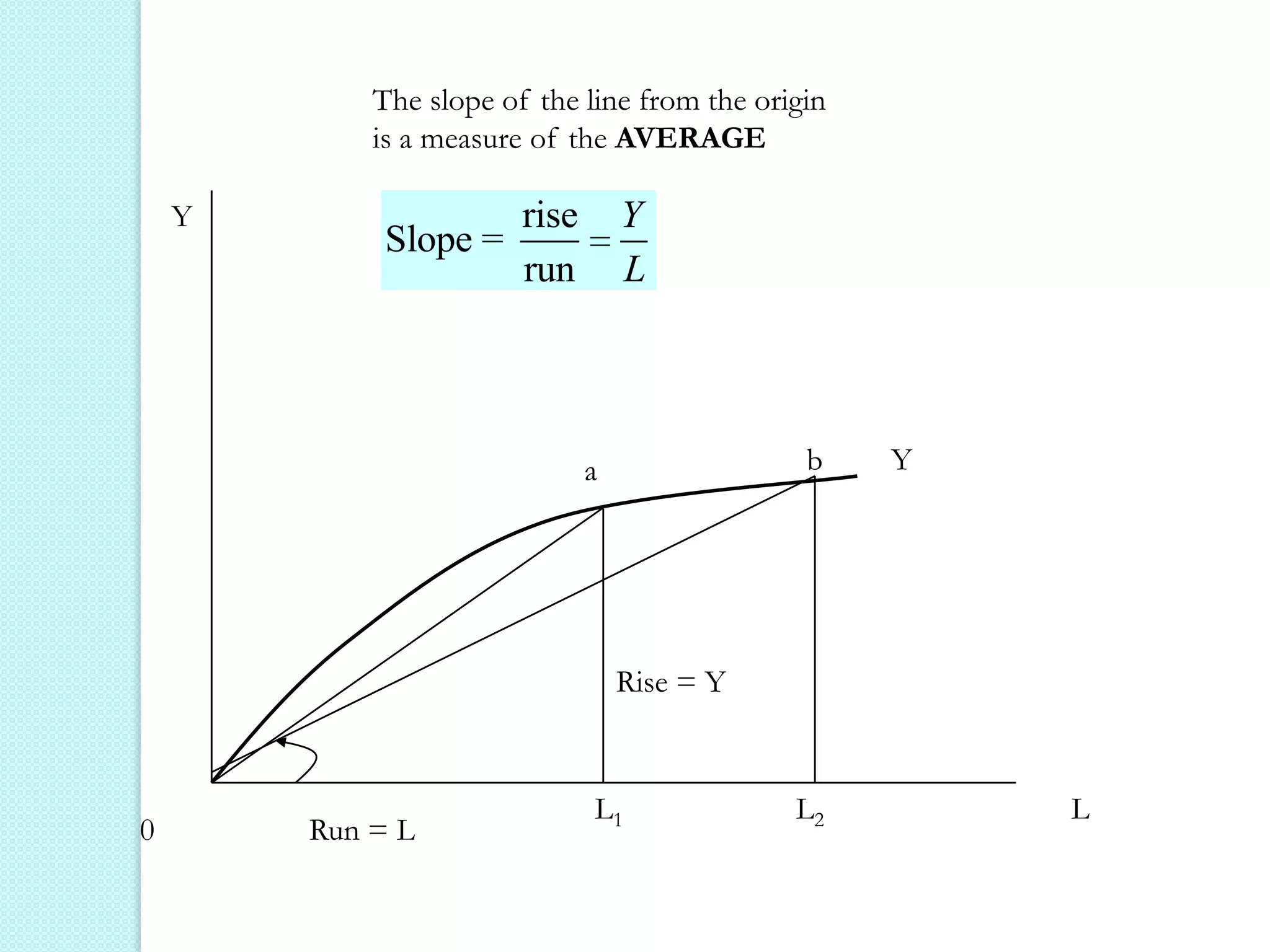

This document discusses production analysis and the theory of production costs from the perspective of a firm. It covers key concepts such as:

