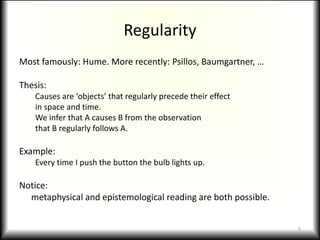

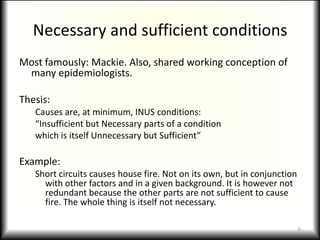

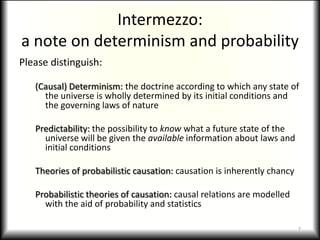

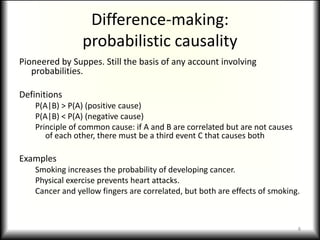

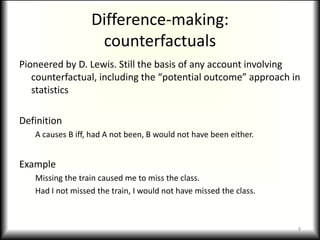

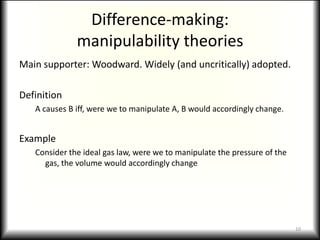

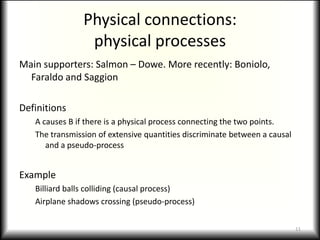

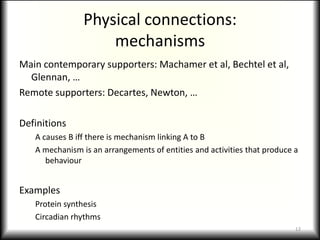

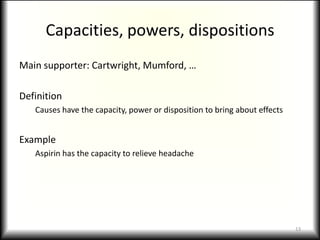

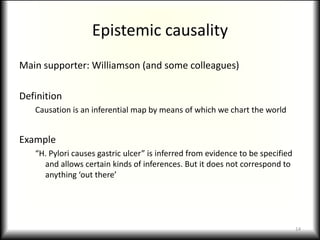

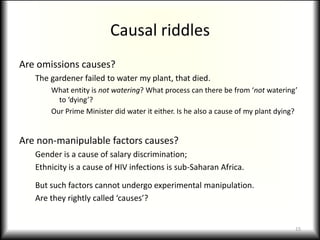

This document discusses different concepts of causation that are debated in philosophy, including regularity, necessary and sufficient conditions, difference-making, physical connections, and capacities/powers. It also discusses different approaches to analyzing causation, such as analyzing folk intuitions, scientific practice, or causal language. Finally, it questions what motivates adopting a causal approach and analyzing causes, such as for understanding, explaining, predicting, intervening, and controlling. The document does not take a stance but aims to present leading concepts and approaches in the current debate on causation.