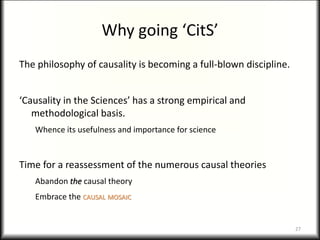

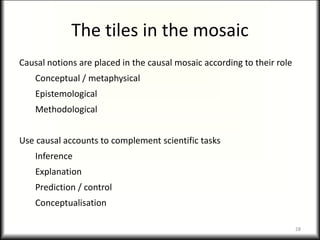

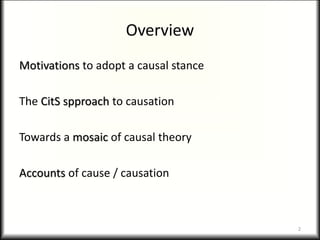

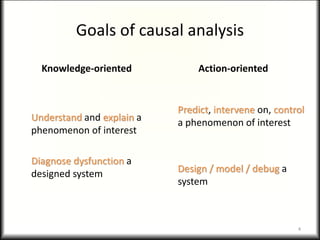

Causality in the Sciences: a gentle introduction discusses adopting a causal approach in science. It argues that causal analysis has knowledge and action oriented goals like understanding phenomena, predicting outcomes, and designing systems. The CitS (Causality in the Sciences) approach analyzes scientific practice to develop philosophical theories grounded in real world problems. It advocates a "causal mosaic" integrating multiple causal concepts like difference-making, mechanisms, capacities and regularities to match diverse scientific tasks. The document concludes causal notions should complement rather than replace scientific work, with resources like conferences and books further developing the CitS approach.

![Do causes need to be causes?

Consider:

Smoking and cancer are associated. Should I quit smoking?

Smoking causes cancer. Should I quit smoking?

Causes trigger actions. Mere beliefs can’t, nor mere associations.

[What about risk factors, then? A debated issue in medical research.]

6

Source: http://xkcd.com/552/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/russoparis-210226161905/85/Causality-in-the-sciences-a-gentle-introduction-6-320.jpg)

![Examples of CitS theses

[Medicine]

Causal assessment has two evidential components:

mechanisms and difference-making

[Social Science]

‘Variation’ guides causal reasoning in model building and model testing

[Biology, Neuroscience]

Mechanisms are entities and activities organised in such a way that

they are responsible for a phenomenon

[Evidence-based approaches]

Evidence hierarchies should not neglect evidence of

mechanisms and expert knowledge

…

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/russoparis-210226161905/85/Causality-in-the-sciences-a-gentle-introduction-10-320.jpg)

![Necessary and sufficient components

Example:

Short circuit caused house fire. Not on its own, but in conjunction with other

factors and in a given background. It is however not redundant because the

other parts are not sufficient to cause fire. The whole thing is itself not

necessary. [Analogous: gene knockout experiments]

Core ideas

Causes are, at minimum, INUS conditions:

“Insufficient but Non-redundant part of a condition

which is itself Unnecessary but Sufficient”

Most famously: J.L. Mackie. In epidemiology: Rothman’s pie charts.

Helps with, e.g.:

Conceptualisation of complex causal settings (disease, concurrent systems, …)

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/russoparis-210226161905/85/Causality-in-the-sciences-a-gentle-introduction-22-320.jpg)