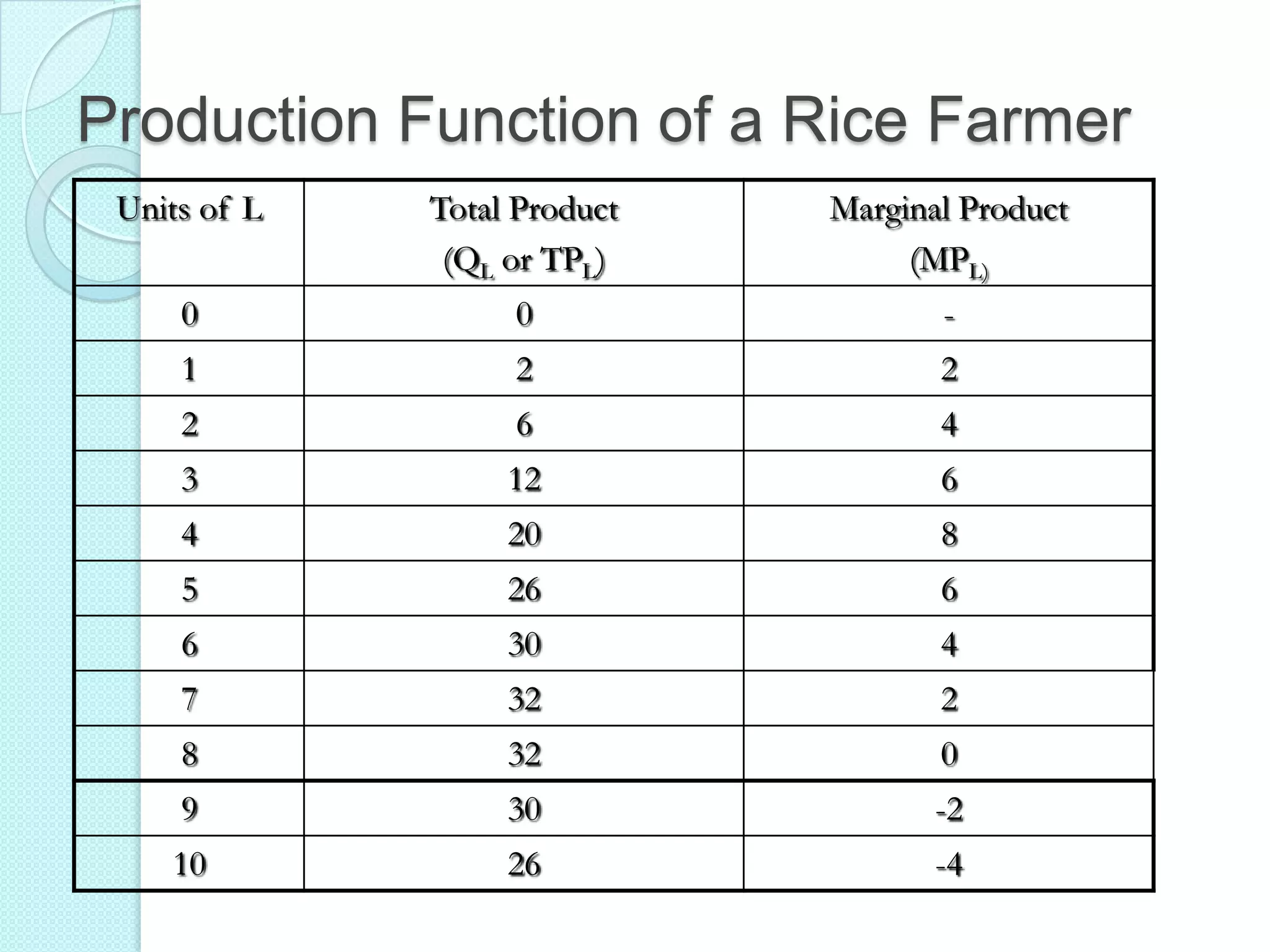

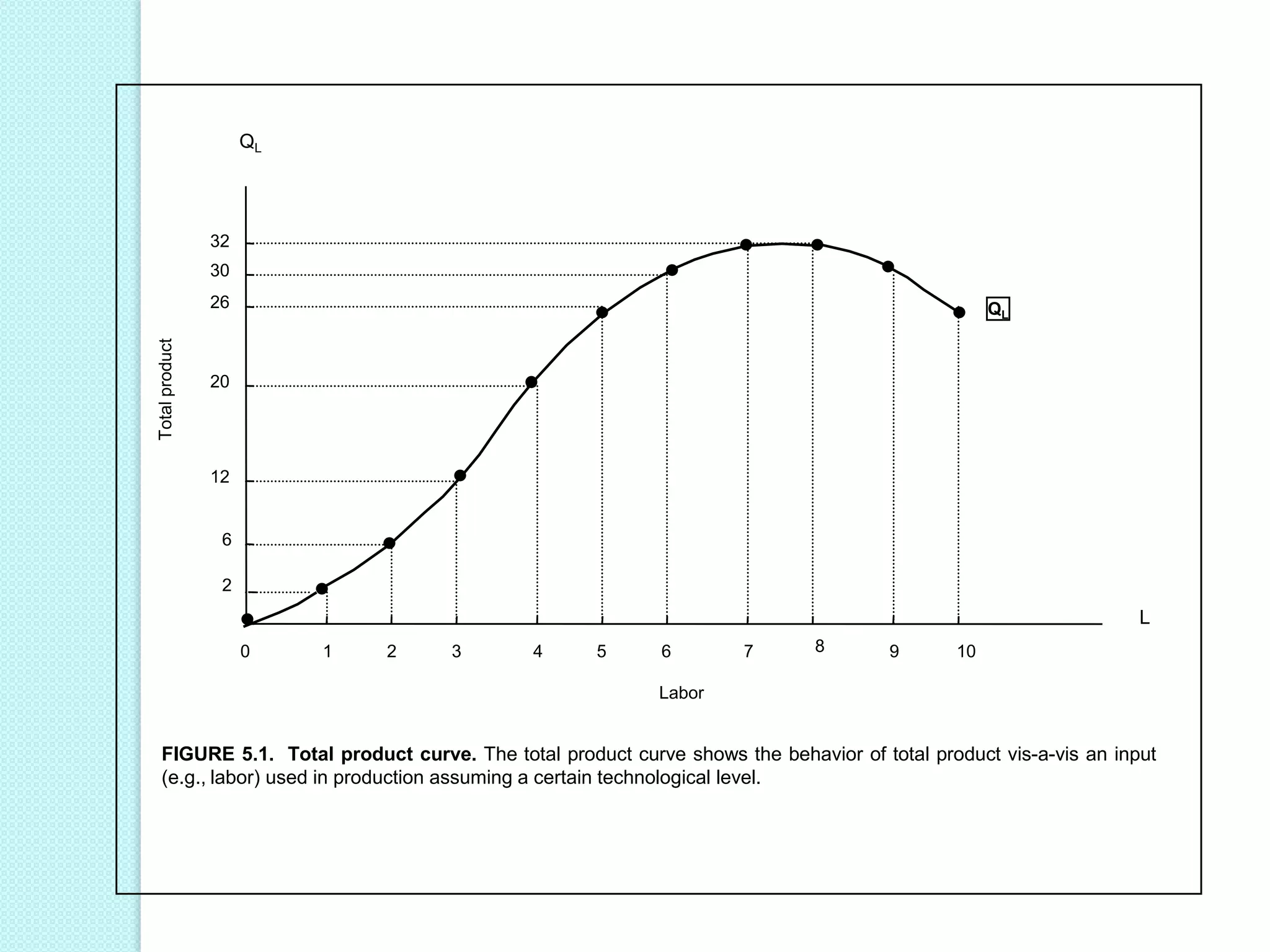

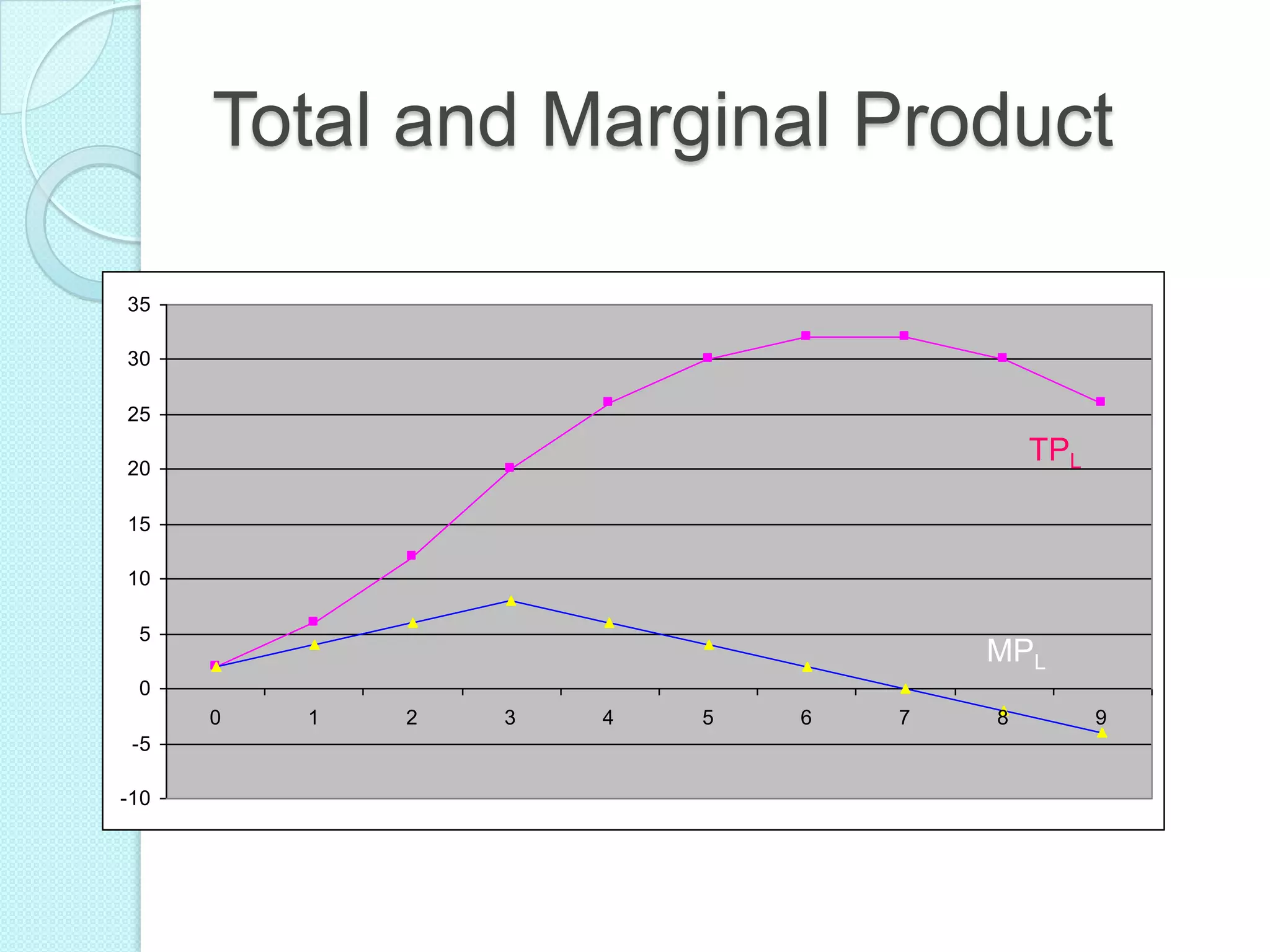

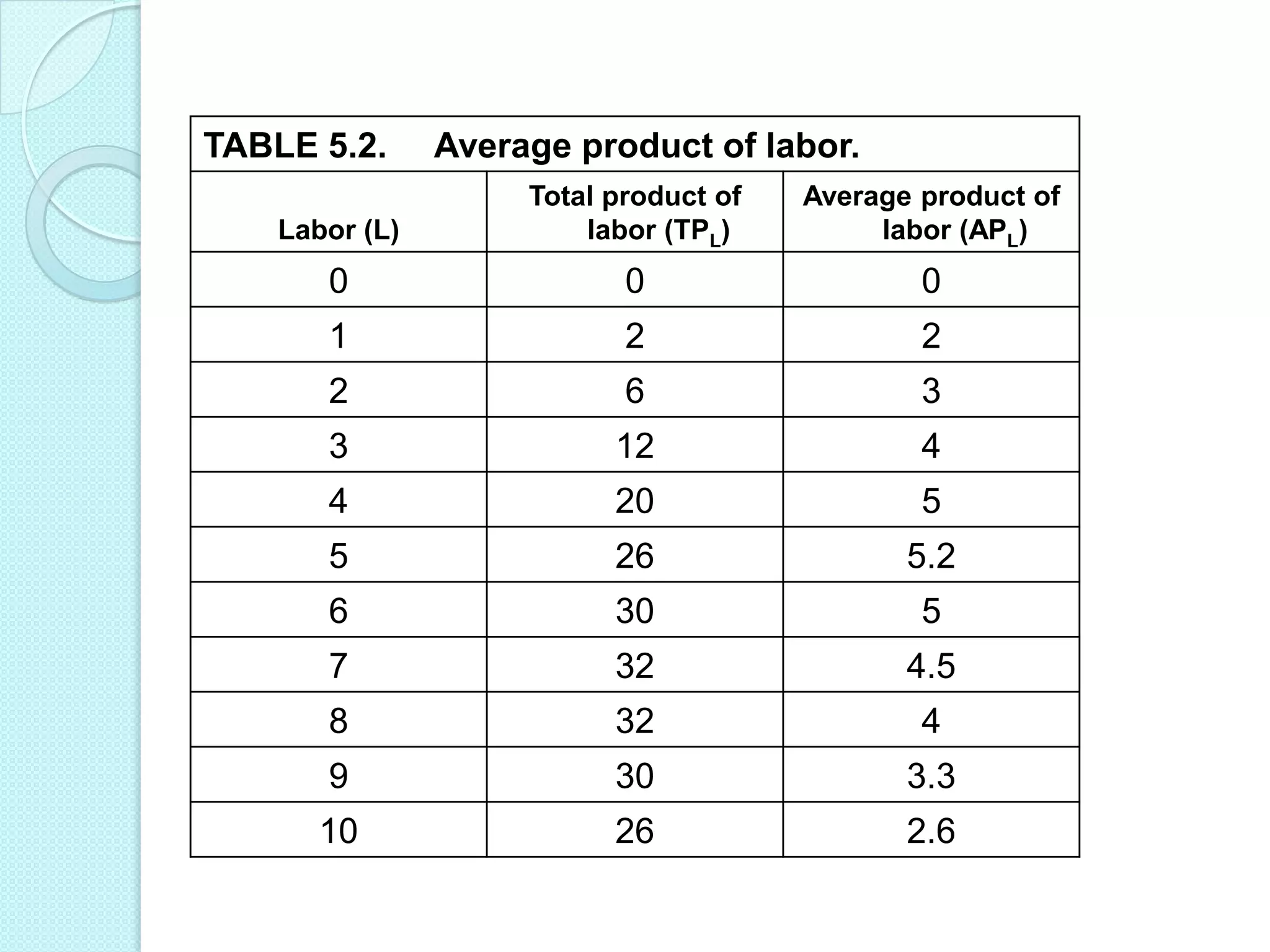

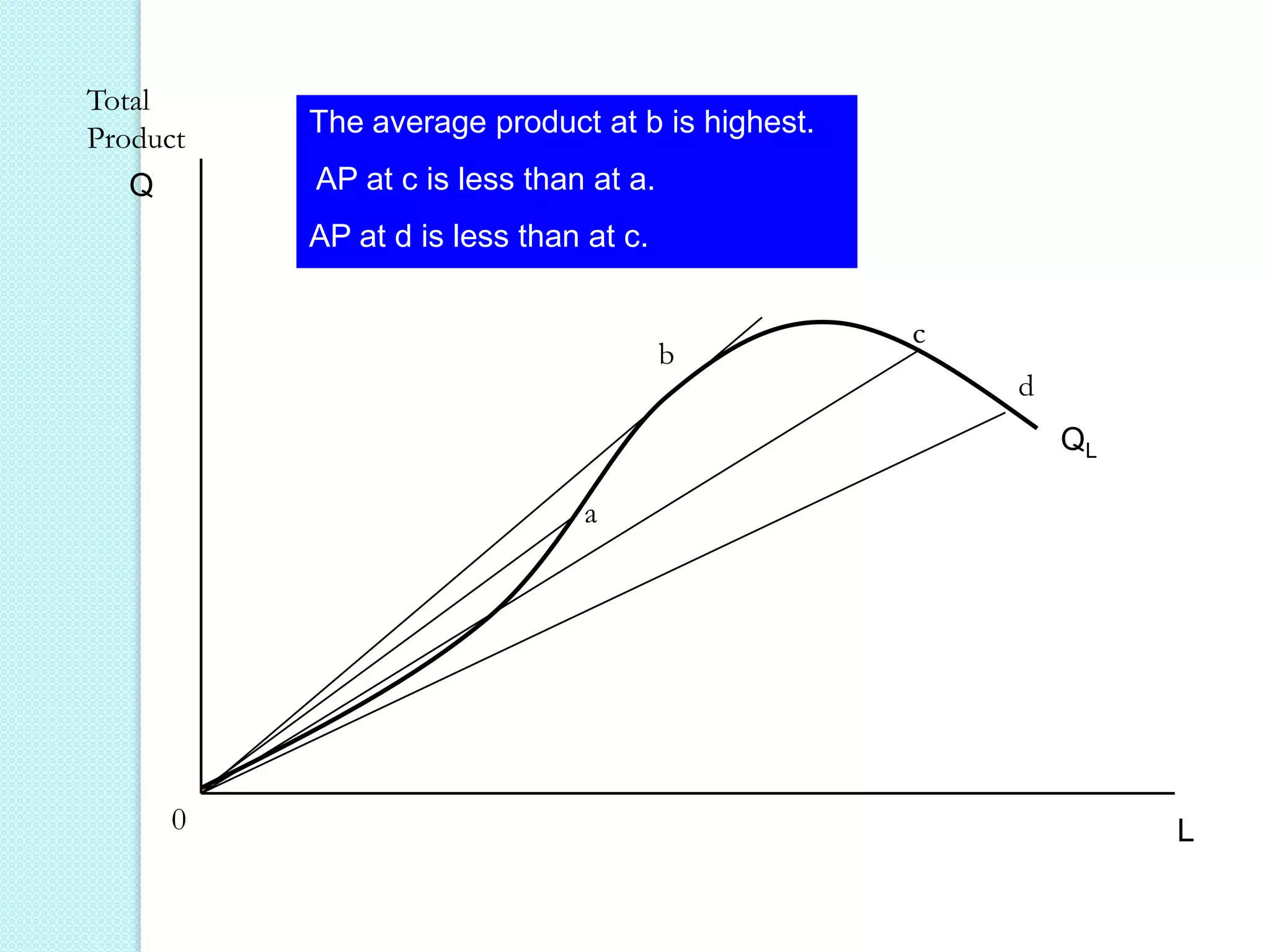

