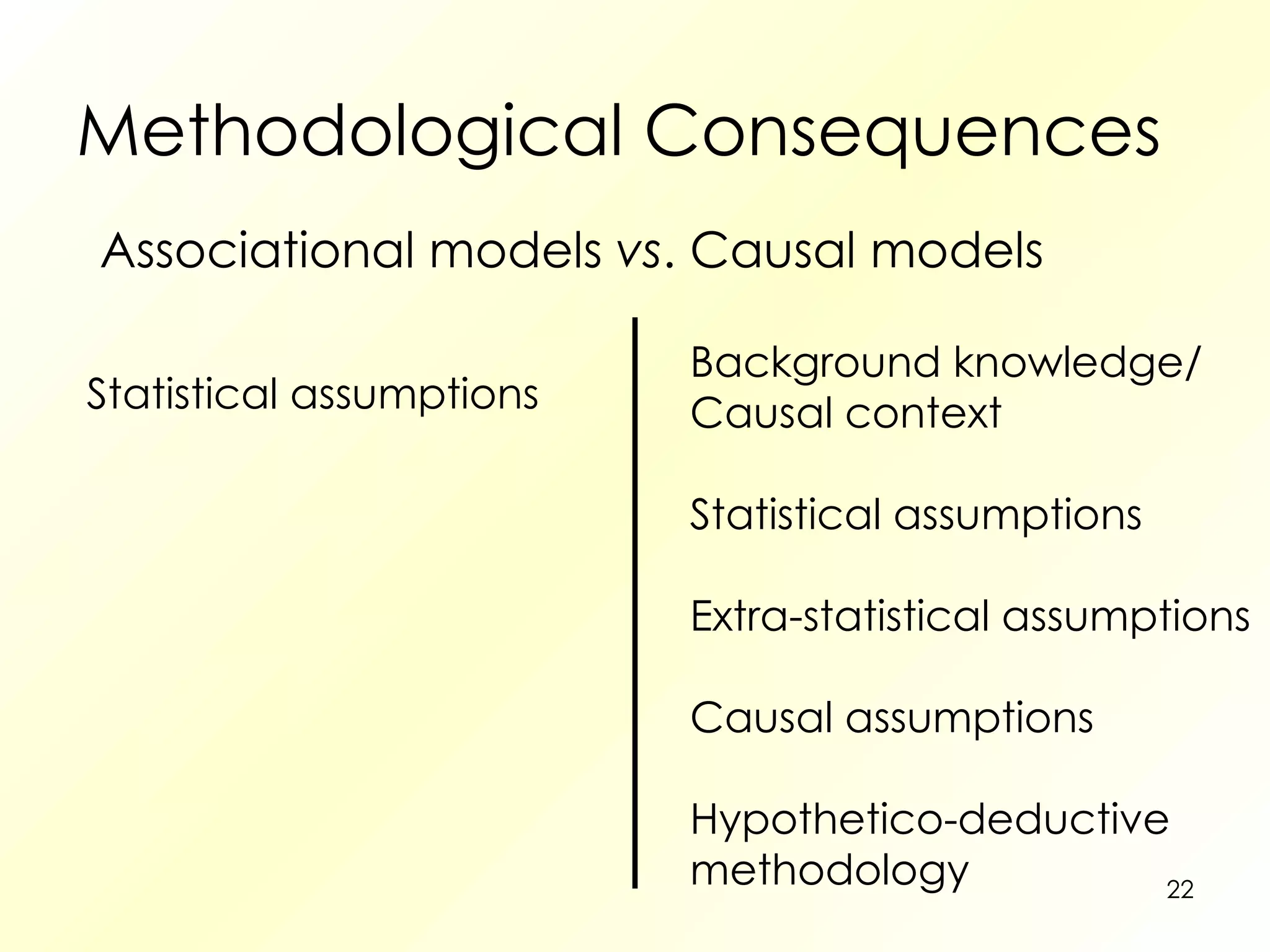

This document discusses the rationale of causality in causal modeling, specifically focusing on the notion of measuring variations. It argues that measuring variations is the principle that guides causal reasoning in causal modeling based on empirical, methodological and philosophical arguments. The rationale of causality in causal modeling centers around identifying and interpreting variations in variables, which is supported by foundational thinkers like Mill, Durkheim, and Quetelet who employed comparative and concomitant variation methods. Objections regarding regularity and invariance are addressed, and methodological consequences for different types of variations are explored.

![Measuring variations Empirical arguments Mother’s Education and Child Survival Caldwell’s causal reasoning: “ If any one of these environmental influences had wholly explained child mortality, and if female education had been merely a proxy for them, the CM [child mortality] index would not have varied with maternal education in that line of the table. This is clearly far from being the case.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pittlunchtimesemjan09-091105094213-phpapp02/75/Pitt-Lunchtime-Sem-Jan09-11-2048.jpg)