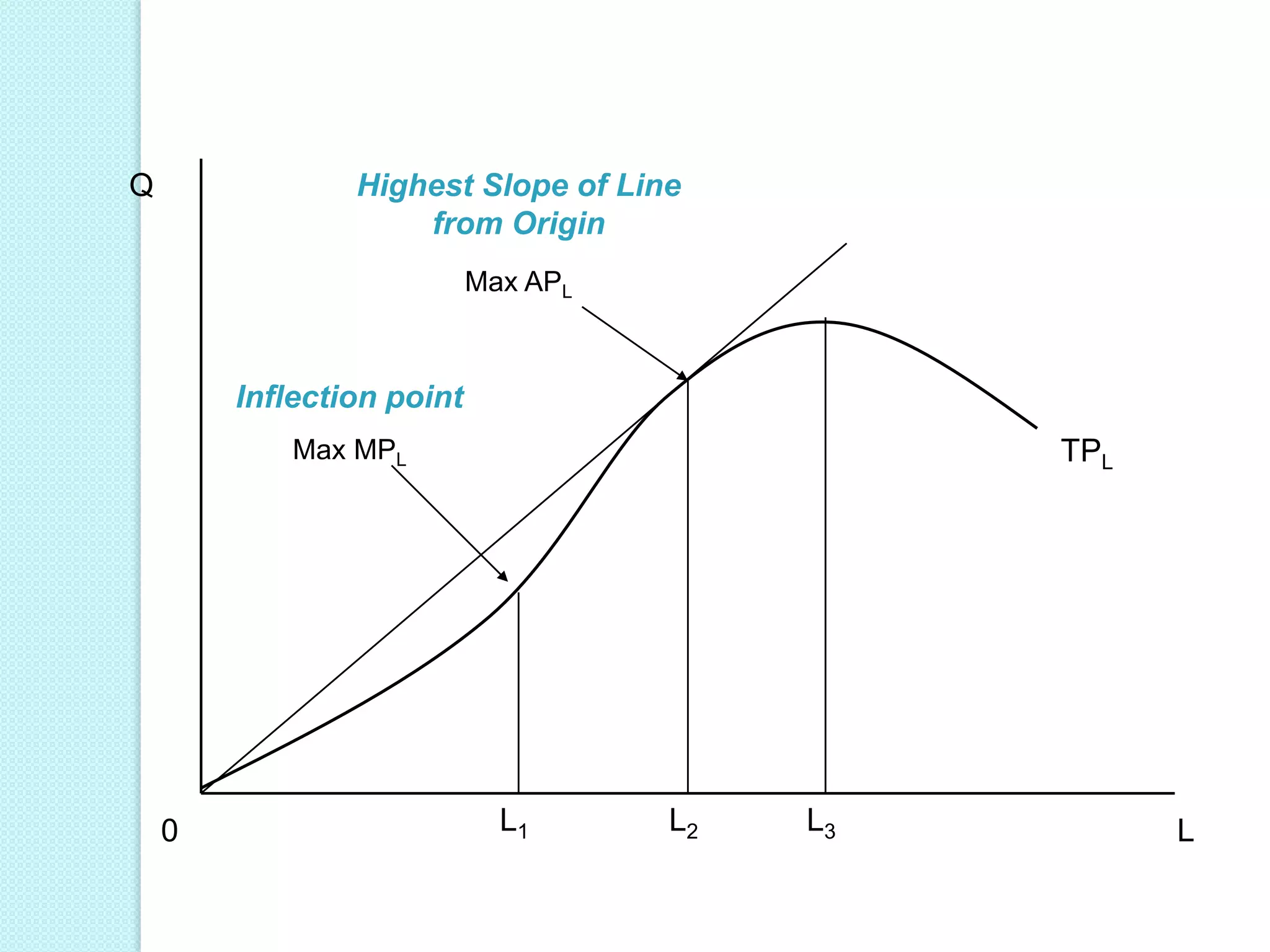

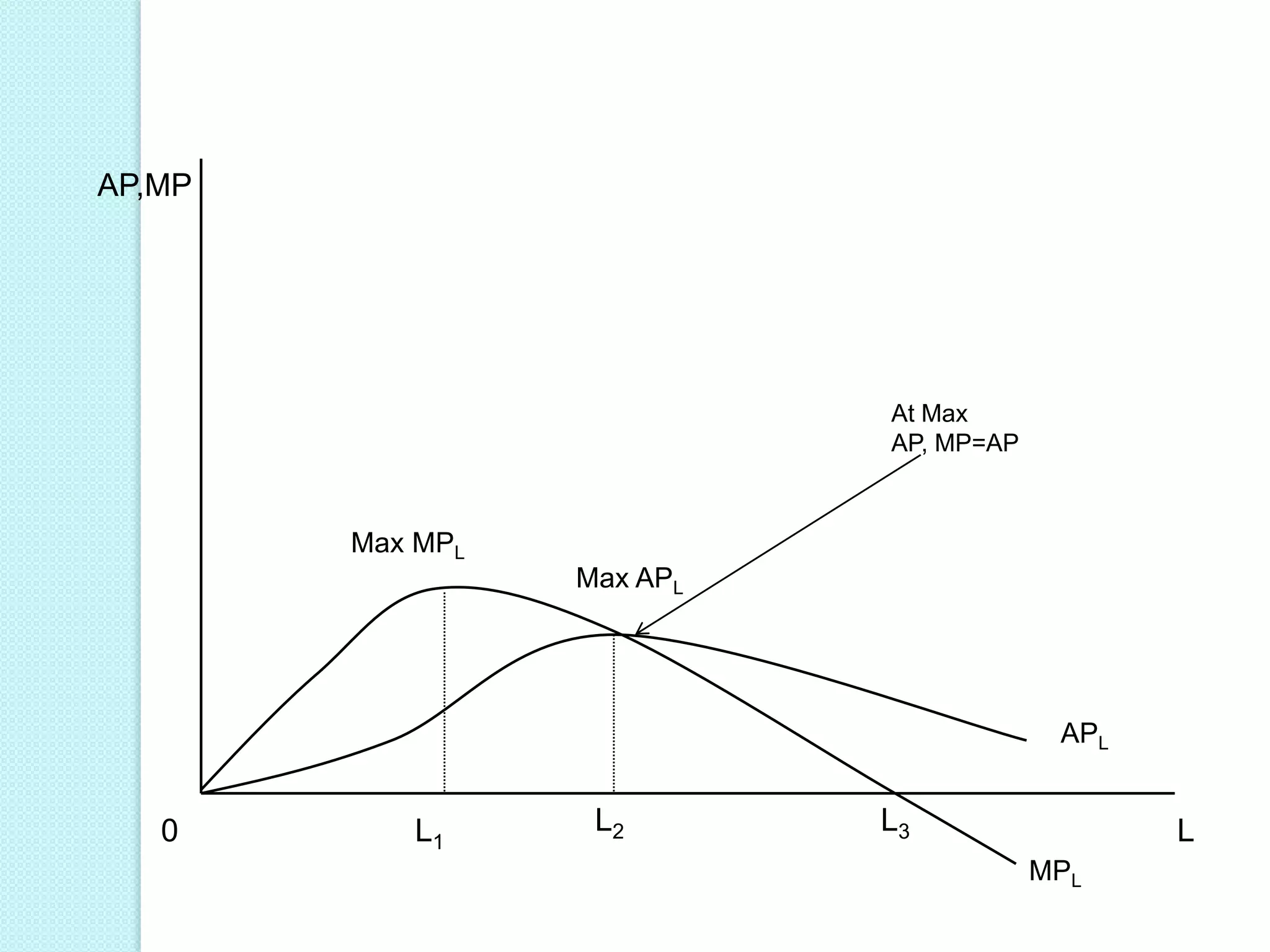

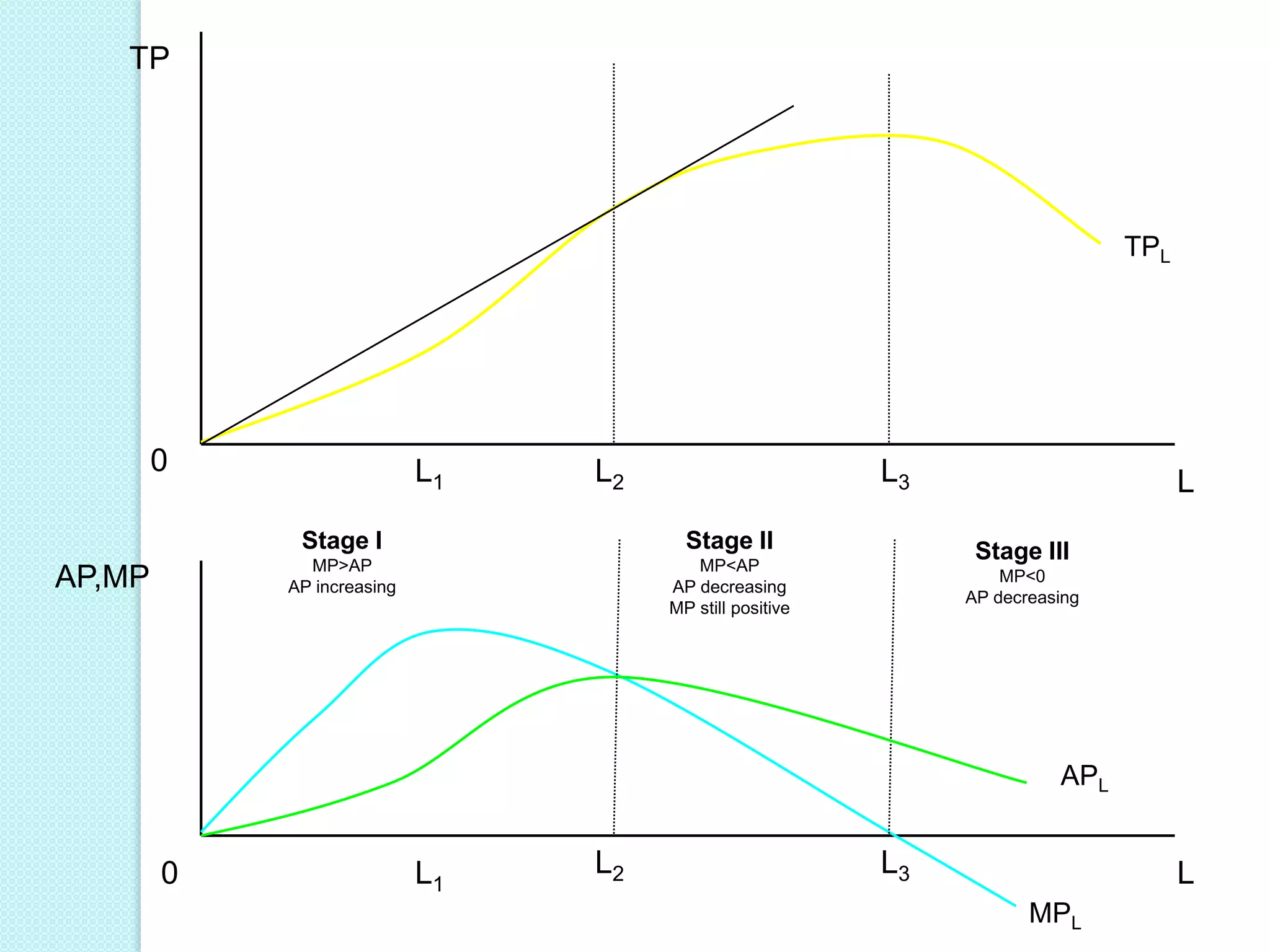

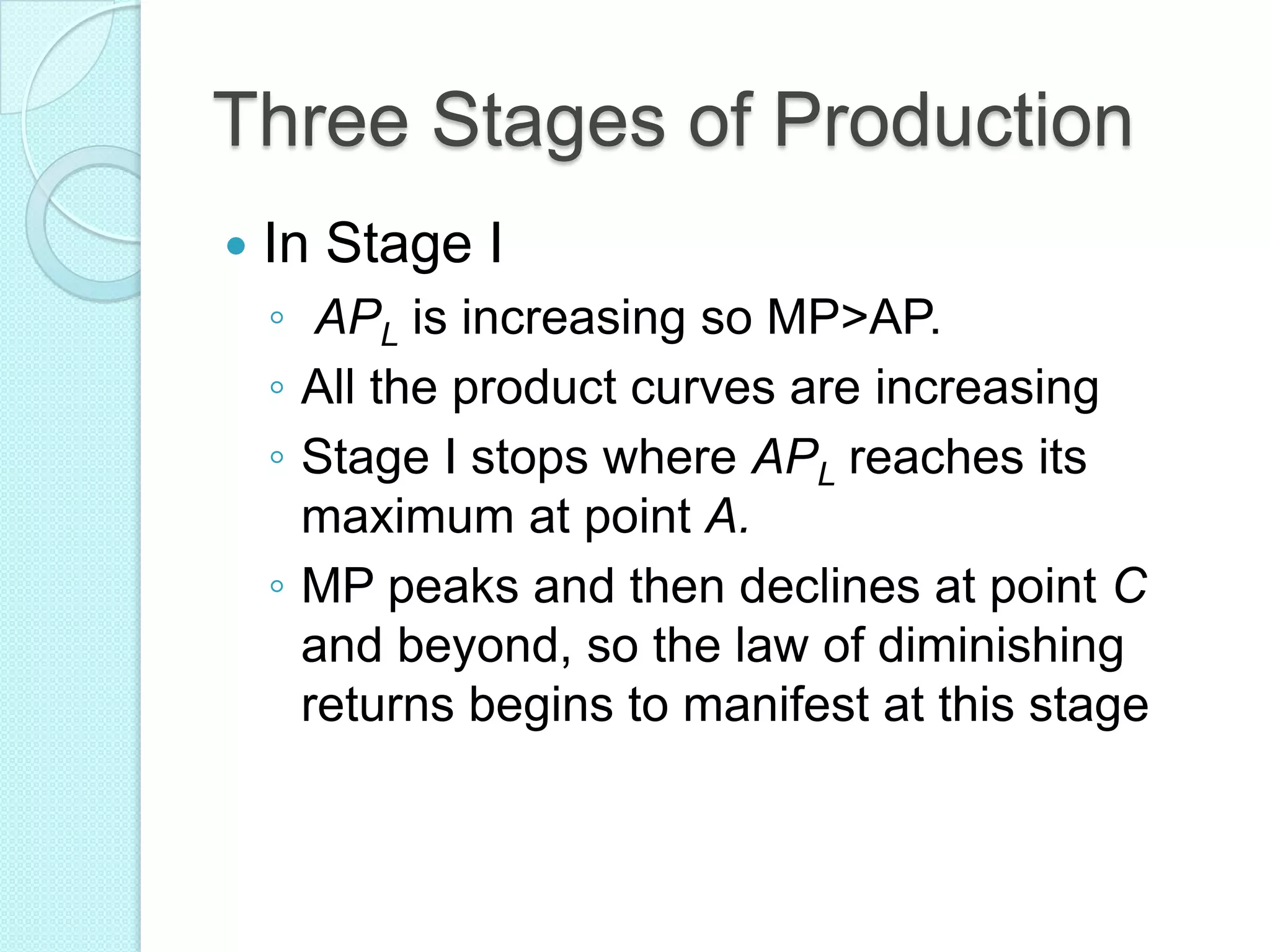

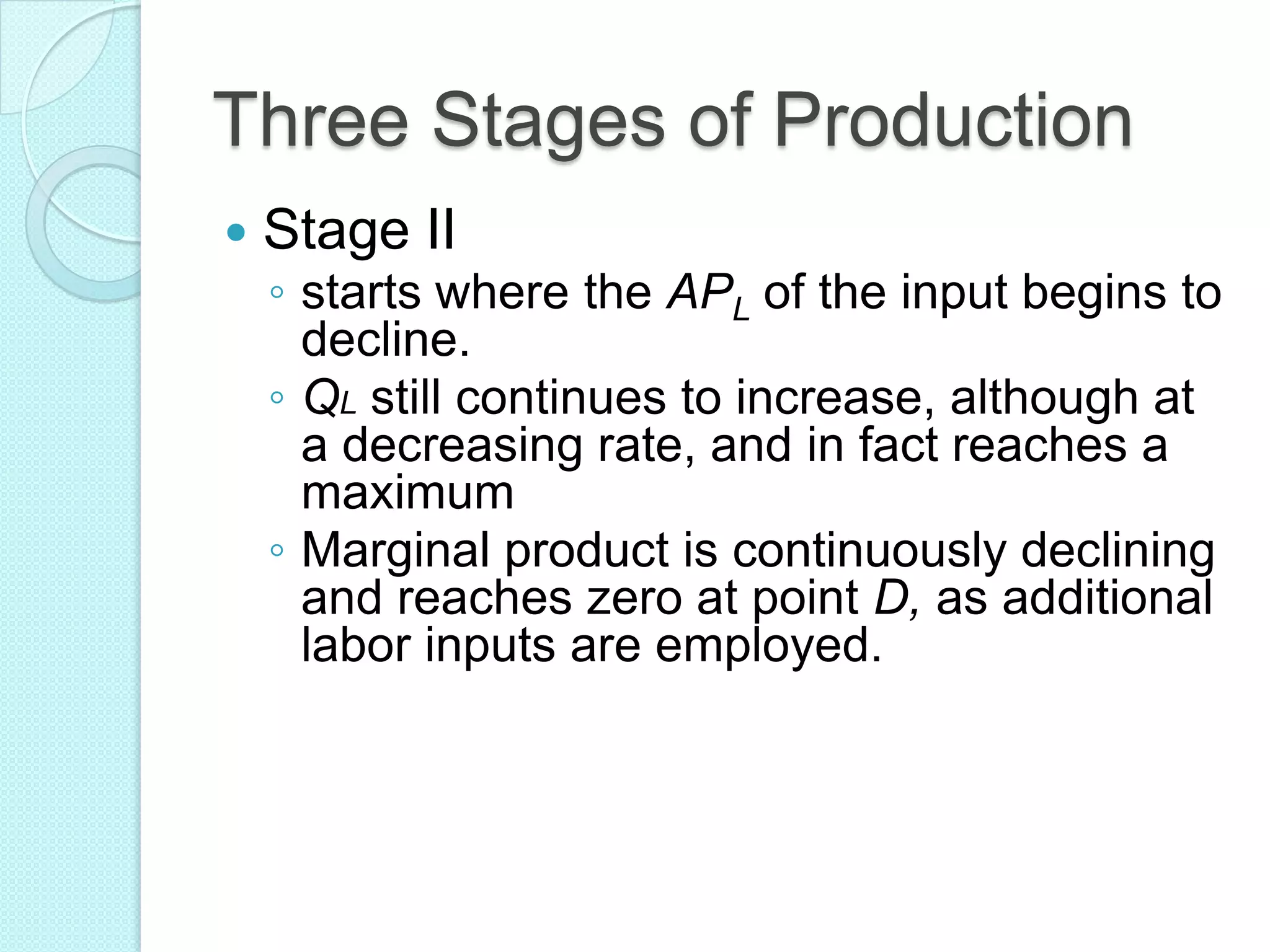

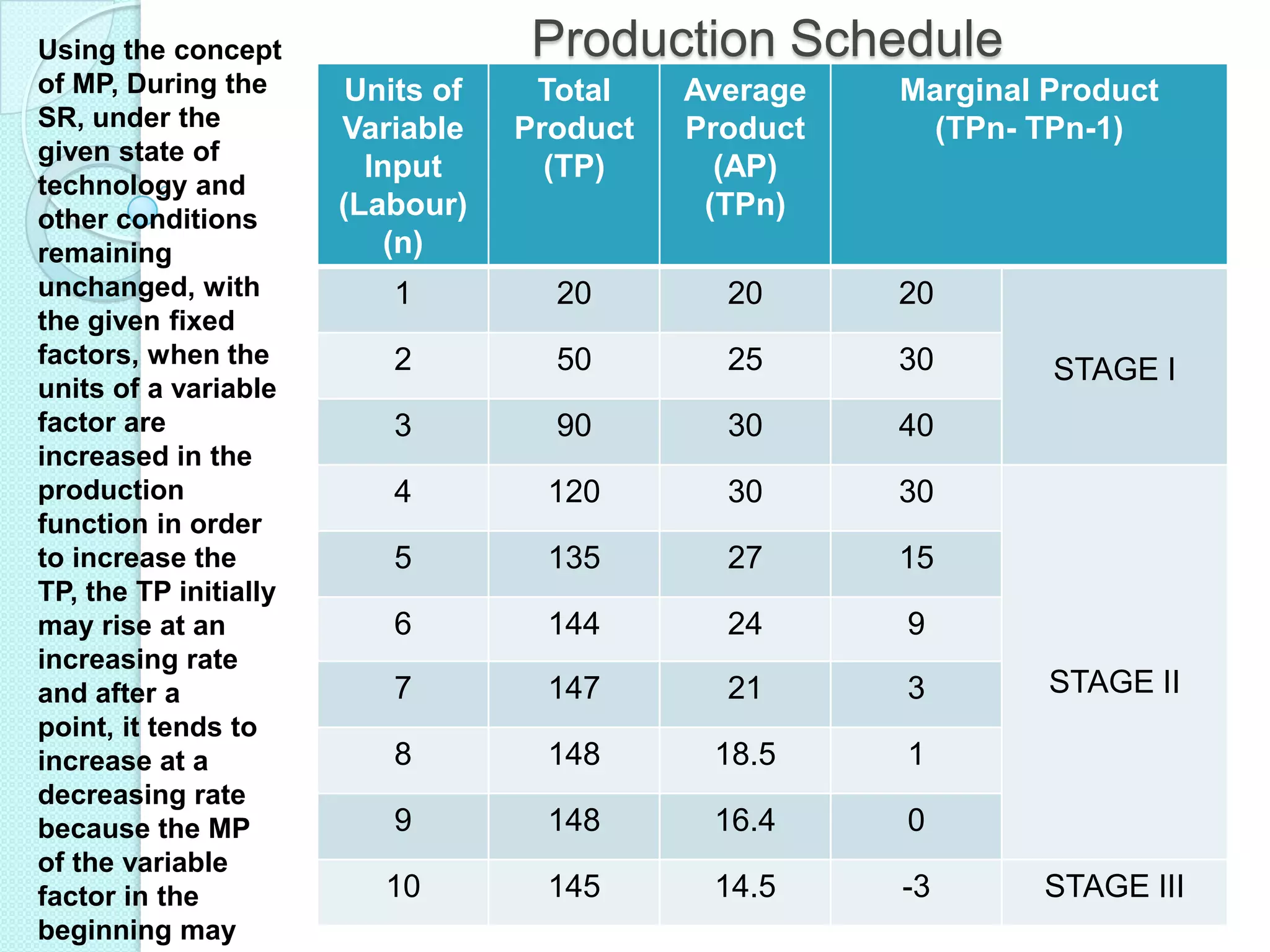

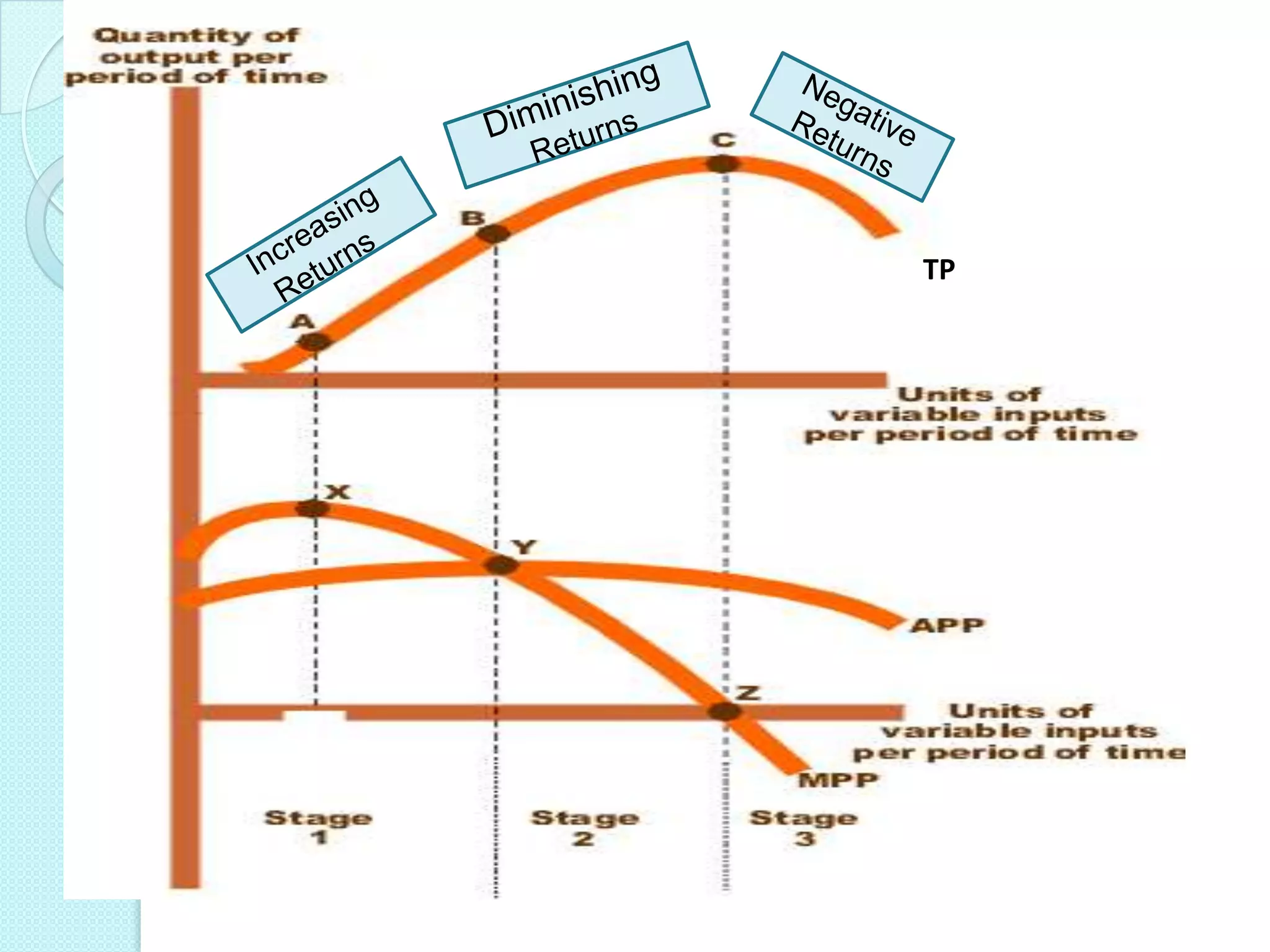

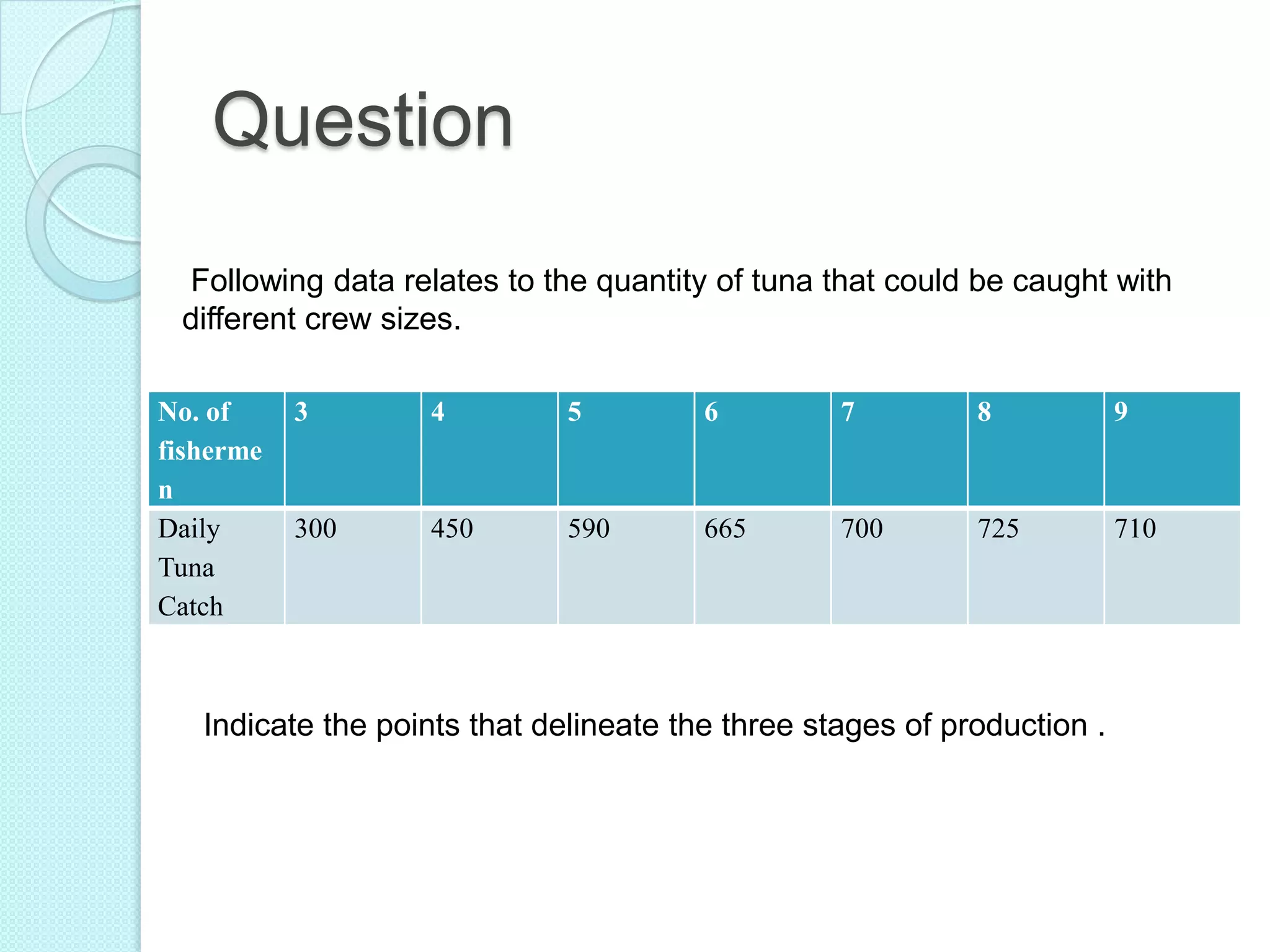

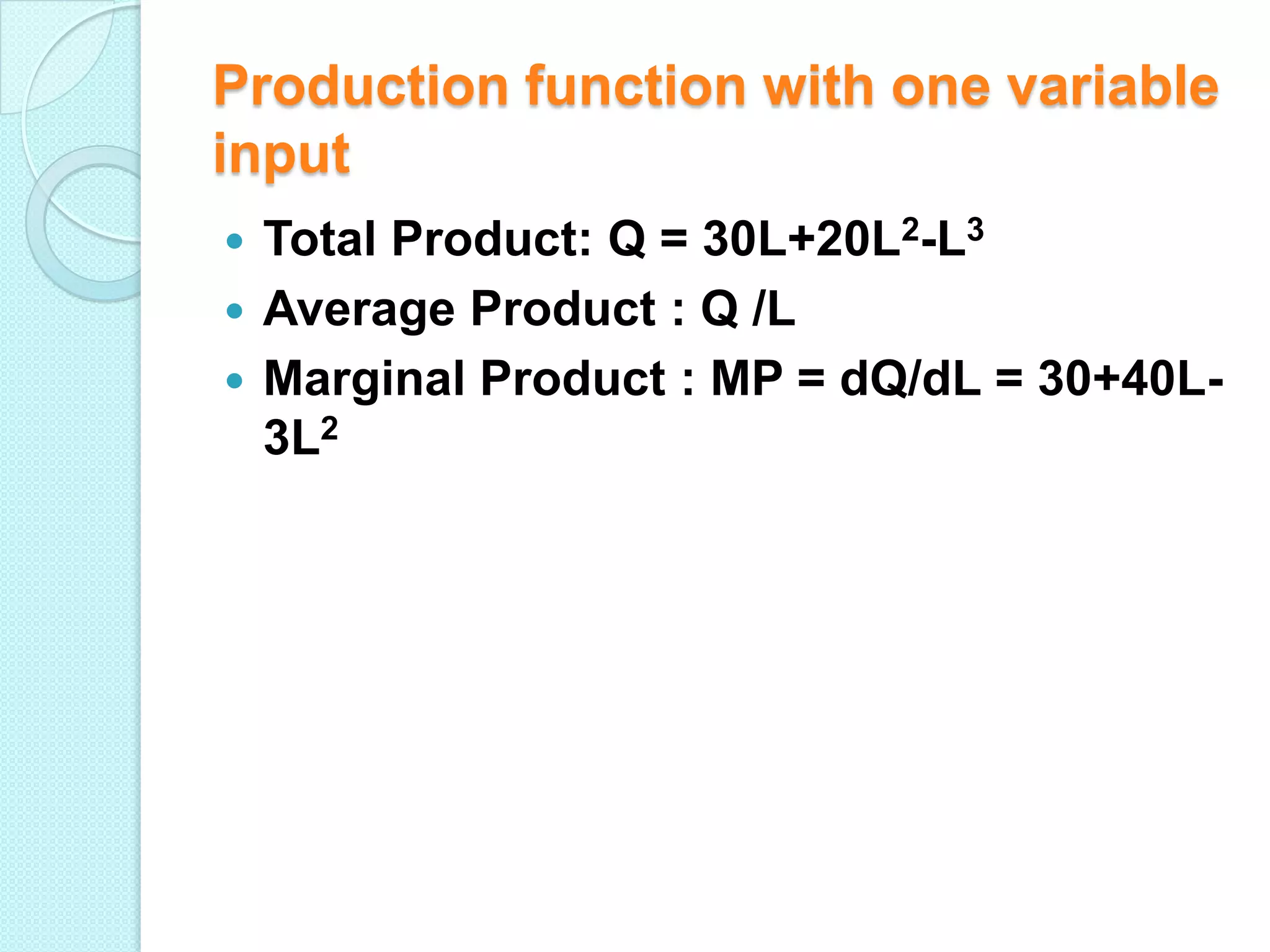

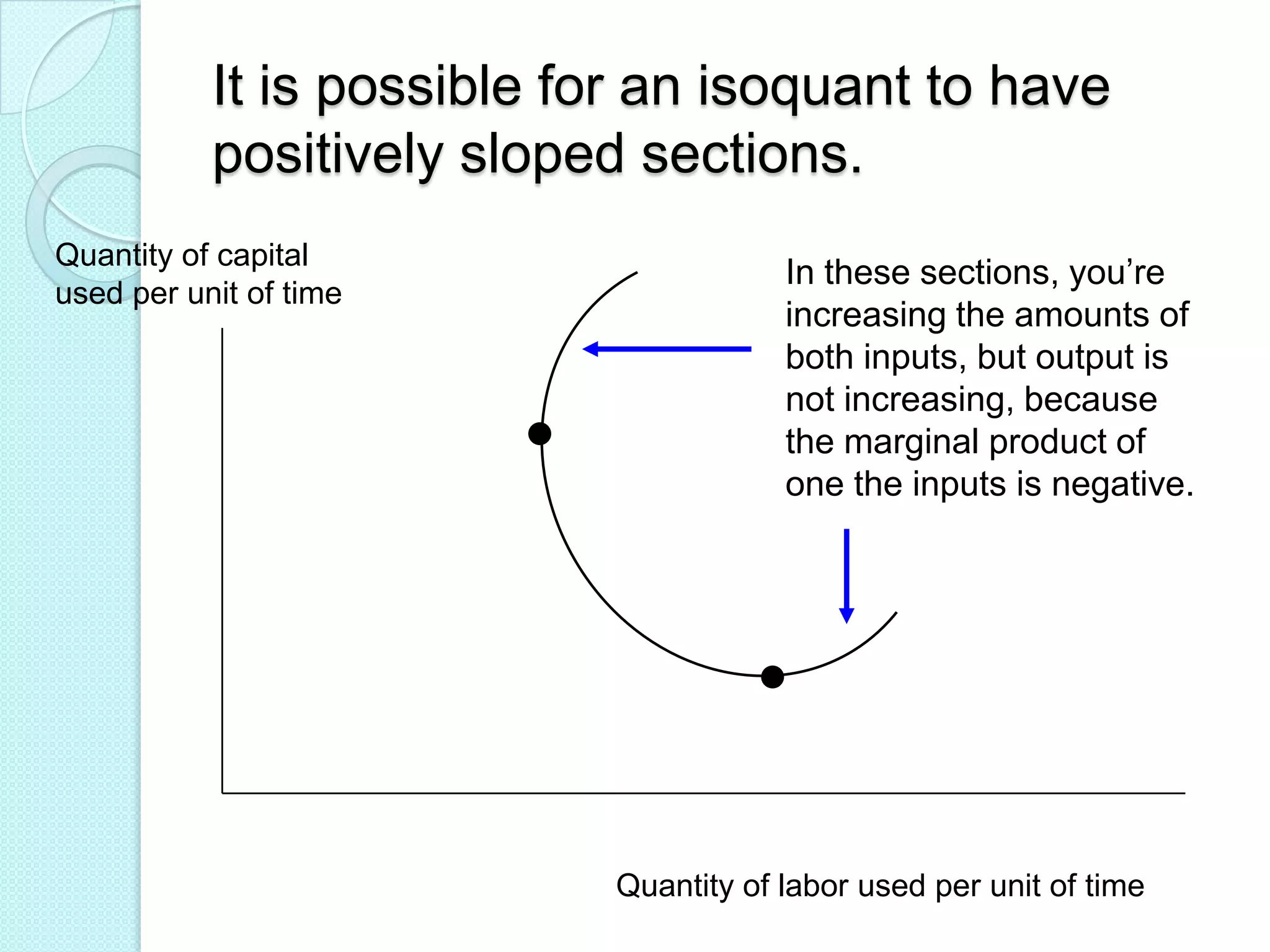

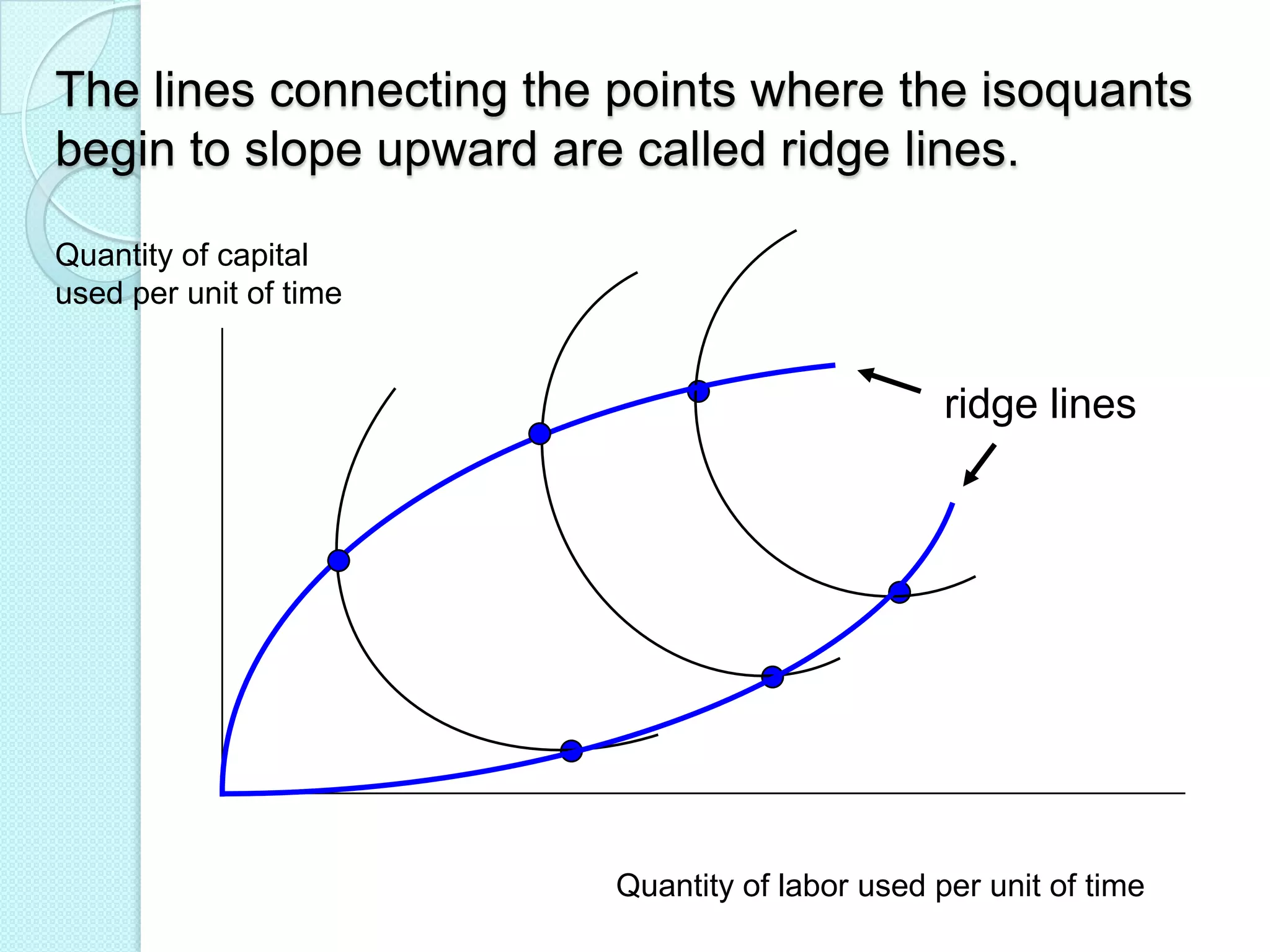

- The three stages of production as defined by total, average, and marginal product curves. In stage one, average product is increasing. In stage two, average product is decreasing while marginal product turns negative in stage three.

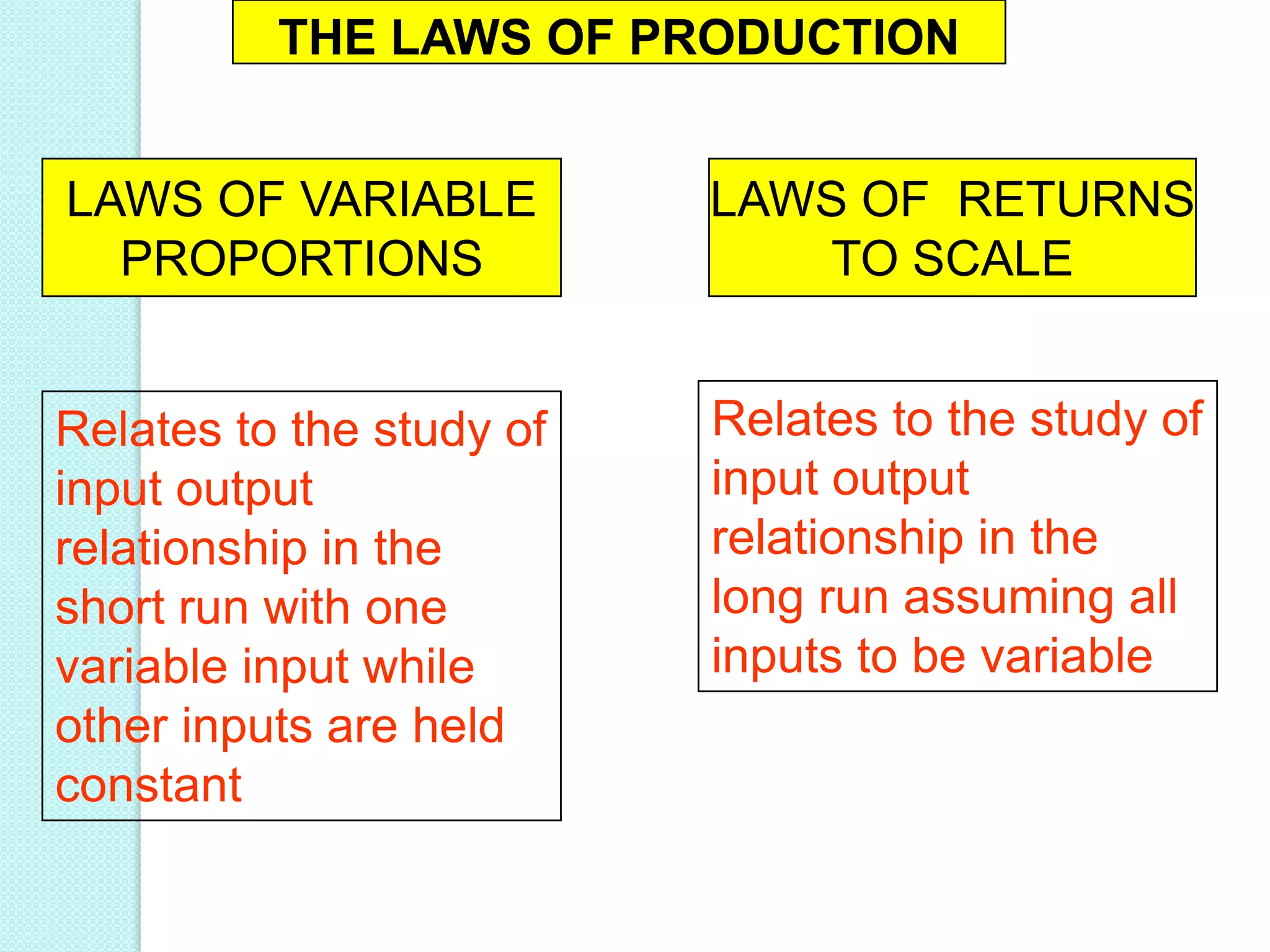

- Laws of variable proportions which state that as a variable input increases, total product initially increases at an increasing rate, then at a decreasing rate, due to diminishing marginal returns.

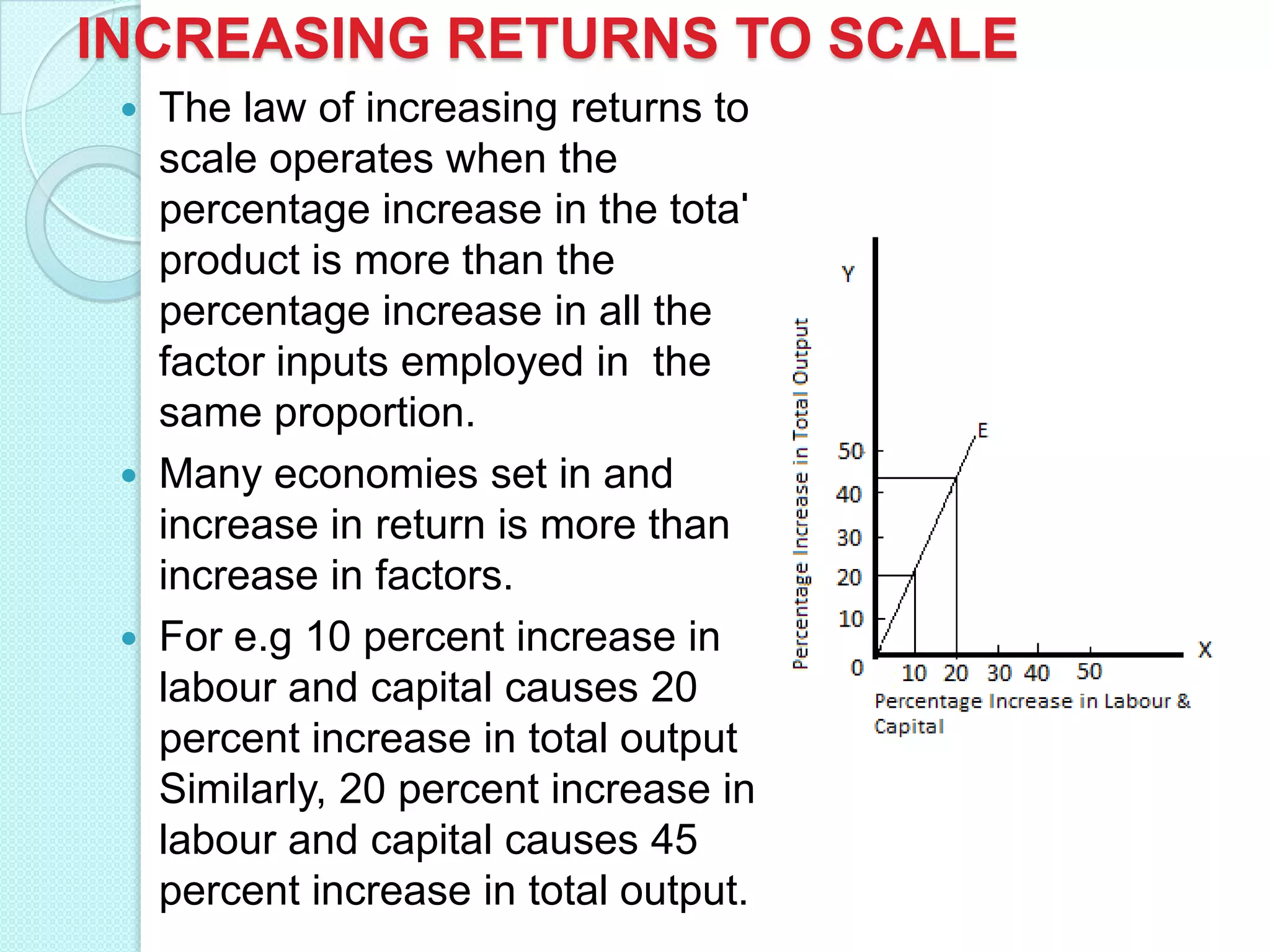

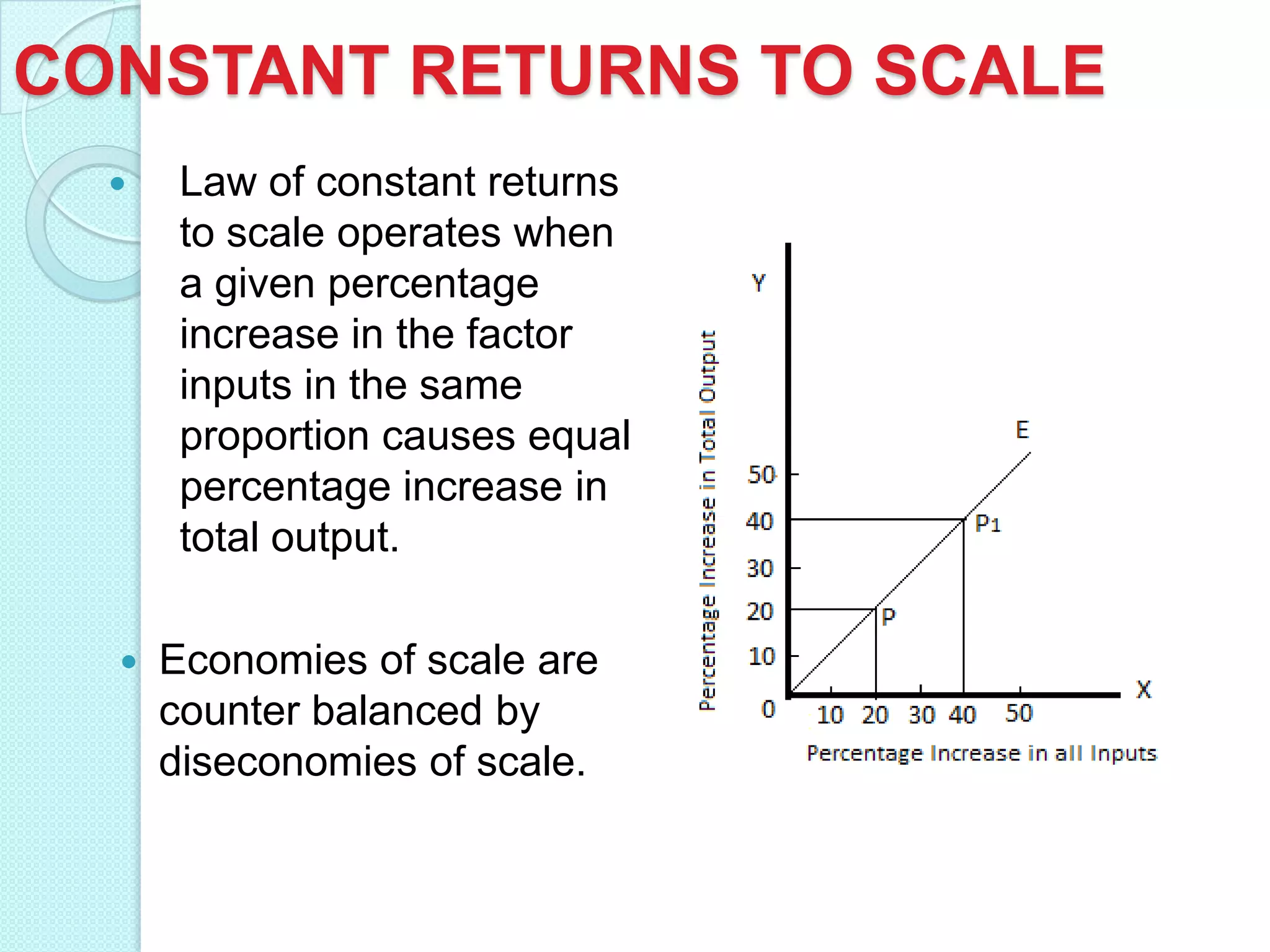

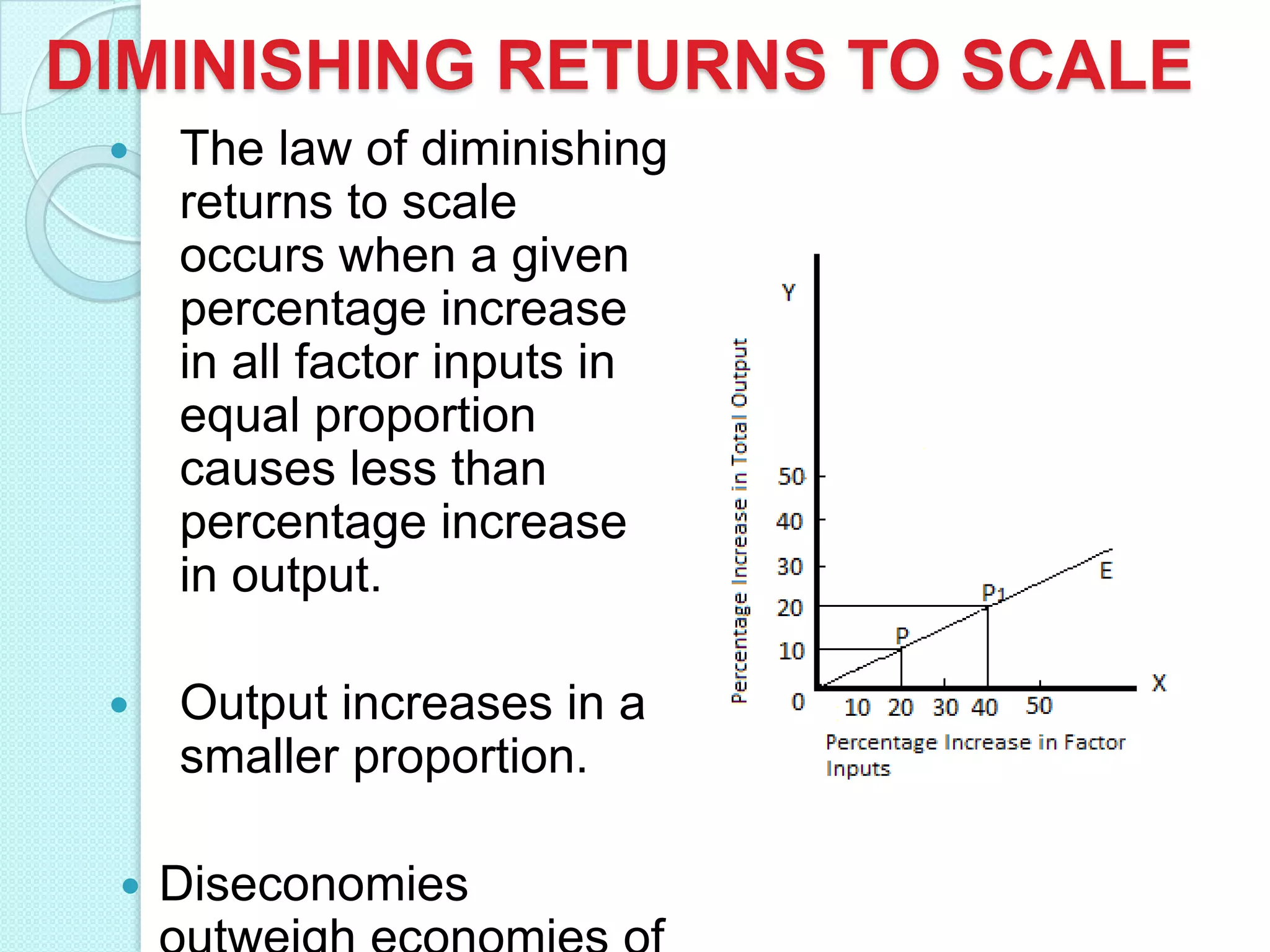

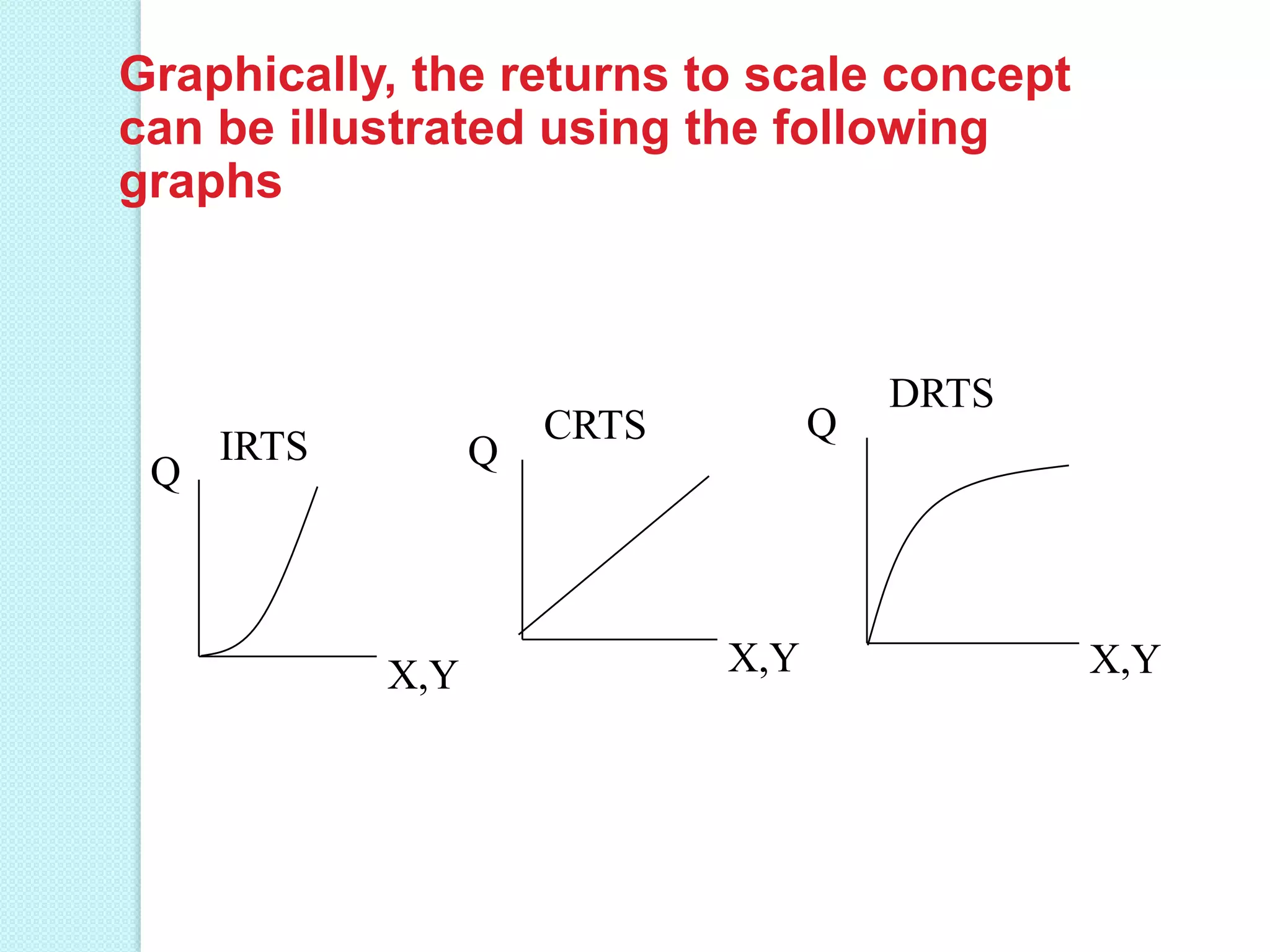

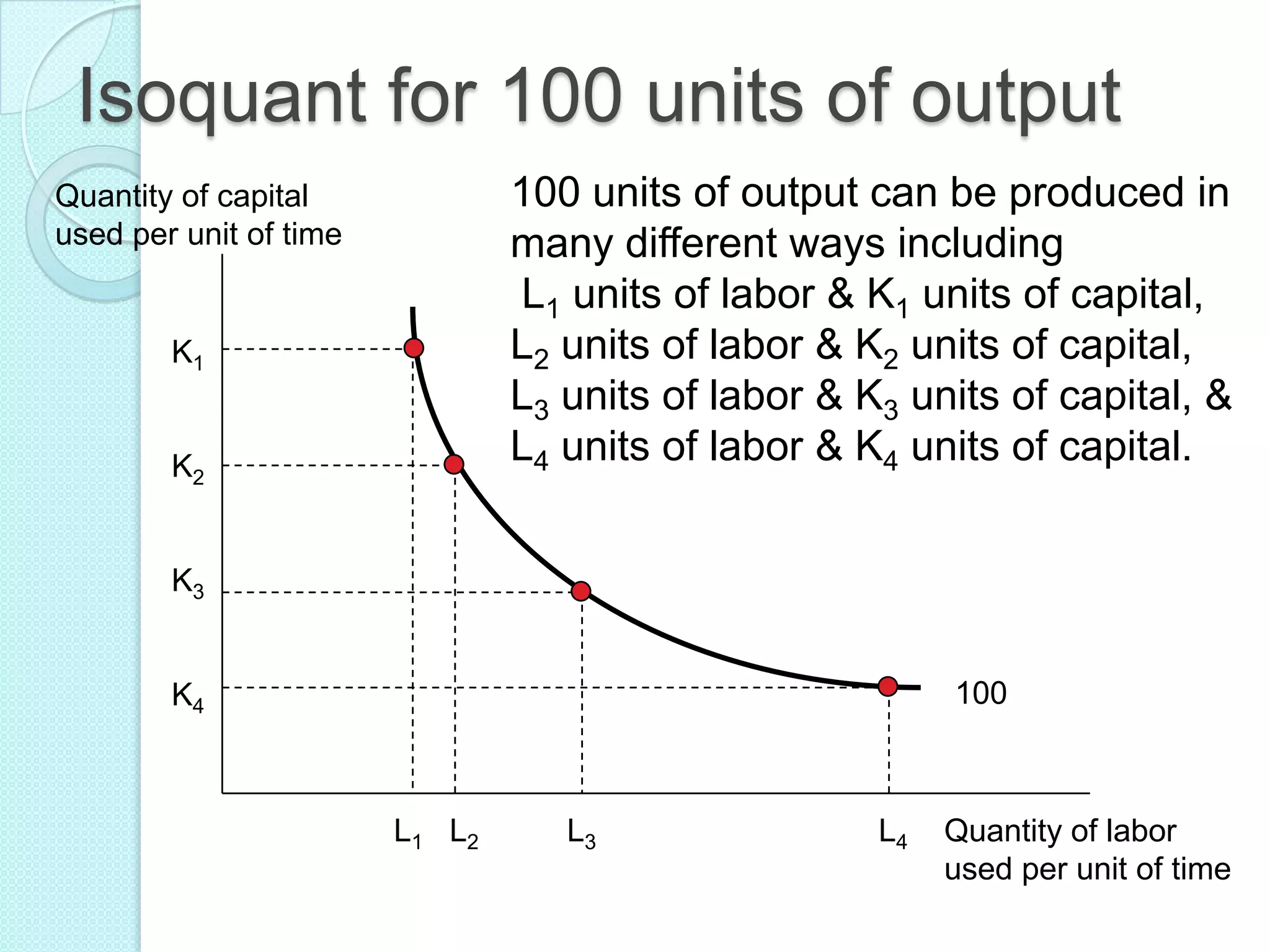

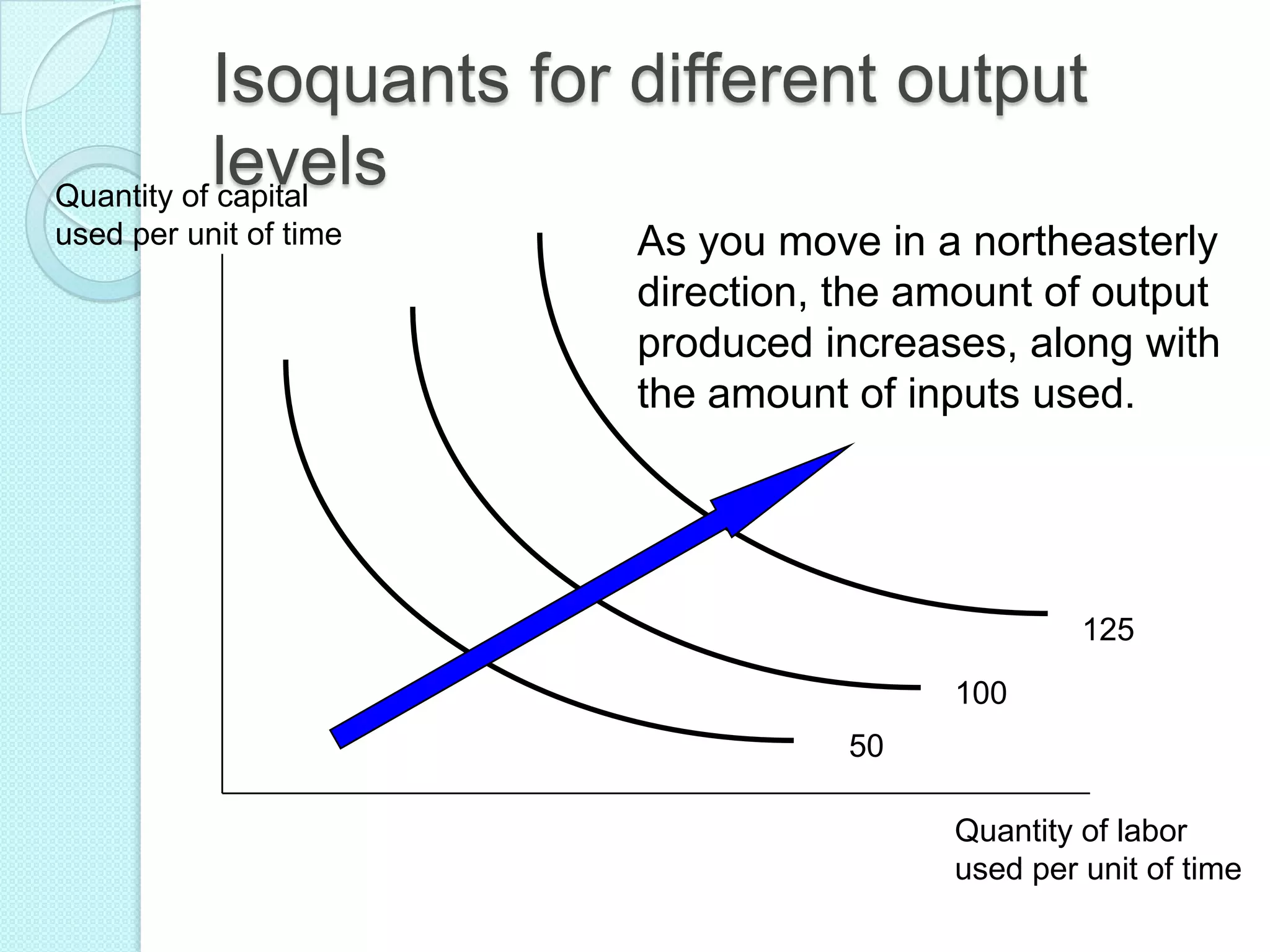

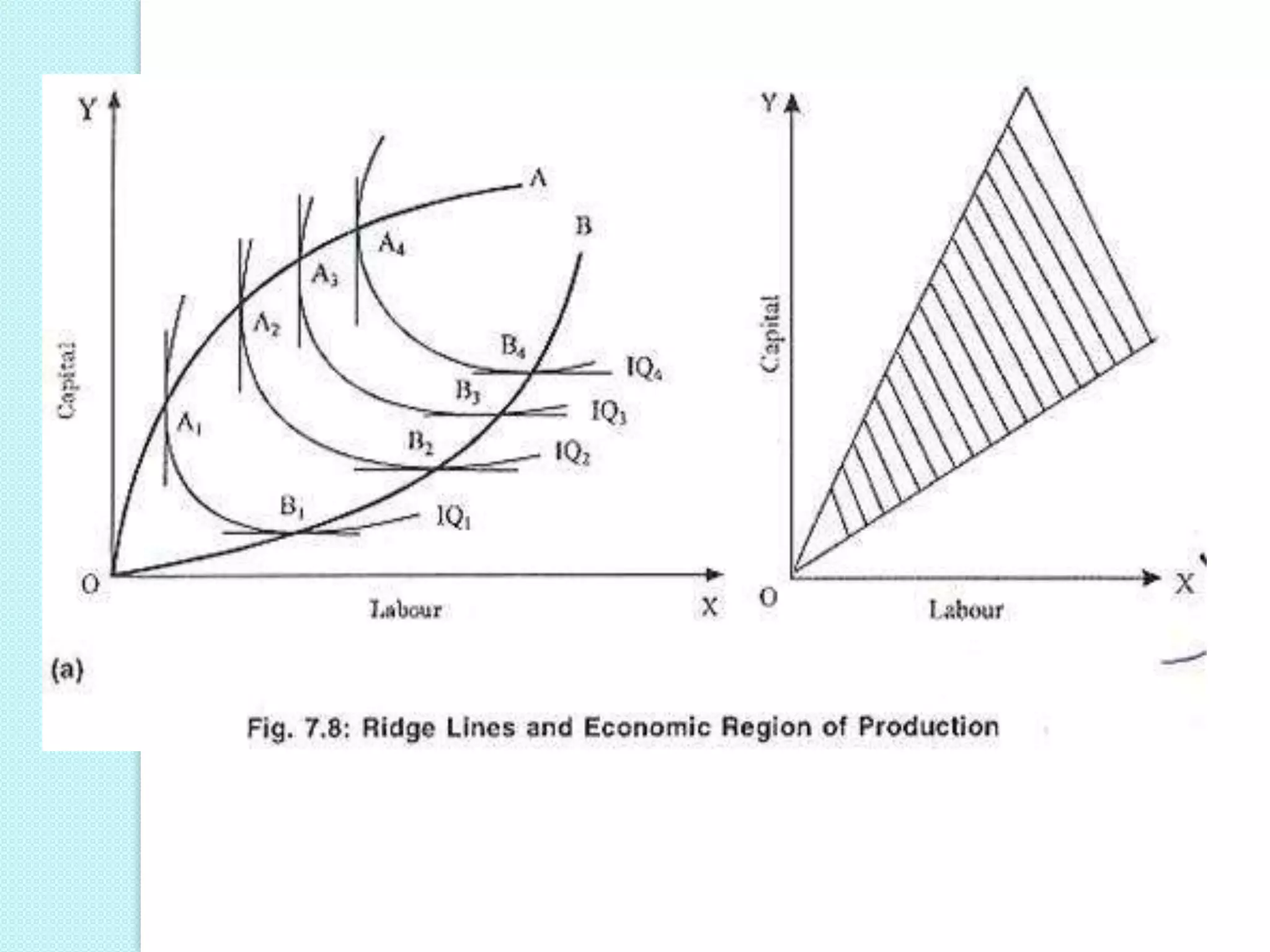

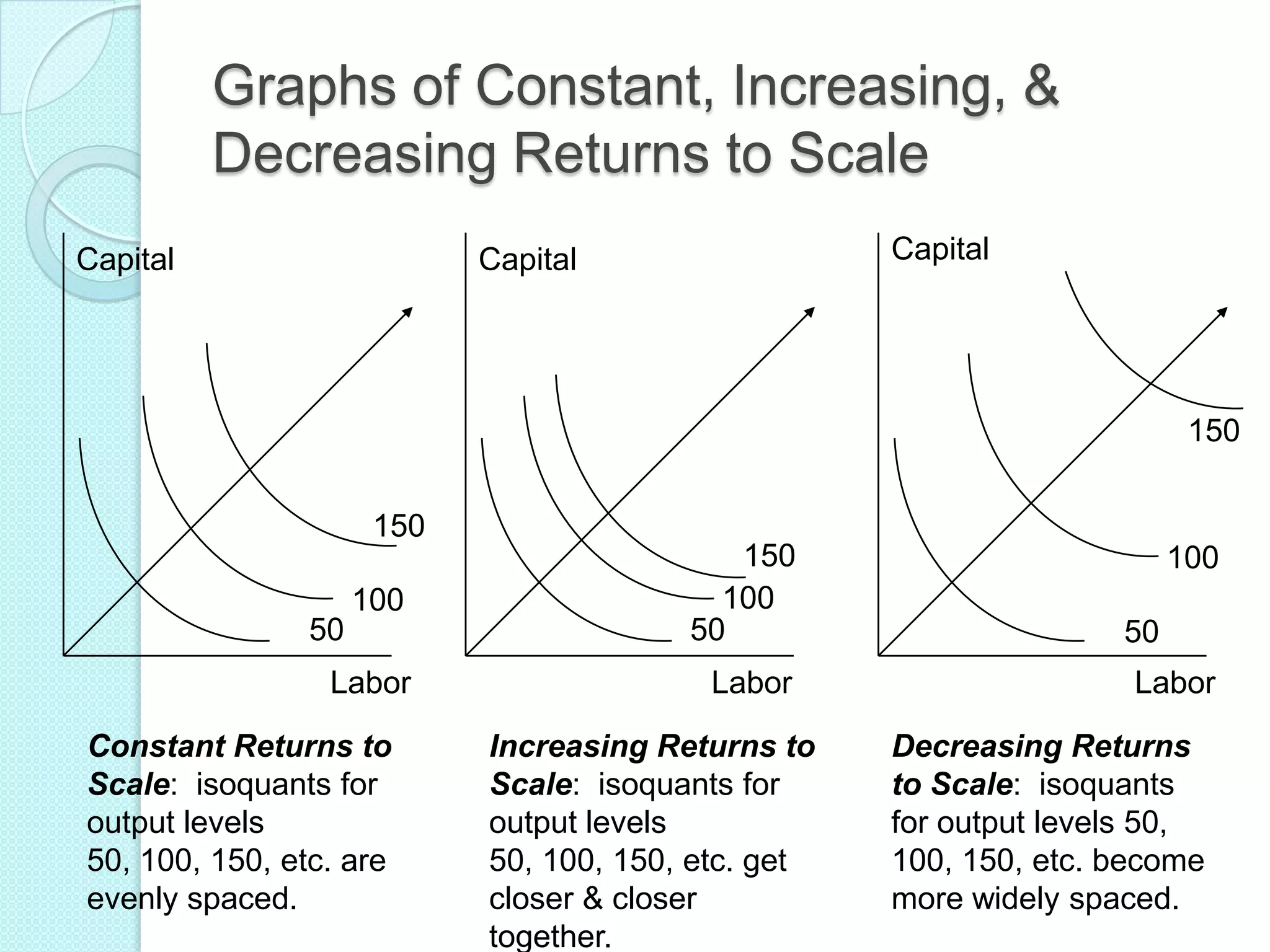

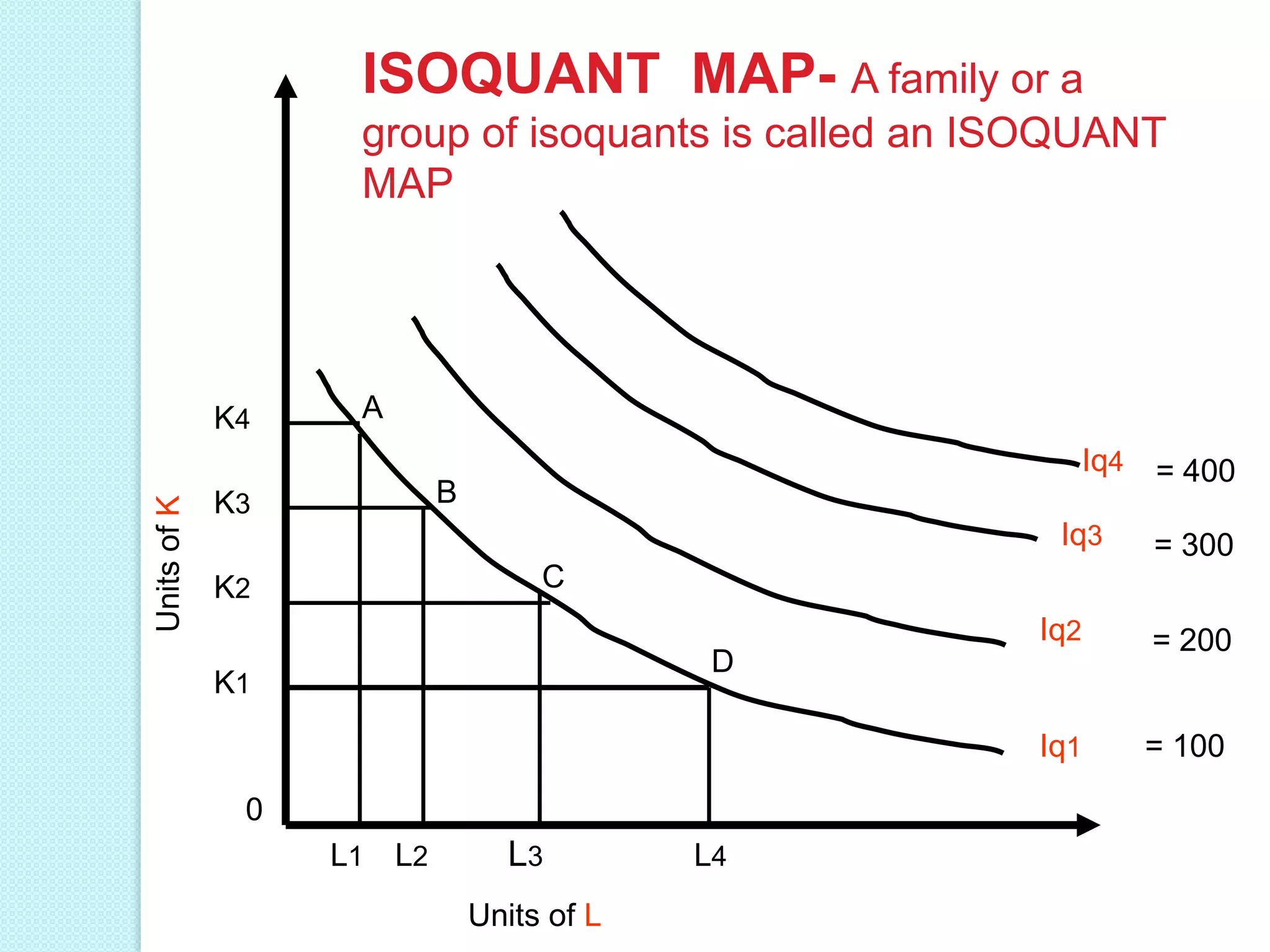

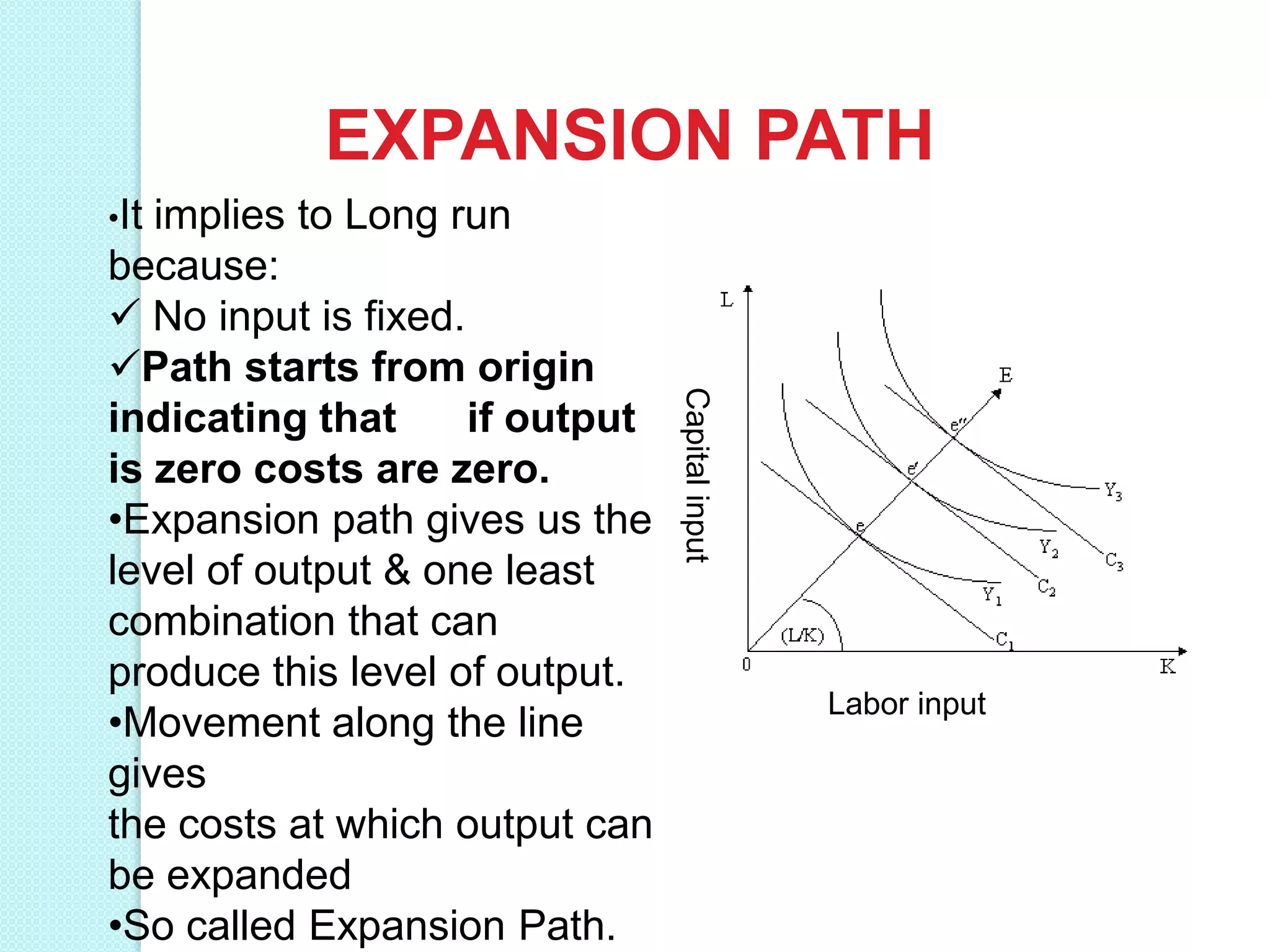

- Long run production functions which consider all inputs as variable. Returns to scale can be increasing, constant, or diminishing based on how total output responds to a proportional increase